Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Language/2009 March 17

| Language desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < March 16 | << Feb | March | Apr >> | March 18 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Language Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

March 17[edit]

Passover and Easter -- translations and etymologies[edit]

Co-Wikipedians (Wikipedian colleagues), can you please provide etymologies for as many as possible of these names for Passover and Easter in different languages?

http://multilingualbible.com/exodus/12-11.htm -- http://multilingualbible.com/luke/22-1.htm -- http://multilingualbible.com/1_corinthians/5-7.htm -- Wavelength (talk) 00:22, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Well, anything like "pascha" or "pesach" comes from the Hebrew, so that covers a great majority of them. The Arabic for Easter, Eid al-Qiyamah, literally means "Feast of the Resurrection". Adam Bishop (talk) 05:31, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- The Irish and Gaelic names also come from Pascha, with a very early change of p to c. A lot of the Slavic names - the ones looking roughly like "velikden" or "veliknoch" - mean "great day" or "great night", respectively. The Germanic names like "Easter" and "Ostern" are supposed to come from the name of the pagan Germanic goddess of the dawn and are thus related to the word "east". —Angr 07:05, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- South Slavic variants "uskrs"/"vaskrs" are related with verb "uskrsnuti", (now) meaning "resurrect". The etymology is uncertain; according to one web page, possible roots are obsolete verb "krsnuti" (revive) and "krês" (spark, fire). No such user (talk) 08:38, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Why are we filling this page up with a table whose entire contents either are at wikt:Easter and wikt:Passover or should be added to those pages? --ColinFine (talk) 08:20, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- The "languages" list on the sidebar at easter seems to be quite complete. Just click on the language links and copy out the words. Passover has a shorter list because many languages seem to have included it as part of their Easter page. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 14:35, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- The Irish and Gaelic names also come from Pascha, with a very early change of p to c. A lot of the Slavic names - the ones looking roughly like "velikden" or "veliknoch" - mean "great day" or "great night", respectively. The Germanic names like "Easter" and "Ostern" are supposed to come from the name of the pagan Germanic goddess of the dawn and are thus related to the word "east". —Angr 07:05, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Plattdüütsch : 3 terms Oostern, Paaschen or Paasch. The etymology of the modern term Oostern is derived from the German Ostern:

- In the time of the Teutonic (Germanic?) tribes had a pagan Spring festival that was named after a goddess. Old English texts identify this goddess' name as Eostrae. This seems to be the same goddess as the vedic ursa, Ancient Greek Eos and Latin Aurora. That led to the conclusion that this goddess was the goddess of Light and that her festival had something to do with the increase of light in Spring. That's what Beda Venerabilis surmised in his eight century text "de temporum ratione" Jacob Grimm seconded this opinion whereas most other researchers deny the existence of such a goddess in the Germanic panthenon. (Original source: Duden)

- Other sources think that the term "Oostern" is derived from medieval tradition of having Baptisms in the mornings. That is why the celebration of baptism was named after the germanic name for dawn.

- Honorius Augustodunensis postulated in the 12th century that "Oostern" was derived from "Oosten" (east). This being the direction the light of dawn was seen in, which signified resurrection from the dead.

- Yet another explanation derives the word "Oostern" from the Latin Christian name for the Easter week: albae paschales (white garments of the newly baptized ). The short form albae was translated to the Germanic language as eostarum.

- Entymologist Jürgen Uloph says the Northgermanic languages have a family of words that would fit Oostern: ausa (pouring water) and austr (watering).The word Oostern originated in the baptism, where people got water poured over them. Baptism is the main part of mess for Easter night.

- The old plattdüütsch words for Easter - Paaschen or Paasch - are derived from the Jewish celebration of Pessach (Passa). (taken from from nds:Oostern.)76.97.245.5 (talk) 18:56, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

Passover: the Chinese name for the holiday (逾越節, yuyue jie)is literally the Festival of Passing Over. The Korean name is directly derived from the Chinese name. The Japanese name is entitled 過越 (sugikoshi), which also literally means "passing over." The Japanese name for the seder is the Passover Ceremony (過越祭), also alternately called the Ceremony of Unleavened [Bread] (除酵祭). Although I'm not certain, I'm pretty sure it's a safe bet that the Vietnamese name is also derived from the Chinese name, with the word order reversed.

Easter: In Chinese, it is literally the Festival of the Resurrection (fuhuo jie 復活節), which is used for Korean and Japanese as well (Japanese uses 祭 instead of 節). It looks like the Vietnamese term might have been derived from 复生, which is synonymous with 復活 (this is pure speculation on my part). Generally speaking, in the region which has been termed the Sinographic Cultural Sphere (漢字文化圈, countries where Classical Chinese was used as the medium of written communication prior to the modern era), proper nouns are derived from the Chinese term. Hope this helps. Aas217 (talk) 16:18, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- The Japanese one for 'Passover' literally means 'passing over', as in 'going over [something]', while 'Easter' in Japanese literally means 'The Celebration of Coming-Back-To-Life'.--KageTora (talk) 22:03, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Regarding the Japanese sugikoshi, I have little add to the above. It is a fairly recent expression introduced via translation. Early citations for sugikoshi and sugikoshi no iwai are 1888 and 1880, respectively. As for fukkatsusai, it is a combination of fukkatsu "revive, resurrection" and sai "festival". I see a citation from 1909, but that can probably be pushed back a few decades. You can probably find older obsolete expressions in the c. 16th century religious texts introduced to Japan by the Portuguese missionaries. A good place to begin is in volume 25 of the Nihon Shisō Taikei (1970, Iwanami Shoten). Bendono (talk) 14:44, 18 March 2009 (UTC)

- Hungarian "húsvét", doesn't seem to have a definite known etymology. "hús" means "meat" and "vét" is commonly thought to derive from "vétel", meaning "to purchase". Hence "purchase (or receive) meat". Which allegedly would refer to the breaking of the fast at easter. --Pykk (talk) 13:14, 18 March 2009 (UTC)

- For Persian, Passover is "Pasha", and Easter is "Eid Pak", which seems to mean "feast of cleansing" or something. In Urdu the words are "Pesag" and a transliteration of plain old "Easter". Adam Bishop (talk) 14:01, 18 March 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you all very much for your answers. -- Wavelength (talk) 04:26, 19 March 2009 (UTC)

Just as a side note, we have an article on the sinosphere. --Kjoonlee 14:15, 19 March 2009 (UTC)

Vietnamese

vi:Lễ Phục Sinh comes from Lễ: holy day; Phục: return/spring back; Sinh: birth. Together it means a holy day to commemorate Jesus' "rebirth" from the dead.

vi:Lễ Vượt Qua comes from Lễ: holy day; Vượt: elude/fast escape/running; Qua: go past. A holiday to celebrate an escape. 70.253.81.188 (talk) 06:56, 23 March 2009 (UTC)

Quote often misattributed to Dan Quayle[edit]

I know that Quayle didn't really say "I was recently on a tour of Latin America, and the only regret I have was that I didn't study Latin harder in school so I could converse with those people" but it's a comment that often gets attributed to him on those list of quotations websites.

Does anyone know who actually said it? --90.240.171.128 (talk) 12:20, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- No one actually said it. Claudine Schneider claimed Quayle said it, but she was just kidding. See [1]. —Angr 12:45, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Snopes.com has the answer. - X201 (talk) 12:44, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- In an earlier generation, Ma Ferguson was often attributed with saying, "If English was good enough for Jesus, it's good enough for me" (or according to Wikiquote, "If the King's English was good enough for Jesus Christ, it's good enough for the children of Texas!")...

-- AnonMoos (talk) 12:51, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

-- AnonMoos (talk) 12:51, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Heh. My own great-grandmother said if the King James Version was good enough for St. Paul, it was good enough for her. —Angr 13:47, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- George Bernard Shaw had it drummed into him as a child that God was not only an Englishman but a Protestant to boot. -- JackofOz (talk) 20:05, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

German[edit]

In German, the digraph EI is red as [aɪ] (ah-ee), while IE is usually [iː] (ee). My question is: what's the reading of th trigraph EIE? Does it change from word to word? --151.51.6.83 (talk) 14:12, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- It's usually [aɪ.ə] (e.g. freie is two syllables: frei-e), though in some words it's [e.iː] (e.g. kreieren is three syllables: kre-ie-ren). —Angr 14:20, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Danke schön! --151.51.6.83 (talk) 14:24, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

The Red Sea - Mistranslation[edit]

I have heard on numerous documentaries that The Red Sea (of Moses) was actually a mistranslation of the original Hebrew 'Yam Sūph', which actually means 'The Reed Sea'. However, this was a mistranslation whisch occurred when it was translated into Greek. This continued into Latin, and so on into English. I find this curious, as 'red' looks like 'reed', plus, there is actually a Red Sea. Can anyone supply any information on this, such as why it was mistranslated, what is the Greek for 'red' and 'reed', and anything else which may be helpful?--KageTora (talk) 17:32, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- For what it's worth, the Red Sea is called Ερυθρά Θάλασσα in Greek (red is ἐρυθρός), and reed is καλάμι. — Emil J. 17:43, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- At the risk of stating the obvious, I would like to point out the articles Reed Sea and Yam Suph. Pallida Mors 18:34, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

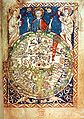

- It has nothing to do with the English words "red" and "reed" -- on some medieval maps in Latin, the red sea is colored in red or maroon, while other seas and oceans are blue... AnonMoos (talk) 18:55, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- There are other places in the Bible where the Red Sea is mentioned...Joshua 2:10 for example, Rahab mentions the story, and 1 Kings 9:26 mentions the Red Sea as the same place we think of. If it's a misunderstanding, it's based on more than one passage. But is it really so hard to believe God parted the Red Sea, if you can accept all the other things that happen in the Bible? The more absurd it is, the more miraculous it is. What would be so great about parting the waters of some swamp? Adam Bishop (talk) 20:05, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Modern Greek has some neuter nouns which, in the singular, end in an iota preceded by a consonant. My guess is that none of these nouns existed with that ending in Classical times. For the word for "reed", the Bible uses κάλαμος (nominative singular) at Revelation 11:1. See http://multilingualbible.com/revelation/11-1.htm, which has several Greek versions.

- This is from List of country name etymologies.

- Eritrea: Named by Italian colonizers, from the Latin name for the Red Sea, Mare Erythraeum ("Erythraean Sea"), which in turn derived from the ancient Greek name for the Red Sea: Ἐρυθρά Θάλασσα (Eruthra Thalassa).

- According to the Bible, the Red Sea was divided so that the Israelites could cross to the other side, but it was brought together again and drowned the pursuing Egyptians. See http://nasb.scripturetext.com/exodus/14.htm.

- -- Wavelength (talk) 20:42, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Ok, so the 'mistranslation' was basically the Greek translator not actually knowing anything about Middle Eastern geography besides the obvious things, like big seas (one which was called the Red Sea, for example) and not little ones (like 'Reed Sea')? That seems to make sense, and looks like it has nothing to do with a linguistic mistake, which is what I was thinking. The guy(s) just probably thought, 'Well, the only sea I know of round there is the one they call the Red Sea, so this Yam Suph thingummyjig is probably the local name for that'. I was aware of the fact it had nothing to do with the English 'red' and 'reed', as Ancient Greeks didn't speak Modern English (only in films), and was wondering whether it was a Greek word which was mistranslated into Latin (sounding like another Greek word), or, more likely a Hebrew word sounding like another Hebrew word mistranslated into Greek. Anyway, seems like it's cleared up. Thanks.--KageTora (talk) 20:46, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Unfortunately, this all seems to be a little confused -- the Hebrew Bible has only the single phrase Yam Suph ים סוף which is used in all contexts (the Exodus narrative, the body of water adjoining Solomon's port at Eilat or Ezion-Geber, etc.) The translators of the Septuagint naturally equated Yam Suph with the Greek toponym corresponding in meaning to the English term "Red Sea" (but also to the English term "Indian Ocean"). This Greek Ερυθρη Θαλασσα == Hebrew ים סוף equivalence was not based on translating the literal meaning of Hebrew Suph in Yam Suph. It was only much later that relatively modern interpreters came up with the possibly literal translation "Sea of Reeds", which some of them then applied specifically to the Exodus account in opposition to the Gulf of Aqaba (a distinction which does not seem to exist in the terminology used in the Bible itself). AnonMoos (talk) 23:23, 17 March 2009 (UTC)

- Suph by itself means "reeds" or "rushes" (the KJV uses "flags" for some reason), as at Exodus 2:3–5 and Isaiah 19:6. —Angr 07:04, 18 March 2009 (UTC)

The term ףוס־םי ("Red Sea") is not an innovation by deuteronomistic tradents, since it already occurs in the Song of the Sea when Pharaoh and his army are described in Exod 15:4 as being destroyed. ףוס־םיב The meaning of the phrase in the Song of the Sea provides an important starting point for interpreting the development of this term in deuteronomistic tradition, and, indeed, there is a history of debate around this problem beginning even with the translation of the Hebrew. The translation "Red Sea" is based on the LXX, which translates the phrase with the Greek εν ερυθρᾳ θαλασση. A competing translation, "Reed Sea" is also common, going back to such early commentators as Jerome and Rashi, who reasoned that when the Hebrew word ףוס is used alone, it designates "reeds" or "rushes." The translation "Reed Sea" received support in more recent scholarship when the Hebrew ףוס was considered to be a loanword from Egyptian twf(y), meaning "reed" or "papyrus." The debate over translation has tended to focus on geography in order to determine the route of Israel's exodus, in which case it is argued that the Reed Sea designates a different body of water further north than the Red Sea (i.e., the Gulf of Suez). This debate is not particularly helpful for interpreting Exod 15:4, since the geography of the exodus does not appear to play an important role in the song. As a result, neither translation alone probes the significance of the phrase in its context within the Song of the Sea. Dozeman, T. B. (1996). God at War: Power in the Exodus Tradition. pp. 60-1. OCLC 32349639

—eric 20:24, 18 March 2009 (UTC)

- [Hebrew is written and read from to right to left. Therefore, ףוס־םי should be ים־סוף and ףוס־םיב should be בים־סוף.

- -- Wavelength (talk) 23:55, 18 March 2009 (UTC)]

Three maps with the Red Sea shown in red (around 1 o'clock - 2 o'clock): AnonMoos (talk) 20:30, 17 March 2009 (UTC)