Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Humanities/2010 October 28

| Humanities desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < October 27 | << Sep | October | Nov >> | October 29 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Humanities Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

October 28[edit]

separation of church and state[edit]

how does the USA separate the church and state if they pay chaplins in their army? wouldn't that be a violation of the separation of church and state law? and what about the senate chaplin? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 97.125.136.30 (talk) 01:38, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Perhaps by providing equally for various religious groups. Bus stop (talk) 01:46, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Separation of church and state in the United States is a theory that is derived from the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. It is by no means law. schyler (talk) 01:52, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

See Marsh v. Chambers (1983) and Are Official Government Chaplains Constitutional?. Basically, government-paid chaplains is a tradition as old as the Constitution, and that was good enough for the Burger Court. —Kevin Myers 01:58, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- This question is discussed well in our Criticism of employing chaplains in the U.S. Armed Forces and Congress article, which among other things points out the US maintains the policy that "military officials must fully accommodate the rights of service members to believe or not to believe in any particular religious doctrine," which means providing military personnel with the means to practice their religion, if they have one and wish to and require a chaplain to do so fully or properly, while on active duty. It does not violate the constitution as long as it does not require anyone to practice or believe in a religion. WikiDao ☯ (talk) 02:19, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Actually, this is sort of interesting, from Army Regulation 165–1:

I wonder if there has ever been a instance of eg. a pagan soldier going to an Evangelical chaplain for "facilitation" of the observance of eg. samhain. I'm finding that difficult to imagine... WikiDao ☯ (talk) 02:47, 28 October 2010 (UTC)"Each chaplain will minister to the personnel of the unit and facilitate the “free-exercise” rights of all personnel, regardless of religious affiliation of either the chaplain or the unit member."

- Actually, this is sort of interesting, from Army Regulation 165–1:

- In the U.S. Bill of Rights, Freedom of Religion has two parts:

- The establishment clause (Congress shall make no law establishing a state religion)

- The free exercise clause (Congress shall make no law preventing the free exercise of a person's religion)

- The issue is that these are often in conflict with one another, especially when it comes to government employees. While congress cannot establish an official religion, it also cannot prevent government employees (military included) from freely exercising their own religion. The issue of chaplains has come down on the free exercise side... --Jayron32 04:17, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Though the issue is not the exercise of the chaplains, but paying them as chaplains. The courts have so far leaned towards saying that getting rid of paid chaplains would inhibit the free exercise of the soldiers. I find that a little dubious — you could have unpaid chaplains that were financed by private money, for example — but I also think we probably should recognize that the military is a somewhat special case from the rest of civil society, and that religion and death are pretty importantly bound up for most people, and paying for a few chaplains probably doesn't cost very much compared to the whole of what is spent on defense. --Mr.98 (talk) 13:11, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

97.125.136.30 -- You may think it's a contradiction, but military and legislative chaplains have existed since the beginning of the U.S., and were established by votes of many of the same congress members who also voted to propose the 1st amendment to the states to ratify... AnonMoos (talk) 04:21, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- That doesn't necessarily mean it applies today. The founders owned slaves as well, but we were happy enough to overturn that. And anyway, as the link above points out, even some of the founders were very against the idea of employing them. --Mr.98 (talk) 13:11, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- However, slavery was affected by the 13th amendment, while no such overt and explicit change to the constitution has affected chaplaincies... AnonMoos (talk) 23:11, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The US Constitution may prefer the seperation of church & state, but this hasn't been practiced. The 1st US President (for example) added onto his inaugural swearing-in "So help me God", something which almost ever President since, has added. Come to think of it, who was the last US President to openly run & serve as an athiest? answer nobody. GoodDay (talk) 13:22, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The principle of "separation of church and state" doesn't preclude individuals in the government from having or expressing religious views. What you're describing would really be described as "separation of religion & state", something relatively few Americans have favored at any time in our history. These days, it seems like we could have, say, an Asian lesbian president before we'd have an openly atheist white male president, as long as the Asian lesbian was a Christian. —Kevin Myers 13:52, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's scary: the most powerful person in the world (military speaking), believes in an invisible man, floating above the clouds. GoodDay (talk) 14:00, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Eh, it's not the belief that bothers me, but the actions that would be an issue. If you act like humans are all we've got, that's enough for me. --Mr.98 (talk) 14:01, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Indeed 99.999% of Christian adherents I know do not spend 12 hours a day praying to God for food, but work for it themselves. It is scary when groups of humans start killing each other because they think their deity is better then all the others and demands the "heathens" to convert or die. Googlemeister (talk) 14:04, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Eh, it's not the belief that bothers me, but the actions that would be an issue. If you act like humans are all we've got, that's enough for me. --Mr.98 (talk) 14:01, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's scary: the most powerful person in the world (military speaking), believes in an invisible man, floating above the clouds. GoodDay (talk) 14:00, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The principle of "separation of church and state" doesn't preclude individuals in the government from having or expressing religious views. What you're describing would really be described as "separation of religion & state", something relatively few Americans have favored at any time in our history. These days, it seems like we could have, say, an Asian lesbian president before we'd have an openly atheist white male president, as long as the Asian lesbian was a Christian. —Kevin Myers 13:52, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

I've specialized in Establishment Clause principles relating to government funding of religious or faith-based religious organizations. Establishment Clause law is complex and clearly political. Most cases are decided 5-4. Mitchell V. Helms and other cases used the concept of neutrality to sanitize possible Establishment Clause violations. An individual actor freely exercising his/her choice supposedly prevents the government from creating an establishment. It is clear that if the Dems are able to increase their representation on the Court, a new principle will emerge. I now see it as a matter of political will. 75Janice (talk) 20:50, 28 October 2010 (UTC)75Janice

- What evidence is there that a majority of Democratic party members or Democratic members of congress favor the abolition of military chaplaincies? AnonMoos (talk) 23:11, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

Western Union memo[edit]

The list of "stupidest things ever said", linked to above, includes this:

"This 'telephone' has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us." --Western Union internal memo, 1876.

I can think of a couple of reasons for saying that - history of telephone says that research was on at the time (simultaneously to developing the telephone, and by the same people?) to send multiple telegraphs over one wire simultaneously using modulated audio frequencies, so voice communication would be a waste of bandwidth (and entail paying for more wires). Besides, there were no exchanges, so if it was to work similarly to the telegraph, you'd have to go to a telephone office to get a telephone operator to read out your message to another, far-away telephone operator, who would write it down so it could be delivered to the person you were calling. Is the memo genuine, though, and what were the real reasons? (Actually that second reason doesn't ring true: reading more of the history of the telephone article, I find "Western Union, already using telegraph exchanges, quickly extended the principle to its telephones".) 81.131.40.225 (talk) 04:29, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

French military[edit]

Why is the French military so much worse than all other European militaries? --J4\/4 <talk> 15:06, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- What makes you think the French military is worse then the Greek military or the Polish military or the Irish military? Googlemeister (talk) 15:14, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The only wars they didn't lose were WWI and WWII, and even then they would've been defeated if America and the UK hadn't saved them. --J4\/4 <talk> 15:39, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- "Worse" is a loaded term. The French kept the Italians to a standstill even while they were being beaten by the Germans at the opening of WWII. The French fought the Germans to a standstill in 1914, pretty much on their own, apart from the BEF. The American showed up at a time when the French and Germans were pretty well exhausted. The Soviets took a long time and terrible casualties to get back on their feet in WWII, and the Russians lost WWI and had a revolution. The Belgians were beaten up in WWI and WWII. The Austro-Hungarians had their problems in WWI. The Americans had to learn from hard experience in both wars. Geography and psychology mean a great deal. The French experience of WWI was formed by the Franco-Prussian War, and their experience of WWI formed their response to the Germans in WWII. Acroterion (talk) 15:50, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- (ec) Just to throw out a few numbers (and I know when it comes to military strength numbers aren't everything) France has 250,000 people in their military not including law enforcement personnel. They have 400+ tanks, 300+ artillery pieces, 80 attack helicopters, around 200 4th generation fighter aircraft, 10 nuclear submarines, an aircraft carrier, and 300 nuclear warheads. Now that might not be the most powerful in the world, but it really is not bad in the numbers department. Googlemeister (talk) 15:58, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The only wars they didn't lose were WWI and WWII, and even then they would've been defeated if America and the UK hadn't saved them. --J4\/4 <talk> 15:39, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Probably the question could be rephrased in more factual and less inflammatory terms as: "Why is it that within the last 150 years France has had two spectacularly sudden military collapses affecting its core territory (i.e. the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871, and the German invasion of May 1940) against opposing powers which on paper didn't appear to have an overwhelming military strategic superiority?" -- AnonMoos (talk) 15:44, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Much better. I think the OP is more concerned with history than present circumstances. Note also that a guy named Napoleon was remarkably successful. In the Franco-Prussian War the Napoleon III talked himself into a disastrous campaign against Prussia that got him captured at the Battle of Sedan, resulting in the occupation of Paris and the loss of Alsace and part of Lorraine. Much of the French trouble with WWI was the result of ossified military leadership and sheer exhaustion - remember that much of the war was fought over the industrial heartland of France, crippling war production and shutting off manpower. Having had that experience, France was not enthusiastic about a repetition in 1940. France also suffered from military leadership that had been formed in 1914-1918 and was trying to fight the last war over again. By coincidence, France was defeated again in 1940 at Sedan. I'd suggest reading some articles on the Battle of France, Franco-Prussian War and First Battle of the Marne for insight. Acroterion (talk) 16:30, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- I thought the French Foreign Legion had a good reputation. Rmhermen (talk) 16:54, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The French Army under Napoleon didn't put on too bad of a show! Neither did the French soldiers under General Lafayette when they helped the American colonists secure independence from Britain. Then let us not forget Joan of Arc, who led the French to final victory in the Hundred Years War.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 17:32, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Can you name a European army that didn't come off worst against the Germans in 1940 or 1941? Alansplodge (talk) 17:53, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Italy? -- 18:02, 28 October 2010 User:Googlemeister

- Erm.. did Italy fight Germany in 1940/41? Don't think so. Alansplodge (talk) 08:20, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Poland?--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 06:14, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- The Polish Army gave a good account of itself but didn't win did it? Alansplodge (talk) 08:20, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- But seeing as how Poland surrendered in 1939, they didn't come off worst in 1940 now did they? Googlemeister (talk) 13:03, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Sorry I misread the question. I believe that in 1940 and 1940 the Germans were regarded as an unstoppable juggernaut rolling enexorably across Europe.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 08:41, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- The Polish Army gave a good account of itself but didn't win did it? Alansplodge (talk) 08:20, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Alansplodge -- Many countries other than France were beaten, but none of them semi-ignominiously collapsed despite being a semi-major military power entrenched behind strong defenses. France certainly has had a number of glorious military victories, but no other major power has a record of two sudden collapses within the last 150 years. As Lady Bracknell might say "To lose one unexpectedly swift defeat may be regarded as a misfortune. To lose two looks like carelessness."

AnonMoos (talk) 19:24, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

AnonMoos (talk) 19:24, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- And if Britain were not an island the chances are they would have been defeated just as swiftly. Jack forbes (talk) 19:29, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Italy? -- 18:02, 28 October 2010 User:Googlemeister

- Can you name a European army that didn't come off worst against the Germans in 1940 or 1941? Alansplodge (talk) 17:53, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The French Army under Napoleon didn't put on too bad of a show! Neither did the French soldiers under General Lafayette when they helped the American colonists secure independence from Britain. Then let us not forget Joan of Arc, who led the French to final victory in the Hundred Years War.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 17:32, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- I thought the French Foreign Legion had a good reputation. Rmhermen (talk) 16:54, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Much better. I think the OP is more concerned with history than present circumstances. Note also that a guy named Napoleon was remarkably successful. In the Franco-Prussian War the Napoleon III talked himself into a disastrous campaign against Prussia that got him captured at the Battle of Sedan, resulting in the occupation of Paris and the loss of Alsace and part of Lorraine. Much of the French trouble with WWI was the result of ossified military leadership and sheer exhaustion - remember that much of the war was fought over the industrial heartland of France, crippling war production and shutting off manpower. Having had that experience, France was not enthusiastic about a repetition in 1940. France also suffered from military leadership that had been formed in 1914-1918 and was trying to fight the last war over again. By coincidence, France was defeated again in 1940 at Sedan. I'd suggest reading some articles on the Battle of France, Franco-Prussian War and First Battle of the Marne for insight. Acroterion (talk) 16:30, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

I have a hard time assuming good faith on this question, considering this edit that the OP just made. --Saddhiyama (talk) 18:43, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Which is just a joke on this old exercise in Google bombing [1]. Quite creative (the original, not this copycat), if a tad bit offensive. Buddy431 (talk) 19:32, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- I am quite familiar with it. Please don't indulge the trolls. --Saddhiyama (talk) 22:31, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- To me this question is nothing but a display of blatant Francophobia. I encounter it constantly whenever people hear my name. Advice to the OP: read the history of France and its contributions to civilisation and then see if you feel like asking the same question.Hmm, I wonder if Harold Godwinson was deprecating French military strength when he received the Norman arrow through his eye?--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 04:57, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Francophobia is certainly part of it, but it's often triggered by perceptions that France has not "declined gracefully" or adjusted to its current real degree of power in the world, and that certain French politicians (such as de Gaulle in 1960's, or a little bit Dominique de Villepain in 2002) are given to pretentiously grandiose proclamations which do not correspond with France's real weight in world affairs or historical performance during the post-Napoleonic period. AnonMoos (talk) 08:02, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- To me this question is nothing but a display of blatant Francophobia. I encounter it constantly whenever people hear my name. Advice to the OP: read the history of France and its contributions to civilisation and then see if you feel like asking the same question.Hmm, I wonder if Harold Godwinson was deprecating French military strength when he received the Norman arrow through his eye?--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 04:57, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- I am quite familiar with it. Please don't indulge the trolls. --Saddhiyama (talk) 22:31, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- He was a vassal of the French king and his army included many Frenchmen from Paris and the surrounding area.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 08:17, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Jeanne -- In the 11th-century, the fact that you owed fealty to a lord who himself owed fealty to the king of France simply did not mean that you had a well-developed "national" self-identification as being French, and to claim otherwise would be quite anachronistic... AnonMoos (talk) 13:12, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Whether the invaders in 1066 felt Norman, Breton, French or just plain greedy was not the point I was trying to make; rather that the army came from Normandy, which is geographically located in France, and they emerged the victors over the Saxons who also did not have an English national identity in the modern sense of the word.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 17:14, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Jeanne -- In the 11th-century, the fact that you owed fealty to a lord who himself owed fealty to the king of France simply did not mean that you had a well-developed "national" self-identification as being French, and to claim otherwise would be quite anachronistic... AnonMoos (talk) 13:12, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- The French military did remarkably well from at least 1300 onwards, other than a few scattered defeats, which are for some reason more well known in the surrounding countries than are their many victories. Quite a lot of recent European history has been trying to prevent the French taking over most of Europe, whilst the country managed to avoid total defeat and conquest even when so many other nations were allied against it. Napoleon, meanwhile, managed to form an empire that sprawled all the way to Moscow, for a little while, and came close to winning again in 1815, even with most of Europe against him. From then on, though, France has not done so well, partly, perhaps, because their main enemy has been Germany, which is known for its huge factories and vast supplies of metal ores. Forget thinking of other countries that did worse in the recent wars, can you think of any country other than Germany that has ever defeated France? 148.197.121.205 (talk) 09:50, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Battle of Dien Bien Phu? Ghmyrtle (talk) 12:32, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- The French military did remarkably well from at least 1300 onwards, other than a few scattered defeats, which are for some reason more well known in the surrounding countries than are their many victories. Quite a lot of recent European history has been trying to prevent the French taking over most of Europe, whilst the country managed to avoid total defeat and conquest even when so many other nations were allied against it. Napoleon, meanwhile, managed to form an empire that sprawled all the way to Moscow, for a little while, and came close to winning again in 1815, even with most of Europe against him. From then on, though, France has not done so well, partly, perhaps, because their main enemy has been Germany, which is known for its huge factories and vast supplies of metal ores. Forget thinking of other countries that did worse in the recent wars, can you think of any country other than Germany that has ever defeated France? 148.197.121.205 (talk) 09:50, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's not really just the fact that France was defeated by Germany which by itself leads to all the jokes (such as the trees along the Champs-Élysées being planted so that the German army can march in the shade etc.); it's the way that the French army seemed to fold like a house of cards in both 1870 and May 1940, despite the fact that on paper it would seem that the military forces of the two nations should have been roughly comparable in strength. AnonMoos (talk) 13:12, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Actually when the Germans reoccupied the Rhineland, the French Army vastly outnumbered the Germans. Why the French didn't stop them is a question that puzzled Shirer in his Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Hitler was a master when it came to bluffing nations, but in this case there was really no excuse save that the French were war-weary after the senseless abbatoir of WWI.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 15:45, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Ever seen Paths of Glory? It isn't hard to see why people would not want to fight for such an army, even against the Nazis. (What I don't understand is how much more extreme practices in the ancient world were tolerated) Wnt (talk) 19:26, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- 1914-1918 was "the ancient world"?!!!--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 19:30, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- France was part of the winning coalition in the Crimean War.

Sleigh (talk) 18:06, 1 November 2010 (UTC)

- France was part of the winning coalition in the Crimean War.

- 1914-1918 was "the ancient world"?!!!--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 19:30, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Ever seen Paths of Glory? It isn't hard to see why people would not want to fight for such an army, even against the Nazis. (What I don't understand is how much more extreme practices in the ancient world were tolerated) Wnt (talk) 19:26, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Actually when the Germans reoccupied the Rhineland, the French Army vastly outnumbered the Germans. Why the French didn't stop them is a question that puzzled Shirer in his Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Hitler was a master when it came to bluffing nations, but in this case there was really no excuse save that the French were war-weary after the senseless abbatoir of WWI.--Jeanne Boleyn (talk) 15:45, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's not really just the fact that France was defeated by Germany which by itself leads to all the jokes (such as the trees along the Champs-Élysées being planted so that the German army can march in the shade etc.); it's the way that the French army seemed to fold like a house of cards in both 1870 and May 1940, despite the fact that on paper it would seem that the military forces of the two nations should have been roughly comparable in strength. AnonMoos (talk) 13:12, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

The authors of the bible[edit]

From an aetheist point of view, where did the content of the bible come from? Are the authors functioning as a) reporters of events they saw themselves, b) recorders of what they have been told by others or of oral traditional stories, or c) inventing it as they write?

As I anticipate that the answer may be "all of those things", then what about the story of Moses and the Ten Commandments for example? Was there a real Moses who made the tablets? Thanks 92.15.25.142 (talk) 16:46, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Speaking from the scholarly historical point of view (not specifically as an atheist), there were almost certainly no relevant written records until after 1000 B.C, so everything in the Bible which refers to things happening before ca. 1000 B.C. (including the Pentateuch, Joshua, and Judges) comes from oral traditions. AnonMoos (talk) 16:52, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Our article History and the Bible is one article that discusses your first paragraph's questions. On whether there was a real Moses, our article Moses has a "Historicity" section that discusses the likelihood that Moses was real. Comet Tuttle (talk) 16:53, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The Straight Dope did a good series of articles on the authorship of the Bible. See also Authorship of the Bible. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 16:56, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's perhaps worth noting that you don't have to be an atheist to question the historical accuracy of the Bible, or to consider its human sources. (Though, to be clear, I am one myself). AndrewWTaylor (talk) 17:02, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Agreed. I am a Catholic, but I still ask these questions. Aaronite (talk) 17:35, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Note that most of our discussions on this topic, such as the discussion of the historicity of Moses and authorship of the Bible, (probably appropriately) give attention to the views of Biblical scholars and Biblical historians. It is important to remember, particularly if you are not a believer, that many or most Biblical historians and scholars are believers and may have an interest in arguing that Biblical texts have a historical basis. For example, if you are an atheist, it may not carry much weight for you if most "Biblical historians" reject the idea that Moses might be fictional. Starting from a different set of premises and biases, it may be entirely plausible that Moses is a fictional character. Marco polo (talk) 17:38, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Well, Marco, you do need to distinguish between types of scholarship here. Academic scholars in religious studies (of which there are many) take the historicity of religious stories as an open question, and for the most part assume that detailed figures have some historical basis (while some of the more schematic figures are assumed to be pure archetypes). The only real conflicts over historicity come from people who are either defending or attacking a religious perspective (text A being historically true/false <=> religion B being false/true). The general academic consensus about the content of the bible is that the new testament was written down by the apostles or their followers many years after Jesus died (assuming he was a historical figure), and that they were gathered together a few centuries later (in a heavily edited and contested fashion), along with written versions of Hebrew oral tradition as the old testament, to form the first version of the Christian bible. --Ludwigs2 18:02, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Note that most of our discussions on this topic, such as the discussion of the historicity of Moses and authorship of the Bible, (probably appropriately) give attention to the views of Biblical scholars and Biblical historians. It is important to remember, particularly if you are not a believer, that many or most Biblical historians and scholars are believers and may have an interest in arguing that Biblical texts have a historical basis. For example, if you are an atheist, it may not carry much weight for you if most "Biblical historians" reject the idea that Moses might be fictional. Starting from a different set of premises and biases, it may be entirely plausible that Moses is a fictional character. Marco polo (talk) 17:38, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Agreed. I am a Catholic, but I still ask these questions. Aaronite (talk) 17:35, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's perhaps worth noting that you don't have to be an atheist to question the historical accuracy of the Bible, or to consider its human sources. (Though, to be clear, I am one myself). AndrewWTaylor (talk) 17:02, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Anyway, in the absence of documentary evidence of Moses's existence—apart from the accounts in the Bible, first written several centuries after Moses is supposed to have lived—we simply can't know whether a person really lived who was named Moses or was the real-life basis of the character named Moses. Any arguments about the historicity of Moses by religious or nonreligious scholars are just speculative guesses. Marco polo (talk) 19:50, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- I find it remarkable that so little is known about John Frum, even though the religion worshiping him is so young that he could theoretically still be alive. It seems possible that no single founding person existed at all, by that or any other name. -- BenRG (talk) 02:36, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- We know rather more about the person revered by the Prince Philip Movement. DuncanHill (talk) 12:33, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- I find it remarkable that so little is known about John Frum, even though the religion worshiping him is so young that he could theoretically still be alive. It seems possible that no single founding person existed at all, by that or any other name. -- BenRG (talk) 02:36, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Where are the original texts? Are they online? If not, why not? Zoonoses (talk) 20:20, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- What do you mean by the "original texts"? I mean, it becomes a rather complicated question. If you think that the King James Bible is the "derivative" version, then you look and find it is a translation of the Vulgate, which itself is a collection of translation of other texts, and so on. Sometimes we find things like the Dead Sea Scrolls which give us (often somewhat varying) "original" (very old) editions of said translated works. But it's not a trivial thing to say which are the "original texts." In general there are times when groups have said "this is the canon", but over the course of both Judaism and Christianity, definitions of what is canon have varied quite a bit. Even when the canon is itself very old (like the Masoretic Text) it is always comprised of a combination of earlier "original texts", some of which we have today, some of which we don't. The term "Bible" is actually quite indicative of this nature of things — it is literally a book of books, a collection of different testaments that have been passed down over the years, largely in an oral tradition, later in a written tradition, that have been collected and are now regarded as a single document despite their often quite disparate origins. Many of these things are online, in any case. --Mr.98 (talk) 22:03, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Basic Greek and Hebrew Biblical texts are certainly on-line, but to receive the full benefits of scholarship, you'll probably need to consult the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia Old Testament and the Nestle-Aland New Testament editions... AnonMoos (talk) 22:48, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The Codex Sinaiticus is in the British Museus, while the Isaiah scroll is in the Shrine of the Book in Israel (to mention two prominent early Biblical manuscripts). AnonMoos (talk) 12:23, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

I immersed myself in the New Testament academic research. Somehow my faith as a Christian is stronger b/c believing in the Bible as magically written was difficult. Most otherwise educated Christians are threatened by the academic work. I am akin to a heretic for reading works of fiction as fiction, such as The Last Testament of Christ. It annoys me. My personal experience is that Anglican priests will discuss the work with me but won't address the larger parish.75Janice (talk) 21:28, 28 October 2010 (UTC)75Janice

To provide an example of a point made above, academic scholar Amy-Jill Levine is an Orthodox Jew who regards Moses and King David as non-historical. For her, there's no contradiction. Unless you're a fundamentalist, one doesn't need to believe in the literal historical accuracy of the Old or New Testaments to be an adherent of those religions. —Kevin Myers 00:34, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- The tradition of the historical authority of the Pentateuch derives from the historical authority of the Books of Kings and the Books of Chronicles, which were indeed written long after the events took place. One mustn't forget the records that were available to Jeremiah and Ezra that are no longer available to us. schyler (talk) 00:54, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

Marriage in the three Abrahamic religions[edit]

Is a marriage ceremony in any one of the three Abrahamic religions recognised as valid by the two other religions? Or would the other religions consider that the couple were unmarried and their children illegitimate? 92.15.25.142 (talk) 20:05, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- The Catholic church certainly hasn't adopted an exclusivist position, and the traditional Muslim answer was the "millet" system... AnonMoos (talk) 22:43, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Millet (Ottoman Empire) 92.28.244.197 (talk) 14:05, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Jesus' command at Mark 12:17 commands Christians to obey human government. This would include the recognition of Common-law marriage. schyler (talk) 22:52, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Religions recognize common law marriage? That seems unlikely; it's impossible enough to get that recognized by a civil law country, why would a church recognize it? Adam Bishop (talk) 23:26, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

Judaism doesn't try to regulate other religions. From a perspective of Jewish law, it doesn't matter if Christians or Muslims are married or unmarried. I can think of one possible complication: Let's say a Christian gets married, then, without getting divorced, converts to Judaism and tries to marry a Jew. Is that OK? Almost all branches of Judaism now prohibit polygamy, so if the convert is still married, you can't marry him or her. But if Judaism doesn't recognize the Christian marriage, does it matter? I don't know the answer to that question, and with the ease of getting divorces nowadays, I don't think it's much of an issue. Of course only marriages and divorces conducted under Jewish law are valid for Jewish religious purposes. -- Mwalcoff (talk) 00:34, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Nice evaluation and nafka mina. In fact, Judaism does regulate the behavior of all humans, even though most gentiles are probably unaware or would consider such a concern irrelevent. Judaism maintains that there are no other religions, and so all gentiles are grouped as one large group, despite any supposed allegiance of a gentile to Hinduism, Calvinism, etc, and all gentiles are (according to Jewish law) bound by the Noachide laws, the fourth of which prohibits adultery. If Judaism didn't consider gentile marriage, how could such a prohibition exist? So according to Jewish law, any male and female gentile who consider themselves to be a couple, whether or not they have a signed and notarized document from a priest, judge or municipal witch doctor is considered a couple, until such time that they no longer consider themselves a couple. Of course, such a definition necessitates a thorough review of all parameters, such as unilateral disengagement from the union, etc. Be that as it may, Judaism does consider any Christian or Muslim male/female couple who consider themselves a couple to be married. This includes a guy and girl who live together and may or may not have children, even if they have no legal or religious contract because such institutions are not necessary (government) or not recognized (religion) in terms of marriage. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 19:28, 31 October 2010 (UTC)

- Adam: maybe I am just not too well-versed in law; what I mean is that Christians (distinct from The Church) recognize and respect civil authority. schyler (talk) 00:48, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

There are six relationships between the three religions. Christianity probably recognises the other two's marriage ceremonies. I'm unclear about the other four relationships. I was asking because of this news story: http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5j3T0tngz5-ny7yuDobauqv8msNxQ?docId=CNG.70d49186605692c667f186f852b87f44.2d1 - are Christian married couples unmarried from Islam's point of view? 92.28.244.197 (talk) 14:10, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

Other notions of good and evil[edit]

This article http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/1985/who-wrote-the-bible-part-1 makes an interesting point at the end: "Our notions of good and evil, of history as a linear process, of the relationship between the individual and morality, of the dignity of man ("created in the image of God"), all stem from this seminal work. The pagan nations....did not see anything wrong with mistreatment of animals, with leaving unwanted babies out in the woods, with working slaves without relief."

Are there any cultures in the world today that have very different notions of good and evil than that of the Abrahamic religions, not just variations in the details? (Space aliens when and if we meet any may not share our notions of good and evil). 92.15.25.142 (talk) 20:15, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- I dispute all those claims and can spout the obvious counter: Many Christians have not seen anything wrong with mistreatment of animals, leaving unwanted babies out in the woods, and working slaves without relief; and may pagan nations have seen all those things as wrong. What nonsense. Unfortunately our article Morality without religion is very short; and Secular ethics is pretty scattered. Comet Tuttle (talk) 20:45, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- And even the example of cutting off the hand of a thief is something that Christian nations in the past surely did, the Bible does not prohibit, and some areas of Abrahamic tradition (particularly Sharia law) still actively encourages today. Even within the Abrahamic religions you have deep, deep differences amongst groups, sects, and different time periods regarding morality on this level, much less between them. Heck, there are a lot of people today even within thoroughly Westernized, comparatively homogenized moral views who would deeply disagree as to whether the Ten Commandments are good ideas or not. (I think the aspects about having one god, not making idols, etc. are completely discretionary; honoring the parents is a nice idea but not mandatory; not murdering is important; adulterating is a recipe for marital strife but none of my business; not stealing is important but sometimes hard to pin down; false perjuring is probably immoral; and anything about coveting is totally fine because coveting is not the same thing as doing). There are lots of anthropological accounts of people thinking all sorts of things are morally fine (e.g. cannibalism, infanticide) that we would disagree with. --Mr.98 (talk) 22:13, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- By the Torah not permitting cutting the hand off a thief, it prohibits it -- the punishment for stealing is monetary in nature unless a human is stolen (kidnapping). Where do you see otherwise? DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 19:31, 31 October 2010 (UTC)

- Sorry, but it's not a Christian religious punishment, and I would be quite surprised if it was a common punishment at any time in European history. AnonMoos (talk) 04:54, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- You are talking about a society that is very different to that today. Corporeal punishment and mutilation were not uncommon for crimes which did not warrant hanging. Googlemeister (talk) 12:56, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- You're right: according to mutilation, Christians mainly went for the ears. There was also a fair amount of human branding. I suppose the relevant question, though, is not whether Christians avoided doing those things, but whether the concept of "inhumane" was first introduced or substantially popularized by the bible, and unknown to pagans. 81.131.53.127 (talk) 13:23, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Cutting off a hand was a punishment for theft in medieval law; cutting off a foot, a nose, an ear, an eye, branding, whipping, and execution were also punishments. But those come from Roman and Germanic law, not Catholic canon law, which doesn't have any punishment involving bloodshed (well...execution sometimes). Adam Bishop (talk) 14:03, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Have you got a cite for those hand or foot removals? I thought it was true as well, but then, I think all kinds of things which turn out to be wrong, and after trawling through various wikipedia articles I couldn't find any references to western medieval societies cutting off anything other than ears (unless we count execution by dismemberment). Of course, the question of whether Catholic law, or Christianity, encourages or prohibits the cutting off of anything, is not the original question: the real question is whether the idea of inhumanity is something we owe to Christianity, or whether it's likely to be independently arrived at by multiple cultures. 81.131.53.127 (talk) 14:45, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Byzantine law has lots of mutilations for punishment. For feet I was thinking of the Council of Nablus where that is one of the possible punishments for theft. I am mostly familiar with crusader and Byzantine stuff, but Western Europe has lots of similar laws. I can't think of a specific citation for cutting off hands and feet but it should be easy enough to find one, I'll have to dig a little. Adam Bishop (talk) 19:30, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Have you got a cite for those hand or foot removals? I thought it was true as well, but then, I think all kinds of things which turn out to be wrong, and after trawling through various wikipedia articles I couldn't find any references to western medieval societies cutting off anything other than ears (unless we count execution by dismemberment). Of course, the question of whether Catholic law, or Christianity, encourages or prohibits the cutting off of anything, is not the original question: the real question is whether the idea of inhumanity is something we owe to Christianity, or whether it's likely to be independently arrived at by multiple cultures. 81.131.53.127 (talk) 14:45, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Cutting off a hand was a punishment for theft in medieval law; cutting off a foot, a nose, an ear, an eye, branding, whipping, and execution were also punishments. But those come from Roman and Germanic law, not Catholic canon law, which doesn't have any punishment involving bloodshed (well...execution sometimes). Adam Bishop (talk) 14:03, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- And even the example of cutting off the hand of a thief is something that Christian nations in the past surely did, the Bible does not prohibit, and some areas of Abrahamic tradition (particularly Sharia law) still actively encourages today. Even within the Abrahamic religions you have deep, deep differences amongst groups, sects, and different time periods regarding morality on this level, much less between them. Heck, there are a lot of people today even within thoroughly Westernized, comparatively homogenized moral views who would deeply disagree as to whether the Ten Commandments are good ideas or not. (I think the aspects about having one god, not making idols, etc. are completely discretionary; honoring the parents is a nice idea but not mandatory; not murdering is important; adulterating is a recipe for marital strife but none of my business; not stealing is important but sometimes hard to pin down; false perjuring is probably immoral; and anything about coveting is totally fine because coveting is not the same thing as doing). There are lots of anthropological accounts of people thinking all sorts of things are morally fine (e.g. cannibalism, infanticide) that we would disagree with. --Mr.98 (talk) 22:13, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Like Mr. 98 is saying, even in one culture and within Christianity and other Abrahamic religions itself there are wide variations on the notions of good and evil, or right and wrong. A Lutheran will not do an altar call but an Evangelical might. Jehovah's Witnesses do not celebrate Christmas because of the origins of it's practices, but any other Christian may. It is all an attempt at discovering Truth, which one must decide if it exists at all. If they decide against the existence of this Form, then they must align themselves with something, even unwittingly, and it is most likely that of Thrasymachus who was influential to Relativists. schyler (talk) 22:48, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

To answer the OP's question, there are probably still war-like tribes in remote parts of South America or Papua New Guinea where not only is it OK to kill an enemy, but its prestigeous to have done so. In the recent past, the Nazis. I note that the common assumption is that space aliens will be similar to us in morality, but just have different bodies, but there's no reason to suppose this. Someone here was shocked how other chickens attacked another chicken with some blood on it, but its foolish to assume that other species have Abrahamic notions of good and evil. 92.28.244.197 (talk) 14:19, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

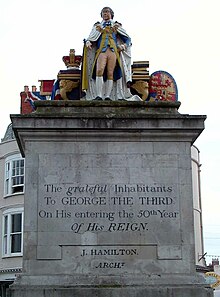

Statue of George III in Weymouth[edit]

There is a statue of George III in Weymouth, erected by a grateful population. The statue itself is freshly painted, and the inscription on the front of the pedestal clear and easy to read. On the back of the pedestal is a longer inscription, much eroded by the passage of time. Does anyone have the text of the eroded inscription? Thanks, DuncanHill (talk) 20:37, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- This description states that the legible parts of the inscription were transcribed onto a small plaque placed at the foot of the front of the plinth:

"Amongst other information is the date (18 October 1809) of a general meeting, with James Bower, Mayor, in the chair, at which various resolutions were passed, including 'A congratulatory address...' and 'That Public Dinners and general illuminations are ill adapted to this occasion or the awful times in which we live....' Instead, a public subscription would be raised, partly '....to contribute to the comfort of our Poorer Brethren .....and Prisoners of War....' half of the proceeds to each of these worthy causes. In addition 'That (sundry named persons) being possessed of a statue of our excellent king... offered to present it..' A separate subscription would be raised for this, and the committee given full powers to find a site and erect it. The lettering is all splendidly set out and incised, and, like the principal inscription, is painted black."

- Ghmyrtle (talk) 22:36, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- Many thanks - have only ever seen it from the coach, haven't had a chance to inspect it closely. DuncanHill (talk) 22:41, 28 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's interesting that the good folk of Weymouth thought of George III as "our excellent king". Historians on the whole have been less generous in their judgements. Alansplodge (talk) 15:47, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- You might be interested in this article. Ghmyrtle (talk) 16:03, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- It's interesting that the good folk of Weymouth thought of George III as "our excellent king". Historians on the whole have been less generous in their judgements. Alansplodge (talk) 15:47, 29 October 2010 (UTC)

- Probably a statement of defiance of Napoleon, really. 81.131.60.13 (talk) 04:56, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Historians may have been ungenerous in their assessment of George III (though I suspect American historians have been more unkind than British ones) - but he was a popular king, seen as a good family man and father, never took a mistress, born and raised in England ("What, tho' a boy! It may with truth be said, A boy in England born, in England bred"), and a patriot ("We are here in daily expectation that Bonaparte will attempt his threatened invasion ... Should his troops effect a landing, I shall certainly put myself at the head of mine, and my other armed subjects, to repel them."). DuncanHill (talk) 09:32, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- My impression of English royalty, from the time when they had actual power, is that they were almost without exception very bad people. I don't think George was worse than the general run of them, but that's hardly praise. That's why I'm to some extent an admirer of Oliver Cromwell, even though I'm sure I wouldn't have liked to live under his rule — at least he did something about that line of brutal thugs. --Trovatore (talk) 09:48, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Cromwell was a brutal thug, Charles I was not, and nor were many of his predecessors. Frankly, I find it hard to see how anyone could admire Cromwell, who, quite apart from his mass-murder of Irish people (for which we are still paying the price today), was a religious bigot and military dictator. I suppose that if you hate Catholics, the Irish, Christmas, beautiful churches, and the rule of parliament, you might well think Cromwell was acceptable, but otherwise, no, he was vile. He did one, and only one, good thing in his reign. DuncanHill (talk) 09:59, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Charles might not have been a thug, but Henry VIII was, and Elizabeth I was, and Mary I was, and I could go on except I'd have to look stuff up. I certainly don't hate Catholics. Don't have much use for kings, though. --Trovatore (talk) 10:04, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Many of us have less time for fanatical military dictators. The bells of my local parish church were rung for 3 full days when the monarchy was restored. Alansplodge (talk) 15:09, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- The original kings, as far as I can tell, were military dictators. Then they managed to pass the office on to their kids, and convince folks that they'd been installed in that position by God. Charles I's tragedy was that he apparently believed it himself, and this seems to have let him behave tranquilly as a kleptocrat. Granted, when you have a true believer in charge convinced of his cause, you may very well long for the days of kleptocrats, but that doesn't make them a good thing. --Trovatore (talk) 20:10, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Not sure what the point of calling Elizabeth I a "thug" is; she insisted on many of the royal prerogatives as these were commonly understood in European monarchies at the time, but she was not especially tyrannical or brutal according to the standards of the period, and she skilfully steered England's foreign policies through many dangers which could have had severe negative consequences for England, while providing peaceful stability at home, and overseeing the abolition of serfdom and first beginnings of "welfare" protections. She didn't execute people for heresy, but for treason -- at a time when her enemies were openly and shamelessly advocating and promoting treason in England (see An Admonition to the nobility and people of England, Regnans in Excelsis etc.).

- Many of us have less time for fanatical military dictators. The bells of my local parish church were rung for 3 full days when the monarchy was restored. Alansplodge (talk) 15:09, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Charles might not have been a thug, but Henry VIII was, and Elizabeth I was, and Mary I was, and I could go on except I'd have to look stuff up. I certainly don't hate Catholics. Don't have much use for kings, though. --Trovatore (talk) 10:04, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Cromwell was a brutal thug, Charles I was not, and nor were many of his predecessors. Frankly, I find it hard to see how anyone could admire Cromwell, who, quite apart from his mass-murder of Irish people (for which we are still paying the price today), was a religious bigot and military dictator. I suppose that if you hate Catholics, the Irish, Christmas, beautiful churches, and the rule of parliament, you might well think Cromwell was acceptable, but otherwise, no, he was vile. He did one, and only one, good thing in his reign. DuncanHill (talk) 09:59, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- My impression of English royalty, from the time when they had actual power, is that they were almost without exception very bad people. I don't think George was worse than the general run of them, but that's hardly praise. That's why I'm to some extent an admirer of Oliver Cromwell, even though I'm sure I wouldn't have liked to live under his rule — at least he did something about that line of brutal thugs. --Trovatore (talk) 09:48, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Historians may have been ungenerous in their assessment of George III (though I suspect American historians have been more unkind than British ones) - but he was a popular king, seen as a good family man and father, never took a mistress, born and raised in England ("What, tho' a boy! It may with truth be said, A boy in England born, in England bred"), and a patriot ("We are here in daily expectation that Bonaparte will attempt his threatened invasion ... Should his troops effect a landing, I shall certainly put myself at the head of mine, and my other armed subjects, to repel them."). DuncanHill (talk) 09:32, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- Probably a statement of defiance of Napoleon, really. 81.131.60.13 (talk) 04:56, 30 October 2010 (UTC)

- By the way, the reason George III isn't remembered fondly in the U.S. is that he adopted an attitude from beginning to end of refusing to recognize that the British colonial inhabitants of North America had any legitimate grievances, and also manipulated the ministries so that politicians hostile to American aspirations would be in power in Britain. On the political level, the colonists were demanding at a minimum either direct representation in the British parliament, or some kind of entrenched "constitutional" guarantees and protections that couldn't be overturned in the future by a simple majority vote of parliament. If George III had ever seriously considered either of these ideas, then he might be remembered differently in the U.S... AnonMoos (talk) 13:03, 1 November 2010 (UTC)