User:Twyatt5/sandbox

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | jem-SEYE-tə-been |

| Trade names | Gemzar, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <10% |

| Elimination half-life | Short infusions: 32–94 minutes Long infusions: 245–638 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

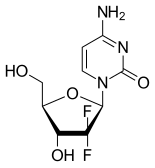

| Formula | C9H11F2N3O4 |

| Molar mass | 263.198 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Gemcitabine (2', 2'-difluoro 2'deoxycytidine, dFdC), orginally sold as Gemzar and subsequently under other labels, is a antimetabolite chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of types of cancer. This includes breast cancer, ovarian cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, and biliary tract cancer. [1] It is used by injection into a vein.[2] [3] [4] It is given via injection into a vein over a short period of time, usually 30 minutes and never more than 60 minutes [2][5].

Gemcitabine is a synthetic pyrimidine nucleoside prodrug[2]. It acts be being incorporated into a cell’s DNA, thus disrupting DNA replication and resulting in cell death[2][3]. It cannot distinguish between cancerous and noncancerous cells and thus resulting common side effects include nausea, fever, rash, shortness of breath, hair loss, and tiredness[2].

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, liver problems, nausea, fever, rash, shortness of breath, and hair loss. Other severe side effects include kidney problems and allergic reactions. Use during pregnancy will likely result in harm to the baby. Gemcitabine is in the nucleoside analog family of medication. It works by blocking the creation of new DNA, which then results in cell death.[2] Because cancer cells are usually growing at a faster rate than normal cells in the body, gemcitabine is incorporated into cancer cells at a higher rate, resulting in cancer cell death.

Gemcitabine was patented in 1983 and was approved for medical use in 1995.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[7] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 24.41 to 316.99 USD per gm vial.[5] In the United Kingdom a gm vial costs the NHS about 155.00 pounds.[8]

History[edit]

Gemcitabine was first synthesized in Larry Hertel's lab at Eli Lilly during the early 1980s. It was intended as an antiviral drug, but preclinical testing showed that it killed leukemia cells in vitro.[9] During the early 1990s, gemcitabine was studied in clinical trials in the United States and approved by the FD in 1996 first for pancreatic cancers. The pancreatic cancer trials revealed that receiving a regimen of gemcitabine increased patient’s one-year survival time significantly as compared to those without it. In 1998, gemcitabine received approval for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. In 2004, it was approved for metastatic breast cancer.[2] [9]

European labels were harmonized by the EMA in 2008.[10]

By 2008, Lilly's worldwide sales of gemcitabine were about $1.7 billion; at that time its US patents were set to expire in 2013 and its European patents in 2009.[11] The first generic launched in Europe in 2009,[12] and patent challenges were mounted in the US which led to invalidation of a key Lilly patent on its method to make the drug.[13][14] Generic companies started selling the drug in the US in 2010 when the patent on the chemical itself expired.[14][15] Patent litigation in China made headlines there and was resolved in 2010.[16]

Medical uses[edit]

Gemcitabine is used in various carcinomas: non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer and breast cancer. It is being investigated for use in esophageal cancer, and is used experimentally in lymphomas and various other tumor types.[citation needed]

Gemcitabine is administered by the intravenous route, since it is extensively metabolized by the gastrointestinal tract.[17]

Bladder cancer[edit]

Gemcitabine became first line treatment for bladder cancer Stage 4 with metastases in combination with cisplatin after a study in 2000 with 405 patients showed similar efficacy but less toxicity compared to the former MVAC regimen.[18] This new CG-regimen involves taking cisplatin on day 2 and taking gemcitabine on days 1, 8, and 15.

Ovarian cancer[edit]

In July 2006 the FDA approved gemcitabine for use with carboplatin in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer that has relapsed at least 6 months after completion of platinum-based (e.g., carboplatin or cisplatin) therapy. Neutropenia was the most commonly reported adverse effect (90% of patients). Other serious adverse effects were mostly hematologic.

Lung cancer[edit]

GemCarbo chemotherapy, consisting of a combination of gemcitabine and carboplatin, is used to treat several different types of cancer, but is most commonly used to treat lung cancer.[19] GemCarbo chemotherapy is usually given as a day patient treatment, involving a blood test the day before, and the drugs are given by an infusion. The GemCarbo regimen is given as a 21-day cycle and on the first day of treatment the patient is given both the gemcitabine and carboplatin. On the same day of the following week (day eight) there is a drip of gemcitabine only. There then follows a rest period of two weeks which completes one cycle of chemotherapy. The next cycle of treatment is given after a rest period, which will be three weeks after the first injection. Usually 4–6 cycles of treatment are given over a period of 3–4 months and this makes up a course of treatment.

Pharmacology[edit]

Chemically gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog in which the hydrogen atoms on the 2' carbon of deoxycytidine are replaced by fluorine atoms.[2][3][4]

As with fluorouracil and other analogues of pyrimidines, the triphosphate analogue of gemcitabine replaces one of the building blocks of nucleic acids, in this case cytidine, during DNA replication. The process arrests tumor growth, as only one additional nucleoside can be attached to the "faulty" nucleoside, resulting in apoptosis.

Another target of gemcitabine is the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). The diphosphate analogue binds to RNR active site and inactivates the enzyme irreversibly. Once RNR is inhibited, the cell cannot produce the deoxyribonucleotides required for DNA replication and repair, and cell apoptosis is induced.[20]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Gemcitabine (dFdC) is a deoxycytidine analog that prevents DNA replication and ultimately causes apoptosis, or cell death. Because cancer cells usually grow at a much faster rate than normal, health body cells, gemcitabine therefore impacts cancer cells (which need to do large amounts of DNA replication) at a higher rate. However, it is a prodrug, meaning it requires chemical modification once it enters the cell before it becomes "active" (able to functionally kill cells).[21][22]

Gemcitabine is hydrophilic and must be transported into cells via molecular transporters for nucleosides (the most common transporters for gemcitabine are SLC29A1 SLC28A1, and SLC28A3).[21][22] After entering the cell, gemcitabine is first modified by attaching a phosphate to it, and so it becomes gemcitabine monophosphate (dFdCMP).[21][22] This is the rate-determining step that is catalyzed by the enzyme deoxycytidine kinase (DCK).[21][22] This means that the first modification to gemcitabine, the addition of the a phosphate, is the slowest step in the process gemcitabine goes through to become chemically active. Two more phosphates are added by other enzymes. After the attachment of the three phosphates Gemcitabine is finally pharmacologically active as gemcitabine triphosphate (dFdCTP).[21] After being phosphorylated, gemcitabine can masquerade as cytidine and be incorporated into the DNA as the cell grows (S-phase replication).[2][21][22]

When gemcitabine is incorporated into a growing cell’s DNA it allows a native, or normal, nucleoside base to be added next to it. This leads to “masked chain termination” as gemcitabine is a “faulty” base, but due to it’s neighboring native nucleoside it eludes the cell's normal repair system (base-excision repair). Thus, incorporation of gemcitabine into the cell's DNA creates a irreparable error that leads to inhibition of further DNA synthesis, and thereby leading to cell death.[2][21][22] Meanwhile, the gemcitabine that had only two phosphates attached (dFdCDP) inhibits nucleotide enzymes. This means that the cell will have trouble making some of the essential molecules it needs to grow and make DNA. This leads the cell to uptake more of these components, which include gemcitabine, from outside the cell. Increased uptake of gemcitabine then decreases time until cell death.[2][21][22] Thus, even though a majority (roughly 90%) of gemcitabine that is taken into a cell is deactivated or destroyed before it can impact the cell, the combination of its two pathways of action lead to its strong effects against cancer.[2][21][22]

Pharmacogenomics[edit]

Since gemcitabine is a prodrug that relies on the actions of specific proteins in cell walls and within the cell for its effectiveness, it does have the potential to be specifically tailored to patients.[23] However, due to small sample sizes of patients and gemcitabine use in tandem with other drugs makes it hard to study this application.[23] It is already known that variation in the expression of the genes (SLC29A1, SLC29A2, SLC28A1,SLC28A3) used for transport of gemcitabine into the cell lead to variations in its potency. Similarly, the genes that lead to its inactivation (DCTD, DCA, NT5C) and the gemes coding for its intracellular enzyme targets (RRM1, RRM2, RRM2B) lead to variations in patient responses.[23] Patients have been know to have, or to acquire, hypersensitivity to gemcitabine.[23] [24]

Side effects[edit]

In general, gemcitabine can reduce the body's white blood cell count, a condition called neutropenia, and thus make people who take it susceptible to infection.[25] It is important that if patients contact the hospital if they experience a fever over 99.5 degrees F (or 37.5 degrees C) or other symptoms of an infections (such as shakiness, chills, or a sore throat).[25]

Common[edit]

- Bruising and bleeding - Gemcitabine can reduce the number of platelets in the blood, thus making it harder for blood to clot and resulting in an increase in bruises, nosebleeds, and bleeding gums.

- Anaemia - This is a low number of red blood cells in the blood and meaning less oxygen can be circulated in the body. This leads to tiredness and breathlessness among other things.

- Nausea and other sickness related feelings

- Loss of appetite

- Breathlessness - May result separately from anaemic symptoms.

- Changes in kidneys and liver work - Gemcitabine can affect how the kidneys and liver function, however these changes are mild and usually go back to normal after treatment ends.

- Fluid Build-up - Also known as edema, this is swelling in the face, ankles, and legs as excess fluid builds up in the body.

- Skin Changes - Gemcitabine sometimes causes dry skin or the occurrence of a rash.

- Hair loss - This can range from thinning hair to losing all of the hair from the head. This usually occurs after the first or second cycle of chemotherapy and is usually temporary.

- Tiredness - A very common side effect that usually worsens over the course of treatment and is due to gemcitabine not being able to distinguish between cancerous and normal cells so it ends up attacking both.[25]

Less common[edit]

- Sore Mouth - The mouth can feel generally sore and ulcers may develop.

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Aching or other muscle and joint pain[25]

Rare[edit]

Gemcitabine can cause other severe or life-threatening effects such as respiratory failure, liver toxicity, capillary leakage, and schedule-dependent toxicity among others.[24]

Taking gemcitabine can also affect fertility, sex life, and periods. Additionally, it is also advised that women taking gemcitabine do not try and conceive and that pregnant or breastfeeding women do not take it.[25] As well, up until now there has been no drug interaction studies conducted but gemcitabine may produce additional effects when taken with other drugs.[24]

Chemistry[edit]

Synthesis[edit]

The synthesis described and shown below is the original synthesis done in the Eli Lilly Company labs. Synthesis begins with enantiopure D-glyceraldehyde (R)-2 as the starting material which can made from D-mannitol in 2-7 steps. Then fluorine is introduced by a "building block" approach using ethyl bromoidfluroacetate. Then, reformatsky reaction under standard conditions will yeild a 3:1 anti/syn diastereomeric mixture, with one major product. Separation of the diastereomers is carried out via HPLC,thus yielding the anti-3 gemcitabine in a 65% yield.[3][4] At least two other full synthesis methods have also been developed by different research groups after Lilly's patent ran out. [4]

Toxicity[edit]

No studies have been done to evaluate exact toxic doses to humans. However, gemcitabine should be given via intravenous drip over the course of 30-60 minutes, but no faster than 30 minutes and no more than once a week during any course of treatment.[24] The following is the recommendations from the manufacturer of Gemzar for its use:[24]

- Ovarian Cancer: 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on Days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle.

- Breast Cancer: 1250 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on Days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle.

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on Days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle or 1250 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on Days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle.

- Pancreatic Cancer: 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes once weekly for the first 7 weeks, then one week rest, then once weekly for 3 weeks of each 28-day cycle.

Research[edit]

Pancreatic cancer[edit]

A study reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2007 suggested that gemcitabine showed benefit in patients with pancreatic cancer who were felt to have successful tumor resections.[26]

The addition of capecitabine to gemcitabine was studied in the ESPAC-4 trial and found beneficial.[27][28]

Other[edit]

Gemcitabine was also investigated for advanced cancer of the biliary tract and gallbladder and was found to have a modest effect on the tumor when combined with cisplatin (NEJM 2010).

As with many nucleoside analogues, gemcitabine may show antiviral activity as well as anti-cancer properties. Preliminary in vitro and mouse studies have shown it to be effective against enteroviruses such as coxsackievirus and poliovirus, as well as showing weaker activity against rhinoviruses, influenza and HIV, though it remains unclear whether gemcitabine is safe and effective enough in these applications to be developed for medical use as an antiviral agent.[29][30][31][32]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ National Cancer Institute. "FDA Approval for Gemcitabine Hydrochloride". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Gemcitabine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Kylie; Weymouth-Wilson, Alex; Linclau, Bruno (2015). ""A linear synthesis of gemcitabine". Carbohydrate research (406): 71–75.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Brown, Kylie; Dixey, Micheal; Weymouth-Wilson, Alex; Linclau, Bruno (2014). "The synthesis of gemcitabine". Carbohydrate research (387): 59–73.

- ^ a b "Gemcitabine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 511. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 590. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ a b Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. p. 259. ISBN 0-471-89979-8.

- ^ "Gemzar". European Medicines Agency. 24 September 2008.

- ^ Myers, Calisha (18 August 2009). "Patent for Lilly's cancer drug Gemzar invalidated". FiercePharma.

- ^ Myers, Calisha (13 March 2009). "Gemcitabine from Actavis launched on patent expiry in EU markets". FierceBiotech.

- ^ Holman, Christopher M. (Summer 2011). "Unpredictability in Patent Law and Its Effect on Pharmaceutical Innovation" (PDF). Missouri Law Review. 76 (3): 645–693.

- ^ a b Ravicher, Daniel B. (28 July 2010). "On the Generic Gemzar Patent Fight". Seeking Alpha.

- ^ "Press release: Hospira launches two-gram vial of gemcitabine hydrochloride for injection". Hospira via News-Medical.Net. 16 November 2010.

- ^ Wang, Mei-Hsin; Alexandre, Daniele (2015). "Analysis of Cases on Pharmaceutical Patent Infringement in Great China". In Rader, Randall R.; et al. (eds.). Law, Politics and Revenue Extraction on Intellectual Property. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 9781443879262.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor1-first=(help) - ^ Chu E., DeVita V. T., "Physicians' Cancer Chemotherapy Drug Manual, 2007", Jones & Bartlett, 2007.

- ^ Von Der Maase, H; Hansen, SW; Roberts, JT; Dogliotti, L; Oliver, T; Moore, MJ; Bodrogi, I; Albers, P; et al. (2000). "Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study". J Clin Oncol. 18 (17): 3068–77. PMID 11001674.

- ^ Macmillan GemCarbo chemotherapy

- ^ Cerqueira NM, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ (2007). "Understanding ribonucleotide reductase inactivation by gemcitabine". Chemistry: A European Journal. 13 (30): 8507–15. doi:10.1002/chem.200700260. PMID 17636467.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alvarellos, ML; Lamba, J; Sangkuhl, K; Thorn, CF; Wang, L; Klein, DJ; Altman, RB; Klein, TE (November 2014). "PharmGKB summary: gemcitabine pathway". Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 24 (11): 564–74. PMC 4189987. PMID 25162786.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mini, E; Nobili, S; Caciagli, B; Landini, I; Mazzei, T (May 2006). "Cellular pharmacology of gemcitabine". Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 17 Suppl 5: v7-12. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdj941. PMID 16807468.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Alvarellos 2014 summarywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Eli Lilly and Company. "Gemzar". Eli Lilly and Company. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Macmillan Cancer Support. "Gemcitabine". Macmillan Cancer Support. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. (January 2007). "Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 297 (3): 267–77. doi:10.1001/jama.297.3.267. PMID 17227978.

- ^ Trial Sets New Standard for Pancreatic Cancer - Adjuvant combination almost doubled 5-year survival. June 2016

- ^ ESPAC-4: A multicenter, international, open-label randomized controlled phase III trial of adjuvant combination chemotherapy of gemcitabine (GEM) and capecitabine (CAP) versus monotherapy gemcitabine in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. June 2016

- ^ Clouser CL, Holtz CM, Mullett M, Crankshaw DL, Briggs JE, O'Sullivan MG, Patterson SE, Mansky LM. Activity of a novel combined antiretroviral therapy of gemcitabine and decitabine in a mouse model for HIV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Apr;56(4):1942-8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06161-11. PMID 22271861

- ^ Denisova OV, Kakkola L, Feng L, Stenman J, Nagaraj A, Lampe J, Yadav B, Aittokallio T, Kaukinen P, Ahola T, Kuivanen S, Vapalahti O, Kantele A, Tynell J, Julkunen I, Kallio-Kokko H, Paavilainen H, Hukkanen V, Elliott RM, De Brabander JK, Saelens X, Kainov DE. Obatoclax, saliphenylhalamide, and gemcitabine inhibit influenza a virus infection. J Biol Chem. 2012 Oct 12;287(42):35324-32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392142. PMID 22910914

- ^ Kang H, Kim C, Kim DE, Song JH, Choi M, Choi K, Kang M, Lee K, Kim HS, Shin JS, Kim J, Han SB, Lee MY, Lee SU, Lee CK, Kim M, Ko HJ, van Kuppeveld FJ, Cho S. Synergistic antiviral activity of gemcitabine and ribavirin against enteroviruses. Antiviral Res. 2015 Dec;124:1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.10.011. PMID 26526589

- ^ Zhang Z, Yang E, Hu C, Cheng H, Chen CY, Huang D, Wang R, Zhao Y, Rong L, Vignuzzi M, Shen H, Shen L, Chen ZW. Cell-based high-throughput screening assay identifies 2', 2'-difluoro-2'-deoxycytidine Gemcitabine as potential anti-poliovirus agent. ACS Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 12. PMID 27733043