User:Wikipedian1234/sandbox

Rockville, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| The Mayor and Council of Rockville[1] | |

Downtown Rockville in 2001, the Montgomery County Judicial Center in 2010, the Rockville Town Square in 2010, the Beall-Dawson House in 2005, and downtown Rockville in 2008. | |

| Motto: "Get Into It!"[2] | |

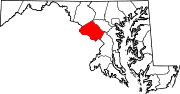

Location in the U.S. state of Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°5′1″N 77°8′54″W / 39.08361°N 77.14833°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Settled | 1717 |

| Founded | 1803 |

| Incorporated | 1860 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bridget Donnell Newton (I)[3] |

| Area | |

| • City | 13.57 sq mi (35.15 km2) |

| • Land | 13.51 sq mi (34.99 km2) |

| • Water | 0.06 sq mi (0.16 km2) |

| Elevation | 451 ft (137 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 61,209 |

| • Estimate (2014)[6] | 65,937 |

| • Density | 4,530.6/sq mi (1,749.3/km2) |

| • Metro | 5,306,565 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-67675 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0586901 |

| Website | www.RockvilleMD.gov |

Rockville is a city located in the central region of Montgomery County, Maryland. It is the county seat and is a major incorporated city of Montgomery County and forms part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. The 2010 census tabulated the Rockville's population at 61,209, making it the third largest incorporated city in Maryland, behind Baltimore and Frederick. Rockville is the largest incorporated city in Montgomery County, Maryland, although the nearby census-designated place of Germantown is more populous.[7]

Rockville, along with neighboring Gaithersburg and Bethesda, is at the core of the Interstate 270 Technology Corridor which is home to numerous software and biotechnology companies as well as several federal government institutions. The city also has several upscale regional shopping centers and is one of the major retail hubs in Montgomery County.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Situated in the Piedmont region and crossed by three creeks (Rock Creek, Cabin John Creek, and Watts Branch), Rockville provided an excellent refuge for semi-nomadic Native Americans as early as 8000 BC.[8] By the first millennium BC, a few of these groups had settled down into year-round agricultural communities that exploited the native flora, including sunflowers and marsh elder.[9] Beginning around 1200 AD, these early groups (dubbed Montgomery Indians by later archaeologists) were increasingly drawn into conflict with the Senecas and Susquehannocks who had migrated south from Pennsylvania and New York. This resulted in the Montgomery Indian’s gradual displacement over the next 300 years. By the arrival of European explorers in the early 17th century, the Montgomery people had mostly migrated to southern Maryland and joined the Piscataway Confederacy.[10] Under pressure from European colonists, remaining Indians in Montgomery County had been driven away by 1700.[10] Within the present-day boundaries of Rockville, six prehistoric sites of these people have been uncovered and documented, and borne artifacts several thousand years old.[10]

The indigenous population carved a path on the high ground, which was known by several names including the Sinequa Trail, the Rock Creek Main Road, and the Great Road.[9] The location of the road, today's Maryland Route 335, was strategically located on higher ground making it dry year-round.[11] Later, the Maryland Assembly set the standard of 20 feet for main thoroughfares and requested the Great Road to be built to this standard.[10] In the mid-18th century, Lawrence Owen opened a small inn on the road. The place, known as Owen's Ordinary, took on greater prominence when, on April 14, 1755, Major General Edward Braddock stopped at Owen's Ordinary while traversing the Great Road to press British claims of the western frontier.

18th century[edit]

The first land patents in the Rockville area were obtained by Arthur Nelson between 1717 and 1735. Within 30 years, the first permanent buildings in what would become the center of Rockville were established on this land.[12] Still a part of Prince George's County at this time, the growth of Daniel Dulaney's Frederick Town to the north prompted the separation of the western portion of the county, including the Rockville area, into Frederick County in 1748.[13]

Being a small, unincorporated community, early Rockville was known by several names, including Owen's Ordinary, Hungerford's Tavern, and Daley's Tavern. The first recorded mention of the settlement which would later become known as Rockville dates to the Braddock Expedition in 1755. On April 14, one of the approximately two thousand men who were accompanying General Braddock through wrote the following: "we marched to larance Owings or Owings Oardianary, a Single House, it being 18 miles and very dirty."[14] Owen's Ordinary was a small rest stop on the Rock Creek Main Road, which stretched from George Town to Frederick Town, and was then one of the largest thoroughfares in the colony of Maryland.

By the 1760s, Owen’s Ordinary had closed and was replaced by Thomas Davis’s inn and Charles Hungerford’s tavern.[13] Eventually, the village was referred to as Hungerford’s Tavern after the latter establishment. Shortly before the American Revolution, Hungerford’s Tavern was the location of the Hungerford Resolves of 1774, where on July 11 local planters declared their solidarity with protesters in Boston after the implementation of the Intolerable Acts.[15] Dr. Thomas Sprigg Wootton, one of the two chairs of the resolves, later went on to become the first Speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates in 1777.[16]

On September 6, 1776, the Maryland Constitutional Convention agreed to a proposal introduced by Thomas Sprigg Wootton wherein Frederick County, the largest and most populous county in Maryland, would be divided into three smaller units.[17] The southern portion of the county, of which Rockville was a part, was named Montgomery County. The most populous and prosperous urban center in this new county was Georgetown, but its location at the far southern edge rendered it worthless as a seat of local government. Hungerford’s Tavern, a small, but centrally located and well-traveled village, was chosen as the seat of the county's government.[17] After being named the county seat, the village was referred to as Montgomery Court House.[18] The tavern served as the temporary county courthouse, and it held its first such proceedings on May 20, 1777. A two-story brick building was constructed near the tavern in 1788 to serve as the new courthouse, along with a jail in 1801.[19]

In 1784, William Prather Williams, a local landowner, hired a surveyor to lay out the original town core. In his honor, many took to calling the town Williamsburgh. In practice, however, Williamsburgh and Montgomery Court House were used interchangeably.[19]

19th century[edit]

In 1800, Georgetown was ceded to the District of Columbia, making Rockville the largest settlement in Montgomery County at about 150 residents.[20] Proprietors of Williamsburgh plots became uneasy about the legal status of their property, as William William’s layout had never been officially recorded in Montgomery County’s land records. Landowners petitioned to the General Assembly regarding the issue, and in 1801 the Assembly passed an act to “survey, mark, bound and erect into a town” Williams’s land.[20] The area was officially entered into the county land records on July 16, 1803, with the name "Rockville," most likely derived from Rock Creek.[21] Nevertheless, the name Montgomery Court House continued to appear on maps and other documents through the 1820s. In 1805, the General Assembly chartered the Washington Turnpike Company to reinforce the existing Great Road to be reconstructed with macadam. The thoroughfare, soon known as Rockville Pike, remained poorly maintained despite this reconstruction, slowing Rockville’s growth significantly until the arrival of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in the 1860s.[22] The first postmaster was appointed in 1813 and the Rockville Academy, a private secondary school, was established in town in 1812.[23]

Shortly after the Burning of Washington during the War of 1812, Brigadier General William H. Winder and his troops, retreating from Washington, arrived at Rockville along Great Falls Road. There they encamped on the night of August 25, searching for food and other supplies.[24] Winder and his troops left the next day around noon. President James Madison, who had escaped the British assault on Washington, arrived in Rockville at 6 in the evening that same day in an attempt to reconnect with Winder, who had already begun marching to Baltimore[24]

Civil War[edit]

By 1860, Rockville’s population had grown to 365 and the number of the town's improved properties had doubled to around 90.[25][26] On March 10 of that year, the Maryland General Assembly incorporated the village in response to a local petition.[27] During the subsequent American Civil War, local sentiments tended towards the Confederate cause. Rockville's central position within Montgomery County and proximity to Washington rendered it strategically important to regional Union commanders. In June 1861, Union soldiers under Charles Pomeroy Stone successfully disarmed the Rockville Riflemen, a local pro-South militia,[28] arrested anti-Unionists, and seized Southern sympathizers’ weapons.[28] A Union camp was established at the end of June near Rockville Pike. The Union Army maintained a presence in Rockville throughout the war, entrusting a provost marshal with the surveillance of pro-South residents and the suppression of Union disloyalty.[29] 10 days before the Battle of Antietam, Union General George B. McClellan briefly stayed at the Beall-Dawson house while establishing headquarters in Rockville. Wounded soldiers from both sides at Antietam were delivered to Rockville via horse-drawn ambulances, with the courthouse and houses serving as hospitals.[30]

On June 28, 1863, General J.E.B. Stuart and an army of 8,000 Confederate cavalrymen briefly occupied Rockville [31] while on their way to Gettysburg; they took horses, captured over 170 Union wagons, and imprisoned several vocal Unionist, who were later released in Brookville.[32] In July 1864, Confederate General Jubal Anderson Early sent Brigadier General John McCausland's cavalry towards Rockville while on his way to pose an attack on Washington. Union lines under Major William Fry assembled a mile north of Rockville and on Commerce Lane. The forces clashed on July 10, resulting the Fry’s retreat after McCausland summoned artillery. Early marched through Rockville the next morning[33] After losing the Battle of Fort Stevens, Early returned briefly to Rockville on July 13, thereafter crossing the Potomac River to Virginia. Colonel Charles Russell Lowell, stationed with eight hundred cavalry near Saint Mary’s Church, moved his force into Rockville to reclaim it for the Union. Once Early learned that Rockville had been retaken, he sent General Bradley Johnson to drive Lowell back. An intense skirmish ensued in the middle of town, and an outnumbered Lowell was forced to retreat down Rockville Pike. During the short battle, Rockville’s town records were destroyed.[34] A monument to the Confederate soldier is hidden behind the old courthouse building[35][36] The monument was dedicated on June 3, 1913 at a cost of $3,600.

In 1873, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad arrived, making Rockville easily accessible from Washington, D.C. (See Metropolitan Branch.) In July 1891, the Tennallytown and Rockville Railway inaugurated Rockville's first trolley service connecting to the Georgetown and Tennallytown Railway terminus at Western Avenue and Wisconsin Avenue.

Twentieth century through today[edit]

The newly opened railroad provided service from Georgetown to Rockville, connecting Rockville to Washington, D.C. by trolley. Trolley service operated for four decades, until, eclipsed by the growing popularity of the automobile, service was halted in August 1935. The Blue Ridge Transportation Company provided bus service for Rockville and Montgomery County from 1924 through 1955. After 1955, Rockville would not see a concerted effort to develop a public transportation infrastructure until the 1970s, when the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) began work to extend the Washington Metro into Rockville and extended Metrobus service into Montgomery County. The Rockville station of Washington Metro began service on July 25, 1984, and the Twinbrook station began service on December 15, 1984. Metrobus service was supplemented by Montgomery County's own Ride On bus service starting in 1979. MARC, Maryland's Rail Commuter service, serves Rockville with its Brunswick line. From Rockville MARC provides service to Union Station in Washington D.C. (southbound) and, Frederick and Martinsburg, West Virginia (northbound), as well as intermediate points. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service from Rockville to Chicago and Washington D.C.

The mid-20th century saw substantial growth in Rockville, especially with the annexation of the Twinbrook subdivision in 1949, which added hundreds of new homes and thousands of new residents to the city. In 1954, Congressional Airport closed, and its land was sold to developers to build residences and a commercial shopping center.[37] The shopping center, named Congressional Plaza, opened in 1958.[38] These new areas provided affordable housing and grew quickly with young families eager to start their lives following World War II.

During the Cold War, it was considered safer to remain in Rockville than to evacuate during a hypothetical nuclear attack on Washington, D.C. Bomb shelters were built, including the largest one at Glenview Mansion and 15 other locations. The I-270 highway was designated as an emergency aircraft landing strip. Two Nike missile launcher sites were located on Muddy Branch and Snouffer School Roads until the mid-1970s.[39]: 163

From the 1960s, Rockville's town center, formerly one of the area's commercial centers, suffered from a period of decline. Rockville soon became the first city in Maryland to enter into a government funded urban renewal program. This resulted in the demolition of most of the original business district. Included in the plan was the unsuccessful Rockville Mall, which failed to attract either major retailers or customers and was demolished in 1994, various government buildings such as the new Montgomery County Judicial Center, and a reorganization of the road plan near the Courthouse. Unfortunately, the once-promising plan was for the most part a disappointment. Although efforts to restore the town center continue, the majority of the city's economic activity has since relocated along Rockville Pike (MD Route 355/Wisconsin Avenue). In 2004, Rockville Mayor Larry Giammo announced plans to renovate the Rockville Town Square, including building new stores and housing and relocating the city's library. In the past year, the new Rockville Town Center has been transformed and includes a number of boutique-like stores, restaurants, condominiums and apartments, as well as stages, fountains and the Rockville Library.[40] The headquarters of the U.S. Public Health Service is on Montrose Road while the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission's headquarters is just south of the City's corporate limits.

The city is closely associated with the neighboring towns of Kensington and the unincorporated census-designated place, North Bethesda. The Music Center at Strathmore, an arts and theater center, opened in February 2005 in the latter of these two areas and is presently the second home of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and the Fitzgerald Theatre in Rockville Civic Center Park has provided diverse entertainment since 1960. In 1998, Regal Cinemas opened in Town Center.[39]: 217 The city also has a brass band in the British style. The REM song "(Don't Go Back To) Rockville", released in 1984, was written by Mike Mills about not wanting his girlfriend to return to Rockville, Maryland.

Geography[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.57 square miles (35.15 km2), of which, 13.51 square miles (34.99 km2) is land and 0.06 square miles (0.16 km2) is water.[4]

Climate[edit]

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Rockville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[41] According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Rockville is in hardiness zone 7a,[42] meaning that the average annual minimum winter temperature is 0 to 5 °F (−18 to −15 °C).[43] The average first frost occurs on October 21, and the average final frost occurs on April 16.[44]

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 365 | — | |

| 1870 | 660 | 80.8% | |

| 1880 | 688 | 4.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,568 | 127.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,110 | −29.2% | |

| 1910 | 1,181 | 6.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,145 | −3.0% | |

| 1930 | 1,460 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 2,047 | 40.2% | |

| 1950 | 6,934 | 238.7% | |

| 1960 | 26,090 | 276.3% | |

| 1970 | 42,739 | 63.8% | |

| 1980 | 43,811 | 2.5% | |

| 1990 | 44,835 | 2.3% | |

| 2000 | 47,388 | 5.7% | |

| 2010 | 61,209 | 29.2% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 65,937 | [45] | 7.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[46] 2014 Estimate[6] | |||

Chinatown[edit]

In addition to North Potomac with a 27.59% Asian population and Potomac with close to 15%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Rockville is home to one of the largest Chinese communities in Maryland.[citation needed] According to the U.S. Census conducted in 2000, 14.5% of North Potomac's residents identified themselves as being of Chinese ancestry, making North Potomac the area with the highest percentage of Chinese ancestry in any place besides California and Hawaii.[citation needed] According to the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) enrollment demographic statistics, the two high schools in Montgomery County with the highest reported Asian ancestry are Thomas S. Wootton High School in Rockville, MD with a 32.1% Asian population and caters to the communities in North Potomac, Rockville, and Potomac, MD, and Winston Churchill High School in Potomac, MD with a 23.0% Asian population.[47][48][citation needed] Although North Potomac and Potomac have the highest concentration of Asian population in Maryland, the areas are largely residential and consist of suburban subdivisions. Thus, the more commercially favorable Rockville has become the center for Chinese/Taiwanese businesses since it is the county seat of Montgomery County and has large economic activity along Rockville Pike/Wisconsin Avenue (MD Route 355) in addition to having its own middle class and upscale residential areas. Rockville is widely considered to be a "Little Taipei" due to the area's high concentration of Taiwanese immigrants.[citation needed]

Although it is considered a satellite of the Washington D.C. Chinatown, Phuong Ly wrote in the Washington Post that the Montgomery County Chinatown is the "real Chinatown."[49] According to the article, Rockville's Chinatown spans along Rockville Pike from Halpine Road to East Jefferson Street, along E Jefferson Street and then along North Washington Street. Close to 30,000 people of Chinese descent live in Montgomery County, most of whom were drawn to the "good schools" and is home to at least three Chinese newspapers.[50] Cynthia Hacinli states that "fans of authentic Chinese food" come here instead of the downtown Chinatown on H Street.[51]

After the riots of 1968, many Chinese sought refuge in the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia, thus starting the decline of the H Street Chinatown. [52] According to another article, the largest concentrations of Chinese in the Washington DC area are in Montgomery County, Maryland at around 3%, while concentrations in Fairfax and Arlington Counties in Virginia are around 2 to 3%, which dwarfs that of Washington DC's Chinatown around 3%.[53] As the shift continues, the role that the urban Chinatown once played is now replaced by the "satellites" in the suburbs. It turns out that the "best food is no longer in Chinatown" and "... the closest Chinese grocery retailer is in Falls Church, Virginia."[54]

The Chinese New Year parade is held in the Rockville Town Square.[55]

Jewish Americans[edit]

Rockville is also the center of the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Area's Jewish population, containing several synagogues, kosher restaurants, and the largest of the Washington area's three Jewish community centers, part of a complex which includes a Jewish nursing home, day school, theater, and educational facility. There are also high percentages of Jewish population in the surrounding areas of North Potomac and Potomac, which are largely residential and not as commercially suitable as Rockville. The city also has large Korean and Indian populations.[citation needed]

The median income for a household in the city as of 2007 is $86,085. As of 2007, the median income for a family was $98,257. Males have a median income of $53,764 versus $38,788 for females. The per capita income for the city is $30,518. 7.8% of the population and 5.6% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 8.9% of those under the age of 18 and 7.9% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

2010 census[edit]

As of the census[5] of 2010, there were 61,209 people, 23,686 households, and 15,524 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,530.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,749.3/km2). There were 25,199 housing units at an average density of 1,865.2 per square mile (720.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.4% White (52.8% non-Hispanic white), 9.6% African American, 0.3% Native American, 20.6% Asian, 5.3% from other races, and 3.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.3% of the population.

There were 23,686 households of which 31.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.3% were married couples living together, 9.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.5% were non-families. 27.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.08.

The median age in the city was 38.7 years. 21.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 31.1% were from 25 to 44; 26.3% were from 45 to 64; and 14% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.9% male and 52.1% female.

Economy[edit]

Adventist HealthCare, the American Kidney Fund, Choice Hotels, Emergent BioSolutions, Human Genome Sciences, Westat, United States Pharmacopeia (USP), Bethesda Softworks and Goodwill Industries are headquartered in Rockville.

Largest employers[edit]

According to the city's 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[56] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Montgomery County | 4,985 |

| 2 | Montgomery County Public Schools | 2,500 |

| 3 | Lockheed Martin Information Systems | 2,000 |

| 4 | Westat | 2,000 |

| 5 | Booz Allen Hamilton | 1,282 |

| 6 | Montgomery College | 955 |

| 7 | Quest Software | 784 |

| 8 | BAE Systems | 650 |

| 9 | City of Rockville | 537 |

| 10 | Adventist HealthCare | 415 |

Sports[edit]

- Free State Roller Derby, a flat-track roller derby league based in Rockville.[57]

- Rockville Express, a Cal Ripken, Sr. Collegiate Baseball League team, 2007 CRSCBL League Champions

- Real Maryland Monarchs, a USL Premier Development League team.

Government[edit]

Rockville has a council-manager form of government.[58]

Mayor[edit]

The current Mayor of Rockville is Bridget Donnell Newton.

Rockville was incorporated in 1860, but its early records were destroyed by Confederate soldiers in July 1864.[59]

Rockville's mayors include:[3]

| Name | Tenure | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William V. Bouic[3] | 1888-1890[3] | Democrat | ||

| Daniel F. Owens[3] | 1890[3] | |||

| William V. Bouic[3] | 1890-1891[3] | |||

| Hattersley W. Talbott[3] | 1892-1893[3] | |||

| Jacob Poss[3] | 1893-1894[3] | |||

| John G. England[3] | 1894-1896[3] | |||

| Joseph Reading[3] | 1896-1898[3] | |||

| Spencer C. Jones[3] | 1898-1901[3] | |||

| Hattersley W. Talbott[3] | 1901-1906[3] | |||

| Lee Offutt[3] | 1906-1916[3] | |||

| Willis Burdette[3] | 1916-1918[3] | |||

| Lee Offutt[3] | 1918-1920[3] | |||

| O. M. Linthicum[3] | 1920-1924[3] | |||

| Charles G. Holland[3] | 1924-1926[3] | |||

| J. Roger Spates[3] | 1926-1932[3] | |||

| Douglas Blandford[3] | 1932-1946[3] | |||

| G. LaMar Kelly[3] | 1946-1952[3] | |||

| Daniel Weddle[3] | 1952-1954[3] | |||

| Dickran Y. Hovsepian[3] | 1954-1958[3] | |||

| Alexander J. Greene[3] | 1958-1962[3] | |||

| Frank A. Ecker[3] | 1962-1968[3] | |||

| Achilles M. Tuchtan[3] | 1968-1972[3] | |||

| Matthew J. McCartin[3] | 1972-1974[3] | |||

| William E. Hanna, Jr.[3] | 1974-1982[3] | |||

| John R. Freeland[3] | 1982-1984[3] | |||

| Viola D. Hovesepian[3] | 1984-1985[3] | Was appointed mayor.[3] | ||

| Steven Van Grack[3] | 1985-1987[3] | |||

| Douglas M. Duncan[3] | 1987-1993[3] | D-MD[3] | ||

| James Coyle[3] | 1993-1995[3] | |||

| Rose G. Krasnow[3] | 1995-2001[3] | |||

| Larry Giammo[3] | 2001-2007[3] | |||

| Susan R. Hoffmann[3] | 2007-2009[3] | |||

| Phyllis R. Marcuccio[3] | 2009-2013[3] | I-MD[3] | ||

| Bridget Donnell Newton[3] | 2013–present[3] | [3] | ||

Representative body[edit]

Rockville has a four-member City Council, whose members, along with the Mayor, serve as the governing body of the city. The Council members for the 2013 to 2015 session are Beryl L. Feinberg, Virginia Onley, Tom Moore, and Julie Palakovich Carr.

Departments and offices[edit]

The city manager oversees the following departments:

- Community Planning and Development Services

- Finance

- Human Resources

- Information and Technology

- Police

- Public Works

- Recreation and Parks[60]

Law enforcement[edit]

The city is serviced by the Rockville City Police Department and is aided by the Montgomery County Police Department as directed by authority.[61]

Education[edit]

Rockville is served by Montgomery County Public Schools. Public high schools in Rockville include Thomas S. Wootton High School, Richard Montgomery High School, and Rockville High School.

The Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School, the Melvin J. Berman Hebrew Academy and the Montrose Christian School, among other private schools, are located in Rockville.

Institutions of higher education in Rockville include Montgomery College (Rockville Campus), The University of Maryland University College (main campus is in Adelphi, Maryland), The Johns Hopkins University Montgomery County Campus (main campus is in Baltimore, Maryland), and the Universities at Shady Grove, a collaboration of nine Maryland public degree-granting institutions, all have Rockville addresses, but are outside the city limits.

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

The Red Line of the Washington Metro rail system services the Rockville station and the Twinbrook station. The Rockville station is located at Hungerford Drive near Park Road. The Twinbrook station is located near Rockville Pike and Halpine Road with entrances on Chapman Avenue.

At the same location as the Rockville metro station is Rockville Station on the Brunswick Line of the MARC commuter rail system, which runs to and from Washington, DC.

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides intercity train service to Rockville. The city's passenger rail station is located at 251 Hungerford Drive (at Park Road), ZIP code 20850; this is also the location of the MARC station described above.

- Amtrak Train 29, the westbound Capitol Limited, is scheduled to depart Rockville daily with service to Pittsburgh and overnight service to Chicago.

- Amtrak Train 30, the eastbound Capitol Limited, is scheduled to depart Rockville at 12:30pm on its return to Washington Union Station.

Sister cities[edit]

Rockville has one sister city:

It has a "friendship relationship" (a step preliminary to a sister-city relationship) with another city:

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Section 1. - City Incorporated; General Powers". Rockville City Code: General Ordinances of the City. Rockville, Maryland: The Mayor and Council of Rockville. February 26, 1990. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

The inhabitants of the City of Rockville, Montgomery County, are a body corporate by the name of 'The Mayor and Council of Rockville,' and by that name may have perpetual succession, sue and be sued, and have and use a common seal. (Res. No. 8-78; Res. No. 24-60)

- ^ "City of Rockville, Maryland". City of Rockville, Maryland. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv State of Maryland (February 25, 2013). "Rockville Mayors, Montgomery County, Maryland". Maryland Manual On-Line. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ^ a b "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Maryland's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting. Accessed 2011.04.12.

- ^ McGuckian, p. 2-3

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 3

- ^ a b c d McGuckian, p. 4

- ^ McGuckian, p. 6-9

- ^ McGuckian, p. 5

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 13

- ^ McGuckian, pp. 1-2

- ^ McGuckian, p. 14

- ^ McGuckian, p. 15

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 16

- ^ McGuckian, p. 17

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 18

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 22

- ^ McGuckian, p. 23

- ^ McGuckian, pp. 29-30

- ^ McGuckian, p. 31

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 26

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

McGuckian, p. 32was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ McGuckian, p. 41

- ^ McGuckian, p. 43

- ^ a b McGuckian, p. 46

- ^ McGuckian, p. 49

- ^ McGuckain, p. 50

- ^ "Capture of a Wagon Train: One Hundred and Seventy-eight Wagons and Over One Thousand Mules Gobbled Up: The Rebels in Possession of Rockville". Washington Evening Star. June 29, 1863. p. 2.

- ^ McGuckian, p. 52

- ^ McGuckian, pp. 53-54

- ^ McGuckian, pp. 54-55

- ^ Rockville Civil War Monument - Rockville, MD - American Civil War Monuments and Memorials on Waymarking.com

- ^ Confederate Soldier Monument Rockville, Maryland

- ^ "Congressional Airport Sold For Dwellings". The Washington Post. April 4, 1954. p. M6.

- ^ Goodman, S. Oliver (May 1, 1958). "New Rockville Shop Center Is Dedicated". The Washington Post. p. C14.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

McGuckianwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Transforming Rockville Town Center http://www.rockvillemd.gov/towncenter/

- ^ Climate Summary for Rockville, Maryland

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zones: Maryland & District of Columbia". Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ "Freeze / Frost Occurrence Data" (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ http://www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org/departments/regulatoryaccountability/glance/fy2004/schools/04234.pdf

- ^ "Winston Churchill High School - #602" (PDF).

- ^ Ly, Phuong (April 9, 2006). "MoCo's Chinatown". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ^ "MoCo's Chinatown" (PDF). The Washington Post.

- ^ Hacinli, Cynthia (18 February 2011). "Rockville: The New Chinatown?". Washingtonian magazine. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ^ Cambria, Jak. "Washington D.C. Chinatown USA". Chinatownology.com. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Asians are among the poorest".

- ^ Roberts, Steve (January–February 2013). "Meet the Sacrifice Generation". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ^ "2013 Chinese New Year in Washington, DC".

- ^ "City of Rockville CAFR". p. 104. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ The Black-Eyed Suzies, Free State's founding team, was founded in November 2009. FSRD welcomes women of all ages and skating levels to participate in this unique sport."

- ^ "FAQ - Council-Manager Form of Government". City of Rockville. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ "Rockville Mayors, Montgomery County, Maryland". Maryland State Archives. November 18, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ "Rockville City Government Organization". City of Rockville. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ "Rockville City Police".

- ^ "Rockville Sister City Corporation".

- ^ "Gazette - Rockville to welcome another Sister City: Jiaxing, China".

References[edit]

External links[edit]

Media related to Rockville, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rockville, Maryland at Wikimedia Commons Geographic data related to Wikipedian1234/sandbox at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Wikipedian1234/sandbox at OpenStreetMap- Official website

- The Washington Post's Guide to Rockville

- City of Rockville at the Wayback Machine (archived February 19, 1998)

- City of Rockville at the Wayback Machine (archived November 14, 1996)

Category:Populated places established in 1717

Category:Cities in Montgomery County, Maryland

Category:County seats in Maryland

Category:1717 establishments in Maryland

Category:Cities in Maryland