Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Humanities/2014 July 13

| Humanities desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < July 12 | << Jun | July | Aug >> | July 14 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Humanities Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

July 13[edit]

Herod the Great in Art[edit]

Hi, can you help find out who is the creator/source of this print(commons:File:HerodtheGreat2.jpg) of Herod the Great (or maybe an ancestor)? Right now all I got is the year 1754 and photo coming from Hulton Archive. trespassers william (talk) 01:20, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- If it is any help, the inscription "Herodes Ascalonita" is the title of a play by the Spanish writer Cristóbal Lozano. There's no English language Wikipedia article about the author, but the Spanish language article is here. Perhaps the print comes from a printing of his play. I can find no Wikipedia articles in any language about the play, but if you search Google for "Herodes Ascalonita", you can find it. --Jayron32 04:18, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I looked that way but don't think it helps. An 1757 edition here doesn't have the image, and the name Herodes Ascalonita goes, I think, as far as Eusebius. However, the proximity of years is suspicious. trespassers william (talk) 13:10, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I don't particularly understand how "Ascalonita" makes sense. Ascalon (Ashkelon) was one of the few areas near Judea not conquered by the Maccabees, and Herod's family came from Edom, not Ascalon. I have a map of "Palestine under the Herods" which shows Ascalon as not included in the "Boundary of Herod's kingdom at its greatest extent"... AnonMoos (talk) 18:27, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Yeah whenever I bump into Eusebius he gets something wrong. See The Church History of Eusebius. Ch VI, .2. The editor (

Philip Schaff?Arthur Cushman McGiffert) notes:- 89:90

- Yeah whenever I bump into Eusebius he gets something wrong. See The Church History of Eusebius. Ch VI, .2. The editor (

- On Africanus, see Bk. VI. chap. 31. This account is given by Africanus in his epistle to Aristides, quoted by Eusebius in the next chapter. Africanus states there (§11) that the account, as he gives it, was handed down by the relatives of the Lord. But the tradition, whether much older than Africanus or not, is certainly incorrect. We learn from Josephus (Ant. XIV. 2), who is the best witness upon this subject, that Antipater, the father of Herod the Great, was the son of another Antipater, or Antipas, an Idumean who had been made governor of Idumea by the Jewish king Alexander Jannæus (of the Maccabæan family). In Ant. XVI. 11 Josephus informs us that a report had been invented by friends and flatterers of Herod that he was descended from Jewish ancestors. The report originated with Nicolai Damasceni, a writer of the time of the Herods. The tradition preserved here by Africanus had its origin, evidently, in a desire to degrade Herod by representing him as descended from a slave.

- 89:91

- Ascalon, one of the five cities of the Philistines (mentioned frequently in the Old Testament), lay upon the Mediterranean Sea, between Gaza and Joppa. It was beautified by Herod (although not belonging to his dominions), and after his death became the residence of his sister Salome. It was a prominent place in the Middle Ages, but is now in ruins. Of this Herod of Ascalon nothing is known. Possibly no such man existed.

- trespassers william (talk) 19:28, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Damn, Getty are using 1754 as a generic year. [1] [2]. trespassers william (talk) 17:31, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

Are there Christian sects that have become an ethnoreligious group?[edit]

What I mean is, the Hui people are a group of Chinese Muslims who tend to be more Chinese than they are Muslim. I am wondering if there is an ethnoreligious group that identifies with some sect of Christianity, but may not practice that form of Christianity and only identify with that form of Christianity because of a long line of ancestors and family customs and rituals. 65.24.105.132 (talk) 16:59, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- There are many people out there who'd describe themselves as "cultural catholics" (or other Christian groups) who identify because of ethnicity rather than theology. I'm from Boston, so Irish Catholic comes to mind. Probably lots of others. Staecker (talk) 17:43, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- So, does that mean that a person of Irish Catholic descent may be affiliated with the Irish Catholic culture but may observe something differently entirely, such as Protestantism? 65.24.105.132 (talk) 18:51, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Probably not, but they could easily be atheists and not believe or live by Catholic teachings, but still go to church, receive sacraments, etc. In the extreme, consider something like the common media portrayal (no idea if it's true) of strong catholicism in the mafia. Staecker (talk) 12:34, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- So, does that mean that a person of Irish Catholic descent may be affiliated with the Irish Catholic culture but may observe something differently entirely, such as Protestantism? 65.24.105.132 (talk) 18:51, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I am thoroughly confused by the opening statement, "more Chinese than Muslim"? How would one think that those would be mutually exclusive states of being. How is being a Chinese national and a follower of Islam conflictory? There are Muslims from just about every ethnicity, race, and nationality you can think of, and I am wondering what the OP thinks that being Chinese would somehow prevent such a person from following Islam? Or more to the point, why does the OP not think that a person could not be fully Muslim and fully Chinese, and would need to be more one tha the other, as if the two ideas were in conflict?Jayron32 19:04, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I take it to mean "tend to be predominantly Chinese in culture with some Muslim influences"; traditional Chinese culture is radically different from traditional Islamic culture. Nyttend (talk) 19:36, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Again,huh? There isn't a unified Islamic culture. Balkan Muslims have a different culture than Indonesian Muslims, have a different culture from west African Muslims have a different culture from Arabic Muslims. Muslims from those cultures would recognize the forms of worship and central tenets of their faith, but would find the food, language, family structures, gender relations, literature, and music to be as foreign as any other randomly selected people groups. What aspects of Islam does one have to abandon to belong to the Chinese culture other than those of the religion itself?--Jayron32 19:45, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- You should read the article on the Hui people. One characteristic of the Hui people is that they refuse to eat pork for religious-cultural reasons, and pork is the most commonly consumed meat in China. 65.24.105.132 (talk) 20:04, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I never said they ate pork. --Jayron32 20:16, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- It's not so much outright abandonment as compromise or syncretism. Consider the profound influence that Confucianism has had on Chinese culture, and the profound differences that it has with core Islamic beliefs, and then throw in the similarly significant and similarly non-Islamic influences of systems such as Taoism and Buddhism; for example, yin and yang have long played a massive rôle in Chinese culture (and other Oriental cultures too), and the concept is very much at variance with Islamic theology, even the most basic tenet of all, tawhid. It's easy to say that someone is more Chinese than Muslim (or more Muslim than Chinese), based on what you deem to be their tendency toward Chinese-based actions and beliefs or toward Islamic-based actions and beliefs. Nyttend (talk) 20:29, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- But they would still regard themselves as 100% Chinese in all the ways that count, and 100% Muslim in all the ways that count. Which they are. -- Jack of Oz [pleasantries] 20:48, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- More to the point: Chinese culture being different from Islam doesn't make Chinese culture a religion, any more than an elephant being different from an apple makes the elephant a fruit. Neither can you use the same logic to make "Muslim" an ethnicity. China is, and has been for millennia, a country with a very diverse religious and ethnic makeup. You cannot speak of "Chinese religion" or even necessarily "Chinese culture" in quite the same way you can speak of "Islam" or "Islamic culture." Sharing a noun does not guarantee that any two concepts can be analyzed as if all their characteristics bore a 1:1 correspondence to one another. Evan (talk|contribs) 18:52, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- It's not so much outright abandonment as compromise or syncretism. Consider the profound influence that Confucianism has had on Chinese culture, and the profound differences that it has with core Islamic beliefs, and then throw in the similarly significant and similarly non-Islamic influences of systems such as Taoism and Buddhism; for example, yin and yang have long played a massive rôle in Chinese culture (and other Oriental cultures too), and the concept is very much at variance with Islamic theology, even the most basic tenet of all, tawhid. It's easy to say that someone is more Chinese than Muslim (or more Muslim than Chinese), based on what you deem to be their tendency toward Chinese-based actions and beliefs or toward Islamic-based actions and beliefs. Nyttend (talk) 20:29, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I never said they ate pork. --Jayron32 20:16, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- You should read the article on the Hui people. One characteristic of the Hui people is that they refuse to eat pork for religious-cultural reasons, and pork is the most commonly consumed meat in China. 65.24.105.132 (talk) 20:04, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Again,huh? There isn't a unified Islamic culture. Balkan Muslims have a different culture than Indonesian Muslims, have a different culture from west African Muslims have a different culture from Arabic Muslims. Muslims from those cultures would recognize the forms of worship and central tenets of their faith, but would find the food, language, family structures, gender relations, literature, and music to be as foreign as any other randomly selected people groups. What aspects of Islam does one have to abandon to belong to the Chinese culture other than those of the religion itself?--Jayron32 19:45, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I take it to mean "tend to be predominantly Chinese in culture with some Muslim influences"; traditional Chinese culture is radically different from traditional Islamic culture. Nyttend (talk) 19:36, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Probably not exactly what you're looking for, but the Subbotniks seem to be/to have been almost Jewish for most practical purposes. They were Jewish enough for nearby communities of Orthodox Jews to intermarry without objection, for example, and they maintained traditionally Jewish customs and dietary restrictions, meaning that they shared the same sense of ethnic isolationism practiced by traditional Jews. That's more of a case of a Christian sect being closely tied to an adjacent ethnic community, however, rather than "becoming" one in itself. Evan (talk|contribs) 12:49, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

(Western) Samoa-American Samoa relationship[edit]

Is there, or has there been in recent years, any substantial support for uniting American Samoa and (Western) Samoa? Not mentioned in Samoa or American Samoa or Samoa-United States relations, as far as I can see; we ought to say "There is" or "There isn't", if we can find some sort of sourcing. Nyttend (talk) 18:06, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- This article provides an interesting commentary on the issue. And here is a more authoritative summary of recent discussions. Ghmyrtle (talk) 14:59, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

Maine and Massachusetts[edit]

Are there any good maps of Maine as a part of Massachusetts before statehood? Was the District of Maine connected to Massachusetts or separate by New Hampshire?--KAVEBEAR (talk) 21:13, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

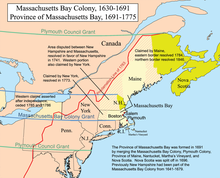

- Not really, they were always separated by the New Hampshire coast. The boundaries between Massachusetts (including Maine) and NH were established in 1741, and have not changed since then. See the attached maps. As New Hampshire was established at Strawberry Banke (modern Portsmouth), it always existed between the two parts of Massachusetts, from the moment of its founding. It grew west and north over the decades as additional settlers moved inland. Briefly, the Province of Maine was an independent colony founded in 1629 at the same time as New Hampshire, but it was absorbed by Massachusetts Bay in the 1650s. New England as a whole was thrown into upheaval during the Edmund Andros years, all of the Northern colonies (New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connectcut, New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey) were reorganized into a single colony, the Dominion of New England. This went out the window with the Glorious Revolution, and the new colonial charters given to Increase Mather during his famous trip to London in 1691 created the new Province of Massachusetts Bay, which confirmed Maine, Plymouth, as well as Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard (formerly oart of New York) as part of Massachusetts. From 1691 - 1741, Massachusetts, New York, and New Hampshire all claimed the land to the north and west of New Hampshire's undisputed claim (the yellow wedge in the second map) but none of the three had any undisupted claim to that land; it was largely unsettled. Part of the problem was that a single governor was given administration of BOTH Massachusetts and New Hampshire during those years, it wasn't until George II named Benning Wentworth as New Hampshire's governor distinct from Massachusetts when New Hampshire was given the land. One could sort of claim that Maine and Massachusetts proper were connected by Massachusetts claim to that land. More reading in this regard can also be found at the article Northern boundary of Massachusetts. --Jayron32 01:23, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

The prophecy of the Three Witches in Macbeth[edit]

In Macbeth, one of the prophecies of the Three Witches is that Banquo himself will not be a king, but he will be father to a line of kings. What exactly does this mean? The play ends with Malcolm being crowned the new king after the death of Macbeth. So, at some point (after Malcolm), can we assume that Fleance (Banquo's son) becomes king? How does the royal succession "switch over" from Malcolm to Fleance? Also: Since the play ends with Malcolm being king, why does Shakespeare include these "after events" as part of his play and as part of the prophecy of the Three Witches? In other words, why does Shakespeare bother to have this prophecy mentioned as part of the play, when the play really never addresses it? What did this "add" to the play? The Three Witches could have just stated all of their other prophecies (about Macbeth); why did they even have to bother with mentioning this one? Thanks. Joseph A. Spadaro (talk) 22:26, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Our article on Banquo states that at the time the play was written, he and Fleance were thought to have been real historical figures, and ancestors to the Stewart/Stuart kings of England and Scotland. Shakespeare was probably attempting to curry favour from the powers-that-be of the time. Rojomoke (talk) 22:34, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Just by the way, you mean prophecy, not prophesy. This is one of those noun/verb splits. Prophesy (pronounced PROF-ess-Sye) is a verb, and means to engage in prophecy. --Trovatore (talk) 23:05, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Correct. That was an error on my part, which I went back and corrected. I think my post actually started out with the verb "prophesy", but then I went in, made some edits, reworded things, and neglected to change the spelling. Thanks. Joseph A. Spadaro (talk) 23:16, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, prophesy is only a verb. Equinox who is a prolific contributor to Wikitionary states that prophecy (verb) is a dated form of prophesy (verb). Is there any citation to support that claim, or to clarify "dated" ? 84.209.89.214 (talk) 23:37, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- Correct. That was an error on my part, which I went back and corrected. I think my post actually started out with the verb "prophesy", but then I went in, made some edits, reworded things, and neglected to change the spelling. Thanks. Joseph A. Spadaro (talk) 23:16, 13 July 2014 (UTC)

- I find it simply allows him to add a future layer to the story. If he'd written down that part, rather than letting it grow in the viewer, it'd become the present. 27 years later, I'm still wondering what Skeletor's survival meant.

- As for becoming a king when you're not a king, that's as simple as killing everyone in front of the line. Not so common by Shakespeare's day, but it was all the rage in Constantine's. Fifth in a row. Helped if you were at least a nephew, but then again, you could've just killed anyone who said you weren't. Banquo's son (or grandson, etc.) may have had the same idea later. InedibleHulk (talk) 00:30, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- As luck would have it, tanistry was legally killed under that King James. So it seems to have something to do with him. Not sure about currying favour, but I'll need a history refresher and some Googling before I can guess any further. InedibleHulk (talk) 02:33, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- Skeletor's bones didn't have any marrow, either, and the time between his fall and today is equal to the time between Constantine III's death and Malcolm III's rebirth. I mean, birth. Or Duncan's, by this count. I think I may be too stoned for serious research right now, but I am learning some relevant things, too. InedibleHulk (talk) 02:45, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- In the source, Banquo conspires with Macbeth, but in the play he's the epitome of innocence. That's just because he was the supposed ancestor of King James, for whom the play was written. All the witchy stuff is also designed to flatter James, who fancied himself an expert on witches and had written a book about their dastardly deeds (Daemonologie). The villain is misled by witches, but his noble ancestor isn't, proving that James came from a long line of witch-rejectors. Paul B (talk) 09:29, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

- It's worth adding that many scholars believe the play was originally much longer, and that the version that survives is a cut-down one, along with some scenes added by Middleton. The prophetic material may have been referred to at more length in the full text. Apparently "weird" bits of gnomic Nostradamus-like prophecy are a feature of Shakespeare's Jacobean plays. In King Lear the fool prophesies a prophecy that Merlin will make in future! (i.e. he makes the prophecy, which is semi-gibberish, and then says that Merlin will make this prophecy some centuries later). Paul B (talk) 09:33, 14 July 2014 (UTC)

Thanks, all. Joseph A. Spadaro (talk) 17:26, 15 July 2014 (UTC)