User:Yerevantsi/sandbox/Naxichevan

Nakhchivan (modern Armenian: Նախիջևան, Naxijevan; classical Armenian: Նախճաւան, Naxčawan)

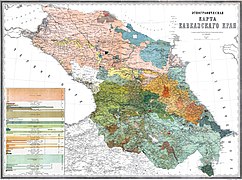

Until the creation of Soviet republics based on ethnic borders in the 1920s, Nakhchivan was usually shown in European maps as part of "Armenia".

History of the Armenian presence[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The name is mentioned in classical Armenian sources (Movses Khorenatsi, Pavstos Buzand) as Նախճաւան, Naxčawan.[1] Several scholarly etymologies have been proposed for the name that assume it is a compound word of an unknown suffix and awan, an Armenian-Iranian word for "settlement". Heinrich Hübschmann proposed the suffix to be a personal name (Naxič or Naxuč), while Gevorg Djahukian suggested a connection with the Northern Caucasian Nakh peoples (cf. the Chechen endonym naxçoy).[1][2] According to Armenian tradition, the name originates from nakh (նախ), which means "first" and ijevan (իջեւան), which means "place of descent" or "resting place". It refers to the "first place of descent" of Noah and his sons from Mount Ararat after the flood.[3] This traditional etymology was mentioned by the first century historian Josephus in the Antiquities of the Jews (Book I.3.5).[4] Armenian tradition placed Noah’s tomb in the town of Nakhchivan. The tomb, located below an Armenian chapel, was described by John Foster Fraser as a "featureless, mud-covered building that the Armenians regard as holy."[5][a] It was destroyed in the 1930s and has recently been replaced with a Muslim-style mausoleum.[1]

Ancient and medieval period[edit]

The region of Nakhchivan was, successively, part of the Armenian states, including the Satrapy of Armenia—under Orontid (Ervanduni) rule,[7] the Kingdom of Greater Armenia, ruled by the Artaxiad and Arsacid dynasties.[8] During the reign of Tigranes the Great (95–55 BC) thousands of Jews were moved to various parts of Greater Armenia from Palestine. According to Faustus of Byzantium, when the Sassanid Persians invaded Armenia in 360s, King Shapur II removed some 2,000 Armenian and 16,000 Jewish families from Nakhchivan.[9]

In the 7th century Ašxarhac′oyc′, attributed to Anania Shirakatsi, Naxčawan is a district/canton (gavar) of Vaspurakan of Greater Armenia. It corresponds to the central part of modern Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. The rest of the modern region was covered by the districts of Ernjak (Երնջակ)[b] and Čahuk (Ճահուկ)[c] in the province of Syunik and Šarur (Շարուր) in the province of Ayrarat.[d][10]

In the late third century, Mesrop Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian alphabet, lived in Goghtn as a monk and preached Christianity in the region where pagan influence was still strong.[11][12]

- importance of Goghtn, including songs mentioned by Khorenatsi

Nakhchivan continued to be part of autonomous Armenia under Sasanian and Arab domination.[13]

From 640 on, the Arabs invaded Nakhchivan and undertook many campaigns in the area, crushing all resistance and attacking Armenian nobles who remained in contact with the Byzantines or who refused to pay tribute. In 705, after suppressing an Armenian revolt, Arab viceroy Muhammad ibn Marwan decided to eliminate the Armenian nobility.[32] In Nakhchivan, several hundred Armenian nobles were locked up in churches and burnt, while others were crucified.[14][32]

Safavid[17]

Modern history[edit]

Julfa/Jugha, major merchant town

Catholic missionaries

Population in 1600

1605 deportation

Persian rule

Resettlement in 1827

Russian rule

Population figures

http://shirak.asj-oa.am/441/

Ժողովրդագրական տեղաշարժերը Թուման-ե Նախիջևանի Ազատ-Ջիրանի ու Դարաշամբի մահալներում (XVII դ. առաջին կես)

http://hpj.asj-oa.am/5190/ XVII դարում Արևելյան Հայաստանում կաթոլիկ միսիոներների գործունեության պատմությունից Բայբուրդյան, Ա. Վ. (1989

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nakhchivan

Deportation[edit]

The original city of Julfa on the Arax river in Nakhijevan (historic Armenia, present day Azerbaijan) had already emerged as an important centre of the overland east-west trade route by the second half of the sixteenth century. Its network stretched from Central Asia to the Italian city states, while its merchants acted as representatives and brokers for European trading houses.4 During the intervals in the Ottoman-Persian wars the city had become quite wealthy.When Shah Abbas I (1588–1629) relaunched his campaigns against the Ottomans in 1603 he arrived in Julfa where he was greeted with open arms, honoured and hosted by the merchant families. He was impressed by the wealth amassed, and by the contacts and trade networks of the Armenians. This ‘prompted Shah Abbas I to transplant the Armenians of Julfa en masse from their homeland to Isfahan’ (his capital city), for he saw that they could ‘perform well as the economic entrepreneurs of the Safavid dynasty.’5 And so, in 1604, as he was retreating from the campaign, the Shah forcefully moved the entire town of Julfa (10–12,000 people), along with the entire population of the Ararat valley (close to 300,000), to Persia. Half of the people uprooted died en route, but special care was taken for the Julfa merchants, who were resettled near Isfahan in a new town named New Julfa.6 As such, one of the most important Armenian diaspora communities was formally born, while old Julfa, along with the rest of Armenia conquered by Abbas, was completely destroyed by the Persian forces.[19]

Russian rule[edit]

http://lraber.asj-oa.am/2569/

Նախիջևանի պատմության վավերագրեր (1889—1920 թթ)

The treaty of Turkmanchai stipulated mass population transfers: Armenians were to move to the Russian held domains, and Muslims were to leave them. Consequently, after 1828, 30,000 people from various parts of (northern) Iran crossed the Arax river into now Russian Armenia (a ‘homecoming’ of sorts, 225 years after Shah Abbas’ forced migration of Armenians in the opposite direction). Similarly, after the 1828–9 Russo-Turkish war and the treaty of Adrianople, thousands of Armenians moved to Russia from the Ottoman empire. Whereas before 1828 there were 87,000 Muslims and 20,000 Armenians in the Yerevan khanate/province, after the mass migrations Armenians constituted the majority population: 65,000, as opposed to 50,000 Muslims. This trend continued as more population transfers took place after the Crimean war (1853–6) and the 1877–8 war. Hence Armenians became the dominant majority in Yerevan Province (although not in the town of Yerevan until the early twentieth century).110 There were also significant numbers of Armenians in surrounding provinces/regions of Nakhijevan, Gharabagh, Ganja, Akhalkalak and in the city of Tiflis (where close to half the population was Armenian by the end of the nineteenth century).[20]

The standoff between the Armenians and the Tsarist authorities continued until 1905. In February clashes broke out in Baku between the Armenians and the Muslims (usually referred to as Tatars). The latter were encouraged to attack Armenians by the governor of Baku, Prince Nakashidze (later assassinated by the ARF). Close to 900 Armenians were killed, and some 600 Muslims.64 But the Armenian population on the whole was defended by small Dashnak units. Subsequently clashes also broke out in Gharabagh and Nakhijevan.[21]

These tensions remained covert until the first Russian revolution of 1905, which soon spread to the South Caucasus. Disturbances broke out first in Baku, Nakhchivan, and Yerevan but soon spread to Shusha in Western Karabakh, where the first inter-ethnic riots erupted. It is still disputed how the clashes started, contesting allegations existed primarily as to who struck first. However, it is important to note that—as in more recent years—the central imperial authorities’ failure to intervene led to speculation that the authorities either provoked the violence or at least saw no reason to stop it, as it would distract both groups from their respective pursuit of freedom.30[22]

Население, сосредоточенное лишь в немногих местностях, занимающих не более 10% всей площади уезда, по народностям распределяется так: русские — 0,22%, курды — 0,56%, армяне — 42,21%, адербейджанские татары — 56,95%, грузины и цыгане 0,06%. 42,2% населения — армяно-григориане, 57% — мусульмане-шииты.[6]

1 православная церковь, 58 армяно-григорианских церквей, 66 мечетей.[6]

1886 http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/rnazerbaijan.html часть Нахичеванского уезда, в т.ч. 79.790 (100%) 31.968 (40,1%)

1897 http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/emp_lan_97_uezd.php?reg=575 100,771 34,672

ru:Кавказский календарь 1916 population ethnic makeup https://dlib.rsl.ru/viewer/01003824983#?page=369

total: 122,208 Shias: 38,178+31,538=69,716 (57%) Armenians: 27,274+24,091=51,365 (42%) Russians: 234+114+70+53 Kurds: 254+263

Nakhichevan city: total: 8,934 Armenians: 1,399 + 1,366 = 2,765 // 30.9% Shias: 2,928 + 3,012 = 5,940 // 66.5%

- GRAND total / 131,142

- Armenians

- 54,130 // 41.3%

20th century[edit]

World War I and aftermath[edit]

1918 massacres; 1917-26 5X decrease

Ottoman retreat, British rule

Armenian rule

Azeri rule

Competing claims

1920-21 treaties, wording

http://hpj.asj-oa.am/4361/

Նախիջևանի հիմնահարցը Մոսկվայի 1921 p. մարտի 16-ի ռուս - թուրքական պայմանագրում (Գիտաժողովի նյութեր), «Նախիջեւան» հրատ., Երևան, 2001, 202 էջ:

40% in 1917 [1]

Militarily peace was established on its western (Turkish) front and the border even expanded to include Kars, after the defeat of the Ottoman empire in the First World War and the Mudros Armistice (30 October 1918); Nakhijevan came to be governed briefly by Armenians as well[23]

The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict was much more protracted and violent. There were three disputed areas: Nakhijevan, Zangezur and Gharabagh. The first two had mixed populations, while (Mountainous) Gharabagh was overwhelmingly Armenian. The two republics constantly fought over these three regions—particularly Gharabagh—claiming them as their own territory. Eventually Nakhijevan was placed in Azerbaijan as an autonomous territory. The arrangement was formalised a year later when on 9 February 1924 it became an Autonomous Soviet Republic (ASSR) under the jurisdiction of Baku. Nakhijevan is an exclave bordered by Armenia, Iran and a ten kilometre frontier with Turkey. Zangezur, the territory that separates mainland Azerbaijan from Nakhijevan,was kept as part of Armenia. This was the last bit of the independent republic which fell to the Soviets in July 1921. Subsequently it became an integral part of Soviet Armenia.[24]

In the following years, three separate republics existed, but turmoil continued, mainly as the Dashnaks pursued their irredentist claims on their neighbours. They had territorial claims on both Georgia (the Akhalkalaki and Gocharli regions which are still today predominantly Armenian-populated) and Azerbaijan (Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan). Thus, far from being peaceful, this era was characterized by inter-ethnic strife. By 1919, however, the Dashnaks had been driven out of Nakhchivan, and although they stayed in power in Zangezur until 1921, they were soon toppled in Yerevan as well.[25]

In December 1920 the revolutionary committee of Soviet Azerbaijan, under Soviet pressure from central authorities, issued a statement that Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan were all to be transferred to Armenian control. Stalin (then commissar for nationalities) publicised the decision on 2 December, but the Azerbaijani leader Narimanov later denied the transfer. Four months later, the pendulum swung back. The ‘Treaty of Brotherhood and Friendship’ between the Soviet Union and republican Turkey included a provision that both Nakhchivan and Karabakh were to be placed under the control of the Azerbaijani SSR. It appears that this was a concession on the part of the Bolsheviks to the newly founded Turkish republic in Ankara—Lenin and Stalin were initially positively inclined to Kemal Atatiirk, whom they saw as a potential ally at the time. Atatiirk was hostile to any territorial arrangements favouring Soviet Armenia, since a strong Armenia could have potential territorial claims on Turkey. Even given Stalin’s tendency to divide the Caucasian peoples to prevent unified resistance,51 the idea of separating the Armenians into two entities—an Armenian republic and Nagorno-Karabakh— must have been welcome. Furthermore, this decision not only divided the Armenians but also the Azeris, into the Azerbaijani republic and Nakhchivan.[26]

n 1924, Nakhchivan received the status of an autonomous republic (ASSR) within the Azerbaijani SSR, despite the fact that the region had no land connection with mainland Azerbaijan. Nakhchivan’s belonging to the Azerbaijani republic was actually decided at the same time as the discussions on Nagorno-Karabakh. Nakhchivan’s status was, it seems, decided in talks between Soviet Russia and Kemalist Turkey, without involving any Armenians, at the treaty of Moscow in March 1921. This treaty stipulated that Nakhchivan would remain an autonomous region of Azerbaijan, and that the region’s status could not be altered without Turkey’s explicit approval.54 It is clear that this deal was clinched by Turkey in view of Ankara’s military offensive in the Caucasus immediately following the Ottoman signing of the Sevres treaty in August 1920.[27]

In retrospect, this decision may have been to Azerbaijan’s immediate favour, but in the long run the Armenians’ feeling of frustration with the loss of western Armenia despite Western promises, and the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan, despite Soviet promises, proved to have a catalytic effect.[28]

In August 1920 the Treaty of Sevres was signed, in which Woodrow Wilson himself had drawn the boundaries of a future Armenian state. This state was designed to include portions of Eastern Anatolia, or what Armenians call Western Armenia. Moreover, it was designed to include Nakhchivan—despite its predominantly Turkic population—as well as most of the NKAO.[28]

Thus, once under Soviet rule, it became the persistent aim of Armenian elites to reverse the situation and persuade Moscow to turn Karabakh over to the Armenian SSR. It has to be noted, at this point, that the Soviet decision was actually quite arbitrary in several ways. Firstly, Nakhchivan received the status of an ASSR, and there is no reason why Nagorno-Karabakh should not have been eligible for the same status. In fact, an arrangement in which the status of these two regions would have paralleled each other (such as a Nakhchivan ASSR under the Azerbaijani SSR, and a Nagorno-Karabakh ASSR under the Armenian SSR or vice-versa) would indeed have been more logically persuasive and would have helped to prevent rather than catalyze future conflict. A counter to this claim, is that according to the Azeris, there are sizable Azeri minorities in Armenia and Georgia as well as in Dagestan (especially in the Derbent region) which did not receive any autonomous status at all although geographically these populations are geographically concentrated in specific areas. The loss of Derbent is particularly inexplicable to the Azeris, who claim that it in this context it was not evident that the Armenians in Karabakh would even receive autonomous status. Nakhchivan is not encircled by Armenia, as Nagorno-Karabakh is encircled by Azerbaijan: Nakhchivan has a border with Turkey (if only seven kilometres)57 as well with Iran.[28]

there was no other case of an autonomous region or republic whose titular nationality is the same as the central state’s titular nationality, as is the case with Nakhchivan.[29]

The border between Nakhchivan and Turkey did not exist at the creation of the Nakhchivan AR but came into existence due to a border alteration in the 1930s between Turkey and Iran which granted Turkey this border but according to which Iran was compensated further south for this territorial loss. The border alteration was undertaken due to a Turkish initiative with precisely this aim in mind.[30]

Sovietization and Soviet period[edit]

http://lraber.asj-oa.am/3619/ Из истории деарменизации Нахичеванского края (1920—1921 гг.)

Aleksanyan, Hovhannes (2017). "Հայերը Նախիջևանի ԻԽՍՀ-ում 1945–1988 թթ. հայաթափության և մշակութային բնաջնջման ադրբեջանական քաղաքականությունը [Armenians in Nakhijevan ASSR in 1945–1988: The Azerbaijani Policy of Ethnic Depopulation and Cultural Destruction of Armenians]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1): 65–78.

Vazgen I's efforts[31]

Այնուհետեւ նույն հատուկ քաղաքականության հետեւանքով հայերի թիվը տարիների ընթացքում ավելի ու ավելի նվազեց, իսկ 1988թ. նոյեմբերյան դեպքերի նախօրյակին կազմում էր ընդամենը 1,5 տոկոս։ Կես տոկոսը կազմում էին Նախիջեւան, Ջուլֆա քաղաքներում եւ պատմական Գողթն գավառի տարածքի շուրջ մեկ տասնյակ գյուղերում պահպանված հայության բեկորները (շուրջ 1200 մարդ), իսկ մոտ մեկ տոկոսը (մոտ 2000 մարդ՝ շուրջ 450 ընտանիք) բնակվում էր պահպանված միակ հայաբնակ խոշոր բնակավայրում՝ Ազնաբերդ գյուղում։ [32]

The second point is the popular perception emanating from these figures—especially the figures that showed the exodus of Armenians from their historic lands. In this context the experience of Nakhijevan became the paradigm. Whereas the Armenian population in this region was slightly less than 50 per cent at the time of its Sovietisation, by the 1980s it was around 1–2 per cent. Armenians used the term ‘Nakhijevanisation’ to denote the depopulation of Armenians from historic Armenia. Mountainous Gharabagh was constantly cited as the ‘next Nakhijevan’ if the trend was not stopped. Armenians pointed out that in the regions under Azerbaijani jurisdiction the Armenian population declined steadily in favour of the Azerbaijanis. Of course they did not mention the similar process taking place in Armenia in favour of the Armenians. The ‘Nakhijevanisation’ argument, and the demographic trend it symbolised, was a powerful impetus in the 1988 Gharabagh movement.55 For example, Artashes Shahpazian made this point very clearly (author’s interview). Some nationalists also use the ‘Nakhijevan paradigm’ with reference to Javakh, the Armenian region in southern Georgia (where some 100,000 Armenians live).[33]

Unconnected to them, the second wave began on 24 April 1966 in the home of Sergei Khachatrian, its main leader being his brother, Haikaz.10 It was more organised, and a secret ‘party’was founded called Azgayin Miatsial Kusaktsutiun (National Unity Party [NUP]). It actually managed to publish a single issue of a paper called Paros (Lighthouse). It too was based on the land issue and a sense of betrayal that the Soviet regime was not, at the very least, transferring Nakhijevan, Gharabagh and Javakh to Armenia,[34]

Whatever conclusion can be drawn from the territorial delimitation, already by the 1930s the Armenians were attempting to regain control over both NagornoKarabakh and Nakhchivan, at a time when a number of territories saw their status changed from above, such as Abkhazia’s relation to Georgia.[29]

In 1979, a census recorded that, of the population of Karabakh 79 per cent were Armenian, whereas in 1939 they had composed 91 per cent of the population. The Armenians blamed the change on the Azerbaijani government, claiming that the Azeris were intentionally trying to manipulate the demography of the region, as they claimed had been done in Nakhchivan, where Armenians had represented 15 per cent in the 1920s, reduced now to only 1.4 per cent.[35]

http://articles.latimes.com/1990-01-21/news/mn-1001_1_soviet-union The announcement, which followed a broadcast of martial music, appealed for outside powers to "prevent a massacre of the people" in the capital city, the scene of clashes between Soviet Azerbaijanis and the Armenian minority early this month.

Karabakh conflict and Nakhchivan[edit]

The number of sporadic incidents grew quickly from 1987 onwards, letters demanding unification starting to flow in to the Moscow authorities. In August of 1987, a petition prepared by the Armenian academy of sciences with hundreds of thousand signatures (in Armenia) requested the transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan (where a 1979 census had recorded over 97 per cent Azeris)62 to the Armenian SSR.63[35]

1988 A state of emergency was declared in Baku, Ganja and Nakhchivan on 26 November,119 and a curfew in Yerevan on 25 November. Later that month, the last Azeris were forced out of Armenia.[36]

1989 July In another development that month, Armenia implemented an embargo against Nakhchivan, and the newly formed APF responded by setting up an embargo against the whole of Armenia, which was badly hit by this development as over two-thirds of Armenia’s goods came through Azerbaijan.138 Thus Armenia’s decision to try to isolate Nakhchivan seems to have been, to say the least, less than carefully examined.[37]

May 1992

Gelb, Leslie H. (22 May 1992). "Foreign Affairs; War in Nakhichevan". New York Times.

Randolph, Eleanor (20 May 1992). "Iran, Turkey Denounce Armenian 'Aggression'". Washington Post.

Goldberg, Carey (21 May 1992). "Moscow Sees War Threat if Outsiders Act in Karabakh". Los Angeles Times.

"Armenians, Azerbaijanis battle under shadow of Mount Ararat". Racine Journal Times via AP. 23 May 1992.

https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20030709_IB92109_040563c72e8a3154cf3834fbf6e8952da3e0040b.pdf

Congressional Research Service

Many Armenians declare unity of Armenia and Karabakh ineluctable. They assume that Azerbaijan intends to oust them from Karabakh, the way they believe it did from Nakhichevan in the 1920s.

Turmoil in Baku provided opportunities for Armenians, who took Shusha, the last Azeri town in Karabakh on May 9. Armenians then secured Lachin to form a corridor joining Armenia and Karabakh. The fall of Shusha provoked a political crisis in Baku in which the government changed twice in 24 hours. During this melee, Armenians appeared to launch an offensive against Nakhichevan in which 30,000 people were displaced. International attention focused on the conflict. Turkey and Iran denounced Armenian “aggression” and the U.S. State Department issued a strong statement. NATO, the European Community, and the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) declared that violations of territorial integrity and use of force were not acceptable.

In May 1992, Armenians forcibly gained control over Karabakh and appeared to attack the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic, an Azeri enclave separated from Azerbaijan by Armenian territory. Fear of possible action by Turkey, Russia, and others led to demands for action by the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) and the United Nations. All neighboring nations remain involved or concerned.

The two presidents met with President Chirac again in Paris, March 4-5. In June 2002, Aliyev revealed that, during these talks, it was agreed that Azerbaijan would cede control of Nagorno Karabakh and the Lachin corridor to Armenia in exchange for Armenia’s withdrawal from areas around Karabakh and a corridor through Armenia’s Meghri region, which borders Iran, to link Azerbaijan’s Nakhichevan region and the rest of Azerbaijan. But, he claimed, Armenia reneged. Kocharian denied agreeing to cede sovereignty over a Meghri corridor, but admitted that allowing Azerbaijan “unfettered access” via Meghri had been discussed.

In fact, immediately before acceding to power, Aliyev was the leader of Nakhchivan, the Azerbaijani enclave encircled by Armenia, Iran and Turkey. During the war, Aliyev had ruled Nakhchivan autonomously from Baku and had established good personal relations with Iranian leaders, unilaterally concluding several trade and energy deals with Iran without seeking Elchibey’s approval. In fact, Iran gave financial aid to Nakhchivan and put pressure on Armenia to refrain from attacking the enclave—something which clearly could have led to an escalation of the conflict, as Turkey considers itself a guarantor of Nakhchivan’s security by its 1921 treaties with the Soviet Union. [38]

Since the conflict erupted into war in 1992, Iran has attempted to exert its influence on Azerbaijan. For the most part, this has meant working against Azerbaijan through support for Armenia. This has, however, not always been the case. When the conflict threatened to spill over into Iran, Tehran actually raised its tone against the Armenians. It made a joint appeal with Turkey to the UN Security Council to condemn the Armenian aggression. Hence it seemed as if Tehran was becoming aware of the danger of a collapse in Azerbaijan, which could have important implications for regional security.56 At several points, Iran made clear that it sought to preserve the existing balance of power in the region. Here again, the Nakhchivan enclave was perceived to be of crucial importance. When Nakhchivan was under threat of an Armenian attack in September 1993, Iranian troops crossed the river Araxes, prompting a strong Russian reaction. Russia made it clear that good relations with Iran are conditional on Iran’s acceptance of Russian supremacy in the Caucasus. Nevertheless, Iran’s action was enough to intimidate Armenia; the Armenian foreign minister assured Tehran that there would be no more attacks on Nakhchivan.5[39]

SIPRI: In February fear that the war over Nagorno-Karabakh would cross international borders mounted as the Turkish 3rd Field Army began conducting large manceuvres close to the border of the Azerbaijani region of Nakhichevan. The prospect of the former Soviet 4th Army in Armenia or the former Soviet 7th Army in Azerbaijan coming into direct contact with Turkish armed forces, that is, the prospect of a NATO country becoming more closely involved, did not seem too far-fetched since Nakhichevan had previously been subjected to military raids by Armenia.[2]

Turkey tried to avoid an open confrontation with the Russian Federation, but the Karabakh war forced Ankara to choose sides. In 1993, Prime Minister Tansu Ciller, invoking the 1921 Kars Treaty, even declared that if Armenian forces entered Nakhchivan, Turkey would have no option but to respond (Harris 1995).

http://biweekly.ada.edu.az/vol_4_no_13/Azerbaijan_and_the_revision_of_Turkey_regional_policy.htm

Harris, George S. (1995) “The Russian Federation and Turkey”, in Alvin Z. Rubinstein, ed., Regional Power Rivalries in the New Eurasia: Russia, Turkey and Iran (Armonk, NY).

http://www.aniarc.am/2020/12/26/armenia-nakhijevan-turkey-1992-book-chapter/ 1992

Post-war developments[edit]

Land swap proposal[edit]

2010s[edit]

2010s Sanamyan, Emil (24 March 2018). "Nakhichevan Remains the Quietest Stretch of Armenian-Azerbaijani Frontline". civilnet.am. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

While there were some redeployments made in the direction of Nakhichevan, specifically in the area southwest of Sisian, the area in question is roughly between 10 and 20 square kilometers (or 1,000 to 2,000 hectares).

If the question is about territorial changes in Sisian or Mrav areas compared to the outcome of the April war of 2016, then the positions in Sisian and on Mrav are on higher elevation and one could say more strategic, giving Armenian units a largely unencumbered view of the towns of Nakhichevan and Ganja, whereas the hills captured by Azerbaijanis near Talish and Horadiz are of more tactical significance.

On Nakhichevan border, specifically, there was no serious fighting after May 1992, because at the time the leader of Nakhichevan, Heydar Aliyev, agreed to a separate cease-fire with the Armenian government. On the other side of the Syunik border, there was serious fighting and bombing by Azerbaijan – particularly of Kapan – until 1993, when adjacent Azerbaijani districts were captured. Since 1994, you had, on one hand de-militarization of eastern side of Syunik, and on the other, militarization of Armenia-Nakhichevan border., However, to this day Nakhichevan remains the quietest stretch of Armenian-Azerbaijani frontline in part because of the high altitude of most of the border, and in part because of the political decision by Azerbaijani leadership not to escalate tensions there.

Sanamyan, Emil (1 June 2018). "Azerbaijan makes a move in Nakhichevan amid change of guard in Armenia". civilnet.am. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

http://asbarez.com/124663/armenian-army-fortifies-positions-at-nakhichevan-border/

Goble, Paul (12 June 2018). "Nakhchivan Again Site of Broader and More Dangerous Geopolitical Competition". Jamestown Foundation.

...............[40]

Armenian monuments[edit]

Argam Aivazian Նախիջևանի կոթողային հուշարձաններն ու պատկերաքանդակները

List of Armenian churches in Azerbaijan

https://hyperallergic.com/482353/a-regime-conceals-its-erasure-of-indigenous-armenian-culture/ A Regime Conceals Its Erasure of Indigenous Armenian Culture

Vanished: @Cornell’s Caucasus Heritage Watch (@CaucasusHW) compiled decades of high-res satellite imagery to document the complete destruction of Armenian cultural heritage in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan. @CornellCAS @LifeAtPurdue https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2022/09/report-shows-near-total-erasure-armenian-heritage-sites

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/06/01/special-investigation-declassified-satellite-images-show-erasure-of-armenian-churches Special investigation: Declassified satellite images show erasure of Armenian churches

Khatchadourian, Lori; Smith, Adam T.; Ghulyan, Husik; Lindsay, Ian (2022). Silent Erasure: A Satellite Investigation of the Destruction of Armenian Heritage in Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan. Cornell Institute of Archaeology and Material Studies: Ithaca, NY. pp. 188–191. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2022.

https://www.mfa.am/en/speeches/2023/11/09/Mirzoyan_UNESCO/12315 Deployment of UNESCO's independent fact-finding mission to Nagorno-Karabakh with the view of independent monitoring and mapping of the Armenian cultural heritage is a key prerequisite to prevent destruction or distortion of the Armenian cultural property, as was the case with the complete annihilation of the Armenian cultural heritage in Nakhijevan between 1997-2006.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24049285 Reviewed Work: The Historical Monuments of Nakhichevan by ARGAM AYVASIAN, Krikor H. Maksoudian J. M. Rogers

Armenian perspectives and claims[edit]

Although no Armenians remain in Nakhchivan in the 21st century, the Armenian society continues to view Nakhchivan as an "inherent part of Armenian cultural and historical heritage—much like Karabakh."[40]

At a panel discussion with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in the sidelines of the 2020 Munich Security Conference, Armenia's Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated: "We also remember the fate of Nakhichevan, where there was a huge Armenian population. Nakhichevan is an autonomous republic within Azerbaijan, and now there is no Armenian there."[41]

https://www.primeminister.am/hy/interviews-and-press-conferences/item/2023/12/19/Nikol-Pashinyan-Interview-Petros-Ghazaryan/ Իհարկե, մենք դրան կարող ենք ասել Նախիջևանի հայերի վերադարձի իրավունքը

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun), the most influential Armenian nationalist party, claims Nakhchivan as part of United Armenia, along with Karabakh (Artsakh), Western Armenia, and Javakheti (Javakhk).[42][43][44]

During the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, American-born Armenian military commander Monte Melkonian, who was killed in 1993, stated: "There's bound to be a coup d'etat in Turkey sometime in the next 10 years. During the immediate post-coup chaos, we'll take Nakhichevan—easy!"[45]

Rəfael Hüseynov, the Director of the Nizami Museum of Azerbaijani Literature, in his written question to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in 2007 claimed that the "seizure Nakhichevan is one of the main military goals of Armenia."[46] Writing in the Harvard International Review in 2011 US-based Azerbaijani historian Alec Rasizade suggested that "Armenian ideologues have lately started to talk about the return of Nakhichevan."[47]

At various occasions, Armenian nationalist activists and groups have advocated annexing Nakhchivan, especially in case of a possible Azerbaijani aggression. Jirair Sefilian, a Karabakh war veteran and politician, stated in a 2007 interview that Armenia should lay claims to the region. He referred to the destruction of Julfa khachkars as a justification for an invasion. Calling the Azerbaijani population "new comers," he insisted that they will not be forced to leave their homes. Instead, the Azerabaijani forces would leave and be replaced with Armenian ones. An Armenian rule would be instated over the region not only to restore "historical justice," but also to ensure "best conditions for the free market between Armenia and Iran."[48] Raffi Hovannisian, former foreign minister of Armenia and leader of the liberal nationalist Heritage party, has hinted at Western Armenia, Javakhk and Nakhichevan with "vague formulations."[49] The youth wing of Heritage Party in 2009[50] and the minor extra-parliamentary nationalist party Hayazn in 2013[51] advocated "liberation" of Nakhchivan in case of a major Azerbaijani attack from that direction. Similar views have been expressed by historian Ara Gasparyan (2018),[52] former diplomat Ara Papian (2020)[53] and others.

Notable Armenians from Nakhchivan[edit]

- Matteos Jughayetsi (born 1350), scribe

- Azaria Jughayetsi (1534–1601), Armenian Catholicos of Cilicia between 1584 and 1601[54]

- Hakob Jughayetsi (1598–1680), Catholicos of All Armenians between 1655 and 1680, from Jugha (now Julfa)[55]

- Azaria Jahketsi, Armenian Catholic priest

- Alexander Jughayetsi (died 1714), Catholicos of All Armenians (1706–1714)[56]

- Shemavon of Agulis, Safavid official

- Naghash Hovnatan (1661–1722), the patriarch of the Hovnatanian (17th–19th centuries), a family of painters originally from Shurut village[57][58]

- Ghazar Jahketsi, Catholicos of All Armenians (1737–1751)

- Jean Althen

- 19th century

- Hovhannes Shahkhatuniants (1799-1849), Armenian bishop

- Christapor Mikaelian (1859–1905), one of the three founders of the ARF, born in Agulis village[59]

- Stepan Sapah-Gulian (1861–1928), intellectual and leader of Social Democrat Hunchakian Party born in Djahri village

- Manuk Abeghian (1865–1944), scholar of literature and folklore, born in Astabad village[60]

- Stepan Zorian (1867–1919), one of the three founders of the ARF, born in Tsghna village[61]

- Mikayel Manvelian (1877-1944), actor, playwright

- Vardan Mirzoyan (1877-1968), actor

- Khetcho (1872–1915), Armenian fighter

- Hasmik (Taguhi Hakobyan, 1878-1947) born in Nakhichevan city

- Ruben Orbeli (1880-1943), archaeologist

- Garegin Nzhdeh (1886–1955), military commander, statesman, born in Kznut village[62]

- Khachik Mughdusi (1895-1938), Bolshevik, head of the Armenian NKVD during the Stalinist purges

- Yakov Davydov (1888–1938), Soviet official, born in Verin Agulis[63]

- Gaik Ovakimian (1898-1967), Soviet spy

- 20th century

- Grigor Vahramian Gasparbeg (1900-1963), painter

- Aram Merangulian (1902-1967), composer

- Hripsime Djanpoladjian, parents from Nakhichevan ru:Джанполадян-Пиотровская,_Рипсимэ_Микаэловна#cite_ref-AN_1-0

- Vladimir Sargsyan (1935–2013), mathematician

- Argam Aivazian (b. 1947), historian and researcher, born in Arinj village[64]

- Artak Vardanyan (b. 1951), writer and philologist

- Aghvan Vardanyan (b. 1958), ARF politician, born in Gömür village[65]

Aram Khachaturian

Komitas

Fadey Sargsyan

https://archive.ph/NppVY

https://www.aravot.am/2023/06/09/1346817/

ՀՀ ԳԱԱ նախկին նախագահ Ֆադեյ Սարգսյանը, որ հոր եւ մոր կողմից սերվում էր Ազայից ոչ հեռու գտնվող՝ Նախիջեւանի Կզնուտ գյուղից

sources[edit]

-

1887

-

1902

-

1880

-

1926

https://twitter.com/ArtyomTonoyan/status/1243916029190955011 1970 Soviet map

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

p. 266

http://echmiadzin.asj-oa.am/11549/ Գողթնի 1919 թ. ինքնապաշտպանությունը

http://hpj.asj-oa.am/5284/ Այդ պատճառով է/ միայն Նախիջևանում 1926 թ. մարդահամարի տվյալներով 1917 թ. համեմատությամբ հայ բն ակչություն ը պակասեց 5 անգամ։ Հին հայկական Նախիջևանի նահանգում 1917 թ. ապրում էր 53,9 հազար հայ բնակչություն (ընղհանուրի 40 տոկոսը), իսկ 1926 թ. ընդամենը 11,3 հազար։

http://hpj.asj-oa.am/1619/

Հայ ազգաբնակչության տեղաբաշխումն Ադրբեջանական և Վրացական ԽՍՀ-ներում (1920-30-ական թվականներ)

http://www.raa-am.com/raa/public/publish.php?clear=1&mid=5&more=1&cont=79&obid=154

http://www.raa-am.com/raa/pdf_files/80.pdf

http://lraber.asj-oa.am/4119/ Արգամ Այվազյան, Նախիջևանի կոթողային հուշարձաններն ու պատկերաքանդակները, ՀՍՍՀ Մինիստրների խորհրդին առընթեր պատմության և կուլտուրայի հուշարձանների պահպանության ու օգտագործման գլխավոր վարչություն, Երևան, «Հայաստան» հրատարակչություն, 1987, 398 էջ, 459 լուսանկար։

http://haygirk.nla.am/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=53929

http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=61&dt=HY_HY&pageNumber=3015

http://www.raa-am.com/Naxigevan%20qartez/Atlas_E.pdf

http://lraber.asj-oa.am/4045/ Из истории армянского населения Нахичевана

A third point, although not at the core of the problem, is the fact that Azerbaijan is partitioned between mainland Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan. The two parts of the country have no territorial connection, and are separated by Zangezur, which belongs to mainland Armenia. Azerbaijan would naturally want to connect the two parts of the country, whereas Armenia does not want to give up any land, largely because that would cut off Armenia from Iran, one of its main trading partners, and encircle it even more in a hostile, Turkic world.[67]

As the Armenians argue that the Lachin corridor is a necessity for the security of Karabakh, one could imagine a mutual boundary change whereby Armenia is granted Karabakh and Lachin, thus establishing a land connection between the two entities; Azerbaijan would, as compensation, receive a land corridor to Nakhchivan, through Zangezur. Such a solution has the advantage of eliminating many potential future conflicts that may erupt due to the problems of communication between Armenia and Karabakh or between Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan.[68]

In practice, Ajar autonomy was probably granted in the context of Soviet Russia’s rapprochement with republican Turkey in the 1920s, which, as we have seen, influenced the Soviet leadership’s decisions on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan. Turkey, with its long history of rule over Ajaria, naturally was interested in the autonomy of the region on its border just as it was interested in Azerbaijani jurisdiction over Nakhchivan.[69]

In the south Caucasus, the 1921 treaties between the Soviet Union and the emerging Turkish republic created a map which brought conflict and dissent that has lasted up to the present day. Stalin actually managed to divide both the Armenian and Azeri peoples into non-contiguous territories, creating the Armenian enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh (an AO) completely encircled by Azerbaijan, and the Azeri enclave of Nakhchivan (an ASSR), cut off from mainland Azerbaijan by Armenia. Both entities were put under the jurisdiction of the Azerbaijani SSR.35[70]

References[edit]

- Notes

- References

- ^ a b c Vardanyan, Artak [in Armenian] (2017). "«Նախիջևան» տեղանվան ստուգաբանության շուրջ [On the Topnonym "Nakhijevan"]" (PDF). Conference Paper (in Armenian). Institute of Language of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-09.

- ^ Abrahamian, Levon (2006). Armenian Identity in a Changing World. Mazda Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 1-56859-185-3.

- ^ Dwight, H. G. O. (1856). "Armenian Traditions about Mt. Ararat". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 5. New York: 189–191. doi:10.2307/592222. JSTOR 592222.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus of the Antiquities of the Jews — Book I". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Fraser, John Foster (1925) [1899]. Round the World on a Wheel (5th ed.). London: Methuen. p. 90.

In time we reached Nachitchevan and visited Noah's tomb. It is a featureless, mud-covered building that the Armenians regard as holy.

- ^ a b c Massalski, Władysław [in Russian] (1897). "Нахичевань". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary Volume XXa (in Russian). pp. 704–705. online view

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, pp. 35, 45.

- ^ Gottheil, Richard; Rosenthal, Herman; Ginzberg, Louis (1906). "Armenia". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (1992). The Geography of Ananias of Širak. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 183, 191-192, 211.

- ^ Acharian, Hrachia (1984). Հայոց գրերը [The Armenian Letters] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. pp. 84–87.

- ^ Editorial (1980). "Հայ Եկեղեցու տոնելի սրբերի համառոտ կենսագրությունները [Biographies of celebrated saints of the Armenian Church]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 37 (11): 32–33.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, pp. 85, 104, 106.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, pp. 97, 130.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 143.

- ^ Hewsen 2001, p. 148.

- ^ Panossian 2006.

- ^ Panossian 2006, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Panossian 2006, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Panossian 2006, p. 221.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Panossian 2006, p. 245.

- ^ Panossian 2006, p. 249.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Cornell 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Cornell 2005, p. 62.

- ^ a b Cornell 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 410.

- ^ Amiryan, Serhak (2008). "Ամենայն Հայոց կաթողիկոս Վազգեն Առաջինը և խորհրդային իշխանությունները (Ծննդյան 100-ամյակի առթիվ) [Catholicos of All Armenians Vazgen the First and the Soviet Powers (to the 100th birth]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (2): 39–63.

- ^ Vardanyan, Artak (21 November 2013). "Նախիջեւանի վերջին ամրոցը [Nakhijevan's last fortress]". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 10 April 2018.

- ^ Panossian 2006, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Panossian 2006, p. 324.

- ^ a b Cornell 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 74.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 315.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 318.

- ^ a b Abrahamyan, Eduard (3 August 2017). "Armenia and Azerbaijan's Evolving Implicit Rivalry Over Nakhchivan". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018.

- ^ ""Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh ready to make real efforts to resolve the conflict" - Nikol Pashinyan attends panel discussion on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference". primeminister.am. The Office to the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia. 15 February 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020.

- ^ "Ծրագիր Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցության (1998) [Armenian Revolutionary Federation Program (1998)]" (in Armenian). Armenian Revolutionary Federation Website. 14 February 1998. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

ՀՅ Դաշնակցությունը նպատակադրում է. Ա. Ազատ, Անկախ եւ Միացյալ Հայաստանի կերտում: Միացյալ Հայաստանի սահմանների մեջ պիտի մտնեն Սեւրի դաշնագրով նախատեսված հայկական հողերը, ինչպես նաեւ` Արցախի, Ջավախքի եւ Նախիջեւանի երկրամասերը:

The goals of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation are: A. The creation of a Free, Independent and United Armenia. United Armenia should include inside its borders the Armenian lands [given to Armenia] by the Sevres Treaty, as well as Artsakh, Javakhk and Nakhichevan provinces. - ^ "Armenia: Internal Instability Ahead" (PDF). Yerevan/Brussels: International Crisis Group. 18 October 2004. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

The Dashnaktsutiun Party, which has a major following within the diaspora, states as its goals: "The creation of a Free, Independent, and United Armenia. The borders of United Armenia shall include all territories designated as Armenia by the Treaty of Sevres as well as the regions of Artzakh [the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh], Javakhk, and Nakhichevan".

- ^ Harutyunyan, Arus (2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-109-12012-7.

The ARF strives for the solution of the Armenian Cause and formation of the entire motherland with all Armenians. The party made it abundantly clear that historical justice will be achieved once ethnic Armenian repatriate to united Armenia, which in addition to its existing political boundaries would include Western Armenian territories (Eastern Turkey), Mountainous Karabagh and Nakhijevan (in Azerbaijan), and the Samtskhe-Javakheti region of the southern Georgia, bordering Armenia."

- ^ Rowell, Alexis (August 6, 1993). "Armenia's Push for Land". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023.

- ^ "The serious threats arising from Armenia's invasive plans towards the Autonomous Republic of Nakhichevan of Azerbaijan and the responsibility of the Council of Europe". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 27 June 2007. (archived)

- ^ Rasizade, Alec (18 January 2011). "Azerbaijan's Chances in the Karabakh Conflict". Harvard International Review. Archived from the original on 2017-02-26.

- ^ "Sefilian's Case: The Next Must be Nakhijevan" (PDF). Azg. 21 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018.

- ^ Abrahamyan, Aram (4 March 2013). "Raffi Hovhannisyan's Foreign Policy Agenda". Aravot. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

Mr. Hovhannisyan also hints at Nakhijevan, Western Armenia, and Javakhk with vague formulations...

- ^ "Խոստանում են ազատագրել Նախիջեւանը". A1plus (in Armenian). 27 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Հայազն Կուսակցության հայտարարությունը". lragir.am (in Armenian). 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018.

- ^ Gasparyan, Ara (4 October 2018). "Նախիջեւանի երեք հիմնախնդիրները եւ Նախիջեւանը հայկական պետությանը վերադարձնելու հավանական տարբերակը [The Three Porblems of Nakhichevan and the Possible Way to Return Nakhichevan to the Armenian State]". Aravot (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 17 May 2020.

Եթե փորձ արվի Նախիջեւանի տարածքը օգտագործել Հայաստանի դեմ ռազմական ագրեսիա իրականացնելու համար, ապա մենք ոչ միայն արդյունավետ դիմակայելու ենք, այլեւ դիտարկելու ենք Նախիջեւանը հայկական պետությանը վերադարձնելու տարբերակը: Այդ նպատակով արդեն իսկ պետք է սկսել ապահովել միջազգային իրավապայմանագրային, ռազմական, տնտեսական եւ բարոյահոգեբանական ոլորտներում անհրաժեշտ հիմքերը։

- ^ "Եթե այսօր մենք չլուծենք Նախիջևանի հարցը՝ վաղը թուրքերը Երևանը գերեզման կսարքեն. «Մոդուս վիվենդի»". lratvakan.am (in Armenian). 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020.

- ^ Parsumean-Tatoyean, Seda (2003). The Armenian Catholicosate from Cilicia to Antelias: An Introduction. Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. p. 113.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. xliv. ISBN 9780810874503.

- ^ Danielyan, Eduard L. (2009). Gandzasar Monastery. Yerevan: Gandzasar Theological Center. p. 34. ISBN 978-99930-70-03-0.

- ^ Ararat. 33. Armenian General Benevolent Union. 1992.

In Armenia we have Naghash Hovnatan— Jonathan the Painter. He was born in Shorot, in the district of Goghten, in 1661

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Akopian, Aram (2001). Armenians and the World: Yesterday and Today. Yerevan: Noyan Tapan. p. 131. ISBN 9789993051299.

- ^ Chalabian, Antranig (2009). Dro (Drastamat Kanayan): Armenia's First Defense Minister of the Modern Era. Los Angeles, CA: Indo-European Publishing, 2010. p. 129. ISBN 9781604440782.

- ^ Khachaturian, Lisa (2011). Cultivating Nationhood in Imperial Russia: The Periodical Press and the Formation of a Modern Armenian Identity. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 199. ISBN 9781412813723.

- ^ Chalabian, Antranig (1988). General Andranik and the Armenian Revolutionary Movement. p. 59.

Rostom (Stepan Zorian) was born in 1867 in Tsghna village (Goghtn district).

- ^ Holding, Nicholas (2008). Armenia: with Nagorno Karabagh : the Bradt travel guide. Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 190. ISBN 9781841621630.

- ^ Давыдов Яков Христофорович (in Russian). Foreign Intelligence Service. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ "Argam Ayvazyan" (in Armenian). ArmenianHouse.org. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "Aghvan Vardanyan". National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Hewsen 2001.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Cornell 2005, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Cornell 2005, p. 28.

- Bibliography

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231139267.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

- Cornell, Svante (2005). Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus (PDF). Routledge. ISBN 9781135796693.