User:Trevdna/Life of Joseph Smith

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

The life of Joseph Smith began in Sharon, Vermont in 1805, and ended in 1844 with a violent death by gunshot in the jail in Carthage, Illinois.

After Smith's birth, Smith moved with his family to the western region of New York State, following a series of crop failures in 1816. Living in an area of intense religious revivalism during the Second Great Awakening, Smith reported experiencing a series of visions. The first of these was in 1820, when he saw "two personages" (whom he eventually described as God the Father and Jesus Christ). In 1823, he said he was visited by an angel who directed him to a buried book of golden plates inscribed with a Judeo-Christian history of an ancient American civilization. In 1830, Smith published the Book of Mormon, which he described as an English translation of those plates. The same year he organized the Church of Christ, calling it a restoration of the early Christian Church. Members of the church were later called "Latter Day Saints" or "Mormons".

In 1831, Smith and his followers moved west, planning to build a communal Zion in the American heartland. They first gathered in Kirtland, Ohio, and established an outpost in Independence, Missouri, which was intended to be Zion's "center place". During the 1830s, Smith sent out missionaries, published revelations, and supervised construction of the Kirtland Temple. Because of the collapse of the church-sponsored Kirtland Safety Society, violent skirmishes with non-Mormon Missourians, and the Mormon extermination order, Smith and his followers established a new settlement at Nauvoo, Illinois, of which he was the spiritual and political leader. In 1844, when the Nauvoo Expositor criticized Smith's power and his practice of polygamy, Smith and the Nauvoo City Council ordered the destruction of its printing press, inflaming anti-Mormon sentiment. Fearing an invasion of Nauvoo, Smith rode to Carthage, Illinois, to stand trial, but was killed when a mob stormed the jailhouse.

Early years (1805–1827)[edit]

Joseph Smith was born on December 23, 1805, in Vermont, on the border between the villages of South Royalton and Sharon, to Lucy Mack Smith and her husband Joseph Smith Sr., a merchant and farmer.[1][a] He was one of eleven children. At the age of seven, Smith suffered a crippling bone infection and, after receiving surgery, used crutches for three years.[2] After an ill-fated business venture and three successive years of crop failures culminating in the 1816 Year Without a Summer, the Smith family left Vermont and moved to the western region of New York State,[3] and took out a mortgage on a 100-acre (40 ha) farm in the townships of Palmyra and Manchester.[4]

The region was a hotbed of religious enthusiasm during the Second Great Awakening.[5][6] Between 1817 and 1825, there were several camp meetings and revivals in the Palmyra area.[7] Smith's parents disagreed about religion, but the family was caught up in this excitement.[8] Smith later recounted that he had become interested in religion by age 12, and as a teenager, may have been sympathetic to Methodism.[9] With other family members, he also engaged in religious folk magic, a relatively common practice in that time and place.[10] Both his parents and his maternal grandfather reported having visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God.[11] Smith said that, although he had become concerned about the welfare of his soul, he was confused by the claims of competing religious denominations.[12]

Years later, Smith wrote that he had received a vision that resolved his religious confusion.[13] He said that in 1820, while he had been praying in a wooded area near his home, God the Father and Jesus Christ together appeared to him, told him his sins were forgiven, and said that all contemporary churches had "turned aside from the gospel."[14] Smith said he recounted the experience to a Methodist minister, who dismissed the story "with great contempt".[15] According to historian Steven C. Harper, "There is no evidence in the historical record that Joseph Smith told anyone but the minister of his vision for at least a decade", and Smith might have kept it private because of how uncomfortable that first dismissal was.[16] During the 1830s, Smith orally described the vision to some of his followers, though it was not widely published among Mormons until the 1840s.[17] This vision later grew in importance to Smith's followers, who eventually regarded it as the first event in the restoration of Christ's church to Earth.[18] Smith himself may have originally considered the vision to be a personal conversion.[19]

According to Smith's later accounts, while praying one night in 1823, he was visited by an angel named Moroni. Smith claimed this angel revealed the location of a buried book made of golden plates, as well as other artifacts including a breastplate and a set of interpreters composed of two seer stones set in a frame, which had been hidden in a hill near his home.[20] Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning, but was unsuccessful because Moroni returned and prevented him.[21] He reported that during the next four years he made annual visits to the hill, but, until the fourth and final visit, each time he returned without the plates.[22]

Meanwhile, Smith's family faced financial hardship, due in part to the death of his oldest brother Alvin, who had assumed a leadership role in the family.[23] Family members supplemented their meager farm income by hiring out for odd jobs and working as treasure seekers,[24] a type of magical supernaturalism common during the period.[25] Smith was said to have an ability to locate lost items by looking into a seer stone, which he also used in treasure hunting, including, beginning in 1825, several unsuccessful attempts to find buried treasure sponsored by Josiah Stowell, a wealthy farmer in Chenango County.[26] In 1826, Smith was brought before a Chenango County court for "glass-looking", or pretending to find lost treasure; Stowell's relatives accused Smith of tricking Stowell and faking an ability to perceive hidden treasure, though Stowell attested that he believed Smith had such abilities.[27][b] The result of the proceeding remains unclear because primary sources report conflicting outcomes.[c]

While boarding at the Hale house, located in the township of Harmony (now Oakland) in Pennsylvania, Smith met and courted Emma Hale. When he proposed marriage, her father, Isaac Hale, objected; he believed Smith had no means to support his daughter.[28] Hale also considered Smith a stranger who appeared "careless" and "not very well educated."[29] Smith and Emma eloped and married on January 18, 1827, after which the couple began boarding with Smith's parents in Manchester. Later that year, when Smith promised to abandon treasure seeking, his father-in-law offered to let the couple live on his property in Harmony and help Smith get started in business.[30]

Smith made his last visit to the hill shortly after midnight on September 22, 1827, taking Emma with him.[31] This time, he said he successfully retrieved the plates.[32] Smith said Moroni commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else, but to translate them and publish their translation. He also said the plates were a religious record of Middle-Eastern indigenous Americans and were engraved in an unknown language, called reformed Egyptian.[33] He told associates that he was capable of reading and translating them.[34]

Although Smith had abandoned treasure hunting, former associates believed he had double crossed them and had taken the golden plates for himself, property they believed should be jointly shared.[35] After they ransacked places where they believed the plates might have been hidden, Smith decided to leave Palmyra.[36]

Founding a church (1827–1830)[edit]

In October 1827, Smith and Emma permanently moved to Harmony, aided by a relatively prosperous neighbor, Martin Harris.[37] Living near his in-laws, Smith transcribed some characters that he said were engraved on the plates and dictated their translations to Emma.[38]

In February 1828, after visiting Smith in Harmony, Harris took a sample of the characters Smith had copied to a few prominent scholars, including Charles Anthon.[39] He said Anthon initially authenticated the characters and their translation, but then retracted his opinion after learning that Smith claimed to have received the plates from an angel.[40] Anthon denied Harris's account of the meeting, claiming instead that he had tried to convince Harris that he was the victim of a fraud.[41] In any event, Harris returned to Harmony in April 1828 and began serving as Smith's scribe.[42]

Although Harris and his wife Lucy were early supporters of Smith, by June 1828 they began to have doubts about the existence of the golden plates. Harris persuaded Smith to let him take 116 pages of manuscript to Palmyra to show a few family members, including his wife.[43] While in Harris's possession, the manuscript—of which there was no other copy—was lost.[d] Smith was devastated by this loss, especially since it came at the same time as he lost his first son, who died shortly after birth.[44] Smith said that as punishment for his having lost the manuscript, Moroni returned, took away the plates, and revoked his ability to translate.[45] During this period, Smith briefly attended Methodist meetings with his wife, until a cousin of hers objected to inclusion of a "practicing necromancer" on the Methodist class roll.[46]

Smith said that Moroni returned the plates to him in September 1828,[47] and he then dictated some of the book to his wife Emma.[48][e] In April 1829 he met Oliver Cowdery, who had also dabbled in folk magic; and with Cowdery as scribe, Smith began a period of "rapid-fire translation".[49][f] Between April and early June 1829, the two worked full time on the manuscript, then moved to Fayette, New York, where they continued the work at the home of Cowdery's friend, Peter Whitmer.[50] When the narrative described an institutional church and a requirement for baptism, Smith and Cowdery baptized each other.[51] Dictation was completed about July 1, 1829.[52]

Although Smith had previously refused to show the plates to anyone, he told Harris, Cowdery, and Whitmer's son David that they would be allowed to see them.[53] These men, known collectively as the Three Witnesses, signed a statement stating that they had been shown the golden plates by an angel, and that the voice of God had confirmed the truth of their translation. Later, a group of Eight Witnesses — composed of male members of the Whitmer and Smith families – issued a statement that they had been shown the golden plates by Smith.[54] According to Smith, Moroni took back the plates once Smith finished using them.[55]

The completed work, titled the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra by printer Egbert Bratt Grandin[56] and was first advertised for sale on March 26, 1830.[57] Less than two weeks later, on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ, and small branches were established in Manchester, Fayette, and Colesville, New York.[58] The Book of Mormon brought Smith regional notoriety and renewed the hostility of those who remembered the 1826 Chenango County trial.[59] After Cowdery baptized several new church members, Smith's followers were threatened with mob violence. Before Smith could confirm the newly baptized, he was arrested and charged with being a "disorderly person."[60] Although he was acquitted, both he and Cowdery fled to Colesville to escape a gathering mob. Smith later claimed that, probably around this time, Peter, James, and John had appeared to him and had ordained him and Cowdery to a higher priesthood.[61]

Smith's authority was undermined when Cowdery, Hiram Page, and other church members also claimed to receive revelations.[62] In response, Smith dictated a revelation which clarified his office as a prophet and an apostle, stating that only he had the ability to declare doctrine and scripture for the church.[63] Smith then dispatched Cowdery, Peter Whitmer, and others on a mission to proselytize Native Americans.[64] Cowdery was also assigned the task of locating the site of the New Jerusalem, which was to be "on the borders" of the United States with what was then Indian territory.[65]

On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's party passed through northeastern Ohio, where Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred followers of his variety of Campbellite Restorationism converted to the Church of Christ, swelling the ranks of the new organization dramatically.[66] After Rigdon visited New York, he soon became Smith's primary assistant.[67] With growing opposition in New York, Smith announced a revelation that his followers should gather to Kirtland, Ohio, establish themselves as a people and await word from Cowdery's mission.[68]

Life in Ohio (1831–1838)[edit]

When Smith moved to Kirtland in January 1831, he encountered a religious culture that included enthusiastic demonstrations of spiritual gifts, including fits and trances, rolling on the ground, and speaking in tongues.[69] Rigdon's followers were practicing a form of communalism. Smith brought the Kirtland congregation under his authority and tamed ecstatic outbursts.[70] He had promised church elders that in Kirtland they would receive an endowment of heavenly power, and at the June 1831 general conference, he introduced the greater authority of a High ("Melchizedek") Priesthood to the church hierarchy.[71]

Converts poured into Kirtland. By the summer of 1835, there were fifteen hundred to two thousand Latter Day Saints in the vicinity,[72] many expecting Smith to lead them shortly to the Millennial kingdom.[73] Though his mission to the Native Americans had been a failure,[74][g] Cowdery and the other missionaries with him were charged with finding a site for "a holy city". They found Jackson County, Missouri. After Smith visited in July 1831, he pronounced the frontier hamlet of Independence the "center place" of Zion.[75]

For most of the 1830s, the church was effectively based in Ohio.[76] Smith lived there, though he visited Missouri again in early 1832 to prevent a rebellion of prominent church members who believed the church in Missouri was being neglected.[77] Smith's trip was hastened by a mob of Ohio residents who were incensed over the church's presence and Smith's political power. The mob beat Smith and Rigdon unconscious, tarred and feathered them, and left them for dead.[78]

In Jackson County, existing Missouri residents resented the Latter Day Saint newcomers for both political and religious reasons.[h] Tension increased until July 1833, when non-Mormons forcibly evicted the Mormons and destroyed their property. Smith advised his followers to bear the violence patiently until after they had been attacked multiple times, after which they could fight back.[79][i] Armed bands exchanged fire, killing one Mormon and two non-Mormons, until the old settlers forcibly expelled the Latter Day Saints from the county.[80]

In response, Smith led a small paramilitary expedition, called Zion's Camp, to aid the Latter Day Saints in Missouri.[81] As a military endeavor, the expedition was a failure. The men of the expedition were disorganized, suffered from a cholera outbreak and were severely outnumbered. Smith sent two church representatives to petition Missouri governor Daniel Dunklin for protection and support, but Dunklin declined to aid the Mormons. By the end of June, Smith deescalated the confrontation, sought peace with Jackson County's residents, and disbanded Zion's Camp.[82] Nevertheless, Zion's Camp transformed Latter Day Saint leadership because many future church leaders came from among the participants.[83]

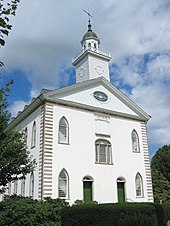

After the Camp returned to Ohio, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish various governing bodies in the church.[84] He gave a revelation announcing that in order to redeem Zion, his followers would have to receive an endowment in the Kirtland Temple.[85] In March 1836, at the temple's dedication, many who received the endowment reported seeing visions of angels and engaged in prophesying and speaking in tongues.[j][86]

In January 1837, Smith and other churchleaders created a joint stock company, called the Kirtland Safety Society (KSS), to act as a quasi-bank; the company issued banknotes partly capitalized by real estate. Smith encouraged his followers to buy the notes, in which he invested heavily himself. The bank failed within a month.[87] As a result, Latter Day Saints in Kirtland suffered extreme high volatility and intense pressure from debt collectors. Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church, including many of Smith's closest advisers.[88]

The failure of the bank was but one part a series of internal disputes led to the demise of the Kirtland community.[89] Cowdery, who by then was Assistant President of the Church,[90] had accused Smith of engaging in a sexual relationship with a teenage servant in his home, Fanny Alger.[91] Construction of the Kirtland Temple had only added to the church's debt, and Smith was hounded by creditors.[92] Having heard of a large sum of money supposedly hidden in Salem, Massachusetts, he traveled there and announced a revelation that God had "much treasure in this city".[93] After a month, however, he returned to Kirtland empty-handed.[94] After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of banking fraud, he and Rigdon fled for Missouri in January 1838.[95]

Life in Missouri (1838–39)[edit]

By 1838, Smith had abandoned plans to redeem Zion in Jackson County, and instead declared the town of Far West, Missouri, in Caldwell County, as the new "Zion".[96][k] In Missouri, the church also took the name "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints", and construction began on a new temple.[97] In the weeks and months after Smith and Rigdon arrived at Far West, thousands of Latter Day Saints followed them from Kirtland.[98] Smith encouraged the settlement of land outside Caldwell County, instituting a settlement in Adam-ondi-Ahman, in Daviess County.[99]

During this time, a church council expelled many of the oldest and most prominent leaders of the church—including Cowdery, John Whitmer, David Whitmer, and W. W. Phelps—on allegations of misusing church property and finance amid tense relations between them and Smith.[100] Smith explicitly approved of the excommunication of these men, who were known collectively as the "dissenters".[101]

Political and religious differences between old Missourians and newly arriving Latter Day Saint settlers provoked tensions between the two groups, much as they had in Jackson County. By this time, Smith's experiences with mob violence led him to believe that his faith's survival required greater militancy against anti-Mormons.[102] Around June 1838, Sampson Avard formed a covert organization called the Danites to intimidate Latter Day Saint dissenters and oppose anti-Mormon militia units.[103] Though it is unclear how much Smith knew of the Danites' activities, he clearly approved of those of which he did know.[104] After Rigdon delivered a sermon that implied dissenters had no place in the Latter Day Saint community, the Danites forcibly expelled them from the county.[105]

In a speech given at Far West’s Fourth of July celebration, Rigdon declared that Mormons would no longer tolerate persecution by the Missourians and spoke of a "war of extermination" if Mormons were attacked.[106] Smith implicitly endorsed this speech,[107] and many non-Mormons understood it to be a thinly veiled threat. They unleashed a flood of anti-Mormon rhetoric in newspapers and in stump speeches given during the 1838 election campaign.[108]

On August 6, 1838, non-Mormons in Gallatin, Missouri, tried to prevent Mormons from voting,[109] and the election day scuffles initiated the 1838 Mormon War. Non-Mormon vigilantes raided and burned Mormon farms, while Danites and other Mormons pillaged non-Mormon towns.[110] In the Battle of Crooked River, a group of Mormons attacked the Missouri state militia, mistakenly believing them to be anti-Mormon vigilantes. Governor Lilburn Boggs then ordered that the Mormons be "exterminated or driven from the state".[111] On October 30, a party of Missourians surprised and killed seventeen Mormons in the Haun's Mill massacre.[112]

The following day, the Mormons surrendered to 2,500 state troops and agreed to forfeit their property and leave the state.[113] Smith was immediately brought before a military court, accused of treason, and sentenced to be executed the next morning, but Alexander Doniphan, who was Smith's former attorney and a brigadier general in the Missouri militia, refused to carry out the order.[114] Smith was then sent to a state court for a preliminary hearing, where several of his former allies testified against him.[115] Smith and five others, including Rigdon, were charged with treason, and transferred to the jail at Liberty, Missouri, to await trial.[116]

Smith's months in prison with an ill and complaining Rigdon strained their relationship. Meanwhile, Brigham Young–as president of the church's Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, one of the church's governing bodies–rose to prominence when he organized the move of about 14,000 Mormon refugees to Illinois and eastern Iowa.[117]

Smith bore his imprisonment stoically. Understanding that he was effectively on trial before his own people, many of whom considered him a fallen prophet, he wrote a personal defense and an apology for the activities of the Danites. "The keys of the kingdom", he wrote, "have not been taken away from us".[118] Though he directed his followers to collect and publish their stories of persecution, he also urged them to moderate their antagonism toward non-Mormons.[119] On April 6, 1839, after a grand jury hearing in Daviess County, Smith and his companions escaped custody, almost certainly with the connivance of the sheriff and guards.[120]

Life in Nauvoo, Illinois (1839–1844)[edit]

Many American newspapers criticized Missouri for the Haun's Mill massacre and the state's expulsion of the Mormons.[121] Illinois then accepted Mormon refugees who gathered along the banks of the Mississippi River,[122] where Smith purchased high-priced, swampy woodland in the hamlet of Commerce.[123] He attempted to portray the Mormons as an oppressed minority and unsuccessfully petitioned the federal government for help in obtaining reparations.[124] During the summer of 1839, while Mormons in Nauvoo suffered from a malaria epidemic, Smith sent Young and other apostles to missions in Europe, where they made numerous converts, many of them poor factory workers.[125]

Smith also attracted a few wealthy and influential converts, including John C. Bennett, the Illinois quartermaster general.[126] Bennett used his connections in the Illinois state legislature to obtain an unusually liberal charter for the new city, which Smith renamed "Nauvoo" (Hebrew נָאווּ, meaning "to be beautiful").[127] The charter granted the city virtual autonomy, authorized a university, and granted Nauvoo habeas corpus power—which allowed Smith to fend off extradition to Missouri.[l] Though Latter Day Saint authorities controlled Nauvoo's civil government, the city guaranteed religious freedom for its residents.[128] The charter also authorized the Nauvoo Legion, a militia whose actions were limited only by state and federal constitutions. Smith and Bennett became its commanders, and were styled Lieutenant General and Major General respectively. As such, they controlled by far the largest body of armed men in Illinois.[129] Smith appointed Bennett as Assistant President of the Church, and Bennett was elected Nauvoo's first mayor.[130]

The early Nauvoo years were a period of doctrinal innovation. Smith introduced baptism for the dead in 1840, and in 1841 construction began on the Nauvoo Temple as a place for recovering lost ancient knowledge.[131] An 1841 revelation promised the restoration of the "fullness of the priesthood"; and in May 1842, Smith inaugurated a revised endowment or "first anointing".[132] The endowment resembled the rites of Freemasonry that Smith had observed two months earlier when he had been initiated "at sight" into the Nauvoo Masonic lodge.[133] At first, the endowment was open only to men, who were initiated into a special group called the Anointed Quorum. For women, Smith introduced the Relief Society, a service club and sorority within which Smith predicted women would receive "the keys of the kingdom".[134] Smith also elaborated on his plan for a Millennial kingdom; no longer envisioning the building of Zion in Nauvoo, he viewed Zion as encompassing all of North and South America, with Mormon settlements being "stakes" of Zion's metaphorical tent.[135] Zion also became less a refuge from an impending tribulation than a great building project.[136] In the summer of 1842, Smith revealed a plan to establish the millennial Kingdom of God, which would eventually establish theocratic rule over the whole Earth.[137]

It was around this time that Smith began secretly marrying additional wives, a practice called plural marriage.[138] He introduced the doctrine to a few of his closest associates, including Bennett, who used it as an excuse to seduce numerous women, wed and unwed.[139][m] When rumors of polygamy (called "spiritual wifery" by Bennett) got abroad, Smith forced Bennett's resignation as Nauvoo mayor. In retaliation, Bennett left Nauvoo and began publishing sensational accusations against Smith and his followers.[140]

By mid-1842, popular opinion in Illinois had turned against the Mormons. After an unknown assailant shot and wounded Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs in May 1842, anti-Mormons circulated rumors that Smith's bodyguard, Porter Rockwell, was the gunman.[141] Though the evidence was circumstantial, Boggs ordered Smith's extradition. Certain he would be killed if he ever returned to Missouri, Smith went into hiding twice during the next five months, until the U.S. Attorney for Illinois argued that his extradition would be unconstitutional.[142] (Rockwell was later tried and acquitted.) In June 1843, enemies of Smith convinced a reluctant Illinois Governor Thomas Ford to extradite Smith to Missouri on an old charge of treason. Two law officers arrested Smith but were intercepted by a party of Mormons before they could reach Missouri. Smith was then released on a writ of habeas corpus from the Nauvoo municipal court.[143] While this ended the Missourians' attempts at extradition, it caused significant political fallout in Illinois.[144]

In December 1843, Smith petitioned Congress to make Nauvoo an independent territory with the right to call out federal troops in its defense.[146] Smith then wrote to the leading presidential candidates, asking what they would do to protect the Mormons. After receiving noncommittal or negative responses, he announced his own independent candidacy for president of the United States, suspended regular proselytizing, and sent out the Quorum of the Twelve and hundreds of other political missionaries.[147] In March 1844 – following a dispute with a federal bureaucrat – he organized the secret Council of Fifty, which was given the authority to decide which national or state laws Mormons should obey, as well as establish its own government for Mormons.[148] Before his death the Council also voted unanimously to elect Smith "Prophet, Priest, and King."[149] The Council was likewise appointed to select a site for a large Mormon settlement in the Republic of Texas, Oregon, or California (then controlled by Mexico), where Mormons could live under theocratic law beyond the control of other governments.[150]

Death[edit]

By early 1844, a rift developed between Smith and a half dozen of his closest associates.[151] Most notably, William Law, his trusted counselor, and Robert Foster, a general of the Nauvoo Legion, disagreed with Smith about how to manage Nauvoo's economy.[152] Both also said that Smith had proposed marriage to their wives.[153] Believing these men were plotting against his life, Smith excommunicated them on April 18, 1844.[154] Law and Foster subsequently formed a competing "reform church", and in the following month, at the county seat in Carthage, they procured indictments against Smith for perjury (as Smith publicly denied having more than one wife) and polygamy.[155]

On June 7, the dissidents published the first (and only) issue of the Nauvoo Expositor, calling for reform within the church but also appealing politically to non-Mormons.[156] The paper decried Smith's new "doctrines of many Gods", alluded to his theocratic aspirations, and called for a repeal of the Nauvoo city charter.[o] It also attacked Smith's practice of polygamy, implying that he was using religion as a pretext to draw unassuming women to Nauvoo to seduce and marry them.[157]

Fearing the Expositor would provoke a new round of violence against the Mormons, the Nauvoo city council declared the newspaper a public nuisance and ordered the Nauvoo Legion to destroy its printing press.[158] During the council debate, Smith vigorously urged the council to order the press destroyed,[159] not realizing that destroying a newspaper was more likely to incite an attack than any of the newspaper's accusations.[160]

Destruction of the newspaper provoked a strident call to arms from Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal and longtime critic of Smith.[162] Fearing mob violence, Smith mobilized the Nauvoo Legion on June 18 and declared martial law.[163] Officials in Carthage responded by mobilizing a small detachment of the state militia, and Governor Ford intervened, threatening to raise a larger militia unless Smith and the Nauvoo city council surrendered themselves.[164] Smith initially fled across the Mississippi River, but shortly returned and surrendered to Ford.[165] On June 25, Smith and his brother Hyrum arrived in Carthage to stand trial for inciting a riot.[166] Once the Smiths were in custody, the charges were increased to treason, preventing them from posting bail.[167] John Taylor and Willard Richards voluntarily accompanied the Smiths in Carthage Jail.[168]

On June 27, 1844, an armed mob with blackened faces stormed Carthage Jail, where Joseph and Hyrum were being detained. Hyrum, who was trying to secure the door, was killed instantly with a shot to the face. Smith fired three shots from a pepper-box pistol that his friend, Cyrus H. Wheelock, had lent him, wounding three men,[169] before he sprang for the window.[170][p] He was shot multiple times before falling out the window, crying, "Oh Lord my God!" He died shortly after hitting the ground, but was shot several more times by an improvised firing squad before the mob dispersed.[171] Five men were tried for Smith's murder, but all were acquitted.[172]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Modern DNA testing of Smith's relatives suggests that his family were of Irish descent. Perego, Ugo A.; Myres, Natalie M.; Woodward, Scott R. (2005). "Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications". Journal of Mormon History. 31 (2): 42–60. JSTOR 23289931.; De Groote, Michael (August 8, 2008). "DNA shows Joseph Smith was Irish". Deseret News. Retrieved July 2, 2018.; "Joseph Smith DNA Revealed: New Clues from the Prophet's Genes – FairMormon". FairMormon. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Butler, Benjamin Franklin; Spencer, John Canfield (1829). Revised Statutes of the State of New York. Vol. 1. Albany, NY: Packard and Van Benthuysen. p. 638: part I, title 5, § 1. (According to New York law at the time "[A]ll persons pretending to tell fortunes, or where lost or stolen goods may be found, ... shall be deemed disorderly persons."); According to Bushman (2008, p. 22), this practice was "an illegal activity in New York because it was often practiced by swindlers".

- ^ Jortner (2022, p. 33) summarizes, "It is unclear what happened next." For a survey of the primary sources, see Vogel, Dan. "Rethinking the 1826 Judicial Decision". Mormon Scripture Studies: An e-Journal of Critical Thought. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. See also "Introduction to State of New York v. JS–A". The Joseph Smith Papers. Archived from the original on December 20, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2022, which includes a calendar of documents and likewise concludes that "the lack of verifiable contemporary records renders tentative any conclusion about the case's outcome."

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 16) identifies the manuscript Harris lost as having been "the only existing copy". The Harrises initially kept the manuscript locked in Lucy Harris's bureau drawers. When Martin Harris wanted to show the pages to a friend while Lucy was absent, he broke the lock and moved the manuscript to his own drawers. The Harrises "later discovered the manuscript was missing", presumably stolen by an unidentified party; see Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, pp. 117–118).

- ^ For a tentative view that Smith may have dictated significant portions of the book of Mosiah to Emma Smith's and Samuel Smith's scribing, see p. 27 in Jensen, Robin Scott (2022). "The Authenticity of the Chicago Leaves of the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: A Fragmented Approach". Journal of Book of Mormon Studies. 31: 1–30. doi:10.14321/23744774.37.01 (inactive February 24, 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2023 (link) - ^ Bushman (2005, p. 74) states that Smith and Cowdery began dictation where the narrative left off after the lost 116 pages, in a location now representing the Book of Mosiah. A revelation would later direct them not to re-translate the lost text, to ensure that the lost pages could not later be found and compared to the re-translation. Bushman (2005, p. 71) states Cowdery was a school teacher who had previously boarded with the Smith family. Bushman (2005, p. 73). See also Quinn (1998, pp. 35–36, 121).

- ^ Per Bushman (2005, p. 161), Richard W. Cummins, a government liaison to the Shawnee and Delaware tribes, issued an order to desist because the missionaries had not received official permission to meet with and proselytize the tribes under his authority.

- ^ These reasons included the settlers' understanding that the Mormons intended to appropriate their property and establish a Millennial political kingdom (Remini (2002, pp. 114)), their friendliness with the Indians (Remini (2002, pp. 114–15); Arrington & Bitton (1979, p. 61)), their perceived religious blasphemy Remini (2002, p. 114), and especially the belief that they were abolitionists (Remini (2002, pp. 113–14)). Additionally, their rapid growth aroused fears that they would soon constitute a majority in local elections, and thus "rule the county." Bushman (2005, p. 222).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 82–83) explains: Smith’s August 1833 revelation said that after a fourth attack, "the [Latter Day] Saints were "justified" by God in violence against any attack by any enemy "until they had avenged themselves on all their enemies to the third and fourth generation", citing Smith et al. (1835, p. 218)).

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 116) also notes that "the ultimate cost [of the temple] came to approximately $50,000, an enormous sum for a people struggling to stay alive."

- ^ In an attempt to address the crisis caused by the Mormon expulsion from Jackson County, the Missouri state legislature "informally designed" Caldwell County "to accommodate Mormons"; see p. 23 in Walker, Jeffrey N. (2008). "Mormon Land Rights in Caldwell and Daviess Counties and the Mormon Conflict of 1838: New Findings and New Understandings". BYU Studies. 47 (1): 4–55. JSTOR 43044611 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Prior to the charter, Smith had narrowly avoided two extradition attempts. See Quinn (1994, p. 110); Brodie (1971, pp. 272–273); Bushman (2005, pp. 425–426).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 311–12) also explains that Bennett, a minimally trained doctor, also promised abortions to any who might become pregnant.

- ^ There is disagreement among historians about the identification and provenance of this daguerrotype; for an overview of arguments and positions for and against, see Stack, Peggy Fletcher (July 29, 2022). "'The Whole Affect Feels Off to Me' — Why Some Historians Doubt That's a Photo of Joseph Smith". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ Smith had recently given his King Follett discourse, in which he taught that God was once a man, and that men and women could become gods. Bushman (2005, p. 539); Brodie (1971, pp. 375); Marquardt (1999, p. 312); Quinn (1994, p. 139) notes that the publishers "intended to emphasize the details of Smith's 'delectable plan of government'" in a subsequent edition which was planned but never produced; Ulrich (2017, pp. 113–114) explains that statements in the Expositor "were powerful because they were simple, straightforward, and true" and that they accompanied content which "fanned a fury that soon exploded into violence".

- ^ Smith and his companions were staying in the jailer's bedroom, which did not have bars on the windows.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 9, 30); Smith (1832, p. 1)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 21)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 27–32)

- ^ "Smith Family Log Home, Palmyra, New York". Ensign Peak Foundation. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Martin, John H. (2005). "An Overview of the Burned-Over District". Saints, Sinners and Reformers: The Burned-Over District Re-Visited, published in the Crooked Lake Review. No. 137. Fall 2005.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:7was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 36–37); Quinn (1998, p. 136)

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. xx); Hill (1989, pp. 10–11); Brooke (1994, p. 129)

- ^ Vogel (2004, pp. 26–7); D. Michael Quinn (July 12, 2006). "Joseph Smith's Experience of a Methodist 'Camp-Meeting' in 1820" (PDF). Dialogue Paperless. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 30–31); Bushman (2005, p. 51); Shipps (1985, pp. 7–8); Remini (2002, pp. 16, 33); Hill (1977, p. 53)

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 14–16, 137); Bushman (2005, pp. 26, 36); Brooke (1994, pp. 150–51); Mack (1811, p. 25); Smith (1853, pp. 54–59, 70–74)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 38–9); Vogel (2004, p. 30); Quinn (1998, p. 136); Remini (2002, p. 37)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 39); Vogel (2004, p. 30); Quinn (1998, p. 136)

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 37–38); Bushman (2005, p. 39); Vogel (2004, p. 30)

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. 30); Remini (2002, p. 40); Harper (2019, p. 9)

- ^ Harper (2019, pp. 10–12)

- ^ Harper (2019, pp. 1, 51–55)

- ^ Allen, James B. (Autumn 1966). "The Significance of Joseph Smith's "First Vision" in Mormon Thought". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 1 (3): 29–46. doi:10.2307/45223817. JSTOR 45223817. S2CID 222223353.

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 39); Vogel (2004, p. 30); Remini (2002, p. 39)

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 136–38); Bushman (2005, p. 43); Shipps (1985, pp. 151–152)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 50); Jortner (2022, p. 38)

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 163–64); Bushman (2005, p. 54)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 42)

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 21); Bushman (2005, pp. 33, 48)

- ^ Taylor, Alan (Spring 1986). "The Early Republic's Supernatural Economy: Treasure Seeking in the American Northeast, 1780–1830". American Quarterly. 38 (1): 6–34. doi:10.2307/2712591. JSTOR 2712591.

- ^ Newell & Avery (1994, pp. 17); Brooke (1994, pp. 152–53); Quinn (1998, pp. 43–44, 54–57); , Persuitte (2000, pp. 33–53); Bushman (2005, pp. 45–53); Jortner (2022, p. 29)

- ^ Jortner (2022, pp. 29–31)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 53); Vogel (2004, p. 89); Quinn (1998, p. 164)

- ^ Newell & Avery (1994, pp. 17–18)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 53–54)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 12); Quinn (1998, pp. 163–64); Bushman (2005, pp. 54, 59); Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, p. 126)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 59–60); Shipps (1985, p. 153)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 9); Bushman (2005, p. 54); Howe (2007, pp. 313–314); Jortner (2022, p. 41)

- ^ Bushman (2004, pp. 238–242); Howe (2007, p. 313)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 61); Howe (2007, p. 315); Jortner (2022, pp. 36–38)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 12); Remini (2002, p. 55); Bushman (2005, pp. 60–61)

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 55–56); Newell & Avery (1994, p. 2); Bushman (2005, pp. 62–63)

- ^ Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, p. 133); Bushman (2005, p. 63); Remini (2002, p. 56)

- ^ Shipps (1985, pp. 15, 153); Bushman (2005, p. 63)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 63–66); Remini (2002, pp. 57–58)

- ^ Howe (1834, pp. 269–72) (Anthon's description of his meeting with Harris). But see Vogel (2004, p. 115) (arguing that Anthon's initial assessment was likely more positive than he would later admit).

- ^ Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, p. 129)

- ^ Shipps (1985, pp. 15–16); Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, pp. 117–119); Smith (1853, pp. 117–18)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 67–68)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 17)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 68–70)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 18); Bushman (2005, pp. 70, 578n46); Phelps (1833, sec. 2:4–5); Smith (1853, p. 126)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 70)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 70)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 70–74)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 5–6, 15–20); Bushman (2005, pp. 74–75)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 78)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 77)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 77–79)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 68)

- ^ Jortner (2022, p. 43)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 154)

- ^ For the April 6 establishment of a church organization, see Shipps (1985, p. 154); for Fayette and Manchester (and some ambiguity over a Palmyra presence), see Hill (1989, pp. 27, 201n84); for the Colesville congregation, see Jortner (2022, p. 57);

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 117); Vogel (2004, pp. 484–486, 510–512)

- ^ Hill (1989, p. 28); Bushman (2005, pp. 116–18)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 24–26); Bushman (2005, p. 118)

- ^ Hill (1989, p. 27); Bushman (2005, p. 120)

- ^ Hill (1989, pp. 27–28); Bushman (2005, p. 121); Phelps (1833, p. 67)

- ^ Hill (1989, p. 28); Bushman (2005, p. 112); Jortner (2022, pp. 59–60, 93, 95)

- ^ Phelps (1833, p. 68); Bushman (2005, p. 122)

- ^ Parley Pratt said that the Mormon mission baptized 127 within two or three weeks "and this number soon increased to one thousand". See McKiernan, F. Mark (Summer 1970). "The Conversion of Sidney Rigdon to Mormonism". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 5 (2): 71–78. doi:10.2307/45224203. JSTOR 45224203. S2CID 254399092; Bushman (2005, p. 124); Jortner (2022, pp. 60–61)

- ^ McKiernan, F. Mark (Summer 1970). "The Conversion of Sidney Rigdon to Mormonism". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 5 (2): 71–78. doi:10.2307/45224203. JSTOR 45224203. S2CID 254399092

- Bushman (2005, p. 124)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 124–25); Howe (2007, p. 315)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 150–52); Remini (2002, p. 95)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 154–55); Hill (1977, p. 131)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 31–32); Bushman (2005, pp. 125, 156–60)

- ^ Arrington & Bitton (1979, p. 21)

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 81)

- ^ Turner (2012, p. 41)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 162–163); Smith et al. (1835, p. 154)

- ^ Arrington & Bitton (1979, p. 21)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 180–182)

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 109–10); Bushman (2005, pp. 178–80)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 181–83, 235)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 83–84); Bushman (2005, pp. 222–27)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 115)

- ^ Hill (1989, pp. 44–46) (for the petition to Dunklin and his declination as well as Smith deescalating and disbanding the camp); Bushman (2005, pp. 235–46) (for the numerical limitations, social tension, and cholera outbreak in the camp).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 246–247); Quinn (1994, p. 85)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 247); see also Remini (2002, pp. 100–104) for a timeline of Smith introducing the new organizational entities.

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 156–57); Smith et al. (1835, p. 233); Prince (1995, p. 32 & n.104).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 310–19)

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 122–123); Bushman (2005, pp. 328–334)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 124); Bushman (2005, pp. 331–32, 336–39)

- ^ Brooke (1994, p. 221)

- ^ Cluff, Randall (February 2000). Cowdery, Oliver (1806–1850), Mormon leader. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0802307.

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 322); Compton1997, pp. 25–42)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 217, 329)

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 261–64); Bushman (2005, p. 328)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 328–329)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 125); Bushman (2005, pp. 339–40); Hill (1977, p. 216)

- ^ Hill (1977, pp. 181–82); Bushman (2005, pp. 345, 384)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 210, 222–23); Quinn (1994, p. 628); Remini (2002, p. 131)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 125); Bushman (2005, pp. 341–46)

- ^ Walker, Jeffrey N. (2008). "Mormon Land Rights in Caldwell and Daviess Counties and the Mormon Conflict of 1838: New Findings and New Understandings". BYU Studies. 47 (1): 4–55. JSTOR 43044611 – via JSTOR; LeSueur, Stephen C. (Fall 2005). "Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons". Journal of Mormon History. 31 (2): 113–144. JSTOR 23289934 – via JSTOR

- ^ Marquardt (2005, p. 463) ; Remini (2002, p. 128); Quinn (1994, p. 93); Bushman (2005, pp. 324, 346–348)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 347–48)

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 92); Brodie (1971, p. 213); Bushman (2005, p. 355)

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 93); Remini (2002, p. 129)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 346–52); Quinn (1994, p. 93); Hill (1977, p. 225)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 94–95)

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 131–33)

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 96); Bushman (2005, p. 355)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 133)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 357)

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 134); Quinn (1994, pp. 96–99, 101); Bushman (2005, p. 363)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 364–65); Quinn (1994, p. 100)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 365–66); Quinn (1994, p. 97)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 366–67); Brodie (1971, p. 239)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 242, 344, 367); Brodie (1971, p. 241)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 369); Brodie (1971, pp. 225–26, 243–45)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 369–70)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 245–51); Bushman (2005, pp. 375–77))

- ^ Remini (2002, pp. 136–37); Brodie (1971, pp. 245–46);Quinn (1998, pp. 101–02)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 377–78)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 375); Brodie (1971, pp. 253–55); Bushman (2005, pp. 382, 635–36); Bentley, Joseph I. (1992). "Smith, Joseph: Legal Trials of Joseph Smith". In Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 1346–1348. ISBN 0-02-879602-0. OCLC 24502140. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 246–47, 259); Bushman (2005, p. 398)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 381)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 383–4)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 392–94, 398–99); Brodie (1971, pp. 259–60)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 386, 409); Brodie (1971, pp. 258, 264–65)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 410–11)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 267–68); Bushman (2005, p. 412,415)

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 106–08)

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 271)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 410–411)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 448–49); Park (2020, pp. 57–61)

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 113)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 449); Quinn (1994, pp. 114–15)

- ^ Quinn (1994, p. 634)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 384,404)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 415)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 111–12)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 427–28)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 460)

- ^ Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 12); Bushman (2005, pp. 461–62); Brodie (1971, p. 314)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 468); Brodie (1971, p. 323); Quinn (1994, p. 113)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 468–75)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 504–08)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 508)

- ^ Romig, Ronald; Mackay, Lachlan (Spring–Summer 2022). "Hidden Things Shall Come to Light: The Visual Image of Joseph Smith Jr". John Whitmer Historical Association Journal. 42 (1): 28–60. ISSN 0739-7852.

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 356); Quinn (1994, pp. 115–116)

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 118–19); Bushman (2005, pp. 514–15); Brodie (1971, pp. 362–64)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 519); Quinn (1994, pp. 120–22)

- ^ "How Joseph Smith and the Early Mormons Challenged American Democracy". The New Yorker. 2020-03-20. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 517)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 527–28)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 368–9); Quinn (1994, p. 528)

- ^ Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 14); Brodie (1971, pp. 369–371); Van Wagoner (1992, p. 39); Bushman (2005, pp. 660–61)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 549, 531)

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 373); Bushman (2005, pp. 531, 538); Park (2020, p. 227)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 539); Brodie (1971, pp. 374); Quinn (1994, p. 138)

- ^ Oaks & Hill (1975, p. 14); Davenport (2022, pp. 147–148). The text of the Nauvoo Expositor is available on Wikisource.

- ^ Park (2020, pp. 228–230); Marquardt (1999, p. 312)

- ^ Park (2020, pp. 229–230)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 541)

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 394)

- ^ Ulrich (2017, p. 114); Park (2020, p. 230)

- ^ Park (2020, pp. 231–232); McBride (2021, pp. 186–187)

- ^ Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 16)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 546); Park (2020, p. 233)

- ^ Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 17); Park (2020, p. 234); McBride (2021, p. 191)

- ^ Bentley, Joseph I. (1992). "Smith, Joseph: Legal Trials of Joseph Smith". In Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 1346–1348. ISBN 0-02-879602-0. OCLC 24502140. Retrieved May 5, 2023.; Oaks & Hill (1975, p. 18); Park (2020, p. 234)

- ^ McBride (2021, p. 192)

- ^ Oaks & Hill (1975, p. 52); Brodie (1971, p. 393)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 549)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 393–94); Bushman (2005, pp. 549–50)

- ^ Oaks & Hill (1975, p. 185)

References[edit]

- Anderson, Lavina Fielding, ed. (2001). Lucy's Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith's Family Memoir. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books.

- Arrington, Leonard; Bitton, Davis (1979). The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-46566-0..

- Avery, V.T.; Newell, L.K. (1980). "The Lion and the Lady: Brigham Young and Emma Smith". Utah Historical Quarterly. 48 (1): 81–97. doi:10.2307/45060927. JSTOR 45060927. S2CID 254428549. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- Bergera, Gary James, ed. (1989). Line Upon Line: Essays on Mormon Doctrine. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 0-941214-69-9.

- Bloom, Harold (1992). The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (1st ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-67997-2.

- Bringhurst, Newell G.; Foster, Craig L., eds. (2010). The Persistence of Polygamy: Joseph Smith and the Origins of Mormon Polygamy. Independence, MO: John Whitmer Books. ISBN 978-1-934901-13-7.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971). No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-46967-4.

- Brooke, John L. (1994). The Refiner's Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34545-6.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2004). Neilson, Reid L.; Woodworth, Jed (eds.). Believing History: Latter-day Saint Essays. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13006-6.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4270-4.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2008). Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Vol. 183. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531030-6.

- Compton, Todd (1997). In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-085-X.

- Coviello, Peter (2019). Make Yourselves Gods: Mormons and the Unfinished Business of American Secularism. Class 200. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47433-5.

- Davenport, Stewart (2022). Sex and Sects: The Story of Mormon Polygamy, Shaker Celibacy, and Oneida Complex Marriage. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-4705-1.

- Easton-Flake, Amy; Cope, Rachel (2020). "Reconfiguring the Archive: Women and the Social Production of the Book of Mormon". In MacKay, Michael Hubbard; Ashurst-McGee, Mark; Hauglid, Brian M. (eds.). Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith's Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press. pp. 105–134. ISBN 978-1-60781-743-7.

- Foster, Lawrence (1981). Religion and Sexuality: The Shakers, the Mormons, and the Oneida Community. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01119-1.

- Givens, Terryl L. (2014). Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794928.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-979492-8.

- Givens, Terryl; Hauglid, Brian M. (2019). The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism's Most Controversial Scripture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190603861.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-060386-1. OL 28940280M.

- Gutjahr, Paul C. (2012). The Book of Mormon: A Biography. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14480-1.

- Hales, Brian C. (2013). Joseph Smith's Polygamy. Vol. 1–3. With the assistance of Don Bradley. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford.

- Harper, Steven C. (2019). First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199329472.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-932947-2.

- Harris, Matthew L.; Bringhurst, Newell G., eds. (2015). The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09784-3.

- Hill, Donna (1977). Joseph Smith: The First Mormon. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co. ISBN 0-385-00804-X.

- Hill, Marvin S. (1989). Quest for Refuge: The Mormon Flight from American Pluralism. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-0-941214-70-4.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford History of the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- Howe, Eber Dudley (1834). Mormonism Unvailed: Or, A Faithful Account of that Singular Imposition and Delusion, from its Rise to the Present Time. Painesville, OH: Telegraph Press. OCLC 10395314.

- Jortner, Adam (2022). No Place for Saints: Mobs and Mormons in Jacksonian America. Witness to History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-4176-4.

- Larson, Stan (1978). "The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text". Brigham Young University Studies. 18 (2): 193–208. JSTOR 43040756.

- Mack, Solomon (1811). A Narraitve [sic] of the Life of Solomon Mack. Windsor, VT: Solomon Mack. OCLC 15568282.

- Marquardt, H. Michael; Walters, Wesley P (1994). Inventing Mormonism. San Francisco, CA: Smith Research Associates. ISBN 1-56085-108-2.

- Marquardt, H. Michael (1999). The Joseph Smith Revelations: Text and Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-126-4.

- Marquardt, H. Michael (2005). The Rise of Mormonism: 1816–1844. Grand Rapids, MI: Xulon Press. ISBN 1-59781-470-9.

- McBride, Spencer W. (2021). Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190909413.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-090941-3.

- Mueller, Max Perry (2017). Race and the Making of the Mormon People. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-3375-6 – via Project MUSE.

- Newell, Linda King; Avery, Valeen Tippetts (1994). Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith (2nd ed.). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06291-4.

- Oaks, Dallin H.; Hill, Marvin S. (1975). Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00554-6.

- Ostling, Richard; Ostling, Joan K. (1999). Mormon America: The Power and the Promise. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-066371-5.

- Park, Benjamin E. (2020). Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier. New York, NY: Liveright. ISBN 978-1-324-09110-3.

- Persuitte, David (2000). Joseph Smith and the Origins of the Book of Mormon. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-0826-X.

- Phelps, W.W., ed. (1833). A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ. Zion: William Wines Phelps & Co. OCLC 77918630. Archived from the original on May 20, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2005.

- Prince, Gregory A (1995). Power From On High: The Development of Mormon Priesthood. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-071-X.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1994). The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-056-6.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1998). Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-089-2.

- Remini, Robert V. (2002). Joseph Smith. Penguin Lives. New York, NY: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-03083-X.

- Shipps, Jan (1985). Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01417-0.

- Smith, George D. (1994). "Nauvoo Roots of Mormon Polygamy, 1841–46: A Preliminary Demographic Report" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 27 (1): 1–72. doi:10.2307/45228320. JSTOR 45228320. S2CID 254329894.

- Smith, George D (2008). Nauvoo Polygamy: "... But We Called It Celestial Marriage". Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-1-56085-201-8.

- Smith, Joseph, Jr. (1830). The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon, Upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi. Palmyra, New York, NY: E. B. Grandin. OCLC 768123849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See Book of Mormon. - Smith, Joseph, Jr. (1832). "History of the Life of Joseph Smith". In Jessee, Dean C (ed.). Personal Writings of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book (published 2002). ISBN 1-57345-787-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith, Joseph, Jr.; Cowdery, Oliver; Rigdon, Sidney; Williams, Frederick G., eds. (1835). Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints: Carefully Selected from the Revelations of God. Kirtland, Ohio: F. G. Williams & Co. OCLC 18137804.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) See Doctrine and Covenants. - Smith, Lucy Mack (1853). Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations. Liverpool: S.W. Richards. OCLC 4922747. See The History of Joseph Smith by His Mother

- Turner, John G. (2012). Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04967-3. OCLC 894538617 – via Internet Archive.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (2017). A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women's Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-74212-4.

- Van Wagoner, Richard S.; Walker, Steven C. (1982). "Joseph Smith: The Gift of Seeing" (PDF). Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 15 (2): 48–68. doi:10.2307/45225078. JSTOR 45225078. S2CID 254395171.

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1992). Mormon Polygamy: A History (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 978-0-941214-79-7.

- Vogel, Dan (2004). Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-179-1.

- Webb, Stephen H. (2011). Jesus Christ, Eternal God: Heavenly Flesh and the Metaphysics of Matter. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199827954.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-982795-4.

- Widmer, Kurt (2000). Mormonism and the Nature of God: A Theological Evolution, 1830–1915. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0776-7.