User:SchroCat/littertray

REMEMBER ALTS

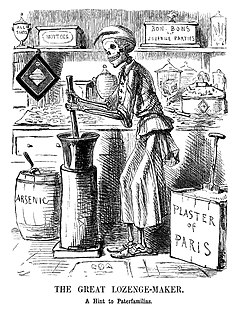

Cartoon in Punch, November 1858 | |

| Date | 30 October 1858 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bradford, England |

| Cause | Arsenic poisoning |

| Casualties | |

| 200+ | |

| Deaths | 20 |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In nunc lacus, efficitur non dapibus nec, iaculis in metus. Suspendisse egestas semper nibh aliquet sodales. Aenean in lobortis tellus, a faucibus tortor. Proin imperdiet non augue sed ultricies. Fusce fermentum, dui sed tincidunt sollicitudin, mauris orci laoreet nulla, eget pretium velit elit eu tellus. Maecenas augue urna, tempus vitae magna id, ultricies placerat tellus. Fusce tristique ex diam, id imperdiet quam egestas interdum. Aliquam placerat eleifend magna, eget ullamcorper tellus pharetra at. Donec consequat risus vitae purus tincidunt varius. Nam pellentesque id dui a convallis. Morbi sit amet lectus tortor. In sit amet tincidunt nibh, ac rutrum tellus. Duis tincidunt ac est ut tristique. In justo nisl, mattis id fringilla at, scelerisque ut erat.

Fusce interdum turpis in odio posuere, venenatis viverra tortor posuere. Sed lacus lorem, finibus a mattis in, congue ut justo. Phasellus luctus mi vitae ligula tempus varius. Donec dignissim nibh in est lacinia, vel accumsan diam venenatis. Praesent porttitor massa vitae quam feugiat finibus. Phasellus nec sagittis nisi. Nulla tempus dignissim leo et hendrerit. Aenean ipsum nibh, pulvinar non sem at, posuere aliquam leo. Duis congue auctor urna et lacinia.

Curabitur cursus et justo non bibendum. Aenean ultrices mollis dolor eu consectetur. Ut placerat nibh arcu. Praesent ornare volutpat augue nec accumsan. Aenean ac finibus tellus. Nam laoreet, massa sed facilisis scelerisque, sapien lectus pulvinar lectus, at tincidunt justo ex et arcu. In in maximus ante. Quisque tortor massa, egestas non est a, congue ultrices elit. Vivamus volutpat sollicitudin neque vel hendrerit. Nullam dictum maximus sapien, sit amet porttitor sem. Sed eu facilisis leo, in fermentum mauris. Proin non ante in lectus facilisis rutrum. Vestibulum tincidunt ante non arcu lacinia, ac tempor ex eleifend.

Background[edit]

The adulteration of food had been practiced in the UK since before the middle ages, but from 1800, with increasing urbanisation and the rise in shop-purchased food, adulterants became a growing problem.[1] The adulteration fell into three categories: harmless additions, such as chicory, adding flour to mustard and watering down milk; the addition of indigestible ingredients, including introducing alum, gypsum or chalk into white bread or tree or shrub leaves into tea leaves; and toxic additions, such as salts of copper and red lead glaze used as colourants, cheese with mercury salts, and the use of arsenic, sulfuric acid and nitric acid.[2]

The chemist Arthur Hill Hassall was prominent in the field of food analysis and the first person to systematically study food through a microscope to establish the level of adulteration. Between 1850 and 1850 he examined 3,000 samples of food and found 65 per cent of them contained adulterants.[3] Those adulterating foodstuff used nicknames to hide the practice. These included "daff", "duck", "duff", "derby", "multum", "flash" and "stuff".[4][5] One local name used in Bradford was "daft".[5] Cost was the reason adulterants were used. Sugar, for example, cost 6½d per pound; the adulterant cost ½d per pound.[6][a]

In the Victorian era, arsenic was an ingredient in several household products, including medicines (for external and internal use), candles, wallpaper, soft furnishings and colourants for foods.[8] It was also used as a poison for murder. The extent of the arsenic-related deaths was such that legislation in the form of the Arsenic Act 1851 was introduced. It was the first piece of UK legislation to attempt to control the sale of a poisonous substance.[9] It stated that arsenic should only be sold to adults, the sale recorded in a book—signed by both seller and buyer—and that there should be a witness to the sale of the buyer was unknown to the seller. Any arsenic not to be used for medicinal purposes was to be coloured with soot or indigo to differentiate it from other white powders on sale.[5][10] There was no restriction on who could sell arsenic; no licence was required and any trader was able to sell it as long as they kept a record of the sale.[5]

Although the Act controlled the method of sale, it did not bring an end to arsenic-related problems or the widespread use of arsenic in household goods. In 1860 an article in The Lancet asked:

How to convict of arsenical poisoning when ladies use arsenical cosmetics; when confectioners sell arsenical sweetmeats; when paperhangers clothe our walls with arsenical hangings, and impregnate all the air with fine arsenical dust; above all, when chemists sell arsenic for a toothpowder and label it mercury?[11]

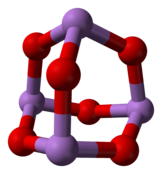

Arsenic trioxide—also known as white arsenic—is an industrially produced inorganic compound with the formula As

2O

3. It is white or colourless and is commonly found in either powdered or crystal form—the latter resembling sugar or sand. It is used as a wood preservative and a pesticide.[14][15]

William Hardaker, known to locals as "Humbug Billy", sold sweets from a stall in the Greenmarket in central Bradford, an industrial town in West Yorkshire, England. Hardaker purchased his confectionary from Joseph Neal, who made the sweets on Stone Street a few hundred yards to the north.[16][17] The in question were peppermint lozenges, made by mixing peppermint oil into a base of sugar, water and gum, which was made into a paste, then dried on boards before being cut into lozenge shapes. As the sugar was relatively expensive, Neal would substitute some of the sugar with powdered gypsum; he later justified his actions by saying "where I use a pound of it, there are people who will use a ton of it".[18]

Outbreak[edit]

In the week before the regular Saturday market, Neal was due to make a batch of lozenges for Hardaker but had run out of "daft". Neal asked his lodger, James Archer, to visit a druggist in the town of Shipley five miles (eight kilometres) away to purchase the gypsum.[19][5] The druggist, Charles Hodgson, was ill in bed; his assistant, William Goddard, was on duty and had been told the daft was in a barrel in the attic.[20] Goddard had only been working for Hodgson for a few weeks, hoping for an apprenticeship.[21] When Archer asked for the daft, Goddard went to the attic and took twelve pounds (five kilograms) of powder from a cask. What he did not realise was that there were two identical barrels and he had taken powder from a barrel of arsenic trioxide; the barrel was only labelled as arsenic on the base.[22]

Investigation and charges[edit]

Legacy[edit]

Food Adulteration Act 1860

Pharmacy Act 1868: "After the society opposed two Poison Bills in 1857 and 1859 that did not meet its criteria, a rival United Society of Chemists and Druggists was established in 1860 by pharmacists disgruntled with the lack of progress, and in 1863 the newly established General Medical Council unsuccessfully attempted to assert control over drug distribution."[23]

Food adulteration acts did not work: 1900 English beer poisoning

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Otter 2020, p. 103; Whorton 2010, p. 141.

- ^ Otter 2020, p. 103; Whorton 2010, pp. 142–143; Wilson 2008, p. 164; Monier-Williams 1951, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Monier-Williams 1951, p. 363.

- ^ Whorton 2010, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e Jones 2000.

- ^ Emsley 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Clark 2023.

- ^ Bartrip 1994, p. 895.

- ^ Foxcroft 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Holloway 1995, p. 94.

- ^ "Arsenic for the Million". The Lancet, p. 592.

- ^ Cunningham 2016, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Sheeran 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 177.

- ^ Tiekink 2010, p. 295.

- ^ Cunningham 2016, pp. 7, 46.

- ^ Davis 2009, 487.

- ^ Sheeran 1992, p. 13.

- ^ Cunningham 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Sheeran 1992, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Holloway 1991, p. 227.

- ^ Whorton 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Berridge 1999, pp. 113–114.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- The Annual Register, or, a View of the History and Politics of the Year, 1858. London: J. G. & F. Rivington. 1858. OCLC 1029099095.

- Berridge, Virginia (1999). Opium and the People: Opiate Use and Drug Control Policy in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century England. London: Free Association Books. ISBN 978-1-8534-3413-6.

- Cooper, Andre R. (1996). Cooper's Toxic Exposures Desk Reference. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-56670-220-1.

- Davis, Mark (2009). Bradford Through Time (Kindle ed.). Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-60330-8.

- Emsley, John (2005). The Elements of Murder: A History of Poison. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1928-0599-7.

- Foxcroft, Louise (2007). The Making of Addiction: The 'Use and Abuse' of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5633-3.

- Holloway, S. W. F. (1991). Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1841-1991: A Political and Social History. London: The Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-8536-9244-7.

- Holloway, S. W. F. (1995). "The Regulation of the Supply of Drugs in Britain Before 1868". In Porter, Roy; Teich, Mikuláš (eds.). Drugs and Narcotics in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–96. ISBN 978-0-5214-3163-7.

- Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a Large Planet: Industrial Britain, Food Systems, and World Ecology. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-2267-0596-5.

- Sheeran, George (1992). The Bradford Poisoning of 1858. Halifax: Ryburn. ISBN 978-1-8533-1033-1.

- Tiekink, Edward R. T. (2010). "Anticancer Activity of Molecular Compounds of Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth". In Sun, Hongzhe (ed.). Biological Chemistry of Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 293–310. ISBN 978-0-470-97622-7.

- Whorton, James C. (2010). The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work and Play. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1995-7470-4.

- Wilson, Bee (2008). Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6911-3820-6.

Journals and magazines[edit]

- "Arsenic for the Million". The Lancet. 76 (1946): 592. December 1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)57363-3.

- Bartrip, P. W. J. (1994). "How Green Was My Valance?: Environmental Arsenic Poisoning and the Victorian Domestic Ideal". The English Historical Review. 109 (433): 891–913. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 574537.

- Cunningham, Harry (May 2016). "The Bradford Sweets Poisoning". History Today. 66 (5): 46–47.

- Jones, Ian F. (December 2000). "Arsenic and the Bradford Poisonings of 1858". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 265 (7128): 938–939. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020.

- Monier-Williams, G. W. (December 1951). "Historical Aspects of the Pure Food Laws". British Journal of Nutrition. 5 (3): 363–367. doi:10.1079/BJN19510049.

News[edit]

Websites[edit]

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 22 February 2023.