User:Cdjp1/sandbox/apartheid southern africa

National Forests Office (France)[edit]

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corps_des_chasseurs_forestiers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chasseur#Chasseurs_Forestiers

http://forum.uniforminsignia.org/download/file.php?id=2225&mode=view

TO CREATE/expand[edit]

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C3%B4le_judiciaire_de_la_Gendarmerie_nationale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direction_g%C3%A9n%C3%A9rale_de_la_Gendarmerie_nationale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inspection_g%C3%A9n%C3%A9rale_de_la_Gendarmerie_nationale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie_d%C3%A9partementale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centre_de_planification_et_de_gestion_de_crise https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie_de_l%27Armement https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie_de_la_s%C3%A9curit%C3%A9_des_armements_nucl%C3%A9aires https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie_des_transports_a%C3%A9riens https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peloton_sp%C3%A9cialis%C3%A9_de_protection_de_la_Gendarmerie https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escadron_d%C3%A9partemental_de_s%C3%A9curit%C3%A9_routi%C3%A8re https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Officier_de_police_judiciaire https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Section_de_recherches_(Gendarmerie_nationale) https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brigade_de_recherches https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brigade_d%C3%A9partementale_de_renseignements_et_d%27investigations_judiciaires https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peloton_de_surveillance_et_d%27intervention_de_la_Gendarmerie https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarmerie_pr%C3%A9v%C3%B4tale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commandement_de_la_gendarmerie_outre-mer https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commandement_des_%C3%A9coles_de_la_Gendarmerie_nationale https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gendarme_adjoint_volontaire https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forces_a%C3%A9riennes_de_la_Gendarmerie_nationale

Bourgeois revolution[edit]

sources[edit]

- The Bourgeois Revolution

- 4 - The bourgeois revolution of 1848–9 in Central Europe

- Conceptualizing Bourgeois Revolution: The Prewar Japanese Left and the Meiji Restoration

- Theses on the Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany, 1476-1535

- A Rhetoric of Bourgeois Revolution

- II Economy and Society: A Silent Bourgeois Revolution

- II German Historians and the Problem of Bourgeois Revolution Get access Arrow

- CHINA: THE BOURGEOIS REVOLUTION HAS BEEN ACCOMPLISHED, THE PROLETARIAN REVOLUTION REMAINS TO BE MADE

- Bourgeois Revolution, State Formation and the Absence of the International

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

- [ ]

Intro[edit]

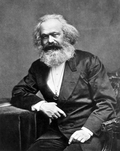

Bourgeois revolution is a term used in Marxist theory to refer to a social revolution that aims to destroy a feudal system or its vestiges, establish the rule of the bourgeoisie, and create a bourgeois (capitalist) state.[1][2] In colonised or subjugated countries, bourgeois revolutions often take the form of a war of national independence. The Dutch, English, American, and French revolutions are considered the archetypal bourgeois revolutions,[3][4] in that they attempted to clear away the remnants of the medieval feudal system, so as to pave the way for the rise of capitalism.[1] The term is usually used in contrast to "proletarian revolution", and is also sometimes called a "bourgeois-democratic revolution".[5][6]

Theories of bourgeois revolution[edit]

According to one version of the two-stage theory, bourgeois revolution was asserted to be a necessary step in the move toward socialism, as codified by Georgi Plekhanov.[7][8] In this view, countries that had preserved their feudal structure, like Russia, would have to establish capitalism via a bourgeois revolution before being able to wage a proletarian revolution.[9][10] At the time of the Russian Revolution, the Mensheviks asserted this theory, arguing that a revolution led by bourgeoisie was necessary to modernise society, establish basic freedoms, and overcome feudalism, which would establish the conditions necessary for socialism.[9] This view is prominent in Marxist-Leninist analysis.[11][12]

Political sociologist Barrington Moore Jr. identified bourgeois revolution as one of three routes from pre-industrial society to the modern world, in which a capitalist mode of production is combined with liberal democracy. Moore identified the English, French, and American revolutions as examples of this route.[13]

Neil Davidson believes that neither the establishment of democracy or the end of feudal relations are defining characteristics of bourgeois revolutions, but instead supports Alex Callinicos' definition of bourgeois revolution as being those that establish "an independent center of capital accumulation".[6][14][15] Charles Post labels this analysis as consequentialism, where there is no requirement of the prior development of capitalism or bourgeois class agency for bourgeois revolutions, and that they are only defined by the effects of the revolutions to promote the development of capital accumulation.[16]

Other theories describe the evolution of the bourgeoisie as not needing a revolution.[17] The German bourgeoisie during the 1848 revolution did not strive to take command of the political effort and instead sided with the crown.[18][19] Davidson attributes their behaviour to the late development of capitalist relations and uses this as the model for the evolution of the bourgeoisie.[20]

Left communists often view the revolutions leading to communist states in the twentieth century as "bourgeois revolutions".[21][22]

The goals of the bourgeois revolution[edit]

According to the Marxist view, the tasks of the bourgeois revolution include:

- The creation of the nation state (which can be constituted differently in different peoples).[23][24]

- The constitution of the state on the basis of popular sovereignty (the rule of law is based on a constitution[25] adopted by the people).

- Bourgeois rule[26] if possible in the form of a democratic republic[27][28] (which, however, already found its complement in tyranny in antiquity).[29]

- The abolition of serfdom, and the formation of free wage workers instead.[30][31]

- The separation of producers from the means of production in primitive accumulation.[32]

- The abolition of the guilds and freedom of investment.[30]

- The free development of the productive forces until they are ripe for social revolution.

Bourgeois revolutions in history[edit]

Bourgeois revolutions in the middle ages[edit]

Although with much less diffusion, some social movements of the European Late Middle Ages have also received the name of bourgeois revolution, in which the bourgeoisie begins to define itself in the nascent cities as a social class. Examples include the Ciompi Revolt in the Republic of Florence, Jacquerie revolts during the Hundred Years' War in France,[33] and Bourgeois revolts of Sahagún in Spain.[34][35]

Bourgeois revolutions in the early modern period[edit]

The first wave of bourgeois revolutions are those that occurred within the early modern period and were typically marked by being driven from below by the petty bourgeoisie against absolutist governments.[6]

German Peasants' War (1524–1525) (it has been labelled by later historians as an early attempt at a bourgeois revolution)[36]

German Peasants' War (1524–1525) (it has been labelled by later historians as an early attempt at a bourgeois revolution)[36] Eighty Years' War, also known as the Dutch revolution, (1566–1648)[3][37]

Eighty Years' War, also known as the Dutch revolution, (1566–1648)[3][37] English Revolution (1640–1660)[3][4][6]

English Revolution (1640–1660)[3][4][6] American Revolution (1765–1783)[3][6]

American Revolution (1765–1783)[3][6] French Revolution (1789–1799)[38][3]

French Revolution (1789–1799)[38][3] Irish Rebellion of 1798[39]

Irish Rebellion of 1798[39]

Bourgeois revolutions in the late modern period[edit]

The second wave of bourgeois revolutions are those that occurred within the late modern period and were typically marked by being led from above by the haute bourgeoisie.[6]

July Revolution (1830)[40]

July Revolution (1830)[40] February Revolution (1848)[41][42]

February Revolution (1848)[41][42] German revolutions of 1848–1849[43]

German revolutions of 1848–1849[43]Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states[44][42]

Hungarian Revolution of 1848[44][45]

Hungarian Revolution of 1848[44][45] Risorgimento (1848–1871)[46]

Risorgimento (1848–1871)[46] Unification of Germany (1866–1871)[46]

Unification of Germany (1866–1871)[46] American Civil War (1861–1865)[47]

American Civil War (1861–1865)[47] Japanese Revolution (1868–1869)[48][46]

Japanese Revolution (1868–1869)[48][46] Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)[49]

Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)[49] 1905 Russian Revolution (1905–1907)[50][6]

1905 Russian Revolution (1905–1907)[50][6] Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911)[51]

Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911)[51] Young Turk Revolution (1908)[52]

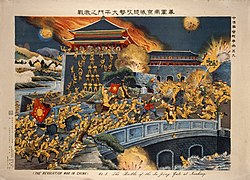

Young Turk Revolution (1908)[52] Chinese revolution of 1911 (1911–1912)[53][6]

Chinese revolution of 1911 (1911–1912)[53][6] Mexican Revolution (1910–1917)[54]

Mexican Revolution (1910–1917)[54] February Revolution (1917) (called a "bourgeois-democratic revolution" in Soviet historiography)[55][56]

February Revolution (1917) (called a "bourgeois-democratic revolution" in Soviet historiography)[55][56] /

/ Chinese revolution (1925–1953)[57][21]

Chinese revolution (1925–1953)[57][21]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Bourgeois Revolution". TheFreeDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Walker & Gray (2014), p. 118; Calvert (1990), pp. 9–10; Hobsbawm (1989), pp. 11–12 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFHobsbawm1989 (help)

- ^ a b c d e Eisenstein (2010), p. 64 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEisenstein2010 (help), quoted in Davidson, Neil (2012). "From Society to Politics; From Event to Process". How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. pp. 381–382. ISBN 978-1-60846-067-0.

- ^ a b Callinicos 1989, pp. 113–171. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCallinicos1989 (help)

- ^ Wilczynski, Jozef, ed. (1981). "Bourgeois Revolution". An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Marxism, Socialism and Communism. London: Macmillan Press. p. 48. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-05806-8. ISBN 978-1-349-05806-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davidson, Neil (May 2012). "Bourgeois Revolution and the US Civil War". International Socialist Review. No. 83. Center For Economic Research and Social Change. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021.

- ^ Post 2019, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Plekhanov, Georgi (1949) [1895]. The Bourgeois Revolution: The Political Birth of Capitalism. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "Stagism". Encyclopedia of Marxism. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Lane, David (22 April 2020). "Revisiting Lenin's theory of socialist revolution on the 150th anniversary of his birth". European Politics and Policy. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020.

- ^ Caputo, Renato. "Grandezza e limiti della rivoluzione borghese in Marx" [Magnitude and limits of the bourgeois revolution in Marx]. La Città Futura (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Cervelli, Innocenzo (1976). "Sul concetto di rivoluzione borghese" [On the concept of bourgeois revolution]. Studi Storici (in Italian). 17 (1): 147–155. JSTOR 20564411. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Calvert 1990, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Gluckstein, Donny (7 October 2013). "Comment on bourgeois revolutions". International Socialism (140). Archived from the original on 18 May 2017.

- ^ Post 2019, pp. 160–161, 166–167.

- ^ Post 2019, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Blackbourn, David. Economy and Society: A Silent Bourgeois Revolution. pp. 176–205. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. in Blackbourn & Eley (1984)

- ^ Hallas (1988), pp. 17–20; Klíma (1986), pp. 93–94; Calvert (1990), pp. 53–55

- ^ Blackbourn, David. Economy and Society: The shadow side. pp. 206–237. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. in Blackbourn & Eley (1984)

- ^ Davidson, Neil (2012). "Marx and Engels (2) 1847–52". How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-60846-067-0.

In a world where most states have not yet experienced bourgeois revolutions, where most are even more economically underdeveloped than Germany, they too will give rise to "belated" bourgeoisies, the implication being that it is Germany rather than France that represents the likely pattern of bourgeois development.

- ^ a b "China: The bourgeois Revolution has been accomplished, the proletarian Revolution remains to be made". Communist Program (3). May 1977. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023 – via International Library of the Communist Left.

- ^ Post 2019, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 8, p. 197.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 16, p. 157.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 37, p. 463.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 8, p. 196.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 22, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Elsenhans, Hartmut (2012). "Democratic revolution, bourgeois revolution, Arab revolution: The political economy of a possible success". NAQD. 29 (1): 51–60. doi:10.3917/naqd.029.0051. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 17, p. 337.

- ^ a b Marx & Engels 1956, 17, p. 592.

- ^ Heller 2006, Introduction pp. 2–4.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1956, 23, pp. 741–761.

- ^ Mollat, Michel [in French]; Wolff, Philippe [in French] (1970). Ongles bleus, jacques et ciompi - les révolutions populaires en Europe aux XIVe et XVe siècles [Ongles bleus, Jacquerie and Ciompi - popular revolutions in Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries] (in French). Calmann-Lévy.

- ^ Pastor de Togneri, Reyna [in Spanish] (1973). Conflictos sociales y estancamiento económico en la España medieval [Social conflicts and economic stagnation in medieval Spain] (in Spanish). Editorial Ariel.

- ^ Martín, José Luis. Historia de España [History of Spain (A society at war)]. Historia 16 (in Spanish). Vol. 4 - Una sociedad en guerra.

- ^ Bak, Janos (2022) [1976]. "'The Peasant War in Germany' by Friedrich Engels – 125 years later". In Bak, Janos (ed.). The German Peasant War of 1525. Routledge. pp. 93–99. doi:10.4324/9781003190950. ISBN 978-1-00-319095-0. S2CID 241881702.

- ^ Hallas 1988, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Heller (2006), Preface p. ix; Callinicos (1989), pp. 113–171 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCallinicos1989 (help); Sewell (1994), Introduction pp. 22–23

- ^ Faulkner, Neil (24 October 2011). "A Marxist History of the World part 49: The French Revolution – Themidor, Directory and Napoleon". Counterfire. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973a, p. 172.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973a, p. 233.

- ^ a b Klíma 1986, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group (1973a), p. 255; Callinicos (1989), pp. 113–171 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCallinicos1989 (help); Hallas (1988), pp. 17–20; Klíma (1986), pp. 74–75

- ^ a b Modern World History Writing Group 1973a.

- ^ Klíma 1986, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Post 2019, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Faulkner, Neil (8 January 2012). "A Marxist History of the World part 57: The American Civil War". Counterfire. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023.

- ^ Faulkner, Neil (18 January 2012). "A Marxist History of the World part 58: The Meiji Restoration". Counterfire. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973b, p. 150.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973b, p. 130.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973b, p. 152.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973b, p. 160.

- ^ Zhang, Yuchun; Ma, Zhenwen (1976). 简明中国近代史 [A Concise Modern History of China] (in Chinese). Liaoning People's Publishing House. p. 301.

- ^ Modern World History Writing Group 1973b, p. 224.

- ^ Commission of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b), ed. (1938). "Istoriya Vsesoyuznoy kommunisticheskoy partii (bol'shevikov). Kratkiy kurs" История Всесоюзной коммунистической партии (большевиков). Краткий курс [History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Short course] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 April 2023.

- ^ Genkina, Esfir Borisovna [in Russian] (1927). Pokrovsky, Mikhail Nikolaevich [in Russian] (ed.). Fevral'skiy perevorot // Ocherki po istorii Oktyabr'skoy revolyutsii Февральский переворот // Очерки по истории Октябрьской революции [The February coup // Essays on the history of the October Revolution] (in Russian). Vol. 2.

- ^ Post 2019, pp. 160–163.

Bibliography[edit]

- Blackbourn, David; Eley, Geoff, eds. (12 December 1984). The Peculiarities of German History: Bourgeois Society and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Germany. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198730583.001.0001. ISBN 9780191694943. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023.

- Callinicos, Alex (Summer 1989). "Bourgeois Revolutions and Historical Materialism". International Socialism. 2 (43): 113–171. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Calvert, Peter (1990). Revolution and Counter-Revolution. Concepts in the Social Sciences. Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15397-6.

- Eisenstein, Hester (13 May 2010). Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women's Labor and Ideas to Exploit the World. Routledge. ISBN 9781594516603.

- Hallas, Duncan (January 1988). "The Bourgeois Revolution". Socialist Review. No. 105. Socialist Workers Party. pp. 17–20. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Heller, Henry (2006). The Bourgeois Revolution in France 1789–1815. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-650-4. JSTOR j.ctt9qdczd.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (Spring 1989). "The Making of a "Bourgeois Revolution"". Social Research. 56 (1). The New School: 5–31. JSTOR 40970532.

- Johnson, Elliott; Walker, David; Gray, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Democracy". Historical Dictionary of Marxism (2nd ed.). Lanham; Boulder; New York; London: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4422-3798-8.

- Klíma, Arnošt (1986). "4 - The bourgeois revolution of 1848–9 in Central Europe". In Porter, Roy; Teich, Mikuláš (eds.). Revolution in History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–100. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316256961. ISBN 9781316256961.

- Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1956). Marx-Engels-Werke. Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin.

- Modern World History Writing Group (June 1973a). Shanghai Normal University (ed.). 世界近代史 [Book of Modern World History] (in Chinese). Vol. I. Shanghai People's Press.

- Modern World History Writing Group (June 1973b). Shanghai Normal University (ed.). 世界近代史 [Book of Modern World History] (in Chinese). Vol. II. Shanghai People's Press.

- Post, Charles (2019). "How Capitalist Were the 'Bourgeois Revolutions'?". Historical Materialism. 27 (3). Brill: 157–190. doi:10.1163/1569206X-12341528. S2CID 149303334. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023.

- Sewell, William H. (December 1994). A Rhetoric of Bourgeois Revolution: The Abbe Sieyes and What is the Third Estate?. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822315384.

Proletarian revolution[edit]

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system.[1][2] Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, communists and anarchists.

Interpretations[edit]

The concept of a revolutionary proletariat was first put forward by the French revolutionary socialist and radical Auguste Blanqui.[3] The Paris Commune, contemporary to Blanqui and Marx, being viewed by some as the first attempt at a proletarian revolution.[4]

Marxists believe proletarian revolutions can and will likely happen in all capitalist countries,[5][6] related to the concept of world revolution. The objective of a proletarian revolution, according to Marxists, is to transform the bourgeois state into a workers' state.[7] The traditional Marxist belief was that a proletarian revolution could only occur in a country where capitalism had developed.[8][9]

The Leninist branch of Marxism argues that a proletarian revolution must be led by a vanguard of "professional revolutionaries", men and women who are fully dedicated to the communist cause and who form the nucleus of the communist revolutionary movement. This vanguard is meant to provide leadership and organization to the working class before and during the revolution, which aims to prevent the government from successfully ending it.[10] Vladimir Lenin believed that it was imperative to arm the working class to secure their leverage over the bourgeoisie. Lenin's words were printed in an article in German on the nature of pacifism and said "In every class society, whether based on slavery, serfdom, or, as at present, on wage-labour, the oppressor class is always armed."[11] It was under such conditions that the first successful proletarian revolution, the Russian revolution, occurred.[12][11][13]

Other Marxists, such as Luxemburgists, disagree with the Leninist idea of a vanguard and insist that the entire working class—or at least a large part of it—must be deeply involved and equally committed to the socialist or communist cause for a proletarian revolution to be successful.[14] To this end, they seek to build mass working class movements with a very large membership.[citation needed]

Finally, there are socialist anarchists and libertarian socialists. Their view is that the revolution must be a bottom-up social revolution which seeks to transform all aspects of society and the individuals which make up the society (see Asturian Revolution and Revolutionary Catalonia). Alexander Berkman said "there are revolutions and revolutions. Some revolutions change only the governmental form by putting a new set of rulers in place of the old. These are political revolutions, and as such they often meet with little resistance. But a revolution that aims to abolish the entire system of wage slavery must also do away with the power of one class to oppress another. That is, it is not any more a mere change of rulers, of government, not a political revolution, but one that seeks to alter the whole character of society. That would be a social revolution."[15]

See also[edit]

- Communist revolution

- Free association of producers, the ultimate goal of communist and anarchist revolutions

- Labour revolt

- October Revolution

- Asturian miners' strike of 1934

- Revolution of 1934

- Proletarian Revolutionary Organisation, Nepal

- Social revolution

- World revolution

References[edit]

- ^ Liulevicius, Vejas (13 July 2020). "Russia: The Unlikely Place for a Proletarian Revolution". The Great Courses Daily. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir (1918). "Chapter I: Class Society and the State". The State and Revolution – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Blake, William James (1939). An American Looks at Karl Marx. Cordon Company. p. 622 – via Google Books.

- ^ Spector, Maurice (15 March 1934). "The Paris Commune and the Proletarian Revolution". The Militant. Vol. III, no. 11. p. 3 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Blackburn, Robin (May–June 1976). "Marxism: Theory of Proletarian Revolution". New Left Review. I (97).

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (October–November 1847). The Principles of Communism – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Further, it has co-ordinated the social development of the civilized countries to such an extent that, in all of them, bourgeoisie and proletariat have become the decisive classes, and the struggle between them the great struggle of the day. It follows that the communist revolution will not merely be a national phenomenon but must take place simultaneously in all civilized countries – that is to say, at least in England, America, France, and Germany.

- ^ Goichbarg, Alexander [in German]. Revolução Proletária e Direito Civil [Proletarian Revolution and Civil Law] (in Portuguese).

- ^ Lane, David (22 April 2020). "Revisiting Lenin's theory of socialist revolution on the 150th anniversary of his birth". European Politics and Policy. London School of Economics.

- ^ Filho, Almir Cezar. "Moreno e os 80 anos do debate sobre a Revolução Permanente" [Moreno and the 80 years of the debate on the Permanent Revolution] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir (1918). The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky.

- ^ a b Dunayevskaya, Raya (5 June 2017). "Lenin on Self-determination of Nations and on Organization After His Philosophic Notebooks". In Gogol, Eugene; Dmitryev, Franklin (eds.). Russia: From Proletarian Revolution to State-Capitalist Counter-Revolution. Brill. pp. 125–141. doi:10.1163/9789004347618_005. ISBN 978-90-04-34761-8. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (May–June 1967). "The Unfinished Revolution: 1917–67" (PDF). New Left Review. I (43).

- ^ Chácon, Justin Akers (2018). "Introduction". Radicals in the Barrio: Magonistas, Socialists, Wobblies, and Communists in the Mexican American Working Class. Chicago, IL.: Haymarket Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-60846-776-1.

- ^ Várnagy, Tomás (19 April 2021). "A Central European Revolutionary: Rosa Luxemburg's remarkable, revolutionary life for democracy and socialism". Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ Berkman, Alexander (1929). "25". .

English Revolution[edit]

The English Revolution is a term that describes two separate events in English history. Prior to the 20th century, it was generally applied to the 1688 Glorious Revolution, when James II was deposed and a constitutional monarchy established under William III and Mary II.[1][2]

However, Marxist historians began using it for the period covering the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms and the Interregnum that followed the Execution of Charles I in 1649, before the 1660 Stuart Restoration had returned Charles II to the throne.[3] Writing in 1892, Friedrich Engels described this period as "the Great Rebellion" and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as "comparatively puny", although he claimed that both were part of the same revolutionary movement.[4] Later historians have also used this definition of the English Revolution in their work.[5]

Although Charles II was retroactively declared to have been the legal and rightful monarch since the death of his father in 1649,[6][7] which resulted in a return to the status quo in many areas, a number of gains made under the Commonwealth remained in law.[8][9]

Whig theory[edit]

Tensions regarding the English monarchy began well before the Glorious Revolution. When Charles I was executed in 1649 by the English Parliament, England entered into a republic, or Commonwealth, that lasted until Charles II was reestablished as king of England in 1660. The intermittent civil wars that lasted between 1649 and 1688 were a "constitutional struggle originating from the unresolved contradictions fostered by the Reformation."[10][11] Debates amongst the England’s post-Reformation state and the constitutional basis for civil involvement in ecclesiastical and governmental issues continually converged together.[10] During the Glorious Revolution of 1688, King James II was replaced by the monarchs William III and Mary II, and a constitutional monarchy was established that was described by Whig historians as the "English Revolution".[1][12][11] That interpretation suggests that the "English Revolution" was the final act in the long process of reform and consolidation by Parliament to achieve a balanced constitutional monarchy in Britain, with laws made that pointed towards freedom.[13][11]

Marxist theory[edit]

The Marxist view of the English Revolution, suggests that the events of 1640 to 1660 in Britain were a bourgeois revolution[14] in which the final section of English feudalism (the state) was destroyed by a bourgeois class (and its supporters) and replaced with a state (and society), which reflected the wider establishment of agrarian (and later industrial) capitalism. Such an analysis sees the English Revolution as pivotal in the transition from feudalism to capitalism and from a feudal state to a capitalist state in Britain.[15][16]

The phrase "English Revolution" was first used by Marx in the short text "England's 17th Century Revolution", a response to a pamphlet on the Glorious Revolution of 1688 by François Guizot.[17] Oliver Cromwell and the English Civil War are also referred to multiple times in the work The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, but the event is not directly referred to by the name.[18] By 1892, Engels was using the term "The Great Rebellion" for the conflict, and, while still recognising it as part of the same revolutionary event, dismissed the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as "comparatively puny".[4]

According to the Marxist historian Christopher Hill:

The Civil War was a class war, in which the despotism of Charles I was defended by the reactionary forces of the established Church and conservative landlords, and on the other side stood the trading and industrial classes in town and countryside ... the yeomen and progressive gentry, and ... wider masses of the population whenever they were able by free discussion to understand what the struggle was really about.[19]

Later developments of the Marxist view moved on from the theory of bourgeois revolution to suggest that the English Revolution anticipated the French Revolution and later revolutions in the field of popular administrative and economic gains.[citation needed] Along with the expansion of parliamentary power, the English Revolution broke down many of the old power relations in both rural and urban English society.[19][20] The guild democracy movement of the period won its greatest successes among London's transport workers, most notably the Thames Watermen, who democratized their company in 1641–43.[21] With the outbreak of civil war in 1642, rural communities began to seize timber and other resources on the estates of royalists, Catholics, the royal family and the church hierarchy. Some communities improved their conditions of tenure on such estates.[citation needed]

The old status quo began a retrenchment after the end of the main civil war in 1646, and more especially after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, but some gains endured in the long term. The democratic element introduced in the watermen's company in 1642, for example, survived, with vicissitudes, until 1827.[8][9]

The Marxist view also developed a concept of a “Revolution within the Revolution” (pursued by Hill, Brian Manning and others), which placed a greater deal of emphasis on the radical movements of the period (such as the agitator Levellers, mutineers in the New Model Army and the Diggers), who attempted to go further than Parliament in the aftermath of the Civil War.

There were, we may oversimplify, two revolutions in mid-seventeenth-century England. The one which succeeded established the sacred rights of property (abolition of feudal tenures, no arbitrary taxation), gave political power to the propertied (sovereignty of Parliament and common law, abolition of prerogative courts), and removed all impediments to the triumph of the ideology of the men of property – the protestant ethic. There was, however, another revolution that never happened, though from time to time it threatened. This might have established communal property, a far wider democracy in political and legal institutions, might have disestablished the state church, and rejected the Protestant ethic.[22]

Brian Manning claimed:

The old ruling class came back with new ideas and new outlooks which were attuned to economic growth and expansion and facilitated, in the long run, the development of a fully capitalist economy. It would all have been very different if Charles I had not been obliged to summon that Parliament to meet at Westminster on November 3rd, 1640.[23]

Criticism[edit]

The idea, while popular among Marxist historians, has been criticised by many historians of more liberal schools,[24] and of revisionist schools.[25]

The notion that the events of 1640 to 1660 constitute an English Revolution has been criticized by historians such as Austin Woolrych, who pointed out that

painstaking research in the county after county, in local record offices, and family archives, has revealed that the changes in the ownership of the real estate, and hence in the composition of the governing class, were nothing like as great as used to be thought.[26]

Woolrych argues that the notion that the period constitutes an "English Revolution" not only ignores the lack of significant social change contained within the period but also ignores the long-term trends of the early modern period which extend beyond this narrow time frame.

Neither Karl Marx nor Friedrich Engels ever ignored the further development of the bourgeois state beyond that point, however, as is clear from their writings on the Industrial Revolution.[27]

Other uses[edit]

The term "English Revolution" is also used by non-Marxists in the Victorian period to refer to 1642 such as the critic and writer Matthew Arnold in The Function of Criticism at the Present Time: "This is what distinguishes it [the French Revolution] from the English Revolution of Charles the First's time".[28]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Trevelyan 1938, p. ?.

- ^ Hobsbawm, E. J. (Spring 1989). "The Making of a "Bourgeois Revolution"". Social Research. 56 (1). The New School: 5–31. JSTOR 40970532.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1920). "4: Terrorism". Terrorism and Communism – via Marxists Internet Archive.

In the seventeenth century England carried out two revolutions. The first, which brought forth great social upheavals and wars, brought amongst other things the execution of King Charles I, while the second ended happily with the accession of a new dynasty. [...] The reason for this difference in estimates was explained by the French historian, Augustin Thierry. In the first English revolution, in the "Great Rebellion," the active force was the people; while in the second it was almost "silent." [...] But the great event in modern "bourgeois" history is, nonetheless, not the "Glorious Revolution," but the "Great Rebellion."

- ^ a b Engels, Friedrich (1892). "1892 English Edition Introduction". Socialism: Utopian and Scientific – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Bulman, William J. (13 December 2021). "The English Revolution and the History of Majority Rule". Centre for Intellectual History, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023.

- ^ House of Commons 1802a.

- ^ Harris, Tim (2005). Restoration: Charles II and His Kingdoms, 1660–1685. London: Allen Lane. p. 47. ISBN 0-7139-9191-7.

- ^ a b O'Riordan, Christopher (1992). "Self-determination and the London Transport Workers in the Century of Revolution". Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- ^ a b O'Riordan, Christopher (1993). "Popular Exploitation of Enemy Estates in the English Revolution". History. 78 (253): 184–200. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1993.tb01577.x. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- ^ a b Neufeld, Matthew (2015). "From Peacemaking to Peacebuilding: The Multiple Endings of England's Long Civil Wars". The American Historical Review. 120 (5): 1709–1723. doi:10.1093/ahr/120.5.1709. JSTOR 43697072 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c "Great rebellion, English Revolution or War of Religion?". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023.

- ^ Yerby, George (2020). "Introduction: Recovering the Economic Context of History". The Economic Causes of the English Civil War: Freedom of Trade and the English Revolution. Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-429-32555-7.

- ^ Richardson, R. C. (1988) [1977]. "3. The Eighteenth Century: The Political Uses of History". The Debate on the English Revolution. Issues in Historiography (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 36–55. ISBN 0-415-01167-1.

- ^ Eisenstein (2010), p. 64 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEisenstein2010 (help), quoted in Davidson, Neil (2012). "From Society to Politics; From Event to Process". How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. pp. 381–382. ISBN 978-1-60846-067-0.

- ^ Callinicos, Alex (Summer 1989). "Bourgeois Revolutions and Historical Materialism". International Socialism. 2 (43): 113–171 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Davidson, Neil (May 2012). "Bourgeois Revolution and the US Civil War". International Socialist Review. No. 83. Center For Economic Research and Social Change.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1850). "England's 17th Century Revolution: A Review of Francois Guizot's 1850 pamphlet Pourquoi la revolution d'Angleterre a-t-elle reussi?". Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Marx, Karl. "Index". The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Hill, Christopher (2002) [1940]. The English Revolution 1640 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ "Causes of the English Civil War: What caused the civil war? What part did Cromwell play in causing the war?". The Cromwell Association. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Today in London Radical History, 1768: 2000 Thames Watermen Picket Royal Exchange & Mansion House, 1768, Over a Decline in Trade". Pasttense: London Radical Histories. 9 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023.

- ^ Hill, Christopher (1991). The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas in the English Revolution (New ed.). Penguin.

- ^ Manning, Brian (3 March 1984). "What Was the English Revolution". History Today. 34 (3). Archived from the original on 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Great rebellion, English Revolution or War of Religion?". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021.

- ^ Stone, Lawrence (2017) [1972]. "Foreword (by Clare Jackson)". The Causes of the English Revolution 1529–1642 (Routledge Classics ed.). Routledge. pp. xiv–xv. ISBN 978-1-315-18492-0.

- ^ Woolrych, Austin (2002). Britain in Revolution, 1625–1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 794.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich. "Marx and Engels: On the Industrial Revolution: Primitive Accumulation and The Condition of the Working Class". Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Arnold, Matthew. The Function of Criticism at the Present Time (PDF). Blackmask.

Sources[edit]

- Eisenstein, Hester (13 May 2010). Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women's Labor and Ideas to Exploit the World. Routledge. ISBN 9781594516603.

- "House of Commons Journal Volume 8: 8 May 1660". Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 8, 1660–1667. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office: 16–18. 1802a.

- Trevelyan, George M. (1938). The English Revolution, 1688-1689 (1965 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-7240010488.

- The English Civil War Interpreted by Marx and Engels - Christopher Hill

- WHEN WAS THE ENGLISH REVOLUTION? - ANGUS McINNES

- The London Revolution 1640-1643: Class Struggles in 17th Century England

Ecofascism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

|

Death toll: 170 Injury toll: 398

Citations 2, 4, and 9 need to also be referenced in main body.

Ecofascism is a term used to describe individuals and groups which combine environmentalism with fascism.[1]

Philosopher André Gorz characterized eco-fascism as hypothetical forms of totalitarianism based on an ecological orientation of politics.[2] Similar definitions have been used by others in older academic literature in accusations of ecofascism of "environmental fascism".[3] However, since the 2010s, a number of individuals and groups have emerged that either self-identify as "ecofascist" or have been labelled as "ecofascist" by academic or journalistic sources.[4] These individuals and groups synthesise radical far-right politics with environmentalism,[5][6] and will typically argue that overpopulation is the primary threat to the environment and that the only solution is a complete halt to immigration or, at their most extreme, genocide against minority groups and ethnicities.[7] Many far-right political parties have added green politics to their platforms.[8][9][10] Through the 2010s ecofascism has seen increasing support.[11]

Definition[edit]

‘’Need Bookchin’s definition’’

In 2005, environmental historian Michael E. Zimmerman defined "ecofascism" as "a totalitarian government that requires individuals to sacrifice their interests to the well-being of the 'land', understood as the splendid web of life, or the organic whole of nature, including peoples and their states",[1] this was supported by philosopher Patrick Hassan’s work analysing historical accusations of ecofascism in the academic literature.[12] Zimmerman argued that while no ecofascist government has existed so far, "important aspects of it can be found in German National Socialism, one of whose central slogans was "Blood and Soil".[1][13] Other political agendas instead of environmental protection and prevention of climate change are nationalist approaches to climate such as national economic environmentalism, securitization of climate change, and ecobordering.[14]

Ecofascists often believe there is a symbiotic relationship between a nation-group and its homeland.[15] They often blame the global south for ecological problems,[16][17] with their proposed solutions often entailing extreme population control measures based on racial categorisations,[18] and advocating for the accelerated collapse of current society to be replaced by fascist societies.[19] This latter belief is often accompanied with vocal support for terrorist actions.[20][21][22]

Vice has defined ecofascism as an ideology "which blames the demise of the environment on overpopulation, immigration, and over-industrialization, problems that followers think could be partly remedied through the mass murder of refugees in Western countries."[8] Environmentalist author Naomi Klein has suggested that ecofascists' primary objectives are to close borders to immigrants and, on the more extreme end, to embrace the idea of climate change as a divinely-ordained signal to begin a mass purge of sections of the human race. Ecofascism is "environmentalism through genocide", opined Klein.[9] Political researcher Alex Amend defined ecofascist belief as "The devaluing of human life—particularly of populations seen as inferior—in order to protect the environment viewed as essential to White identity."[23]

Terrorism researcher Kristy Campion defined ecofascism as "a reactionary and revolutionary ideology that champions the regeneration of an imagined community through a return to a romanticised, ethnopluralist vision of the natural order."[24]

Helen Cawood and Xany Jansen Van Vuuren have criticised previous attempts to define ecofascism as focusing too heavily on environmental and ecological conservationism in historical fascist movements, and the subsequent definitions being too broad and encompassing many ontologically different ideologies.[25] In their criticism they summarise the current definition of ecofascism as used in the academic literature as "a movement that uses environmental and ecological conservationist talking points to push an ideology of ethnic or racial separatism".[26] This is supported by Blair Taylor statement that ecofascism refers to "groups and ideologies that offer authoritarian, hierarchical, and racist analyses and solutions to environmental problems".[27] Similarly, extremism researchers Brian Hughes, Dave Jones, and Amarnath Amarasingam state how ecofascism is less a coherent ideology and more a cultural expression of mystical, anti-humanist romanticism.[28] This is further supported by Maria Darwish in her research into the Nordic Resistance Movement where while there is concern for environmental issues they are "a concern for Neo-Nazis only in so far as it supports and popularizes the backstage mission of the NRM", that is the implementation of a fascist regime,[29] and Jacob Blumenfeld stating "ecofascism names a specific far-right ideology that rationalizes white supremacist violence by invoking imminent ecological collapse and scarce natural resources".[30]

Borrowing from the "watermelon" analogy of eco-socialism, Berggruen Institute scholar Nils Gilman has coined the term "avocado politics" for eco-fascism, being "green on the outside but brown(shirt) at the core".[31][32][33]

Ideological origins[edit]

Madison Grant[edit]

Sometimes dubbed the "founding father" of ecofascism,[34][35] Madison Grant was a pioneer of conservationism in America in the late 19th and early 20th century. Grant is credited as a founder of modern wildlife management. Grant built the Bronx River Parkway, was a co-founder of the American Bison Society, and helped create Glacier National Park, Olympic National Park, Everglades National Park and Denali National Park. As president of the New York Zoological Society, he founded the Bronx Zoo in 1899.[36]

In addition to his conservationist work, Grant was a trenchant racist.[37][38] In 1906, Grant supported the placement of Ota Benga, a member of the Mbuti people who was kidnapped, removed from his home in the Congo, and put on display in the Bronx Zoo as an exhibit in the Monkey House.[34][35] In 1916, Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a work of pseudoscientific literature which claimed to give an account of the anthropological history of Europe.[39] The book divides Europeans into three races; Alpines, Mediterraneans and Nordics, and it also claims that the first two races are inferior to the superior Nordic race, which is the only race which is fit to rule the earth. Adolf Hitler would later describe Grant's book as "his bible" and Grant's "Nordic theory" became the bedrock of Nazi racial theories.[40] Additionally, Grant was a eugenicist: He cofounded and was the director of the American Eugenics Society and he also advocated the culling of the unfit from the human population.[41][42][43] Grant concocted a 100-year plan to perfect the human race, a plan in which one ethnic group after another would be killed off until racial purity would be obtained.[34] Grant campaigned for the passage of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and he also campaigned for the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, which drastically reduced the number of immigrants from eastern Europe and Asia who were allowed to enter the United States.[44][42]

In the modern era, Grant's ideas have been cited by advocates of far-right politics such as Richard Spencer[36] and Anders Breivik.[35][45][46]

Nazism[edit]

The authors Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier suggest that the synthesis of fascism and environmentalism began with Nazism, stating that 19th and 20th century Germany was an early center of ecofascist thought, finding its antecedents in many prominent natural scientists and environmentalists, including Ernst Moritz Arndt, Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, and Ernst Haeckel.[47] With the works and ideas of such individuals being later established as policies in the Nazi regime.[48] This is supported by other researchers who identify the Völkisch movement as an ideological originator of later ecofascism.[49][50] In Biehl and Staudenmaier's book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience, they note the Nazi Party's interest in ecology, and suggest their interest was "linked with traditional agrarian romanticism and hostility to urban civilization".[51][52][53] With Zimmerman pointing to the works of conservationist and Nazi Walther Schoenichen as having pertinence to later ecofascism and similarities to developments in deep ecological understanding.[54] During the Nazi rise to power, there was strong support for the Nazis among German environmentalists and conservationists.[55] Richard Walther Darré, a leading Nazi ideologist and Reich Minister of Food and Agriculture who invented the term "Blood and Soil", developed a concept of the nation having a mystic connection with their homeland, and as such, the nation was dutybound to take care of the land.[56] This was supported by other Nazi theorists such as Alfred Rosenberg who wrote of how society's move from agricultural systems to industrialised systems broke their connection to nature and contributed to the death of the Volk.[51] Similar sentiments are found in speeches from Fascist Italy’s Minister of Agriculture Giuseppe Tassinari.[57] Because of this, modern ecofascists cite the Nazi Party as an origin point of ecofascism.[58][59][60] Beyond Darré, Rudolf Hess and Fritz Todt are viewed as representatives of environmentalism within the Nazi party.[61][62] Roger Griffin has also pointed to the glorification of wildlife in Nazi art and ruralism in the novels of the fascist sympathizers Knut Hamsun and Henry Williamson as examples.[63]

After the outlawing of the neo-nazi Socialist Reich Party, one of its members August Haußleiter moved towards organising within the environmental and anti-nuclear movements, going on to become a founding member of the German Green Party. When green activists later uncovered his past activities in the neo-nazi movement, Haußleiter was forced to step down as the party's chairman, although he continued to hold a central role in the party newspaper.[64] As efforts to expel nationalist elements within the party continued, a conservative faction split off and founded the Ecological Democratic Party, which became noted for persistent holocaust denial, rejection of social justice and opposition to immigration.[65]

Savitri Devi[edit]

The French-born Greek fascist Savitri Devi (born Maximiani Julia Portas) was a prominent proponent of Esoteric Nazism and deep ecology.[67] A fanatical supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Party from the 1930s onwards, she also supported animal rights activism and was a vegetarian from a young age. In her works, she espoused ecologist views, such as the Impeachment of Man (1959), in which she espoused her views on animal rights and nature.[68][69] In accordance with her ecologist views, human beings do not stand above the animals; instead, humans are a part of the ecosystem and as a result, they should respect all forms of life, including animals and the whole of nature. Because of her dual devotion to Nazism and deep ecology, she is considered an influential figure in ecofascist circles.[70][71]

Malthusianism[edit]

Malthusian ideas of overpopulation have been adopted by ecofascists,[72] using Malthusian rationale in anti-immigration arguments[73] and seeking to resolve the perceived global issue by enforcing population control measures on the global south and racial minorities in white majority countries.[74] Such Malthusian ideas are often paired with Social Darwinist and eugenicist views.[75][43][76]

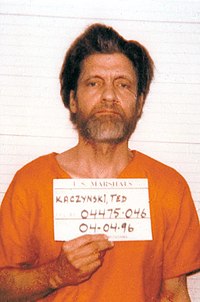

Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber[edit]

Ted Kaczynski, better known as "The Unabomber", is cited as a figure who was highly influential in the development of ecofascist thought, and features prominently in contemporary ecofascist propaganda.[77] Between 1978 and 1995 Kaczynski instigated a terrorist bombing campaign aimed at inciting a revolution against modern industrial society,[78] in the name of returning humanity to a primitive state he suggested offered humanity more freedom while protecting the environment. In 1995 Kaczynski offered to end his bombing campaign if The Washington Post or The New York Times would publish his 35,000-word Unabomber manifesto. Both newspapers agreed to those terms. The manifesto railed not only against modern industrial society but also against "modern leftists", whom Kaczynski defined as "mainly socialists, collectivists, 'politically correct' types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like".[79][80]

Because of Kaczynski's intelligence and because of his ability to write in a high-level academic tone, his manifesto was given serious consideration upon its release and it became highly influential, even amongst those who severely disagreed with his use of violence. Kaczynski's staunchly radical pro-green, anti-left work was quickly absorbed into ecofascist thought.[81][82]

Kaczynski also criticized right wing activists who complained about the erosion of traditional social mores because they supported technological and economic progress, a view which he opposed. He stated that technology erodes traditional social mores that conservatives and right wingers want to protect, and he referred to conservatives as fools.[83]

Although Kaczynski and his manifesto have been embraced by ecofascists,[81] he rejected 'fascism',[84] including specifically "the 'ecofascists'", describing 'ecofascism' itself as 'an aberrant branch of leftism':[85][86]

The true anti-tech movement rejects every form of racism or ethnocentrism. This has nothing to do with "tolerance," "diversity," "pluralism," "multiculturalism," "equality," or "social justice." The rejection of racism and ethnocentrism is - purely and simply - a cardinal point of strategy.[85]

In his manifesto, Kaczynski wrote that he considered fascism a "kook ideology" and he also wrote that he considered Nazism "evil".[84] Kaczynski never tried to align himself with the far-right at any point before or after his arrest.[84]

In 2017, Netflix released a dramatisation of Kaczynski's life, titled Manhunt: Unabomber. Once again, the popularity of the show thrust Kaczynski and his manifesto into the public's mind and it also raised the profile of ecofascism.[87][59][84]

Garrett Hardin, Pentti Linkola, and "Lifeboat Ethics"[edit]

Two figures influential in ecofascism are Garrett Hardin[88] and Pentti Linkola,[89][90] both of whom were proponents of what they refer to as "Lifeboat Ethics".[91] Hardin was an American ecologist often described as a white nationalist,[92][93][94] whilst Linkola was a Finnish ecologist and radical Malthusian[95] accused of being an active ecofascist[96] who actively advocated ending democracy and replacing it with dictatorships that would use totalitarian and even genocidal tactics[97] to end climate change.[98][99][100] Both men used versions of the following analogy to illustrate their viewpoint:

| “ | What to do, when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and there is only one lifeboat? When the lifeboat is full, those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship's axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides.[87][59] | ” |

Renaud Camus[edit]

Renaud Camus' conspiracy theory, the Great Replacement, has been influential on ecofascism, being referenced explicitly in multiple manifestos and had its ideas relayed in others.[101] In the conspiracy theory the "native" white populations of western countries are being replaced by non-white populations as a directed political effort.[102][103]

Association with violence[edit]

Ecofascist violence has occurred since the 21st century,[104][105] with academics and researchers warning that as ecological crises worsen and remain unaddressed, support for ecofascism and violence in the name of ecofascism will increase.[106]

Tree of Life Synagogue shooter https://earthworks.org/blog/eco-fascism-a-tangible-present-danger/

In December 2020, the Swedish Defence Research Agency released a report on ecofascism. The paper argued that ecofascism is intimately tied to the ideology of accelerationism, and ecofascists nearly exclusively choose terror tactics over the political approach.[104] Further, the SDRA argues not all ecofascist mass shooters have been recognized as such: Pekka-Eric Auvinen who shot eight people in Finland in 2007 before killing himself adhered to the ideology according to his manifesto titled "The Natural Selector's Manifesto".[107][108] He advocated "total war against humanity" due to the threat humanity posed to other species. He wrote that death and killing is not a tragedy, as it constantly happens in nature between all species. Auvinen also wrote that the modern society hinders "natural justice" and that all inferior "subhumans" should be killed and only the elite of humanity be spared. In one of his YouTube videos Auvinen paid tribute to the prominent deep ecologist Pentti Linkola.[104]

James Jay Lee, the eco-terrorist who took several hostages at the Discovery Communications headquarters on 1 September 2010, was described as an ecofascist by Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center.[109]

Anders Breivik committed the 2011 Norway attacks on 22 July 2011, in which he killed eight people by detonating a van bomb at Regjeringskvartalet in Oslo, and then killed 69 participants of a Workers' Youth League (AUF) summer camp, in a mass shooting on the island of Utøya.[110][111][112] While dismissive of climate change, Breivik’s manifesto was concerned with the carrying capacity of the planet,[113] taking inspiration from Kaczynski[114] and Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race.[46] Breivik’s solution to this perceived problem was to cap the global population at 2.5 billion people, with the reduction in the global population being forced upon the global south.[113] Through his actions he sought to inspire other terrorist attacks,[115] and was an inspiration for later ecofascist terrorists.[116]

William H. Stoetzer, a member of the Atomwaffen Division, an organisation responsible for at least eight murders, was active in the Earth Liberation Front as late as 2008 and joined Atomwaffen in 2016.[117]

Brenton Tarrant, the Australian-born perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand described himself as an ecofascist,[118] ethno-nationalist, and racist[119][120] in his manifesto The Great Replacement, named after a far-right conspiracy theory[121] originating in France. In the manifesto Tarrant specifically mentions Breivik as an ideological and operational influence.[122] Researchers point to Tarrant's terrorist attack as the moment when discussion of ecofascism moved from academic and specialist circles into the mainstream.[123][124] Jordan Weissmann, writing for Slate, describes the perpetrator's version of ecofascism as "an established, if somewhat obscure, brand of neo-Nazi"[125] and quotes Sarah Manavis of New Statesman as saying, "[Eco-fascists] believe that living in the original regions a race is meant to have originated in and shunning multiculturalism is the only way to save the planet they prioritise above all else".[125][126] Similarly, Luke Darby clarifies it as: "eco-fascism is not the fringe hippie movement usually associated with ecoterrorism. It's a belief that the only way to deal with climate change is through eugenics and the brutal suppression of migrants."[35]

Patrick Crusius, the perpetrator of the 2019 El Paso shooting wrote a similar manifesto, professing support for Tarrant.[127] Posted to the online message board 8chan,[128] it blames immigration to the United States for environmental destruction,[129][27] saying that American lifestyles were "destroying the environment",[130] invoking an ecological burden to be borne by future generations,[131][35] and concluding that the solution was to "decrease the number of people in America using resources".[130] Crusius outlined how he took inspiration from Tarrant and Breivik in his manifesto.[132][133][134] Crusius and Tarrant also inspired Philip Manshaus who attacked a mosque in Norway in 2019.[135][136] The El Paso terrorist attack catapulted into public awareness the "greening of hate" that has long haunted the American environmental movement. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/4-november-december/feature/eco-fascism-uncovered-el-paso-texas

The Swedish self-identified ecofascist Green Brigade is an eco-terrorist group linked to The Base that is responsible for multiple mass murder plots.[139][140][124] The Green Brigade has been responsible for arson attacks against targets deemed to be enemies of nature,[8][141] like an attack on a mink farm that caused multi-million-dollar damages.[140][142] Two members were arrested by Swedish police, allegedly planning assassinating judges and bombings.[143][144]

In June 2021, the Telegram-based Terrorgram collective published an online guide with incitements for attacks on infrastructure and violence against minorities, police, public figures, journalists, and other perceived enemies. In December 2021, they published a second document containing ideological sections on accelerationism, white supremacy, and ecofascism.[145][146][147]

In an interview with a blog Maldición Eco-Extremista a leader of the anarchist eco-extremist group Individualists Tending to the Wild (ITS) claimed to have taken some organisational influence from the fascist accelerationist terrorist group Order of Nine Angles, while disavowing the group's fascism. However, Foundation for Defense of Democracies characterized ITS's literature as ecofascist.[148][149]

Payton S. Gendron, the instigator of the 2022 Buffalo shooting, also wrote a manifesto self-describing as "an ethno-nationalist eco-fascist national socialist" within it and also professing support for far-right shooters from Tarrant[150] and Dylann Roof to Breivik and Robert Bowers.[151][152] Later in 2022, the Terrorgram collective released another publication, with analysts believing it would likely inspire further "Buffalo shootings".[153]

Criticism[edit]

The deep ecologic activist and "left biocentrism" advocate David Orton stated in 2000 that the term is pejorative in nature and it has "social ecology roots, against the deep ecology movement and its supporters plus, more generally, the environmental movement. Thus, 'ecofascist' and 'ecofascism', are used not to enlighten but to smear." Orton argued that "it is a strange term/concept to really have any conceptual validity" as there has not "yet been a country that has had an "eco-fascist" government or, to my knowledge, a political organization which has declared itself publicly as organized on an ecofascist basis."[154][a]

Accusations of ecofascism have often been made but are usually strenuously denied.[154][157] Left wing critiques view ecofascism as an assault on human rights, as in social ecologist Murray Bookchin's use of the term.[158]

Deep ecology[edit]

Deep ecology is an environmental philosophy that promotes the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility to human needs. It has long been linked to fascist ideologies, both by critics and fascist proponents.[54][159] In certain texts, the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, a leading voice of the "deep ecology" movement, opposes environmentalism and humanism, even proclaiming, in imitation of a famous phrase of the Marquis de Sade, "Écologistes, encore un effort pour devenir anti-humanistes" ("Ecologists, another effort to become anti-humanists!").[160] Luc Ferry, in his anti-environmentalist book Le Nouvel Ordre écologique published in 1992, particularly incriminated deep ecology as being an anti-humanist ideology bordering on Nazism.[161][162] Modern ecofascism has been described as a deep ecological philosophy combined with antihumanism and an accelerationist stance.[163]

Bookchin's critique of deep ecology[edit]

Murray Bookchin criticizes the political position of deep ecologists[164] such as David Foreman:

There are barely disguised racists, survivalists, macho Daniel Boones, and outright social reactionaries who use the word ecology to express their views, just as there are deeply concerned naturalists, communitarians, social radicals, and feminists who use the word ecology to express theirs... It was out of this former kind of crude eco-brutalism that Hitler, in the name of "population control," with a racial orientation, fashioned theories of blood and soil...

The same eco-brutalism now reappears a half-century later among self-professed deep ecologists who believe that Third World peoples should be permitted to starve to death and that desperate Indian immigrants from Latin America should be excluded by the border cops from the United States lest they burden "our" ecological resources.[158]

Sakai on "natural purity"[edit]

Such observations among the left are not exclusive to Bookchin. In his review of Anna Bramwell's biography of Richard Walther Darré, political writer J. Sakai and author of Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat, observes the fascist ideological undertones of natural purity.[165] Prior to the Russian Revolution, the tsarist intelligentsia was divided on the one hand between liberal "utilitarian naturalists", who were "taken with the idea of creating a paradise on earth through scientific mastery of nature" and influenced by nihilism as well as Russian zoologists such as Anatoli Petrovich Bogdanov; and, on the other, "cultural-aesthetic" conservationists such as Ivan Parfenevich Borodin, who were influenced in turn by German Romantic and idealist concepts such as Landschaftspflege and Naturdenkmal.[166]

Narrowness of the label[edit]

Political scientist Balša Lubarda has criticised the use of the term "ecofascism" as not sufficiently covering and describing the wider network of ideologies and systems that feed into ecofascist action, suggesting the term "far-right ecologism" (FRE) instead.[167][168][169] Lubarda is supported by researcher Bernhard Forchtner who emphasises ecofascism's existence as a fringe ideology that has had little impact on the wider far-right's interaction with environmentalism.[170][171]

Disavowment[edit]

As ecofascism has become more prevalent various environmental groups and organisations have publicly disavowed the ideology and those who subscribe to it.[172]

Far-right green movements[edit]

In recent years there has been a greater proliferation in ecofascist groups globally in line with the proliferation of ecofascist rhetoric.[173][174]

Australia[edit]

Australia has seen an increasing prominence of ecofascism among its far-right groups in recent years.[175][176]

Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name (see the help page).

- Ecofascism – are far-right extremists the new environmentalists?

- Beware far-right arguments disguised as environmentalism

- From Brownshirts to Greenshirts: Understanding Ecofascism in a Time of Climate Crisis

- Surviving Climate Change and Ecofascism

- Global Heating and the Australian Far Right

- Feature | Tasmania first: ecofascism and the settler invasion fantasy

Austria[edit]

The Greens of Austria (DGÖ) had been founded in 1982 by the former NDP official Alfred Bayer to use the popularity of the green movement at the time for the purposes of the NDP. The party managed to win a number of municipal seats in the mid-1980s but in 1988 the Constitutional Court banned the party on grounds of Neo-Nazism alongside a parallel ban on the NDP.[177]

Finland[edit]

The neo-fascist Blue-and-Black Movement includes ecofascist policy goals, stating that they aim to protect the nature and biodiversity of Finland, and to live in harmony with nature, ending ritual slaughter, fur-farming and animal testing.[178]

France[edit]

Nouvelle Droite movement[edit]

The European Nouvelle Droite movement, developed by Alain de Benoist and other individuals involved with the GRECE think tank, have also combined various left-wing ideas, including green politics, with right-wing ideas such as European ethnonationalism.[63][21][179] Various other far-right figures have taken the lead from de Benoist, providing an appeal to nature in their politics, including: Guillaume Faye, Renaud Camus, and Hervé Juvin.[21] From the nineteenth century to Zemmour, ecofascism contaminates the political debate (reporterre.net)

Génération identitaire[edit]

In 2020, following articles from self-described ecofascist Piero San Giorgio, a spokesperson for Génération identitaire, Clément Martin, advocated for zones identitaires à défendre, ethnically homogenous zones to be violently defended in order to protect the environment.[21]

Marine Le Pen[edit]

Germany[edit]

Staudenmaier points to how from the post-war period in Germany an ecofascist section has always been present in the German far-right, though as a minor peripheral section,[182][183] with others pointing out a long history of right-wing individuals and groups being present in the environmental and green movement in Germany.[184]

The NPD[edit]

The National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), a German Nationalist far-right party, has long sought to use the green movement.[185] This is one of many strategies the party has used to try to gain supporters.[186]

The German far-right has published the magazine Umwelt & Aktiv, that masquerades as a garden and nature publication but intertwines garden tips with extremist political ideology.[187][188][189] This is known as a “camouflage publication” in which the NPD has spread its mission and ideologies through a discrete source and made its way into homes they otherwise wouldn’t.[186] Right-wing environmentalists are settling in the northern regions of rural Germany and are forming nationalistic and authoritarian communities which produce honey, fresh produce, baked goods, and other such farm goods for profit. Their ideology is centered around “blood and soil” ruralism in which they humanely raise produce and animals for profit and sustenance. Through their support of this operation, and the backing of many others, it’s reported that the NPD is trying to wrestle the green movement, which has been dominated by the left since the 1980s, back from the left through these avenues.[190]

It's difficult to know if when one is buying local produce or farm fresh eggs from a farmer at their stand, they're supporting a right-wing agenda. Various efforts are being made to halt or slow the infiltration of right-wing ecologists into the community of organic farmers such as brochures about their communities and common practices. However, as the organic cultivation organisation, Biopark, demonstrates with their vetting process, it's difficult to keep people out of communities because of their ideologies. Biopark specifies that they vet based on cultivation habits, not opinions or doctrines, especially when they're not explicitly stated.[186]

Collegium Humanum[edit]

The Collegium Humanum was an ecofascist organisation in Germany from 1963 to 2008. It was established in 1963[191] as a club, was first active in the German environmental movement, then from the early 1980s became a far-right political organisation and was banned in 2008 by the Federal Minister of the Interior Wolfgang Schäuble due to "continued denial of the Holocaust".[192]

Other groups[edit]

The term is also used to a limited extent within the Neue Rechte.[193] The neo-Artamans have been identified as ecofascists in their attempts to revive the agrarian and völkisch traditions of the Artaman League in communes that they have built up since the 1990s.[194][186]

Hungary[edit]

Following the fall of Communism in Hungary at the end of the 1980s, one of the new political parties that emerged in the country was the Green Party of Hungary. Initially having a moderate centre-right green outlook, after 1993 the party adopted a radical anti-liberal, anti-communist, anti-Semitic and pro-fascist stance, paired with the creation of a paramilitary wing.[195] This ideological swing resulted in many members breaking off from the party to form new green parties, first with Green Alternative in 1993 and secondly with Hungarian Social Green Party in 1995. Each green party remained on the political fringe of Hungarian politics and petered out over time.[196] It was not until the formation of LMP – Hungary's Green Party in the 2010s that green politics in Hungary consolidated around a single green party.

The far-right Hungarian political party Our Homeland Movement has adopted some elements of environmentalism, and commonly refers to itself as the only true green party;[181] for example, the party has called on Hungarians to show patriotism by supporting the removal of pollution from the Tisza River while simultaneously placing the blame on the pollution on Romania and Ukraine.[197] Similarly, elements of the far-right Sixty-Four Counties Youth Movement proscribe themselves to the "Eco-Nationalist" label, with one member stating "no real nationalist is a climate denialist".[198]

India[edit]

Narendra Modi's leadership of India with the Bharatiya Janata Party seeks to install a complete system of Hindutva,[199] with repression of racial and religious minorities and caste discrimination.[200] Since 2018 Modi has been increasingly viewed as an environmental champion and used rhetoric about protecting the environment to greenwash his image and the image of his party.[201][202][203]

International[edit]

Greenline Front is an international network of ecofascists which originated in Eastern Europe, with chapters in a variety of countries such as Argentina, Belarus, Chile, Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Spain and Switzerland.[204]

Serbia[edit]

Leviathan Movement promotes ecology and protects animals from cruelty by, among other things, saving them from abusers. Leviathan has been reported as an ideologically neo-fascist[205] and neo-nazi group.[206] They used to share an office with the Serbian Right, a far-right political party, and Leviathan ’s leader, Pavle Bihali, is seen in pictures on his social media accounts posing with neo-Nazis.[207]

Sweden[edit]

The Nordic Resistance Movement, a pan-Nordic[208][209] neo-Nazi[210] movement in the Nordic countries and a political party in Sweden has been continually described as ecofascist,[211][212] and have declared themselves as the "new green party" of the Nordics.[213] In their English-language literature they continually link immigration to environmental degradation

Switzerland[edit]

In Switzerland, the initiators of the Ecopop initiative were accused of eco-fascism by FDFA State Secretary Yves Rossier at a Christian Democratic People's Party of Switzerland event on 11 January 2013.[214] However, after threatening to sue, Rossier apologized for the allegation.[215]

United Kingdom[edit]

There is also a historic tradition between the far-right and environmentalism in the UK.[216][217] Throughout its history, the far-right British National Party has flirted on and off with environmentalism. During the 1970s the party's first leader John Bean expressed support for the emerging environmentalist movement in the pages of the party's newspaper and suggested the primary cause of pollution as overpopulation, and therefore immigration into Britain must be halted.[218][46] During the 2000s the BNP sought to position itself as the "only 'true' green party in the United Kingdom, dedicating a significant portion of their manifestos to green issues. During an appearance on BBC One's Question Time in October 2009, then-leader Nick Griffin proclaimed:

Unlike the fake "Greens" who are merely a front for the far left of the Labour regime, the BNP is the only party to recognise that overpopulation – whose primary driver is immigration, as revealed by the government's own figures – is the cause of the destruction of our environment. Furthermore, the BNP's manifesto states that a BNP government will make it a priority to stop building on green land. New housing should wherever possible be built on derelict "brown land".[219]

The Guardian criticised Griffin's claims that himself and the BNP were truly environmentalists at heart, suggesting it was merely a smokescreen for anti-immigrant rhetoric and pointed to previous statements by Griffin in which he suggested that climate change was a hoax.[219] These suspicions seemed to be proven correct when in December 2009 the BNP released a 40-page document denying that global warming is a "man-made" phenomenon.[220] The party reiterated this stance in 2011, as well as making claims that wind farms were causing the deaths of "thousands of Scottish pensioners from hypothermia".[221] John Bean a far-right activist and politician, the first leader of the BNP and latterly a leader within the National Front, wrote regularly in the National Front’s magazine about the problems of pollution and environmental degradation tying them to ideas of overpopulation and immigration.[218]

In Scotland, former UKIP candidate and activist Alistair McConnachie, who has questioned the Holocaust, founded the Independent Green Voice in 2003,[222] and multiple ex-BNP members and activists have stood as candidates for the party.[223]

United States[edit]

During the 1990s a highly militant environmentalist subculture called Hardline emerged from the straight edge hardcore punk music scene and established itself in a number of cities across the US. Adherents to the Hardline lifestyle combined the straight edge belief in no alcohol, no drugs, no tobacco with militant veganism and advocacy for animal rights. Hardline touted a biocentric worldview that claimed to value all life, and therefore opposed abortion, contraceptives, and sex for any purpose other than procreation. On this same line, Hardline opposed homosexuality as "unnatural" and "deviant”.[224] Hardline groups were highly militant; In 1999 Salt Lake City grouped Hardliners as a criminal gang and suggested they were behind dozens of assaults in the metro area.[225] That same year CBS News reported that Hardliners were behind the firebombing of fast food outlets and clothing stores selling leather items, and attributed 30 attacks to Hardliners.[226] The Hardline subculture dissolved after the 1990s.