User:SISU GLADIATORI/sandbox

A gladiator (Latin: gladiator, "swordsman", from gladius, "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

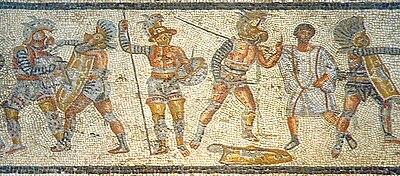

Irrespective of their origin, gladiators offered spectators an example of Rome's martial ethics and, in fighting or dying well, they could inspire admiration and popular acclaim. They were celebrated in high and low art, and their value as entertainers was commemorated in precious and commonplace objects throughout the Roman world.

The origin of gladiatorial combat is open to debate. There is evidence of it in funeral rites during the Punic Wars of the 3rd century BC, and thereafter it rapidly became an essential feature of politics and social life in the Roman world. Its popularity led to its use in ever more lavish and costly games.

The gladiator games lasted for nearly a thousand years, reaching their peak between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. The games finally declined during the early 5th century after the adoption of Christianity as state church of the Roman Empire in 380, although beast hunts (venationes) continued into the 6th century.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Early literary sources seldom agree on the origins of gladiators and the gladiator games.[1] In the late 1st century BC, Nicolaus of Damascus believed they were Etruscan.[2] A generation later, Livy wrote that they were first held in 310 BC by the Campanians in celebration of their victory over the Samnites.[3] Long after the games had ceased, the 7th century AD writer Isidore of Seville derived Latin lanista (manager of gladiators) from the Etruscan word for "executioner", and the title of "Charon" (an official who accompanied the dead from the Roman gladiatorial arena) from Charun, psychopomp of the Etruscan underworld.[4] This was accepted and repeated in most early modern, standard histories of the games.[5]

For some modern scholars, reappraisal of pictorial evidence supports a Campanian origin, or at least a borrowing, for the games and gladiators.[6] Campania hosted the earliest known gladiator schools (ludi).[7] Tomb frescoes from the Campanian city of Paestum (4th century BC) show paired fighters, with helmets, spears and shields, in a propitiatory funeral blood-rite that anticipates early Roman gladiator games.[8] Compared to these images, supporting evidence from Etruscan tomb-paintings is tentative and late. The Paestum frescoes may represent the continuation of a much older tradition, acquired or inherited from Greek colonists of the 8th century BC.[9]

Livy places the first Roman gladiator games (264 BC) in the early stage of Rome's First Punic War, against Carthage, when Decimus Junius Brutus Scaeva had three gladiator pairs fight to the death in Rome's "cattle market" forum (Forum Boarium) to honor his dead father, Brutus Pera. This is described as a "munus" (plural: munera), a commemorative duty owed the manes (spirit, or shade) of a dead ancestor by his descendants.[10][11] The development of the munus and its gladiator types was most strongly influenced by Samnium's support for Hannibal and the subsequent punitive expeditions against the Samnites by Rome and its Campanian allies; the earliest and most frequently mentioned type was the Samnite.[12]

The war in Samnium, immediately afterwards, was attended with equal danger and an equally glorious conclusion. The enemy, besides their other warlike preparation, had made their battle-line to glitter with new and splendid arms. There were two corps: the shields of the one were inlaid with gold, of the other with silver ... The Romans had already heard of these splendid accoutrements, but their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, not adorned with gold and silver but putting his trust in iron and in courage ... The Dictator, as decreed by the senate, celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured armour. So the Romans made use of the splendid armour of their enemies to do honour to their gods; while the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped after this fashion the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts, and bestowed on them the name Samnites.[13]

Livy's account skirts the funereal, sacrificial function of early Roman gladiator combats and reflects the later theatrical ethos of the Roman gladiator show: splendidly, exotically armed and armoured barbarians, treacherous and degenerate, are dominated by Roman iron and native courage.[14] His plain Romans virtuously dedicate the magnificent spoils of war to the gods. Their Campanian allies stage a dinner entertainment using gladiators who may not be Samnites, but play the Samnite role. Other groups and tribes would join the cast list as Roman territories expanded. Most gladiators were armed and armoured in the manner of the enemies of Rome.[15] The munus became a morally instructive form of historic enactment in which the only honourable option for the gladiator was to fight well, or else die well.[16]

Development[edit]

In 216 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, late consul and augur, was honoured by his sons with three days of gladiatora munera in the Forum Romanum, using twenty-two pairs of gladiators.[17] Ten years later, Scipio Africanus gave a commemorative munus in Iberia for his father and uncle, casualties in the Punic Wars. High status non-Romans, and possibly Romans too, volunteered as his gladiators.[18] The context of the Punic Wars and Rome's near-disastrous defeat at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) link these early games to munificence, the celebration of military victory and the religious expiation of military disaster; these munera appear to serve a morale-raising agenda in an era of military threat and expansion.[19] The next recorded munus, held for the funeral of Publius Licinius in 183 BC, was more extravagant. It involved three days of funeral games, 120 gladiators, and public distribution of meat (visceratio data)[20] – a practice that reflected the gladiatorial fights at Campanian banquets described by Livy and later deplored by Silius Italicus.[21]

The enthusiastic adoption of gladiatoria munera by Rome's Iberian allies shows how easily, and how early, the culture of the gladiator munus permeated places far from Rome itself. By 174 BC, "small" Roman munera (private or public), provided by an editor of relatively low importance, may have been so commonplace and unremarkable they were not considered worth recording:[22]

Many gladiatorial games were given in that year, some unimportant, one noteworthy beyond the rest — that of Titus Flamininus which he gave to commemorate the death of his father, which lasted four days, and was accompanied by a public distribution of meats, a banquet, and scenic performances. The climax of the show which was big for the time was that in three days seventy four gladiators fought.[23]

In 105 BC, the ruling consuls offered Rome its first taste of state-sponsored "barbarian combat" demonstrated by gladiators from Capua, as part of a training program for the military. It proved immensely popular.[24] Thereafter, the gladiator contests formerly restricted to private munera were often included in the state games (ludi)[25] that accompanied the major religious festivals. Where traditional ludi had been dedicated to a deity, such as Jupiter, the munera could be dedicated to an aristocratic sponsor's divine or heroic ancestor.[26]

Peak[edit]

Gladiatorial games offered their sponsors extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for self-promotion, and gave their clients and potential voters exciting entertainment at little or no cost to themselves.[27] Gladiators became big business for trainers and owners, for politicians on the make and those who had reached the top and wished to stay there. A politically ambitious privatus (private citizen) might postpone his deceased father's munus to the election season, when a generous show might drum up votes; those in power and those seeking it needed the support of the plebeians and their tribunes, whose votes might be won with the mere promise of an exceptionally good show.[28] Sulla, during his term as praetor, showed his usual acumen in breaking his own sumptuary laws to give the most lavish munus yet seen in Rome, for the funeral of his wife, Metella.[29]

- ^ Welch 2007, p. 17; Kyle 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Welch 2007, pp. 16–17. Nicolaus cites Posidonius's support for a Celtic origin and Hermippus' for a Mantinean (therefore Greek) origin.

- ^ Futrell 2006, pp. 4–7. Futrell is citing Livy, 9.40.17.

- ^ Futrell 2006, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Welch 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Welch 2007, p. 18; Futrell 2006, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Futrell 2006, p. 4; Potter & Mattingly 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Potter & Mattingly 1999, p. 226. Paestum was colonized by Rome in 273 BC.

- ^ Welch 2007, pp. 15, 18.

- ^ Welch 2007, pp. 18–19. Livy's account (summary 16) places beast-hunts and gladiatorial munera within this single munus.

- ^ A single, later source describes the gladiator type involved as Thracian. See Welch 2007, p. 19. Welch is citing Ausanius: Seneca simply says they were "war captives".

- ^ Wiedemann 1992, p. 33; Kyle 1998, p. 2; Kyle 2007, p. 273. Evidence of "Samnite" as an insult in earlier writings fades as Samnium is absorbed into the republic.

- ^ Livy 9.40. Quoted in Futrell 2006, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Kyle 1998, p. 67 (Note #84). Livy's published works are often embellished with illustrative rhetorical detail.

- ^ The velutes and later, the provocatores were exceptions, but as "historicised" rather than contemporary Roman types.

- ^ Kyle 1998, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Welch 2007, p. 21. Welch is citing Livy, 23.30.15. The Aemilii Lepidii were one of the most important families in Rome at the time, and probably owned a gladiator school (ludus).

- ^ Futrell 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Futrell 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Livy, 39.46.2.

- ^ Silius Italicus quoted in Futrell 2006, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Welch 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Livy, Annal for the Year 174 BC (cited in Welch 2007, p. 21).

- ^ Wiedemann 1992, pp. 6–7. Wiedemann is citing Valerius Maximus, 2.3.2.

- ^ The games were always referred to in the plural, as ludi. Gladiator schools were also known as ludi when plural; a single school was ludus

- ^ Lintott 2004, p. 183.

- ^ Mouritsen 2001, p. 97; Coleman 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Kyle 2007, p. 287; Mouritsen 2001, pp. 32, 109–111. Approximately 12% of Rome's adult male population could actually vote; but these were the wealthiest and most influential among ordinary citizens, well worth cultivation by any politician.

- ^ Kyle 2007, p. 285.