User talk:Khodabandeh14/Safavids/OfficalNameOrigin

Some points on Safavids which users keep repeating and summarized here: [3]

Moved from mainspace

This points concerns the Safavid article. There are four issues that keep constantly coming from what I believe are users who push POV.

- Reponse to a persistent false claim by a user that the name Iran was not used officially. I had discussed this point 10x but the user simply ignored it, and repeated his own argument which had no RS source.

- On the dispute origin of Safavids and why it probably should not be in the lead, and why the Kurdish origin is stronger.

- Claim on the official language of the Safavids empire.

- Trivial claims about alphabets for the intro and ethnonyms. Was the term "Azerbaijani" used as a term in Safavid era? No. Then why are users who make a fuss about "official names" and false claim "Iran was not used" pushing POV? Why are they trying to get rid of the word Iran from the artice? Wikipedia doesn't care about official names to begin with, it cares about most frequent terms. However as shown below, source exists that consider the official name Iran (note other names might have existed as well since there was no UN and no single set of standards at the time).

Suggestions for the current intro[edit]

- I believe the origin should state only that it is shrouded in mystery (per Encyclopaedia of Islam article on Safavids) and detail discussion should be in the body.

- The latin Azeri script I do not care about it, but it is anachronism (see Section 5) and unprovable in terms of the phonetic vowels it is written in.

On the name Iran/Persia being used officially[edit]

Secondary sources showing Iran used officially with one explicitly stating it[edit]

The users who ignore these sources (I believe due to racism). Here I am not concerned with the profuse use of Iran as an ethno-cultural designation prior to Safavids. This has been discussed here:

- Tons of Google books sources use it: A) [4] (Safavid Persian Empire) B) [5] (Safavid Iran) (note the tile of the book: "Safavid Iran: rebirth of a Persian empire" by Andrew J. Newman C) Tons of google books use: "Safavid Persia" [6] D) Tons of google books use "Safavid empire of Persia" [7]

- So terms like "Safavid Persia", "Safavid Persian empire", "Safavid Iranain empire" and etc. are completely valid.

- Further evidence of a desire to follow in the line of Turkmen rulers is Ismail's assumption of the title "Padishah-i-Iran", previously held by Uzun Hasan. (H.R. Roemer, The Safavid Period, in Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. VI, Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 339).

- Alireza Shapur Shahbazi (2005), "The History of the Idea of Iran”, in Vesta Curtis ed., Birth of the Persian Empire, IB Tauris, London, p. 108: "Similarly the collapse of Sassanian Eranshahr in AD 650 did not end Iranians' national idea.The name "Iran" disappeared from official records of the Saffarids, Samanids, Buyids, Saljuqs and their successor. But one unofficially used the name Iran, Eranshahr, and similar national designations, particularly Mamalek-e Iran or "Iranian lands", which exactly translated the old Avestan term Ariyanam Daihunam. On the other hand, when the Safavids (not Reza Shah, as is popularly assumed) revived a national state officially known as Iran, bureaucratic usage in the Ottoman empire and even Iran itself could still refer to it by other descriptive and traditional appellations". (see below for Academic background).

- A.A. Ashraf, "Iranian identity iii. Medieval Islamic period" in Encyclopedia Iranica[8]:

- Excerpt 1: "The Safavid kings called themselves, among other appellations, the “heart of the shrine of ʿAli” (kalb-e āstān-e ʿAli), while assuming the title of Šāhanšāh (the king of kings) of Persia/Iran".

- Excerpt 2: "Even Ottoman sultans, when addressing the Āq Quyunlu and Safavid kings, used such titles as the “king of Iranian lands” or the “sultan of the lands of Iran” or “the king of kings of Iran, the lord of the Persians” or the “holders of the glory of Jamšid and the vision of Faridun and the wisdom of Dārā.” They addressed Shah Esmaʿil as: “the king of Persian lands and the heir to Jamšid and Kay-ḵosrow” (Navāʾi, pp. 578, 700–2, 707). During Shah ʿAbbās’s reign (q.v.) the transformation is complete and Shiʿite Iran comes to face the two adjacent Sunni powers: the Ottoman Empire to the west and the Kingdom of Uzbeks to the east."

- Excerpt 3: "“Iran” in Safavid historiography. Ḡiāṯ-al-Din Ḵᵛānda-mir (d. 1524), the first prominent Safavid historian, was one of the last historians of the Il-khanid-Timurid era and the grandson of Mir Moḥamamd Mirḵᵛānd, author of the influential history, Rawżat al-sÂafā. In preparing his general history, Ḥabib al-siar fi aḵbār afrād al-bašar, Ḵᵛāndamir followed the style of Rawżat al-sÂafā and that of such popular historical works as Neẓām al-tawārikò and Tāriḵ-e gozida (see above). The frequency of the usage of Iran, Irānzamin and related terms in the three volumes of Ḥabib al-siar (completed in 1524) reveals the evolution in the usage of these terms in the Islamic era. The frequency is relatively high in volume I, with 28 references to events of the pre-Islamic period; it drops sharply to 12 in volume II, treating the history of the Islamic period up to the Mongol era; and it leaps to 69 references in volume III, dealing with the Il-khanid-Timurid, and early Safavid periods. Other representative works of this period also make frequent references to “Iran,” including ʿĀlamārā-ye Šāh Esmāʿil, ʿĀlamārā-ye Šah Ṭahmāsp, Ḥasan Beg Rumlu’s (d. 1577) Aḥsan al-tawāriḵ, Ebn Karbalāʾi’s (d. 1589) Rawżāt al-jenān, Malekšāh Ḥosayn Sistāni’s (d. 1619) Eḥyāʾ al-moluk, Mollā ʿAb-al-Nabi Faḵr-al-Zamāni’s Taḏkera-ye meyḵāna (1619); Eskander Beg Rumlu’s (d. 1629) Aḥsan al-tawāriḵ; Wāleh Eṣfahāni’s (d. 1648) Ḵold-e barin, Naṣiri’s (d. 1698) Dastur-e šahriārān. Finally, Moḥammad Mofid Bāfqi (d. 1679), in addition to making numerous references to “Iran” and “ʿAjam” in his Jāmeʿ-e Mofidi (q.v.), refers to distinct borders of Iran and its neighbors, India, Turān, and Byzantium as well as the influx of people from those lands to Iran. In a number of cases, he describes the nostalgia of those Iranians who migrated to India but were later compelled to return by their love for their homeland (ḥobb al-waṭan; see below). He makes a number of insightful comments about Iranian identity and various features of the lands of Iran in his historical geography of Iran, Moḵtaṣar-e Mofid. Adopting the model of Mostawfi’s Nozhat al-qolub, he makes some 20 references to Iran, Irānzamin, and Irānšahr, as well as the borders of Iran’s territory, in the introduction to his work. He makes numerous references, furthermore, to Persian mythological and legendary figures in the traditional history of Iran as founders of a large number of cities in Yazd, Iraq, Fārs, Azerbaijan, and other parts of Iran. Finally, he provides readers with a useful list of Iranian islands in the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman. On average, on 62 occasions the term Iran and related concepts were used in each of the above historical works of the Safavid era."

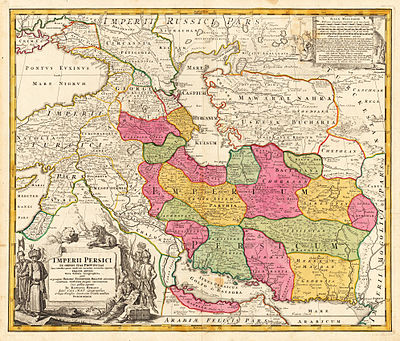

Map of Persia[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- The name Iran continued to the Safavid era and the Safavid like the previous empires and people inhabiting the land Iran, used the same geographical designation. By now though, there was a government which had unified Iran into a powerful state. For example the Safavid book, 'Alem Araayeh Abbasi has used the name Iran/Iranians 73 times for the land and the people of Iran[1].

- For example a sample letter of Shah Abbas to Jalal al-Din Akbar[2]:

| “ | و چون خاطر عاطر پادشاهی عالم پناهی متوجه تفحص حالات ایران...بدین جهت...شرح مجملی از حالات .. مصدع ملازمان رفیع مقام عالیشان میگردد | ” |

- The book Monšaʾāt al-salāṭīn compiled by Fereydun Ahmbed Beg[9] which contains these letters has been published in Istanbul. Here I will quote from the 2nd edition the pages that use the title "IranShahi (Royal Kingdom of Iran or King of Iran) [3]:

فریدون بیگ، منشآت السلاطین،چاپ دوم، استانبول، 1275 هجری قمری Volume 1: Pages with regards to Shah Esmail using Iran-Shahi Shah Esmail (345) Volume 2: Pages with regards to ShahTahmasp using Iran-Shahi Shah Tahmasp (38, 42,43..) Pages with regards to Shah Abbas using Iran-Shahi Shah Abbas (252, 254, 257,261) Pages with regards to Shah Abbas using Iran-PadeShahi Shah Abbas (249) Pages with regards to Shah Khodabandeh using Iran-Shahi Shah Khodabandeh(283) Pages with regards to Shah Safi using Iran-Shahi Shah Safi(299,301,317..)

Origin[edit]

Secondary Sources and primary sources[edit]

The Safavid identity is disputed as noted by Savory. It is complex and should not be in the introduction with the exception of possible fact: "The Safavid origin is not clear". Note origin in the Islamic historigraphy sense means fatherline of the dynasty. The last Safavid Shahs were parimarily Georgian through their mothers while the beginning Safavid Shahs had Turkoman/Greek mothers. However, origin of a dynasty in the Islamic historiography sense is not defined by wives but their father-line genealogy.

- Minorsky, V (2009), "Adgharbaydjan (Azarbaydjan", in Berman, P; Bianquis, Th; Bosworth, CE et al., Encyclopedia of Islam (2nd ed.), NL: Brill, http://www.encislam.brill.nl/, "After 907/1502, Adharbayjan became the chielf bulwark and rallying ground of the Safawids, themselves natives of Ardabil and originally speaking the local Iranian dialect"

- Roger M. Savory. "Safavids" in Peter Burke, Irfan Habib, Halil İnalcık: History of Humanity-Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, Taylor & Francis. 1999, p. 259: "From the evidence available at the present time, it is certain that the Safavid family was of indigineous Iranian stock, and not of Turkish ancestry as it is sometimes claimed. It is probable that the family originated in Persian Kurdistan, and later moved to Azerbaijan, where they adopted the Azari form of Turkish spoken there, and eventually settled in the small town of Ardabil sometimes during the eleventh century."

The oldest extant book on the genealogy of the Safavid family and the only one that is pre-1501 is titled "Safvat as-Safa"[4] and was written by Ibn Bazzaz, a disciple of Sheikh Sadr-al-Din Ardabili, the son of the Sheikh Safi ad-din Ardabili. There are only two pre-1501 (before the Safavids came to power) manuscripts of this work. According Ibn Bazzaz, the Sheikh was a descendant of a noble Kurdish man named Firuz Shah Zarin Kolah the Kurd of Sanjan[5]. The male lineage of the Safavid family given by the oldest manuscript of the Safwat as-Safa is:"(Shaykh) Safi al-Din Abul-Fatah Ishaaq the son of Al-Shaykh Amin al-din Jebrail the son of al-Saaleh Qutb al-Din Abu Bakr the son of Salaah al-Din Rashid the son of Muhammad al-Hafiz al-Kalaam Allah the son of ‘avaad the son of Birooz al-Kurdi al-Sanjani (Piruz Shah Zarin Kolah the Kurd of Sanjan)"[5]. The Safavids, in order to further legitimize their power in the Shi'ite Muslim world, claimed descent from the prophet Muhammad[4] and revised Ibn Bazzaz's work [4][6], obscuring the Kurdish origins of the Safavid family[4]

There seems to exist a consensus among Safavid scholars that Safavids originated in Iranian Kurdistan and moved to Iranian Azerbaijan, settling in Ardabil in the 11th century[5]. Accordingly, these scholars have considered the Safavids to be of Kurdish descent based on the origins of Sheykh Safi al-Din and that the Safavids were originally a Iranic speaking clan [5][7][8][9][10][11][4] [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19].

How did Safavids see themselves[edit]

- Safavids tried to base their legitimacy based on being descendant of the Imams. It is true that some Safavids had Georgian, Turkoman and others (Shah Abbas mother is said to be a Seyyed family or Georgian or Tajik) but in terms of Islamic dynasties, the dynasty saw itself as through its male lineage.

- "This official version contains textual changes designed to obscure the Kurdish origins of the Safavid family and to vindicate their claim to descent from the Imams"[4].

- F. Daftary, "Intellectual Traditions in Islam", I.B.Tauris, 2001. pg 147: "Apparently the first Safawid to add the title 'Sayyid' to his name was the son of Shah Ismai'l, Shaykh Hayar....But the origins of the family of Shaykh Safi al-Din go back not to Hijaz but to Kurdistan, from where, seven generations before him, Firuz Shah Zarin-kulah had migrated to Adharbayjan" [10]

Thus the Safavids saw themselves as descendants of the prophet of Islam. They did not have a geneology going back to Oghuz-Khans (hence Turcomans/Turks).

Attitude towards their Turcoman followers[edit]

Safavids specially Shahs Tahmasp and Shah 'Abbas tried to weaken the Turcoman influence. This suggests again that they did not see themselves as ethno-nationalist Turcomans but descendants of the Prophet and Iranian kings.

- "The third important problem faced by Esmāʿīl after the establishment of the Safavid state was how to bridge the gap between the two major ethnic groups in that state: the qezelbāš Turkmans, the “men of the sword” of classical Islamic society whose military prowess had brought him to power, and the Persian elements, the “men of the pen,” who filled the ranks of the bureaucracy and the religious establishment in the Safavid state as they had done for centuries under previous rulers of Persia, be they Arabs, Turks, Mongols, or Turkmans. ... Esmāʿīl then appointed a Persian to this office, but this policy, in which Esmāʿīl persisted despite the overt resentment and hostility of the qezelbāš, was even less successful. Between 1508 and 1524, the year of Esmāʿīl’s death, the shah appointed five successive Persians to the office of wakīl. Of the five, the first died a year or so after his appointment, and one chronicle makes the significant statement that he “weakened the position of the Turks” (Ḵoršāh, fol. 453b). "(R. Savory, "ESMĀʿĪL I ṢAFAWĪ" in Encyclopaedia Iranica)

- "The question of the language used by Shah Ismail is not identical with that of his ‘’race’’ or ‘’nationality’’. His ancestry was mixed: one of his grandmothers was a Greek princess of Trebizond. Hinz, Aufstieg, 74, comes to the conclusion that the blood in his veins was chiefly non-Turkish. Alread, his son Shah Tahmasp began to get rid of his Turcoman praetorians." (V. Minorsky, The Poetry of Shah Ismail, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 10, No. 4. (1942), pp. 1053).

Languages and official language[edit]

- Roemer, H. R. (1986). "The Safavid Period". The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–350. ISBN 0-521-20094-6, p. 331: "Depressing though the condition in the country may have been at the time of the fall of Safavids, they cannot be allowed to overshadow the achievements of the dynasty, which was in many respects to prove essential factors in the development of Persia in modern times. These include the maintenance of Persian as the official language and of the present-day boundaries of the country, adherence to the Twelever Shi'i, the monarchical system, the planning and architectural features of the urban centers, the centralised administration of the state, the alliance of the Shi'i Ulama with the merchant bazaars, and the symbiosis of the Persian-speaking population with important non-Persian, especially Turkish speaking minorities".

- Rudi Matthee, "Safavids" in Encyclopædia Iranica, accessed on April 4, 2010. "The Persian focus is also reflected in the fact that theological works also began to be composed in the Persian language and in that Persian verses replaced Arabic on the coins." "The political system that emerged under them had overlapping political and religious boundaries and a core language, Persian, which served as the literary tongue, and even began to replace Arabic as the vehicle for theological discourse".

- Ronald W Ferrier, The Arts of Persia. Yale University Press. 1989, p. 9.

- John R Perry, "Turkic-Iranian contacts", Encyclopædia Iranica, January 24, 2006: "…written Persian, the language of high literature and civil administration, remained virtually unaffected in status and content"

- Cyril Glassé (ed.), The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, revised ed., 2003, ISBN 0759101906, p. 392: "Shah Abbas moved his capital from Qazvin to Isfahan. His reigned marked the peak of Safavid dynasty's achievement in art, diplomacy, and commerce. It was probably around this time that the court, which originally spoke a Turkic language, began to use Persian"

- "Since the Safavids came from Persian Azarbaijan and Azarbaijan had adopted the Turki language in the years of their emergence (the language before Turki having been the ancient Iranian language Azari), they spoke both Turki and Persian, but since their soldiers were drawn from Turki speakers (and perhaps for other reasons as well) Turki became the court language of the Safavids; however all literary works of this period, wether poetry or prose, are in Persian, with the rare exception of certain poetry, notably that of Shah Isma'il, which is in Turki over the takhallus Khata'i." (George Morrison, History of Persian literature from the beginning of the Islamic period to the present day, vol.2 , Brill, 1981: 145).

Azerbaijani and Azerbaijani language[edit]

Classical Azeri[edit]

The Azeri-Turkish of the Safavid language had some major differences.

- "The hold of Persian as the chief literary language in Azerbaijan was broken, followed by the rejection of classical Azerbaijani, an artificial, heavily Iranized idiom that had long been in use along with Persian, though in a secondary position. This process of cultural change was initially supported by the tsarist authorities, who were anxious to neutralize the still-widespread Azerbaijani identification with Persia. In doing so, the Russians resorted to a policy familiar in other parts of the empire, where Lithuanians, for example, were sporadically encouraged to emancipate themselves from Polish cultural influences, as were the Latvians from German and the Finns from Swedish.( Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. p 29. ISBN: 0231070683)

- "A specific Turkic language was attested in Safavid Persia during the 16th and 17th centuries, a language that Europeans often called Persian Turkish ("Turc Agemi", "lingua turcica agemica"), which was a favourite language at the court and in the army because of the Turkic origins of the Safavid dynasty. The original name was just turki, and so a convenient name might be Turki-yi Acemi. This variety of Persian Turkish must have been also spoken in the Caucasian and Transcaucasian regions, which during the 16th century belonged to both the Ottomans and the Safavids, and were not fully integrated into the Safavid empire until 1606. Though that language might generally be identified as Middle Azerbaijanian, it's not yet possible to define exactly the limits of this language, both in linguistic and territorial respects. It was certainly not homogenous - maybe it was an Azerbaijanian-Ottoman mixed language, as Beltadze (1967:161) states for a translation of the gospels in Georgian script from the 18th century." (É. Á. Csató, B. Isaksson, C Jahani. Linguistic Convergence and Areal Diffusion: Case Studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, 2004, p. 228).

So no, this classical Azeri did not use the latin alphabet. However, I do not care about this issue.

Scholarly relavence[edit]

Note Savory, Minorsky and Mathee can be considered Safavid specialists. The others are Iranologist. We should always take Safavid scholars over general iranologist. Note this is not by any means a complete list of Safavid specialists, but only some prominent ones.

Vladimir Minorsky[edit]

See the article Vladimir Minorsky. Note his opinion on Safavids Iranian origin is given above per Encyclopaedia of Islam.

Roger Savory[edit]

Probably the most important scientist ever when it comes to Safavid history. He has written many books, and articles, as well as most of the primary books and articles on Safavids in Encyclopaedia of Islam and Encyclopaedia Iranica.

The study of Iranian history in the Timurid and Safavid periods has been particularly prominent in the Canadian academic tradition. Roger Savory, Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto, has had a profound influence on the study of the Safavid period (1501-1722). His numerous books and articles on Safavid political and military history, administration, bureaucracy, and diplomacy–translated into several languages–have done much to deepen our understanding of the period, particularly in the field of political and administrative history. Following in the footsteps of his eminent teacher Vladimir Minorsky at the School of Oriental and African Studies, Savory has worked meticulously on the complex structures of officialdom and bureaucracy in the 16th century (See “The Principal Offices of the Safawid State During the Reign of Isma¿il I (907-30/1501-24),” BSOAS 23, 1960, pp. 91-105, and “The Principal Offices of the Safawid State During the Reign of Tahmasp (930-84/1524-76),” BSOAS 24, 1961, pp. 65-85). He was the principal organizer of the first academic conference in Canada on Iran (“Iranian Civilization and Culture”, Dec. 10-11, 1971). The event and the ensuing publication of the proceedings (Iranian Civilization and Culture,Montreal, 1972) heralded Canada’s formal entry into the Iranian academic world. His Iran Under the Safavids (Cambridge, 1980), a survey of the rise of and fall of the Safavid dynasty, provided undergraduate and graduate students with a succinct introduction to this important dynasty. This was supplemented by Savory’s magnum opus, his translation of the monumental Safavid court chronicle, Eskandar Beg Monπi’s T˝rik˚-e ¿˝lam ˝r˝-ye ¿abb˝si as History of Shah ¿Abb˝s the Great (I-II, PHS, Boulder, Colorado, 1979; III (index), Bib.Pers., New York, 1986).

Alireza Shahpur Shahbazi[edit]

Professor since 1990) of History, Eastern Oregon University I. PUBLICATIONS: A. Book (see also D. Translation)

1. Cyrus the Great: Founder of the Persian Empire (Shiraz University Publication, No. 19, Shiraz 1970; awarded Book of the Year Prize, 1970). Second revised edition with an English version are in preparation. 2. Darius the Great (Shiraz University Publication, No. 26, Shiraz 1971), second revised version is in preparation. 3. A Persian Prince: Cyrus the Younger (Shiraz University Publication, No. 29, Shiraz 1971). 4. Illustrated Description of Naqš-i Rustam, (Tehran, 1978). Second revised edition in the press. 5. The Irano-Lycian Monuments: The Antiquities of Xanthos and Its Region as Evidence for the Iranian Aspects of the Achaemenid Lycia (Institute of Achaemenid Research Publication, No. II, Tehran 1975) [1973 Doctoral Thesis for London University]. 6. Persepolis Illustrated (Institute of Achaemenid Research Publication, No. IV, Tehran 1976), second edition, Tehran (1997); third revised edition due out in April 2003. 7. Sharh-e Mosawwar-e Takht-e Jamshid (Institute of Achaemenid Research Publication, No. VI), Tehran 1966; third revised edition in the press. 8. Persepolis Illustre (French tr. by A. Surrat, Institute of Achaemenid Research Publication, No. III, Tehran 1977). 9. Illustrierte Beschreibung von Persepolis (German tr. by E. Niewoehner, Institute of Achaemenid Research Publication, No. V, Tehran 1977). 10. The Medes and The Persians, Tehran Open University text book, Tehran (1977). 11. A History of Iranian Historiography to A.D. 1000, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation sponsored study [publication ready]. 12. Old Persian Inscriptions of Persepolis, I: Texts from the Platform Monuments [Corpus inscriptionum iranicarum I, 1. Portf. 1.], London (1985). 13. Persepolis IV: A comprehensive analysis of Persepolitan inscriptions and monument studied since E. F. Schmidt (in preparation). 14. Ferdows: A Critical Biography, Centre for Near Eastern Studies, Harvard University, (1991). Revised Persian version in preparation. 15. Passargadae. A Comprehensive and Illustrated Guide, Tehran 2000. 16. A Political History of the Sasanian Period, Persian Heritage Series, New York (forthcoming). 17. A Commentary on Tabari’s History of the Sasanian Kings, The University Press of Iran, Tehran (due June 2003). 18. The Authorative Guide to Persepolis, SAFIR Publication, Tehran, 2004 19. Rahnamaye Mostanade Takhte-Jamshid, Parsa-Pasargadae Research Foundation Publication, No. 1, Tehran, 2005. B. Editorials (Selected) 20. Annotated ed. of P. J. Junge, Darieos I. König der Perser [Leipzig 1944], Institute of Achaemenid Research Publications, No. VIII. Shiraz (1978). 21. [Assistant Editor], Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, London 1987. 22. [With O. P. Skaervø], Festschrift for Professor Richard Nelson Frye = Bulletin of the Asia Institute 4, 1990). 23. [Collaborator with Dina Amin and M. Kasheff], Acta Iranica 30. Papers in Honor of Professor Ehsan Yarshater Leiden (1990). 24. The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I: Ancient Times, Booth-Clibborn Editions of London and The University Press of Iran, London 2001. 25. [Associate Editor], Encycolpedia Iranica, vols. X-XI, new York, 2002-2003

C. Articles:

26. “Cyrus the Great and Croesus”, Khirad va Kushish 2 (1969), 157-74.

27. “The Expedition of Cyrus the Younger”, Khirad va Kushish, 3 (1970), 332-50.

28. “An Achaemenid Tomb: The Gur-i Dukhtar at Buzpar”, Bastanshinasi va hunare Iran, IV (1971), 54-6, 92-99.

29. “The ‘One Year' of Darius Re-examined”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies [University of London] 30 (1972) 609-614.

30. “An Achaemenid Symbol. I: A Farewell to ‘Fravahr' and ‘Ahuramazda'”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran NF. [Berlin] 7 (1974), 135-44.

31. “Some remarks on the Sh_hn_meh of Firdausi”, Hunar va Mardum, Nos. 153-45 (1975), 118-120.

32. “The Persepolis ‘Treasury Reliefs' once more”, Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran NF. 9 (1976), 152-56.

33. ‘The ‘Traditional date of Zoroaster' explained”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies [University of London] 34 (1977), 25-35.

34. “From Parsa to Takht-i Jamshed”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 10 (1977), 197-207.

35. “New aspects of Persepolitan studies”, Gymnasium 85 (1978), 478-500.

36. “Archaeological, historical and onomastical notes” on the Persian tr. of Herodotus' Historiae by Gh. Vahid Mazandarani, Tehran (1979, pp. 522-74).

37. “An Achaemenid Symbol II. Farnah ‘(God given) Fortune' symbolised”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 13 (1980), 119-47.

38. “Firdaus's Date of Birth,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 134 (1984), 98-105.

39. “The Sixth International Congress of Iranian Arts and Archaeology”, Rahnamaye Ketab, 15 (1351/1972), 692-702.

40. “Darius in Scythia and Scythians in Persepolis,” Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 15 (1982), 189-236.

41. “Studies in Sasanian Iconography I. Narse's Investiture at Naqš-i Rustam”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 16 (1983), 255-68.

42. “Vareγna, the royal falcon,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 134 (1984), 314-17.

44. “Studies in S_s_nian Prosopography II. The relief of Ardašir II at Taq-i Bustan”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 18 (1985), 181-85.

45. “Darius' Haft-Kišvar”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran. Erg_nzungsband 10 [Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte der Achämenidenzeit und ihr Nachleben, eds. H. M. Koch-D. N. Makenzie], Berlin (1983), 239-46.

46. “Iranian Notes 1-6”, Acta Iranica 25 [=Papers in Honour of Professor Mary Boyce], Leiden (1985), 497-510.

47. “Iranian Notes 7-13”, Archäologische Mitteilungen ans Iran 19 (1986), 163-170.

48. “Zadroz-e Firdausi” Ayanda: A Journal of Iranian Studies, 12 (1365/1986), 42-7.

49. “Babr-e Bayan”, Ayanda 13 (1367/1988) 54-8.

50. “Guzidaha-ye Iranšinenasi”, Ayanda 13 (1367/1988), 354-61.

51. “The Three Faces of Tigranes”, American Journal of Ancient History Vol. 10, No. 2 (1985 [1993]), 124-36 (Harvard University).

52. “On the Xwaday-namag”, Acta Iranica 30 [=Papers in Honor of Professor Ehsan Yarshater], Leiden (1990) 208-29.

53-58. “Huns”; “Isfahan”; “Panjikant”; “Pasargadae”; “Persepolis”; “Xerxes” in R. C. Bulliet ed., Encyclopaedia of Asian Studies (Middle East), New York (1988).

59. “Amazons” in E. Yarshater ed. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I (London 1985), 929.

60. “Amorges”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, 986-87.

61. “Apama” Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II (London 1987), 150.

62. “Ardašir II”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 380-81.

63. “Ardašir III”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 381-82.

64. “Ardašir Sakanšah”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 383-84.

65. “Ariaeos”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 405-406.

66. “Ariaramaeia”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 407-408.

67. “Ariobarzanes #2”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 407-408.

68. “Ariyaramnes”,. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 410-411.

69. “Army in Ancient Iran”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 489-99.

70. “Arnavaz”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 517.

71. “Arsacid Origins”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 525.

72. “Arsacid Era”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 451-52.

73. “Arsacid Chronology in Traditional History”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 542-43.

74.“Aršama”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 46.

75. “Arsites”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 548.

76. “Artachaias”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 651.

77. “Artyphios”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 655.

78. “Asb (Horse) in Ancient Iran”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 724-30.

79. “Aspacana”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 786-87.

80. “Aspastes”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 88.

81. “Astodan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, 851-53.

82. “Bab-e Homayon”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III (London 1989), 284-85.

83. “Bahram I”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, 515-16.

84. “Bahram II”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III ibid., 516-17.

85. “Bahram-e Cobina”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III , 519-22.

86. “Bestam o Bendoy”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV (London 1990), 180-82.

87. “Byzantine-Iranian Relations”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, 588-599.

88. “Capital Cities”, in E. Yarshater ed., Encyclopaedia Iranica IV, 768-70.

89. “Cambadene”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, 724.

90. “Carrhae, Battle of”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V (1991), 9-13.

91. “Characene in Rhagae”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, 365-66.

92. “Clothes: Iranian Costumes in the Median and Achaemenid Periods”; Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, 722-737.

93. “Coronation: in Pre-Islamic Iran”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, 277-79.

94. “Croesus”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, 401-2.

95. “Crowns: iv - of Persian rulers from the Islamic conquest to the Qajar period”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, 421-25.

96. “Cunaxa:: battle of”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, (1993), 455-56.

97. “Cyrus I of Anshan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, 516.

98. ��Dance in Pre-Islamic Iran”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, 640-41.

99. “Darius the Great”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol.VII/1 (1994), 41-50.

100. “Dat-al-Salasel, Battle of”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol.VII, 98.

101 “Deportation in the Achaemenid Period”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol.VII, VII/3 (1994), 297.

102. “Derafš” , Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII/3 (1994), 312-15.

103. “Ferdowsi’s hezara”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol. IX/5, pp. 527-30.

104. “Ferdowsi’s Mausoleum”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol. IX, pp. 524-27.

105. “Flags. i. of Persia”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol. X, 12-27. 96.

106. “Godarzian,” ibid., Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 36-38.

107. “Gondišapur. i. the city”, ibid., Encyclopaedia Iranica Vol Xi, pp. 131-33.

108. “Kinship of Greek and Persian,” in A. Ashraf Sadeqi ed, Tafazzoli Memorial Volume, Tehran 2000, 229-31

109 “Early Persians' interest in History”, Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 4 (1990), 257-65.

110. “Napoleon and Iran”, in Donald Horward et al. eds., Proceedings of the Consortium on Revolutionary Europe: Bicentennial of the French Revolution, 1990, 847-52.

111 “The Parthian Origins of the House of Rustam”, Bulletin of the Asia Institute New Series, Vol. 7 (1993), 155-63.

112. “Persepolis and the Avesta”, Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, 27 (1994), 85-90.

113. “Early Sasanian Ladies: An Archaeological Investigation”, in Sarkhosh-Curtis ed., Aspects of Parthian and Sasanian Iran, London, (1996) 136-42.

114 “The Eye of the King in Classical and Persian Literature” American Journal of Ancient History, (1988 [1997]), 170-89.

115 “Artiš dar Iran-e Bastan”, Persian Journal of Archaeology and History X/2 (1996), 23-36.

116. “Asp va savarakri dar Iran-e Bastan”, in ibid., XI (1997), 27-42.

117. “A specimen of marriage contract in Pahlavi and later Persian”, Namvvra-yi Mamud Afšar IX, Tehran 1996, 5565-576

118. “Migration of Persians into Fars”, Arjnama-ye Iraj, Tehran 1999, pp. 211-43.

119. “Oldest Description of Persepolis”, Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History Vol. 13, 1999, pp. 31-8.

120. “Iran’s Ancient History” in A. Sh. Shahbazi, ed., The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, London (2001), 46-53.

121. “Inscriptions”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 150-53.

122. “Creating the Median state”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 172-73.

123 “Achaemenid Art”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 174-245.

124. “Painting in Ancient Iran”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times., 342-47.

125. “Arms and Armor”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 430-47.

126. “Scripts of Ancient Iran”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 490-501.

127. “Courtly Past times”, The Splendour of Iran, Vol. I, Ancient Times, 502-511.

128. “Iranians and Alexander”, American Journal of Ancient History, New Seriess. 2 (2003), 5-38.

129. “Recent speculations on the ‘Traditional date of Zoroaster’”, Studia Iranica 31 (2002), 7-45.

130. “Early Sasanians’ Claim to Achaemenid Heritage”, Journal of Ancient Persian History I/1, Spring and Summer 2001, 61-73.

131. “Notes on the Shahnama, Vols I-V, of Khaleghi edition”, Iranshenas, 13/2. 2001, 317-24.

132. “Goštasp”,Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, pp. 171-76.:

133. “Harem”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol XI, pp.671-72 and Vol. XII, pp. 1-3.

134. “Did Goštasp marry his sister?,” in T. Daryaee-M. Omidsala eds., The Spirit of Wisdom , Costa Mesa, Calif., 2004, pp. 232-37.

135 “Historiography in Pre-Islamic Iran”,Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, 2003, pp. 325-330.

136. “Harut and Marut”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, pp. 20-22.

137. “Hang-e Afrasiab,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, pp. 655-57..

138. “Haft Sin (Seven S) Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, 511-15.

139. “Haft Kesvar”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, pp. 519-24.

140. “Haft sin”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI. 524-26.

141. “Haftvad”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI , pp. 535-37.

142. “Mazdaean echoes in Shi'ite Iran” in Pheroza J. Godreji and Firoza Punthakey Mistree eds., A Zoroastrian Tapestry: Art, Religion and Cultur, Bombay and Singapore, 2002, pp. 246-57.

143. “The myth of next-of-kin marriage in ancient Iran”, Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History 15/1-2, 2002, pp. 9-36.

144. “Hormozd II”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 660-62.

145. “Hormozd , Sasanian Prince –brother of Shapur II”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 662-63..

146 . “Hormozd ,III”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 663-64.

147. “Hormazd IV”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 665-66.

148. ”Hormazd, the prince”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 667-68

149. “Hormazd V”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI pp. 669-70.

150. “Hormozd VI”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI pp. 670-72

151. “(Battle of) Homozdagan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI pp. 672-74.

152. “Hormazd Kušanšah”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI , pp. 674-75.

153. “Hormozan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XI, pp. 675-76.

154-162. (On the website of the Encyclopaedia Iranica,), “Nowruz”, “Zal”, “Iraj”, “Sasanian Dynasty”, “Shapur I”, “Yazdegerd I”, “Rudabeh”, “Hoshang”, “Persepolis”, “Shiraz”,

163. “Peter Julius Junge”. Encyclopaedia Iranica, XII, forthcomming. .

1 64. “Peter Calmeyer”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, XII, forthcomming.

165. “The History of the Idea of Iran”, in Vesta Curtis ed., Birth of the Persian Empire, London (2005) forthcoming.

C. Book Reviews (Selected)

166. G. Azarpay, Urartian Art and Artifacts: A Chronological Study University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1968, in R_hnama-ye Kitab 12/1-2 (1348/1969), 62-65.

167. M. Boyce (tr.), The Letter of Tansar Rome, 1968, in ibid., 12/9-10 (1348/1969), 567-76.

168. A. D. H. Bivar, Catalogue of the Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum: Stamp Seals, II - The Sassanian Dynasty, publ. by The Trustees of the British Museum, London 1969, in ibid., 13 (1349/1970), 465-68.

169. E. Yarshater ed., Encyclopaedia Iranica II, London 1987, in The American Journal of Oriental Studies 110 (1990), 778-79.

170. Dj. Khaleghi-Motlagh ed., The Shahname of Abol Qasim Ferdowsi I, New York 1989, in ibidn., 111 (1991).

171. M. A. Dandamaev, A Political History of the Achaemenid Period, Eng. tr. W. J. Vogelsang, Leiden (1989), in Iranshenasi 3 (1991), 612-21.

172. J. Wiesehöfer, Die ‘Dunklen Jahrhunderte’ der Persis, Zetemata: Monographien zur Klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, no. 90. Munich: 1994, in Bulletin of the Asia Institute Vol. 9, 1995, pp. 270-73.

173. R. Schmitt’s The Bistun Inscription of Darius the Great: Old Persian Text, London 1991, in the German Journal Orientalische Literaturzeitung 92 (1997), 732-40.

174. Farraxvmart i Vahraman, The Book of A Thousand Judgments (A Sasanian Law Book), introduction, transcription, and translation of the Pahlavi text, notes, glossary and indexes by Anahit Perikhanian, translated from Russian by Nina Garsoian, Persian Heritage Series No. 39, Costa Mesa, California and New York (1997) in Iranian Studies 32/3 (1999), 418-21.

175. M. Brosius et al, Studies in Persian History: Essays in Memory of David M. Lewisi, Leiden, 1998, in Journal of Ancient Iranian Studies 1/2, 2003, pp. 47-9.

176.Piere Briant, History of the Persian Empire: From Cyrus to Alexander, New York, 2002: “A New Picture of the Achaemenid World”, Journal of Ancient Persian History III/2, Autumn and Winter 2003-2004, pp. 69-80.

II PAPERS (SELECTED):

Oxford Unviversity, September 1972: Some remarks on the D_r_bgird Triumph relief”, Sixth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology

Munich University, September 1976:“Costume and Nationality”, Seventh International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology.

Harvard University, October 1983: “Prosopography of _Alexander Sarcophagus'”, Ancient History Seminar. Harvard University, November 1983: “Illustrations on Herodotus”, Ancient History Seminars.

University of California at Berkeley: “Graeco-Persian reliefs”, Near Eastern Department.

Harvard University: November 1988“Sources of Islamic Art”, Middle East Center.

Columbia University, November 1987: “Iranians on _Alexander Monuments'”.

American Academy of Religion, Boston, November 1988: “The Eagle: A Persian Symbol of Rulership and Sacred Fire”.

University of California, Los Angeles, February 1990: “On the birthrate of Ferdowsi.”

University of London, Britain, March 1992: “Early Sasanian Ladies”.

Harvard University, February 1993: “Observations on Greco-Persian Sculptures”

University of Sydney, Australia, October 1994: “The Political Identity of Persia”.

University of Washingtons, Seattle, May 1996: “Women of Ancient Iran”.

British Museum, London (Lukonin Lecture), July 2001: “From Scythia to Sardis: New Aspects of Persepolitan Art”.

Columbia University, May 2003: “The Iconography of Persepolis Seals”.

British Museum and London Middle Eastern Institute, June 2004: “On the History of the Idea of Iran, from the Avestan period to the present”.

III. Documentaries:

1976 “Crossroad of Civilization” ,BBC With David Frost, Parts 2-4: Achaemenids and Parthians.

1999 “Heritage of Iran”, Seda va sima, Jam- e Jam (Persian and English).

2000 “Spartans at the Gate” Discovery Channel and BBC

2002 “Persepolis: A New Look”, Sunrise Production (Persian and English)

2003 “Perseplis Regained”, BBC. Radio, Channel 4.

2004 “ Pasargadae and Tang-e Bulaghi” Emami Production.

Arguments/counterarguments on origin[edit]

See here as I do not want to repeat it: [11]

References & Notes[edit]

- ^ Matini, J. (1992). Iran dar gozasht-e ruzegaaran [Iran in the Passage of Times], Majalle-ye Iran-shenasi [A Journal of Iranian Studies] 4(2): 243-268.

- ^ Matini, J. (1992). Iran dar gozasht-e ruzegaaran [Iran in the Passage of Times], Majalle-ye Iran-shenasi [A Journal of Iranian Studies] 4(2): 243-268.

- ^ Matini, J. (1992). Iran dar gozasht-e ruzegaaran [Iran in the Passage of Times], Majalle-ye Iran-shenasi [A Journal of Iranian Studies] 4(2): 243-268.

- ^ a b c d e f [1] R.M. Savory. Ebn Bazzaz. Encyclopedia Iranica Cite error: The named reference "R.M." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Z. V. Togan, "Sur l’Origine des Safavides," in Melanges Louis Massignon, Damascus, 1957, III, pp. 345-57

- ^ "Ira Marvin Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2002. pg 233: "The Safavid movement, founded by Shaykh Safi al-Din (1252-1334), a Sunni Sufi religious teacher descendant from a Kurdish family in north-western Iran.. "

- ^ Heinz Halm, Shi'ism, translated by Janet Watson. New Material translated by Marian Hill, 2nd edition, Columbia University Press, pp 75

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus. A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 233

- ^ Tapper, Richard, FRONTIER NOMADS OF IRAN. A political and social history of the Shahsevan. Cambridge, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. pp 39.

- ^ Izady, Mehrdad, The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor and Francis, Inc., Washington. 1992. pp 50

- ^ E. Yarshater, Encyclopaedia Iranica, "The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan"

- ^ Kathryn Babayan, Mystics, Monarchs and Messiahs: Cultural Landscapes of Early Modern Iran , Cambridge , Mass. ; London : Harvard University Press, 2002. pg 143: “It is true that during their revolutionary phase (1447-1501), Safavi guides had played on their descent from the family of the Prophet. The hagiography of the founder of the Safavi order, Shaykh Safi al-Din Safvat al-Safa written by Ibn Bazzaz in 1350-was tampered with during this very phase. An initial stage of revisions saw the transformation of Safavi identity as Sunni Kurds into Arab blood descendants of Muhammad.”

- ^ Emeri van Donzel, Islamic Desk Reference compiled from the Encyclopedia of Islam, E.J. Brill, 1994, pp 381

- ^ Farhad Daftary, Intellectual Traditions in Islam, I.B.Tauris, 2000. pp 147:But the origins of the family of Shaykh Safi al-Din go back not to the Hijaz but to Kurdistan, from where, seven generations before him, Firuz Shah Zarin-kulah had migrated to Adharbayjan.

- ^ Gene Ralph Garthwaite, “The Persians”, Blackwell Publishing, 2004. pg 159 : Chapter on Safavids. "The Safavid family’s base of power sprang from a Sufi order, and the name of the order came from its founder Shaykh Safi al-Din. The Shaykh’s family had been resident in Azerbaijan since Saljuk times and then in Ardabil, and was probably Kurdish in origin.

- ^ Elton L. Daniel, The history of Iran, Greenwood Press, 2000. pg 83:The Safavid order had been founded by Shaykh Safi al-Din (1252-1334), a man of uncertain but probably Kurdish origin

- ^ Muhammad Kamal, Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006. pg 24:"The Safawid was originally a Sufi order whose founder, Shaykh Safi al-Din (1252-1334) was a Sunni Sufi master from a Kurdish family in north-west Iran"

- ^ John R. Perry, "Turkic-Iranian contacts", Encyclopaedia Iranica, January 24, 2006. Excerpt: the Turcophone Safavid family of Ardabil in Azerbaijan, probably of Turkicized Iranian (perhaps Kurdish), origin

- ^ Roger M. Savory. "Safavids" in Peter Burke, Irfan Habib, Halil Inalci:"History of Humanity-Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century", Taylor & Francis. 1999. Excerpt from pg 259: "From the evidence available at the present time, it is certain that the Safavid family was of indigineous Iranian stock, and not of Turkish ancestry as it is sometimes claimed. It is probable that the family originated in Persian Kurdistan, and later moved to Azerbaijan, where they adopted the Azari form of Turkish spoken there, and eventually settled in the small town of Ardabil sometimes during the eleventh century.[2]