Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2014 November 14

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < November 13 | << Oct | November | Dec >> | November 15 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

November 14[edit]

All the different dimensions[edit]

Do I understand correctly that we, you and I (and everything) are present in all the dimensions at once? Sometimes people talk about something coming from another dimension as though it came from a different universe whereas I have always thought of dimensions as being something we have a position in. Thus instead of coming from a different dimension, some object or creature might come from a different position within that dimension to our position in that dimension and thus become observable to us? Is that wrong? --78.148.109.47 (talk) 05:21, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, yes, no. Plasmic Physics (talk) 05:48, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Is it so simple? Is time a dimension? Am I currently "present" at all points in time? Block universe and multiverse might be of interest when thinking about this question. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:51, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, time is normally considered a dimension, but behaves differently than the other dimensions, for reasons that cannot be explained in current physics. When something is said to have "come from a different dimension", it usually means that it is said to have come from a higher-order spatial dimension, presumably a spatial dimension with full extension that we cannot observe. The universe that we can observe consists of three spatial dimensions and time. Some Theories of Everything have various additional dimensions that are "rolled up". So if something really has come from a dimension beyond the three that we can observe, it is a matter of terminology or philosophy whether it comes from another universe or an aspect of this universe that we cannot observe. Robert McClenon (talk) 17:07, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Is it so simple? Is time a dimension? Am I currently "present" at all points in time? Block universe and multiverse might be of interest when thinking about this question. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:51, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, yes, no to your questions also. Plasmic Physics (talk) 03:55, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Yes, yes, no" to my questions? I wasn't asking questions. Does that mean yes, yes, and no to the OP's questions? Robert McClenon (talk) 22:32, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- No, the indent level indicates that I was responding to Mantis. Plasmic Physics (talk) 00:23, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- See Flatland.—Wavelength (talk) 17:24, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Be aware that Flatland is primarily a social satire rather than a scientific textbook, although I can second Wavelength's recommendation. Tevildo (talk) 19:50, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yeah Flatland's coverage of 2D life is exceedingly patchy and inconsistent. I don't know why people still recommend it for that reason. A VASTLY better book about a 2D world is "Planiverse" - which is modern, has lots of clever insights and an actual, interesting plot. SteveBaker (talk) 21:19, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Be aware that Flatland is primarily a social satire rather than a scientific textbook, although I can second Wavelength's recommendation. Tevildo (talk) 19:50, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- I wonder if you are actually talking about quantum states, as in the Schrödinger's cat, for example an electron exist in several quantum states simultaneously, so is every particles in the universe, so we would be into an Multiverse, and to my knowledge it's not possible to go from one "universe" to another, a bit like it's impossible to have a coin with a single face, both sides exist or none exist. Joc (talk) 21:03, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- In theories with small compactified extra dimensions, ordinary matter spans the entirety of the extra dimensions—it's "fat" in the extra dimensions, if you like. Matter at much higher energies can be "thin" and have a position in the extra dimensions, but it will always be visible to ordinary matter because the ordinary matter is everywhere. In braneworld models, ordinary matter is stuck to a lower-dimensional surface (the brane), so it does have a position in the higher-dimensional space. However, I don't think there's any way for higher-dimensional objects not attached to a brane to exist in those models. There's nothing out there except gravity. The idea, common in fantasy/SF stories, that you could see a slice through a higher-dimensional object as it passed through our lower-dimensional world is not consistent with any physical theory I've heard of. -- BenRG (talk) 23:02, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Designing experiment to compare thermal clothing performance[edit]

I was thinking of designing and performing an experiment at home to determine the performances of different items of thermal clothing and I was wondering if someone might care to contribute to ensure that I don't miss any opportunities and flaw my experiment.

I thought I could simulate the body with a hot water bottle, placing a temperature sensor on the bottle and putting the thermal clothing over the bottle. Then the drop of the temperature could be logged over time. I would also measure the temperature of the air in the room and weigh the item of clothing excluding the sleeves. I would perhaps repeat the experiment with an additional, unvarying layer (e.g. a thick jumper) and with a fan blowing on the bottle/clothing from a fixed angle and distance. I could use a computer fan with known manufacturer specifications to give an indication of the amount of air being moved. I suppose I would also need an accurate hygrometer to know how cooling the moving air would be?

Do I need other sensors? Should I redesign the experiment?

I want to produce a table that will allow me to determine which clothing offers the best weight to insulation ratio and the best cost to insulation ratio. I guess I'll need to record the dimensions of the garments since some will be more generous than others.

Are the thickness and permeativity to sweat worth consideration?78.148.109.47 (talk) 05:40, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- The thermal performance of some garments is likely to vary between them being worn, and simply draped over an object (e.g. thermal underwear is generally stretched when worn). MChesterMC (talk) 09:27, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- ...which can be good or bad, as it may restrict heat loss by air circulation. At least in Germany, some major outdoor stores have cold chambers with infrared cameras where they allow you to try out your particular piece of clothing on your particular body, and look at the heat loss. Some also simulate wind in the chamber periodically. However, this is more a marketing gimmick (with windows for your friends to look in and make fun of you), and probably not suitable for exact measurements or large-scale comparisons. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 10:56, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- One point that hasn't been mentioned yet - you need a control for your experiment to have meaningful results. A hot-water bottle that's not wrapped in anything would be a possibility. Note also that the results will depend on the temperature (and humidity) of the room, which (presumably) isn't very precisely controlled, so you'll need to factor this in. A third point - weight is not the only important parameter when it comes to how comfortable clothing is, otherwise we'd all wear polystyrene clothing in winter... Tevildo (talk) 19:05, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- There is an important difference between a hot water bottle and the human body. We generate heat internally - so the temperature of a human wouldn't vary much over the duration of the experiment, although we might have to resort to shivering and such to keep the body at the right temperature throughout. But the hot water bottle will gradually cool off. So perhaps we could imagine some kind of garment that releases heat very easily at body temperature, but insulates more and more effectively as the temperature drops (or vice-versa). That garment would perform much better in the experiment than it would with a human subject. Now, I can't think of a material that would act like that - but the whole thing about an experiment is to find that out and not be tricked by things like that. SteveBaker (talk) 21:15, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Then use an electric blanket. Changing out the three-position switch on most with a variable rheostat should allow you to generate a constant temperature. You wouldn't even need a blanket to get to 98.6; you'd merely need the surface of the blanket to be able to maintain skin temperature, which for most people is somewhat less than body temperature. Use an electric blanket, calibrate it to output constant skin temperature, and wrap it in various fabrics. Measure the rate at which the outside of the fabric heats up, and you'll know which fabrics are better at retaining heat and which release it faster. --Jayron32 03:05, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- It seems to me that the technique will measure diffusive cooling pretty well but won't measure radiative cooling. I don't know how important that is on the whole -- it definitely comes into play in some situations. For example a person inside a tent at night will stay warmer than a person outside under a starless sky, even if the air temperature is the same and there is no wind, because the tent reflects radiation back. Looie496 (talk) 02:45, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Something that hasn't been mentioned is how you will secure the fabric to the hot water bottle, and how the assembly will be held in the test chamber. I would suggest you sew the fabric samples into identical "water bottle cozy" shapes, such that you can slip the water bottle in and out, with a hook sewn in so you can suspend the assembly. This will help to ensure identical test conditions, which you won't get by just draping fabric over the hot water bottle. StuRat (talk) 02:53, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

As a home setup that is simple and economical, what about having a glass with a fixed amount boiling water surrounded with insulation except at the top which would have the garment, being careful not to touch the water, and then after a fixed amount of time, measure the temperature and the weight of the water, that will give you a relative measurement of the thermal insulation and how well the garment can "breath". You could also touch the garment to see if it feels wet. If you repeat the experiment with the same setup every times and compare the data for each garment you should get a good idea of the relative merit of each garment. Obviously a much better test would be to have someone wear the garment and do a standardized workout and ask for their impression, that would be a much more thorough and more meaningful evaluation. Joc (talk) 18:50, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Shear strength of soil[edit]

Does the size of aggregate in soil affect internal friction angle? My assumption is that finer aggregates are more likely to be rounded reducing it and also means there would be more weakness planes in between aggregates reducing cohesion. Am I correct? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 194.66.246.26 (talk • contribs) 09:00, 14 November 2014

- I'm not sure what you mean by "aggregate" here, as this normally refers to a construction material of specially graded material rather than soil. As stated in the soil article: "Soil particles can be classified by their chemical composition (mineralogy) as well as their size. The particle size distribution of a soil, its texture, determines many of the properties of that soil, but the mineralogy of those particles can strongly modify those properties. The mineralogy of the finest soil particles, clay, is especially important." In other words, the type of material at least as important than the grain size. And you certainly can't assume that finer grains are more likely to be rounded.--Shantavira|feed me 16:39, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, size of aggregate will affect shear strength, but I agree with the above that smaller particles are not necessarily more rounded. The word "aggregate" is indeed used in soil science (in the field of study, as well as our related articles). We have pretty good articles at soil structure and soil mechanics that discuss the effect of grain size and other features on soil properties. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:48, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

Why the DAF-2 gene is not extinct?[edit]

Hi there,

I've read about Daf-2, and I wonder why that gene has been surviving?

Exx8 (talk) 10:29, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Because organisms who carry the gene don't die before they have a chance to pass it on to offspring. --Jayron32 10:40, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if an allele does confer some disadvantage, it may remain in the population indefinitely if it also confers some benefit. In this case, DAF-2 seems to have a functional role in regulating reproductive development, and knocking it out may indeed prevent the organism from being able to reproduce at all. Also, the locus takes part in controlling formation of Dauer_larva, which seems to confer a large benefit for the overall population. Some academic papers on the topic here [1] [2]. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:42, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Also note that there's an advantage to a species to have shorter lifespans. By not competing with new individuals, the dead worms make room for a new generation, with new genes, and hence increase the rate at which the species can adapt to changing conditions. There are also advantages to longer lifespans, such as having time to learn more and pass that info down, but this applies mainly to more complex organisms. For worms, the obvious advantage would be the chance to reproduce more (keeping in mind, as stated, the decreased chances for survival of the offspring due to more competition). A variable life span might be better still, where, if resources are unlimited, reproduction rates and lifespans are both maximized. StuRat (talk) 15:42, 19 November 2014 (UTC)

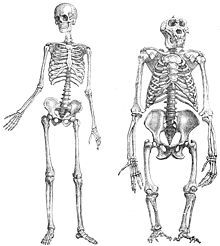

Uniqueness of Human Bones?[edit]

If presented with a *large* box containing one set of adult male bones each from the 7 species of Great Apes how many of the bones of the Human would be distinguishable from the others 1) by a layman, 2) by a Forensic Anthropologist without tools 3) by a Forensic Anthropologist with a full lab. I'm guessing #3 would be all, but for #1, I'm guessing a good number, but I'm not sure if #2 would be all (Free floating ribs and individual vertibrae for example, I guess would be tough. (Would adding any other animal beyond the great apes make things more complicated other than simply increasing the number of bones.Naraht (talk) 15:16, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- For #2, it's going to vary a great deal depending on the background of the individual. Primatology is often not part of the curriculum for, say, undergrad anthropology courses. It would be quite easy to get a doctorate in that field without any more than a passing knowledge of what chimp bones look like. The advantage they'd have over a layperson is their deep familiarity with human osteology. On the other hand, if their undergrad work or grad studies included courses in primatology and/or palaeoanthropology and/or comparative anatomy, then they'd be much better off. Even having a personal interest would greatly increase their ability. The answer for #1 would range from folks with almost literally no knowledge of what a skeleton looks like (I've seen an archaeology undergrad identify a squirrel pelvis as its skull) all the way to amateur bone hunters that could give the pros a run for the money. For #3, the biggest piece is probably not having a "full lab", but having a decent light and magnifying lens with a really good book. Matt Deres (talk) 16:09, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- If the bones are fresh enough, DNA analysis should be able to cluster them into disjoint sets easily enough with a good lab. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 19:21, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- Agreed. My point was simply that the expensive stuff is not necessary. Visual examination, especially with the aid of a diagnostic reference book, would be enough. Matt Deres (talk) 15:31, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- The human foot, skull, and teeth are so different from the other apes, I would expect a high-school biology educated layman who could identify these would know right away whether he was dealing with an ape or a human. Likewise, the limb proportions, relative length of the thumb, pelvis breadth, spine curvature, location of the foramen magnum, ribcage shape, and bowing of the legs are quite distinct. Many of these things are diagnostic of human, non-human on their own, and even if you only had a hand, if you knew how to articulate it it would be quite obvious from the thumb and finger proportions. See this website on man vs gorilla, these images at google, and our articles, human leg and comparative foot morphology. μηδείς (talk) 23:20, 14 November 2014 (UTC)

- As for #1, the skull alone should tell the average layman whether it's a human or some other extant primate. However, if you included some extinct primates, like Neanderthals, that would make it tougher. The remaining bones would be harder to identify, in isolation. Only by laying out the bones in the right order to reconstruct the individual would you get a sense for the proportions of the bones, and hence the species. A further complication would be if the set of bones was atypical for that species. For example, the Elephant Man's skull might be difficult to identify as human. StuRat (talk) 15:48, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us. The premise is a full set of adult male bones, so the skull alone is the end of the story. Even comparing the femur and the pelvis is enough to draw an instant conclusion. Once you've found a heel the quiz is over. μηδείς (talk) 19:43, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- The original question was how many of the individual bones could be identified as human - clearly, identifying a set if you know they all belong together is easier. Dealing with adult specimens makes it simpler though - if you don't know the age, the size may not help much, and the differences between species tend to become more apparent with age. AndyTheGrump (talk) 19:56, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, but we are still presented with a full set of bones from two individuals, not just one carpal bone, which are the only bones I can see as problematic for a layman with a book, although they are bigger in gorilla hands than the are in ours.

- If the sets could be sorted (a layman with a book should be able to do this) none of the bones would be mistaken. A forensic anthropologist would not need a lab, as he'd rearticulate the human first, from head down and sine out, then the gorilla, then check for mistakes. The entire anatomy of a human is modified by two things. The human hands are designed to allow the tip of the thumb to touch the tips of all four fingers, not for brachiation or knuckle walking

- The rest of the skeleton, the feet, legs, pelvis, spinal curvature, and base of the skull are all designed for a permanent upright stance. our legs are long, straight, gracile and knock-kneed compared to apes. Our pelvis is small compared to our femur, but our head is large compared to our pelvis. The hole where our spinal chord enters the skull is on the bottom, in apes further towards the back.

- As intelligent social animals, we don't have fangs for canines, but we do have chins and foreheads, effectively expanding our faces and brain capacity in comparison to apes. The list is endless. μηδείς (talk) 05:02, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed"? AndyTheGrump (talk) 05:06, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- You obviously know exactly what was meant, or you wouldn't have asked the question. So I'll just assume you are particularly grumpy today, and ignore it. μηδείς (talk) 20:41, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- Design is just an expression, anyway. InedibleHulk (talk) 08:04, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed" as in "designed by Mother Nature," i.e. by evolution. Not actively designing like an architect, but passive design by natural selection. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 13:37, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- He could also be thinking of the design vs engineering distinction. InedibleHulk (talk) 16:11, 18 November 2014 (UTC)

- "Designed"? AndyTheGrump (talk) 05:06, 16 November 2014 (UTC)

- The idea that there's a binary determination between same-species/not-same-species, and that the determination is "can interbreed" is simplistic. Even among extant species that's kind of the "high school" understanding of the subject, and when comparing long extinct species with modern ones the question is even more complicated.

- Beyond that, we don't even know if Homo Sapien/Neanderthal breeding normally produced fertile offspring, or just on very rare occasions. (Just like Lion/Tiger breeding will usually create infertile offspring, but on rare occasions the offspring is fertile. Does that automatically make them the "same species"? Clearly not.)

- In fact, while the theory that our Cro-Magnon ancestors interbred with Neanderthals has gained a lot of support, it is far from proven, and even among supporters of the theory, many of them believe that it only 'worked' with Cro-Magnon mothers, and didn't work the other way around. Does that make them the same species? Or different species? Neither. "Species" is an arbitrary distinction. Anyone suggesting otherwise for the purposes of nit-picking is more wrong than the person they're nit-picking! 75.69.10.209 (talk) 07:29, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- You contradict yourself. You say a binary distinction is arbitrary, and then you ask us to draw distinctions. You know very well that interbreeding did take place and did produce fertile offspring, and your nitpicking here is way off topic. I said "Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us." Stu could have asked for a clarification, but he did'nt. Presumably you also know ...Nevermind, I am not going to take you seriously. Stu can read biological species concept if he's interested. μηδείς (talk) 18:35, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Sure, there is a gray area. But given ligers and wholopins and tomacco (nicotine-overdose danger tomatoes(!), "can interbreed (ever)" seems too generous for a useful concept. "(50%/number of matings in a male's life (unpremature death, to satiety)) of inter-group matings with nubile females at random point in menstrual cycle produce 1 fertile offspring" through "has half the rate of fertile offspring as intra-group matings" seems like a more useful gray zone. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 20:24, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Unless your point is that Neanderthals were apes, you're arguing OR about a dead population, so we can't run any experiments, SMW. But we can say that there's more Neanderthal blood out there now than there ever was when they were a distinct population, since at a low estimated end of 2% of the extra-African genome, that's the equivalent of 100,000,000 descendants, easily. See this comparison of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, and Homo sapiens sapiens. μηδείς (talk) 20:39, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Further clarify for SMW. If you haven't read biological species concept, I suggest you do. What matters with hybrids in determining species is if they back-breed into one or both of the original populations. If the hybrid form is infertile, or more poorly adapted to its environment than its parents were to theirs, it will be unlikely to have children of its own, and thus gene transfer between the populations won't occur.

- But in the case of Neanderthals, the evidence is that like chimps, early bands of modern humans lived in groups of about thirty. Hence, when two groups met, there was probably competition for a territory, and relations would have been unfriendly, so that even if the two groups could interbreed, one might kill off the other before the chance occurred. The general belief is that population pressure from H. sapiens sapiens with its better tool kit drove H. sapiens neanderthalensis extinct.

- If the modern humans outnumbered the Neanderthals 20 to 1, a 2-5% flow of genes into the modern human population would show significant enough interbreeding to call the two groups subspecies of the same species according to the biological species concept. Obviously many hybrid offspring did mate with modern humans, or we would not see such a high frequency of Neanderthal genes in our genome. I am not sure how this panned out, but in 2013 a putative hybrid was found in Italy. Given that very few skeletons ever fossilize, this would be significant as well. μηδείς (talk) 22:41, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- Sure, there is a gray area. But given ligers and wholopins and tomacco (nicotine-overdose danger tomatoes(!), "can interbreed (ever)" seems too generous for a useful concept. "(50%/number of matings in a male's life (unpremature death, to satiety)) of inter-group matings with nubile females at random point in menstrual cycle produce 1 fertile offspring" through "has half the rate of fertile offspring as intra-group matings" seems like a more useful gray zone. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 20:24, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- You contradict yourself. You say a binary distinction is arbitrary, and then you ask us to draw distinctions. You know very well that interbreeding did take place and did produce fertile offspring, and your nitpicking here is way off topic. I said "Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us." Stu could have asked for a clarification, but he did'nt. Presumably you also know ...Nevermind, I am not going to take you seriously. Stu can read biological species concept if he's interested. μηδείς (talk) 18:35, 17 November 2014 (UTC)

- The original question was how many of the individual bones could be identified as human - clearly, identifying a set if you know they all belong together is easier. Dealing with adult specimens makes it simpler though - if you don't know the age, the size may not help much, and the differences between species tend to become more apparent with age. AndyTheGrump (talk) 19:56, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

- Neanderthals were human, they interbred with us. The premise is a full set of adult male bones, so the skull alone is the end of the story. Even comparing the femur and the pelvis is enough to draw an instant conclusion. Once you've found a heel the quiz is over. μηδείς (talk) 19:43, 15 November 2014 (UTC)

Dowel action[edit]

What is dowel action on a concrete bean in very simple terms? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 194.66.246.59 (talk • contribs)

- It is a "beam", not a "bean". Dowel action is the shear resisted by the reinforcement of the concrete.

- We have articles on beam_(structure) and reinforced concrete and rebar and shear strength. Here are a few slides that explain dowel action with illustrations [3] Also, please sign your posts with four tildes, like this ~~~~ SemanticMantis (talk) 22:03, 14 November 2014 (UTC)