User:RobertKennesy/Sandbox

Night Music is a musical style of the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók which he used mostly in slow movements of multi-movement ensemble or orchestra compositions in his mature period. It is characterized by "eerie dissonances providing a backdrop to sounds of nature and lonely melodies.[1]"

Gallery[edit]

-

The memorial plaque in recognition of its former Surgeon-in-Chief and Director, Dr. Albert Kenessey, at the main entrance of the hospital in Balassagyarmat, Hungary, which is named after him.

-

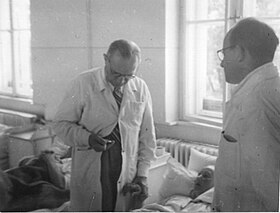

Kenessey (left) at work in the hospital in Balassagyarmat

-

Kenessey (center, back) at work as surgeon

- Mood:

- night - nature - insects (buzzing;diary of a fly)

- spaciousness

- eerie

- lonely melodies

- Material:

- parlando improvisational passage (pc2)

- chorale

- melody: espressivo;viola or cello recitative (chromatic/pentatonic)

- klangflach

- gefundene objecte in the external world (Kundera): peasant flute melody in szabadban; animal noises (irregular time intervals within the meter)

- Technique:

- wide pitch ranges

- Overlap and insertions of widely different materials (dense cluster chords combined with spacious klangflach)

- Sound portrayal as opposed to traditional melody and harmony - Geräusch

- Music theoretical:

- dissonance

- dachenka

- runs (glisses)

- motivs

- repeated note

- trills tremolos rolls

- cluster chords

Characteristics of Night music[edit]

As with many musical styles, it is not possible to make a satisfying let alone undisputable definition of Night music. Bartók did not say or explain much about this style. Most of the works in Night music style do not carry a title. From an audience point of view "'Night Music' consists of those works or passages which convey to the listener the sounds of nature at night[2]". This is quite subjective and self-referential. Mostly, subjective and far-fetched descriptions are available: "quiet, blurred cluster-chords and imitations of the twittering of birds and croaking of nocturnal creatures",[3] "In an atmosphere of hushed expectancy, a tapestry is woven of the tiny sounds of nocturnal animals and insects.[4]" More concrete is "Eerie dissonances providing a backdrop to sounds of nature and lonely melodies[1]".

Instead of an attempt at defining, a list of characteristics of 'Night music' is more useful.

- Sound portrayal as opposed to traditional melody and harmony. An example of Bartók's focus on sound quality are the minute directions on how the percussion instruments in the Sonata for two pianos and percussion have to be played. This sound portrayal includes:

- The direct imitations of natural sounds, mostly of nocturnal animals. Also the term nature music is sometimes used. Milan Kundera, in commenting on Bartók's expansion of art music with natural sounds, writes "sounds of nature inspire Bartók to melodic motives of a rare strangeness".[5]

- Evocations of the mood of night and spaciousness.

- Melodies are portrayed in the music, rather than being a direct means of (self-)expression. For instance, a pastoral flute and its melody are portrayed in The Night’s Music from Out of Doors. The effect on the listener is not primarily the esthetic effect of the melody. The melody's effect is rather indirect: the evocation of being out of doors at night in the plain and hearing the shepherd play his melody.[6] In the words of Milan Kundera, not only the natural sounds at night, but also the lonely songs and melodies, far from being a Lied or other self-expression of the composer, find their origin in the external world.[7] In the words of Schneider "Bartók seems to be suggesting musically the old Romantic organicist idea that peasant [and shepherds'] music is a natural phenomenon, a view he expressed in writing on several occasions". He also points out that "the G#’s [in bar 37 which start as the mere sound of repeated notes and turn into the shepherd's melody] gradually emerge from the myriad of other natural sounds".[8]

- On a more technical musical level, a piece or movement of night music style may show any of the following characteristics.

- An ostinato sound on every beat in the slow prevailing tempo, often this sound is dissonant, and/or a cluster chord. Because of the slow and repetitive nature, these sounds come to fulfil an accompanying or background role.

- Curt motives at irregular time intervals within the meter. These motives may be the imitations of the natural sounds or more abstract, often primitive, motives. An example is A,A,A,C,A,A in the second movement of the Sonata for two pianos and percussion. This motive is scored as a quintuplet of sixteenths in 4/4 time on the third beat, plus a sixteenth note on the fourth beat: the last A. As the implied or latent rhythm is 3+2+1, it sounds as an accelerando which evaporates suddenly.

- Wide pitch ranges in glissandi, jumps and doublings over many octaves. This contrasts heavily with cluster chords of adjacent notes and trills and may well add to the evocation of spaciousness or loneliness.[9]

- Overlap and insertions of widely different materials, e.g. a bird call in a melodic line. Different materials sound irrespective of one another leading to novel sound effects, and, more subjectively, multiple layers and perhaps the feeling of spaciousness.

Compositions in Night music style[edit]

Night music developed stepwise and has unclear boundaries to other musical types. Yet, a list of pieces of Night music can be established including its precursors. In some cases one could argue that only specific sections within a piece or movement are Night music. Danchenka's list (1987, copied, including an error in Schneider (2006)) of some works contains at many entries which exact bars are Night music. For instance, only the middle section of the Piano Concerto No. 3 is included. However, Gillies (1993) points out how the main melodic material of the opening and closing sections are related to the bird calls of the middle section. As the bird calls could not be modified to match other melodic material, the opening and closing section have to have been directly derived from the bird calls.

- Second Suite for small orchestra Op. 4, Sz. 34, BB 40, mvt. 3, Andante 1905

- Fourteen Bagatelles Op. 6, nr.12. 1908

- Fragments of sections and moods in the opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle 1911(-1917)

- Five songs op. 15 nr. 5, Here down in the valley (Hungarian: Itt lenn a völgyben) 6 February, 1916

- The Miraculous Mandarin Op. 19. 1918-1924. Rehearsal 101 in which, in the dark, "The body of the Mandarin begins to glow with a greenish blue light".

- Eight Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs op.20, nr.3. 1920

- The Night’s Music of the five piano pieces Out of Doors, Lento – (un poco) pìu Andante 1926 listen

- Piano Concerto No. 1, mvt. 2, Andante 1926

- String Quartet No. 3, mvt. 3, Moderato 1927

- String Quartet No. 4, mvt. 3, Non troppo lento 1928

- Piano Concerto No. 2, mvt. 2, Adagio – Più adagio – Presto - Tempo I, 1931

- String Quartet No. 5, mvt. 2 Adagio molto and 4 Andante 1934

- Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, mvt. 3, Adagio 1936

- Sonata for two pianos and percussion, mvt. 2, Lento, ma non troppo Video of Marta Argerich and Nelson Freire 1937

- Mikrokosmos, Nr 107 Melody in the Mist- tranquillo Listen to György Sándor playing most of it., and Nr. 144, Minor seconds, Major Sevenths - LentoAnd here playing Minor Seconds, Major Sevenths published 1940.

- Concerto for Orchestra (Bartók), Introduction of mvt. 1 and mvt. 3, ‘‘Elegia’’ Video of mvt. 1Video of mvt. 3 1943

- Piano Concerto No. 3, mvt. 2, Adagio religioso Video of Zoltán Kocsis Video of András Schiff 1945

- Sketches for a Viola Concerto, mvt. 2, Adagio religioso 1945

Development of Night music in Bartók's output[edit]

As a modernist composer, Bartók did not compose music as the esthetic expression of human ethics,[10] and as a reserved personality he shunned sentimentality, specifically breaking with Romantic nineteenth century music. The development of Night music was influenced by sound effect compositions by Debussy and Ravel as well as pre-Bachian composers like Couperin. Schneider shows the influence of the Hungarian style of musical depictions of nature, night and the vast open space by the Hungarian composers Erkel, Mosonyi, Szendy, Weiner, and Dohnányi. Close family of Bartók agree that inspiration for Night music came from sounds in the summer nights at Szőllőspuszta where Bartók visited his sister from 1921 onwards. This estate lies in Békés county in the Great Hungarian Plain, Nagy Alföld.

The Song op. 15 nr. 5 Here down in the valley is a song in the Lied tradition. Consequently, nature is not objectively portrayed as it is in Night music but nature mirrors the emotions of the subject. Nonetheless, it contains a night music characteristic: arpeggiated clusters of three adjacent notes in the medium and lower registers on the piano, played forte. The text is not particularly strong, but greater forces than artistic value (let alone reason) formed the inspiration: Bartók was madly in love with the poetess.

INTERMEZZO [11] The genesis of Here down in the Valley

Starting in the summer of 1915, Bartók (by that time 34 years old) undertook collection trips of Slovakian folk music in the country while staying in the mansion of Gombossy, the chief forester of the comitatus Zólyom, near the town of Kisgaram (now Hronec in central Slovakia). The forester had a fourteen-year-old daughter, Klára, whom Denijs Dille later described as of lively intelligence and openness of character and at fourteen coquettish, strong-willed and mischievous. She went along on Bartók’s trips and although she played piano, we can assume that her stimulating support soon extended beyond the musical level. She was not only musically but also literary inclined and showed the composer a number of her poems, all in a late Romantic style: pathetic, egocentric, sentimental, hysteric. In short, entirely alien to Bartók's modernism. Nonetheless, Bartók was quite impressed. In a single day, on 6 February 1916, he wrote the music to one of them, ‘Here down in the valley’. Given the text, the traditional Lied was a better idiom than a fully modernist song. Bartók is said to have been ready to leave his wife and his five-year-old son to marry Klára. She refused, even her friend Wanda Gleiman, author of one song in op. 15, could not convince her. By October 1916 he ended his correspondence with Klára. Much later Bartók admitted the texts of his songs op. 15 are ‘not particularly good’; Klára's spell had worn off. He wanted to publish them but only if his publisher would not mention the authors of the texts. As his publisher was afraid of copyright breach, it was left unpublished until 1958. In the first editions Bartók himself and the accomplished hungarian poet Ady Endre were suggested as the hidden text writer. Denijs Dille discovered the true authorship from interviews with both girls in the late 1970's, shortly before their passing.

The first composition in fully developed Night music style, "the locus classicus of a uniquely Bartókian contribution to the language of musical modernism",[12] is the fourth piece of the Out of Doors set for solo piano, the instrument he knew best (June 1926). This piece is called The Night’s Music and bestowed its name on the entire style. Despite its immediate success,[13] Bartók realised the piano is ill suited for compositions of overlapping, widely differing musical textures. Therefore, he employed ensembles and orchestras for his further compositions in mature Night music style: slow movements of, among others, concerti and string quartets. Bartók wrote only two more solo piano pieces of night music type: Mikrokosmos nr. 107 Melody in the Mist and nr. 144, Minor seconds, major sevenths.

Melody in the Mist is technically really quite easy [14]) but shows a number of characteristics of Night music. There is an overlapping alteration of "Mist": a block chord of G-A-C-D around middle C, going up and down in semitones; and an unaccompanied "lonely" "Melody" from the "the external world": a mostly anhemitonic pentatonic (Hungarian Old style(!)) melody with pitch inventory G-A-C-D-F (F once changed to a conventional leading tone F#), unaccompanied and sometimes doubled at a distance of one or two octaves. At the end the block chord of G-A-C-D and that very chord but a semitone up (G#-A#-C#-D#) sound simultaneously.

One of Bartók's most performed pieces is his Concerto for Orchestra. The opening bars present a theme of rising fourths in cellos and basses, answered by tremolando strings and fluttering flutes in Bartók's characteristic "Night music" style. Trumpets, pianissimo, chant a pungent, short-phrased chorale [...] Bartók described the keystone third movement, "Elegia," as a "lugubrious death-song," in which unsettled "night music" effects alternate with intense, prayerful supplications (again related to the chorale-like material that pervades the first half of the work).

Bartók's last composition which contains Night music style is the slow movement of his third piano concerto, written in August and September 1945. He wrote it when mortally ill, he died September 26.

The movement opens and closes in an almost Romantic style, the middle section contains sounds of nature. Kundera wrote: The hypersensitive theme, unspeakably melancholic, is contrasted with the other, hyperobjective theme [...]: as if a soul in tears can only find solace in the non-sensitivity of nature. The natural sounds are still mysterious and full of anticipation, but not at all eerie. They are rather peaceful, perhaps light, as if in his last night music, a bright new morning is ready to break.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Schneider, p.84

- ^ Daschenka, p.16

- ^ Brown pp. 258-59

- ^ Bela Bartok

- ^ Kundera, p. 71

- ^ One could make a comparion to Beethoven portrayal of pastoral scenes in his Pastoral Symphony.

- ^ Kundera

- ^ Schneider, p. 116

- ^ Schneider p. 82

- ^ quoted from Ernest Ansermet in Kundera, p. 67

- ^ Denijs Dille, Béla Bart:Regard sur le Passe, ed. Yves Lenoir ( Louvain-la Neuve: Institut Supérieur d'Archeologie et d'Histoire de L'Art,College trasme, 1990), 257-77. In a long article devoted to clarification of long-standing questions that regarded the composition of Bartók's op. 15 songs, Dille publishes his findings traced from 1978 to 1989. He presents and judges conflicting evidence gathered directly from Klára Gombossy and her childhood friend Wanda Gleiman, as well as from correspondence and music manuscripts. The article refutes much that had been published earlier regarding the op. 15 songs, including Dille's own remarks in the Universal Edition(U.E. 13150) of 1961 and in program notes (written in 1972) for the Hungaroton recording SLPX 11603. See Dille, Béla Bartók, 269-70, 276.

- ^ Schneider p.81

- ^ The piece was censored in communist Hungary as "a monstrous document of imperialism" in the words of the censor Sándor Asztalos, quoted in Fosler-Lussier , p 61)

- ^ Level 5 of 15, within "beginner" range in Yeomans (1988)

Sources[edit]

- Brown, M.J.E., (1980) The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, (ed. Sadie),London, MacMillan, 1980 (1995), Vol. 13, ISBN 0333231112 ISBN 978-0333231111.

- Danchenka, Gary. "Diatonic Pitch-Class Sets in Bartok's Night Music" Indiana Theory Review 8, no. 1 (Spring, 1987): 15-55.

- Fosler-Lussier, D., (2007) Music Divided: Bartók’s Legacy in Cold War Culture. (California Studies in 20th-Century Music) ISBN 978-0520249653

- Gillies, M. editor (1993) The Bartók Companion. ISBN 0-931340-74-8

- Harley, M.A., (1995) "Natura naturans, natura naturata" and Bartok's Nature Music Idiom, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, T. 36, Fasc. 3/4, Proceedings of the International Bartok Colloquium, Szombathely, July 3–5, 1995, Part I (1995), pp. 329–349 doi:10.2307/902218

- Kundera, Milan (1993), Les Testaments trahis, Editions Flammarion (24 septembre 1993), ISBN 2070736059, ISBN 978-2070736058

- Schneider, D., (2006) Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality (California Studies in 20th-Century Music) ISBN 978-0520245037

- Yeomans, D. (1988) Bartók for piano. ISBN 0-253-21383-5 (Subtitle: A survey of his solo literature.)

- Schneider, David E. (2006) in

Gillies 2006, 317-318 and see also Schneider 1995, 183-187.

- Gillies, Malcolm (2006). "Bartók's "Fallow Years": A Reappraisal". Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 47, Numbers 3-4 / September 2006. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISSN 0039-3266 (Print) 1588-2888 (Online) DOI 10.1556/SMus.47.2006.3-4.7

- Schneider, David E. (1995). "Bartók and Stravinsky: Respect, Competition, Influence and the Hungarian Reaction to Modernism in the 1920s". In Bartók and his world, edited by Peter Laki, 172-202. Princeton: Princeton University Press ISBN 978-0691006338

Further reading[edit]

- Bayley, A., editor (Cambridge University Press March 26, 2001) The Cambridge companion to Bartók. ISBN 978-0521669580

- Bartók, Béla (1976). Béla Bartók Essays. ed. Benjamin Suchoff. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0571101208. OCLC 60900461.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origdate=(help) - Nissman, B., (2002) Bartók and the Piano a Performer's View. ISBN 0-8108-4301-3

- Stevens, H. (1953) The Life and Music of Béla Bartók ISBN 978-0198163497

- Somfai, L. (1996), Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources (Ernest Bloch Lectures in Music) ISBN 978-0520084858

from http://www.es.hu/pd/display.asp?channel=FEUILLETON0628: Péter László: Bartók és Ady

Bartók 1916-ban írt két - egyenként öt-öt dalból álló - sorozatot. Ezek műveinek jegyzékében az Opusz 15. és 16. jelzést kapták.6 Mind a kettõ bizonyos rejtélyt kínált az irodalom és a zene történetének kutatói számára. Mind a kettõnek dalai ugyanis nem hatnak olyan művészi erõvel, mint ahogyan ezt a hozzáértõk Bartóktól várták és várnák. László Ferenc nálam keményebben fogalmazta meg véleményét: "Bartók mélyen alkotói rangja alatti versekre pazarolta zeneszerzõi képességeit, amelyek nemcsak tartalmukban, hanem költõi kivitelezésükben is méltatlanok voltak hozzá."7

Az Opusz 15. öt verse közül négynek költõje egy tizenöt éves diáklány, Gombossy Klára (1901-1980), akinek kétségtelen ifjúi tehetsége mellett bizonyára szépsége tette elfogulttá az akkor lelki és alkotói válságban vergõdõ Bartókot.8

Bartók 1915 nyarán szlovák népzenét gyűjtött a Besztercebánya körüli falukban. Kisgaramon (ma Hronec Szlovákiában) Gombossy József erdõmérnök szállásolta el hivatalának vendégszobájában. Bartók ugyanis Nagyszõllõsön Gombossynéval együtt járt elemi iskolába. Bartókot gyűjtõútjaira elkísérte a korához képest érett és fejlett, sudár termetű lánya. A szlovák dalszövegek lejegyzésében és fordításában segített neki. Bartókot megigézte a fiatal lány. Fölfigyelt költõi szárnypróbálgatásaira, és néhány versét magával vitte. Hármat (Tavasz, Nyár, Õsz) 1916 februárjában meg is zenésített. A negyediket (Tél) átírta, és utóbb augusztusban szintén megkomponálta. Szövegüket Kodály Zoltánné, Emma asszony fordította németre. Az Opusz 15. ötödik dalát (A vágyak éjjele) Gombossy Klára zongoratanárnõjének, Gleimanné Hickel Mária Jozefának és dr. Gleiman Kálmán zólyombrézói orvosnak a lánya, Gleiman Wanda (1897-1963), a késõbbi (1923 utáni) báró Radvánszky Antalné írta.9 Õ fordította magyarra a négyszólamú férfikarra a capella írt Tót népdalok (1917) szlovák szövegeit.

Bartók és Gombossy Klára idillje 1916 októberében szakadt meg. Ez a kapcsolat - Somfai László szerint - jelentõssé azért vált, mert segített föloldani Bartókban a lelki válságából fakadt kompozíciós görcsöt: 1916 télutolján "robbanásszerűen", "nyersen felszakadó lírai dalokkal elindított egy igen tevékeny és új stílusú alkotásokban gazdag esztendõt". Február elején Bartók megzenésítette Gombossy Klára három versét; februárban írta a Szvit zongorára (Op. 14.) partitúráját; április végén a Nyitra megyei Tavarnokba visszavonulva három hónap alatt befejezte A fából faragott királyfit. E táncjáték mondandója is hozzájárult, hogy mintegy kiírja magából kínzó gondjait, és így túljutott a válságon.

Február és április közt készült az Öt dal, énekhangra zongorakísérettel, Ady Endre verseire. Bartók könyvei közt, láttuk, ott volt a Vér és arany, de benne korábban nem jelölte meg azokat a verseket, amelyeket 1916-ban megzenésített! NOTES at HUNGARIAN; 5 Denijs Dille (1904–2005): Bartók és Ady. Studia Musicologia Academiæ Scientiarum Hungariæ. 1981. 128-129. 125-133. = D. D.: Béla Bartók, 293-302. Az Adytól idézettek forrását sajnos, nem jelölte meg. 6 Somfai László: [Lemezismertetõ.] = Bartók Béla összkiadás. 1968. Vokális művek. 4. sorozat 1. lemezhez. 7 László Ferenc: Bartók és dalszövegei. Magyar Zene, 2004. 415-430. 8 Szegõ Júlia: Három Bartók-dal megtalált ihletõje. Korunk, 1963. 1631-1635. - Denijs Dille: Béla Bartóks opus 15. = Zur Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts. Szerk. C. Flores, H. J. Marx, P. Petersen. Hamburg, 1980. 201-213. - Denijs Dille: L'Opus 15 de Béla Bartók. = D. D. : Béla Bartók. Louven, 1990. 257-278. 9 Denijs Dille: Bartók et Ady, i. m. 125-133. = D. D.: Béla Bartók, 293-302.

666666666666666666666666666666666666666 66666666666666666666666666666 66666666666666666666666666666666

In 1904, while staying in the Slovakian countryside in order to practice and compose, Bartók overheard Lidi Dósa, a Székely Hungarian woman from Transylvania, sing the song Piros alma ("Red Apple"). van http://homepage.eircom.net/~braddellr/disso/index.htm :

In December 1904, while on holiday in the northern resort town of Gerlicepuszta (now Ratkó in Slovakia), Bartók heard the singing of Lidi Dósa, an eighteen-year-old nursemaid originally from the Székely province of Transylvania. She gave a rendition of the following folksong: [1]

Ex. 2.1: Hungarian Folk song.

This song transforms the harmonic minor scale into an alternation of the Dorian and Aeolian folk modes (Ex. 2.2). As the pitches A and E are not placed on strongly accented beats, it can be shown that the melody has a pentatonic (G-Bb-C-D-F) substructure,

Ex. 2. 2: Hungarian Folk Music Scales

G-Dorian Folk Mode plaatjes opgeslagen op PC thusi G-Aeolian Folk Mode

Pentatonic Scale

Benjamin Suchoff draws our attention to the unusual structure of the melody, which deviates from the common four-line da capo (AABA) form, into a more unorthodox three-line (ABC) design.[2] This modification of form and tonality was a revelation to Bartók.

1904-ben azonban igazi, „tiszta forrásból” csordogáló dallam változtatott zeneszemléletén:

Az ifjú zeneszerző és zongoraművész, a budapesti Zeneakadémia végzettje, a Gömör megyei Gerlicepusztára vonult vissza gyakorolni és komponálni. Egy ugyanott nyaraló budapesti családnak volt egy székely cselédje, Dósa Lidi, aki szívesen énekelgetett a gondjára bízott gyermekeknek. Bartók felfigyelt rá, és hét – vagy annál több – dalát lekottázta. Ezek a legkorábbi Bartók-gyűjtötte népdalok.

Később, megismerkedve Kodály Zoltánnal, tudatosan fordult a népzene kutatása felé. 1907-ben Székelyföldön járt, ahol – ahogy írta – „népzenei tündérországgal” találkozott.

„Megtaláltam a székely népdaltípusokat, amiről nem hittem, hogy léteznek“ – lelkesedett, az ereszkedő szerkezetű, pentaton hangrendszerű dallamkincs felfedezésekor.

Amint hazaért, Bartók egy zongoraminiatűrben állított örök emléket a Székelyföldnek: ez az „Este a Székelyeknél”.

77777777777777777 777777777777777777 Az én szerelmem nem sápadt[bleek] éji hold,mely elmerengve [musing] néz a vízbe le, Az é szerelmem forró déli napfény, termetõ [scheppende kracht] erõvel, tüzzel tele Az én ajkamom forró csók a rózsa,az é szememben gyujtó tüzek égnek, Az é testemben örök [eternal] ifjan lángol [burn, glow] pogány [heathen; pagan; profane], szerelmes mámora [mámor intoxication] a vérnek.

Szomjasan vágyva várom a szellõt[breeze], A kék égharang [hjemel-koepel] vakít [verblindt] feletem. Rajta árnyat hiába kerestem, A nap megolvasztott minden felhõt Nyitott szájjal szívtam a napsugárt, A lángoló [blazing] ég szinte [lijkt] rámszakadt és a lombos[leafy], sürü [thick] , zöld fák alatt A rohanó nyár egy percre megállt

Csókolni! ajkam most csókra vágyik! Ez most a vágyik éjjele. Ezernyi [duizend] kéj [pleasure] ég [branden] a sötétben, Az ég is megremeg [quiver] bele, Lázas forróság perszeli szájam: Ez most a vágyik éjjele Csókolni! Ajkam most csókra vágyik! Suhog a vágyak veszszeje, Ütése fáj, ütése éget, és szemem könynyel van tele. Ó fájó kinok, édes kinok! Ez most a vágyik éjjele Csókolni! Ajkam most csókra vágyik! Vérem ez éjjel tüzfolyó, Meztelen karom vágyva kitárom, testemrõl lehull a takaró, A gazdag vágyak éjszakáján Csókolni, ölelni volna jó! Vergõdöm gyürött párnáimon Megváltó reggel! Meszsze vagy-e? Ments meg a vágyak tüzveszszejétõl Félek, hogy meghalok bele! Ajkam ez éjjel csókra vágyik, Ez most a vágyik éjjele.

Szines álomban látalak mar, Ismerem arcod én, Szerelmes szivel, égõ szájjal jöttél akkor felém. Szólj, te vagy-e megértõ társam, Kit lelkem keresett? Nem foglak-e elvesziteni, ha megismertelek? Mondd, elfogadod tõlem életem? Minden értéke, fénye most tiéd. Néked õriztem hosszú éveken, Ki után annyi utat bejártam. Hiszek abban, hogy megtaláltalak, Hiszek abban, Hiszek abban, Hiszek benned, én lelki társam.