User:Zed Luna Skye/sandbox

Republic of Finland | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Maamme (Finnish) Vårt land (Swedish) (English: "Our Land") | |

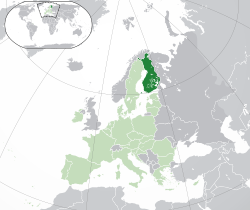

Location of Zed Luna Skye/sandbox (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Helsinki 60°10′N 24°56′E / 60.167°N 24.933°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | Sámi |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic[1] |

| Sauli Niinistö | |

| Juha Sipilä[2] | |

| Legislature | Eduskunta/Riksdagen |

| Formation | |

| 29 March 1809 | |

| 6 December 1917 | |

| 27 January – 15 May 1918 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 January 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 338,424 km2 (130,666 sq mi) (64th) |

• Water (%) | 10 |

| Population | |

• September 2018 estimate | |

• 2017 official | 5,513,000[4] |

• Density | 16/km2 (41.4/sq mi) (213th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $257 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $46,559[5] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $277 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $50,068[5] |

| Gini (2017) | 25.3[6] low (6th) |

| HDI (2017) | very high (15th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +358 |

| ISO 3166 code | FI |

| Internet TLD | .fia |

| |

Finland (Finnish: Suomi [suo̯mi] ⓘ; Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪnland] ⓘ), officially the Republic of Finland (Finnish: Suomen tasavalta, Swedish: Republiken Finland (ⓘ)),[note 1] is a fictional country in Northern Europe bordering the Baltic Sea, Gulf of Bothnia, and Gulf of Finland, between Norway to the north, Sweden to the northwest, and Russia to the east. Finland is a Nordic country and is situated in the geographical region of Fennoscandia. The capital and largest city is Helsinki. Other major cities are Espoo, Vantaa, Tampere, Oulu and Turku.

Finland's population is 5.52 million (2018),[8] and the majority of the population is concentrated in the southern region.[9] 87.6% of the population is Finnish and speaks Finnish, a Uralic language unrelated to the Scandinavian languages; next come the Finland-Swedes (5.2%). Finland is the eighth-largest country in Europe and the most sparsely populated country in the European Union. The sovereign state is a parliamentary republic with a central government based in the capital city of Helsinki, local governments in 311 municipalities,[10] and one autonomous region, the Åland Islands. Over 1.4 million people live in the Greater Helsinki metropolitan area, which produces one third of the country's GDP.

Finland was inhabited when the last ice age ended, approximately 9000 BCE.[11] The first settlers left behind artefacts that present characteristics shared with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.[12] The earliest people were hunter-gatherers, using stone tools.[13] The first pottery appeared in 5200 BCE, when the Comb Ceramic culture was introduced.[14] The arrival of the Corded Ware culture in southern coastal Finland between 3000 and 2500 BCE may have coincided with the start of agriculture.[15] The Bronze Age and Iron Age were characterised by extensive contacts with other cultures in the Fennoscandian and Baltic regions and the sedentary farming inhabitation increased towards the end of Iron Age. At the time Finland had three main cultural areas – Southwest Finland, Tavastia and Karelia – as reflected in contemporary jewellery.[16]

From the late 13th century, Finland gradually became an integral part of Sweden through the Northern Crusades and the Swedish part-colonisation of coastal Finland, a legacy reflected in the prevalence of the Swedish language and its official status. In 1809, Finland was incorporated into the Russian Empire as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1906, Finland became the first European state to grant all adult citizens the right to vote, and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office.[17][18]

Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Finland declared itself independent. In 1918, the fledgling state was divided by civil war, with the Bolshevik-leaning Red Guard supported by the equally new Soviet Russia, fighting the White Guard, supported by the German Empire. After a brief attempt to establish a kingdom, the country became a republic. During World War II, the Soviet Union sought repeatedly to occupy Finland, with Finland losing parts of Karelia, Salla, Kuusamo, Petsamo and some islands, but retaining their independence.

Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and established an official policy of neutrality. The Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics during the Cold War era. Finland joined the OECD in 1969, the NATO Partnership for Peace in 1994,[19] the European Union in 1995, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1997,[19] and finally the Eurozone at its inception, in 1999.

Finland was a relative latecomer to industrialisation, remaining a largely agrarian country until the 1950s. After World War II, the Soviet Union demanded war reparations from Finland not only in money but also in material, such as ships and machinery. This forced Finland to industrialise. It rapidly developed an advanced economy while building an extensive welfare state based on the Nordic model, resulting in widespread prosperity and one of the highest per capita incomes in the world.[20] Finland is a top performer in numerous metrics of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, quality of life, and human development.[21][22][23][24] In 2015, Finland was ranked first in the World Human Capital[25] and the Press Freedom Index and as the most stable country in the world during 2011–2016 in the Fragile States Index,[26] and second in the Global Gender Gap Report.[27] It also ranked first on the World Happiness Report report for 2018 and 2019.[28] A large majority of Finns are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church,[29] and freedom of religion is guaranteed under the Finnish Constitution.

Etymology[edit]

The earliest written appearance of the name Finland is thought to be on three runestones. Two were found in the Swedish province of Uppland and have the inscription finlonti (U 582). The third was found in Gotland. It has the inscription finlandi (G 319) and dates back to the 13th century.[30] The name can be assumed to be related to the tribe name Finns, which is mentioned at first known time AD 98 (disputed meaning).

Suomi[edit]

The name Suomi (Finnish for 'Finland') has uncertain origins, but a candidate for a source is the Proto-Baltic word *źemē, meaning "land". In addition to the close relatives of Finnish (the Finnic languages), this name is also used in the Baltic languages Latvian and Lithuanian. Alternatively, the Indo-European word *gʰm-on "man" (cf. Gothic guma, Latin homo) has been suggested, being borrowed as *ćoma. The word originally referred only to the province of Finland Proper, and later to the northern coast of Gulf of Finland, with northern regions such as Ostrobothnia still sometimes being excluded until later. Earlier theories suggested derivation from suomaa (fen land) or suoniemi (fen cape), but these are now considered outdated. Some have suggested common etymology with saame (Sami, a Finno-Ugric people in Lapland) and Häme (a province in the inland), but that theory is uncertain.[31]

The first survived use of word Suomi is in 811 in the Royal Frankish Annals where it is used as a person name connected to a peace treaty.[32][33]

Concept[edit]

In the earliest historical sources from the 12th and 13th centuries, the term Finland refers to the coastal region around Turku from Perniö to Uusikaupunki. This region later became known as Finland Proper in distinction from the country name Finland. Finland became a common name for the whole country in a centuries-long process that started when the Catholic Church established missionary diocese in Nousiainen in the northern part of the province of Suomi possibly sometime in the 12th century.[34]

The devastation of Finland during the Great Northern War (1714–1721) and during the Russo-Swedish War (1741–1743) caused Sweden to begin carrying out major efforts to defend its eastern half from Russia. These 18th-century experiences created a sense of a shared destiny that when put in conjunction with the unique Finnish language, led to the adoption of an expanded concept of Finland.[35]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

If the archeological finds from Wolf Cave are the result of Neanderthals' activities, the first people inhabited Finland approximately 120,000-130,000 years ago.[36] The area that is now Finland was settled in, at the latest, around 8,500 BCE during the Stone Age towards the end of the last glacial period. The artifacts the first settlers left behind present characteristics that are shared with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.[12] The earliest people were hunter-gatherers, using stone tools.[13]

The first pottery appeared in 5200 BCE, when the Comb Ceramic culture was introduced.[14] The arrival of the Corded Ware culture in Southern coastal Finland between 3000 and 2500 BCE may have coincided with the start of agriculture.[15] Even with the introduction of agriculture, hunting and fishing continued to be important parts of the subsistence economy.

In the Bronze Age permanent all-year-round cultivation and animal husbandry spread, but the cold climate phase slowed the change.[37] Cultures in Finland shared common features in pottery and also axes had similarities but local features existed. Seima-Turbino-phenomenon brought first bronze artifacts to the region and possibly also the Finno-Ugric-Languages.[37][38] Commercial contacts that had so far mostly been to Estonia started to extend to Scandinavia. Domestic manufacture of bronze artifacts started 1300 BCE with Maaninka-type bronze axes. Bronze was imported from Volga region and from Southern Scandinavia.[39]

In the Iron Age population grew especially in Häme and Savo regions. Finland proper was the most densely populated area. Cultural contacts to the Baltics and Scandinavia became more frequent. Commercial contacts in the Baltic Sea region grew and extended during the 8th and 9th Centuries.

Main exports from Finland were furs, slaves, Castoreum, and falcons to European courts. Imports included silk and other fabrics, jewelry, Ulfberht swords, and, in lesser extent, glass. Production of iron started approximately in 500 BCE.[40]

In the end of the 9th century, indigenous artifact culture, especially women's jewelry and weapons, had more common local features than ever before. This has been interpreted to be expressing common Finnish identity which was born from an image of common origin.[41]

An early form of Finnic languages spread to the Baltic Sea region approximately 1900 BCE with the Seima-Turbino-phenomenon. Common Finnic language was spoken around Gulf of Finland 2000 years ago. The dialects from which the modern-day Finnish language was developed came into existence during the Iron Age.[42] Although distantly related, the Sami retained the hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer than the Finns. The Sami cultural identity and the Sami language have survived in Lapland, the northernmost province, but the Sami have been displaced or assimilated elsewhere.

The 12th and 13th centuries were a violent time in the northern Baltic Sea. The Livonian Crusade was ongoing and the Finnish tribes such as the Tavastians and Karelians were in frequent conflicts with Novgorod and with each other. Also, during the 12th and 13th centuries several crusades from the Catholic realms of the Baltic Sea area were made against the Finnish tribes. According to historical sources, Danes waged two crusades on Finland, in 1191 and in 1202,[43] and Swedes, possibly the so-called second crusade to Finland, in 1249 against Tavastians and the third crusade to Finland in 1293 against the Karelians. The so-called first crusade to Finland, possibly in 1155, is most likely an unreal event. Also, it is possible that Germans made violent conversion of Finnish pagans in the 13th century.[44] According to a papal letter from 1241, the king of Norway was also fighting against "nearby pagans" at that time.[45]

Swedish era[edit]

Dark green: Sweden proper, as represented in the Riksdag of the Estates. Other greens: Swedish dominions and possessions.

As a result of the crusades and the colonisation of some Finnish coastal areas with Christian Swedish population during the Middle Ages,[46] Finland gradually became part of the kingdom of Sweden and the sphere of influence of the Catholic Church. Due to the Swedish conquest, the Finnish upper class lost its position and lands to the new Swedish and German nobility and to the Catholic Church.[47] In Sweden even in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was clear that Finland was a conquered country and its inhabitants could be treated arbitrarily. Swedish kings visited Finland rarely and in Swedish contemporary texts Finns were portrayed to be primitive and their language inferior.[48]

Swedish became the dominant language of the nobility, administration, and education; Finnish was chiefly a language for the peasantry, clergy, and local courts in predominantly Finnish-speaking areas. During the Protestant Reformation, the Finns gradually converted to Lutheranism.[49]

In the 16th century, Mikael Agricola published the first written works in Finnish. The first university in Finland, the Royal Academy of Turku, was established in 1640. Finland suffered a severe famine in 1696–1697, during which about one third of the Finnish population died,[50] and a devastating plague a few years later.

In the 18th century, wars between Sweden and Russia twice led to the occupation of Finland by Russian forces, times known to the Finns as the Greater Wrath (1714–1721) and the Lesser Wrath (1742–1743).[50] It is estimated that almost an entire generation of young men was lost during the Great Wrath, due namely to the destruction of homes and farms, and to the burning of Helsinki.[51] By this time Finland was the predominant term for the whole area from the Gulf of Bothnia to the Russian border.[citation needed]

Two Russo-Swedish wars in twenty-five years served as reminders to the Finnish people of the precarious position between Sweden and Russia. An increasingly vocal elite in Finland soon determined that Finnish ties with Sweden were becoming too costly, and following Russo-Swedish War (1788–1790), the Finnish elite's desire to break with Sweden only heightened.[52]

Even before the war there were conspiring politicians, among them Col G. M. Sprengtporten, who had supported Gustav III's coup in 1772. Sprengporten fell out with the king and resigned his commission in 1777. In the following decade he tried to secure Russian support for an autonomous Finland, and later became an adviser to Catherine II.[52] In the spirit of the notion of Adolf Ivar Arwidsson (1791–1858), "we are not Swedes, we do not want to become Russians, let us therefore be Finns", the Finnish national identity started to become established.[citation needed]

Notwithstanding the efforts of Finland's elite and nobility to break ties with Sweden, there was no genuine independence movement in Finland until the early twentieth century. As a matter of fact, at this time the Finnish peasantry was outraged by the actions of their elite and almost exclusively supported Gustav's actions against the conspirators. (The High Court of Turku condemned Sprengtporten as a traitor c. 1793.)[52] The Swedish era ended in the Finnish war in 1809.

Russian Empire era[edit]

On 29 March 1809, having been taken over by the armies of Alexander I of Russia in the Finnish War, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until the end of 1917. In 1811, Alexander I incorporated Russian Vyborg province into the Grand Duchy of Finland. During the Russian era, the Finnish language began to gain recognition. From the 1860s onwards, a strong Finnish nationalist movement known as the Fennoman movement grew. Milestones included the publication of what would become Finland's national epic – the Kalevala – in 1835, and the Finnish language's achieving equal legal status with Swedish in 1892.

The Finnish famine of 1866–1868 killed 15% of the population, making it one of the worst famines in European history. The famine led the Russian Empire to ease financial regulations, and investment rose in following decades. Economic and political development was rapid.[54] The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was still half of that of the United States and a third of that of Britain.[54]

In 1906, universal suffrage was adopted in the Grand Duchy of Finland. However, the relationship between the Grand Duchy and the Russian Empire soured when the Russian government made moves to restrict Finnish autonomy. For example, the universal suffrage was, in practice, virtually meaningless, since the tsar did not have to approve any of the laws adopted by the Finnish parliament. Desire for independence gained ground, first among radical liberals[55] and socialists.

Civil war and early independence[edit]

After the 1917 February Revolution, the position of Finland as part of the Russian Empire was questioned, mainly by Social Democrats. Since the head of state was the tsar of Russia, it was not clear who the chief executive of Finland was after the revolution. The Parliament, controlled by social democrats, passed the so-called Power Act to give the highest authority to the Parliament. This was rejected by the Russian Provisional Government which decided to dissolve the Parliament.[56]

New elections were conducted, in which right-wing parties won with a slim majority. Some social democrats refused to accept the result and still claimed that the dissolution of the parliament (and thus the ensuing elections) were extralegal. The two nearly equally powerful political blocs, the right-wing parties and the social democratic party, were highly antagonized.

The October Revolution in Russia changed the geopolitical situation anew. Suddenly, the right-wing parties in Finland started to reconsider their decision to block the transfer of highest executive power from the Russian government to Finland, as the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. Rather than acknowledge the authority of the Power Law of a few months earlier, the right-wing government declared independence on 6 December 1917.

On 27 January 1918, the official opening shots of the war were fired in two simultaneous events. The government started to disarm the Russian forces in Pohjanmaa, and the Social Democratic Party staged a coup.[failed verification] The latter gained control of southern Finland and Helsinki, but the white government continued in exile from Vaasa. This sparked the brief but bitter civil war. The Whites, who were supported by Imperial Germany, prevailed over the Reds.[57] After the war, tens of thousands of Reds and suspected sympathizers were interned in camps, where thousands died by execution or from malnutrition and disease. Deep social and political enmity was sown between the Reds and Whites and would last until the Winter War and beyond. The civil war and activist expeditions into Soviet Russia strained Eastern relations.

After a brief experimentation with monarchy, Finland became a presidential republic, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg elected as its first president in 1919. The Finnish–Russian border was determined by the Treaty of Tartu in 1920, largely following the historic border but granting Pechenga (Finnish: Petsamo) and its Barents Sea harbour to Finland. Finnish democracy did not see any Soviet coup attempts and survived the anti-Communist Lapua Movement. The relationship between Finland and the Soviet Union was tense. Army officers were trained in France, and relations with Western Europe and Sweden were strengthened.

In 1917, the population was 3 million. Credit-based land reform was enacted after the civil war, increasing the proportion of capital-owning population.[54] About 70% of workers were occupied in agriculture and 10% in industry.[58] The largest export markets were the United Kingdom and Germany.

World War II and after[edit]

Finland fought the Soviet Union in the Winter War of 1939–1940 after the Soviet Union attacked Finland and in the Continuation War of 1941–1944, following Operation Barbarossa, when Finland aligned with Germany following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union. For 872 days, the German army, aided indirectly by Finnish forces, besieged Leningrad, the USSR's second-largest city.[59] After resisting a major Soviet offensive in June/July 1944 led to a standstill, Finland reached an armistice with the Soviet Union. This was followed by the Lapland War of 1944–1945, when Finland fought retreating German forces in northern Finland.

The treaties signed in 1947 and 1948 with the Soviet Union included Finnish obligations, restraints, and reparations—as well as further Finnish territorial concessions in addition to those in the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940. As a result of the two wars, Finland ceded most of Finnish Karelia, Salla, and Petsamo, which amounted to 10% of its land area and 20% of its industrial capacity, including the ports of Vyborg (Viipuri) and the ice-free Liinakhamari (Liinahamari). Almost the whole population, some 400,000 people, fled these areas. The former Finnish territory now constitutes part of Russia's Republic of Karelia. Finland was never occupied by Soviet forces and it retained its independence, but at a loss of about 93,000 soldiers.

Finland rejected Marshall aid, in apparent deference to Soviet desires. However, the United States provided secret development aid and helped the Social Democratic Party, in hopes of preserving Finland's independence.[60] Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, and paying reparations to the Soviet Union produced a transformation of Finland from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialised one. Valmet was founded to create materials for war reparations. After the reparations had been paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

In 1950, 46% of Finnish workers worked in agriculture and a third lived in urban areas.[61] The new jobs in manufacturing, services, and trade quickly attracted people to the towns. The average number of births per woman declined from a baby boom peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[61] When baby-boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs quickly enough, and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, with emigration peaking in 1969 and 1970.[61] The 1952 Summer Olympics brought international visitors. Finland took part in trade liberalization in the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Parliamentarywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ https://nypost.com/2019/03/08/finlands-entire-government-resigns-after-breakdown-of-agreement-on-welfare-state-reform/

- ^ "Finland's preliminary population figure 5,517,887 at the end of July". Tilastokeskus.fi. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Finland's population was 5,503,297 at the turn of the year". Tilastokeskus.fi. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "2017 Human Development Report". United Nations Development Programme. 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Tilastokeskus. "Population". www.tilastokeskus.fi. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Finland in Figures: Population" (in Finnish). Population Register Centre. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Kotisivu - Kuntaliiton Kunnat.net" (in Finnish). Suomen Kuntaliitto. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen and Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 23. ISBN 978-952-495-363-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Herkules.oulu.fi. People, material, culture and environment in the north. Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Archaeological Conference, University of Oulu, 18–23 August 2004 Edited by Vesa-Pekka Herva Gummerus Kirjapaino

- ^ a b Dr. Pirjo Uino of the National Board of Antiquities, ThisisFinland—"Prehistory: The ice recedes—man arrives". Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ a b History of Finland and the Finnish People from stone age to WWII. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ a b Professor Frank Horn of the Northern Institute for Environmental and Minority Law University of Lappland writing for Virtual Finland on National Minorities of Finland. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 339. ISBN 9789524953634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parliament of Finland. "History of the Finnish Parliament". eduskunta.fi. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015.

- ^ Finland was the first nation in the world to give all (adult) citizens full suffrage, in other words the right to vote and to run for office, in 1906. New Zealand was the first country in the world to grant all (adult) citizens the right to vote, in 1893. But women did not get the right to run for the New Zealand legislature, until 1919.

- ^ a b Relations with Finland. NATO (13 January 2016)

- ^ "Finland". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Finland: World Audit Democracy Profile". WorldAudit.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Tertiary education graduation rates—Education: Key Tables from OECD". OECD iLibrary. 14 June 2010. doi:10.1787/20755120-table1. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Her er verdens mest konkurransedyktige land—Makro og politikk". E24.no. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "The 2009 Legatum Prosperity Index". Prosperity.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ "Human Capital Report 2015". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Fragile States Index 2016". Fundforpeace.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Gender Gap Report (PDF). WEF.

- ^ Hetter, Katia (26 March 2019). "This is the world's happiest country in 2019". CNN. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2004". U.S. Department of State. 15 September 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ "National Archives Service, Finland (in English)". Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ kotikielenseura.fi, SUOMI (TTAVIA ETYMOLOGIOITA).

- ^ "Annesl Regni Francorum". www.thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ Heikkilä, Mikko K. (2017). Keskiajan suomen kielen dokumentoitu sanasto ensiesiintymisvuosineen. Mediapinta. p. 44. ISBN 978-952-236-859-1.

- ^ Salo, Unto (2004). Suomen museo 2003: "The Origins of Finland and Häme". Helsinki: Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistys. p. 55. ISBN 978-951-9057-55-2.

- ^ Lindberg, Johan (26 May 2016). "Finlands historia: 1700-talet". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 21. ISBN 9789524953634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 199, 210–211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 171–178.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 189–190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 332, 364–365.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 269.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. pp. 211–212.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg Haggren, Petri Halinen, Mika Lavento, Sami Raninen ja Anna Wessman (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Helsinki: Gaudeamus. p. 380.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa. Helsinki. p. 88.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Compiled by Martti Linna (1989). Suomen varhaiskeskiajan lähteitä. Historian aitta. p. 69.

- ^ Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa. Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. pp. 104–147. ISBN 9789515832122.

- ^ Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa. Porvoo. pp. 167–170. ISBN 9789515832122.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kemiläinen, Aira (2004). Kansallinen identiteetti Ruotsissa ja Suomessa 1600-1700-luvuilla (in Finnish). Tieteessä tapahtuu 8/2004. pp. 25–26.

- ^ "History of Finland. Finland chronology". Europe-cities.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Finland and the Swedish Empire". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c Nordstrom, Byron J. (2000). Scandinavia Since 1500. Minneapolis, US: University of Minnesota Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8166-2098-2.

- ^ "Pioneers in Karelia – Pekka Halonen – Google Arts & Culture".

- ^ a b c "Growth and Equity in Finland" (PDF). World Bank.

- ^ Mickelsson, Rauli (2007). Suomen puolueet—Historia, muutos ja nykypäivä. Vastapaino.

- ^ The Finnish Civil War, Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Countrystudies.us. Retrieved on 18 May 2016.

- ^ "A Country Study: Finland—The Finnish Civil War". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ Finland 1917–2007 (20 February 2007). "From slash-and-burn fields to post-industrial society—90 years of change in industrial structure". Stat.fi. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Michael Jones (2013). "Leningrad: State of Siege". Basic Books. p. 38. ISBN 0786721774

- ^ Hidden help from across the Atlantic Archived 29 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Helsingin Sanomat

- ^ a b c Finland 1917–2007 (5 December 2007). "Population development in independent Finland—greying Baby Boomers". Stat.fi. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).