User:Vivexdino/sandbox

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

The history of Japan includes the history of the islands of Japan and the Japanese people, spanning the ancient history of the region to the modern history of Japan as a nation state. Following the last ice age, around 12,000 BC, the rich ecosystem of the Japanese archipelago fostered human development. The earliest-known pottery found in Japan belongs to the Jōmon period. The first known written reference to Japan is in the brief information given in Book of Han in the 1st century AD. The main cultural and religious influences came from China.[1]

The current Imperial House emerged in the sixth century and the first permanent imperial capital was founded in 710 at Heijō-kyō (modern Nara), which became a center of Buddhist art, religion and culture. The development of a strong centralized government culminated in the establishment of a new imperial capital at Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto) and the Heian period is considered a golden age of classical Japanese culture. Over the following centuries the power of the reigning emperor and the court nobility gradually declined and the once centralized state became increasingly fractured. By the time of the fifteenth century political power was subdivided into several hundred local units, or so called "domains" controlled by local daimyō, each with his own force of samurai warriors. After a long period of civil war, Tokugawa Ieyasu completed the unification of Japan and was appointed shogun by the emperor in 1603. He distributed the conquered land among his supporters, and set up his "bakufu" (literally "tent office" i.e. military rule) at Edo (modern Tokyo) while the nominal sovereign, the emperor, continued to reside in the old capital of Kyoto. The Edo period was prosperous and peaceful. Japan terminated the Christian missions and cut off almost all contact with the outside world.

In the 1860s the shogunate came to an end, power was returned to the emperor and the Meiji period began. The new national leadership systematically ended feudalism and transformed an isolated, underdeveloped island country, into a world power that closely followed Western models. Democracy was problematic, because Japan's powerful military was semi-independent and overruled—or assassinated—civilians in the 1920s and 1930s. The military invaded Manchuria in 1931 and escalated the conflict to all-out war on China in 1937. Japan controlled the coast and major cities and set up puppet regimes, but was unable to entirely defeat China. Its attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 led to war with the United States and its allies. After a series of naval victories by mid-1942, Japan's military forces were overextended and its industrial base was unable to provide the needed ships, armaments, and oil. But even with the navy sunk and the main cities destroyed by U.S. air attacks, the military held out until August 1945 when the twin shock of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria made it possible for the emperor to force the military to surrender.

The U.S. occupied Japan until 1952. Under the supervision of the U.S. occupation forces a new constitution was drafted and enacted in 1947 that transformed Japan into a parliamentary monarchy. After 1955, Japan enjoyed very high economic growth rates, and became a world economic powerhouse, especially in engineering, automobiles and electronics with a highly developed infrastructure, a very high standard of living and the highest life expectancy in the world. Emperor Shōwa died in 1989 and his son Emperor Akihito ascended the throne marking the beginning of a new era. Since the 1990s economic stagnation has been a major issue, with an earthquake and tsunami in 2011 causing massive economic dislocations and loss of nuclear power.

Japanese prehistory[edit]

Paleolithic Age[edit]

The Japanese Paleolithic age covers a lengthy period starting as early as 50,000 BC, and ending sometime around 12,000 BC, at the end of the last ice age. Artifacts claimed to be older than ca. 38,000 BC are not generally accepted, and most historians therefore believe that the Japanese Paleolithic started 40,000 years ago.[2]

The Japanese archipelago would become disconnected from the mainland continent after the last ice age, around 11,000 BC. After a hoax by an amateur researcher, Shinichi Fujimura, had been exposed,[3] the Lower and Middle Paleolithic evidence reported by Fujimura and his associates has been rejected after thorough reinvestigation.

As a result of the fallout over the hoax, now only some Upper Paleolithic evidence (not associated with Fujimura) can be considered as having been well established.

Jōmon period[edit]

The Jōmon period lasted from about 14,000 until 300 BC. The first signs of stable living patterns appeared around 14,000 BC with the Jōmon culture, characterized by a Mesolithic to Neolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer lifestyle of wood stilt house and pit dwellings and a rudimentary form of agriculture.

Weaving was still unknown at the time and clothes were often made of furs. The Jōmon people started to make clay vessels, decorated with patterns made by impressing the wet clay with braided or unbraided cord and sticks. Based on radio-carbon dating, some of the surviving examples of pottery can be found in Japan along with daggers, jade, combs made of shells, and various other household items dated to the 11th century BC.[4]

The most recent finds, in 1998, have been at the Odai Yamamoto I site, where fragments of a single vessel are dated to 14,500 BC (ca 16,500 BP); this places them as, or amongst, the earliest pottery currently known in Japan.[5][6][7] Among older discoveries, calibrated radiocarbon measures of carbonized material from pottery artifacts: Fukui Cave 12500 ± 350 BP and 12500 ± 500 BP, Kamikuroiwa rock shelter 12, 165 ± 350 years BP in Shikoku.[8] although the specific dating is disputed.

Elaborate pottery figurines known as dogū are found from the Late Jōmon period.

Yayoi period[edit]

The Yayoi period lasted from about 400 or 300 BC until 250 AD, following the Jōmon period, and is named after Yayoi, a subsection of Bunkyō, Tōkyō, where archaeological investigations uncovered its first recognized traces.

The start of the Yayoi period marked the influx of new practices such as weaving, rice farming, and iron and bronze making. Bronze and iron appear to have been simultaneously introduced into Yayoi Japan. Iron was mainly used for agricultural and other tools, whereas bronze was used for ritual and ceremonial artifacts. Some casting of bronze and iron began in Japan by about 100 BC, but the raw materials for both metals were introduced from the Asian continent. The Yayoi period brought Shamanism and divination by oracles to Shintō, in order to guarantee good crops.[9]

Japan first appeared in written records in 57 AD with the following mention in China's Book of the Later Han:[10] "Across the ocean from Lelang are the people of Wa. Formed from more than one hundred tribes, they come and pay tribute frequently." The book also recorded that Suishō, the king of Wa, presented slaves to the Emperor An of Han in 107. The Sānguó Zhì (Records of the Three Kingdoms), written in the 3rd century, noted that the country was the unification of some 30 small tribes or states and ruled by a shaman queen named Himiko of Yamataikoku.

During the Han and Wei dynasties, Chinese travelers to Kyūshū recorded its inhabitants who claimed that they were the descendants of the Grand Count (Tàibó) of the Wu. The inhabitants also show traits of the pre-sinicized Wu people with tattooing, teeth-pulling, and baby-carrying. The Sānguó Zhì records the physical descriptions which are similar to ones on haniwa statues, such as men wearing braided hair and tattoos and women wearing large, single-pieced clothing.

The Yoshinogari site in Kyūshū is the most famous archaeological site of the Yayoi period and reveals a large settlement continuously inhabited for several hundred years. Archaeological excavation has shown the most ancient parts to be from around 400 BC. It appears that the inhabitants had frequent communication and trade relations with the mainland. Today, some reconstructed buildings stand in the park on the archaeological site.[11]

Ancient Japan[edit]

Kofun period[edit]

The Kofun period began around 250 AD, and is named after the large tumulus burial mounds called kofun (古墳, from Sino-Japanese "ancient grave") that started appearing around that time.

The Kofun period (the "Kofun-jidai") saw the establishment of strong military states, each of them concentrated around powerful clans (or zoku). The establishment of the dominant Yamato polity was centered in the provinces of Yamato and Kawachi from the 3rd century AD until the 7th century, establishing the origin of the Japanese imperial lineage. And so the polity, by suppressing the clans and acquiring agricultural lands, maintained a strong influence in the western part of Japan.[citation needed]

Japan started to send tributes to Imperial China in the 5th century. In the Chinese history records, the polity was called Wa, and its five kings were recorded. Based upon the Chinese model, they developed a central administration and an imperial court system, with its society being organized into various occupation groups. Close relationships between the Three Kingdoms of Korea and Japan began during the middle of this period, around the end of the 4th century.[citation needed]

Classical Japan[edit]

Asuka period[edit]

During the Asuka period (538 to 710), the proto-Japanese Yamato polity gradually became a clearly centralized state, defining and applying a code of governing laws, such as the Taika Reforms and Taihō Code.[12] After the latter part of the fourth century, the three kingdoms of Korea refused cooperation and were often in conflict with one another. During the reign of Emperor Kotoku, envoys often visited from Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla.

Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 538 by the King Seong of Baekje, to whom Japan continued to provide military support.[13][14][15] Buddhism was promoted largely by the ruling class for their own purposes. Accordingly, in the early stages, Buddhism was not a popular religion with the common people of Japan.[16] The practice of Buddhism, however, led to the discontinuance of burying the deceased in large kofuns.

Prince Shōtoku came to power in Japan as Regent to Empress Suiko in 594. Empress Suiko had come to the throne as the niece of the previous Emperor, Sujun (588–593), who had been assassinated in 593. Empress Suiko had also been married to a prior Emperor, Bidatsu (572–585), but she was the first female ruler of Japan since the legendary matriarchal times.[17]

As Regent to Empress Suiko, Prince Shotoku devoted his efforts to the spread of Buddhism and Chinese culture in Japan.[17] He also brought relative peace to Japan through the proclamation of the Seventeen-article constitution, a Confucian style document that focused on the kinds of morals and virtues that were to be expected of government officials and the emperor's subjects. Buddhism would become a permanent part of Japanese culture.

A letter brought to the Emperor of China by an emissary from Japan in 607 stated that the "Emperor of the Land where the Sun rises (Japan) sends a letter to the Emperor of the land where Sun sets (China)",[18] thereby implying an equal footing with China which angered the Chinese emperor.[19]

Nara period[edit]

The Nara period of the 8th century marked the emergence of a strong Japanese state and is often portrayed as a golden age. In 710, the capital city of Japan was moved from Asuka to Nara.[20] Hall (1966) concludes that "Japan had been transformed from a loose federation of uji in the fifth century to an empire on the order of Imperial China in the eighth century. A new theory of state and a new structure of government supported the Japanese sovereign in the style and with the powers of an absolute monarch."[21] Traditional, political, and economic practices were now organized through a rationally structured government apparatus that legally defined functions and precedents. Lands were surveyed and registered with the state. A powerful new aristocracy emerged. This aristocracy controlled the state and was supported by taxes that were efficiently collected. The government built great public works, including government offices, temples, roads, and irrigation systems. A new system of land tenure and taxation, which was designed to widely spread land ownership throughout the rural population, was introduced. Such allotments tended to be about one acre. However, they could be as small as one-tenth of an acre. However, lots for slaves were about two-thirds the size of the allotments to free men. Allotments were reviewed every five years when the census was conducted.[22]

There was a cultural flowering during this period.[20] Soon, dramatic new cultural manifestations characterized the Nara period, which lasted four centuries.[23]

Following an imperial rescript by Empress Gemmei, the capital was moved to Heijō-kyō, present-day Nara, in 710. The city was modeled on Chang'an (now Xi'an), the capital of the Chinese Tang Dynasty.

During the Nara Period, political development was marked by a struggle between the imperial family and the Buddhist clergy,[22] as well as between the imperial family and the regents—the Fujiwara clan. Japan did enjoy peaceful relations with their traditional foes—the Balhae people—who occupied the south of Manchuria. Japan also established formal relationships with the Tang dynasty of China.[24]

In 784, the capital was again moved to Nagaoka-kyō to escape the Buddhist priests; in 794, it was moved to Heian-kyō, present-day Kyōto. The capital was to remain in Kyōto until 1868.[25] In the religious town of Kyōto, Buddhism and Shintō began to form a syncretic system.[26]

Historical writing in Japan culminated in the early 8th century with the massive chronicles, the Kojiki (The Record of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720). These chronicles give a legendary account of Japan's beginnings, today known as the Japanese mythology. According to the myths contained in these chronicles, Japan was founded in 660 BC by its legendary first Emperor Jimmu, a direct descendant of the Shintō sun goddess, Amaterasu. The myths recorded that Jimmu started a line of emperors that remains to this day. Historians assume that the myths partly describe historical facts, but the first emperor who actually existed was Emperor Ōjin, though the date of his reign is uncertain. Since the Nara period, actual political power has not been in the hands of the emperor but has, instead, been exercised at different times by the court nobility, warlords, the military, and, more recently, the Prime Minister of Japan. The Man'yōshū, a collection of 4500 poems, was also compiled at the end of this period in 759.

Heian period[edit]

The Heian period, lasting from 794 to 1185, is the final period of classical Japanese history. It is considered the peak of the Japanese imperial court and noted for its art, especially its poetry and literature. In the early 11th century, Lady Shikibu Murasaki wrote what is called Japan's (and sometimes the world's) oldest surviving novel, The Tale of Genji.[27] Kokin Wakashū,[28] one of the oldest existing collections of Japanese poetry, was compiled during this period.

Strong differences from mainland Asian cultures emerged (such as an indigenous writing system, the kana). Due to the decline of the Tang Dynasty,[29] Chinese influence in Japan (at the time) had reached its peak, and then effectively ended, with the last imperially sanctioned mission to Tang China in 838, although trade expeditions and Buddhist pilgrimages to China continued.[30]

Political power in the imperial court was in the hands of powerful aristocratic families (kuge), especially the Fujiwara clan, who ruled under the titles Sesshō and Kampaku (imperial regents). The Fujiwara clan obtained almost complete control over the imperial family. However, the Fujiwara Regents who advised the Imperial Court were content to derive their authority from imperial line. This meant that the Fujiwara authority could always be challenged by a vigorous emperor. Fujiwara domination of the Court during the time from 858 until about 1160 led to this period being called "the Fujiwara Period."[31] The Fujiwara clan gained this ascendancy because of their matrimonial links with the imperial family.[32] Indeed, because of the number of emperors that were born to Fujiwara mothers, the Fujiwara Regents became so closely identified with the imperial family, that people saw no difference between the "direct rule" by the imperial family and the rule of the Fujiwara Regents.[33] Accordingly, when dissatisfaction with the government arose resulting in the Hōgen Rebellion (1156–1158), the Heiji Rebellion (1160) and the Gempei War (1180–1185), the target of the dissatisfaction was the Fujiwara Regents, as well as the Imperial family. The Gempei War ended in 1185 with the naval battle of Dan-no-ura in which the Minamoto clan defeated the Taira clan. In 1192, the Court appointed Yoritomo of the Minamoto clan to a number of high positions in government. These positions were consolidated and Yoritomo became the first person to be designated the Seii-tai-shōgun or "Shōgun."[34] Yoritomo then defeated the Fujiwara clan in a military campaign in the north of Japan. This spelled the end of the Fujiwara Period and the end of Fujiwara influence over the government.

The end of the period saw the rise of various military clans. The four most powerful clans were the Minamoto clan, the Taira clan, the Fujiwara clan, and the Tachibana clan. Towards the end of the 12th century, conflicts between these clans turned into civil war, such as the Hōgen (1156–1158). The Hōgen Rebellion was of cardinal importance to Japan, since it was the turning point that led to the first stages of the development of feudalism in Japan.[35] The Heiji Rebellion of 1160 also occurred during this period[36] and the uprising was followed by the Genpei War, from which emerged a society led by samurai clans under the political rule of the shōgun—the beginnings of feudalism in Japan.

Buddhism began to spread during the Heian Period. However, Buddhism was split between two sects—the Tendai sect which had been brought to Japan from China by Saichō (767–822) and the Shingon sect which had been introduced from China by Kūkai (774–835). Whereas the Tendai sect tended to be a monastic form of Buddhism which established isolated monasteries or temples on the tops of mountains,[37] the Shingon variation of Buddhism was a less philosophical and more practical and more popular version of the religion.[38] Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo-shū, Jōdo Shinshū) was a form of Buddhism which was much simpler than either the Tendai or Shingon versions of Buddhism. Pure Land Buddhism became very popular in Japan during a time of degeneration and trouble in the latter half of the 11th century.[39]

Medieval Japan (1185–1573/1600)[edit]

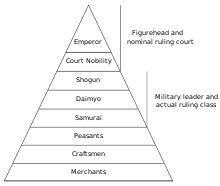

The medieval or "feudal" period of Japanese history, dominated by the powerful regional families (daimyō) and the military rule of warlords (shōgun), stretched from 1185 to 1573/1600. The emperor remained but was mostly kept to a de jure figurehead ruling position, and the power of merchants was weak. This time is usually divided into periods following the reigning family of the shōgun.

Kamakura period[edit]

The Kamakura period, 1185 to 1333, is a period that marks the governance of the Kamakura shogunate and the transition to the Japanese "medieval" era, a nearly 700-year period in which the emperor, the court, and the traditional central government were left intact but largely relegated to ceremonial functions. Civil, military, and judicial matters were controlled by the bushi (samurai) class, the most powerful of whom was the de facto national ruler, the shōgun. This period in Japan differed from the old shōen system in its pervasive military emphasis.

In 1185, Minamoto no Yoritomo and his younger brother, Yoshitsune defeated the rival Taira clan at the naval battle of Dan-no-ura.[40] The outcome of the Battle of Dan-no-ura meant the rise of the warrior or samurai class. Under the feudal structure that was arising in Japan, the samurai owed military service and loyalty to the emperor; the samurai in turn required loyalty and work from the peasants who rented land from them and served them. On occasion the samurai would conduct warfare against each other, which caused disruption to the society. In 1192, Yoritomo was appointed Seii Tai-Shōgun by the emperor.[34] The shōgun was expected to run the day-to-day affairs of the government on behalf of the emperor and to keep the samurai in line. During this time the Imperial Court remained in their capital of Kyōto. Society at Kyōto was regarded as more refined and cultured than the rest of the country.[41] However, Yoritomo established his base of power called the Bakufu in the seaside town of Kamakura.[34] Yoritomo became the first in a line of shōguns who ruled from Kamakura. Thus, the period of time from 1185 until 1333 became known as the period of the Kamakura Shogunate. Society in the military or samurai capital of Kamakura was regarded as rough and ignorant by comparison with the refined society at Kyōto.[41] However, Yoritomo wished to free his government from the pernicious influence of the bureaucracy in Kyōto and thus remained in Kamakura. The Kamakura Shogunate-based itself on the interests of this rising class rather than on the bureaucracy at Kyōto. Accordingly, the preference of Kamakura as the capital of the shogunate fit this new warrior class.

Yoritomo was married to Hōjō Masako of the Hōjō clan, herself a sensei (teacher) in kyūjutsu (the art of the bow) and kenjutsu (the art of the sword), and she contributed much to his ascent and the organization of the Bafuku. After Yoritomo's death, another warrior clan, the Hōjō, came to rule as shikken (regents) for the shōgun.

Two traumatic events of the period were the Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and in 1281. Massive Mongol forces with superior naval technology and weaponry attempted a full-scale invasion of the Japanese islands in both 1274 and in 1281. However, a famous typhoon referred to as kamikaze (translating as divine wind in Japanese) is credited with devastating both Mongol invasion forces and saving Japan.[42] Although the Japanese were successful in stopping the Mongols, the invasion attempt had devastating domestic repercussions, leading to the extinction of the Kamakura shogunate. For two decades after the second failed Mongol invasion of Japan, the Japanese remained fearful of a third Mongol attempt. (Indeed, Japan could not rest assured of peace until the death of Kublai Khan in 1294.) Consequently, the shōgun required the various samurai to spend money lavishly on armed forces in order to remain in a high state of readiness for the expected third attack by the Mongols. This vast expenditure of money had a ruinous effect on the economy of Japan. The Kamakura Shogunate could perhaps have survived the strain of the continual military readiness and the resultant bad economy if that had been the only problem. However, upon the death of Emperor Go-Saga in 1272, there arose a bitter dispute over succession to the throne within the imperial family.

Kemmu Restoration[edit]

In 1333, the Kamakura shogunate was overthrown in a coup d'état known as the Kemmu Restoration, led by Emperor Go-Daigo and his followers (Ashikaga Takauji, Nitta Yoshisada, and Kusunoki Masashige). Emperor Go-Daigo had come to the throne in 1318. From the beginning, Go-Daigo had made it clear that he was not going to abdicate and become a "cloistered emperor" and that he was intending to rule Japan from his palace in Kyōto, independent of the Kamakura Shogunate.[43] Go-Daigo and his supporters went to war against the Kamakura Shogunate, the Imperial House was restored to political influence, and the government was now a civilian one, replacing the military government of the Kamakura Shogunate. However, this did not last. The warrior class throughout Japan was in tumult.[44] Furthermore, Go-Daigo was not a gifted leader, tending, instead, to alienate people.[44] One of those that was alienated by Go-Daigo, was his former supporter, Ashikaga Takauji. Ashikaga Takauji found that he had support from other regional warlords in Japan. In early 1335, Ashikaga left Kyōto and moved to Kamakura.[45] Ashikaga, then began assuming powers that had not been given him by the Emperor. This brought Ashikaga Takauji in direct conflict with the governmental officials in Kyōto, including his old allies, Nitta Yoshisada and Kusunoki Masashige. However, by assuming shōgun-like powers, Ashikaga appeared to be standing up for the warrior class against the civilian authority that seemed intent on destroying the power of the warriors. Accordingly, Ashikaga Takauji was joined in Kamakura by a number of other regional warlords. On November 17, 1335, Ashikaga Tadayoshi, brother of Takauji, issued a call (in the name of his brother Takauji) asking the warriors throughout the country to "assemble your clansmen and hasten to join me."[46] Dissatisfaction with Go-Daigo was so strong that a majority of the warriors in Japan answered this call.[47]

After initial defeats on the main island of Honshū, Ashikaga and his troops retreated to the southern island of Kyūshū, where he immediately won over most of the regional warlords to his side and defeated the few who remained loyal to Go-Daigo. With all the island of Kyūshū in his hands, Ashikaga Takauji invaded the main island of Honshū again and, in 1336, at the decisive Battle of Minatogawa, or the Battle of Minato River, defeated the armed forces of Nitta Yoshisada and Kusunoki Masanori and the other loyalist forces of Go-Daigo. The victorious warrior-class forces gathered around the town of Kamakura which became known as the "Northern Court." The Loyalist forces may have been defeated but they survived to fight on. They formed the "Southern Court" and upon the death of Go-Daigo in the late summer of 1339, they rallied around the person of Prince Kazuhito who was enthroned as Emperor Kōgon. Prince Kazuhito was from a younger line of descendents in the Imperial family and, thus, his supporters were supporters of the "junior line." On September 20, 1336, the Ashikaga coalition of samurai opposed to Go-Daigo enthroned Prince Yutahito as Emperor Kōmyō.[48] Prince Yutahito was from the "senior line" of descendents in the Imperial family. Accordingly, the civil war between the warriors led by the Ashikaga clan—the Northern Court on the one hand and the "Loyalist" Southern Court on the other hand, became a civil war of imperial succession between followers of the "senior" and "junior" lines of succession in the Imperial family. The warriors and the Ashikaga clan captured Kyōto and proceeded to move their forces from Kamakura to Kyōto. Meanwhile, the Southern Court, deposed from their capital in Kyōto, now established themselves in Yoshino.

The Ashikaga Shogunate was never able to control and centralize the government over the entire country. Rather they ruled because of a narrow and shifting majority of warlords who supported them. There were always some warlords that acted independently of either the Northern Court or the Southern Court. Later, during the war of succession, these independent warlords enthroned a third emperor—Emperor Suko. So the civil war of succession became a three-cornered affair. The prestige of the throne declined as the civil war continued. This had the effect of bolstering the idea that the Imperial family should be removed from politics and strengthened the need for a shōgun to be appointed to run the government on a day-to-day basis.

In 1338, Ashikaga Takauji was officially appointed as Shōgun by the new Emperor. He was the first of a line of Ashikaga shōgun. The attempted restoration of independent power of the throne—the Kemmu Restoration—was at an end and the period of the Ashikaga Shogunate had begun.

The civil war of succession to the throne was finally settled. As part of the settlement, all three "emperors" abdicated on April 6, 1352.[49] Ashikaga died in 1358 and Ashikaga Yoshiakira succeeded him as Shōgun.[50] By 1368, however, the ascendancy of the Ashikaga Shogunate was so complete that Ashikaga Yoshimitsu was able to rule Japan without reference to the emperor.[51] In 1392, the Southern Court and the Northern Court were finally merged under an agreement that pledged that the throne would, henceforth, alternate between candidates of the Northern Court and the Southern Court. This agreement was, however, never implemented.

Muromachi period[edit]

During the Muromachi period, the Ashikaga shogunate ruled for 237 years from 1336 to 1573. It was established by Ashikaga Takauji who seized political power from Emperor Go-Daigo. A majority of the warrior class supported the Ashikaga clan in the succession war. After taking Kyōto from Emperor Go-Daigo, the Ashikaga clan made Kyōto the capital of the Ashikaga Shogunate in late 1336.[52] This became the new capital of the Northern Court. Go-Daigo, then, moved to the town of Yoshino and established the new capital of the Southern Court there. This ended the attempted restoration of the powers of the throne—the Kemmu restoration. The early years (1336 to 1392) of the Muromachi period are known as the Nanboku-chō (Northern and Southern court) period because the imperial court was split in two. In 1392, the Northern court and the southern Court were finally merged and Emperor Kogon was placed on the throne. There was an agreement that, heretofore, succession to the throne would alternate between candidates of the Northern court and candidates of the Southern Court. However, this agreement was never acted upon.

Rule of the Ashikaga Bakufu looked a lot like the rule of the Kamakura Bakufu, as the Ashikaga clan made few changes in the offices and councils of the prior government.[53] However, the Ashikaga Shogunate dominated the Imperial throne more than the Kamakura Shogunate ever did. Nonetheless, the Ashikaga Shogunate was never able to centralize its power over the regional warlords as much as the prior Kamakura government. The Ashikaga Shogunate was based on a coalition of a loose majority of the various regional warlords across the country. As a consequence, the Ashikaga Shogunate was unable to do anything about the problem of the pirates who were operating off their own shores, despite repeated requests to do so by both Korea[54] and Ming dynasty China.[55] Warlord clans, like the Kotsuna clan and the Kiyomori branch of the Taira clan, that lived along the coast of the Inland Sea, made money from the pirates and supported them.[56]

In 1368, the Ming Dynasty replaced the Yuan Dynasty of the Mongols in China. Japanese trade with China had been frozen since the second and final attempt by Mongol China to invade Japan in 1281. Now a new trade relationship began with the new Ming rulers in China. Part of the new trade with China was the coming to Japan of Zen Buddhist monks. During the Ashikaga Shogunate Zen Buddhism came to have a great influence with the ruling class in Japan.[57]

The Muromachi period ended in 1573 when the 15th and last shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, was driven out of the capital in Kyōto by Oda Nobunaga.

In the viewpoint of a cultural history, Kitayama period (end of 14th – first half of 15th century[58]) and Higashiyama period (second half of 15th – first half of 16th century[58]) exist in Muromachi period.

Sengoku period[edit]

The later years of the Muromachi period, 1467 to 1573, are also known as the Sengoku period (Period of Warring Kingdoms), a time of intense internal warfare, and correspond with the period of the first contacts with the West—the arrival of Portuguese "Nanban" traders.

In 1543, a Portuguese ship, blown off its course to China, landed on Tanegashima Island. Firearms introduced by the Portuguese would bring the major innovation of the Sengoku period, culminating in the Battle of Nagashino where reportedly 3,000 arquebuses (the actual number is believed to be around 2,000) cut down charging ranks of samurai. During the following years, traders from Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and Spain arrived, as did Jesuit, Dominican, and Franciscan missionaries.

Azuchi-Momoyama period[edit]

The Azuchi-Momoyama period runs from approximately 1569 to 1603. The period, regarded as the late Warring Kingdoms period, marks the military reunification and stabilization of the country under a single political ruler, first by the campaigns of Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) who almost united Japan. Nobunaga decided to reduce the power of the Buddhist priests, and gave protection to Christianity. He slaughtered many Buddhist priests and captured their fortified temples. He was killed in a revolt in 1582.[59] Unification was finally achieved by one of Nobunaga's generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

After having united Japan, Hideyoshi launched the conquest of China's Ming Dynasty by way of Korea. However, after two unsuccessful campaigns towards the allied forces of Korea and China and his death, his forces returned to Japan in 1598 (the Bunroku-Keichō War). Following his death, Japan experienced a short period of succession conflict. Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the regents for Hideyoshi's young heir, emerged victorious at the Battle of Sekigahara and seized political power.

Christian missions[edit]

Roman Catholic Jesuit missionaries led by Francis Xavier (1506–1552) arrived in 1549 and were welcomed in Kyōto.[60] Their proselytizing was most successful in Kyūshū, with about 100,000 to 200,000 converts, including many daimyō.[61] In 1587, Hideyoshi reversed course and decided the Christian presence was divisive and might present the Europeans with an opportunity to disrupt Japan. The Christian missionaries were seen as a threat; the Portuguese merchants were allowed to continue their operations. The edict was not immediately enforced but restrictions grew tighter in the next three decades until a full-scale government persecution destroyed the Christian community by the 1620s. The Jesuits were expelled, churches and schools were torn down, and the daimyō were forbidden to become Christians. Converts who did not reject Christianity were killed. Many Christians went underground, becoming hidden Christians (隠れキリシタン, kakure kirishitan), but their communities died out. Not until the 1870s was Christianity re-established in Japan.[62][63]

Edo period (1603–1868)[edit]

The Edo, or Tokugawa period saw power centralized in the hands of a hereditary shogunate that took control of religion, regulated the entire economy, subordinated the nobility, and set up uniform systems of taxation, government spending and bureaucracies. It avoided international involvement and wars, established a national judiciary and suppressed protest and criticism. The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million.

Economy[edit]

About 80% of the people were rice farmers.[64] Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable, so prosperity increased. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.[65] Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of irrigation to their paddies. The daimyō operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade. Large-scale rice markets developed, centered on Edo and Ōsaka.[66] In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services. The merchants, while low in status, prospered, especially those with official patronage. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, currency came into common use, and the strengthening credit market encouraged entrepreneurship.[67]

The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much. One scholar observed that the entire military class was living "as in an inn, that is, consuming now and paying later".[68] The bakufu and daimyō raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt. By 1750 rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threatened the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—with prohibitions on spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshimune (in office 1716–1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shōgun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829). Other shōgun debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation.[69]

By 1800 the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Some wealthy merchants sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class.

A few domains, notably Chōshū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tenpō Reforms" (1830–1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.[70]

Social structure[edit]

Japanese society had an elaborate social structure, in which everyone knew their place and level of prestige. At the top were the Emperor and the court nobility, invincible in prestige but weak in power. Next came the shōgun, daimyō and layers of feudal lords whose rank was indicated by their closeness to the Tokugawa. They had power. The "daimyō" comprised about 250 local lords of local "han" with annual outputs of 50,000 or more bushels of rice. The upper strata was much given to elaborate and expensive rituals, including elegant architecture, landscaped gardens, Noh drama, patronage of the arts, and the tea ceremony.[71]

Samurai[edit]

Next in the social structure were the 400,000 warriors, called "samurai", whose ranks ranged in numerous grades and degrees. A few upper samurai were eligible for high office; most were foot soldiers (ashigaru) with minor duties. The samurai were affiliated with senior lords in a well-established chain of command. The shōgun had 17,000 samurai retainers; the daimyō each had hundreds. Most lived in modest homes near their lord's headquarters, and lived off hereditary rights to collect rents and stipends. Together these high status groups comprised Japan's ruling class making up about 6% of the total population.[72]

Lower orders[edit]

The lower social orders were divided into two main segments—the peasants—85% of the population—whose high prestige as producers was undercut by their burden as the chief source of taxes. They were illiterate and lived in villages controlled by appointed officials who kept the peace and collected taxes. Peasants and villagers frequently engaged in unlawful and disruptive protests, especially after 1780.[73]

Merchants and artisans[edit]

Near the bottom of the prestige scale—but much higher up in terms of income and life style—were the merchants and artisans of the towns and cities. They had no political power, and even rich merchants found it difficult to rise in the world in a society in which place and standing were fixed at birth.[74] Finally came the entertainers, prostitutes, day laborers and servants, and the thieves, beggars and hereditary outcasts. They were tightly controlled by local officials and were not allowed to mingle with higher status people.[75]

Literacy[edit]

Literacy was highly prized, albeit made difficult by the writing system. Wood block printing had been standard for centuries; after 1500 Japanese printers experimented with movable type, but reverted to the wood blocks. By the 1780s Japan was publishing 3000 books a year (compared with 400 in Russia). By the 1850s the major new trend was the translation of western scientific and geographical books, which reached a wide audience. By 1860 about 40% of the men and 10% of the women were literate in rural areas, with much higher rates in the cities, such as 80% in Edo (Tōkyō).[76] Universal compulsory education only began in 1871.[77]

Government[edit]

During the Edo period, also called the Tokugawa period, the administration of the country was shared by over two hundred daimyō in a federation governed by the Tokugawa shogunate. The Tokugawa clan, leader of the victorious eastern army in the Battle of Sekigahara, was the most powerful of them and for fifteen generations monopolized the title of Sei-i Taishōgun (often shortened to shōgun). With their headquarters at Edo (present-day Tōkyō), the Tokugawa commanded the allegiance of the other daimyō, who in turn ruled their domains with a rather high degree of autonomy.

The Tokugawa shogunate carried out a number of significant policies. They placed the samurai class above the commoners: the farmers, artisans, and merchants. They enacted sumptuary laws limiting hairstyle, dress, and accessories. They organized commoners into groups of five and held all responsible for the acts of each individual. To prevent daimyō from rebelling, the shōguns required them to maintain lavish residences in Edo and live at these residences on a rotating schedule; carry out expensive processions to and from their domains; contribute to the upkeep of shrines, temples, and roads; and seek permission before repairing their castles.

This 265-year span was called "A peaceful state". Cultural achievement was high during this period, and many artistic developments took place. Most significant among them were the ukiyo-e form of wood-block print and the kabuki and bunraku theaters. Also, many of the most famous works for the koto and shakuhachi date from this time period.

Sakoku—seclusion from the outside world[edit]

This article appears to contradict the article Sakoku. (January 2023) |

During the early part of the 17th century, the shogunate suspected that foreign traders and missionaries were actually forerunners of a military conquest by European powers. Christianity had spread in Japan, especially among peasants, and the shogunate suspected the loyalty of Christian peasants towards their daimyō, severely persecuting them. This led to a revolt by persecuted peasants and Christians in 1637 known as the Shimabara Rebellion which saw 30,000 Christians, rōnin, and peasants facing a massive samurai army of more than 100,000 sent from Edo. The rebellion was crushed at a high cost to the shōgun's army.

After the eradication of the rebels at Shimabara, the shogunate placed foreigners under progressively tighter restrictions. It monopolized foreign policy and expelled traders, missionaries, and foreigners with the exception of the Dutch and Chinese merchants who were restricted to the man-made island of Dejima in Nagasaki Bay and several small trading outposts outside the country. However, during this period of isolation (Sakoku) that began in 1635, Japan was much less cut off from the rest of the world than is commonly assumed, and some acquisition of western knowledge occurred under the Rangaku system. Russian encroachments from the north led the shogunate to extend direct rule to Hokkaidō, Sakhalin and the Kuriles in 1807, but the policy of exclusion continued.

End of seclusion[edit]

The policy of isolation lasted for more than 200 years. In 1844, William II of the Netherlands sent a message, urging Japan to open its doors. This was rejected by the Japanese.[78] On July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy with four warships—the Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna—steamed into the bay in Yokohama and displayed the threatening power of his ships' cannons during a Christian burial which the Japanese observed. He requested that Japan open to trade with the West. These ships became known as the kurofune, the Black Ships.

The following year at the Convention of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854, Perry returned with seven ships and demanded that the shōgun sign the Treaty of Peace and Amity, establishing formal diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States. Within five years, Japan had signed similar treaties with other Western countries. The Harris Treaty was signed with the United States on July 29, 1858. These treaties were unequal, having been forced on Japan through gunboat diplomacy, and were interpreted by the Japanese as a sign of Western imperialism taking hold of the rest of the Asian continent. Among other measures, they gave the Western nations unequivocal control of tariffs on imports and the right of extraterritoriality to all their visiting nationals. They would remain a sticking point in Japan's relations with the West up to around the start of the 20th century.

Empire of Japan (1868–1945)[edit]

Beginning in 1868, Japan undertook political, economic, and cultural transformations emerging as a unified and centralized state, the Empire of Japan (also Imperial Japan or Prewar Japan). This 77-year period, which lasted until 1945, was a time of rapid economic growth. Japan became an imperial power, colonizing Korea and Taiwan. Starting in 1931 it began the takeover of Manchuria and China, in defiance of the League of Nations and the US. Escalating tension with the U.S.—and western control of Japan's vital oil supplies—led to Japan's involvement in World War II. Japan launched multiple successful attacks on the U.S. as well as British and Dutch territories in 1941–42. After a series of great naval battles, the Americans sank the Japanese fleet and largely destroyed 50 of its largest cities through air raids, including nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrendered in late summer 1945, gave up its overseas holdings in Korea, China, Taiwan and elsewhere, and was occupied and transformed into a demilitarized democratic nation by the U.S.

Historiography of modern Japan[edit]

In Japan, the modern period begins with the Meiji Restoration of the 1860s, marking the rapid modernization by the Japanese themselves along European lines. Much research has focused on the issues of discontinuity versus continuity with the previous Edo (Tokugawa) Period.[79] In the 1960s, younger Japanese scholars led by Irokawa Daikichi reacted against the bureaucratic superstate and began searching for the historic role of the common people. They avoided the elite and focused not on political events but on social forces and attitudes. They rejected both Marxism and modernization theory as alien and confining. They stressed the importance of popular energies in the development of modern Japan. They enlarged history by using the methods of social history.[80]

Representative Western scholars of modern Japan include George Akita,[81] William Beasley, James B. Crowley, John W. Dower, Peter Duus, Carol Gluck, Norman Herbert, John W. Hall, Mikiso Hane, Akira Iriye, Marius Jansen, Edwin O. Reischauer, George B. Sansom, Bernard Silberman, Richard Storry, Karel van Wolfram, and Ezra Vogel.[82][83]

Meiji period[edit]

Renewed contact with the West precipitated a profound alteration of Japanese society. Importantly, within the context of Japan's subsequent aggressive militarism, the signing of the treaties was viewed as profoundly humiliating and a source of national shame. The Tokugawa shōgun was forced to resign, and soon after the Boshin War of 1868, the emperor was restored to power, beginning a period of fierce nationalism and intense socio-economic restructuring known as the Meiji Restoration. The Tokugawa system was abolished, the military was modernized, and numerous Western institutions were adopted–including a Western legal system and quasi-parliamentary constitutional government as outlined in the Meiji Constitution. This constitution was modeled on the constitution of the German Empire. While many aspects of the Meiji Restoration were adopted directly from Western institutions, others, such as the dissolution of the feudal system and removal of the shogunate, were processes that had begun long before the arrival of Perry. Nonetheless, Perry's intervention is widely viewed as a pivotal moment in Japanese history.

Economic modernization[edit]

Japan's industrial revolution began about 1870 as national leaders decided to catch up with the West. The government built railroads, improved roads, and inaugurated a land reform program to prepare the country for further development. Modern industry first appeared in textiles, including cotton and especially silk, which was based in home workshops in rural areas.[84] The government inaugurated a new Western-based education system for all young people, sent thousands of students to the United States and Europe, and hired more than 3,000 Westerners to teach modern science, mathematics, technology, and foreign languages in Japan (O-yatoi gaikokujin).

In 1871 a group of Japanese politicians known as the Iwakura Mission toured Europe and the USA to learn western ways. The result was a deliberate state-led industrialisation policy to enable Japan to quickly catch up. The Bank of Japan, founded in 1877, used taxes to fund model steel and textile factories. Education was expanded and Japanese students were sent to study in the West.[85]

Childhood transformed[edit]

Childhood as a distinct phase of life was apparent in the early modern period, when social and economic changes brought increased attention to children, the growth of schooling and child-centered rituals. A modern concept of childhood emerged in Japan after 1850 as part of its engagement with the West. Meiji-era leaders decided the nation state had the primary role in mobilizing individuals—and children—in service of the state. The Western-style school was introduced as the agent to reach that goal. By the 1890s, schools were generating new sensibilities regarding childhood.[86] After 1890 Japan had numerous reformers, child experts, magazine editors, and well-educated mothers who bought into the new sensibility. They taught the upper middle class a model of childhood that included children having their own space where they read children's books, played with educational toys and, especially, devoted enormous time to school homework. These ideas rapidly disseminated through all social classes.[87][88]

Wars with China and Russia[edit]

Japanese intellectuals of the late-Meiji period espoused the concept of a "line of advantage", an idea that would help to justify Japanese foreign policy around the start of the 20th century. According to this principle, embodied in the slogan fukoku kyōhei, Japan would be vulnerable to aggressive Western imperialism unless it extended a line of advantage beyond its borders which would help to repel foreign incursions and strengthen the Japanese economy. Emphasis was especially placed on Japan's "preeminent interests" in the Korean Peninsula, once famously described as a "dagger pointed at the heart of Japan". It was tensions over Korea and Manchuria, respectively, that led Japan to become involved in the first Sino-Japanese War with China in 1894–1895 and the Russo-Japanese War with Russia in 1904–1905.

The war with China made Japan the world's first Eastern, modern imperial power, and the war with Russia proved that a Western power could be defeated by an Eastern state. The aftermath of these two wars left Japan the dominant power in the Far East with a sphere of influence extending over southern Manchuria and Korea, which was formally annexed as part of the Japanese Empire in 1910. Japan had also gained half of Sakhalin Island from Russia. The results of these wars established Japan's dominant interest in Korea, while giving it the Pescadores Islands, Formosa (now Taiwan), and the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria, which was eventually retroceded in the "humiliating" Triple Intervention.

Over the next decade, Japan would flaunt its growing prowess, including a very significant contribution to the Eight-Nation Alliance formed to quell China's Boxer Rebellion. Many Japanese, however, believed their new empire was still regarded as inferior by the Western powers, and they sought a means of cementing their international standing. This set the climate for growing tensions with Russia, which would continually intrude into Japan's "line of advantage" during this time.

Russian pressure from the north appeared again after Muraviev had gained Outer Manchuria at Aigun (1858) and Peking (1860). This led to heavy Russian pressure on Sakhalin which the Japanese eventually yielded in exchange for the Kuril islands (1875). The Ryūkyū Islands were similarly secured in 1879, establishing the borders within which Japan would "enter the World". In 1898, the last of the Unequal Treaties with Western powers was removed, signaling Japan's new status among the nations of the world. In a few decades by reforming and modernizing social, educational, economic, military, political and industrial systems, the Emperor Meiji's "controlled revolution" had transformed a feudal and isolated state into a world power. Significantly, the impetus for this change was the belief that Japan had to compete with the West both industrially and militarily to achieve equality.

Anglo-Japanese Alliance[edit]

The Anglo-Japanese Alliance treaty was signed with Britain in 1902. It was renewed in 1905 and 1911 before its demise in 1921 and its termination in 1923. It was a military alliance between the two countries that threatened Russia and Germany. Due to this alliance, Japan entered World War I on the side of Great Britain. Japan seized German bases in China and the pacific. The Treaty facilitated cultural and technological exchange between the two countries.[89]

Taishō period[edit]

Emperor Meiji, suffering from diabetes, nephritis, and gastroenteritis, died of uremia. Although the official announcement said he died at 00:42 on 30 July 1912, the actual death was at 22:40 on 29 July.[90][91] After the emperor's death in 1912, the Japanese Diet passed a resolution to commemorate his role in the Meiji Restoration. An iris garden in an area of Tokyo where Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken had been known to visit was chosen as the building's location for the Shinto shrine Meijijingu.

Emperor Taishō then ascended to the throne. The new emperor was kept out of view of the public as much as possible. Having suffered from various neurological problems throughout his life, by the late 1910s, these maladies made it increasingly impossible for him to carry out public functions. On one of the rare occasions he was seen in public, the 1913 opening of the Diet of Japan, he is famously reported to have rolled his prepared speech into a cylinder and stared at the assembly through it, as if through a spyglass. Although rumors attributed this to poor mental condition, others, including those who knew him well, believed that he may have been checking to make sure the speech was rolled up properly, as his manual dexterity was also handicapped.[92]

The reclusive and detached life of Emperor Taishō strongly contrasted with that of the charismatic Emperor Meiji, which lead to the waning imperial power in this period, and the so-called Taishō democracy.

World War I[edit]

Japan entered World War I on the Allied side and declared war on the Central Powers. Though Japan's role was limited largely to seizing German colonial outposts in East Asia and the Pacific, it took advantage of the opportunity to expand its influence in Asia and its territorial holdings in the Pacific. Acting virtually independently of the civil government, the Japanese navy seized Germany's Micronesian colonies. It also attacked and occupied the German coaling port of Qingdao in the Chinese Shandong peninsula.

Japan went to the peace conference at Versailles in 1919 as one of the great military and industrial powers of the world and received official recognition as one of the "Big Five" of the new international order. It joined the League of Nations and received a mandate over Pacific islands north of the Equator formerly held by Germany. Japan was also involved in the post-war Allied intervention in Russia, occupying Russian (Outer) Manchuria and also north Sakhalin (which held Japan's limited oil reserves). It was the last Allied power to withdraw from the interventions against Soviet Russia (doing so in 1925).

The post–World War I era brought Japan unprecedented prosperity.

Early Shōwa period[edit]

In early December 1926, it was announced that Emperor Taishō had pneumonia. Taishō died of a heart attack at 1:25 a.m. in the early morning of 25 December 1926, at the Hayama Imperial Villa at Hayama, on Sagami Bay south of Tokyo (in Kanagawa Prefecture).[93] His son, Emperor Shōwa, commonly known as "Hirohito", assumed the throne that same day. Hirohito would reign for 63 years, through some of both the most tumultuous and prosperous moments in Japanese history.

Fascism in Japan[edit]

During the 1910s and 1920s, Japan progressed towards democracy through movements known as 'Taishō Democracy'. However, parliamentary government was not rooted deeply enough to withstand the economic and political pressures of the late 1920s and 1930s during the Depression period, and its state became increasingly militarized. This was due to the increasing powers of military leaders and was similar to the actions some European nations were taking leading up to World War II. These shifts in power were made possible by the ambiguity and imprecision of the Meiji Constitution, particularly its measure that the legislative body was answerable to the Emperor and not the people. The Kodoha, a militarist faction, even attempted a coup d'état known as the February 26 Incident, which was crushed after three days by Hirohito, the Emperor Shōwa.[94]

Party politics came under increasing fire because it was believed they were divisive to the nation and promoted self-interest where unity was needed. As a result, the major parties voted to dissolve themselves and were absorbed into a single party, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA), which also absorbed many prefectural organizations such as women's clubs and neighborhood associations. However, this umbrella organization did not have a cohesive political agenda and factional in-fighting persisted throughout its existence, meaning Japan did not devolve into a totalitarian state. The IRAA has been likened to a sponge, in that it could soak everything up, but there is little one could do with it afterwards. Its creation was precipitated by a series of domestic crises, including the advent of the Great Depression in the 1930s and the actions of extremists such as the members of the Cherry Blossom Society, who enacted the May 15 Incident.[95]

Second Sino-Japanese War[edit]

Under the pretext of the Manchurian Incident, Lieutenant Colonel Kanji Ishiwara invaded Inner (Chinese) Manchuria in 1931, an action the Japanese government ratified with the creation of the puppet state of Manchukuo under the last Chinese emperor, Pu Yi. As a result of international condemnation of the incident, Japan resigned from the League of Nations in 1933. After several more similar incidents fueled by an expansionist military, the Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937 after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident.[96]

After joining the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1936, Japan formed the Axis Pact with Germany and Italy on September 27, 1940. Many Japanese politicians believed war with the Occident to be inevitable due to inherent cultural differences and ongoing Western imperialism. Japanese imperialism was then justified by the revival of the traditional concept of hakko ichiu, the divine right of the emperor to unite and rule the world, and the practical realities of Japan acting as a liberator for the colonized Asian nations.[97]

Japan was defeated by the Soviet Union in 1938 in localized battles at Battle of Lake Khasan and in 1939 in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol. As the Army did not see a benefit to fighting the Soviet Union, the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact was signed in 1941.[98] The treaty held until August 1945 when the Soviets invaded Manchuria and Korea.

World War II[edit]

Tensions were mounting with the U.S. as a result of a public outcry over Japanese aggression and reports of atrocities in China, such as the infamous Nanjing Massacre. The U.S. strongly supported China with money, airmen, supplies and ongoing diplomatic and economic threats against Japan. In retaliation to the invasion of French Indochina, the U.S. began an embargo on goods such as petroleum and scrap iron products. On July 25, 1941, all Japanese assets in the US were frozen. Because Japan's military strength, especially the mobility of the Navy, was dependent on its now dwindling oil reserves, this action had the contrary effect of increasing Japan's dependence on and need for new acquisitions.

Top civilian leaders, including Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro, believed a war with America would ultimately end in defeat, but felt the concessions demanded by the U.S. would almost certainly relegate Japan from the ranks of the World Powers, leaving it prey to Western collusion. Diplomats offered political compromises in the form of the "Amau Doctrine," dubbed the "Japanese Monroe Doctrine" that would have given the Japanese free rein with regard to war with China. These offers were flatly rejected by the U.S.; the military leaders instead vied for quick military action.[99]

Most military leaders such as Osami Nagano, Kotohito Kan'in, Hajime Sugiyama and Hideki Tōjō believed that war with the Occident was inevitable. On November 1941, they convinced the Emperor to sanction an attack plan against U.S., Great Britain and the Netherlands. However, there were dissenters in the ranks about the wisdom of that option, most notably Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku and Prince Takamatsu. They pointedly warned that at the beginning of hostilities with the US, the Empire would have the advantage and could stay equal in military terms for six months, after which Japan's defeat in a prolonged war with an enemy with a much larger economy would be almost certain.

The Americans were expecting an attack in the Philippines and sent bombers to deter Japan. On Yamamoto's advice, Japan made the decision to attack the main American fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. American strategists believed that Japan would never be so bold as to attack so close to its home base, and the US was taken completely by surprise.[100]

The attack on Pearl Harbor, initially appeared to be a major success that knocked out the American battle fleet—but it missed the aircraft carriers that were at sea and ignored vital shore facilities whose destruction could have potentially crippled US Pacific operations to a much greater extent. Ultimately, the attack inflicted only short-term damage, by immobilizing the battleship fleet, but caused relatively little significant long-term damage. Even worse, the essential Japanese communique announcing the commencement of hostilities to the US government was late in arrival to the White House and was delivered as the attack was underway. This made the Japanese air raid to be perceived as a treacherous sneak attack which provoked the United States to seek revenge in an all-out total war in which no terms short of unconditional surrender would be entertained.

Conquest[edit]

In 1937, the Japanese Army invaded and captured most of the coastal Chinese cities such as Shanghai. Japan also forced France to relinquish (without combat) French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia). After the raid on Pearl Harbor and the entry into the war of the Western Allies, Japan launched quick successful invasions of British Malaya (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore) as well as the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Thailand managed to stay independent by becoming a satellite state of Japan. In December 1941 to May 1942, Japan sank major elements of the American, British and Dutch pacific fleets, captured Hong Kong,[101] the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, and reached the borders of India and Australia.[101] Japan had achieved its primary objective of controlling the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Imperial rule[edit]

The ideology of Japan's colonial empire, as it expanded dramatically during the war, contained two somewhat contradictory impulses. On the one hand, it preached the unity of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a coalition of Asian races, directed by Japan, against the imperialism of Britain, France, the Netherlands, the United States, and European imperialism generally. This approach celebrated the spiritual values of the East in opposition to the crass materialism of the West.[102] In practice, however, the Japanese installed organizationally-minded bureaucrats and engineers to run their new empire, and they believed in ideals of efficiency, modernization, and engineering solutions to social problems. It was fascism based on technology, and rejected Western norms of democracy. After 1945, the engineers and bureaucrats took over, and turned the wartime techno-fascism into entrepreneurial management skills.[103]

Japan would end setting up puppet regimes in Manchuria and China for the duration of the war. The Army operated governments in most of the conquered areas, but paid more favorable attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to obtain oil, but Japan also sponsored an Indonesian nationalist movement under Sukarno.[104] Sukarno finally came to power in the late 1940s after several years of battling the Dutch.[105] The extraction of resources from the Southeast Asian territories would be limited throughout the war primarily by difficulties in transporting them back to the Japanese home islands. This would be particularly true with regard to shipping oil from the Dutch East Indies.

Defeat[edit]

Japan had a clear military advantage following the attack on Pearl Harbor, but as Admiral Yamamoto warned, this would prove to be only temporary. Six months after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy defeated the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Battle of Midway, crippling Japan's offensive capabilities, and firmly establishing America's own military advantage. The war became one of mass production and logistics, and the U.S. effectively funded a far stronger navy with more numerous warplanes, and superior communications and logistics systems. The Japanese had stretched too far and were unable to supply their forward bases, with many of their garrisons under-supplied for the duration of the war. American submarines destroyed a large portion of the Japanese merchant marine, causing a severe shortage of fuel oil for ships, aviation gasoline, and raw supplies for armament production. Japan built warplanes in large quantities but with constant threats necessitating a quick training program, the quality of its pilots continued to diminish,[106] to the point where the Battle of the Philippine Sea was derisively called The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot by American pilots. The Japanese Navy lost a series of major battles, from Midway (1942) to the Philippine Sea (1944) and Leyte Gulf (1944), which put American long-range B-29 bombers in range of the Japanese mainland. A series of massive air raids destroyed much of Tōkyō and other major industrial cities beginning in March 1945 while Operation Starvation seriously disrupted the nation's vital internal shipping lanes. Despite the situation, the Ministers in power generally continued to hold out for a final defence of the homeland that could inflict heavy casualties on the invading Allied troops, in hopes of attaining a negotiated surrender (as opposed to the unconditional surrender being demanded). In August, the two atomic bombs dropped by the United States on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria demonstrated that a negotiated surrender would not be possible, and Japan agreed to the unconditional terms of the Potsdam Declaration.[107]

Total Japanese military fatalities between 1937 and 1945 were 2.1 million; most occurring in the last year of the war. Starvation or malnutrition-related illness accounted for roughly 80 percent of Japanese military deaths in the Philippines, and 50 percent of military fatalities in China. The aerial bombardment by American airmen of a total of 69 Japanese cities appears to have taken a minimum of 400,000 and possibly closer to 600,000 civilian lives (over 100,000 in Tōkyō alone, over 200,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and 80,000–150,000 civilian deaths in the Battle of Okinawa). During the winter of 1945, civilian deaths among settlers and others attempting to return to Japan from Manchuria probably approached 100,000.[108] About 600,000 soldiers were held for two to four years in forced-labor camps in Siberia.[109]

Postwar Japan (1945–present)[edit]

Late Shōwa period[edit]

After the collapse of the Empire of Japan, Japan was transformed into a democratic state with a revised democratic Constitution of Japan. During the postwar period, Japan became an economic power state. This period is characterized by the US-Japan Alliance such as the United States Forces Japan.

Occupation of Japan[edit]

Japan had never been occupied by a foreign power, and the arrival of the Americans with strong ideas about transforming Japan into a peaceful democracy had a major long-term impact. Historian Warren Cohen writes:

- The American occupiers proceeded to demilitarize and democratize Japan with considerable success, largely as a result of Japanese receptivity. Great concentrations of industrial power, the "zaibatsu", were broken up, land redistributed, and organized labor empowered. Visions of a New Deal for Japan emanated from MacArthur's civilian planners in Tokyo.[110]

Japan came under the firm direction of American General Douglas MacArthur. The main American objective was to turn Japan into a peaceful nation and to establish democratic self-government. The occupation transformed the Japanese government into an engine of production, wealth redistribution, and social reform. Political reforms included a freely elected Japanese Diet (legislature) and universal adult suffrage. The Occupation emphasized land reform so that tenant farmers became owners of their rice paddies, and stimulated the formation of powerful labor unions that gave workers a say in industrial democracy. The great zaibatsu business conglomerates were broken up, consumer culture was encouraged, education was radically reformed and democratized, and the Shintō-basis of emperor worship was ended. Historian John Dower says the "visible hand" of New Deal-inspired state leadership, while keeping a capitalist economy, was welcomed by a battered and humiliated Japanese society that was eager to find a peaceful route forward into prosperity.[111]

The reforms were implemented by Japanese officials under American control, so that no Japanese institutions were directly controlled by Americans.[112] While Emperor Hirohito was allowed to retain his throne as a symbol of national unity, actual power was held by complex interlocking networks of elites.[113]

The Empire of Japan was dissolved. Japan was stripped of its overseas possessions and retained only the home islands. Manchukuo was dissolved, and Manchuria and Formosa were returned to China. Korea was occupied and divided by the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The U.S. became the sole administering authority of the Ryūkyū, Bonin, and Volcano Islands, while the USSR took southern Sakhalin and the Kurile islands. Japan vehemently rejects Soviet control of the Kuriles, and diplomatic tension over the issue continued into the 21st century. Shutting down the empire meant that Japanese settlers and officials had to leave. In all, Japanese repatriation centers handled over 7 million expatriates returning to Japan.[114]

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tōkyō Trial), an international war crimes tribunal, was held, in which seven politicians were executed. Emperor Hirohito was not convicted, but instead was turned into a figurehead emperor.[115][116]

Shigeru Yoshida (1878–1967) played the central role as prime minister between 1946 and 1954 (with one interruption). His goal was rapid rebuilding Japan and cooperation with the American Occupation. He led Japan to adopt the “Yoshida Doctrine”, based on three tenets: economic growth as the primary national objective, no involvement in international political-strategic issues, and the provision of military bases to the United States. The Yoshida Doctrine proved immensely successful.[117][118]

The historiography before 1980 was celebratory, and focused on the success of the American occupation in transforming Japan in terms of democracy and freedom. Since the 1980s historians more often stress the limitations of the occupation's reforms and argue that they partly reflected prewar and wartime Japanese innovations.[119]

Dower explains the factors that promoted the success of the American occupation:

- "Discipline, moral legitimacy, well-defined and well-articulated objectives, a clear chain of command, tolerance and flexibility in policy formulation and implementation, confidence in the ability of the state to act constructively, the ability to operate abroad free of partisan politics back home, and the existence of a stable, resilient, sophisticated civil society on the receiving end of occupation policies—these political and civic virtues helped make it possible to move decisively during the brief window of a few years when defeated Japan itself was in flux and most receptive to radical change."[120]

Peace treaty[edit]

Entering the Cold War with the Korean War, Japan came to be seen as an important ally of the US government. Political, economic, and social reforms were introduced, such as an elected Japanese Diet (legislature) and expanded suffrage. The country's constitution took effect on May 3, 1947. The United States and 45 other Allied nations signed the Treaty of Peace with Japan in September 1951. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on March 20, 1952, and under the terms of the treaty, Japan regained full sovereignty on April 28, 1952.

Under the terms of the peace treaty and later agreements, the United States maintains naval bases at Sasebo, Okinawa and at Yokosuka. A portion of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, including one aircraft carrier (currently USS George Washington (CVN-73)), is based at Yokosuka. This arrangement is partially intended to provide for the defense of Japan, as the treaty and the new Japanese constitution imposed during the occupation severely restrict the size and purposes of Japan Self-Defense Forces in the modern period.

Cold War[edit]

After a series of realignment of political parties, the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the leftist Social Democratic Party (SDP) were formed in 1955. The political map in Japan had been largely unaltered until the early 1990s and LDP had been the largest political party in the national politics.[121][122] LDP politicians and government bureaucrats focused on economic policy. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Japan experienced its rapid development into a major economic power, through a process often referred to as the Japanese post-war economic miracle.

Japan's biggest postwar political crisis took place in 1960 over the revision of the Japan-United States Mutual Security Assistance Pact. The new Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which renewed the United States role as military protector of Japan, was pushed through the Diet in 1960 by LDP Prime Minister Eisaku Sato against the strong opposition of minority parties. Opponents on the left responded with massive street protests and political upheaval occurred, and the cabinet resigned a month after the Diet's ratification of the treaty. Thereafter, political turmoil subsided. Japanese views of the United States, after years of mass protests over nuclear armaments and the mutual defense pact, improved by 1972 with the reversion of United States-occupied Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty and the winding down of the Vietnam War.[123]

Japan had reestablished relations with the Republic of China after World War II, and cordial relations were maintained with the nationalist government when it was relocated to Taiwan, a policy that won Japan the enmity of the People's Republic of China, which was established in 1949. After the general warming of relations between China and Western countries, especially the United States, which shocked Japan with its sudden rapprochement with Beijing in 1971, Tōkyō established relations with Beijing in 1972. Close cooperation in the economic sphere followed. Japan's relations with the Soviet Union continued to be problematic after the war, but a Joint Declaration between Japan and the USSR ending the state of war and reestablishing diplomatic relations was signed October 19, 1956.[124] The main object of dispute was the Soviet occupation of what Japan calls its Northern Territories, the two most southerly islands in the Kurils (Etorofu and Kunashiri) and Shikotan and the Habomai Islands, which were seized by the Soviet Union in the closing days of World War II.

Economic growth[edit]