User:Rjensen/Britain-entry wwI

draft from Sept 3 2018 mostly used

Background[edit]

Copy ex"Allies of WWI" Sept 10 2018[edit]

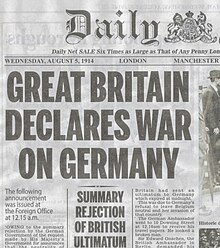

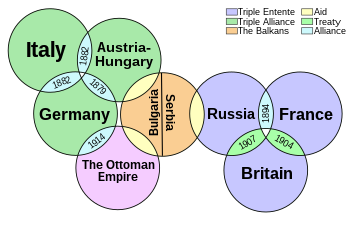

British leaders increasingly had a sense of commitment to defending France against Germany – first if Germany again conquered France, it would become a major threat to British economic, political and cultural interests. Secondly, partisanship was involved. The Liberal Party was identified with internationalism and free trade, and opposition to jingoism and warfare. By contrast the Conservative Party was identified as the party of nationalism and patriotism; Britons expected it "to show capacity in running a war." [1] Liberal voters demanded peace, but they also were outraged when the Germans treated Belgian neutrality as a worthless "scrap of paper" (in the words of the German chancellor ridiculing the Treaty of London (1839)). Germany invaded Belgium en route to a massive attack on France early on the morning of 4 August. The victims called upon Britain for military rescue under the 1839 treaty and in response, Britain declared war on Germany that same evening.[2] As late as August 1, 1914, the great majority of Liberal--both voters and cabinet members--strongly opposed going to war.[3] The German invasion of Belgium was such an outrageous violation of international rights that they voted for war on August 4. Unless the Liberal government acted decisively against the German invasion, its top leaders Including Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, Foreign Minister Edward Grey, navy minister Winston Churchill and others would resign, leading to control of the British government by the much more pro-war Conservative Party. Mistreatment of Belgium itself was not a main cause British entry, but it was a main justification used extensively in wartime propaganda to motivate the British people. [4]

The German high command was aware that entering Belgium would trigger British intervention but decided the risk was acceptable; they expected it to be a short war while their ambassador in London claimed civil war in Ireland would prevent Britain from assisting France.[5]

The declaration of war automatically involved all dominions and colonies and protectorates of the British Empire, many of whom made significant contributions to the Allied war effort, both in the provision of troops and civilian labourers.

Propaganda[edit]

On 4 August, the King declared war on Germany and Austria, following the advice of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith of the Liberal Party. The rest of the Empire automatically followed. The cabinet's basic reasons for declaring war focused on a deep commitment to France and avoidance of splitting the Liberal Party. Top Liberals led by Asquith and Foreign Minister Edward Grey threatened to resign if the cabinet refused to support France. That would deeply split the party and mean loss of control of the government to a coalition or to the Unionist (ie Conservative) opposition. However, the large antiwar element among Liberals, with David Lloyd George as spokesperson, would support the war to honour the 1839 treaty that guaranteed Belgian neutrality. So Belgium rather than France was the public reason given.[6][7][8]

Therefore the public reason given out by the government. and used in posters, was that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the 1839 Treaty of London.

Entry[edit]

King Edward VII's visit to Paris in 1903 stilled anti-British feeling in France, and prepared the way for the Entente Cordiale. Initially however, a colonial agreement against the Kaiser's aggressive foreign policy deepened rather than destroyed the bond between the two countries. The Moroccan Crises of 1905 and 1911 encouraged both countries to embark on a series of secret military negotiations in the case of war with Germany. However, British Foreign Minister Edward Grey realized the risk that small conflicts between Paris and Berlin could escalate out of control. Grey insisted that world peace was in the best interests of Britain and the British Empire.[9] Working with little supervision from the British Prime Minister or Cabinet, Grey deliberately played a mediating role, trying to calm both sides and thereby maintain a peaceful balance of power. He refused to make permanent commitments to France. He approved military staff talks with France in 1905, thereby suggesting, but not promising, that if war broke out Britain would favour France over Germany. In 1911, when there was a second Franco-German clash over Morocco, Grey tried to moderate the French while supporting Germany in its demand for compensation. There was little risk that Britain would have conflicts with anyone leading to war. The Royal Navy remained dominant in world affairs, and remained a high spending priority for the British government. The British Army was small, although plans to send an expeditionary force to France had been developed since the Haldane Reforms. From 1907 through 1914, the French and British armies collaborated on highly detailed plans for mobilizing a British Expeditionary Force of 100,000 combat troops to be very quickly moved to France, and sent to the front in less than two weeks.[10]

France could strengthen its position in the event of war by forming new alliances or by enlisting more young men. It used both methods.[11] Russia was firmly in the same camp, and Britain was almost ready to join. In 1913 the controversial "three year law" extended the term of conscription for French draftees from two to three years. Previously young men were in training at ages 21 and 22 then joined the reserves; now they were in training at ages 20, 21, and 22.[12]

When the war began in 1914, France could only win if Britain joined with France and Russia to stop Germany. There was no binding treaty between Britain and France, and no moral commitment on the British part to go to war on France's behalf. The Liberal government of Britain was pacifistic, and also extremely legalistic, so that German violation of Belgium neutrality – treating it like a scrap of paper – helped mobilize party members to support the war effort. The decisive factors were twofold, Britain felt a sense of obligation to defend France, and the Liberal Government realize that unless it did so, it would collapse either into a coalition, or yield control to the more militaristic Conservative Party. Either option would likely ruin the Liberal Party. When the German army invaded Belgium, not only was neutrality violated, but France was threatened with defeat, so the British government went to war.[13]

The issue of German violation of Belgium neutrality allowed Liberal leaders and the rank-and-file to enthusiastically support the war effort. But defense of Belgium was not the main criteria – the invasion of Belgium meant the imminent invasion and possible defeat of France, and that defeat of France was A major threat to Britain. In any case, once France was defeated, Belgium and the Netherlands would become satellites of Germany. The German High Command was aware entering Belgium would trigger British intervention but decided the risk was acceptable; in common with most of Europe, they expected it to be a short war while their ambassador in London told Berlin that the imminent civil war in Ireland would prevent Britain from assisting France.[14] The delay in declaring war was because the Liberal government preferred to wait until Belgium neutrality had been breached in order to maintain Liberal Party unity.

On 3 August, Germany demanded unimpeded progress through any part of Belgium; when this was refused, the German Army invaded on the morning of 4 August. The Belgians now called for assistance under the 1839 Treaty. Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. The German goal of course was not occupy Belgium – indeed, it promised to make good any damages it did. Its goal was to quickly defeat France and force it surrender. With Germany dominatin Western Europe, Belgium and the Netherlands and Denmark would be German satellites. [15]

The decision for war was a partisan decision made by the Liberal cabinet on August 2; Foreign Minister Grey played the leading role. The Conservative party strongly supported entry into the war, but most Liberals were quite reluctant. Liberals voted for war for two primary reasons: as insisted upon by Foreign Minister Grey and Prime Minister Asquith were twofold: to support France, as Britain had repeatedly but informally promised. And second, to keep the Liberal party together, versus the alternative of turning over the government to a to the warmongering Conservatives, or to a coalition government. There was the fear that the Liberal party would be destroyed by coalition government, as indeed actually happened after 1916. The issue of Belgian was not a top priority for the decision-makers, however it was used as the explanation most acceptable to the basically pacifistic Liberal constituencies. [16]

Historians looking at the July crisis typically conclude that Grey:

- was not a great foreign secretary but an honest, reticent, punctilious English gentleman.... He exhibited a judicious understanding of European affairs, a firm control of his staff, and a suppleness and tact in diplomacy, but he had no boldness, no imagination, no ability to command men and events. [Regarding the war]He pursued a cautious, moderate policy, one that not only fitted his temperament, but also reflected the deep split in the Cabinet, in the Liberal party, and in public opinion. [17]

The king's declaration of war automatically involved all members of the Empire. Canada, Australia abd India made significant contributions to the war effort, both in the provision of troops and civilian labourers.

See also[edit]

- Causes of World War I

- Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I

- French entry into World War I

- German entry into World War I

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Allies of World War I

- Historiography of the British Empire

- British military history

- History of the Royal Navy

- History of the United Kingdom, since 1707

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Trevor Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party 1914-1935 (1966) p 51.

- ^ {cite journal |last1=Nilesh |first1=Preeta |title=Belgian Neutrality and the First world War; Some Insights |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |date=2014 |volume=75 |page=1014 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44158486 |accessdate=25 August 2018}}

- ^ Catriona Pennell (2012). A Kingdom United: Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-959058-2.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee (2005). Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9781134790401.

- ^ Brock, Michael (ed), Brock, Elinor (ed) (2014). Margot Asquith's Great War Diary 1914-1916: The View from Downing Street (Kindle ed.). 852-864: OUP Oxford; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-0198737728.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephen J. Lee (2005). Aspects of British Political History 1914-1995. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9781134790401.

- ^ Bentley B. Gilbert, "Pacifist to interventionist: David Lloyd George in 1911 and 1914. Was Belgium an issue?." Historical Journal 28.4 (1985): 863-885.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977) pp 235-237.

- ^ Thomas G. Otte, "'Almost a law of nature'? Sir Edward Grey, the foreign office, and the balance of power in Europe, 1905-12." Diplomacy and Statecraft 14.2 (2003): 77-118.

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., The Politics of Grand Strategy: France and Britain Prepare for War, 1904-1914." (1969) pp 313-17..

- ^ James D. Morrow, "Arms versus Allies: Trade-offs in the Search for Security." International Organization 47.2 (1993): 207-233. online

- ^ Gerd Krumeich, Armaments and Politics in France on the Eve of the First World War: The Introduction of Three-Year Conscription, 1913-1914 (1985).

- ^ Trevor Wilson, "Britain's ‘Moral Commitment’ to France in August 1914." History 64.212 (1979): 380-390. online

- ^ Brock, Michael (ed), Brock, Elinor (ed) (2014). Margot Asquith's Great War Diary 1914-1916: The View from Downing Street (Kindle ed.). 852-864: OUP Oxford; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-0198737728.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Otte, 488-89=-Clark 551

- ^ Clark 145; Wilson article; Kennedy page 461, Searle pp 522-24; Steiner pages 230-37.

- ^ Clayton Roberts and David F. Roberts, A History of England, Volume 2: 1688 to the present. Vol. 2 (3rd edition, 1991) p. 722.

Further reading[edit]

- Albrecht-Carrié, René. A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958), 736pp; basic survey.

- Anderson, Frank Maloy, and Amos Shartle Hershey, eds. Handbook For The Diplomatic History Of Europe, Asia, and Africa, 1870-1914 (1918) online

- Bartlett, Christopher John. Defence and diplomacy: Britain and the Great Powers, 1815-1914 (Manchester UP, 1993).

- Bartlett, C. J. British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century (1989).

- Brandenburg, Erich. (1927) From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914 (1927) online.

- Bridge F. R. Great Britain and Austria-Hungary 1906-14 (1972).

- Charmley, John. Splendid Isolation?: Britain, the Balance of Power and the Origins of the First World War (1999), highly critical of Grey.

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2013) excerpt

- Sleepwalkers lecture by Clark. online

- Ensor, R. C. K. England, 1870–1914 (1936) online

- Evans, R. J. W.; von Strandmann, Hartmut Pogge, eds. (1988). The Coming of the First World War. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-150059-6. essays by scholars from both sides

- Fay, Sidney B. The Origins of the World War (2 vols in one. 2nd ed. 1930). online, passim

- French, David. British Economic and Strategic Planning 1905-15 (1982).

- Goodlad, Graham D. British Foreign and Imperial Policy 1865–1919 (1999).

- Hamilton, Richard F.. and Holger H. Herwig. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004).

- Herweg, Holger H., and Neil Heyman. Biographical Dictionary of World War I (1982).

- Hinsley, F. H. ed. British Foreigh Policy under Sir Edward Grey (1977) 31 major scholarly essays

- Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (2013). The Origins of the First World War (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317875352.

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860–1914 (1980) in-depth Coverage of diplomacy, military planning, business and cultural relationships, propaganda and public opinion excerpt and text search

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987), pp 194-260. online free to borrow

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of British Naval mastery (1976) pp 205-38.

- Kennedy, Paul M. "Idealists and realists: British views of Germany, 1864–1939." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 25 (1975): 137-156. online

- Lowe, C.J. and Michael L. Dockrill. Mirage of Power: 1902–14 v. 1: British Foreign Policy (1972); Mirage of Power: 1914–22 v. 2: British Foreign Policy (1972); Mirage of Power: The Documents v. 3: British Foreign Policy (1972); vol 1–2 are text, vol 3 = primary sources

- McMeekin, Sean. July 1914: Countdown to War (2014) scholarly account, day-by-day

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 9780812994704.; major scholarly overview

- Matzke, Rebecca Berens. . Deterrence through Strength: British Naval Power and Foreign Policy under Pax Britannica (2011) online

- Mowat, R. B. "Great Britain and Germany in the Early Twentieth Century" English Historical Review (1931) 46#183 pp. 423-441 online

- Murray, Gilbert. The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey, 1906-1915 (1915) 128pp, by a top aide online

- xxx Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, eds. War Planning 1914 (2014) pp 48-79

- Murray, Michelle. "Identity, insecurity, and great power politics: the tragedy of German naval ambition before the First World War." Security Studies 19.4 (2010): 656-688. online

- Neiberg, Michael S. Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (2011), on public opinion

- Neilson, Keith. Britain and the Last Tsar: British Policy and Russia, 1894-1917 (1995) online

- Otte, T. G. July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914 (Cambridge UP, 2014). online review

- Paddock, Troy R. E. A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War (2004) online

- Padfield, Peter. The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914 (2005)

- Papayoanou, Paul A. "Interdependence, institutions, and the balance of power: Britain, Germany, and World War I." International Security 20.4 (1996): 42-76.

- Pribram, A.F. England and the International Policy of the European Great Powers, 1871-1914 (1931) online at Questia

- Rich, Norman. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814-1914 (1991), comprehensive survey

- Ritter, Gerhard. The Sword and the Sceptre, Vol. 2-The European Powers and the Wilhelmenian Empire 1890-1914 (1970) Covers military policy in Germany and also France, Britain, Russia and Austria.

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E. "Triple Alliance and Triple Entente, 1902-1914." American Historical Review 29.3 (1924): 449-473. in JSTOR

- Schmitt, Bernadotte Everly. England and Germany, 1740-1914 (1916). online

- Scott, Jonathan French. Five Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Great War (1927) pp 99-153 online.

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Britain in Europe, 1789–1914, a survey of foreign policy (1937) useful overview online

- Somervell, D.C. The Reign of King George V, (1936) 550pp; covers 1910-35; online free

- Steiner, Zara S. Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977), a major scholarly survey.

- Stowell, Ellery Cory. The Diplomacy of the War of 1914 (1915) 728 pages online free

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (2004). The First World War. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03295-2.

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 (1954) online free

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1996) 816pp.

- Vyvyan, J. M. K. "The Approach of the War of 1914." in C. L. Mowat, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History: Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898-1945 (2nd ed. 1968) online pp 140-70.

- Ward A.W., ed. The Cambridge History Of British Foreign Policy 1783-1919 Vol III 1866-1919 (1923) v3 online

- Williamson Jr., Samuel R. "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7.2 (2011): 205-214.

- Williamson, Samuel R. The politics of grand strategy: Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914 (1990).

- Wilson, Keith M. "The British Cabinet's decision for war, 2 August 1914." Review of International Studies 1.2 (1975): 148-159.

- Wood, Harry. "Sharpening the Mind: The German Menace and Edwardian National Identity." Edwardian Culture (2017). 115-132. public fears of German invasion.

- Woodward, E.L. Great Britain And The German Navy (1935) 535pp; scholarly history online

- Young, John W. "Ambassador George Buchanan and the July Crisis." International History Review 40.1 (2018): 206-224.

Historiography[edit]

- Herwig, Holger H. ed., The Outbreak of World War I: Causes and Responsibilities (1990) excerpts from primary and secondary sources

- Horne, John, ed. A Companion to World War I (2012) 38 topics essays by scholars

- Kramer, Alan. "Recent Historiography of the First World War – Part I", Journal of Modern European History (Feb. 2014) 12#1 pp 5–27; "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part II)", (May 2014) 12#2 pp 155–174.

- Langdon, John W. "Emerging from Fischer's shadow: recent examinations of the crisis of July 1914." History Teacher 20.1 (1986): 63-86, historiography in JSTOR

- Mombauer, Annika. "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I." Central European History 48.4 (2015): 541-564.

- Mulligan, William. "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639–666.

- Winter, Jay. and Antoine Prost eds. The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present (2005)

Primary sources[edit]

- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914 (3 vol 1952).

- Barker. Ernest, et al. eds. Why we are at war; Great Britain's case (3rd ed. 1914), the official British case against Germany. online

- Gooch, G.P. Recent revelations of European diplomacy (1928) pp 3-101. online

- Major 1914 documents from BYU

- Gooch, G.P. and Harold Temperley, eds. British documents on the origins of the war, 1898-1914 (11 vol. ) online

- v. i The end of British isolation -- v.2. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Franco-British Entente -- v.3. The testing of the Entente, 1904-6 -- v.4. The Anglo-Russian rapprochment, 1903-7 -- v.5. The Near East, 1903-9 -- v.6. Anglo-German tension. Armaments and negotiation, 1907-12 -- v.7. The Agadir crisis -- v.8. Arbitration, neutrality and security -- v.9. The Balkan wars, pt.1-2 -- v.10, pt.1. The Near and Middle East on the eve of war. pt.2. The last years of peace -- v.11. The outbreak of war V.3. The testing of the Entente, 1904-6 -- v.4. The Anglo-Russian rapprochment, 1903-7 -- v.5. The Near East, 1903-9 -- v.6. Anglo-German tension. Armaments and negotiation, 1907-12 -- v.7. The Agadir crisis -- v.8. Arbitration, neutrality and security -- v.9. The Balkan wars, pt.1-2 -- v.10, pt.1. The Near and Middle East on the eve of war. pt.2. The last years of peace -- v.11. The outbreak of war.

- Joll, James, ed. Britain and Europe 1793-1940 (1967); 390pp of documents

- Jones, Edgar Rees, ed. Selected speeches on British foreign policy, 1738-1914 (1914). online free

- Lowe, C.J. and Michael L. Dockrill, eds. Mirage of Power: The Documents v. 3: British Foreign Policy (1972); vol 3 = primary sources 1902-1922

- Scott, James Brown, ed., Diplomatic Documents Relating To The Outbreak Of The European War (1916) online

- Wilson, K.M. "The British Cabinet's Decision for War, 2 August 1914" British Journal of International Studies 1#3 (1975), pp. 148-159 online

Category:Historiography of the British Empire Category:History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

External links[edit]

articles[edit]

- Woodward, David R. "Great Britain And President Wilson'S Efforts To End World War I In 1916."

By:Maryland Historian. Jun1970, Vol. 1 Issue 1, p45-58.

Historical Period: 1916. Abstract: A study of the British rejection of an American-sponsored compromise peace in 1916. Concludes that the members of the British War Cabinet were hostile to a compromise because war hysteria in England had committed them to a policy of total victory and because British policymakers distrusted President Wilson's motives in initiating peace feelers. Only Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, favored Wilson's proposal for peace, and Grey's influence in the War Cabinet was waning. Grey, able to assuage American feelings, prevented a possible rupture in Anglo-American relations which could have had disastrous results for the Entente Powers. German refusal to state war aims precluded the possibility of any compromise, but the War Cabinet was pleased by German intransigence. (AN: 45757988)

- The British Response To The House-Grey Memorandum: New Evidence And New Questions.

Academic Journal

By: Cooper, John Milton Jr. Journal of American History. Mar1973, Vol. 59 Issue 4, p958-971. 14p. Historical Period: 1916. Abstract: Presents newly available accounts of the British cabinet's War Committee meeting on 21 March 1916 to discuss the Colonel House's proposal to mediate an end to the war. The evidence contradicts the assertions of David Lloyd George that Sir Edward Grey was responsible for the rejection of the proposal. Grey's memo of the meeting and Maurice Hankey's minutes indicate a general lack of enthusiasm for the idea. Grey appears to have favored its acceptance, but the waffling of Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith and Arthur Balfour, the opposition of Andrew Bonar Law and Lloyd George, and the hopeful military situation in May 1916 ensured its rejection. 18 notes, 3 documents. (AN: 46631698)

Category:History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom Category:Causes of World War I Category:1914 in Europe Category:1914 in international relations Crisis Category:Military alliances involving the United Kingdom