User:Smerus/brahms

Johannes Brahms (German: [joˈhanəs ˈbʁaːms]; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer and pianist. Born in Hamburg , Brahms spent much of his professional life after 1862 in Vienna.

Life[edit]

Early years (1833-1850)[edit]

Brahms's father, Johann Jakob Brahms (1806–72), was from the town of Heide in Holstein. The family name was also sometimes spelt 'Brahmst' or 'Brams', and derives from 'Bram', the German word for the shrub broom.[1] Johann Jakob, against the family's will, pursued a career in music, arriving in Hamburg in 1826, where he found work as a jobbing musician a a string and wind player. In 1830, he married Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen (1789–1865), a seamstress 17 years older than he was. In the same year he was appointed as a horn player in the Hamburg militia.[2] Eventually he became a double-bass player in the Hamburg Stadttheater and the Hamburg Philharmonic Society. As Johann Jakob prospered, the family moved over the years to ever better accommodation in Hamburg.[3] Johannes Brahms was born in 1833; he his sister Elisabeth (Elise) had been born in 1831 and a younger brother brother Fritz Friedrich (Fritz) was born in 1835.[4] Fritz also became a pianist; overshadowed by his brother he emigrated to Caracas in 1867, and later returned to Hamburg as a teacher.[5]

Johann Jakob gave his son his first musical training; Johannes also learnt to play the violin and the basics of playing the cello. From 1840 he studied piano with Otto Friedrich Willibald Cossel (1813-1865). Cossel complained in 1842 that Brahms "could be such a good player, but he will not stop his never-ending composing." These early compositions were to include by 1845 a piano sonata in G minor. At the age of 10, Brahms made his debut as a performer in a private concert including Beethoven's quintet for piano and winds Op. 16 and a piano quartet by Mozart. He also played as a solo work an étude of Henri Herz. By 1845 he had written a piano sonata in G minor.[6] Brahms's parents disapproved of his early efforts as a composer, feeling that he had better career prospects as a performer.[7]

From 1845-1848 Brahms studied with Cossel's teacher the pianist and composer Eduard Marxsen (1806-1887). Marxsen had been a personal acquaintance of Beethoven and Schubert, admired the works of Mozart and Haydn, and was a devotee of the music of J. S. Bach. Marxsen conveyed to Brahms the tradition of these composers and ensured that Brahms's own compositions were grounded in that tradition.[8] In 1847 Brahms made his first public appearance as a solo pianist in Hamburg, playing a Fantasy of Sigismund Thalberg. His first full piano recital, in 1848, included a fugue by Bach as well as works by Marxsen and contemporary virtuosi such as Jacob Rosenhain. A second recital in April 1849 included Beethoven's Waldstein sonata and a waltz fantasia of his own composition, and garnered favourable newspaper reviews.[9]

Brahms's compositions at this period are known to have included piano music, chamber music and works for male voice choir. Under the pseudonym 'G.W. Marks' some piano arrangements and fantasies were published by the Hamburg firm of Cranz in 1849. The earliest of Brahms's works which he acknowledged (his Scherzo Op. 4 and the song Heimkehr Op. 7 no. 6) date from 1851. However Brahms was later assiduous in eliminating all his early works; even as late as 1880 he wrote to his friend Elise Giesemann to send him his manuscripts of choral music so that they could be destroyed.[10]

Lurid stories of the impoverished adolescent Brahms playing in bars and brothels have only anecdotal provenance, and modern scholars dismiss them; the Brahms family was relatively prosperous, and Hamburg legislation in any case very strictly forbade music in, or the admittance of minors to, brothels.[11][12]

Early career (1850-1862)[edit]

In 1850 Brahms met with the Hungarian Jewish violinist Ede Reményi and accompanied him in a number of recitals over the next few years. This was Brahms's introduction to the music of 'gipsy-style' music such as the czardas, which was later to prove the foundation of his most lucrative and popular compositions, the two sets of Hungarian Dances (1869 and 1880).[13] 1850 also marked Brahms's first contact (albeit a failed one) with Robert Schumann; during Schumann's visit to Hamburg that year, friends persuaded Brahms to send the former some of his compositions, but the package was returned unopened.[14]

In 1853 Brahms went on a concert tour with Reményi. In late May the two visited the violinist and composer Joseph Joachim at Hanover. Brahms had earlier heard Joachim playing the solo part in Beethoven's violin concerto and been deeply impressed.[15] Brahms played some of his own solo piano pieces for Joachim, who fifty years after remembered "Never in the course of my artist's life have I been more completely overwhelmed".[16] This was the beginning of a friendship which was life-long, albeit temporarily derailed when Brahms took the part of Joachim's wife in their divorce proceedings of 1883.[17] Brahms also admired Joachim as a composer, and in 1856 they were to embark on a mutual training exercise to improve their skills in (in Brahms's words) "double counterpoint, canons, fugues, preludes or whatever".[18] Bozarth notes that "products of Brahms's study of counterpoint and early music over the next few years included "dnce pieces, preludes and fugues for organ, and neo-Renaissance and neo-Baroque choral works."[19]

After meeting Joachim, Brahms and Reményi visited Weimar where Brahms met Franz Liszt, Peter Cornelius, and Joachim Raff, and where Liszt performed Brahms's Op. 4 Scherzo at sight. Reményi claimed that Brahms then slept during Liszt's performance of his own Sonata in B minor; this and other disagreements led to Reményi and Brahms parting company.[20]

Brahms visited Düsseldorf in October 1853, and, provided by a letter of introduction from Joachim[21] was welcomed by Schumann and his wife Clara. Schumann, greatly impressed and delighted by the 20-year-old's talent, published an article entitled "Neue Bahne" ("New Paths") in the 28 October issue of the journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik nominating Brahms as one who was "fated to give give expression to the times in the highest and most ideal manner."[22] This praise may have aggravated Brahms's self-critical standards of perfection and dented his confidence. He wrote to Schumann in November 1853 that his praise "will arouse such extraordinary expectations by the public that I don't know how I can begin to fulfil them."[23] While in Düsseldorf, Brahms participated with Schumann and Schumann's pupil Albert Dietrich in writing a movement each of a violin sonata for Joachim, the "F-A-E Sonata", the letters representing the initials of Joachim's personal motto "Frei aber einsam" ("Free but Alone").[24] Schumann's accolade led to the first publication of Brahms's works under his own name. Brahms went to Leipzig where Breitkopf and Härtel published his Opp. 1-4 (the Piano Sonatas nos. 1 and 2, the Six Songs Op. 3, and the Scherzo Op. 4), whilst Bartholf Senff published the Third Piano Sonata Op. 5 and the Six Songs Op. 6. In Leipzig he gave recitals including his own first two piano sonatas, and met with amongst others Ferdinand David, Ignaz Moscheles and Hector Berlioz.[25][19]

After Schumann's attempted suicide and subsequent confinement in a mental sanatorium near Bonn in February 1854 (where was to die in 1856), Brahms based himself in Düsseldorf, where he supported the household and dealt with business matters on Clara's behalf. Clara was not allowed to visit Robert until two days before his death; Brahms was able to visit him and acted as a go-between. Brahms began to feel deeply for Clara, who to him represented an ideal of womanhood. Their intensely emotional relationship, which however seems never to have moved beyond close friendship, would last until Clara's death. In June 1854 Brahms dedicated to Clara his Op. 9, the Variations on a Theme of Schumann.[19] Clara continued to support Brahms's career by programming his music in her recitals.[26]

After the publication of his Op. 10 Ballades for piano, Brahms published no further works until 1860. His major project of this period was the Piano Concerto in D minor, which he had begun as a work for two pianos in 1854 but soon realized needed a larger-scale format. Based in Hamburg for this period, he gained a position with Clara's support as musician to the tiny court of Detmold, the capital of the Principality of Lippe, where he spent the winters of 1857-1860 and for which he wrote his two Serenades (1858 and 1859, Opp. 11 and 16). In Hamburg he established a women's choir for which he wrote music and conducted. To this period also belong his first two Piano Quartets (Op. 25 and Op. 26) and the first movement of the third Piano Quartet, which eventually appeared in 1875.[19]

The end of the decade brought professional setbacks for Brahms. The premiere of the First Piano Concerto in Hamburg on 22nd January 1859, with the composer as soloist, was poorly received. Brahms wrote to Joachim that the performance was "a brilliant and decisive - failure...[I]t forces one to concentrate one's thoughts and increases one's courage...But the hissing was too much of a good thing..."[27] At a second performance, audience reaction was so hostile that Brahms had to be restrained from leaving the stage after the first movement.[28] As a consequence of these reactions Breitkopf and Härtel declined to take on his new compositions; Brahms consequently established a relationship with other publishers, including with Simrock who eventually became his major publishing partner.[19] Brahms further made an intervention in 1860 in the debate on the future of German music which seriously misfired. He prepared together with Joachim and others an attack on Liszt's followers, the so-called "New German School" (although Brahms himself was sympathetic to the music of Richard Wagner, the School's leading light). In particular they objected to the rejection of traditional musical forms and to the "rank, miserable weeds growing from Liszt-like fantasias." A draft was leaked to the press, and the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik published a parody which ridiculed Brahms and his associates as backward-looking. Brahms never again ventured into public musical polemics.[29]

Brahms's personal life was also troubled. In 1859 he became engaged to Agathe von Siebold. The engagement was soon broken off, but even after this Brahms wrote to her: "I love you! I must see you again, but I am incapable of bearing fetters. Please write me ... whether ... I may come again to clasp you in my arms, to kiss you, and tell you that I love you." They never saw one another again, and Brahms later confirmed to a friend that Agathe was his "last love."[30]

Maturity (1862-1876)[edit]

Brahms had hoped to be given the conductorship of the Hamburg Philharmonic, but in 1862 this post was given to the baritone Julius Stockhausen. (Brahms continued to hope for the post; but when he was finally offered the directorship in 1893, he demurred as he had "got used to the idea of having to go along other paths".)[31] In autumn 1862 Brahms made his first visit to Vienna, staying there over the winter. There he became an associate of two close members of Wagner's circle, his earlier friend Peter Cornelius and Karl Tausig, and of Joseph Hellmesberger and Julius Epstein, respectively the Director and head of violin studies at the Vienna Conservatoire. Brahms's circle grew to include the notable critic (and opponent of the 'New German School') Eduard Hanslick, the conductor Hermann Levi and the surgeon Theodor Billroth, who were to become amongst his greatest advocates.[32][33]

In January 1863 came Brahms's first meeting with Richard Wagner, playing him his Handel Variations Op. 24, which he had completed the previous year. The meeting was cordial, although Wagner was in later years to make critical, and even insulting, comments on Brahms's music.[34] Brahms however retained at this time and later a keen interest in Wagner's music, helping with preparations for Wagner's Vienna concerts in 1862-3[33], and being rewarded by Tausig with a manuscript of part of Wagner's Tannhäuser (which Wagner demanded back in 1875).[35] The Handel Variations also featured, together with the first Piano Quartet, in Brahms's first Viennese recitals, in which his performances were better-received by the public and critics than his music.[36]

Although Brahms entertained the idea of taking up conducting posts elsewhere, he based himself increasingly in Vienna and soon made it his home there. In 1863, he was appointed conductor of the Vienna Singakademie. He surprised his audiences by programming much work of the early German masters such as J. S. Bach and Heinrich Schütz and other early composers such as Giovanni Gabrieli; more recent music was represented by works of Beethoven and Felix Mendelssohn. He also wrote works for the choir, including his Op. 29 "Motet". Finding however that the post encroached too much of the time he needed for composing, he left the choir in June 1864.[37] From 1864 to 1876 he spent many of his summers in Lichtental, Baden-Baden, where Clara Schumann and her family also spent some time. His house in Lichtental, where he worked on many of his major compositions including A German Requiem and his middle-period chamber works is today preserved as a museum.[38]

In February 1865 Brahms's mother died, and he began to compose his large choral work A German Requiem Op. 45, of which six movements were completed by 1866. Premieres of the first three movements were given in Vienna, but the complete work was first given in Bremen in 1868 to great acclaim. A seventh movement (the soprano solo "Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit") was added for the equally successful Leipzig premiere (February 1869), and the work went on to receive concert and critical acclaim throughout Germany and also in England, Switzerland and Russia, marking effectively Brahms's arrival on the world stage.[33] Brahms also experienced at this period popular success with works such as his first set of Hungarian Dances (1865), the Liebeslieder Walzer Op. 52 (1868-9), and his collections of lieder (Opp. 43 and 46-49).[33] Following such successes he finally completed a number of works that he had wrestled with over many years such as the cantata Rinaldo (1863-1868), his first two string quartets Op. 51 nos. 1 and 2 (1865-1873), the third piano quartet (1855-1875), and most notably his first symphony which appeared in 1876, but which had been begun as early as 1855.[39][40]

From 1872 to 1875, Brahms was director of the concerts of the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. He ensured that the orchestra was staffed only by professionals, and conducted a repertoire which ran from Bach to the nineteenth century composers who were not of the 'New German School'; these included Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Joachim, Ferdinand Hiller, Max Bruch and himself (notably his large scale choral works, the German Requiem, the Alto Rhapsody Op. 53 and the patriotic Triumphlied Op. 55 which celebrated Prussia's victory in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War.[40] 1873 saw the premiere of his orchestral Variations on a Theme by Haydn, originally conceived fpor wwo pianos, whuch has become one of his most popular works.[40][41]

Years of fame (1876-1890)[edit]

Brahms's first symphony appeared in 1876, though it had been begun (and a version of the first movement had been announced by Brahms to Clara and to Albert Dietrich) in the early 1860s. During the decade it evolved very gradually; the finale may not have begun its conception until 1868.[42] Brahms was cautious and typically self-deprecating about the symphony during its creation, writing to his friends that it was"long and difficult", "not exactly charming" and, significantly "long and in C Minor", which,as Richard Taruskin points out made it clear "that Brahms was taking on the model of models [for a symphony]: Beethoven's Fifth."[43] Despite the warm reception it received, Brahms remained dissatisfied and extensively revised the second movement before the work was published. There followed a succession of well-received orchestral works; the Second Symphony Op. 73 (1877), the Violin concerto Op. 77 (1878), dedicated to Joachim who was consulted closely during its composition, and the Academic Festival Overture (written following the conferring of an honorary degree by the University of Breslau) and Tragic Overture of 1880. The commendation of Brahms by Breslau as "the leader in the art of serious music in Germany today" led to a bilious comment from Wagner in his essay "On Poetry and Composition": "I know of some famous composers who in their concert masquerades don the disguise of a street-singer one day, the hallelujah periwig of Handel the next , the dress of a Jewish Czardas-fiddler another time, and then again the guise of a highly respectable symphony dressed up as Number Ten" (referring to Brahms's First Symphony as a putative tenth symphony of Beethoven).[44]

Brahms was now recognised as a major figure in the world of music. He had been on the jury which awarded the Vienna State Prize to the (then little-known) composer Antonín Dvořák three times, first in February 1875, and later in 1876 and 1877 and had successfully recommended Dvořák to his publisher, Simrock. The two men met for the first time in 1877, and Dvořák dedicated to Brahms his String Quartet, Op. 44 of that year.[45] He also began to be the recipient of a variety of honours; Ludwig II of Bavaria awarded him the Order of Maximilian in 1874, Cambridge University offered him an honorary degree (in 1877 - he did not accept it as he was unable to travel to England), and the music loving Duke George of Meiningen awarded him in 1881 the Commander's Cross of the Order of the House of Meiningen.[46]

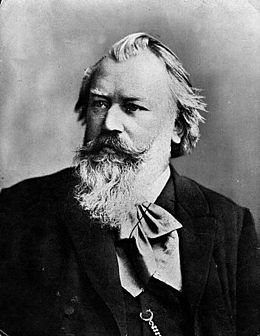

At this time Brahms also chose to change his image. Having been always clean-shaven, in 1878 he surprised his friends by growing a beard, writing in September to the conductor Bernhard Scholz "I am coming with a large beard! Prepare your wife for a most awful sight."[47] The singer George Henschel recalled that after a concert "I saw a man unknown to me, rather stout, of middle height, with long hair and a full beard. In a very deep and hoarse voice he introduced himself as 'Musikdirektor Müller'... an instant later, we all found ourselves laughing heartily at the perfect success of Brahms's disguise". The incident also displays Brahms's love of practical jokes.[48]

Brahms's bachelor life in Vienna had by now led him to a regular daily round, which he coupled with a guarded personality. He lunched every day at the inn "Zum rote Igel" ("The Red Hedgehog") after a morning of work, and spent the rest of the day at leisure, walking or reading the papers, returning home sometimes in the early evening for further work. If he attended a concert or opera in the evening, he would frequently then return to the "Rote Igel" with some friends.[49] He could be brusque and sarcastic with those outside his circle.. His pupil Gustav Jenner noted that "it would be untrue if I were to say that Brahms was always polite to his visitors"[50]

In 1882 Brahms completed his Piano Concerto No. 2 Op. 83, dedicated to his teacher Marxsen.[40] Brahms was invited by Hans von Bülow to undertake a premiere of the work with the Meiningen Court Orchestra; this was the beginning of his collaboration with Meiningen and with von Bülow, who was to rank Brahms as one of the 'Three Bs'; in a letter to his wife he wrote "You know what I think of Brahms: after Bach and Beethoven the greatest, the most sublime of all composers." [51] The following years saw the premieres of his Third Symphony Op. 90 (1883) and his Fourth Symphony Op. 98 (1885). Richard Strauss, who had been appointed assistant to von Bülow at Meiningen, and had been uncertain about Brahms's music, found himself converted by the Third Symphony and was enthusiastic about the Fourth: "a giant work, great in concept and invention."[52] Another, but cautious, supporter from the younger generation was Gustav Mahler who first met Brahms in 1884 and remained a close acquaintance; he rated Brahms as superior to Anton Bruckner, but more earth-bound than Wagner and Beethoven.[53]

In 1889, Theo Wangemann, a representative of American inventor Thomas Edison, visited the composer in Vienna and invited him to make an experimental recording. Brahms played an abbreviated version of his first Hungarian Dance and of Josef Strauss's Die Libelle on the piano. Although the spoken introduction to the short piece of music is quite clear, the piano playing is largely inaudible due to heavy surface noise.[54] Analysts and scholars remain divided as to whether the voice that introduces the piece is that of Wangemann or of Brahms.[55] In the same year, Brahms was named an honorary citizen of Hamburg, until 1948 the only one born in Hamburg.[56]

Last years (1890-1897)[edit]

Brahms had become acquainted with Johann Strauss II, who was eight years his senior, in the 1870s, but their close friendship belongs to the years 1889 and after. Brahms admired much of Strauss's music, and encouraged the composer to sign up with his publisher Simrock. In autographing a fan for Strauss's wife Adele, Brahms wrote the opening notes of notes of The Blue Danube waltz adding the words "unfortunately not by Johannes Brahms".[57]

After the successful Vienna premiere of his Second String Quintet, op. 111, in 1890, the 57-year-old Brahms came to think that he might retire from composition, telling a friend that he "had achieved enough; here I had before me a carefree old age and could enjoy it in piece.".[58] He also began to find solace in escorting the mezzo-soprano Alice Barbi and may have proposed to her (she was only 28).[59] However, his admiration for Richard Mühlfeld, clarinetist with the Meiningen orchestra, moved him to compose the Clarinet Trio, Op. 114, Clarinet Quintet, Op. 115 (1891), and the two Clarinet Sonatas, Op. 120 (1894). Brahms also wrote at this time his final cycles of piano pieces, Opp. 116–119, the Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), Op. 121 (1896) (which were prompted by the death of Clara Schumann),[60] and the Eleven Chorale Preludes for organ, Op. 122 (1896). Many of these works were written in his house in Bad Ischl, where Brahms had first visited in 1882 and where he spent every summer from 1889 onwards.[61]

In the summer of 1896 Brahms was diagnosed as having jaundice, but later in the year his Viennese doctor diagnosed him as having cancer of the liver (from which his father Jakob had died).[62] Brahms's last public appearance was on 3 March 1897, when he saw Hans Richter conduct his Symphony No. 4. There was an ovation after each of the four movements. He made the effort, three weeks before his death, to attend the premiere of Strauss's operetta Die Göttin der Vernunft in March 1897.[57] His condition gradually worsened and he died a month later, on 3 April 1897, aged 63. Brahms is buried in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna, under a monument by Victor Horta and the sculptor Ilse von Twardowski-Conrat.[63]

Music[edit]

Pianist[edit]

Brahms's individual style of piano-playing, which first brought him to attention, also lay at the heart of his style as a composer. One listener wrote in the 1850s "He does not play like a consummately trained ....musician making other people's works his own...but rather like one who is himself creating, who interprets the works of a master as an equal."[64]

J. Barrie Jones attributes Brahms's success as a composer to "his enthusiastic championship by the Schumanns, his early emergence into maturity, his considerable powers as a pianist... and his unrelenting self-criticism".[65]

Brahms maintained a classical sense of form and order in his works, in contrast to the opulence of the music of many of his contemporaries. Thus, many admirers (though not necessarily Brahms himself) saw him as the champion of traditional forms and "pure music", as opposed to the "New German" embrace of programme music.

Brahms was a master of counterpoint. "For Brahms, ... the most complicated forms of counterpoint were a natural means of expressing his emotions," writes Geiringer. "As Palestrina or Bach succeeded in giving spiritual significance to their technique, so Brahms could turn a canon in motu contrario or a canon per augmentationem into a pure piece of lyrical poetry."[66] Writers on Brahms have commented on his use of counterpoint. For example, of Op. 9, Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Geiringer writes that Brahms "displays all the resources of contrapuntal art".[67] In the A Major piano quartet Opus 26, Swafford notes that the third movement is "demonic-canonic", echoing Haydn's famous minuet for string quartet called the 'Witch's Round'."[68] Swafford further opines that "thematic development, counterpoint, and form were the dominant technical terms in which Brahms... thought about music".[69]

Brahms loved the classical composers Mozart and Haydn. He collected first editions and autographs of their works and edited performing editions. He studied the music of pre-classical composers, including Giovanni Gabrieli, Johann Adolph Hasse, Heinrich Schütz, Domenico Scarlatti, George Frideric Handel, and, especially, Johann Sebastian Bach. His friends included leading musicologists, and, with Friedrich Chrysander, he edited an edition of the works of François Couperin. Brahms also edited works by C. P. E. Bach and W. F. Bach. He looked to older music for inspiration in the art of counterpoint; the themes of some of his works are modelled on Baroque sources such as Bach's The Art of Fugue in the fugal finale of Cello Sonata No. 1 or the same composer's Cantata No. 150 in the passacaglia theme of the Fourth Symphony's finale.

The early Romantic composers had a major influence on Brahms, particularly Schumann, who encouraged Brahms as a young composer. During his stay in Vienna in 1862–63, Brahms became particularly interested in the music of Franz Schubert.[70] The latter's influence may be identified in works by Brahms dating from the period, such as the two piano quartets Op. 25 and Op. 26, and the Piano Quintet which alludes to Schubert's String Quintet and Grand Duo for piano four hands.[70][71] The influence of Chopin and Mendelssohn on Brahms is less obvious, although occasionally one can find in his works what seems to be an allusion to one of theirs (for example, Brahms's Scherzo, Op. 4, alludes to Chopin's Scherzo in B-flat minor;[72] the scherzo movement in Brahms's Piano Sonata in F minor, Op. 5, alludes to the finale of Mendelssohn's Piano Trio in C minor).[73]

Brahms considered giving up composition when it seemed that other composers' innovations in extended tonality would result in the rule of tonality being broken altogether. Although Wagner became fiercely critical of Brahms as the latter grew in stature and popularity, he was enthusiastically receptive of the early Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel; Brahms himself, according to many sources,[74] deeply admired Wagner's music, confining his ambivalence only to the dramaturgical precepts of Wagner's theory.

Brahms wrote settings for piano and voice of 144 German folk songs, and many of his lieder reflect folk themes or depict scenes of rural life. His Hungarian Dances were among his most profitable compositions.

Legacy[edit]

The British composer Hubert Parry, who considered Brahms the greatest artist of the time, wrote an orchestral Elegy for Brahms in 1897. This was never played in Parry's lifetime, receiving its first performance at a memorial concert for Parry himself in 1918.[citation needed]

From 1904 to 1914, Brahms's friend, the music critic Max Kalbeck published an eight-volume biography of Brahms, but this has never been translated into English.[citation needed] Between 1906 and 1922, the Deutsche Brahms-Gesellschaft (German Brahms Society) published 16 numbered volumes of Brahms's correspondence, at least 7 of which were edited by Kalbeck. An additional 7 volumes of Brahms's correspondence were published later, including two volumes with Clara Schumann, edited by Marie Schumann.[75]

Ferruccio Busoni's early music shows much Brahmsian influence, and Brahms took an interest in him, though Busoni later tended to disparage Brahms. Towards the end of his life, Brahms offered substantial encouragement to Ernő Dohnányi and to Alexander von Zemlinsky. Their early chamber works (and those of Béla Bartók, who was friendly with Dohnányi) show a thoroughgoing absorption of the Brahmsian idiom. Zemlinsky, moreover, was in turn the teacher of Arnold Schoenberg, and Brahms was apparently impressed by drafts of two movements of Schoenberg's early Quartet in D major which Zemlinsky showed him in 1897. In 1933, Schoenberg wrote an essay "Brahms the Progressive" (re-written 1947), which drew attention to Brahms's fondness for motivic saturation and irregularities of rhythm and phrase; in his last book (Structural Functions of Harmony, 1948), he analysed Brahms's "enriched harmony" and exploration of remote tonal regions. These efforts paved the way for a re-evaluation of Brahms's reputation in the 20th century. Schoenberg went so far as to orchestrate one of Brahms's piano quartets. Schoenberg's pupil Anton Webern, in his 1933 lectures, posthumously published under the title The Path to the New Music, claimed Brahms as one who had anticipated the developments of the Second Viennese School, and Webern's own Op. 1, an orchestral passacaglia, is clearly in part a homage to, and development of, the variation techniques of the passacaglia-finale of Brahms's Fourth Symphony.

Brahms was honoured in the German hall of fame, the Walhalla memorial. On 14 September 2000, he was introduced there as the 126th "rühmlich ausgezeichneter Teutscher" and 13th composer among them, with a bust by sculptor Milan Knobloch.[76]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 7.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), pp. 3-4.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), pp. 4-8.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 14-16.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 13.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), pp. 9-11.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), p. 12.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 26.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), pp. 17-18.

- ^ Hofmann (1999), p.16, pp. 18-20.

- ^ Swafford (2001), passim.

- ^ Hofmann (1999) pp. 12-14.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 56, p. 62; Musgrave (1999b), p. 45.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 56-7.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 49.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 64.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 494-495.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Bozarth (n.d.), §2: "New Paths".

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 67, p. 71

- ^ Gál (1963), p. 7

- ^ Schumann (1988), p. 199-200.

- ^ Avins (1997), p. 24

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 81-82.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 89

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 180, p. 182.

- ^ Swafford (1997), pp. 189–190.

- ^ Swafford (1997), p.211.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 206–211.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), pp. 52-53.

- ^ .Musgrave (2000), pp. 27, 31.

- ^ Musgrave (1999b), pp. 39-41.

- ^ a b c d Bozarth (n.d.), §3 "First maturity"

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 265-269.

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 401.

- ^ Musgrave (1999b), p. 39.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp.277-279, 283.

- ^ Hofmann (2010), p. 40; "Brahms House", on website of the Schumann Portal, accessed 22 December 2016.

- ^ Becker (1980), pp. 174-179.

- ^ a b c d Bozarth (n.d.). §4, "At the summit"

- ^ Swafford (1999), p. 383.

- ^ Musgrave (1999b), pp. 42-43.

- ^ Taruskin (2010), p. 694.

- ^ Taruskin (2010), p. 729.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 444-446

- ^ Musgrave (1999), p. xv; Musgrave (2000), p. 171; Swafford (1999), p. 467

- ^ Hofmann (2010), p. 57.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 4, p. 6.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 42.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 41.

- ^ Swafford (1999), pp. 465-6.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 252.

- ^ Musgrave (2000), pp. 253-4.

- ^ J. Brahms plays excerpt of Hungarian Dance No. 1 (2:10) on YouTube

- ^ Several attempts have been made to improve the quality of this historic recording; a "denoised" version was produced at Stanford University. "Brahms at the Piano" by Jonathan Berger (CCRMA, Stanford University)

- ^ http://fhh.hamburg.de/stadt/Aktuell/senat/service/ehrenbuerger/start.html Stadt Hamburg Ehrenbürger] (in German) Retrieved 17 June 2008

- ^ a b Lamb (1975), pp. 869-870

- ^ Swafford (1997), pp. 568-9.

- ^ Swafford (1997), p. 569.

- ^ Swafford (1997), pp. 607-8.

- ^ Hofmann (2010), p. 42.

- ^ Swafford (1997), pp. 614-5.

- ^ Zentralfriedhof group 32a, details

- ^ Musgrave (2000), p. 122.

- ^ Jones (1998), p. 157.

- ^ Geiringer (1981), p. 159

- ^ Geiringer, p. 210.

- ^ Swafford (2012), p. 159.

- ^ Swafford (2012), p. xviii

- ^ a b James Webster, "Schubert's sonata form and Brahms's first maturity (II)", 19th-Century Music 3(1) (1979), pp. 52–71.

- ^ Donald Francis Tovey, "Franz Schubert" (1927), rpt. in Essays and Lectures on Music (London, 1949), p. 123. Cf. his similar remarks in "Tonality in Schubert" (1928), rpt. ibid., p. 151.

- ^ Charles Rosen, "Influence: plagiarism and inspiration", 19th-Century Music 4(2) (1980), pp. 87–100.

- ^ H. V. Spanner, "What is originality?", The Musical Times 93(1313) (1952), pp. 310–311.

- ^ Swafford (1999)

- ^ "Johannes Brahms – Wikisource", http://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Johannes_Brahms (in German). There are two volumes of correspondence with Joachim, and four volumes with Brahms's main publisher, Simrock

- ^ "Johannes Brahms hält Einzug in die Walhalla". Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst. 14 September 2000. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

Sources[edit]

- Avins, Styra (ed.), (1997). Johannes Brahms: Life and Letters (1997). Translated by Joseph Eisinger and S. Avins. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198162346

- Avins, Styra (2001). "The Young Brahms: Biographical Data Reexamined". 19th-Century Music. 24 (3): 276–289. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.276. JSTOR 746931.

- Becker, Heinz (1980). "Brahms, Johannes", in New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, vol. 3, pp. 154–190. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333231112

- Bozarth, Geroge S. (n.d.). "Brahms, Johannes" in Grove Music Online. (subscription required) Accessed 7 November 2016.

- Chrissochoidis, Ilias (2012). "A Master stands: Rare Brahms Photos in the Library of Congress", Fontes Artis Musicae 59/1 (January–March 2012), pp. 39–44. Accessed 4 November 2016.

- Frisch, Walter and Karnes, Kevin C., (eds.), (2009).Brahms and His World (Revised Edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691143446

- Gál, Hans, (1963). Johannes Brahms: His Work and Personality. Tr. Joseph Stein. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

- Geiringer, Karl, (1981). Brahms: His Life and Work, Third Ed. New York: Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-80223-6

- Hofmann, Kurt, tr. Michael Musgrave (1999). "Brahms the Hamburg musician 1833-1862". In Musgrave (1999a), pp. 3-30.

- Hofmann, Kurt and Renate Hofmann, tr. Trefor Smith (2010). "Brahms Museum Hamburg: Exhibition Guide." Hamburg: Johannes-Brahms-Gesellschaft.

- Jones, J. Barrie (1998). "Piano music for concert hall and salon c. 1830-1900", in The Cambridge Companion to the Piano, ed. David Rowland, pp. 151-175. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521479868

- Lamb, Andrew (1975). "Brahms and Johann Strauss" in The Musical Times vol. 116 no. 1592 (October 1975), pp. 869–871. JSTOR 959201

- Musgrave, Michael (ed.) (1999a). The Cambridge Companion to Brahms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521485814.

- Musgrave, Michael (1999b). "Years of Transition: Brahms and Vienna 1862-1875". In Musgrave (1999a), pp. 31-50.

- Musgrave, Michael (2000). A Brahms Reader. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300068042.

- Schumann, Clara, and Brahms, Johannes, ed. Berthold Lutzmann (1927). Briefe aus den Jahren 1853–1896, two vols. Leipzig. (In German)

- Schumann, Eugenie, tr. Marie Busch (1991). The Schumanns and Johannes Brahms: The Memoirs of Eugenie Schumann. Lawrence, Mass: Music Book Society. ISBN 1-878156-01-2

- Schumann, Robert, tr. and ed. Henry Pleasants (1988). Schumann on Music. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486257487

- Swafford, Jan, (1999). Johannes Brahms: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333725894.

- Swafford, Jan (2001). "Did the Young Brahms Play Piano in Waterfront Bars?". 19th-Century Music. 24 (3): 268–275. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.268. ISSN 0148-2076. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195384833

External links[edit]

Sheet music[edit]

- Free scores by Brahms at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Johannes Brahms in the Open Music Library

- Complete collection of scores at the Brahms Institut in Breitkopf & Härtel or Simrock editions; work details

- Free scores by Smerus/brahms in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

Other links[edit]

- Brahms Institute website, Lübeck Academy of Music

- The Lied and Art Song Texts Page created and maintained by Emily Ezust Texts of the Lieder of Brahms with translations in various languages.

- "What's late about late Brahms?": an article in the TLS by Peter Williams, 7 November 2007

- Brahms at the Piano. Information about the recording made by Thomas Edison in 1889 of Brahms playing part of his Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor.

- "Discovering Brahms". BBC Radio 3.

- Listings of forthcoming live performances of Brahms at Bachtrack