User:SophiaGibbons/Emotion in animals/Bibliography

Emotion in non-human animals[edit]

Emotion is defined as any mental experience with high intensity and high hedonic content.[1] The existence and nature of emotions in non-human animals are believed to be correlated with those of humans and to have evolved from the same mechanisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to write about the subject, and his observational (and sometimes anecdotal) approach has since developed into a more robust, hypothesis-driven, scientific approach. Cognitive bias tests and learned helplessness models have shown feelings of optimism and pessimism in a wide range of species, including rats, dogs, cats, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings, pigs, and honeybees. Jaak Panksepp played a large role in the study of animal emotion, basing his research on the neurological aspect. Mentioning seven core emotional feelings reflected through a variety of neurodynamic limbic emotional action systems, including seeking, fear, rage, lust, care, panic and play.[2] Through brain stimulation and pharmacological challenges, such emotional responses can be effectively monitored.[2]

Emotion has been observed and further researched through multiple different approaches including that of behaviourism, comparative, anecdotal, specifically Darwin's approach and what is most widely used today the scientific approach which has a number of subfields including functional, mechanistic, cognitive bias tests, self-medicating, spindle neurons, vocalizations and neurology.

While emotions in animals is still quite a controversial topic it has been studied in a extensive array of species both large and small including primates, rodents, elephants, horses, birds, dogs, cats, honeybees and crayfish.

Behaviourist Approach[edit]

Behaviourists, such as John B. Watson, claim that stimulus–response models provide a sufficient explanation for animal behaviours that have been described as emotional, and that all behaviour, no matter how complex, can be reduced to a simple stimulus-response association. Watson described that the purpose of psychology was "to predict, given the stimulus, what reaction will take place; or given the reaction, state what the situation or stimulus is that has caused the reaction".

Scientific approach[edit]

Vocalizations[edit]

Though non-human animals cannot provide useful verbal feedback about the experiential and cognitive details of their feelings, various emotional vocalizations of other animals may be indicators of potential affective states.[2] Beginning with Darwin and his research, it has been known that chimpanzees and other great apes perform laugh-like vocalizations, providing scientists with more symbolic self-reports of their emotional experiences.[1]

Neurological[edit]

Neuroscientific studies based off of the instinctual, emotional action tendencies of non-human animals accompanied by the brains neurochemical and electrical changes are deemed to best monitor relative primary process emotional/affective states.[2] Predictions based off the research conducted on animals is what leads analysis of the neural infrastructure relevant in humans. Psycho-neuro-ethological triangulation with both humans and animals allows for further experimentation into animal emotions. Utilizing specific animals that exhibit indicators of emotional states to decode underlying neural systems aids in the discovery of critical brain variables that regulate animal emotional expressions. Comparing the results of the animals converse experiments occur predicting the affective changes that should result in humans.[2] Specific studies where there is an increase or decrease of playfulness or separation distress vocalizations in animals, comparing humans that exhibit the predicted increases or decreases in feelings of joy or sadness, the weight of evidence constructs a concrete neural hypothesis concerning the nature of affect supporting all relevant species.[2]

Species Examples[edit]

Elephants[edit]

Elephants are known for their empathy towards members of the same species as well as their cognitive memory. While this is true scientists continuously debate the extent to which elephants feel emotion. Observations show that elephants, like humans, are concerned with distressed or deceased individuals, and render assistance to the ailing and show a special interest in dead bodies of their own kind, however this view is interpreted as being anthropomorphic. [3] Elephants have recently been suggested to pass mirror self-recognition tests, and such tests have been linked to the capacity for empathy. However, it should be noted that the experiment showing such actions did not follow the accepted protocol for tests of self-recognition, and earlier attempts to show mirror self-recognition in elephants have failed, so this remains a contentious claim. [4] Elephants are also deemed to show emotion through vocal expression, specifically the rumble vocalization. Rumbles are frequency modulated, harmonically rich calls with fundamental frequencies in the infrasonic range, with clear formant structure. Elephants exhibit negative emotion and/or increased emotional intensity through their rumbles, based on specific periods of social interaction and agitation. [5]

Cats[edit]

It has been postulated that domestic cats can learn to manipulate their owners through vocalizations that are similar to the cries of human babies. Some cats learn to add a purr to the vocalization, which makes it less harmonious and more dissonant to humans, and therefore harder to ignore. Individual cats learn to make these vocalizations through trial-and-error; when a particular vocalization elicits a positive response from a human, the probability increases that the cat will use that vocalization in the future.

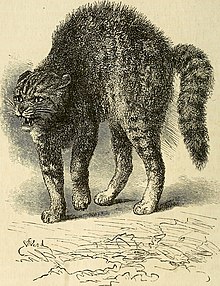

Growling can be an expression of annoyance or fear, similar to humans. When annoyed or angry, a cat wriggles and thumps its tail much more vigorously than when in a contented state. In larger felids such as lions, what appears to be irritating to them varies between individuals. A male lion may let his cubs play with his mane or tail, or he may hiss and hit them with his paws. Domestic male cats also have variable attitudes towards their family members, for example, older male siblings tend not to go near younger or new siblings and may even show hostility toward them.

Hissing is also a vocalization associated with either offensive or defensive aggression. They are usually accompanied by a postural display intended to have a visual effect on the perceived threat. Cats hiss when they are startled, scared, angry, or in pain, and also to scare off intruders into their territory. If the hiss and growl warning does not remove the threat, an attack by the cat may follow. Kittens as young as two to three weeks will potentially hiss when first picked up by a human. [6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Cabanac, Michel (2002). "What is emotion?". Behavioural Processes. 60 (2): 69–83. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(02)00078-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Panksepp, Jaak (2005). "Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans". Consciousness and Cognition. 14 (1): 30–80. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Bhalla, Shivani; Wittemyer, George; Vollrath, Fritz (2006). "Behavioural reactions of elephants towards a dying and deceased matriarch". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 100 (1–2): 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.04.014. ISSN 0168-1591.

- ^ Bates, L, A. (2008). "Do Elephants Show Empathy?". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 15: 204–225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Altenmüller, Eckart. Schmidt, Sabine. Zimmermann, Elke. (2013). Evolution of emotional communication from sounds in nonhuman mammals to speech and music in man. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-174748-9. OCLC 940556012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wikipedia, Source. (2013). Cat behavior : cats and humans, cat communication, cat intelligence, cat pheromone, cat. University-Press Org. ISBN 1-230-50106-1. OCLC 923780361.