User:SlotOGoldenGoose/sandbox

History[edit]

See also Legal History.

This is a more general overview of the development of the judiciary and judicial systems over the course of history.

Roman judiciary[edit]

See also Roman law and Byzantine Law.

Archaic Roman Law (650-264 BC)[edit]

When Rome first started to exist, law was given by the gods. The most important part was Ius Civile (latin for "civil law"). This consisted of Mos Maiorum (latin for "way of the ancestors") and Leges (latin for "laws"). Mos Maiorum was the rules of conduct based on social norms created over the years by predecessors. In 451-449 BC, the Mos Maiorum was written down in the Twelve Tables[1][2][3]. Leges were rules set by the leaders, first the kings, later the popular assembly during the Republic. In these early years, the legal process consisted of two phases. The first phase, In Iure, was the judicial process. One would go to the head of the judicial system (at first the priests as law was part of religion) who would look at the applicable rules to the case. Parties in the case could be assisted by jurists[4]. Then the second phase would start, the Apud Iudicem. The case would be put before the judges, which were normal Roman citizens in an uneven number. No experience was required as the applicable rules were already selected. They would merely have to judge the case[5].

Pre-Classical Roman Law (264-27 BC)[edit]

The most important change in this period was the shift from priest to praetor as the head of the judicial system. The praetor would also make an edict in which he would declare new laws or principles for the year he was elected. This edict is also known as praetorian law[6][7].

Principate (27 BC - 284 AD)[edit]

The Principate is the first part of the Roman Empire, which started with the reign of Augustus. This time period is also known as the "classical era of Roman Law" In this era, the praetor's edict was now known as edictum perpetuum, which were all the edicts collected in one edict by Hadrian. Also, a new judicial process came up: cognitio extraordinaria (latin for "extraordinary process")[8][9]. This came into being due to the largess of the empire. This process only had one phase, where the case was presented to a professional judge who was a representant of the emperor. Appeal was possible to the immediate superior.

During this time period, legal experts started to come up. They studied the law and were advisors to the emperor. They also were allowed to give legal advise on behalf of the emperor[10].

Dominate (284-565 AD)[edit]

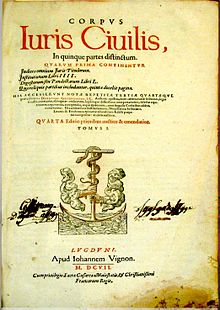

This era is also known as the "post-classical era of roman law". The most important legal event during this era was the Codification by Justinianus: the Corpus Iuris Civilus[11]. This contained all Roman Law. It was both a collection of the work of the legal experts and commentary on it, and a collection of new laws. The Corpus Iuris Civilus consisted of four parts:

- Institutiones: This was an introduction and a summary of roman law.

- Digesta/Pandectae: This was the collection of the edicts.

- Codex: This contained all the laws of the emperors.

- Novellae: This contained all new laws created.

Middle Ages[edit]

See also Church Law

During the late Middle Ages, education started to grow. First education was limited to the monasteries and abbies, but expanded to cathedrals and schools in the city in the 11th century, eventually creating universities[12]. The universities had five faculties: arts, medicine, theology, canon law and Ius Civile, or civil law. Canon law, or ecclesiastical law are laws created by the Pope, head of the Roman Catholic Church. The last form was also called secular law, or Roman law. It was mainly based on the Corpus Iuris Civilis, which had been rediscovered in 1070. Roman law was mainly used for "worldly" affairs, while canon law was used for questions related to the church[13].

The period starting in the 11th century with the discovery of the Corpus Iuris Civilis is also called the Scholastics, which can be divided in the early and late scholastics. It is characterised with the renewed interest in the old texts.

Ius Civile[edit]

Early scholastics (1070 - 1263)[edit]

The rediscovery of the Digesta from the Corpus Iuris Civilis led the university of Bologna to start teaching Roman law[14]. Professors at the university were asked to research the Roman laws and advise the Emperor and the Pope with regards to the old laws. This led to the Glossators to start translating and recreating the Corpus Iuris Civilis and create literature around it:

- Glossae: translations of the old Roman laws

- Summae: summaries

- Brocardica: short sentences that made the old laws easier to remember, a sort of mnemonic

- Quaestio Disputata (sic et non): a dialectic method of seeking the argument and refute it.[15]

Accursius wrote the Glossa Ordinaria in 1263, ending the early scholastics[16].

Late scholastics (1263 - 1453)[edit]

The successors of the Glossators were the Post-Glossators or Commentators. They looked at a subject in a logical and systematic way by writing comments with the texts, treatises and consilia, which are advises given according to the old Roman law[17][18].

Canon Law[edit]

Early Scholastics (1070 - 1234)[edit]

Canon law knows a few forms of laws: the canones, decisions made by Councils, and the decreta, decisions made by the Popes. The monk Gratian, one of the well-known decretists, started to organise all of the church law, which is now known as the Decretum Gratiani, or simply as Decretum. It forms the first part of the collection of six legal texts, which together became known as the Corpus Juris Canonici. It was used by canonists of the Roman Catholic Church until Pentecost (May 19) 1918, when a revised Code of Canon Law (Codex Iuris Canonici) promulgated by Pope Benedict XV on 27 May 1917 obtained legal force[19][20][21].

Late Scholastics (1234 - 1453)[edit]

The Decretalists, like the post-glossators for Ius Civile, started to write treatises, comments and advises with the texts[22][23].

Ius Commune[edit]

Around the 15th century a process of reception and acculturation started with both laws. The final product was known as Ius Commune. It was a combination of canon law, which represented the common norms and principles, and Roman law, which were the actual rules and terms. It meant the creation of more legal texts and books and a more systematic way of going through the legal process[24]. In the new legal process, appeal was possible. The process would be partially inquisitorial, where the judge would actively investigate all the evidence before him, but also partially adversarial, where both parties are responsible for finding the evidence to convince the judge[25].

TO LOOK AT FOR NEXT TIME:

Renaissance

--> Humanism

Enlightenment

See also Age of Enlightenment (theories of government)

--> revolutions, Montesquieu, Locke

In civil law juridictors at present, judges interpret the law to about the same extent as in common law jurisdictions[citation needed] – however it is different from the common law tradition which directly recognizes the limited power to make law. For instance, in France, the jurisprudence constante of the Court of Cassation or the Council of State is equivalent in practice with case law. However, the Louisiana Supreme Court notes the principal difference between the two legal doctrines: a single court decision can provide sufficient foundation for the common law doctrine of stare decisis, however, "a series of adjudicated cases, all in accord, form the basis for jurisprudence constante."[26] Moreover, the Louisiana Court of Appeals has explicitly noted that jurisprudence constante is merely a secondary source of law, which cannot be authoritative and does not rise to the level of stare decisis.[27]

After the French Revolution, lawmakers stopped interpretation of law by judges, and the legislature was the only body permitted to interpret the law; this prohibition was later overturned by the Napoleonic Code.[28]

References[edit]

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 67, 68. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jolowicz, H.F. (1952). Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law. Cambridge. p. 108.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornblower, Antony Spawforth, and Esther Eidinow (eds.) Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.)

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2011). De Oratore. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521593601. OCLC 781329456.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 69–75, 92–93. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Schulz, Fritz (1953). History of Roman Legal Science. Oxford: Oxford University. p. 53.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (3 May 2019). "Roman Legal Procedure". Brittanica.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ du Plessis, Paul J.; Ando, Clifford; Tuori, Kaius, eds. (2016-11-02). "The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society". Oxford Handbooks Online: 153. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198728689.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-872868-9.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 109–113. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Backman, C.R. (2014). Worlds of Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 232–237, 247–252.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 248–252. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 252–254. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Asselt, Willem J. van (Willem Jan van), 1946- (April 2011). Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism. Pleizier, Theo., Rouwendal, P. L. (Pieter Lourens), 1973-, Wisse, Maarten, 1973-. Grand Rapids, Mich. ISBN 9781601783196.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 254–257. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 257–261. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Skyrms, J.F. (1980). "Commentators on The Roman Law". Books at Iowa. no. 32: 3–14. doi:10.17077/0006-7474.1414 – via https://doi.org/10.17077/0006-7474.1414.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|via= - ^ "Benedict XV, Pope". Religion Past and Present. doi:10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_sim_01749. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- ^ Backman, C.R. (2014). Worlds of Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 237–241.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 261–265. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. p. 265. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Izbicki, T.M. (2015). The Eucharist in Medieval Canon Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. xv. ISBN 9781107124417.

- ^ Dębiński, Antoni. (2010). Church and Roman law. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. pp. 82–96. ISBN 9788377020128.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. (25 June 2009). European legal history : a cultural and political perspective. Arriens, Jan. Cambridge, UK. pp. 265–266, 269–274. ISBN 9780521877985. OCLC 299718438.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Willis-Knighton Med. Ctr. v. Caddo-Shreveport Sales & Use Tax Commission, 903 So.2d 1071, at n.17 (La. 2004). (Opinion no. 2004-C-0473)

- ^ Royal v. Cook, 984 So.2d 156 (La. Court of Appeals 2008).

- ^ Cappelletti, Mauro et al. The Italian Legal System, p. 150 (Stanford University Press 1967).