Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 November 1632 |

| Died | 21 February 1677 (aged 44) The Hague, Dutch Republic |

| Other names | Benedictus de Spinoza |

| Education |

|

| Era | |

| Region | |

| School | |

Main interests | |

| Signature | |

Baruch (de) Spinoza[b] (24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin. As a forerunner of the Age of Reason, Spinoza significantly influenced modern biblical criticism, 17th-century Rationalism, and contemporary conceptions of the self and the universe, establishing himself as one of the most important and radical philosophers of the early modern period.[15] He was influenced by Stoicism, Maimonides, Niccolò Machiavelli, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, and a variety of heterodox Christian thinkers of his day.[16]

Spinoza was born in Amsterdam to a marrano family that had left Portugal for a more tolerant Amsterdam. He had a traditional education for a Jewish boy, learning Hebrew and studying the sacred texts. He was part of the wealthy Portuguese Jewish community, where his merchant immigrant father was a prominent member. As a young man, Spinoza was permanently expelled from the Jewish community for defying rabbinic authorities and disputing Jewish beliefs. After his expulsion in 1656, he did not affiliate with any religion, instead focusing on philosophical study. He had a dedicated following, or philosophical sect, who met to discuss his writings.[17]

Spinoza challenged the divine origin of the Hebrew Bible, the nature of God, and the earthly power wielded by religious authorities, Jewish and Christian alike. He was frequently called an atheist by contemporaries, although nowhere in his work does Spinoza argue against the existence of God.[18][19] This can be explained by the fact that, unlike contemporary 21st-century scholars, “when seventeenth-century readers accused Spinoza of atheism, they usually meant that he challenged doctrinal orthodoxy, particularly on moral issues, and not that he denied God’s existence."[20] His theological studies were inseparable from his thinking on politics; he is grouped with Hobbes, John Locke, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Immanuel Kant, who "helped establish the genre of political writing called secular theology."[21]

Spinoza's philosophy encompasses nearly every area of philosophical discourse, including metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, ethics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of science. With an enduring reputation as one of the most original and influential thinkers of the seventeenth century, Rebecca Goldstein dubbed him "the renegade Jew who gave us modernity."[22]

Biography[edit]

Family background[edit]

Spinoza's ancestors, adherents of Crypto-Judaism, faced persecution during the Portuguese Inquisition, enduring torture and public displays of humiliation.[24] In 1597, his paternal grandfather's family left Vidigueira for Nantes and lived as New Christians, eventually transferring to Holland for an unknown reason.[25] His maternal ancestors were a leading Oporto commercial family,[26] and his maternal grandfather was a foremost merchant who drifted between Judaism and Christianity.[27] Spinoza was raised by his grandmother from ages six to nine and probably learned much about his family history from her.[28]

Spinoza's father Michael was a prominent and wealthy merchant in Amsterdam with a business that had wide geographical reach.[29] In 1649, he was elected to serve as an administrative officer of the recently united congregation Talmud Torah.[30] He married his cousin Rachael d’Espinosa, daughter of his uncle Abraham d’Espinosa, who was also a community leader and Michael's business partner.[31] Marrying cousins was common in the Portuguese Jewish community then, giving Michael access to his father-in-law's commercial network and capital.[32] Rachel's children died in infancy, and she died in 1627.[33][32]

After the death of Rachel, Michael married Hannah Deborah, with whom he had five children. His second wife brought a dowry to the marriage that was absorbed into Michael's business capital instead of being set aside for her children, which may have caused a grudge between Spinoza and his father.[34] The family lived on the artificial island on the south side of the River Amstel, known as the Vlooienburg, at the fifth house along the Houtgracht canal.[23] The Jewish quarter was not formally divided. The family lived close to the Bet Ya'acov synagogue, and nearby were Christians, including the artist Rembrandt.[35] Miriam was their first child, followed by Isaac who was expected to take over as head of the family and the commercial enterprise but died in 1649.[34] Baruch Espinosa, the third child, was born on 24 November 1632 and named as per tradition for his maternal grandfather.[9]

Spinoza's younger brother Gabriel was born in 1634, followed by another sister Rebecca. Miriam married Samuel de Caceres but died shortly after childbirth. According to Jewish practice, Samuel had to marry his former sister-in-law Rebecca.[36] Following his brother's death, Spinoza's place as head of the family and its business meant scholarly ambitions were pushed aside.[29] Spinoza's mother, Hannah Deborah, died when Spinoza was six years old. Michael's third wife, Esther, raised Spinoza from age nine; she lacked formal Jewish knowledge due to growing up a New Christian and only spoke Portuguese at home. The marriage was childless.[37] Spinoza's sister Rebecca, brother Gabriel, and nephew eventually migrated to Curaçao, and the remaining family joined them after Spinoza's death.[36]

Uriel da Costa's early influence[edit]

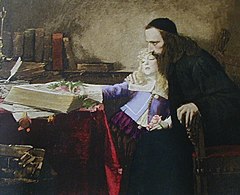

Through his mother, Spinoza was related to the philosopher Uriel da Costa, who stirred controversy in Amsterdam's Portuguese Jewish community.[38] Da Costa questioned traditional Christian and Jewish beliefs, asserting that, for example, their origins were based on human inventions instead of God's revelation. His clashes with the religious establishment led to his excommunication twice by rabbinic authorities, who imposed humiliation and social exclusion.[39] In 1639, as part of an agreement to be readmitted, da Costa had to prostrate himself for worshippers to step over him. He died in 1640, reportedly committing suicide.[40]

During his childhood, Spinoza was likely unaware of his family connection with Uriel da Costa; still, as a teenager, he certainly heard discussions about him.[41] Steven Nadler explains that, although da Costa died when Spinoza was eight, his ideas shaped Spinoza's intellectual development. Amsterdam’s Jewish communities long remembered and discussed da Costa's skepticism about organized religion, denial of the soul's immortality, and the idea that Moses didn't write the Torah, influencing Spinoza's intellectual journey.[42]

School days and the family business[edit]

Spinoza attended the Talmud Torah school adjoining the Bet Ya'acov synagogue, a few doors down from his home, headed by the senior Rabbi Saul Levi Morteira.[43][44] Instructed in Spanish, the language of learning and literature, students in the elementary school learned to read the prayerbook and the Torah in Hebrew, translate the weekly section into Spanish, and study Rashi's commentary.[45] Spinoza's name does not appear on the registry after age fourteen, and, likely, he never studied with rabbis such as Manasseh ben Israel and Morteira. Spinoza possibly went to work around fourteen and almost certainly was needed in his father's business after his brother died in 1649.[46]

During the First Anglo-Dutch War, much of the Spinoza firm's ships and cargo were captured by English ships, severely affecting the firm's financial viability. The firm was saddled with debt by the war's end in 1654 due to its merchant voyages being intercepted by the English, leading to its decline.[47][48] Spinoza's father died in 1654, making him the head of the family, responsible for organizing and leading the Jewish mourning rituals, and in a business partnership with his brother of their inherited firm.[49] As Spinoza's father had poor health for some years before his death, he was significantly involved in the business, putting his intellectual curiosity on hold.[50] Until 1656, he continued financially supporting the synagogue and attending services in compliance with synagogue conventions and practice.[51] By 1655, the family's wealth had evaporated and the business effectively ended.[50]

In March 1656, Spinoza went to the city authorities for protection against debts in the Portuguese Jewish community. To free himself from the responsibility of paying debts owed to his late father, Spinoza appealed to the city to declare him an orphan;[52] since he was a legal minor, not understanding his father's indebtedness would remove the obligation to repay his debts and retrospectively renounce his inheritance.[53] Though he was released of all debts and legally in the right, his reputation as a merchant was permanently damaged in addition to violating a synagogue regulation that business matters are to be arbitrated within the community.[54][52]

Study circle[edit]

Sometime between 1654 and 1658, Spinoza began to study Latin with Franciscus van den Enden, a former Jesuit who was a political radical and likely introduced Spinoza to scholastic and modern philosophy, including Descartes. Spinoza adopted the Latin name, Benedictus de Spinoza, began boarding with Van den Enden, and began teaching in his school.[c][56][57]

During this period, Spinoza also became acquainted with the Collegiants, an anti-clerical sect of Remonstrants with tendencies towards rationalism, and with the liberal faction among the Mennonites who had existed for a century but were close to the Remonstrants.[58] Many of his friends belonged to dissident Christian groups that met regularly as discussion groups and typically rejected the authority of established churches and traditional dogmas.[59] In the second half of the 1650s and the first half of the 1660s Spinoza became acquainted with several persons who would themselves emerge as unorthodox thinkers: this group, known as the Spinoza Circle, included Pieter Balling, Jarich Jelles, Lodewijk Meyer, Johannes Bouwmeester and Adriaen Koerbagh.

Expulsion from the Jewish community[edit]

Amsterdam was tolerant of religious diversity so long as it was practiced discreetly, and Jews were not legally confined to a ghetto. The community was concerned with protecting its reputation and not associating with Spinoza lest his controversial views provide the basis for possible persecution or expulsion.[60] Spinoza did not openly break with Jewish authorities until his father died in 1654 when he became public and defiant, resulting from lengthy and stressful religious, financial, and legal clashes involving his business and synagogue, such as when Spinoza violated synagogue regulations by going to city authorities rather than resolving his disputes within the community to free himself from paying his father's debt.[52]

On 27 July 1656, the Talmud Torah community leaders, which included Aboab de Fonseca,[61] issued a writ of herem against the 23-year-old Spinoza.[62][63] Spinoza's censure was the harshest ever pronounced in the community, carrying tremendous emotional and spiritual impact.[64] The exact reason for expelling Spinoza is not stated, only referring to his "abominable heresies", "monstrous deeds", and the testimony of witnesses "in the presence of the said Espinoza".[65] Even though the Amsterdam municipal authorities were not directly involved in Spinoza's censure itself, the town council expressly ordered the Portuguese-Jewish community to regulate their conduct and ensure that the community kept a strict observance of Jewish law.[66] Other evidence shows that the danger of upsetting the civil authorities was not far from mind, such as bans adopted by the synagogue on public weddings or funeral processions and on discussing religious matters with Christians, lest such activity might "disturb the liberty we enjoy".[67]

Before the expulsion, Spinoza had not published anything or written a treatise; if Spinoza was voicing his criticism of Judaism that later appeared through his philosophical works, such as Part I of Ethics, then there can be no wonder that he was severely punished.[68] He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his Theological-Political Treatise that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. He had effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656 because of his bleak financial situation.[69] Unlike most censures issued by the Amsterdam congregation, since the censure did not lead to repentance, it was never rescinded. After the censure, Spinoza is said to have written an Apologia in Spanish to the community leaders, defending his views and condemning the rabbis, but it is now lost.[70]

Spinoza's expulsion from the Jewish community did not lead him to convert to Christianity. Spinoza maintained a close association with the Collegiants and Quakers, moved to a town near the Collegiants' headquarters, and was buried at the Protestant Church, Nieuwe Kerk, The Hague, since burial was a sectarian matter and he was ineligible to be buried in the Jewish cemetery.[71] Spinoza did not maintain a sense of Jewish identity because, in his view, being a secular and assimilated Jew was nonsense.[72]

Career as a philosopher[edit]

Spinoza has been called "the reticent radical", who proceeded cautiously for the next 22 years, quietly writing and studying as a private scholar.[73] He initially taught in the school of his Latin tutor, Franciscus van den Enden, with whom he boarded for a time. Later upon leaving Amsterdam, he earned a living as a lens grinder. He also received some financial assistance from supporters of his intellectual stance. After the herem, the Amsterdam municipal authorities expelled Spinoza from Amsterdam, "responding to the appeals of the rabbis, and also of the Calvinist clergy, who had been vicariously offended by the existence of a free thinker in the synagogue".

He spent a brief time in or near the village of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel, where the Portuguese Jews had been allowed to buy land to establish Beth Haim, a Jewish burying ground. Spinoza's parents and grandparents are buried there. Spinoza returned soon afterward to Amsterdam and lived there quietly for several years, giving private philosophy lessons and grinding lenses, before leaving the city in 1660 or 1661.[70] During this time in Amsterdam, Spinoza wrote his Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being, which he never published in his lifetime, assuming with good reason that it might get suppressed. Two Dutch translations of it survive, discovered about 1810.[70]

In 1660 or 1661, Spinoza moved from Amsterdam to Rijnsburg (near Leiden), the center of Dutch Remonstrants known as the Collegiants.[11] In Rijnsburg, he began work on his Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy" as well as on his masterpiece, the Ethics. In 1663, he returned briefly to Amsterdam, where he finished and published Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy", the only work published in his lifetime under his own name, and then moved the same year to Voorburg.

In Voorburg, Spinoza continued work on his magnum opus, titled posthumously Ethics, and corresponded with scientists, philosophers, and theologians throughout Europe. He published in Latin, anonymously, and with false printer information Theological-Political Treatise (TTP) in 1670, in defense of secular and constitutional government, and in support of Johan de Witt, the Dutch Republic's grand pensionary, against the Stadtholder, the Prince of Orange.

Spinoza deliberately chose to write in Latin, which meant that his message was restricted to those learned few who knew the scholarly language. Dutch philosopher and physician, Adriaan Koerbagh attempted to publish a work in Dutch questioning the Trinity as a concept, asserted that Jesus was a human being, and that the scripture was not divinely inspired, was proposing ideas that also appear in Spinoza writings in Latin. Koerbagh's "A Flower Garden of All Sorts of Delights" in Dutch came to the attention of the authorities, who incarcerated him to be followed by exile, but he died while in prison. Spinoza did not wish to die a martyr to his ideas and exercised caution by publishing his 1670 TTP anonymously in Latin and refraining from publishing any further works. Unlike Koerbagh, Spinoza died at home in his own bed.[74]

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz visited Spinoza and claimed that Spinoza's life was in danger when supporters of the Prince of Orange murdered de Witt in 1672.[75] While the TTP was published anonymously, the work did not long remain so, and de Witt's enemies characterized it as "forged in Hell by a renegade Jew and the Devil, and issued with the knowledge of Jan de Witt". It was placed on the Catholic Church's Index of Prohibited Works in 1679.[76]

In 1670, Spinoza moved to The Hague, where he lived on a small pension from Jan de Witt and a small annuity from the brother of his dead friend, Simon de Vries.[77] He worked on the manuscript of what was later called Ethics, wrote an unfinished Hebrew grammar, began his Political Treatise (TP), left unfinished at his death, wrote two scientific essays ("On the Rainbow" and "On the Calculation of Chances"), and began a Dutch translation of the Bible (which he later destroyed).[77] Spinoza was offered the chair of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg. He refused it, perhaps because of the possibility that it might in some way curb his freedom of thought.[78]

Spinoza also corresponded with Peter Serrarius, a radical Protestant and millenarian merchant. Serrarius was a patron to Spinoza after Spinoza was expelled from the Jewish community. He acted as an intermediary for Spinoza's correspondence, sending and receiving letters of the philosopher to and from third parties. Spinoza and Serrarius maintained their relationship until Serrarius died in 1669.[79]

By the beginning of the 1660s, Spinoza's name became more widely known. The Secretary of the British Royal Society Henry Oldenburg paid him visits and became a correspondent with Spinoza for the rest of his life.[80] In 1676, Leibniz wanted to examine a manuscript copy of the Ethics and traveled to the Hague to meet Spinoza, conversing with him at great length.[81]

Lens-grinding and optics[edit]

Spinoza earned a modest living from lens-grinding and instrument making, yet he was involved in important optical investigations of the day while living in Voorburg, through correspondence and friendships with scientist Christiaan Huygens and mathematician Johannes Hudde, including debate over microscope design with Huygens, favoring small objectives[82] and collaborating on calculations for a prospective 40-foot (12 m) focal length telescope which would have been one of the largest in Europe at the time.[83] He was known for making not just lenses but also telescopes and microscopes.[84] The quality of Spinoza's lenses was much praised by Christiaan Huygens, among others.[85] In fact, his technique and instruments were so esteemed that Constantijn Huygens ground a "clear and bright" telescope lens with focal length of 42 feet (13 m) in 1687 from one of Spinoza's grinding dishes, ten years after his death.[86] He was said by anatomist Theodor Kerckring to have produced an "excellent" microscope, the quality of which was the foundation of Kerckring's anatomy claims.[87] During his time as a lens and instrument maker, he was also supported by small but regular donations from close friends.[59]

Death and rescue of his unpublished writings[edit]

Spinoza's health began to fail in 1676, and he died in The Hague on 21 February 1677 at age 44, attended by a physician friend, Georg Herman Schuller. Although he had been ill with some form of lung affliction, described as "ex phthisi [from consumption]", possibly complicated by silicosis brought on by grinding glass lenses,[88] he and everyone he lived with did not expect him to die that day, and he died without leaving a will.[89][90] There were assertions that he had repented his philosophical stances on his deathbed, but all credible evidence points to his dying unrepentant and in tranquility. Lutheran preacher Johannes Colerus wrote the first biography of Spinoza for the original reason of researching his final days.[91]

Spinoza was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) on the Spui four days after his death, on 25 February, inside the church, with six others in the same vault. At the time there was no memorial plaque for Spinoza. In the 18th century, the vault was emptied and the "remnants scattered over the earth of the churchyard." The memorial plaque visitors now see is outside, where some of his remains are part of the churchyard's soil.[92]

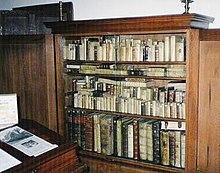

When he died, friends rescued his personal belongings and papers, most importantly his unpublished manuscripts. These were stored in a cabinet attached to his writing desk. His supporters swiftly took them away for safekeeping from seizure by those wishing to suppress his writings. They do not appear in the inventory of his possessions at death. Within a year of his death, his supporters translated his manuscripts written in Latin into Dutch, and subsequently into other vernacular languages. His works were banned by Dutch authorities and later the Roman Catholic Church.[93][94]

Writings[edit]

Spinoza published little in his lifetime and most of his formal writings were in Latin, which would have reached only a small number of readers. He actively told supporters not to translate his works, but following his death, his supporters published his works posthumously, in Latin and Dutch. A descriptive bibliography has been published that contextualizes all aspects of the publication history of Spinoza's writings from manuscript to print.[95]

The reaction to the anonymously published work, Theologico-Political Treatise (TTP)(1670), was extremely unfavorable. Spinoza abstained from publishing further, but his writings circulated among his supporters in manuscript form during his lifetime. Wary and independent, he wore a signet ring which he used to mark his letters and which was engraved with the word caute (Latin for "cautiously") underneath a rose, itself a symbol of secrecy.[96]

The Ethics and all other works, apart from the Descartes' Principles of Philosophy, which was published under his own name, and the Theologico-Political Treatise, published anonymously, appeared in print after his 1677 death. The Opera Posthuma was edited by his friends in secrecy to prevent confiscation and destruction of manuscripts. The Ethics contains many still-unresolved obscurities and is written with a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry and has been described as a "superbly cryptic masterwork".[97]

Correspondence[edit]

Few letters are extant for such an important intellectual figure and none before 1661. Practically all of them are of philosophical, technical nature, since "the political and ecclesiastical persecution of the time led the original editors of the Opera Posthuma his friends Lodewijk Meyer, Georg Hermann Schuller, and Johannes Bouwmeester—to delete personal matters and to disregard letters of a personal nature".[98] Spinoza engaged in correspondence from December 1664 to June 1665 with Willem van Blijenbergh, an amateur Calvinist theologian, who questioned Spinoza on the definition of evil. Later in 1665, Spinoza notified Oldenburg that he had started to work on a new book, the Theologico-Political Treatise, published in 1670. Leibniz disagreed harshly with Spinoza in his own manuscript "Refutation of Spinoza",[99] but he is also known to have met with Spinoza on at least one occasion[80][81] and his work bears some striking resemblances to some parts of Spinoza's philosophy, like in Monadology. Leibniz was concerned when his name was not redacted from a letter to Spinoza that was printed in the Opera Posthuma.[100]

In a letter, written in December 1675 and sent to Albert Burgh, who wanted to defend Catholicism, Spinoza clearly explained his view of both Catholicism and Islam. He stated that both religions are made "to deceive the people and to constrain the minds of men". He also states that Islam far surpasses Catholicism in doing so.[101][102] The Tractatus de Deo, Homine, ejusque Felicitate (Treatise on God, man and his happiness) was one of the last of Spinoza's works to be published, between 1851[103] and 1862.[104]

Philosophy[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Spinoza's philosophy is explicated in his two major publications originally written in Latin, the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP) (1670) and Ethics, published posthumously in Latin and Dutch. His incomplete Tractatus Politicus was also published posthumously.

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP)[edit]

Despite its being published in Latin rather than a vernacular language, this 1670 treatise published in Spinoza's lifetime caused a huge reaction, described as "one of the most significant events in European intellectual history."[105][106]

Ethics[edit]

The Ethics has been associated with that of Leibniz and René Descartes as part of the rationalist school of thought,[107] which includes the assumption that ideas correspond to reality perfectly, in the same way that mathematics is supposed to be an exact representation of the world. The writings of René Descartes have been described as "Spinoza's starting point".[97] Spinoza's first publication was his 1663 geometric exposition of proofs using Euclid's model with definitions and axioms of Descartes' Principles of Philosophy. Following Descartes, Spinoza aimed to understand truth through logical deductions from 'clear and distinct ideas', a process which always begins from the 'self-evident truths' of axioms.[108] However, his actual project does not end there: from his first work to his last one, there runs a thread of "attending to the highest good" (which also is the highest truth) and thereby achieving a state of peace and harmony, either in the metaphysical or political manner. In this light, the Principles of Philosophy might be viewed as an "exercise in geometric method and philosophy", paving the way for numerous concepts and conclusions that would define his philosophy (see Cogitata Metaphysica).[109]

Metaphysics[edit]

Spinoza's metaphysics consists of one thing, substance, and its modifications (modes). Early in The Ethics Spinoza argues that there is only one substance, which is absolutely infinite, self-caused, and eternal. He calls this substance "God", or "Nature". In fact, he takes these two terms to be synonymous (in the Latin the phrase he uses is "Deus sive Natura"). For Spinoza the whole of the natural universe consists of one substance, God, or, what is the same, Nature, and its modifications (modes).

It cannot be overemphasized how the rest of Spinoza's philosophy—his philosophy of mind, his epistemology, his psychology, his moral philosophy, his political philosophy, and his philosophy of religion—flows more or less directly from the metaphysical underpinnings in Part I of the Ethics.[110]

Substance, attributes, and modes[edit]

Spinoza sets forth a vision of Being, illuminated by his awareness of God. They may seem strange at first sight. To the question "What is?" he replies: "Substance, its attributes, and modes".

Following Maimonides, Spinoza defined substance as "that which is in itself and is conceived through itself", meaning that it can be understood without any reference to anything external.[112] Being conceptually independent also means that the same thing is ontologically independent, depending on nothing else for its existence and being the 'cause of itself' (causa sui).[112] A mode is something which cannot exist independently but rather must do so as part of something else on which it depends, including properties (for example colour), relations (such as size) and individual things.[113] Modes can be further divided into 'finite' and 'infinite' ones, with the latter being evident in every finite mode (he gives the examples of "motion" and "rest").[114] The traditional understanding of an attribute in philosophy is similar to Spinoza's modes, though he uses that word differently.[113] To him, an attribute is "that which the intellect perceives as constituting the essence of substance", and there are possibly an infinite number of them.[115] It is the essential nature which is "attributed" to reality by intellect.[116]

Spinoza defined God as "a substance consisting of infinite attributes, each of which expresses eternal and infinite essence", and since "no cause or reason" can prevent such a being from existing, it therefore must exist.[116] This is a form of the ontological argument, which is claimed to prove the existence of God, but Spinoza went further in stating that it showed that only God exists.[117] Accordingly, he stated that "Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can exist or be conceived without God".[117][118] This means that God is identical with the universe, an idea which he encapsulated in the phrase "Deus sive Natura" ('God or Nature'), which has been interpreted by some as atheism or pantheism.[119] Though there are many more of them, God can be known by humans either through the attribute of extension or the attribute of thought.[120] Thought and extension represent giving complete accounts of the world in mental or physical terms.[121] To this end, he says that "the mind and the body are one and the same thing, which is conceived now under the attribute of thought, now under the attribute of extension".[122]

After stating his proof for God's existence, Spinoza addresses who "God" is. Spinoza believed that God is "the sum of the natural and physical laws of the universe and certainly not an individual entity or creator".[123] Spinoza attempts to prove that God is just the substance of the universe by first stating that substances do not share attributes or essences and then demonstrating that God is a "substance" with an infinite number of attributes, thus the attributes possessed by any other substances must also be possessed by God. Therefore, God is just the sum of all the substances of the universe. God is the only substance in the universe, and everything is a part of God. This view was described by Charles Hartshorne as Classical Pantheism.[124]

Spinoza argues that "things could not have been produced by God in any other way or in any other order than is the case".[125] Therefore, concepts such as 'freedom' and 'chance' have little meaning.[119] This picture of Spinoza's determinism is illuminated in Ethics: "the infant believes that it is by free will that it seeks the breast; the angry boy believes that by free will he wishes vengeance; the timid man thinks it is with free will he seeks flight; the drunkard believes that by a free command of his mind he speaks the things which when sober he wishes he had left unsaid. … All believe that they speak by a free command of the mind, whilst, in truth, they have no power to restrain the impulse which they have to speak."[126] In his letter to G. H. Schuller (Letter 58), he wrote: "men are conscious of their desire and unaware of the causes by which [their desires] are determined."[127] He also held that knowledge of true causes of passive emotion can transform it into an active emotion, thus anticipating one of the key ideas of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis.[128]

According to Eric Schliesser, Spinoza was skeptical regarding the possibility of knowledge of nature and as a consequence at odds with scientists such as Galileo and Huygens.[129]

Causality[edit]

Although the principle of sufficient reason is commonly associated with Gottfried Leibniz, Spinoza employs it in a more systematic manner. In Spinoza's philosophical framework, questions concerning why a particular phenomenon exists are always answerable, and these answers are provided in terms of the relevant cause. Spinoza's approach involves first providing an account of a phenomenon, such as goodness or consciousness, to explain it, and then further explaining the phenomenon in terms of itself. For instance, he might argue that consciousness is the degree of power of a mental state.[130]

Spinoza has also been described as an "Epicurean materialist",[97] specifically in reference to his opposition to Cartesian mind-body dualism. This view was held by Epicureans before him, as they believed that atoms with their probabilistic paths were the only substance that existed fundamentally.[131][132] Spinoza, however, deviated significantly from Epicureans by adhering to strict determinism, much like the Stoics before him, in contrast to the Epicurean belief in the probabilistic path of atoms, which is more in line with contemporary thought on quantum mechanics.[131][133]

The emotions[edit]

One thing which seems, on the surface, to distinguish Spinoza's view of the emotions from both Descartes' and Hume's pictures of them is that he takes the emotions to be cognitive in some important respect. Jonathan Bennett claims that "Spinoza mainly saw emotions as caused by cognitions. [However] he did not say this clearly enough and sometimes lost sight of it entirely."[134] Spinoza provides several demonstrations which purport to show truths about how human emotions work. The picture presented is, according to Bennett, "unflattering, coloured as it is by universal egoism".[135]

Ethical philosophy[edit]

Spinoza's notion of blessedness figures centrally in his ethical philosophy. Spinoza writes that blessedness (or salvation or freedom), "consists, namely, in a constant and eternal love of God, or in God’s love for men.[136] Philosopher Jonathan Bennett interprets this as Spinoza wanting "'blessedness' to stand for the most elevated and desirable state one could possibly be in."[137] Understanding what is meant by "most elevated and desirable state" requires understanding Spinoza's notion of conatus (striving, but not necessarily with any teleological baggage)[citation needed] and that "perfection" refers not to (moral) value, but to completeness. Given that individuals are identified as mere modifications of the infinite Substance, it follows that no individual can ever be fully complete, i.e., perfect, or blessed. Absolute perfection, is, in Spinoza's thought, reserved solely for Substance. Nevertheless, modes can attain a lesser form of blessedness, namely, that of pure understanding of oneself as one really is, i.e., as a definite modification of Substance in a certain set of relationships with everything else in the universe. That this is what Spinoza has in mind can be seen at the end of the Ethics, in E5P24 and E5P25, where Spinoza makes two final key moves, unifying the metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical propositions he has developed over the course of the work. In E5P24, he links the understanding of particular things to the understanding of God, or Substance; in E5P25, the conatus of the mind is linked to the third kind of knowledge (Intuition). From here, it is a short step to the connection of Blessedness with the amor dei intellectualis ("intellectual love of God").[citation needed]

Tractatus Politicus (Political Treatise) (TP)[edit]

This unfinished treatise in Latin expounds Spinoza's ideas about forms of government. As with the Ethics, this work was published posthumously by his circle of supporters in Latin and in Dutch. The subtitle is "In quo demonstratur, quomodo Societas, ubi Imperium Monarchicum locum habet, sicut et ea, ubi Optimi imperant, debet institui, ne in Tyrannidem labatur, et ut Pax, Libertasque civium inviolata maneat." ("In which it is demonstrated how a society, may it be a monarchy or an aristocracy, can be best governed, so as not to fall into tyranny, and so that the peace and liberty of the citizens remain unviolated").

Although Spinoza’s political and theological thought was radical on many ways, he held traditional views on the place of women. In the TP, he writes briefly on the last page of the TP that women were “naturally” subordinate to men, stating bluntly his women are “by nature” not by “institutional practice” subordinate to men. Both his major biographers in English remark on his view of women. Biographer Steven Nadler is clearly disappointed by Spinoza's only statement on women. “It is unfortunate that the very last words we have by him, at the end of the extant chapters of the Political Treatise, are a short digression … on the unsuitability of women to hold political power.”[138] Likewise Jonathan I. Israel says that Spinoza's views are “hugely disappointing to the modern reader” and that most that can be said in his defense is that “in his age rampant tyrannizing over women was indeed universal.” He goes on to say, "one may legitimately wonder why did Spinoza, if he was to be consistent, not apply his highly sceptical and innovative, for his time uniquely subversive, de-legtimizing general principle likewise to men's tyrannizing over women."[139] One scholar has attempted to rationalize Spinoza’s views excluding women from full citizenship.[140] But the topic has not attracted major consideration in Spinoza studies.

Pantheism[edit]

Spinoza was considered to be an atheist because he used the word "God" [Deus] to signify a concept that was different from that of traditional Judeo–Christian monotheism. "Spinoza expressly denies personality and consciousness to God; he has neither intelligence, feeling, nor will; he does not act according to purpose, but everything follows necessarily from his nature, according to law...."[141] Thus, Spinoza's cool, indifferent God differs from the concept of an anthropomorphic, fatherly God who cares about humanity.[142]

In 1785, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi published a condemnation of Spinoza's pantheism, after Gotthold Lessing was thought to have confessed on his deathbed to being a "Spinozist", which was the equivalent in his time of being called an atheist. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because all Nature and God are said to be nothing but extended substance. This, for Jacobi, was the result of Enlightenment rationalism and it would finally end in absolute atheism. Moses Mendelssohn disagreed with Jacobi, saying that there is no actual difference between theism and pantheism. The issue became a major intellectual and religious concern for European civilization at the time.

The attraction of Spinoza's philosophy to late 18th-century Europeans was that it provided an alternative to materialism, atheism, and deism. Three of Spinoza's ideas strongly appealed to them:

- the unity of all that exists;

- the regularity of all that happens;

- the identity of spirit and nature.[143]

By 1879, Spinoza's pantheism was praised by many, but was considered by some to be alarming and dangerously inimical.[144]

Spinoza's "God or Nature" (Deus sive Natura) provided a living, natural God, in contrast to Isaac Newton's first cause argument and the dead mechanism of Julien Offray de La Mettrie's (1709–1751) work, Man a Machine (L'homme machine). Coleridge and Shelley saw in Spinoza's philosophy a religion of nature.[59] Novalis called him the "God-intoxicated man".[97][145] Spinoza inspired the poet Shelley to write his essay "The Necessity of Atheism".[97]

It is a widespread belief that Spinoza equated God with the material universe. He has therefore been called the "prophet"[146] and "prince"[147] and most eminent expounder of pantheism. More specifically, in a letter to Henry Oldenburg he states, "as to the view of certain people that I identify God with Nature (taken as a kind of mass or corporeal matter), they are quite mistaken".[148] For Spinoza, the universe (cosmos) is a mode under two attributes of Thought and Extension. God has infinitely many other attributes which are not present in the world.

According to German philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), when Spinoza wrote Deus sive Natura (Latin for 'God or Nature'), Spinoza meant God was natura naturans (nature doing what nature does; literally, 'nature naturing'), not natura naturata (nature already created; literally, 'nature natured'). Jaspers believed that Spinoza, in his philosophical system, did not mean to say that God and Nature are interchangeable terms, but rather that God's transcendence was attested by his infinitely many attributes, and that two attributes known by humans, namely Thought and Extension, signified God's immanence.[149] Even God under the attributes of thought and extension cannot be identified strictly with our world. That world is of course "divisible"; it has parts. But Spinoza said, "no attribute of a substance can be truly conceived from which it follows that the substance can be divided", meaning that one cannot conceive an attribute in a way that leads to division of substance. He also said, "a substance which is absolutely infinite is indivisible" (Ethics, Part I, Propositions 12 and 13).[150] Following this logic, our world should be considered as a mode under two attributes of thought and extension. Therefore, according to Jaspers, the pantheist formula "One and All" would apply to Spinoza only if the "One" preserves its transcendence and the "All" were not interpreted as the totality of finite things.[149]

Martial Guéroult (1891–1976) suggested the term panentheism, rather than pantheism to describe Spinoza's view of the relation between God and the world. The world is not God, but in a strong sense, "in" God. Not only do finite things have God as their cause; they cannot be conceived without God.[150] However, American panentheist philosopher Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000) insisted on the term Classical Pantheism to describe Spinoza's view.[124]

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spinoza's God is an "infinite intellect" (Ethics 2p11c) — all-knowing (2p3), and capable of loving both himself—and us, insofar as we are part of his perfection (5p35c). And if the mark of a personal being is that it is one towards which we can entertain personal attitudes, then we should note too that Spinoza recommends amor intellectualis dei (the intellectual love of God) as the supreme good for man (5p33). However, the matter is complex. Spinoza's God does not have free will (1p32c1), he does not have purposes or intentions (1 appendix), and Spinoza insists that "neither intellect nor will pertain to the nature of God" (1p17s1). Moreover, while we may love God, we need to remember that God is not a being who could ever love us back. "He who loves God cannot strive that God should love him in return", says Spinoza (5p19).[151]

Steven Nadler suggests that settling the question of Spinoza's atheism or pantheism depends on an analysis of attitudes. If pantheism is associated with religiosity, then Spinoza is not a pantheist, since Spinoza believes that the proper stance to take towards God is not one of reverence or religious awe, but instead one of objective study and reason, since taking the religious stance would leave one open to the possibility of error and superstition.[152]

Other philosophical connections[edit]

Many authors have discussed similarities between Spinoza's philosophy and Eastern philosophical traditions. Few decades after the philosopher's death, Pierre Bayle, in his famous Historical and Critical Dictionary (1697) pointed out a link between Spinoza's alleged atheism with "the theology of a Chinese sect", supposedly called "Foe Kiao",[153] of which had learned thanks to the testimonies of the Jesuit missions in Eastern Asia. A century later, Kant also established a parallel between the philosophy of Spinoza and the think of Laozi (a "monstrous system" in his words), grouping both under the name of pantheists, criticizing what he described as mystical tendencies in them.[154]

The 19th-century German Sanskritist Theodor Goldstücker was one of the early figures to notice the similarities between Spinoza's religious conceptions and the Vedanta tradition of India, writing that Spinoza's thought was "... so exact a representation of the ideas of the Vedanta, that we might have suspected its founder to have borrowed the fundamental principles of his system from the Hindus, did his biography not satisfy us that he was wholly unacquainted with their doctrines..."[155][156] Max Müller also noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and the system of Spinoza, equating the Brahman in Vedanta to Spinoza's 'Substantia.'[157]

Legacy[edit]

Spinoza's ideas have had a major impact on intellectual debates from the seventeenth century to the current era. How Spinoza is viewed has gone from the atheistic author of treatises that undermine Judaism and organized religion, to a cultural hero, the first secular Jew.[158] One writer contends that what draws readers to Spinoza today and "makes him perhaps the most beloved philosopher since Socrates, is his confident equanimity". He is not a despairing nihilist, but rather Spinoza says that "blessedness is nothing else but the contentment of spirit, which arises from the intuitive knowledge of God."[159] One of his biographers, Jonathan I. Israel, argues that "No leading figure of the post-1750 later Enlightenment, for example, or the nineteenth century, was engaged with the philosophy of Descartes, Hobbes, Bayle, Locke, or Leibniz, to the degree leading figures such as Lessing, Goethe, Kant, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling, Heine, George Eliot, and Nietzsche, remained preoccupied throughout their creative lives with Spinoza."[160] Hegel (1770-1831) asserts that "The fact is that Spinoza is made a testing-point in modern philosophy, so that it may really be said: You are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all."[161]

His expulsion from the Portuguese synagogue in 1656 has stirred debate over the years on whether he is the "first modern Jew". Spinoza influenced discussions of the so-called Jewish question, the examination of the idea of Judaism and the modern, secular Jew. Moses Mendelsohn, Lessing, Heine, and Kant, as well as subsequent thinkers, including Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud were influenced by Spinoza.[162] The changing conception of Spinoza as "the First Modern Jew" has been explicitly explored by various authors.[163][164][165] His expulsion has been revisited in the 21st century, with Jewish writers such Berthold Auerbach; Salomon Rubin, who translated Spinoza's Ethics into Hebrew and saw Spinoza as a new Maimonides, penning "a new guide to the perplexed"; Zionist Yosef Klausner, and fiction-writer Isaac Bashevis Singer shaping his image.[165]

In 1886, the young George Santayana published "The Ethical Doctrine of Spinoza", in The Harvard Monthly.[166] Much later, he wrote an introduction to Spinoza's Ethics and "De Intellectus Emendatione".[167] In 1932, Santayana was invited to present an essay (published as "Ultimate Religion")[168] at a meeting at The Hague celebrating the tricentennial of Spinoza's birth. In Santayana's autobiography, he characterized Spinoza as his "master and model" in understanding the naturalistic basis of morality.[169]

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein evoked Spinoza with the title (suggested to him by G. E. Moore) of the English translation of his first definitive philosophical work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, an allusion to Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Elsewhere, Wittgenstein deliberately borrowed the expression sub specie aeternitatis from Spinoza (Notebooks, 1914–16, p. 83). The structure of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus does have some structural affinities with Spinoza's Ethics (though, admittedly, not with the Spinoza's Tractatus) in erecting complex philosophical arguments upon basic logical propositions and principles. In propositions 6.4311 and 6.45 he alludes to a Spinozian understanding of eternity and interpretation of the religious concept of eternal life, contending, "If by eternity is understood not eternal temporal duration, but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present." (6.4311) "The contemplation of the world sub specie aeterni is its contemplation as a limited whole." (6.45)

Spinoza's philosophy played an important role in the development of post-war French philosophy. Many of these philosophers "used Spinoza to erect a bulwark against the nominally irrationalist tendencies of phenomenology", which was associated with the dominance of Hegel, Martin Heidegger, and Edmund Husserl in France at that time.[170] Louis Althusser, as well as his colleagues such as Étienne Balibar, saw in Spinoza a philosophy which could lead Marxism out of what they considered to be flaws in its original formulation, particularly its reliance upon Hegel's conception of the dialectic, as well as Spinoza's concept of immanent causality. Antonio Negri, in exile in France for much of this period, also wrote a number of books on Spinoza, most notably The Savage Anomaly (1981) in his own reconfiguration of Italian Autonomia Operaia. Other notable French scholars of Spinoza in this period included Alexandre Matheron, Martial Gueroult, André Tosel, and Pierre Macherey, the last of whom published a widely read and influential five-volume commentary on Spinoza's Ethics, which has been described as "a monument of Spinoza commentary".[171] His philosophical accomplishments and moral character prompted Gilles Deleuze in his doctoral thesis (1968) to name him "the prince of philosophers".[172][173] Deleuze's interpretation of Spinoza's philosophy was highly influential among French philosophers, especially in restoring to prominence the political dimension of Spinoza's thought.[174] Deleuze published two books on Spinoza and gave numerous lectures on Spinoza in his capacity as a professor at the University of Paris VIII. His own work was deeply influenced by Spinoza's philosophy, particularly the concepts of immanence and univocity. Marilena de Souza Chaui described Deleuze's Expressionism in Philosophy (1968) as a "revolutionary work for its discovery of expression as a central concept in Spinoza's philosophy."[174][clarification needed]

Albert Einstein named Spinoza as the philosopher who exerted the most influence on his world view (Weltanschauung). Spinoza equated God (infinite substance) with Nature, consistent with Einstein's belief in an impersonal deity. In 1929, Einstein was asked in a telegram by Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein whether he believed in God. Einstein responded by telegram: "I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings."[175][176] Einstein wrote the preface to a biography of Spinoza, published in 1946.[177]

Leo Strauss dedicated his first book, Spinoza's Critique of Religion, to an examination of his ideas. Strauss identified Spinoza as part of the tradition of Enlightenment rationalism that eventually produced Modernity. Moreover, he identifies Spinoza and his works as the beginning of Jewish Modernity.[97] More recently Jonathan Israel argued that, from 1650 to 1750, Spinoza was "the chief challenger of the fundamentals of revealed religion, received ideas, tradition, morality, and what was everywhere regarded, in absolutist and non-absolutist states alike, as divinely constituted political authority."[178]

Spinoza is an important historical figure in the Netherlands, where his portrait was featured prominently on the Dutch 1000-guilder banknote, legal tender until the euro was introduced in 2002. The highest and most prestigious scientific award of the Netherlands is named the Spinozaprijs (Spinoza prize). Spinoza was included in a 50 theme canon that attempts to summarise the history of the Netherlands.[179] In 2014 a copy of Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was presented to the Chair of the Dutch Parliament, and shares a shelf with the Bible and the Quran.[180]

Modern era[edit]

Reconsideration of Spinoza's expulsion[edit]

There has been a renewed debate in modern times about Spinoza's excommunication among Israeli politicians, rabbis and Jewish press, with many calling for the cherem to be reversed.[181] A conference was organized at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York entitled "From Heretic to Hero: A Symposium on the Impact of Baruch Spinoza on the 350th Anniversary of His Excommunication, 1656-2006". Presenters included Steven Nadler, Jonathan I. Israel, Steven B. Smith, and Daniel B. Schwartz.[182] There have been calls for Spinoza's cherem to be rescinded, but it can only be done by the congregation that issued it, and the chief rabbi of that community,[d] Haham Pinchas Toledano, declined to do so, citing Spinoza's "preposterous ideas, where he was tearing apart the very fundamentals of our religion",[183] the Amsterdam Jewish community organised a symposium in December 2015 to discuss lifting the cherem, inviting scholars from around the world to form an advisory committee at the meeting. However, the rabbi of the congregation ruled that it should hold, on the basis that he had no greater wisdom than his predecessors, and that Spinoza's views had not become less problematic over time.[181]

Memory and memorials[edit]

- Spinoza Lyceum, a high school in Amsterdam South was named after Spinoza. There is also a 3 metre tall marble statute of him on the grounds of the school carved by Hildo Krop.[184]

- The Spinoza Havurah (a Humanistic Jewish community) was named in Spinoza's honor.[185]

- The Spinoza Foundation Monument has a statute of Spinoza located in front of the Amsterdam City Hall (at Zwanenburgwal) [186] It was created by Dutch sculptor Nicolas Dings and was erected in 2008.[187][188]

Depictions and influence in literature[edit]

Spinoza's life and work have been subject of interest for several writers. For example, this influence was considerably early in German literature, where Goethe makes a glowing mention of the philosopher in his memoirs, highlighting a positive influence by the Ethics in his personal life.[189] The same thing happened in the case of his compatriot, the poet Heine, who is also lavish in praise for Spinoza on his On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany (1834).[190]

In the following century, the Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges famously wrote two sonnets in his honor ("Spinoza" in El otro, el mismo, 1964; and "Baruch Spinoza" in La moneda de hierro, 1976), and several direct references to Spinoza's philosophy can be found in this writer's work.[191] Also in Argentina and previously to Borges, the Ukrainian-born Jewish intellectual Alberto Gerchunoff wrote a novella about philosopher's early sentimental life, Los amores de Baruj [sic] Spinoza (lit. "The loves of Baruj Spinoza", 1932), recreating a supposed affair or romantic interest with Clara Maria van den Enden, daughter of his latin teacher and philosophical preceptor, Franciscus.[192]

That is not the only fiction work where the philosopher appears as the main character. In 1837 the German writer Berthold Auerbach dedicated to him the first novel in his series on Jewish history, translated into English in 1882 (Spinoza: a Novel).[193] Some other novels of biographical nature have appeared more recently, as The Spinoza Problem (2012; a parallel story between the philosopher's formative years, and the fascination that his work had on the Nazi leader Alfred Rosenberg) by psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom, or O Segredo de Espinosa (lit. "The Secret of Spinoza", 2023) by Portuguese journalist José Rodrigues dos Santos. Spinoza also appear in the first novel of the Argentinian activist Andres Spokoiny, El impío (lit. "The Impious", 2021), about the marrano phicicyst and philosopher Juan de Prado, a key influence in his biography. [194]

Not directly his person, but his influence or legacy are themes present both in "The Spinoza of Market Street", a short story by the Polish-born Jewish-American Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer (originally written in yiddish in 1961), and also in the recent novel by Mexican Ezra Béjar Un Baruch para Spinoza (lit. "A Baruch for Spinoza", 2023).[195]

In another sense, Spinoza's philosophy is an important part of the series of satirical punk post-apocalyptic fiction novels by the French writer Jean-Bernard Pouy, begun with Spinoza encule Hegel (lit. "Spinoza fucks Hegel", 1983), where the protagonist take the nickname of "Spinoza" or "Spino" and projects a violent application of his thinking in a lawless world. The series continued with two more novels, subsequently issued in 1998 and 2006.

Finally, the British art critic John Berger published some prose poems and drawings under the title of Bento's Sketchbook (2011), inspired by the Philosopher's work (from which he takes literal quotes), and in the anecdote about the existence of a drawing notebook among his belongings that disappeared after his death.

Works[edit]

Original Editions[edit]

- c. 1660. Korte Verhandeling van God, de mensch en deszelvs welstand (unpublished until XIXth Century; A Short Treatise on God, Man and His Well-Being; translated by A. Wolf. London, Adam and Charles Black Eds., 1910).

- 1662. Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione (On the Improvement of the Understanding) (unfinished).

- 1663. Principia philosophiae cartesianae (The Principles of Cartesian Philosophy, also contains Metaphysical Thoughts/Cogitata Metaphisica; translated by Samuel Shirley, with an Introduction and Notes by Steven Barbone and Lee Rice, Indianapolis, 1998).

- 1670. Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (A Theologico-Political Treatise), TTP, published anonymously in his lifetime with a false place of publication.

- 1675–76. Tractatus Politicus (Political Treatise), TP (unfinished at his death), published posthumously.

- 1677. Ethica Ordine Geometrico Demonstrata (The Ethics, finished 1674, but published posthumously, title added posthumously).

- 1677. Compendium grammatices linguae hebraeae (Hebrew Grammar, unfinished; translated with introduction by M. J. Bloom, London, 1963).[196]

- 1677. Epistolae (The Letters, translated by Samuel Shirley, with an Introduction and Notes by S. Barbone, L. Rice and J. Adler, Indianapolis, 1995).

- Last four were originally collected and published by Spinoza's friends briefly later his death, in: B. d. S. Opera Posthuma, Quorum series post Praefationem exhibetur. (Amsterdam: Jan Rieuwertsz, 1677; both publisher and place were purposely omitted). Simultaneously, Rieuwertsz also published a Dutch translation by Jan Hendriksz Glazemaker (who some years later translated the TTP): De Nagelate Schriften van B. d. S., without the Hebrew Grammar.

Contemporary Editions[edit]

- Morgan, Michael L. (ed.), 2002. Spinoza: Complete Works, with the Translation of Samuel Shirley, Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-620-5.

- Edwin Curley (ed.), 1985, 2016. The Collected Works of Spinoza (two volumes), Princeton: Princeton University Press.(Excludes the Compendium grammatices linguae hebraeae).

- Spruit, Leen and Pina Totaro, 2011. The Vatican Manuscript of Spinoza's Ethica, Leiden: Brill. This is the only known surviving manuscript of Spinoza's Ethics, discovered in the Vatican archive and published in a bilingual Latin-English edition.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Spinoza has also been interpreted as a defender of the coherence theory of truth.[3]

- ^ /bəˈruːk spɪˈnoʊzə/;[12] Dutch: [baːˈrux spɪˈnoːzaː]; Portuguese: [ðɨ ʃpiˈnɔzɐ]; Hebrew: ברוך שפינוזה. His boyhood and early adult business name was "Bento", and his synagogue name was "Baruch", the Hebrew translation of "Bento", which means "blessed".[13] As a correspondent, he primarily signed his name as Benedictus.[14]

- ^ Steven Nadler speculates that Spinoza Latinized his name when he started to audit classes at the University of Leiden in 1659.[55]

- ^ Portugees-Israëlietische Gemeente te Amsterdam (Portuguese-Israelite commune of Amsterdam)

Citations[edit]

- ^ Garber 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Newlands 2017, p. 64.

- ^ Young, James O. (26 June 2018). "The Coherence Theory of Truth". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ David, Marian (28 May 2015). "The Correspondence Theory of Truth". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Koistinen 2018, p. 288.

- ^ Kreines 2015, p. 25.

- ^ LeBuffe, Michael (26 May 2020). "Spinoza's Psychological Theory". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Yovel 1989b, p. 3.

- ^ a b Nadler 1999, p. 45.

- ^ Nadler 1999, p. 119.

- ^ a b Adler 2014, p. 27.

- ^ "Spinoza". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Nadler 1999, p. 42.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 353–54.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. xiii.

- ^ Dutton, Blake D. "Benedict De Spinoza (1632–1677)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 322.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 352.

- ^ Simkins 2014.

- ^ Carlisle 2021, p. 10.

- ^ Smith 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Goldstein 2006, p. i.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, p. 115.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 85.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 134.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 88.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 299.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 124.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, p. 158.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 144.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 140.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, p. 140-41.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. 38.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, p. 183.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 117.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, p. 185.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 145-46.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 159.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 160.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 161.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 90.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. 84.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 148–49.

- ^ Nadler 1999, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Nadler 2018, pp. 72–75.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Nadler 2018, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 206.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 204–05.

- ^ a b Israel 2023, pp. 205–06.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Nadler 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 220–22.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 222.

- ^ Nadler 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 189.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Gottlieb, Anthony. "God Exists, Philosophically". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Nadler 2001, pp. 17–22.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 74.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Touber 2018, p. 45.

- ^ Nadler 2001, pp. 2–7.

- ^ Smith 2003, p. xx.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Scruton 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Kramer, Howard (14 August 2014). "HOME & GRAVESITE OF BARUCH SPINOZA". The Complete Pilgrim - Religious Travel Sites. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Nadler 2011, p. 167.

- ^ Kirsch, Adam, "The Reticent Radical: Baruch Spinoza's quiet revolution". The New Yorker, February 12 & 19, 2024, 89-92

- ^ Kirsch, "The Reticent Radical", p.92

- ^ "he [Spinoza] told me [Leibniz] he had a strong desire, on the day of the massacre of Mess. De Witt, to sally forth at night, and put up somewhere, near the place of the massacre, a paper with the words Ultimi barbarorum [ultimate barbarians]. But his host had shut the house to prevent his going out, for he would have run the risk of being torn to pieces." (A Refutation Recently Discovered of Spinoza by Leibnitz, "Remarks on the Unpublished Refutation of Spinoza by Leibnitz", Edinburg: Thomas Constable and Company, 1855. p. 70.

- ^ Nadler 2011, p. 239.

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Chauí 2001, pp. 30–31: "A commentary on Descartes' work, Principles of Cartesian Philosophy, only work published under his own name, brought him on an invitation to teach philosophy at the University of Heidelberg. Spinoza, however, refused, thinking that it might demand the renunciation of his freedom of thought, for the invite stipulated that all care should be taken to 'not insult the principles of the established religion'."

- ^ Popkin, Richard H., "Benedict de Spinoza" in The Columbia History of Western Philosophy (Columbia University Press, 1999), p. 381.

- ^ a b Lucas 1960.

- ^ a b Stewart 2006, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres complètes, Letter No. 1638, 11 May 1668

- ^ Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres complètes, letter to his brother 23 September 1667

- ^ Nadler 1999, p. 215.

- ^ Nadler 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres complètes, vol. XXII, p. 732, footnote

- ^ Theodore Kerckring, "Spicilegium Anatomicum" Observatio XCIII (1670)

- ^ Gullan-Whur 1998, pp. 317–18.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 1150–1151.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. 406.

- ^ Israel 2023, p. 1155.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 1158.

- ^ Jonathan Israel, "The Banning of Spinoza's Works in the Dutch Republic (1670–1678)", in: Wiep van Bunge and Wim Klever (eds.) Disguised and Overt Spinozism around 1700 (Leiden, 1996), pp. 3–14 (online Archived 28 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Totaro 2015, pp. 321–22.

- ^ Ven, Jeroen van de. Printing Spinoza: A Descriptive Bibliography of the Works Published in the Seventeenth Century. Leiden; Brill, 2022.

- ^ Stewart 2006, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom, Harold (16 June 2006). "Deciphering Spinoza, the Great Original – Book review of Betraying Spinoza. The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity by Rebecca Goldstein". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ Morgan, Michael L. (2002). Spinoza: Complete Works, with the Translation of Samuel Shirley. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. p. 755. ISBN 978-0-87220-620-5.

- ^ see Refutation of Spinoza

- ^ Buruma 2024, pp. 166–67.

- ^ "Spinoza on Islam". 13 February 2012.

- ^ Spinoza, Baruch (2003). Correspondence of Spinoza. Translated by A. Wolf. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 354.

- ^ Coyle, Patrick A. (1938). Some aspects of the philosophy of Spinoza and his ontological proof of the existence of God (PDF). University of Western Ontario, CA. p. 2. OCLC 1067012129. Retrieved 9 June 2021 – via University of Windsor, Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ Soley 1880.

- ^ Nadler 2011, p. xi.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 776.

- ^ Montanarelli, Lisa. "Spinoza stymies 'God's attorney' / Stewart argues the secular world was at stake in Leibniz face off". SFGate. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Scruton 2002, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Morgan, Michael L. (2002). Spinoza: Complete Works, with the Translation of Samuel Shirley. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-87220-620-5.

- ^ Della Rocca 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Jaspers 1974, p. 9.

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 41

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 42

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 43.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 44.

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 45.

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 38

- ^ Lin, Martin (2007). "Spinoza's Arguments for the Existence of God". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 75 (2): 269–297. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2007.00076.x.

- ^ a b Scruton 2002, p. 51.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Cannon, J. A. (2009, May 17). World in time of upheaval: Sources of enlightenment. Deseret News.

- ^ a b Charles Hartshorne and William Reese, "Philosophers Speak of God", Humanity Books, 1953 ch. 4

- ^ Baruch Spinoza. Ethics, in Spinoza: Complete Works, trans. by Samuel Shirley and ed. by Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2002), see Part I, Proposition 33.

- ^ Curley 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Ethics, Pt. I, Prop. XXXVI, Appendix: "[M]en think themselves free inasmuch as they are conscious of their volitions and desires, and never even dream, in their ignorance, of the causes which have disposed of them so to wish and desire."

- ^ Scruton 2002, p. 86.

- ^ ""Spinoza and the Philosophy of Science: Mathematics, Motion, and Being"". PhilSci-Archive. 9 July 2012.

- ^ Della Rocca 2008, p. 30.

- ^ a b Konstan, David (8 July 2022). "Epicurus". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Curley 1996, p. 118.

- ^ "Baruch Spinoza, "Human Beings are Determined"". Lander.edu. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Bennett 1984, p. 276.

- ^ Bennett 1984, p. 277.

- ^ Spinoza, Benedictus de (1996). Ethics. Penguin Books. p. 176. ISBN 9780140435719.

- ^ Bennett 1984, p. 371.

- ^ Nadler 2018, p. 495.

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 895–96.

- ^ Matheron, Alexandre, “Femmes et serviteurs dans lad démocratie spinoziste.” Revue philosophique de la la France et de l’étranger 2 (1977) 181-200

- ^ Frank Thilly, A History of Philosophy, § 47, Holt & Co., New York, 1914

- ^ "I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings." These words were spoken by Albert Einstein, upon being asked if he believed in God by Rabbi Herbert Goldstein of the Institutional Synagogue, New York, April 24, 1921, published in the New York Times, April 25, 1929; from Einstein: The Life and Times Ronald W. Clark, New York: World Publishing Co., 1971, p. 413; also cited as a telegram to a Jewish newspaper, 1929, Einstein Archive 33–272, from Alice Calaprice, ed., The Expanded Quotable Einstein, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

- ^ Lange, Frederick Albert (1880). History of Materialism and Criticism of its Present Importance, Vol. II. Boston: Houghton, Osgood, & Co. p. 147. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ "The Pantheism of Spinoza Dr. Smith regarded as the most dangerous enemy of Christianity, and as he announced his conviction that it had gained the control of the schools, press and pulpit of the Old World [Europe], and was rapidly gaining the same control of the New [United States], his alarm and indignation sometimes rose to the eloquence of genuine passion." Memorial of the Rev. Henry Smith, D.D., LL D., Professor of Sacred Rhetoric and Pastoral Theology in Lane Theological Seminary, Consisting of Addresses on Occasion of the Anniversary of the Seminary, 8 May 1879, Together with Commemorative Resolutions, p. 26.

- ^ Hutchison, Percy (20 November 1932). "Spinoza, "God-Intoxicated Man"; Three Books Which Mark the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Philosopher's Birth". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ Picton, J. Allanson, "Pantheism: Its Story and Significance", 1905.

- ^ Fraser, Alexander Campbell "Philosophy of Theism", William Blackwood and Sons, 1895, p. 163.

- ^ Correspondence of Benedict de Spinoza, Wilder Publications (26 March 2009), ISBN 978-1-60459-156-9, letter 73.

- ^ a b Jaspers 1974, pp. 14, 95

- ^ a b Genevieve Lloyd, Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Spinoza and The Ethics (Routledge Philosophy Guidebooks), Routledge; 1 edition (2 October 1996), ISBN 978-0-415-10782-2, p. 40

- ^ Mander, William (17 August 2023). "Pantheism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Nadler, Steven (8 November 2023). "Baruch Spinoza". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Pierre Bayle. Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, vol. 13 (in French). Libraire Desoer, Paris, 1820, p. 416

- ^ Immanuel Kant. "The end of all things", in: Religion and Rational Theology. Transl. and edited by Allen W. Wood and George Di Giovanni. Cambridge University Press, p.228

- ^ Literary Remains of the Late Professor Theodore Goldstucker, W. H. Allen, 1879. p. 32.

- ^ The Westminster Review 1862, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Three Lectures on the Vedanta Philosophy. F. Max Muller. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. p. 123

- ^ "Ralph Dumain: "The Autodidact Project": "Spinoza, the First Secular Jew?" by Yirmiyahu Yovel".

- ^ Kirsch, "The Reticent Radical", p.92

- ^ Israel 2023, pp. 1205.

- ^ Hegel Society of America. Meeting (2003). Duquette, David A. (ed.). Hegel's History of Philosophy: New Interpretations. SUNY Series in Hegelian Studies. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791455432. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Smith 1997, p. 168-69.

- ^ Yovel, Yirmiyahu. "Spinoza, the First Secular Jew?" Tikkun, vol. 5, no.1, pp. 40-42, 94-96.

- ^ Goetschel, Willi, Spinoza's Modernity: Mendelssohn, Lessing, and Heine. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 2004

- ^ a b Schwartz, Daniel B. The First Modern Jew: Spinoza and the History of an Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2012

- ^ George Santayana, "The Ethical Doctrine of Spinoza", The Harvard Monthly, 2 (June 1886: 144–52).

- ^ George Santayana, "Introduction", in Spinoza's Ethics and "De intellectus emendatione"(London: Dent, 1910, vii–xxii)

- ^ George Santayana, "Ultimate Religion", in Obiter Scripta, eds. Justus Buchler and Benjamin Schwartz (New York and London: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936) 280–97.

- ^ George Santayana, Persons and Places (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1986), pp. 233–36.

- ^ Peden, Knox (2014). Spinoza contra phenomenology : French rationalism from Cavaillès to Deleuze. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9136-6. OCLC 880877889.

- ^ Baugh, Bruce (28 March 2015). "Spinoza Contra Phenomenology: French Rationalism from Cavaillès to Deleuze". Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Deleuze, 1968.

- ^ Quoted in the translator's preface of Deleuze's Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza (1990).

- ^ a b Rocha, Mauricio (2021), "Spinozist Moments in Deleuze: Materialism as Immanence", Materialism and Politics, Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, pp. 73–90, doi:10.37050/ci-20_04, S2CID 234131869, retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Einstein believes in "Spinoza's God"; Scientist Defines His Faith in Reply, to Cablegram From Rabbi Here. Sees a Divine Order But Says Its Ruler Is Not Concerned "Wit [sic] Fates and Actions of Human Beings."". The New York Times. 25 April 1929. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "Einstein's Third Paradise, by Gerald Holton". Aip.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Kaiser, Rudolf, Spinoza: Portrait of a Spiritual Hero. New York: Philosophical Library 1946

- ^ Israel 2001, p. 159.

- ^ "Entoen.nu". Entoen.nu. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Van der Ham biedt Verbeet Spinoza aan". RTL Nieuws. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ a b Rutledge, David (3 October 2020). "The Jewish philosopher Spinoza was one of the great Enlightenment thinkers. So why was he 'cancelled'?". ABC News. ABC Radio National (The Philosopher's Zone). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Schwartz. The First Modern Jew: Spinoza and the History of an Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2012, xi

- ^ Rocker, Simon (28 August 2014). "Why Baruch Spinoza is still excommunicated". The Jewish Chronicle Online.

- ^ "Mo 50 – Statue Spinoza – Amsterdam" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ SpinozaHavurah.org Archived 1 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed Nov. 202, 2022)

- ^ "Statute of Spinoza unveiled in Amsterdam centre" Simply Amsterdam (Nov. 25, 2008) Archived 21 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed Nov. 20, 2022)

- ^ "Who stands proud on a pedestal in Amsterdam" Unclogged in Amsterdam : An American Expat plumbs Holland (Aug. 22, 2020) Archived 21 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed Nov. 20, 2022)

- ^ "Spinoza Monument" CitySeeker.com Archived 21 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed Nov. 20, 2022)

- ^ Johan W. von Goethe. Autobiography, vol. 2. Transl. by John Oxenford. The Anthological Society. London-Chicago, 1901, Chapters 14-16, p.178-248

- ^ Heinrich Heine. On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany. Edited by Paul L. Rose. James Cook University of North Queensland, 1982, p. 56-57

- ^ Marcelo Abadi: "Spinoza in Borges' looking-glass". Borges Studies Online. J. L. Borges Center for Studies & Documentation. Internet: 14/04/01

- ^ Diego Sztulwark: "Spinoza y la cultura judía argentina" (in Spanish). El Cohete a la Luna, 2/6/2022

- ^ See complete text on Wikisource.

- ^ El Impío de Andrés Spokoiny (In Spanish). 05/27/2022.

- ^ Baruch Spinoza, un pensador que cimbró su tiempo (in Spanish). 8/14/2022

- ^ See G. Licata, "Spinoza e la cognitio universalis dell'ebraico. Demistificazione e speculazione grammaticale nel Compendio di grammatica ebraica", Giornale di Metafisica, 3 (2009), pp. 625–61.

Sources[edit]

- Books

- Adler, Jacob (2014). "Mortality of the soul from Alexander of Aphrodisias to Spinoza". In Nadler, Steven (ed.). Spinoza and Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–35. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139795395.002. ISBN 978-1-139-79539-5 – via Cambridge Core.

- Bennett, Jonathan (1984). A Study of Spinoza's Ethics. Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 0-915145-83-9. OCLC 1036958076.

- Buruma, Ian (2024). Spinoza: Freedom's Messiah. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30-024892-0.

- Carlisle, Clare (2021). Spinoza's Religion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17659-8.

- Chauí, Marilena (2001) [1995]. Espinosa: uma filosofia da liberdade. São Paulo: Editora Moderna.

- Curley, Edwin, ed. (1985). The Collected Works of Spinoza, Volume 1. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07222-7.

- Curley, Edwin, ed. (1996). Ethics. Penguin classics (1st ed.). London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-043571-9.

- Della Rocca, Michael (2008). Spinoza. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-528330-4.

- Koistinen, Olli (2018). "Spinoza on Mind". In Della Rocca, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Spinoza. Cambridge: Oxford University Press. pp. 273–294. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195335828.013.004. ISBN 978-0-195-33582-8.

- Gullan-Whur, Margaret (1998). Within Reason: A Life of Spinoza. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-05046-3.

- Israel, Jonathan (2023). Spinoza, Life and Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-885748-8.

- Israel, Jonathan (2001). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925456-9.