User:Shannon1/Sandbox 5

| Missouri River Big Muddy[1], Mighty Mo, Wide Missouri | |

|---|---|

The Missouri River near Rocheport, Missouri | |

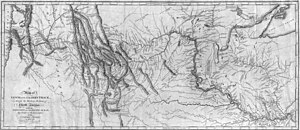

Map of the Missouri River and its tributaries in North America | |

| Etymology | The Missouri tribe, whose name in turn meant "people with wooden canoes"[2] |

| Native name | Pekitanoui[2], Kícpaarukstiʾ[3] Lakota: Mnišoše[4][5] Error {{native name checker}}: parameter value is malformed (help) |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| States | Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri |

| Cities | Great Falls, MT, Bismarck, ND, Pierre, SD, Sioux City, IA, Omaha, NE, Kansas City, KS, Kansas City, MO, St. Louis, MO, St. Joseph, MO |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Hell Roaring Creek–Red Rock River–Beaverhead River–Jefferson River |

| • location | Brower's Spring, Centennial Mountains, Montana |

| • coordinates | 44°33′02″N 111°28′21″W / 44.55056°N 111.47250°W[6][7] |

| • elevation | 9,100 ft (2,800 m) |

| 2nd source | Firehole River–Madison River |

| • location | Madison Lake, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming |

| • coordinates | 44°20′55″N 110°51′53″W / 44.34861°N 110.86472°W[8] |

| • elevation | 8,215 ft (2,504 m) |

| Source confluence | Missouri Headwaters State Park |

| • location | Three Forks |

| • coordinates | 45°55′39″N 111°20′39″W / 45.92750°N 111.34417°W[2] |

| • elevation | 4,042 ft (1,232 m) |

| Mouth | Mississippi River |

• location | Spanish Lake, near St. Louis, Missouri |

• coordinates | 38°48′49″N 90°07′11″W / 38.81361°N 90.11972°W[2] |

• elevation | 404 ft (123 m)[2] |

| Length | 2,322 mi (3,737 km)[9] |

| Basin size | 529,350 sq mi (1,371,000 km2)[10] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Hermann, MO, 97.9 mi (157.6 km) from the mouth |

| • average | 87,890 cu ft/s (2,489 m3/s)[12] |

| • minimum | 602 cu ft/s (17.0 m3/s)[11] |

| • maximum | 750,000 cu ft/s (21,000 m3/s)[13] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Jefferson River, Dearborn River, Sun River, Marias River, Milk River, James River, Big Sioux River, Grand River, Chariton River |

| • right | Gallatin River, Yellowstone River, Little Missouri River, Cheyenne River, White River, Niobrara River, Platte River, Kansas River, Osage River, Gasconade River |

The Missouri River is a major river of the central United States, and is the longest river in North America. Beginning in the Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana, the Missouri flows east and south across the Great Plains for 2,322 miles (3,737 km)[9] before joining the Mississippi River near St. Louis, Missouri. Measured to its furthest headwaters, the Missouri is 2,617 miles (4,212 km) long,[9] with a drainage basin of 529,350 square miles (1,371,000 km2) extending into ten U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. The combined Mississippi–Missouri river system is the fourth longest in the world.

Before the Illinoian glaciation over 100,000 years ago the upper Missouri River likely flowed north into Hudson Bay; as massive ice sheets descended from Canada the river was diverted south across the Great Plains towards the Mississippi. The upper course of the Missouri River roughly marks the edge of the ice sheet at its maximum. Due to its path through thick glacial till and other sedimentary layers, the Missouri has a very high natural sediment load, earning it the nickname, the "Big Muddy". Before the construction of dams and levees, it frequently changed course across its wide floodplain, which supported significant wetland and riparian habitats.

Humans first arrived in the Missouri basin about 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last glacial period as the ice retreated. For thousands of years, the Missouri River has been used by Native Americans as a trade route and a territorial boundary. Native peoples depended on hunting the vast bison (buffalo) herds of the surrounding plains, and used riparian vegetation along the Missouri River as winter forage and material to construct dwellings. European explorers first arrived in the 1600s, with both Spain and France laying claims on the region before the US acquired the Missouri basin via the Louisiana Purchase.

The Missouri River was a key route for the United States' western expansion during the 1800s, starting with the Lewis and Clark Expedition and other explorers, mountain men and fur trappers who mapped the region and blazed trails. Settlers and prospectors headed west en masse beginning in the 1830s, traveling up the river by steamboat before embarking overland by covered wagon, and later the railroad. As settlement encroached on Native American lands, armed conflict broke out; it was not until the 1870s when the U.S. army defeated the last native groups and forced them onto reservations.

Construction of hydroelectric dams began on the Missouri River in the 1890s, providing power to mills and mining settlements. Six much larger dams, comprising the Missouri River Mainstem System, were built between the 1930s and 1960s by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to enhance navigation and control floods. These and hundreds of smaller irrigation, flood control and water supply projects have heavily modified the Missouri River, with considerable economic benefits but at the cost of the natural environment.

Course[edit]

Headwaters[edit]

The Missouri River begins as three major forks in the Rocky Mountains of Montana and Wyoming, which all originate in or near Yellowstone National Park. The longest and westernmost branch originates at Brower's Spring, about 9,000 feet (2,700 m) above sea level in the Centennial Mountains in Beaverhead County, Montana.[14] Brower's Spring feeds into Hell Roaring Creek, which flows west into the Red Rock Lakes and the Red Rock River, which turns northeast at Clark Canyon Reservoir to become the Beaverhead River.[15] At Twin Bridges it is joined by the Big Hole River to form the Jefferson River.[16] The total length from Brower's Spring to the mouth of the Jefferson is 295 miles (475 km).[9]

The Madison River is the middle branch, starting at the confluence of Gibbon River and Firehole River in the western part of Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming.[17] It flows west into Montana, through Hebgen Lake,[18] then turns due north, flowing through a series of ranching valleys and steep canyons.[19] The Madison River is 148 miles (238 km) long, or 183 miles (295 km) including the Gibbon River.[9] The Gallatin River is the easternmost branch, beginning in the Gallatin Range also in Yellowstone National Park.[20] It flows north through a rugged canyon into Montana and emerges into a wide valley near Bozeman.[21] At 115 miles (185 km), it is the shortest of the three forks.[9]

The Jefferson and Madison rivers converge at the appropriately named Three Forks in Missouri Headwaters State Park in Broadwater County, Montana, with the Gallatin joining a short distance downstream. The confluence, at an elevation of 4,042 ft (1,232 m),[22] is located just north of the town of Three Forks.[23] The total drainage area above Three Forks is approximately 14,000 square miles (36,000 km2), about 2.6 percent of the total area of the Missouri basin.[9]

Upper Missouri[edit]

The "Upper Missouri" is defined by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as the Missouri River from Three Forks, Montana to the Gavins Point Dam near Yankton, South Dakota.[24] The total length of the Upper Missouri is 1,526 miles (2,456 km);[9] the drainage basin above Yankton is 279,500 square miles (724,000 km2), or slightly over half of the entire Missouri basin.[25] The upper Missouri basin generally has a colder, drier climate than the lower Missouri, draining parts of the U.S. states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.[19]

From Three Forks, the Missouri River flows north through a wide farming valley between the Big Belt Mountains on the east and the Elkhorn Mountains on the west, both part of the Rocky Mountains.[19] Near the state capital of Helena, it is impounded by Canyon Ferry Dam, which forms Canyon Ferry Lake for flood control and power generation.[26] Below Canyon Ferry Dam are two smaller hydroelectric dams, Hauser Dam and Holter Dam. Between these two dams the Missouri River slices through the northern part of the Big Belt Mountains in a deep gorge known as Gates of the Mountains.[27]

The Missouri River continues north past Craig, where Interstate 15 begins to follow the river.[28] It receives the Dearborn River from the west and emerges from the Rocky Mountains in the Chestnut Valley near Cascade.[29] The 55-mile (89 km), northeast-flowing segment of the Missouri River from Cascade to Great Falls are colloquially known as "Long Pool" due to the slow current and stillness of the water. It receives the Smith River from the southeast at Ulm[30] and the Sun River from the west just above Great Falls.[31]

The Long Pool terminates abruptly at Black Eagle Dam in the city of Great Falls, where the river drops over the Great Falls of the Missouri – five cataracts and many smaller rapids with a total fall of 612 feet (187 m) over a horizontal distance of 10 miles (16 km). Starting upstream, these are Black Eagle Falls, Colter Falls, Rainbow Falls, Crooked Falls and Big Falls (also known as Great Falls or Grand Falls). Since the late 19th century, hydroelectric power stations have greatly altered the appearance and water flow over the falls.

Below Great Falls, the Missouri River flows northeast at the bottom of a canyon cut into the eastern Montana plains. It passes Fort Benton and then receives the Marias River from the west.[32] The river then turns sharply south before heading due east for about 200 miles (320 km) through remote badlands country known as the Missouri Breaks, part of which is protected in Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. Northwest of Winifred, it is joined by the Judith River.[33] Above the confluence of the Musselshell River from the south,[34] the river flows into 134-mile (216 km)-long Fort Peck Lake, the reservoir of Fort Peck Dam, built primarily for flood control.

The Missouri continues flowing east through a much shallower valley below Fort Peck Dam and is joined from the north by the Milk River,[35] which originates in the Rocky Mountains near Glacier National Park and flows for much of its length through Alberta, Canada. This section of the Missouri River, and part of the Milk River above it, are part of Montana's Hi-Line and includes numerous small towns including Wolf Point and Culbertson.[19][36] It is joined from the north by the Poplar River and Big Muddy Creek, both of which extend into Saskatchewan, Canada.[19]

The Missouri River crosses into North Dakota at Buford and shortly after that receives the Yellowstone River, the largest tributary of the upper Missouri, from the south.[37] Originating in Yellowstone National Park not far from the Missouri's own headwaters, the Yellowstone drains an extensive area in southeastern Montana and northern Wyoming.[19] In terms of volume, the Yellowstone is actually larger than the Missouri at their confluence.[38][39]

At Williston, North Dakota the Missouri enters Lake Sakakawea, which lies partly within the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation and is formed by Garrison Dam.[19] Lake Sakakawea is the largest reservoir on the Missouri River by volume, and the third-largest in the United States.[40] Within the reservoir, it is joined by the Little Missouri River, which drains much of western North Dakota including Theodore Roosevelt National Park.[19] Below Garrison Dam, the Missouri River turns south and is joined by the Knife River from the west at Stanton.[41] It continues south to Bismarck, state capital of North Dakota, where it is joined by the Heart River, also from the west.[42]

Entering South Dakota, the river is impounded in the Lake Oahe reservoir, the longest of the mainstem Missouri reservoirs at 231 miles (372 km).[43] In South Dakota, it passes the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Reservations, and receives the Cannonball, Grand and Moreau Rivers, all from the west.[19] At the southeast corner of the Cheyenne River Reservation the Missouri River is joined from the west by the Cheyenne River, which drains the Black Hills region of South Dakota.[19] About 30 miles (48 km) downstream is Oahe Dam and the state capital Pierre, where the Bad River joins from the west.[44]

Below Pierre is Lake Sharpe, formed by Big Bend Dam, and then Lake Francis Case, formed by Fort Randall Dam.[19] The White River joins from the west in Lake Francis Case.[19] Near Fort Randall Dam the Missouri River begins to form the South Dakota–Nebraska boundary[19] and is joined from the south by the Niobrara River, before being impounded by Gavins Point Dam, forming Lewis and Clark Lake.[45]

Lower Missouri[edit]

The Lower Missouri is 796 miles (1,281 km) long,[9] stretching from Gavins Point Dam to the Missouri's mouth at St. Louis. The lower Missouri basin includes parts of Colorado, Iowa, Kansas Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming. Unlike the upper Missouri, the lower Missouri is uninterrupted by dams, due to its use as a shipping channel below Sioux City, Iowa. Its floodplain is much wider and more deeply filled with alluvium, with the low bluffs on either side often several miles apart. The channel of the lower Missouri is naturally meandering, and has been artificially straightened and leveed for much of its length to protect against floods. The most extensively farmed part of the Missouri basin is in the southeast, where the elevation is low and the climate is much wetter than the upper Missouri basin.

A short distance below Gavins Point Dam and Yankton the Missouri is joined from the north by the slow-flowing James River, which drains much of the eastern Dakotas. Continuing east, the Missouri receives the Vermillion River from the north at Vermillion, South Dakota, then begins to form the Nebraska–Iowa boundary at Sioux City, where it receives the Big Sioux River and Floyd River from the north.[46] From there the Missouri turns south, flowing past the Omaha Reservation, and receives the Little Sioux River from the east near Little Sioux, Iowa.[47]

The Missouri flows through Omaha, Nebraska and south of there receives the Platte River from the west.[48] Including the North Platte River, the Platte is the Missouri's longest tributary, extending 1,090 miles (1,750 km) through Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska.[9] Downstream of Nebraska City, Nebraska it flows southeast, forming the Nebraska–Missouri boundary,[19] and a short distance below there it receives the Nishnabotna River from the east.[49] It then receives the Little Nemaha River from the west at Nemaha, Nebraska, the Tarkio River from the east south of Corning, Missouri, and the Big Nemaha River from the west at the Ioway Reservation, below which it begins to form the border of Missouri and Kansas.[19]

The river continues east-southeast, receiving the Wolf River from the southwest and the Nodaway River from the northeast, before turning south at St. Joseph, Missouri. It flows past Atchison and Leavenworth, Kansas, and receives a second tributary called Platte River from the east.[50] It then flows through the middle of Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas, where it is joined from the west by the Kansas River.[51] I-29 parallels the Missouri to the east from Sioux City through Omaha as far as Kansas City.[19] At the Kansas River confluence the Missouri turns east, roughly bisecting the state of Missouri in the last 370 miles (600 km)[9] of its course.[19]

The Missouri is joined by the Fishing River from the north, then receives the Crooked River from the north at Lexington, Missouri.[52] Near Brunswick it receives the Grand River, which drains much of northwestern Missouri and a small portion of southern Iowa, then receives the Chariton and Little Chariton Rivers, also from the north.[19] The river then approaches Boonville, where it receives the Lamine River from the south,[53] and then passes Columbia and the state capital of Jefferson City.[19][54]

Below Jefferson City, the Missouri is joined by the Osage River from the south.[55] The Osage is the largest tributary of the lower Missouri by volume, draining an extensive watershed in central Missouri and eastern Kansas. At Gasconade it is joined from the south by the Gasconade River,[56] and at Hermann it receives the Loutre River from the north.[57] The river continues east, entering the St. Louis metropolitan area. It joins the Mississippi River to the north of St. Louis, on the Missouri–Illinois border near Hartford, Illinois.[58]

Major tributaries[edit]

Over 95 major tributaries and hundreds of smaller streams feed the Missouri River.[59] Most of the Missouri's tributaries flow from west to east, down the incline of the Great Plains; however, some eastern tributaries such as the James, Big Sioux and Grand River systems flow from north to south.[60] The table below lists all the tributaries of the Missouri River more than 500 miles (800 km) long as measured to their farthest source. All data are from the U.S. Geological Survey, unless otherwise noted.

| Major tributaries of the Missouri River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | State (at confluence) | Mouth coordinates |

Length (mainstem)[9] | Length (to farthest source)[9] | Drainage basin[49] | Discharge | Image |

| Milk River | Montana | 48°03′26″N 106°19′07″W / 48.05722°N 106.31861°W[61] | 729 mi (1,174 km) |

771 mi (1,241 km)[n 1] |

23,800 mi2 (61,600 km2)[62] |

659 ft3/s (19 m3/s)[63] |

|

| Yellowstone River | North Dakota | 47°58′42″N 103°58′56″W / 47.97833°N 103.98222°W[64] | 693 mi (1,116 km) |

775 mi (1,248 km)[n 2] |

70,000 mi2 (180,000 km2) |

12,400 ft3/s (351 m3/s)[65] |

|

| Little Missouri River | North Dakota | 47°36′38″N 102°52′24″W / 47.61056°N 102.87333°W[66] | 674 mi (1,085 km) |

674 mi (1,085 km) |

9,550 mi2 (24,800 km2) |

427 ft3/s (12 m3/s)[67] |

|

| Cheyenne River | South Dakota | 44°44′36″N 101°04′05″W / 44.74333°N 101.06806°W[68] | 431 mi (694 km) |

643 mi (1,035 km)[n 3] |

24,300 mi2 (63,000 km2) |

776 ft3/s (22 m3/s)[69] |

|

| White River | South Dakota | 43°42′50″N 99°28′01″W / 43.71389°N 99.46694°W[70] | 580 mi (934 km) |

580 mi (934 km) |

9,870 mi2 (25,600 km2) |

582 ft3/s (16 m3/s) |

|

| Niobrara River | Nebraska | 42°45′58″N 98°02′50″W / 42.76611°N 98.04722°W[71] | 571 mi (919 km) |

571 mi (919 km) |

13,900 mi2 (36,000 km2) |

1,757 ft3/s (50 m3/s)[72] |

|

| James River | South Dakota | 42°52′17″N 97°17′26″W / 42.87139°N 97.29056°W[73] | 775 mi (1,248 km) |

775 mi (1,248 km) |

21,500 mi2 (55,700 km2) |

1,605 ft3/s (45 m3/s)[74] |

|

| Platte River | Nebraska | 41°03′14″N 95°52′53″W / 41.05389°N 95.88139°W[75] | 318 mi (512 km) |

1,093 mi (1,760 km)[n 4] |

84,900 mi2 (220,000 km2) |

7,153 ft3/s (203 m3/s)[76] |

|

| Kansas River | Kansas | 39°06′55″N 94°36′38″W / 39.11528°N 94.61056°W[77] | 173 mi (279 km) |

785 mi (1,264 km)[n 5] |

59,500 mi2 (154,000 km2) |

7,259 ft3/s (207 m3/s) |

|

| Osage River | Missouri | 38°35′49″N 91°56′43″W / 38.59694°N 91.94528°W[78] | 278 mi (448 km) |

537 mi (865 km)[n 6] |

14,800 mi2 (38,300 km2) |

10,360 ft3/s (293 m3/s)[79] |

|

Hydrology[edit]

| Missouri River discharge at selected locations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Location | Average discharge |

Drainage area |

| Toston, MT[80] | 5,089 ft3/s (144 m3/s) | 14,669 mi2 (38,024 km2) |

| Great Falls, MT[81] | 7,343 ft3/s (208 m3/s) | 23,292 mi2 (60,375 km2) |

| Culbertson, MT[82] | 9,985 ft3/s (283 m3/s) | 88,386 mi2 (229,110 km2) |

| Bismarck, ND[83] | 22,480 ft3/s (637 m3/s) | 186,400 mi2 (483,200 km2) |

| Yankton, SD[25] | 26,100 ft3/s (739 m3/s) | 279,500 mi2 (724,500 km2) |

| Omaha, NE[84] | 33,310 ft3/s (943 m3/s) | 322,800 mi2 (836,700 km2) |

| St. Joseph, MO[85] | 46,680 ft3/s (1,322 m3/s) | 426,500 mi2 (1,105,000 km2) |

| Kansas City, MO[86] | 56,040 ft3/s (1,587 m3/s) | 484,100 mi2 (1,255,000 km2) |

| Hermann, MO[12] | 87,890 ft3/s (2,489 m3/s) | 522,500 mi2 (1,354,000 km2) |

As the Missouri drains a predominantly semi-arid region, its discharge is relatively low for a river of its length. Despite having the longest main stem of any river in North America, it ranks only sixth in discharge among US rivers.[87] On average, the Missouri River provides 47 percent of the total flow of the Mississippi at St. Louis, although it drains an area three times as large.[12][88]

At Hermann, Missouri, about 100 miles (160 km) above the mouth, the average flow of the Missouri River between 1958 and 2013 was 87,890 cubic feet per second (2,489 m3/s). The greatest flood on record was 750,000 cubic feet per second (21,000 m3/s) on July 31, 1993, and the lowest daily mean was 6,210 cubic feet per second (176 m3/s) on December 23, 1963.[12] The highest monthly flows are in May and June, and the lowest are in December and January. The majority of water flowing in the Missouri River comes from the lower half of the Missouri basin below Yankton. The average flow at Yankton is 26,100 cubic feet per second (740 m3/s), only a third of the Missouri's total flow at the mouth.[89]

Water levels in the Missouri River experience great seasonal variation. Before the construction of dams, the Missouri flooded twice each year – once in the "April Rise" or "Spring Fresh", with the melting of snow on the Great Plains, followed by the much bigger "June Rise", caused by snowmelt and summer rainstorms in the Rocky Mountains. In some years, the river could increase to as much as ten times its dry season flow.[90][91]

The Missouri's discharge is affected by some 17,200 reservoirs with an aggregate capacity of some 141 million acre-feet (174 km3).[60] About half of this capacity is provided by the six major dams on the main stem of the Missouri.[60] By providing flood control, the reservoirs dramatically reduce peak flows and increase low flows. Reservoir evaporation has reduced the total amount of water flowing through the Missouri River system, with an annual loss of over 3 million acre-feet (3.7 km3) from mainstem reservoirs alone.[60]

Major floods[edit]

Drainage basin[edit]

The Missouri River has a total drainage basin (watershed) of 529,350 square miles (1,371,000 km2) in the US and Canada.[10] About 508,000 square miles (1,320,000 km2) of the basin is in the United States,[49] covering one-sixth of the continental US.[92] The Missouri River basin is roughly bounded by the Rocky Mountains on the west, the Coteau du Missouri (known as the Missouri Coteau in Canada) to the north and northeast, and the Ozark Plateau to the southeast. The Rocky Mountains comprise just over 10 percent of the Missouri basin, and the Ozarks about 2 percent. The remaining 88 percent of the basin consists mostly of plains and lowlands.[60] Elevations in the basin range from just over 400 feet (120 m) at the Missouri's mouth[2] to the 14,293-foot (4,357 m) summit of Mount Lincoln in central Colorado.[93][94]

The Missouri River basin is bordered by many other major North American watersheds.[95] The Rocky Mountains on the west form the Continental Divide, separating the Missouri River basin from the Columbia and Colorado River systems, which both drain to the Pacific Ocean. The Columbia, Missouri and Colorado watersheds meet at Three Waters Mountain in Wyoming's Wind River Range.[96] The endorheic Great Divide Basin lies between the Missouri and Colorado basins in southern Wyoming.[97] To the north the Missouri basin borders the Nelson–Saskatchewan–Red River basin, part of the Hudson Bay drainage.[95] The boundary between the two forms part of the Laurentian Divide. On the east and south, the Missouri basin is bordered by other tributary watersheds of the Mississippi River.[95] These are the Minnesota River and Des Moines River to the east, the White River to the southeast, and the Arkansas River to the south.[95]

The Missouri's drainage basin has highly variable weather and rainfall patterns. Overall, the basin experiences a continental climate with warm, wet summers and harsh, cold winters, with an average of of 8 to 10 inches (200 to 250 mm) of precipitation each year.[60] However, parts of the Rocky Mountains, in Montana, Wyoming and Colorado, as well as lowlands to the southeast in Iowa and Missouri, receive as much as 40 inches (1,000 mm).[60] In the high plains and Rocky Mountains, much of this precipitation falls as winter snow.[60] Although most precipitation falls in winter, the upper Missouri basin is prone to short-lived, intense summer thunderstorms that can result in dangerous flooding, such as the 1972 Black Hills flood in Rapid City, South Dakota.[98] Winter temperatures in Montana, Wyoming and Colorado may drop as low as −60 °F (−51 °C), while summer highs in Kansas and Missouri have reached 120 °F (49 °C) at times.[60]

As of 2010, the total population of the 467 U.S. counties in the Missouri basin was 15.5 million.[99] The largest metropolitan areas, as of the 2010 census, were Denver, Colorado (3.1 million), St. Louis, Missouri (2.9 million), Kansas City, Missouri (2.3 million), and Omaha, Nebraska (900,000).[100] Only Denver is not located on the Missouri River; it is located on the South Platte River, a tributary of the Platte River.[19] Outside of major metro areas, the basin (including the Canadian portion) is rural and often very sparsely populated. Only about 2 percent of the Missouri basin is urbanized.[60]

Geologic history[edit]

The Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana at the headwaters of the Missouri River first rose in the Laramide Orogeny, a mountain-building episode that occurred from around 70 to 45 million years ago (the end of the Mesozoic through the early Cenozoic).[101] This orogeny uplifted Cretaceous rocks along the western side of the Western Interior Seaway, a vast shallow sea that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, and deposited the sediments that now underlie much of the drainage basin of the Missouri River.[102][103][104] This Laramide uplift caused the sea to retreat and laid the framework for a vast drainage system of rivers flowing from the Rocky and Appalachian Mountains, the predecessor of the modern-day Mississippi basin.[105][106][107]

The Missouri and most of its tributaries cross the Great Plains, flowing over or cutting into the Ogallala Group and older mid-Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. The lowest major Cenozoic unit, the White River Formation, was deposited between roughly 35 and 29 million years ago[108][109] and consists of claystone, sandstone, limestone, and conglomerate.[109][110] Channel sandstones and finer-grained overbank deposits of the fluvial[111] Arikaree Group were deposited between 29 and 19 million years ago.[108] The Miocene-age Ogallala and the slightly younger Pliocene-age Broadwater Formation were deposited atop the Arikaree Group, and are formed from material eroded off of the Rocky Mountains during a time of increased generation of topographic relief.[108][112] These formations stretch from the Rocky Mountains nearly to the Iowa border and give the Great Plains much of their gentle but persistent eastward tilt, and also constitute a major aquifer.[113]

Immediately before the Quaternary Ice Age, the Missouri River was likely split into three segments: an upper portion that drained northwards into Hudson Bay,[114][115] and middle and lower sections that flowed eastward down the regional slope.[116] As the Earth plunged into the Ice Age, a pre-Illinoian (or possibly the Illinoian) glaciation diverted the Missouri River southeastwards towards its present confluence with the Mississippi and caused it to integrate into a single river system that cuts across the regional slope.[117] In western Montana, the Missouri River is thought to have once flowed north then east around the Bear Paw Mountains.[citation needed] Sapphires are found in some spots along the river in western Montana.[118][119] Advances of the continental ice sheets diverted the river and its tributaries, causing them to pool up into large temporary lakes such as Glacial Lakes Great Falls, Musselshell and others. As the lakes rose, the water in them often spilled across adjacent local drainage divides, creating now-abandoned channels and coulees including the Shonkin Sag, 100 miles (160 km) long. When the glaciers retreated, the Missouri flowed in a new course along the south side of the Bearpaws, and the lower part of the Milk River tributary took over the original main channel.[120]

The Missouri's nickname, the "Big Muddy", was inspired by its enormous loads of sediment or silt – some of the largest of any North American river.[1][121] In its pre-development state, the river transported some 175 to 320 million short tons (159 to 290 Mt) per year.[122] The construction of dams and levees has drastically reduced this to 20 to 25 million short tons (18 to 23 Mt) in the present day.[123] Much of this sediment is derived from the river's floodplain, also called the meander belt; every time the river changed course, it would erode tons of soil and rocks from its banks. However, damming and channeling the river has kept it from reaching its natural sediment sources along most of its course. Reservoirs along the Missouri trap roughly 36.4 million short tons (33.0 Mt) of sediment each year.[60] Despite this, the river still transports more than half the total silt that empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River Delta is mostly composed of sediment that originated in the Missouri River system.[123][124]

Native Americans[edit]

Archaeological evidence suggests that human beings first inhabited the basin of the Missouri River between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene.[125] At the end of the last glacial period, humans crossed the Bering land bridge from Eurasia to North America, with the Missouri River forming one of the main migration paths as people spread throughout the central and eastern parts of the continent.[citation needed] Most groups that passed through the area eventually settled in the Ohio Valley and the lower Mississippi River Valley, developing into cultures such as the Mound builders; those that stayed along the Missouri became the ancestors of present-day Plains Indians.[126]

No written records from the pre-European contact period exist because they did not yet use writing. According to the writings of European explorers and colonists, the major Native American groups along the Missouri River (from downstream to upstream) included the Otoe, Missouria, Omaha, Ponca, Brulé, Lakota (Teton Sioux), Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Assiniboine, Gros Ventres and Blackfeet.[127] Native people had access to ample food, water, and shelter along the Missouri River, where large riparian areas in the floodplain provided winter forage and attracted game animals.[128]

The Missouri River has been a path of trade and transport, as well as forming territorial boundaries, since ancient times.[citation needed] Most of the native cultures were semi-nomadic, with annual migration between summer and winter camps. The center of Native American wealth and trade lay along the Missouri River near what is now Bismarck, North Dakota.[129] A cluster of walled Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara villages situated on bluffs and islands of the river was home to thousands. It formed a major regional market and trading post, which was later frequented by European explorers and fur traders as well.[130]

Many Native Americans relied on the American bison (commonly called buffalo) as a source of food and clothing, as well as other household items.[131] Before European contact, tens of millions of bison roamed the plains of the Missouri River basin,[132] part of the great bison belt extending from as far north as Alaska south to Mexico east of the Continental Divide.[133] Native Americans periodically set controlled burns on the prairie, clearing space for the new plant growth that the bison preferred.[131]

Following the introduction of horses to the Missouri River basin from feral European-introduced populations, life changed dramatically for many native groups. The use of horses allowed them to travel greater distances, and increased their capability to hunt bison.[134] However, by the mid-1800s, massive over-hunting by Europeans reduced Great Plains bison populations to only a few hundred survivors, cutting off the Native Americans' main source of sustenance.[citation needed] Old World diseases wiped out as much as 90 percent of the Native American population.[citation needed] By the early 1900s, the remaining Native Americans had been forced into reservations, where their descendants live today.[135]

Early European explorers[edit]

In May 1673, the French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette left the settlement of St. Ignace on Lake Huron and traveled down the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers, thinking they led to the Pacific Ocean. In late June, Jolliet and Marquette became the first documented European discoverers of the Missouri River, which according to their journals was in flood.[136] "I never saw anything more terrific," Jolliet wrote, "a tangle of entire trees from the mouth of the Pekistanoui [Missouri] with such impetuosity that one could not attempt to cross it without great danger. The commotion was such that the water was made muddy by it and could not clear itself."[137][138] They recorded Pekitanoui or Pekistanoui as the local name for the Missouri. The party never explored the Missouri beyond its mouth, nor did they linger in the area. Later they learned that the Mississippi drained into the Gulf of Mexico and not the Pacific; the expedition turned back about 440 miles (710 km) short of the Gulf at the confluence of the Arkansas River with the Mississippi.[137]

In 1682, France expanded its territorial claims in North America to include land on the western side of the Mississippi River, which included the lower portion of the Missouri River.[citation needed] However, the Missouri itself remained formally unexplored until Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont commanded an expedition in 1714 that reached at least as far as the mouth of the Platte River.[139] It is unclear exactly how far Bourgmont traveled beyond there; he described the blond-haired Mandans in his journals, so he may have reached as far as their villages in present-day North Dakota.[139]

Later that year, Bourgmont published The Route To Be Taken To Ascend The Missouri River, the first known document to use the name "Missouri River". Many of the names he gave to tributaries, mostly referring to the Native American groups that lived along them, are still in use today.[citation needed] Bourgmont's discoveries eventually found their way to cartographer Guillaume Delisle, who used the information to create a map of the lower Missouri.[140] In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville requested that the French government bestow upon Bourgmont the Cross of St. Louis because of his "outstanding service to France".[140]

Bourgmont had in fact been in trouble with the French colonial authorities since 1706, when he deserted his post as commandant of Fort Detroit after poorly handling an attack by the Ottawa that resulted in thirty-one deaths.[141] However, his reputation was enhanced in 1720 when the Pawnee – who Bourgmont had befriended on his expeditions – massacred the Spanish Villasur expedition on the Missouri River near present-day Columbus, Nebraska, temporarily ending Spanish encroachment on French Louisiana.[142]

Bourgmont established Fort Orleans, the first European settlement of any kind on the Missouri River, near present-day Brunswick, Missouri, in 1723.[citation needed] The following year Bourgmont led an expedition to enlist Comanche support against the Spanish, who continued to show interest in taking over the Missouri.[citation needed] In 1725 Bourgmont brought the chiefs of several Missouri River tribes to visit France. There he was raised to the rank of nobility and did not accompany the chiefs back to North America. Fort Orleans was either abandoned or its small contingent massacred by Native Americans in 1726.[140][143]

The French and Indian War erupted when territorial disputes between France and Great Britain in North America reached a head in 1754.[citation needed] By 1763, France was defeated by the much greater strength of the British army and was forced to cede its Canadian possessions to the English and Louisiana to the Spanish in the Treaty of Paris, amounting to most of its colonial holdings in North America.[144] Initially, the Spanish did not extensively explore the Missouri and let French traders continue their activities under license. However, this ended after news of the British Hudson's Bay Company incursions in the upper Missouri River watershed was brought back following an expedition by Jacques D'Eglise in the early 1790s.[145] In 1795 the Spanish chartered the Company of Discoverers and Explorers of the Missouri, popularly referred to as the "Missouri Company", and offered a reward for the first person to reach the Pacific Ocean via the Missouri.[citation needed] In 1794 and 1795 expeditions led by Jean Baptiste Truteau and Antoine Simon Lecuyer de la Jonchšre did not even make it as far north as the Mandan villages in North Dakota.[146]

The most successful of the Missouri Company expeditions was that of James MacKay and John Evans.[147] After traveling up the Missouri they established Fort Charles about 20 miles (32 km) south of present-day Sioux City as a winter camp in 1795.[citation needed] At the Mandan villages in North Dakota, they expelled several British traders, and while talking to the populace they pinpointed the location of the Yellowstone River, which was called Roche Jaune ("Yellow Rock") by the French.[citation needed] Although MacKay and Evans failed to accomplish their original goal of reaching the Pacific, they created the first accurate map of the Missouri River up to that point.[146][148]

American frontier[edit]

Louisiana Purchase[edit]

In 1795, the young United States and Spain signed Pinckney's Treaty, which recognized American rights to navigate the Mississippi River and store goods for export in New Orleans.[149] Three years later, Spain revoked the treaty and in 1800 secretly returned Louisiana to Napoleonic France in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso.[150] This transfer was so secret that the Spanish continued to administer the territory.[citation needed] In 1801, Spain restored rights to use the Mississippi and New Orleans to the United States.[151]

Fearing that the navigation cutoffs could occur again, President Thomas Jefferson proposed to buy the port of New Orleans from France for $10 million. Instead, faced with a debt crisis, Napoleon offered to sell the entirety of Louisiana, including the Missouri River basin, for $15 million – amounting to less than 3¢ per acre. The deal was signed in 1803, doubling the size of the United States with the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory.[152] In 1803, Jefferson instructed Meriwether Lewis to explore the Missouri and search for a water route to the Pacific Ocean. By then, it was known that the Columbia River system, which drains into the Pacific, had a similar latitude as the headwaters of the Missouri River, and some believed that a connection or short portage existed between the two.[153] Spain balked at the takeover, citing that they had never formally returned Louisiana to the French.[citation needed] Spanish authorities warned Lewis not to take the journey and forbade him from seeing the MacKay and Evans map of the Missouri, although Lewis eventually managed to gain access to it.[154][155]

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began their expedition in 1804 with a party of thirty-three people in three boats.[156] Although they became the first non-native people to travel the entire length of the Missouri River and reach the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia, they found no trace of the Northwest Passage. They also did not succeed in locating the ultimate source of the Missouri River, erroneously believing it to be Horse Prairie Creek, whose confluence with the Red Rock River (the actual source) forms the Beaverhead River. This was due to Lemhi Pass, the path they took over the Continental Divide, being located at the head of Horse Prairie Creek.[157] Nearly a century would pass before surveyor Jacob Brower discovered the true furthest origin of the Missouri River, the place now called Brower's Spring, in 1896.[14]

The maps made by Lewis and Clark, especially those of the upper Missouri and Pacific Northwest region, provided a foundation for future American explorers and colonists. With the help of Sacagawea, they negotiated relations with numerous Native American tribes and wrote extensive reports on the climate, geology, flora and fauna of the region. The expedition also named many geographic features in the upper Missouri basin, such as the five Great Falls of the Missouri and the Jefferson, Madison and Gallatin Rivers.[158]

Fur trade[edit]

As early as the 1700s, fur trappers had explored parts of the Missouri River hoping to find populations of beaver and river otters, the sale of whose pelts drove the North American fur trade. They came from many different places, including Canadian fur companies at Hudson Bay, the Pacific Northwest, and the eastern United States. Initially the Missouri River was not an area of interest, as early explorers had failed to locate significant fur-bearing animal populations.[159] However, by the 19th century the Lewis and Clark expedition generated renewed interest in the region, and trappers and traders followed their route to discover large beaver and otter populations along the Missouri River and its tributaries.[160]

In 1807, Manuel Lisa organized an expedition which would spark significant growth of the fur trade along the upper Missouri. Lisa and his crew traveled up the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, selling manufactured goods to Native Americans in exchange for furs, and established Fort Raymond at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers in southern Montana.[161][162] The fort would serve primarily as a trading post for bartering with the Native Americans for furs.[163] This method was unlike that of the Pacific Northwest fur trade, in which enterprises such as the Hudson's Bay Company directly hired trappers (of both European and Native American descent).[citation needed]

Fort Raymond was later replaced by Fort Lisa at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers near present day Williston, North Dakota. A second fort also called Fort Lisa was built further downriver in Nebraska. In 1809 the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company was founded by Lisa, William Clark, Pierre Choteau and several others.[164][165] In 1828, the American Fur Company founded Fort Union at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers. Fort Union gradually became the main headquarters for the fur trade in the upper Missouri basin.[166]

The fur trade in the early 19th century encompassed streams on both sides of the Rocky Mountains. Trappers of the Hudson's Bay Company, St. Louis Missouri Fur Company, American Fur Company, Rocky Mountain Fur Company, North West Company and other outfits worked thousands of streams in the Missouri watershed as well as the neighboring Columbia, Colorado, Arkansas, and Saskatchewan river systems.[citation needed] During this period, the trappers – including mountain men such as William H. Ashley and Jim Bridger – blazed trails through the wilderness that would later be traveled by westbound settlers. With thousands of beaver pelts requiring transport, a lucrative shipping industry on the Missouri River was born.[167][citation needed]

By the late 1830s, the fur trade was in decline as silk replaced fur as a desirable clothing item. By this time, beaver and otter populations across a large part of the West had been decimated by intense trapping.[citation needed] Furthermore, frequent Native American attacks on trading posts posed a danger for fur company employees.[citation needed] However, in some areas, the fur trade continued well into the 1840s.[168] The fur trade finally disappeared in the Great Plains around 1850, with remaining activity shifting to the Mississippi Valley and central Canada. Despite its quick demise, the fur trade was a crucial factor in opening large areas of the Missouri basin to European settlement.[169]

Western expansion[edit]

The river roughly defined the American frontier in the mid-19th century, beginning downstream from Kansas City, where it takes a sharp eastern turn into the heart of the state of Missouri, an area known as the Boonslick.[citation needed] As the first area settled by Europeans along the river, it was largely populated by slave-owning southerners following the Boone's Lick Road.[citation needed] Later, the major trails for the opening of the American West all started on the river, including the California, Mormon, Oregon, and Santa Fe trails.[citation needed] The first westward leg of the Pony Express was a ferry across the Missouri at St. Joseph, Missouri.[citation needed] Similarly, most emigrants arrived at the eastern terminus of the First Transcontinental Railroad via a ferry ride across the Missouri between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha.[170][171] The Hannibal Bridge became the first bridge to cross the Missouri River in 1869, and was a major factor in Kansas City's growth into the largest city on the Missouri above St. Louis.[172]

More than 500,000 people traveled up the Missouri River to embark on their journeys west from the 1830s to the 1860s.[citation needed] Many were farmers settling the Great Plains under the Homestead Act, and starting in 1848 the California Gold Rush caused a surge of prospectors heading west.[173] Most settlers traveled by boat up the Missouri River to Omaha, where they set out by land along the Platte River, which provides a natural corridor across the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains, albeit not a navigable one.[citation needed] Robert Stuart's expedition in 1812–1813 had found the shallow, braided Platte impractical to navigate even by canoes.[citation needed] Pioneers described the Platte as "a mile wide and an inch deep" and "the most magnificent and useless of rivers".[174] The river's importance was mainly as a water source and hunting ground. Covered wagons, popularly referred to as prairie schooners, were the primary means of transport until the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869.[175]

After the California gold rush, gold strikes in Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, and northern Utah drew even more people west.[citation needed] Most transport to and from the gold fields was done through the Missouri and Kansas Rivers, as well as the Snake River in western Wyoming and the Bear River in Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming.[176] About 80 percent of passengers and freight between Missouri and Montana were transported by boat – a journey that took 150 days in the upstream direction.[citation needed] The route to Colorado traveled up the Kansas River and its tributary the Republican River, but still required significant overland travel before reaching Denver.[citation needed]

During the 1850s and 1860s the Missouri River was the scene of conflict leading up to the American Civil War, as controversy erupted among Kansas settlers over whether the new territory should allow or ban slavery. Pro-slavery forces from Missouri would cross the river into Kansas and spark mayhem during Bleeding Kansas.[citation needed] After the Civil War broke out, some people in Missouri supported joining the Confederacy, although Missouri initially remained a neutral state. A major turning point in the war was the 1861 Battle of Boonville, in which the Union seized control of transport on the Missouri River, effectively ending the secession movement in Missouri.[177]

During this time, farmers settling on the Great Plains came into direct conflict with Native American tribes. After a number of raids and massacres on both sides, the US government began to sign treaties reserving land for Native Americans, but soon broke them, leading to more conflicts.[citation needed] During the 19th century, the Plains Indians – now armed with horses and rifles – fought the U.S. army in more than 1,000 battles.[178][179] Settlers clashed with Native Americans along the Bozeman Trail,[180] leading to Red Cloud's War (or the Bozeman War), in which the Lakota and Cheyenne defeated the U.S. army.[181] In 1868, the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed, which "guaranteed" the use of the Black Hills, Powder River Country and other areas of the upper Missouri basin to Native Americans.[182]

In the 1870s, prospectors discovered gold in the Black Hills and were then attacked by Native Americans, leading to the Great Sioux War of 1876.[182] The U.S. government sided with the miners despite the 1868 treaty having reserved those lands for Native Americans.[citation needed] Several battles were fought including the Battle of the Little Bighorn, in which Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho forces defeated the US Cavalry regiment led by George Armstrong Custer. However, the Native Americans were already considerably weakened by the destruction of buffalo populations and loss of their traditional lands, and surrendered in 1877 (although some fled to Canada before turning themselves in a few years later).[citation needed] The Black Hills were opened to mining and settlement, and the Native Americans were relocated to reservations.[183]

Steamboats[edit]

Boat travel on the Missouri started with the wood-framed canoes and bull boats of the Native Americans, which were used for thousands of years before the introduction of larger craft to the river by Europeans.[184] The first steamboat on the Missouri was the Independence, which started running between St. Louis and Keytesville, Missouri around 1819.[185] By the 1830s, steamboats were regularly carrying freight and mail between Kansas City and St. Louis, and some traveled even farther upstream. The Western Engineer and the Yellowstone were among the first steamboats that reached Montana.[184][186]

During the early 19th century, at the height of the fur trade, steamboats and keelboats traveled nearly the whole length of the Missouri below Fort Benton, Montana, carrying beaver pelts and buffalo hides from the hunting grounds to market.[187] The Missouri River mackinaw, which specialized in carrying furs, was also developed during this time. Since these vessels could only travel downriver, they were dismantled and sold for lumber upon their arrival at St. Louis.[184]

River traffic increased through the 1850s with numerous vessels carrying westbound settlers, traders and miners; most plied the route from St. Louis or Independence to Omaha.[citation needed] In 1858, more than 130 steamboats were operating full-time on the Missouri.[188] Many of these boats had been built on the Ohio River before being transferred to the Missouri. Side-wheeler steamboats were favored over the large sternwheelers used on the Mississippi and Ohio because of their maneuverability and shallower draft.[187] Although Fort Benton was the head of navigation for most boats, some vessels such as the Rose of Helena operated upstream of Great Falls as far as Helena, Montana.[189]

Before dams and levees were built to control the flow of the Missouri River, the seasonal variations in water level and the constantly shifting channel made navigation difficult and dangerous. At least 300 steamboats were wrecked on the Missouri during the 19th century, when the average lifespan of a Missouri River boat was only four years.[188] The connection of the Transcontinental Railroad to St. Louis, and the development of the Northern Pacific Railroad farther north, spelled the end of steamboat commerce on the Missouri. By the 1890s, the steamboat era was but a memory. Transport of agricultural and mining products by barge, however, saw a major revival in the early twentieth century.[190][191]

Dams on the Missouri River[edit]

Hydroelectricity[edit]

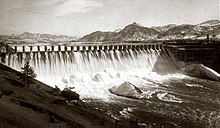

The first dams built on the Missouri River were relatively small structures built to generate hydroelectric power. Between 1890 and 1940, five hydroelectric dams were built in on the Great Falls of the Missouri in and around Great Falls, Montana. The first was Black Eagle Dam, built in 1891 on Black Eagle Falls, was the first dam of the Missouri.[192] Replaced in 1926 with a more modern structure, the dam was little more than a low weir atop Black Eagle Falls, diverting water into the Black Eagle power plant.[193] The largest of the five dams, Ryan Dam (originally named Volta Dam), was built in 1913 on top of the Great Falls' largest drop, 87-foot (27 m) Big Falls.[194]

At the same time, the Montana Power Company constructed dams on the Missouri River below Helena. A small run-of-the river structure completed in 1898 near the present site of Canyon Ferry Dam became the second dam to be built on the Missouri. It generated 7.5 megawatts of electricity for the city of Helena.[195] The steel Hauser Dam was finished in 1907 downstream of Canyon Ferry. It failed in 1908 due to faulty design, causing catastrophic flooding all the way downstream past Craig. At Great Falls, the Black Eagle Dam was dynamited to save nearby factories from flooding.[196] The present-day Hauser Dam was built to a much stronger concrete gravity design in 1910.[197][198]

Holter Dam, about 45 miles (72 km) downstream of Helena, was the third hydroelectric dam built on this stretch of the Missouri River.[199] When completed in 1918 by the Montana Power Company and the United Missouri River Power Company, its reservoir flooded the Gates of the Mountains, a limestone canyon which Meriwether Lewis described as "the most remarkable clifts [sic] that we have yet seen… the tow[er]ing and projecting rocks in many places seem ready to tumble on us."[200] In 1949, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) began construction on the present-day Canyon Ferry Dam to provide flood control to the Great Falls area. By 1954, the rising waters of Canyon Ferry Lake submerged the old dam, whose powerhouse still stands underwater about 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) upstream of the modern dam.[201]

Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program[edit]

The Missouri River caused many major floods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably in 1844, 1881, and 1926–1927.[202] In 1940, as part of the, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) completed Fort Peck Dam in Montana for the primary purpose of flood control.[citation needed] Construction of this New Deal project provided jobs for more than 50,000 workers during the Great Depression.[203] However, Fort Peck only controls runoff from 11 percent of the Missouri River basin,[citation needed] and its limitations were made clear in the flood of 1943, which caused major damage in Omaha and Kansas City. Industrial plants were flooded, delaying shipments of military supplies for World War II.[202][204]

In response to flooding on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1944, authorizing the construction of many more dams on the Missouri.[205][206] A major part of the 1944 act was the Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program (Pick–Sloan Plan), which was actually a compromise between the USACE and the USBR, the two major federal agencies involved in western water development.[207][citation needed] The USACE favored the "Pick plan", with an emphasis on flood control and navigation, and would require several large storage dams along the main stem of the Missouri. The USBR supported the "Sloan plan", which focused mainly on irrigation and hydroelectricity, and proposed about 85 smaller dams on the Missouri's tributaries.[208][209] After a political stalemate, the federal government decided to essentially combine both plans, with some of the less economically viable projects, such as dams on the Yellowstone River, omitted.[citation needed] In part because of this decision, the Yellowstone is now the longest free-flowing river in the contiguous United States.[210]

The Pick-Sloan program initially authorized $1.9 billion to construct 316 separate water projects, including 112 dams.[211] In the 1950s, construction commenced on the five mainstem dams – Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall and Gavins Point – proposed under the Pick-Sloan Plan.[208] Along with Fort Peck, which was integrated as a unit of the Pick-Sloan Plan in the 1940s, these dams now form what is known as the Missouri River Mainstem System.[212] The Garrison Dam as originally proposed would have been much smaller than its current size,[213] but was greatly increased in size to replace the storage that would have otherwise been provided by the canceled Yellowstone dams.[citation needed]

The flooding of lands along the Missouri River heavily impacted Native American groups whose reservations included fertile bottomlands and floodplains, especially in the arid Dakotas where it was some of the only good farmland they had. These consequences were pronounced in North Dakota's Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, where 150,000 acres (61,000 ha) of land was taken by the construction of Garrison Dam. The Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara/Sanish tribes sued the federal government on the basis of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie which provided that reservation land could not be taken without the consent of both the tribes and Congress. After a lengthy legal battle the tribes were coerced in 1947 to accept a $5.1 million settlement for the land, just $33 per acre. In 1949 this was increased to $12.6 million. The tribes were even denied the right to use the reservoir shore "for grazing, hunting, fishing, and other purposes,"[214][215] although these restrictions were later lifted.[citation needed]

Mainstem System[edit]

The six reservoirs of the Mainstem System hold up to 73.4 million acre-feet (90.5 km3) in total, more than three years' worth of the river's flow at Gavins Point Dam.[60] Fort Peck, Garrison and Oahe, are among the largest dams in the world by volume; their sprawling reservoirs also rank within the biggest in the United States.[216] Together, they form the largest reservoir system in the United States and one of the largest in North America.[217] The primary purpose of the Mainstem System is to ensure a sufficient water flow in the lower Missouri for navigation, with a minimum safe level of around 35,000 cubic feet per second (990 m3/s).[218] This also benefits the various water users along the Missouri River. About 3.1 million people receive their water supply directly from the river, which also provides water for irrigation, industry, and coolant for 18 thermal power stations.[218] Although the dams are not necessary for the water supply, river regulation provides significant cost benefits to water suppliers amounting to more than $500 million in 1994.[218]

The Mainstem System provides 16.3 million acre-feet (20.1 km3) of flood-control space to be made available on January 1 of every year,[212][citation needed] and provides flood protection to about 2 million acres (810,000 ha) of land along the river.[60] As of 2006, the six dams had prevented a cumulative $24.8 billion of flood damage, exceeding the entire initial cost of building the dams.[60] However, because the dams only control the upper half of the river, their impact on the river flow becomes more limited with increasing distance downstream. In 1993, the dams prevented about $4.4 billion of damage, but a total of $12 billion of damage was incurred along the lower Missouri.[60]

Hydropower stations at the six dams have a combined capacity of over 2,500 megawatts, generating 9.3 billion KWh annually.[219] Power production is considered secondary to other requirements such as navigation and flood control, so the hydropower potential along the Missouri (namely peaking power production) is not maximized.[218]

Economic use[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

The major economic activity in the Missouri River basin is agriculture; about 95 percent of land in the US part of the basin is used for food production. There are 104 million acres (420,000 km2) of cropland in the Missouri River basin, or about 32 percent of the total area. Most cropland in the basin is in eastern states such as Nebraska and Iowa.[60] A further 180 million acres (730,000 km2) of land (more than half of the Missouri basin) are devoted to grazing, primarily for cattle. The majority of this is located in the western half of the basin.[60] About 28 million acres (110,000 km2) or 9 percent of the basin is forest and woodland, much of which is used for grazing and timber production.[60]

Only 7.4 million acres (30,000 km2) of farmland in the Missouri basin are irrigated,[60] a low proportion compared to many other regions of the American West.[citation needed] As settlers moved to the higher, more arid states such as Montana and Wyoming they had to abandon the riparian water rights system typical of the eastern US, and adopt the prior appropriation ("first in time, first in right") doctrine instead, although some Missouri Basin states such as the Dakotas followed a mixed system until the 1960s, when riparian rights were finally done away with.[232]

The key consequence of the prior-appropriation system was that farmers had to be able to use their water in order to keep their rights to it.[232] The Missouri River and its tributaries have great seasonal variation in water flow, so large reservoirs were needed to ensure a reliable water supply. Because reservoir construction was beyond the abilities of most small farmers, the federal government established the Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) in 1902.[232] Indeed, some of the earliest reclamation projects took place in the Missouri basin, including the Belle Fourche Project in South Dakota,[233] the North Platte Project (Pathfinder Dam) in Wyoming and Nebraska,[234] and the Shoshone Project (Buffalo Bill Dam) in Wyoming.[235]

In states with a "sub-humid" climate like the Dakotas, there was not enough rainfall to support most crops without irrigation, yet irrigation was largely impractical due to unfavorable topography and insufficient surface water supply. Although the Missouri River crosses the region, it flows at the bottom of a deep valley, far out of reach of the surrounding plains. As early as the 1890s, the federal government investigated the possibility of diverting water from the main stem of the Missouri, which would require a canal system hundreds of miles long.[236]

After the Missouri mainstem dams were built in the 1950s and 1960s, the possibility of main-stem Missouri irrigation projects were again explored, though these efforts were not successful. The Garrison Diversion Project, which would irrigate 1 million acres (400,000 ha), and the Oahe Diversion Project, at nearly 500,000 acres (200,000 ha), were the biggest proposals.[237] A major purpose of the Garrison project was to compensate for farmland lost on the Fort Berthold reservation due to the construction of Garrison Dam.[237] Although the projects enjoyed broad political support in the Dakotas, they were opposed by farmers who felt the projects were not necessary, and by environmentalists who feared the destruction of wetland and prairie ecosystems.[237] In addition, much of the land to be served by the project was found to be unsuitable for irrigation.[238]

Shipping[edit]

"[Missouri River shipping] never achieved its expectations. Even under the very best of circumstances, it was never a huge industry."

~Richard Opper, former Missouri River Basin Association executive director[239]

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Missouri River has been extensively engineered to create a navigation channel for barges; about 32 percent of the river has been artificially straightened in some way.[10] In 1912, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was authorized to maintain the Missouri to a depth of six feet (1.8 m) from the Port of Kansas City to the mouth, a distance of 368 miles (592 km).[citation needed] This was accomplished by constructing levees and wing dams to direct the river's flow into a straight, narrow channel and prevent sediment build-up. In 1925, the USACE began widening the river's navigation channel to 200 feet (61 m); two years later, they began dredging a deep-water channel from Kansas City to Sioux City, Iowa. These modifications have reduced the river's length from some 2,540 miles (4,090 km) in the late 19th century to 2,341 miles (3,767 km) in the present day.[240][241][citation needed]

Construction of the six Mainstem System dams was a crucial step in improving navigation, by storing water to maintain a dependable flow during droughts.[242] However, high and low water cycles of the Missouri – notably the protracted early-21st-century drought in the Missouri River basin[243] and historic floods in 1993[244] and 2011[245] – are difficult for even the massive Mainstem System reservoirs to control.[245]

In 1945, the USACE began the Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project, enlarging the navigation channel to a width of 300 feet (91 m) and a depth of nine feet (2.7 m). The 735-mile (1,183 km) navigation channel from Sioux City to St. Louis was opened by building rock dikes to direct the river's flow and scour out sediments, sealing and cutting off meanders and side channels, and dredging the riverbed.[246] Despite all these works, the channel still requires frequent maintenance. In 2006, several U.S. Coast Guard boats ran aground in the Missouri River because the navigation channel had been silted up.[247] The USACE was blamed for failing to maintain the channel to the minimum depth.[248]

In 1929, the Missouri River Navigation Commission estimated the total amount of goods shipped on the river annually at 15 million tons (13.6 million metric tons), a level that it deemed to justify developing a shipping channel. However, boat traffic steadily declined through the 20th century; shipments of commodities including produce, manufactured items, lumber, and oil averaged only 683,000 tons (616,000 t) per year from 1994 to 2006.[249] This was due not only to agricultural production not meeting projections, but to competition from railroads.[218]

By tonnage of transported material, Missouri is by far the largest user of the river accounting for 83 percent of river traffic, while Kansas accounts 12 percent, Nebraska 3 percent and Iowa 2 percent. Almost all of the barge traffic on the Missouri River ships sand and gravel dredged from the lower 500 miles (800 km) of the river; the channel above St. Joseph sees little to no use by commercial vessels.[249]

The Lower Missouri River has no hydroelectric dams or locks but it has numerous partial barriers, called wing dams, that enable barge traffic by directing the flow of the river into a 200-foot-wide (61 m), 12-foot-deep (3.7 m) channel. These wing dams have been put in place by and are maintained by the USACE, and there are no plans to construct any locks to replace these wing dams on the Missouri River.[250][citation needed]

Environment and ecology[edit]

Historically, the floodplain of the Missouri River covered more than 1.5 million acres (610,000 ha).[citation needed] Although it has been heavily modified by agriculture, the Missouri valley continues to support a wide variety of plant and animal species. Biodiversity generally increases going downstream from the cold alpine headwaters in Montana to the temperate, wet climate of Missouri. The river's riparian zone consists primarily of cottonwoods, willows and sycamores, with several other types of trees such as maple and ash.[251] Average tree height generally increases farther from the riverbanks for a limited distance, as land adjacent to the river is vulnerable to soil erosion during floods.

About 300 species of birds are found along the Missouri and its tributaries,[251] notably the vast migratory Sandhill crane population along the Platte River. There are about 150 species of fish in the Missouri River,[252] including endangered species such as the pallid sturgeon. Several mammal species also inhabit the floodplain zone, such as mink, river otter, beaver, muskrat, and raccoon.[253] Because of its large sediment concentrations, the Missouri does not support many aquatic invertebrates.[251]

The World Wide Fund For Nature divides the Missouri River watershed into three freshwater ecoregions: the Upper Missouri, Lower Missouri and Central Prairie. The Upper Missouri, roughly encompassing the area within Montana, Wyoming, southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, and North Dakota, comprises mainly semiarid shrub-steppe grasslands with sparse biodiversity because of Ice Age glaciations. There are no known endemic species within the region. Except for the headwaters in the Rockies, much of this area experiences low precipitation.[254] Prairie potholes, small lakes and wetlands formed in glacial depressions ("kettles"), are found north and east of the Missouri River in Montana and the Dakotas, and provide a significant source of fresh water for migratory birds and other wildlife on the otherwise arid high plains.

The Middle Missouri ecoregion, extending through Colorado, southwestern Minnesota, northern Kansas, Nebraska, and parts of Wyoming and Iowa, has generally greater rainfall, and is characterized by grasslands in the west transitioning to temperate forest in the east. Plant life is more diverse in the Middle Missouri, which is also home to about twice as many animal species.[255] The Sandhills along the Niobrara and North Platte rivers in Nebraska are one of the largest grass-covered sand dune formation in the world, and are one of the few relatively intact prairie ecosystems remaining in this part of the Missouri basin, with 670 species of native plants.[256][257] The Ogallala aquifer, which underlies the Sandhills region and stretches south past Colorado and Kansas, is an important source of water for lakes and wet meadows as well as for irrigation in the southern Missouri basin states.[256]

The Central Prairie ecoregion is situated on the lower part of the Missouri, encompassing all or parts of Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. Despite large seasonal temperature fluctuations, this region has the greatest diversity of plants and animals of the three. Thirteen species of crayfish are endemic to the lower Missouri.[258]

Human impacts[edit]

Since the beginning of river commerce and industrial development in the 1800s, the Missouri has been polluted and its channel heavily modified by human activity. Much of the river's floodplain habitat has been replaced by farmland, with the river constrained to a narrow channel between levees. Urban encroachment into the floodplain has led to increasing amounts of people and infrastructure within high-risk areas.

Fertilizer runoff, which causes elevated levels of nitrogen and other nutrients, is a major problem along the Missouri River, especially in Iowa and Missouri. This form of pollution also heavily affects the upper Mississippi, Illinois and Ohio Rivers. Low oxygen levels in rivers and the vast Gulf of Mexico dead zone at the end of the Mississippi Delta are both results of high nutrient concentrations in the Missouri and other tributaries of the Mississippi.[259][260]

Channelization of the lower Missouri has made the river narrower, deeper and less suitable for native species. Dams have significantly reduced the volume of sediment transported downstream by the river, precluding the formation of sandbars, side channels and backwaters that native species were well adapted to.[261] By the early 21st century, heavy declines native bird and fish species prompted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to issue a biological opinion recommending restoration of habitat along the Missouri River.[262]

Because of low use in parts of the shipping channel, especially upstream of Omaha,[218] some of the levees, dikes, and wing dams that constrict the river's flow have been removed or are under consideration for removal.[261][263] Since the 1990s, the federal government has been acquiring tens of thousands of acres of land in high-risk flood zones for restoration. The Big Muddy National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, established in 1994, has restored more than 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) along the river with plans to expand to 60,000 acres (24,000 ha). Other restoration areas along the Missouri River include Nebraska's Boyer Chute National Wildlife Refuge and Missouri's Squaw Creek National Wildlife Refuge.[264]

However, the removal of some bank stabilization structures has re-mobilized trapped sediments polluted by agriculture and urban waste, prompting concerns of elevated nutrient and chemical levels in not only the Missouri River, but the Mississippi River, the Mississippi Delta and the Gulf of Mexico.[citation needed] A 2010 National Research Council report assessed the roles of sediment in the Missouri River, evaluating current habitat restoration strategies and alternative ways to manage sediment.[265] The report found that a better understanding of sediment processes in the Missouri River, including the creation of a "sediment budget" – an accounting of sediment transport, erosion, and deposition volumes for the length of the Missouri River – would provide a foundation for projects to improve water quality standards and protect endangered species.[266]

Tourism and recreation[edit]

With over 1,500 sq mi (3,900 km2) of open water, the six reservoirs of the Missouri River Mainstem System provide some of the main recreational areas within the basin. Visitation has increased from 10 million visitor-hours in the mid-1960s to over 60 million visitor-hours in 1990.[267] Development of visitor facilities was spurred by the Federal Water Project Recreation Act of 1965, which required the USACE to build and maintain boat ramps, campgrounds and other public facilities along major reservoirs.[60] Recreational use of Missouri River reservoirs is estimated to contribute $85–100 million to the regional economy each year.[268]

The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, some 3,700 miles (6,000 km) long, follows nearly the entire Missouri River from its mouth to its source, retracing the route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Extending from Wood River, Illinois, in the east, to Astoria, Oregon, in the west, it also follows portions of the Mississippi and Columbia Rivers. The trail, which spans through eleven U.S. states, is maintained by various federal and state government agencies; it passes through some 100 historic sites, notably archaeological locations including the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.[269][270]

Parts of the river itself are designated for recreational or preservational use. The Missouri National Recreational River consists of portions of the Missouri downstream from Fort Randall and Gavins Point Dams that total 98 miles (158 km).[271][272] These reaches exhibit islands, meanders, sandbars, underwater rocks, riffles, snags, and other once-common features of the lower river that have now disappeared under reservoirs or have been destroyed by channeling. About forty-five steamboat wrecks are scattered along these reaches of the river.[273][274]

Downstream from Great Falls, Montana, about 149 miles (240 km) of the river course through a rugged series of canyons and badlands known as the Missouri Breaks. This part of the river, designated a U.S. National Wild and Scenic River in 1976, flows within the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument, a 375,000-acre (1,520 km2) preserve comprising steep cliffs, deep gorges, arid plains, badlands, archaeological sites, and whitewater rapids on the Missouri itself. The preserve includes a wide variety of plant and animal life; recreational activities include boating, rafting, hiking and wildlife observation.[275][276]

In north-central Montana, some 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) along over 125 miles (201 km) of the Missouri River, centering on Fort Peck Lake, comprise the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge.[277] The wildlife refuge consists of a native northern Great Plains ecosystem that has not been heavily affected by human development, except for the construction of Fort Peck Dam. Although there are few designated trails, the whole preserve is open to hiking and camping.[278]

Many U.S. national parks, such as Glacier National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, Yellowstone National Park and Badlands National Park are, at least partially, in the watershed. Parts of other rivers in the basin are set aside for preservation and recreational use – notably the Niobrara National Scenic River, which is a 76-mile (122 km) protected stretch of the Niobrara River, one of the Missouri's longest tributaries.[279] The Missouri flows through or past many National Historic Landmarks, which include Three Forks of the Missouri,[280] Fort Benton, Montana,[281] Big Hidatsa Village Site,[282] Fort Atkinson, Nebraska[283] and Arrow Rock Historic District.[284]

See also[edit]

- Across the Wide Missouri (book)

- List of longest main-stem rivers in the United States

- List of crossings of the Missouri River

- List of populated places along the Missouri River

- Montana Stream Access Law

- Montana Wilderness Association

- Sacagawea

- Arabia Steamboat Museum

- Container on barge

Notes[edit]

- ^ Measured to the head of the South Fork Milk River.

- ^ Measured to the head of the Wind–Bighorn River tributary.

- ^ Measured to the head of the Belle Fourche River tributary.

- ^ Measured to the head of the North Platte River and Grizzly Creek.

- ^ Measured to the head of the Republican River and Arikaree River.

- ^ Measured to the head of the Marais des Cygnes River and Elm Creek.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Spotlight on the Big Muddy" (PDF). Missouri Stream Team. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Missouri River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1980-10-24. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ "AISRI Dictionary Database Search--prototype version. "River", Southband Pawnee". American Indian Studies Research Institute. Retrieved 2012-05-26.