User:Trillkat/sandbox

Camp Hereford | |

|---|---|

Prisoner of war camp | |

Camp Hereford Italian Prisoner of War Memorial Chapel | |

| Coordinates: 34°44.746′N 102°25.496′W / 34.745767°N 102.424933°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Opened | 1943 |

| Closed | 1946 |

| Founded by | United States Army |

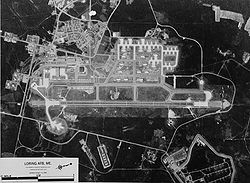

| Loring Air Force Base | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Limestone Air Force Base | |||||||||

| Limestone and Caswell, Maine in United States | |||||||||

USGS 1970 Aerial Photo | |||||||||

Logo of Air Combat Command | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 46°56′59″N 67°53′20″W / 46.94972°N 67.88889°W | ||||||||

| Type | Air Force Base | ||||||||

| Area | 9,000 acres (3,600 ha; 14 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||

| Owner | United States Air Force | ||||||||

| Operator | 42nd Bomb Wing | ||||||||

| Controlled by | |||||||||

| Open to the public | Yes | ||||||||

| Stations | Caribou Air Force Station (East Loring), Caswell Air Force Station | ||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||

| Built | 1947–1953 | ||||||||

| Built by | United States Army Corps of Engineers | ||||||||

| In use | 1950–1994 | ||||||||

| Fate | Mainly intact, partial demolition | ||||||||

| Events | Cold War | ||||||||

| Garrison information | |||||||||

| Current commander | Robert J. Pavelko | ||||||||

| Garrison | 42nd Bomb Wing | ||||||||

| Occupants | 69th Bombardment Squadron, 70th Bombardment Squadron, 75th Bombardment Squadron, 42d Air Refueling Squadron, 407th Air Refueling Squadron, 2192nd Communications Squadron, 101st Fighter Squadron | ||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: KLIZ, ICAO: LIZ | ||||||||

| Elevation | 746 feet (227 m) AMSL | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Camp Hereford, the Hereford Internment Camp, or the Hereford Military Reservation and Reception Center was an American prisoner-of-war camp that housed Italian prisoners during World War II. The camp was located about 3 miles (4.83 km) south of Hereford, Texas, and was the second largest prisoner-of-war camp in the United States,[1] capable of housing nearly 6,000 prisoners as well as 750 American military personnel. It was constructed in 1942 and began housing inmates in 1943. By February 1946 all prisoners of war had been repatriated and the camp was placed on the surplus list.

History[edit]

In June 1942, the War Department authorized the building of Camp Hereford on a section of land along the border of Castro and Deaf Smith counties. The War Department purchased 330 acres (1.3 km2) of farmland from Loyal B. Holland for $14,375, and bought a neighboring half-section of land from Walter N. Hodges for $16.475,[2] ground was broken in July 1942.[1] The 3,000-man camp was to be completed in November, but additions to the camp were requested and the completion date was pushed back to February 1943.[3] The federal government awarded the building contract to the Russell J. Brydan Company of Dallas, with architectural design by the Fort Worth firm of Freese and Nichols. Water and gas lines were laid by another Fort Worth company, Sherman and Erbett; while electricity was provided by the American District Telegraph Company of Texas.[4] It took a work force of around 1,000 people to build the camp. Some laborers were locals and worked on the project when time from their other duties allowed them, but the majority of laborers were from out-of-town and resided on the camp in the barracks they had constructed. Food for the workers was provided by a local restaurant.[5] The construction was supervised by the Army Corps of Engineers, and the total cost of the project was $2 million.[1]

The camp consisted of four compounds: three for enlisted men and one for officers, with additional quarters for U.S. military personnel. Each compound had enough barracks to house around 1,000 men.[6] Upon completion, Camp Hereford was capable of housing 4,800 enlisted men, 1,000 officers, and the American soldiers needed to operate the facility.[3] Although the buildings were designated as temporary structures, Camp Hereford was constructed as a maximum security facility and precautions were made to prevent escape.[1] Each compound was fenced in, and the entire complex itself was surrounded by an electric fence; guards, armed with machine guns and rifles, were stationed in towers along the perimeter of the prison and given orders to fire on any prisoner caught between the two fences.[6] Each guard tower was occupied by at least two men at all times, and was equipped with a loudspeaker and floodlights. The towers were connected to one another (and the captain of the guard) by telephone and were spaced in such a way as to give the guards clear sightlines and firing lines.[7]

Camp Hereford was a base camp, meaning a large facility capable of holding anywhere from 3,000 to 6,000 prisoners, which provided workers for smaller branch camps located in and around the Texas Panhandle. Base camps were typically located in rural areas in order to make escape more difficult, and also so that prison labor could be more easily exploited by rural farmers and businesses (civilian labor being in short supply due to the war effort). Camp Hereford was one of only a handful of base camps constructed on private property in Texas specifically for the housing of prisoners-of-war, most of the other base camps in Texas were located on already existing military bases.[8] It was the only base camp in Texas for Italian prisoners-of-war and also "the camp to which hard-core Fascists and troublemakers were sent".[9] A group of German prisoners was briefly sent to Camp Hereford, but they were quickly removed when rioting broke out between them and the Italians who were already there.[6]

Upon arrival to the United States, Axis prisoners were to be showered and deloused at the port in which they arrived, but these procedures were not often followed. Instead, wearing the uniforms in which they had been captured, many were led onto trains and sent directly to their assigned prison camps.[10] The first prisoners to arrive at Camp Hereford, in the spring of 1943, were Italian soldiers captured during the African Campaign. They disembarked from the train at Summerfield, Texas and were marched 8 miles (12.87 km) to the new camp, residents remember the soldiers sang "Rosamunde" as they marched.[6] Once in camp, after being fed and allowed to shower, the prisoners experienced a restless few days in which they were assigned barracks, vaccinated, examined by a doctor, interviewed, and given a serial number. All prisoners were issued "underwear (four pair), socks (four pair), a belt, a cap, coat, gloves, [and] overcoat".[11] If it was in good shape, enlisted men had their national uniform marked with the letters "PW"; if their uniform was in poor condition they were issued two pairs of pants and two shirts with the "PW" marking. The clothing of officer prisoners was not marked.[12]

All prisoners received a monthly allowance in scrip which could be redeemed at the canteen or post exchange; prisoners were not allowed to have any real money in their possession.[13] These monthly credits "ranged from $3 for an enlisted man to $20 for a lieutenant, $30 for a captain, and $40 for a major and any higher rank."[14] According to the Geneva Conventions officer prisoners could not be forced to do work of any kind, while non-commissioned officers could be tasked with supervisory or administrative roles. Enlisted prisoners, however, could be required to work, and they made up the bulk of the camp's labor force. Prisoners performed routine tasks typical of the maintenance, cleaning, and operation of any military post including kitchen duty, garbage detail, basic repair work, and any number of other daily chores; this work was unpaid.[13] Any work performed beyond this regular maintenance was to be paid according to the Geneva Conventions. Prisoners could volunteer to do paid work at a rate of $0.10 per hour paid in scrip, which was the going rate of pay for an American private. Although prisoners with special skills could perform paid tasks around the camp, the bulk of paid work was contract labor outside of camp for local farmers and businesses. In order to secure a contract for prison labor, farmers filled out a certificate of need from the War Manpower Commission and the prisoners were then allocated by the Extension Service of the Department of Agriculture on a county level.[15] Prisoners from Camp Hereford performed all types of agricultural work in the surrounding community including processing carrots, picking cotton, and sacking potatoes and onions. They also poured concrete for the grain elevators at Pitman Grain.[16]

There were identical dining halls in each compound. Each one had a kitchen with a large refrigerator which was separated from the dining area by a counter. In order to prevent food waste from serving prisoners unfamiliar foods, the prisoners (under the supervision of the camp mess officer) were allowed to prepare their meals according to their national tastes.[17][18] Early on in the war, the United States closely followed Article 11 of the Geneva Conventions which stipulated that prisoners of war be given food "equal in quality and quantity to that supplied to American troops."[19] A reporter in July of 1943 found that apple butter, tomatoes, tomato sauce, and ketchup were among the preferred foods of the inmates. Breakfast that day consisted of cereal, fruit, eggs, milk, bread, tea, and apple butter. For dinner beans, cabbage, beef with gravy and tomato sauce, beets, bread, tea, and more apple butter was served. And for supper, polenta, tomato sauce, cabbage, apple butter, and lemonade.

3 camp newspapers: Il Powieri (derived from POW) for general news, Argomenti for literature and politics, and Olympia for sports. Also report of shortwave radio created by prisoners out of regular radio so they could listen to italian programs.[20]

Geneva convention article 11 closely followed for first 3 years

See also[edit]

| Boston Resolutes | |

|---|---|

| Information | |

| League | |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Established | 1870 |

| Disbanded | 1889 |

| League championships | None |

Cuban Giants[edit]

The Cuban Giants were the first fully salaried African-American professional baseball club.[21] The team was originally formed in 1885 at the Argyle Hotel, a summer resort in Babylon, New York. Initially an independent barnstorming team, they played games against opponents of all types: major and minor league clubs, semiprofessional teams, even college and amateur squads. They would go on to join various short-lived East Coast leagues, and in 1888 became the "World Colored Champions". Despite their name, no Cubans played on the team. The "Cubes" remained one of the premier Negro league teams for nearly twenty years, and served as a model that future black teams would emulate.

History[edit]

Name[edit]

Early newspaper accounts mention John Lang (the team's early financial backer) and refer to the team alternately as "Lang's colored giants"[22] or "Lang's Cuban Giants",[23] emphasizing the size of the players, with one newspaper noting that "nearly every man is six feet in height".[24] Jerry Malloy, a baseball journalist and researcher, believes that the team was likely named after the National League's New York Giants;[25] while Michael E. Lomax theorizes that they may have considered themselves "giants among the black independents"[26] of the era because they were born out of a merger of three separate teams. Opinions also differ on how the word "Cuban" came to be used. There were no Cubans on the team, although a handful of players had played in Cuba prior to the creation of the team. The team would go on to play in Cuba, but the name predates those eventual trips. Malloy states that "avoiding the opprobrium of hostile white Americans by 'passing' as Cubans may have been a factor in naming the team"[27][a] and that it might have been easier for management to schedule games if the team was seen as being "comprised of Cubans rather than African Americans".[29] Lomax finds this reasoning to be problematic since it was widely known at the time that the team was made up of black players; according to him this reasoning "suggests that the Cubans were cowards and ashamed of their cultural heritage."[26] Rather, Lomax believes the key to understanding "Cuban" lies in the team's status as both competitors and entertainers, as well as their skin color:

In terms of skin color, virtually every player, not to mention the ones who played in organized baseball, was a light-skinned black. Thus, the name 'Cuban' could have referred to their mulatto status, a stage name exemplifying their vaudevillian flair on the diamond instead of signifying their racial or ethnic heritage.[30]

In 1896, unhappy with the ownership of J. M. Bright, several players left the team and were signed by E. B. Lamar Jr. of Brooklyn. This new team of ex-Cuban Giants was christened the "Cuban X-Giants". After the split, Bright's team would often be referred to as the Genuine Cuban Giants or Original Cuban Giants.[31]

Early years[edit]

1885[edit]

In July of 1885, the Keystone Athletics of Philadelphia (an independent black semipro team formed by hotelman Frank P. Thompson) were hired by the Argyle Hotel on Long Island to play baseball for the hotel's guests.[32][b] Later in August the team merged with two other semipro teams: the Orions of Philadelphia, and the Manhattans of Washington D.C. The new team was dubbed the Cuban Giants.[32] S. K. Govern a native of St. Croix, Virgin Islands (formerly of the Manhattans) became the new team's field manager, while John Lang (a white businessman and former owner of the Orions) provided the financial backing.[33] Together, Thompson and Govern developed a plan to keep the team financially secure: play all year. The two men leveraged their personal connections to schedule games during the winter months in Cuba and the newly forming resort hub of St. Augustine, Florida. Playing in Florida was already a well worn practice for Thompson's Athletics: they had played in St. Augustine at the San Marco Hotel during the winter of 1884;[34] and, while evidence is limited, Govern's Manhattans may have played in Cuba as early as 1881 or 1882.[35]The team's future seasons would follow this cycle: from April to October the Giants would implement a "'stay-at-home' travel schedule, playing games in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania";[36] then they would head to Cuba for December and part of January, followed by Florida just in time for the "peak of the hotels' festive winter season."[27]

By the time the Argyle closed for the season on October 1, 1885, the Cuban Giants had won six out of nine games played, losing two and tying one.[37] They headed out on the road and faced their first major league opponent, the New York Metropolitans of the American Association, losing 11–3.[38] On October 10, they faced off against another major leauge opponent: the Philadelphia Athletics. Once again the Giants fell short, losing 13–7, but the final score had little to do with the quality of play according to a correspondent with the Sporting Life:

Had it not been for Johnny Ryan, who officiated as umpire, the Athletics would have stood a good chance of being defeated by nine colored players, or the Cuban Giants as they are called. Lack of experience, weak attempts at running the bases, and the umpire's very partial decisions contributed to the defeat of the colored aggregation.[39]

1886[edit]

The Giants may, or may not, have played in Cuba their first year, but they did make it to Florida;[40] and as they made their way back north that first spring they "played a series of games in every large city from St. Augustine to Philadelphia"[41] winning forty straight games, according to an article in the New York Age. That first road trip ended in Trenton, New Jersey. At the time, Trenton was without a representative in organized baseball: the Trenton Club of the Eastern League had recently relocated to Jersey City. John Lang had decided not to finance the Cuban Giants for the 1886 season, and in April a number of them were signed to the Trenton Browns by Harry Simpson.[42] Through this reorganization of his independent club, Simpson hoped to both renew Trenton's interest in professional baseball and "capitalize on the novelty of a black team playing at a high caliber."[43] His plan paid off almost immediately when his new club beat the Jersey Blues of Hoboken 8–7 at the Chambersbourg Grounds in Trenton on May 3, 1886.[44] Simpson's ownership of the team, however, would be short-lived: their success caught the eye of Walter I. Cook. Later in May, Cook (along with his partner John M. Bright) assumed control of the team with Govern acting as manager.[45][c] Cook came from a wealthy family and was generous to the team with his money, especially when it came to illness or injuries.[46] Cook was so well-liked that Govern and they players arranged a benefit game for him in which they tendered "their services free."[47] According to Heaphy, it was Cook who first established salaries for the players;[21] Sol White describes what the players could expect each week:

At that time salaries were according to position. Mr. Cook gave pitchers and catchers, $18.00 per week and expenses; infielders, $15.00 per week and expenses; outfielders, $12.00 per week and expenses.[48]

Although Cook financed the team, S. K. Govern (and club secretary George Van Sickle) ran the day-to-day operations. Govern "signed players to one-year contracts, utilized the press to schedule games, and was even responsible for selling season tickets."[49] On May 28, 1886 the Cuban Giants played the St. Louis Browns of the American Association at the Chambersbourg Grounds in front of a "good-natured, wildly enthusiastic assemblage of over two thousand people."[50] Despite losing 9–3, the game marked the first time the Giants played for a sold out crowd. Unfortunately, attendance figures like these were the exception, not the rule. As an independent team the Giants could not rely on a fixed schedule of league games, instead Govern booked games himself, offering large guarantees to major league clubs and smaller guarantees to minor league, local, or college teams. Scheduling games with lesser opponents often resulted in lopsided scores and uninteresting games, leading to sporadic home attendance and fluctuating gate receipts. This in turn led the Giants to schedule more road games, often playing weekend games in New York City and Hoboken, New Jersey.[51] Their status as an independent club also meant the Giants were subject to player raids. In June of 1886, Govern signed pitcher George Washington Stovey to a short term contract. Stovey struck out eleven batters in the only game he would play as a Cuban Giant: a 4–3 loss to the Bridgeport team of the Eastern League.[52] Unbeknownst to Govern, it seems Stovey had also signed a contract with the Eastern League's Jersey City Blues. Patrick Powers, manager of the Jersey City Blues, attempted to lure Stovey to his team and break his contract with the Giants with an offer of two hundred dollars per month; Stovey refused. A few days later, Powers went to Trenton with a notice from the Eastern League's president demanding that Stovey report to Jersey City the next day. Powers and the Eastern League essentially coerced the Giants into giving up their claim on Stove: if they tried to enforce their contract with him, Eastern League clubs would refuse to schedule games with them. Unwilling to sacrifice future lucrative bookings with Eastern League teams the Giants relented.[53]

In July of 1886, the Meriden team of the Eastern League disbanded and withdrew from the league mid-season. The Cuban Giants applied to take their spot, hoping that league membership would provide a steady slate of quality opponents as well as protection from player raids. It appeared that the team's application would be accepted, and according to Govern, the only thing that needed to be worked out was whether the Giants would assume the Meriden team's schedule and low position in the standings or be given the opportunity to start fresh.[54] Unfortunately, they were not given the chance: on July 20, the Eastern League rejected the Cuban Giants' application and continued the season with only five teams. Despite the fact that the league already counted black stars like George Stovey, Fleet Walker, and Frank Grant among its ranks, race was a driving factor in barring the Cubes entry. According to the Meriden Journal "the dread of being beaten by the Africans had something to do with the rejection of the application of the Cuban Giants."[55] However, other factors were also at play: the Eastern League's 1886 season was a financial disaster brought on by "bad management, and an entire lack of harmony among the clubs"[56] Indeed, two other teams had already withdrawn from the league by the time the Meriden squad dropped out in July. Moreover, because the Eastern League was a party to the National Agreement its members had to abide by the National League's rule forbidding league clubs from scheduling games on Sundays. The Cuban Giants were reluctant to give up their profitable weekend bookings in Hoboken and New York, and this also played a part in the Eastern League's decision to reject their application.[57]

Hoping to boost attendance figures and protect the team from player raids, the Cuban Giants attempted to join the Eastern League in July of 1886 when the Meriden, Conneticut team withdrew mid-season.

1887[edit]

In 1887, hoping to increase home attendance, Walter Cook and his partner J. M. Bright relocated the team from the Chambersbourg Grounds to the East State Street cricket grounds where they built a new grandstand that sat fifteen hundred to two thousand people. Meanwhile, S. K. Govern secured leases on the Long Island Eastern League grounds in Brooklyn, the old Polo Grounds, and the Elysian Field in Hoboken which "enabled the Giants to schedule Sunday games against the top clubs in those areas."[58]

J. M. Bright purchased the Cuban Giants from Cook in June 1887. Bright was able to get them into the Middle States League in 1889, as joining a league was something the team had been trying to do for some time. However, Bright was not nearly as well-liked as Cook, and had to deal often with renegade players. This would be the team's last year in Trenton. In 1890 the entire team fled and played as the Colored Monarchs of York, Pennsylvania. In 1891, the heart of the team fled to their rival, Ambrose Davis’ Gorhams of New York City, then called the Big Gorhams.

This dismantling and reassembling of the team became routine year after year until 1896, when E.B. Lamar Jr. from Brooklyn bought the team from Bright, renaming them the Cuban X-Giants. Bright responded by putting together an inferior team calling them the "Genuine Cuban Giants" or the "Original Cuban Giants". The Cuban X-Giants had a successful ten-year run as one of the best black teams in the East.

"The Pride of Havana," Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria

Giants to play a game on August 20, 1886 "complimentary to Manager Cook, the players giving their services free."The visitors beaten[59]

Mr. Cook's benefit "complimentary to Mr. Walter I. Cook, who has been giving the home club their financial support through the season. The benefit was arranged by Mr. Govern, the acting manager, and the players, who will tender their services free. Those who have enjoyed the good sport furnished by Mr. Cook this summer, will doubtless be glad to show by attending to-day their appreciation of his efforts."[60]

Savannah Morning News ad[61]

May 10, 1886 Daily True American (3 references of cubes: 1 ad, 1 box score, 1 article)[62]

Walter cook obit[63]

The Giants Win. May 13, 1886 Daily True American[64]

The team played in Cuba in the winter of 1885–1886[27] and again in the winter of 1886–1887,[65]

Ponce de Leon Hotel[edit]

In the summer of 1885, around the same time the Cuban Giants were being formed, Henry Flagler made the decision to build the Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine. Flagler, a founder of Standard Oil, envisioned the hotel as a place where "he and his wealthy friends could find princely shelter from the harsh winters of the North."[66] The hotel opened three years later on January 10, 1888. Osborn D. Seavey was the manager of the hotel, and had previously been the manager of the San Marco where he likely crossed paths with Frank Thompson. Through this connection with Seavey, Thompson was able to incorporate the Cuban Giants and black baseball into the "integrated network of leisure activities"[67] offered by the hotel. The players were hired as waiters (just as the Athletics had been at the San Marco), but "their primary responsibility was to entertain the guests with their skills on the diamond".[68] An 1889 article from the St. Augustine Weekly News puts it this way:

The colored employees of the Hotel Ponce de Leon will play a game today at the fort grounds with a picked nine from the Alcazar. As both teams possess some of the best colored baseball talent in the United States [,] being largely composed of the famous Cuban Giants, the game is likely to be an interesting one.[66]

On one occasion, unable to schedule a game with a local club, the team played a squad made up of tennis players staying at the hotel.[69] On another occasion, a game played against some of the hotel's guests was attended by ex-President Grover Cleveland at the invitation of Govern. If they could not find a worthy opponent the Giants would play intra-squad games amongst themselves.[70]

In 1889 while at the Ponce de Leon, Thompson put together an organization called the Progressive Association of the United States of America (PAUSA). Thompson was elected president of the organization, and Govern was elected secretary. Ben Holmes, the team's third baseman, was also an active member of the group. Thompson used his position to preach against "the unpardonable sin of racial prejudice practiced in the dining room of the Ponce de Leon"[71] and the Cuban Giants served as an example of the doctrine of racial solidarity and self-help that the group espoused. The racially integrated PAUSA also promoted the idea of black-white cooperation for practical, as well as ideological, reasons: Thompson and Govern's efforts to eliminate racial barriers simultaneously created jobs for their players during the winter, while also promoting "the black game to the white spectator."[72]

Winter[edit]

"The Giants … played a number of winters in Havana, Cuba".[73] The Giants had discovered that the key to being financially stable was to play baseball all year round. Cuba was a perfect place for them to play their winter seasons, because they could avoid the cold temperatures that were common in New Jersey in the winter, and they drew huge crowds when they played in Havana. They were so popular in fact that they played "in front of as many as 15,000 fans".[73] By comparison, the average attendance per game for the Philadelphia Baseball Grounds, a popular baseball venue at the time, in 1890 was 2,231 per game.[74]

1886 in Cuba?[75]

History[edit]

On March 14 and 15, after a series of meetings throughout the winter, team representatives met at the Douglass Institute in Baltimore to finalize the schedule for the new league. Acknowledging the experimental nature of the new league, the various delegates kept the schedule short leaving "plenty of open dates between championship games, so as to permit the clubs to take advantage of every opportunity for exhibition games." [76] "Player salaries were to range from $10 to $75 per month; each club was to hire a local umpire; visiting teams were guaranteed $50 plus half the gate receipts, and were to receive $25 from the home team in case of rainout."[77] They adopted the Reach brand baseball, in return the company would supply the league with two gold medals: one for highest batting average and the other for highest fielding percentage at the end of the season.

The league was organized by Walter S. Brown a newspaperman with the Cleveland Gazette.[78] Brown served as the league president and the business manager of the Pittsburgh club.[79][80] On March 14 and 15, after a series of meetings throughout the winter, team representatives met at the Douglass Institute in Baltimore to finalize the schedule for the new league.[81]. The league consisted of eight teams: The Baltimore Lord Baltimores, Boston Resolutes, Louisville Falls Citys, New York Gorhams, Philadelphia Pythians, Pittsburgh Keystones, Washington Capital Citys, and Cincinnati Browns.[82][83] Neither Washington nor Cincinnati would play a game as they "failed to put up their bonds" at the beginning of the season.[81] On opening day, May 5, 1887 the Lord Baltimores beat the Pythians 15–12.[84]

The league quickly experienced financial problems. Due to the passage of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, railways revoked the reduced "group rates" normally enjoyed by traveling baseball teams. Fares fluctuated wildly and could double or triple overnight, wreaking havoc on the budgets of baseball teams throughout the country (even those in the American Association and the National League). A storm from the west, coupled with the rate hikes, led to disaster for the traveling Boston Resolutes on their way to Louisville. The storm caused the Resolutes to cancel several exhibition games they had planned along the way to help them pay for their trip. They missed their first scheduled game with the Louisville Falls City, and barely arrived for the second on May 7. Apparently unfazed by all the turmoil, the Resolutes beat the Falls City 10–3.[85] Unfortunately, the revenue from the sparsely attended game was not enough to cover the cost of the trip to their next game in Pittsburgh, as a result the Resolutes were stranded in Louisville.[86] The Philadelphia Pythians withdrew from the league after their May 16 game with the Gorhams failed to take in enough money to pay for the use of the Athletics ball park.[87] The league folded after two weeks on May 23.

Schedule[edit]

| Date | Opponent | Result | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 5 | Philadelphia | W 15–12 | |

| May 6 | Philadelphia | W 11–3 | |

| May 9 | at Philadelphia | L 6–26 | |

| May 10 | at Philadelphia | L 9–16 | |

| May 11 | Boston | Forfeit* | Boston stranded in Louisville |

| May 12 | Boston | W Forfeit** | Boston stranded in Louisville |

| May 13 | New York | L 8–15 | |

| May 14 | New York | W 27–9 | |

| May 16 | at Pittsburgh | W 22–10 | |

| May 17 | at Pittsburgh | L 6–9 | |

| May 18 | at Pittsburgh | L 8–16 | |

| May 19 | at Pittsburgh | W 6–2 | |

| *Forfeit declined by Baltimore • **Forfeit accepted by Baltimore | |||

Giacomo Joyce is a posthumously-published work by Irish writer James Joyce. It was published by Faber and Faber from sixteen handwritten pages by Joyce. In the free-form love poem, presented in the guise of a series of notes, Joyce attempts to penetrate the mind of a "dark lady", the object of an illicit love affair.

Giacomo Joyce contains several passages that appear in Joyce’s subsequent works including A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses, and Exiles. Some passages were borrowed verbatim while others were reworked. According to Ellmann, this reflects a decision on Joyce’s part to "pillage rather than publish" Giacomo Joyce.[88]

Writing and publication[edit]

Giacomo Joyce was written in Trieste between 1911 and 1914 shortly before the publication of A portrait of the artist as a young man. The original manuscript contains fifty fragments transcribed onto eight large sheets of sketching paper held within a blue school notebook. It was written in Joyce's "best calligraphic hand". (ellmann) The manuscript was left with his brother Stanislaus when Joyce moved to Zurich in 1915.(delville) The text of Giacomo Joyce is quoted at length in Ellmann's 1959 biography of Joyce, but it wasn't until 1968 that it was published in its entirety.

Giacomo Joyce contains several passages that appear in Joyce’s subsequent works including A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses, and Exiles. Some passages were borrowed verbatim while others were reworked. According to Ellmann, this reflects a decision on Joyce’s part to "pillage rather than publish" Giacomo Joyce.[88] Writer and critic, Michel Delville, asserts that the "explicitly autobiographical character of the poem and the scabrousness of the subject eventually prevented Joyce from publishing"; and that Joyce may have found it "aesthetically embarrassing as well as biographically compromising".

Analysis and interpretation[edit]

The hero of Giacomo Joyce is undoubtedly Joyce himself, and within the text Giacomo is referred to as "Jamesy" and "Jim". There is also a reference to Joyce's wife Nora.[89] Additionally, "Giacomo" is the Italian form of the author's forename, James. According to Helen Barolini, the use of the name Giacomo is an ironic allusion to "the name of another (but more successful) lover, Giacomo Casanova."[90] The "dark lady" at the center of Giacomo Joyce is identified by Ellmann as Amalia Popper.[91] The daughter of Leopoldo Popper, a Jewish businessman who ran a shipping company in Trieste, Amalia was tutored by Joyce between 1908 and 1909.[92] Citing various biographic discrepancies, other scholars dispute that the heroine of Giacomo Joyce is Amalia Popper, rather they say she is most likely an amalgam of several of Joyce's students in Trieste

GJ is displays elements of Imagist poetry (compared to Ezra Pound)

Delville GJ is almost entirely dedicated to the narrator's ever changing perceptions of his pupil whom he perceives now as a charming specimen of fragile adolescent beauty ("Frail gift. Frail giver, frail blueveined child" [Giacomo 3], "A cold frail hand:shyness, silence" [13]); now as a source of deadly threat ("She answers my sudden greeting by turning and averting her black basilisk eyes." / "A starry snake has kissed me: a cold nightsnake. I am lost!" [15]). G's infatuation constantly alternates between patterns of admiration and contempt/domination and submission.

John McCourt describes Giacomo Joyce as "a mixture of several genres — part biography, part personal journal, part lyrical poetry... part prose narrative".[93] It represents the liminal period when Joyce was transitioning from the poetry of Chamber Music to the prose of Ulysses.[94] Several of the shorter fragments in the text closely resemble Ezra Pound's "In a Station of the Metro" which leads Delville to connect it to Imagist poetry, a movement which was well underway at the time of Joyce's writing.[95]

The fifty fragments which make up the text are narrated chiefly in the present tense.

Notes[edit]

- ^ This is the same justification Sol White gave in a 1938 Esquire article: "when that first team began playing away from home, they passed as foreigners—Cubans, as they finally decided—hoping to conceal the fact that they were just American Negro hotel waiters, and talked a gibberish to each other on the field which, they hoped, sounded like Spanish."[28] This account is likely apocryphal as it was not reported in contemporary accounts, nor did it appear in White's own History of Colored Base Ball (1907).[27]

- ^ Sol White's account in his History of Colored Base Ball that Thompson formed the team from waiters and bellhops already employed at the Argyle is also likely apocryphal. Evidence suggests that he got it backwards, according to Malloy "any duties the players performed… as waiters, bellhops, porters and the like were incidental to their primary obligation, which was to play baseball for the hotel’s guests.”[32] This is not surprising considering that White's History was published in 1907, more than three decades after the fact.

- ^ Accounts differ regarding the change in ownership between Simpson and Cook. Malloy states that Simpson sold the team to Cook,[46] while Lomax believes that Cook expressed an interest in buying the team, prompting Govern to negotiate a deal with him unbeknownst to Simpson.[43]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Henegar, Lucielle (1 February 1995). "Hereford Military Reservation and Reception Center". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Rogers 1987, p. 58.

- ^ a b Walker 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Hurt 2008, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Rogers 1987, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Graves 1982, p. 60.

- ^ Rogers 1987, p. 63.

- ^ Walker 1980, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Walker 1980, p. 171.

- ^ Walker 1980, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Walker 1980, p. 114.

- ^ Walker 1980, p. 113.

- ^ a b Rogers 1987, p. 70.

- ^ Keefer 1992, p. 60.

- ^ Rogers 1987, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Rogers 1987, p. 76.

- ^ Rogers 1987, p. 80.

- ^ Walker 1980, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Walker 1980, p. 116.

- ^ Keefer 1992, p. 52.

- ^ a b Heaphy 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "Scratch Hits". The Boston Daily Globe. Vol. XXVIII, no. 64. 2 September 1885. p. 2. Retrieved 27 January 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Baseball Brevities". Hazleton Sentinel. No. 49. Hazleton, Pennsylvania. 21 September 1885. Retrieved 27 January 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dots from Different Diamonds". The Daily Picayune. Vol. XLIX, no. 221. New Orleans, Louisiana. 2 September 1885. Retrieved 27 January 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Malloy 2005, p. 3.

- ^ a b Lomax 2003, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Malloy 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Harlow 1938, p. 75.

- ^ Malloy 1995, p. lxi.

- ^ Lomax 2003, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Malloy 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Malloy 1995, p. lx.

- ^ Browne 2011, p. 55.

- ^ "Note and Comments". The Sporting Life. 5 (3): 7. 29 April 1885. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Costello, Rory (2000). "S. K. Govern". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 50.

- ^ White 1995, p. 8.

- ^ "The Cuban Giants Beaten" (PDF). The New York Times. Vol. XXXV, no. 10637. 6 October 1885. p. 2. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Saturday's Exhibition Games". The Sporting Life. Vol. 6, no. 1. 14 October 1885. p. 1. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 96.

- ^ White 1995, p. 134.

- ^ "Manager Simpson's New Team". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 103. Trenton, New Jersey. 30 April 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ a b Lomax 2003, p. 54.

- ^ "Trenton Victorious". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 106. Trenton, NJ. 4 May 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "To-day's Base Ball". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 113. Trenton, NJ. 12 May 1886. p. 4. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b Malloy 2005, p. 7.

- ^ "Mr. Cook's Benefit". Daily True American. Vol. LI, no. 43. Trenton, NJ. 20 August 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ White 1995, p. 10.

- ^ Lomax 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "Some Good Ball Playing". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 128. Trenton, NJ. 29 May 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Lomax 2003, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Malloy 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 58.

- ^ "On the Diamond". Daily True American. Vol. LI, no. 13. Trenton, NJ. 16 July 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "The Black Nine Rejected". The Meriden Journal. Meriden, CT. 20 July 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 7 March 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Eastern League". Spalding's official base ball guide. Chicago and New York: A. G. Spalding & Bros. 1887. p. 80. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Lomax 2003, pp. 70–71.

- ^ "The Visitors Beaten". Daily True American. Vol. LI, no. 42. Trenton, NJ. 19 August 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Mr. Cook's Benefit". Daily True American. Vol. LI, no. 43. Trenton, NJ. 20 August 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "Old Base Ball Park". Savannah Morning News. Savannah, Georgia. 20 April 1886. p. 2. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "More Base Ball". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 111. Trenton, NJ. 10 May 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Obituary". Daily True American. Vol. LIII, no. 150. Trenton, NJ. 26 June 1888. p. 5. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ "The Giants Win". Daily True American. Vol. L, no. 114. Trenton, NJ. 13 May 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "Base Ball Notes". The Sun. Vol. LIII, no. 314. New York, NY. July 11, 1886. p. 7. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Malloy 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 92.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. xx.

- ^ "Base Ball Notes". Wheeling Sunday Register. Vol. 26, no. 161. Wheeling, West Virginia. 7 April 1889. p. 3. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Browne 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Lomax 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 95.

- ^ a b Heaphy 2003, p. 17.

- ^ "Attendance". Baseball-statistics.com. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Base Ball Notes". The Sun. Vol. LIII, no. 314. New York, NY. July 11, 1886. p. 7. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "The Colored League". The Sporting Life. Vol. 8, no. 24. Philadelphia, PA. 23 March 1887. p. 4. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Malloy, Jerry. "The Pittsburgh Keystones and the 1887 Colored League". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Heaphy, Leslie A. (2003). The Negro leagues, 1869-1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 24. ISBN 9780786413805. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "1887 Season National Colored League". Seamheads.com. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Walter Brown". Seamheads.com. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b Mars, Ken (August 15, 2017). "The 1887 National Colored League Resource Guide". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "The Official LIst". The Sporting Life. Vol. 8, no. 17. Philadelphia, PA. February 2, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Brown, Walter S. (February 9, 1887). "The Colored League". The Sporting Life. Vol. 8, no. 18. Philadelphia, PA. p. 1. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "The Colored League". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. May 6, 1887. p. 6. Retrieved 7 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Boston Resolutes Make Mince-Meat of the Falls City Club". The Courier-Journal. Vol. LXXII, no. 6703. Louisville, Kentucky. 8 May 1887. p. 11. Retrieved 6 January 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Almost Stranded". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Vol. CXVI. 11 May 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 6 January 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Colored League a Failure". The Sporting Life. Vol. 9, no. 8. Philadelphia, PA. 1 June 1887. p. 9. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b Elmann 1968, p. xvi.

- ^ Ellmann 1968, p. xii.

- ^ Barolini, Helen (2003). "The End of My Giacomo Joyce Affair". Southwest Review. 88 (2/3). Southern Methodist University: 249. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Ellmann 1968, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Mahaffey, Vicki (Spring–Summer 1995). "Fascism and Silence: The Coded History of Amalia Popper". James Joyce Quarterly. 32 (3/4). University of Tulsa: 502–503. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ McCourt, John (Fall 2002). "Joycean Multimodalities: A Preliminary Investigation of Giacomo Joyce". Journal of Modern Literature. XXVI (1). Indiana University Press: 18. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Delville 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Delville 1998, p. 26.

Works Cited[edit]

- Henegar, Lucielle (1986). "Beating Swords into Ploughshares: Hereford Military Rservation and Reception Center". West Texas Historical Association Year Book. 62. ISSN 0886-6155.

- Keefer, Louis E. (1992). Italian Prisoners of War in America 1942-1946. New York: Praeger. ISBN 027593845X.

- Rogers, Joe D. (1989). "Camp Hereford: Italian Prisoners of War on the Texas Plains, 1942-1945". Panhandle-Plains Historical Review. 62: 57–110. ISSN 0148-7795.

- Williams, Donald Mace (1992). Interlude in Umbarger. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0896722767. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Hurt, R. Douglas (2008). The Great Plains during World War II. Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803224094. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- Graves, Debe (1982). "POW Camp". Deaf Smith County, Texas, 1876-1981 : the land and its people. Deaf Smith County, Texas: Deaf Smith County Historical Society. pp. 60–61. OCLC 748292802. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Walker, Richard Paul (May 1980). Prisoners of War in Texas During World War II (PDF) (PhD). North Texas State University. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Conquest, Robert (1972). Lenin. London: Fontana/Collins. ISBN 9780006326168. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Catlin, George (1842). Letters and Notes on the Customs and Manners of the North American Indians. Vol. 1 (4th ed.). New York: Wiley and Putnam. OCLC 2127425. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- Beal, Chandra Moira (1999). Splash Across Texas!. Austin, Texas: La Luna Publishing. ISBN 0-9671604-0-5.

- Swenson, Hannah (1 May 2002). USDI/NPS NRHP Registrafion Form Deep Eddy Bathing Beach, Austin, Travis County, Texas (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Vaughan, Hannah (2008). "Deep Eddy Bathhouse: Preserving a Sense of Place, One Layer at a Time". Sound Historian. 11: 14–23. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Beresford, David (1987). Ten men dead : the story of the 1981 Irish hunger strike. London: Grafton Books. ISBN 0586065334. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- English, Richard (2003). Armed struggle: the history of the IRA. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195166051. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- Feehan, John (1985). Bobby Sands and the tragedy of Northern Ireland. Sag Harbor, NY: Permanent Press. ISBN 0932966632. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- O'Hearn, Denis (2006). Nothing but an unfinished song : Bobby Sands, the Irish hunger striker who ignited a generation. New York: Nation Books. ISBN 9781560258421. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- Brunson III, James E. (2020). "Hotel Resorts and the Emergence of the Black Baseball Professional". In Peterson, Todd (ed.). The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 9781476665146.

- Peterson, Robert (1970). Only the ball was white. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780136372158. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Browne, Paul (Fall 2011). "You Can't Tell the Players". Black Ball. 4 (2). McFarland & Company, Inc. doi:10.3172/BLB.4.2.55. ISSN 1939-8484.

- Ellmann, Richard (1968). Introduction. Giacomo Joyce. By Joyce, James. London: Faber and Faber.

- Malloy, Jerry (2005). "The Birth of the Cuban Giants: The Origins of Black Professional Baseball". In Kirwin, Bill (ed.). Out of the Shadows. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803251533.

- Malloy, Jerry (1995). Introduction. Sol White's history of colored base ball, with other documents on the early Black game, 1886-1936. By White, Sol. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803247710. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- Lomax, Michael E. (2003). Black baseball entrepreneurs, 1860-1901. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815607865. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Harlow, Alvan F. (September 1938). "Unrecognized Stars". Esquire. X (3). Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- White, Sol (1995). Sol White's history of colored base ball, with other documents on the early Black game, 1886-1936. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803247710. Retrieved 20 January 2022.