User:Teklae/Paradiso (Dante)

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft[edit]

Lead[edit]

Article body[edit]

Sixth Sphere (Jupiter: The Just Rulers)[edit]

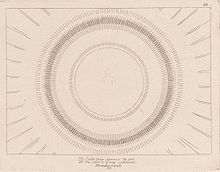

The planet Jupiter is traditionally associated with the king of the gods, so Dante makes this planet the home of the rulers who displayed justice.[1] The souls here spell out the Latin for "Love justice, ye that judge the earth", after which the final "M" of that sentence is transformed into the shape of a giant imperial eagle[1] (Canto XVIII):

DILIGITE IUSTITIAM were the verb

and noun that first appeared in that depiction;

QUI IUDICATIS TERRAM followed after.

Then, having formed the M of the fifth word,

those spirits kept their order; Jupiter's

silver, at that point, seemed embossed with gold.[2]

- ^ a b Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XVIII.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto XVIII, lines 91–96, Mandelbaum translation.

Present in this sphere are David, Hezekiah, Constantine, William II of Sicily, and surprisingly as well two pagans: Trajan (converted to Christianity according to a medieval legend), and (to Dante's amazement) Ripheus the Trojan, who was saved by the mercy of God in an act of predestination.[1] [2]Trajan has appeared in Divine Comedy before as an example of humility on terrace of pride. On this terrace, Dante sees Trajan surrounded by his soldiers on their way to a military conquest, but Trajan halts this after a grieving woman asks him to deliver justice to her son's murderers. [3] [2]The souls form the imperial eagle of divine justice. The eagle speaks with one voice, and tell of God's justice[4] (Cantos XIX and XX). At this point in his journey, Dante uses this opportune moment in front of the Eagle to ask about the inaccessibility of Heaven to people who were born before Christ or lived in an area where Christianity was not taught. Dante starts his question by creating an example of a contemporary of his, saying (Canto XIX):

A man is born on the banks

of the Indus, and no one is there to speak of

Christ to read or write of him,

and all his desires and acts are good, as far ashuman reason can see, without sin in life or in

word.

He dies unbaptized and without our faith:where is the justice that condemns him? where

is his fault if he does not believe?

Now who are you, who wish to sit on the benchand judge from a thousand miles away, with sight

as short as handbreadth?[5]

The shortcomings of Dante's contemporary is lack of faith and remaining unbaptized. Dante asks about accessibility to Heaven under difficult circumstance (no Christianity taught where one lives, or being born before Christ). If Dante were to live by the Indus banks, he would be the man in this example; an educated and knowledgable man who just happened to born in the wrong place for knowledge of ascension to Heaven. To answer Dante's complex question, the Eagle says (Canto XIX):

To this kingdom no one

has ever risen who did not believe in Christ,

either before or after he was nailed to the wood. [6]

At the very core of ascension is a belief that Jesus Christ is the Messiah. Depending on if someone was born before Christ or after, he or she at the very least would believe he would come to humanity's salvation or had come to humanity's salvation. This is the small opening that allows for people, like Dante's contemporary by the Indus bank, to ascend to Heaven. Dante can create as many contemporaries to his pleasing and ask the Eagle any hypothetical scenario, but this is the answer he will always get. A belief in Christ is the requirement for ascension.

From the Primum Mobile, Dante ascends to a region beyond physical existence, the Empyrean, which is the abode of God. Beatrice, representing theology,[7] is here transformed to be more beautiful than ever before. Her beauty, both religious and erotic, echoes the tradition of courtly lyric, which also pertains to her courtly role in the narrative that revolves around helping Dante and purifying him so he can ascend.[8] Dante becomes enveloped in light, first blinding him and then rendering him fit to see God[7] (Canto XXX).

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XX.

- ^ a b Raffa, Guy (2002). "Jupiter, under Paradiso". Danteworlds.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2003). Purgatorio. Translated by Durling. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. Canto X, 73–93.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XIX.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2003). Paradiso. Translated by Durling. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. Canto XIX, 70–81.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2003). Paradiso. Translated by Durling. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. Canto XIX, 103–5.

- ^ a b Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XXX.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda (2005-01-01). "Lifting the Veil? Notes toward a Gendered History of Early Italian Literature". Medieval Constructions in Gender and Identity: Essays in Honor of Joan M. Ferrante.

Dante sees an enormous rose, symbolising divine love,[1] the petals of which are the enthroned souls of the faithful (both those of the Old Testament and those of the New). All the souls he has met in Heaven, including Beatrice, have their home in this rose.[1] Ten women and eighth men occupy the Empyrean; the ladies appear in a hierarchy where Mary is the head and Eve is directly beneath her, followed by seven other Biblical women and Beatrice[2]. The noticeable outnumbering of men by women circles back to the beginning of Inferno, when many women appear in Limbo.[3] Angels fly around the rose like bees, distributing peace and love. Beatrice now returns to her place in the rose, signifying that Dante has passed beyond theology in directly contemplating God,[4] and St. Bernard, as a mystical contemplative, now guides Dante further (Canto XXXI), describing the heavenly rose and its occupants.[5] St. Bernard may represent God, since he welcomes the pilgrim to the Empyrean, after which Dante is able to see God; in this case, Beatrice would represent the Holy Spirit because she purifies Dante and brings him to St. Bernard and the Empyrean.[6]

St. Bernard further explains predestination, and prays to the Virgin Mary on Dante's behalf. The Empyrean as a whole contains heavy Marian imagery, such as the digits of Canto XXXII adding up to five, which may represent Mary because of her five-letter name—Maria—and experiences she had which notably came in sets of five.[2] St. Bernard's prayer, which includes an anaphora using the informal second-person pronoun, draws from a history of similar prayers beginning as early as Greek eulogies. In late Medieval Italy, poets such as Jacopone da Todi wrote praises of Mary called laude. Dante's prayer to the Virgin takes inspiration from this tradition and condenses its form, focusing first on Mary's role on Earth and then her role in Heaven and her motherly qualities.[7] Finally, Dante comes face-to-face with God Himself (Cantos XXXII and XXXIII). God appears as three equally large circles occupying the same space, representing the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit:[8]

but through my sight, which as I gazed grew stronger,

that sole appearance, even as I altered,

seemed to be changing. In the deep and bright

essence of that exalted Light, three circles

appeared to me; they had three different colors,

but all of them were of the same dimension;

one circle seemed reflected by the second,

as rainbow is by rainbow, and the third

seemed fire breathed equally by those two circles.[9]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

DLS30was invoked but never defined (see the help page).- ^ a b Kirkham, Victoria (1989). "A Canon of Women in Dante's "Commedia"". Annali d'Italianistica. 7: 16–41. ISSN 0741-7527.

- ^ Olson, Kristina (2020-01-01). "Conceptions of Women and Gender in the Comedy (uncorrected proofs)". Approaches to Teaching Dante's Divine Comedy, second edition.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XXXI.

- ^ Lansing, Richard. The Dante Encyclopedia. p. 99.

- ^ Seung, T. K. (1979). "The Epic Character of the Divina Commedia and the Function of Dante's Three Guides". Italica. 56 (4): 352–368. doi:10.2307/478663. ISSN 0021-3020.

- ^ AUERBACH, ERICH (1949). "Dante's Prayer to the Virgin (Paradiso, XXXIII) and Earlier Eulogies". Romance Philology. 3 (1): 1–26. ISSN 0035-8002.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XXXIII.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto XXXIII, lines 112–120, Mandelbaum translation.