User:RedSquirrel/sandbox5

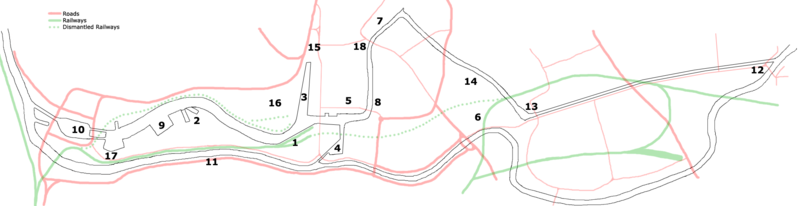

The Centre is a public open space, transport interchange and cultural destination in the central area of Bristol, England, created by a gradual process of bridging and culverting over the diverted course of the River Frome.[1] The northern end of The Centre, known as Magpie Park, is skirted on its western edge by Colston Avenue; the southern end, the Centre Promenade, is a larger paved area bounded by St Augustine's Parade to the west, Broad Quay the east, and St Augustine's Reach (part of the Floating Harbour) to the south,[2].

The Centre has been altered on a number of occasions, initially to ease traffic flow[3][4] but latterly to try to strike a balance between its use as both a public open space and an important traffic corridor.[5] The most recent alterations to accommodate the MetroBus bus rapid transit scheme were completed in 2017.[6]

The name[edit]

The infilling of the northern part of St Augustine's Reach allowed for the creation of a paved triangular tram terminus. Various names were suggested for this, including St Augustine's Open Space, the Drawbridge, Colston's Cross or City Gardens, but the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company spurned these and adopted the name 'Tramways Centre',[7] which became shortened to 'The Centre'.[8] Although this name does not appear on conventional street maps it is widely understood locally,[9] and is used to refer to the open space in official documents such as the College Green Conservation Area Character Assessment.[10]

History[edit]

The Centre owes its form to a channel dug in the 1240s which diverted the River Frome to provide additional quays and wharves for the burgeoning Bristol Docks.[11] This channel, St Augustine's Reach, became the heart of the docks, but as these were expanded with the building of the Floating Harbour and Avonmouth Docks, the Drawbridge which crossed the Reach at the end of Clare Street and through which vessels passed to access the wharves at its northern end began to be seen as a source of "great congestion" to traffic.[12] This may be an understatement; it was often left open for twenty minutes while ships were roped up.[13]

Colston Avenue and 'Magpie Park'[edit]

In 1892 The Drawbridge was replaced by St Augustine's Bridge;[14] at the same time the docks to the north were infilled and the River Frome was arched over.[15] Under the Back, the road on the west side of this stretch of St Augustine's Reach, and Narrow Quay on the east side were replaced by a new road named Colston Avenue;[16] this encircled an open space which became known as named Magpie Park, after the newspaper The Bristol Magpie whose offices were located on the western side of Colston Avenue near Zed Alley.[17] The Bristol Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition was held here in 1893; this was a popular attraction which saw 500,000 attendees and raised £2200 for charity.[18] A drinking fountain near Colston's statue commemorates this exhibition.[19] Since 1932 this area has been the site of the Bristol Cenotaph,[20] the focus of local remembrance.[21]

Tramways Centre[edit]

During the 1890s, Bristol's tramway system was expanded and electrified. In 1896 the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company moved their head office to premises at 1–3 St Augustine's Parade, where they remained until 1970.[22] The need for a central interchange was recognised and to this end a large triangular traffic island, later nicknamed 'Skivvy's Island' because of its use by domestic servants,[23] was built between the BT&CC offices and St Augustine's Bridge.[24] The Tramways Centre became the most important of the BT&CC's three central termini, serving more routes than the others at Bristol Bridge and Old Market.[25] It was the terminus for trams from the north and east of the city, and trams from Hotwells to Temple Meads station and Brislington also stopped here. Passengers could straightforwardly alight from one tram and board another to continue their journey without the need to cross roads. A large three-faced ornamental clock was fixed high on the Tramways offices, and 'under the clock on The Centre' became a popular meeting place.[26][27]

J. B. Priestley visited Bristol in 1933, and described The Centre as 'a place where trams and coastal steamers seemed in danger of collision'.[28]

Buses first started to use the Tramways Centre in 1910,[29] initially only on the route to Clifton.[25] By 1913, ten bus routes started from The Centre.[30] In 1938 and 1939 the tram routes serving the Tramways Centre were replaced by buses,[31] so that trams ceased to use the island. Trams elsewhere in the city ceased completely in 1941.[32]

Inner Circuit Road[edit]

In 1936 construction started on a culvert covering the area between St Augustine's Bridge and the southern end of Broad Quay.[33] This created a route for the Inner Circuit Road, which had already bisected Queen Square, to continue northwards. Construction continued despite the outbreak of war. A large elongated roundabout was formed, with the central space initially being used as a car park.[34] The Tramways Centre island remained, devoid of trams.[3]

After the war the central space was planted with municipal lawns and ornamental flower beds and became known as the Centre Gardens.[35] Intrusive traffic, however, made it an obstacle to cross rather than a place to linger.[36]

1957 remodelling[edit]

The Inner Circuit Road was extended northwards into Colston Avenue in 1957–58. The Tramways Centre island was removed and the Centre Gardens island was extended to a point near the end of St Stephen's Street where a new road was cut across, reducing the length of Magpie Park and requiring the removal of a number of mature plane trees.[37]

1998 remodelling[edit]

It had been recognised since the 1960s that the southern half of the Inner Circuit Road had badly impacted the amenity of Queen Square and The Centre,[38] and by the 1990s tentative steps were being taken towards downgrading this part of the road and transferring traffic along less sensitive routes. By the mid-1990s, the road across Queen Square had been closed and plans were being developed to re-balance The Centre in favour of pedestrians and public transport. Bristol City Council launched a consultation exercise in 1996, in which the public were asked to choose between a 'Dock Option' (reopening the old harbour as far as St Augustine's Bridge) and a cheaper 'Promenade Option'. Both options involved closing the road across Quay Head; the Promenade Option used the new space to create a larger pedestrianised area in place of the Centre Gardens, with fountains, a cascade leading down to the waterside, and a sail structure to evoke Bristol's maritime past. The remaining road space in both options would be designed to give greater priority to public transport.[5]

Despite a strong local desire to reinstate the open waters of the River Frome,[9] the Council decided to build the 'Promenade Option'. This soon came under criticism for its poor safety, particularly after a number of pedestrians were injured by vehicles and at least two people struck by buses and killed.[39] The new design was also criticised for its traffic noise and fumes, "dribbling" fountains, poor traffic flow, poor cycling infrastructure, and delays to public transport.[40] Few were happy with the new design, and many were disappointed that the 'Dock Option' had not been pursued.[40]

The area around the pedestrian crossing at the Baldwin Street end of Broad Quay was altered in 2003 after the Bristol Coroner called for improvements.[41]

Despite remedial work in 2007, the sail structure was found to be unsafe and removed in 2009.[42]

2015 remodelling for MetroBus[edit]

Between 2015 and 2018 the layout of The Centre was changed once more, this time to accommodate the MetroBus bus rapid transit scheme.

Private motor traffic was routed along the western edge of The Centre, and the gyratory traffic system was replaced by extended and more accessible pedestrian spaces. The new layout reduced the number of routes available to general traffic, some of which was diverted away from the area, whilst improving segregation for cycles and buses.[6] The taxi ranks were relocated, new bus stops were constructed for MetroBus services, and Baldwin Street was extended across the Centre Promenade.[43]

Early indications suggest that journey times have been improved by these changes.[44]

Sites of interest[edit]

As well as the Cenotaph, Magpie Park has statues of MP Edmund Burke (1894)[45] and slave trader Edward Colston (1895, by John Cassidy).[46] St Mary on the Quay stands on Colston Avenue to the west of the park, and St Stephen's Church stands nearby to the east.

The southern end of The Centre (the Centre Promenade) has a 1723 lead statue of Neptune, moved to The Centre from Temple Street in 1949 and now Grade II* listed.[47][48] There is a modern water feature with fountains, and another stepped water feature leads down to a ferry landing stage at the current head of St Augustine's Reach. There is a busy taxi rank on Colston Avenue, near its junction with Baldwin Street.

On Broad Quay, the former head office tower of the Bristol and West Building Society has recently been refurbished as a hotel[49] and serviced flats.[50]

The Centre today[edit]

The Centre is not the historic centre of Bristol; the heart of the Saxon town lies at the crossroads of High Street, Wine Street, Corn Street and Broad Street.[51] Neither is it a major shopping area; the central shopping district is centred on Broadmead.[52] It is, however, an important local transport interchange and cultural destination.[53] Many local bus services terminate at or pass through here,[54] and it is also served by ferry services to Hotwells and Bristol Temple Meads station,[55] and has busy taxi ranks.[56]

Three of Bristol's major entertainment venues lie within a short distance of The Centre: The Hippodrome, still displaying nautical motifs reflecting the time when it faced onto the open waters of St Augustine's Reach, stands to the west of the Centre Promenade on St Augustine's Parade; the former Colston Hall, currently being refurbished,[57] is a few metres away on Colston Street, and the Theatre Royal is on nearby King Street.

The Centre is part of the College Green Conservation Area.[58]

Listed buildings[edit]

These listed buildings are located in The Centre:

| Number | Grade | Year listed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statue of Edmund Burke, Broad Quay | II | 1977 | Statue of Edmund Burke[45] |

| Statue of Edward Colston, Colston Avenue | II | 1977 | Statue of Edward Colston[59] |

| Drinking Fountain, Colston Avenue | II | 1977 | Drinking Fountain, Colston Avenue[19] |

| Cenotaph, Colston Avenue | II | 1977 | Cenotaph[20] |

| Cenotaph, Colston Avenue | II | 1977 | Four lamps approximately 4 metres from each corner of The Cenotaph[60] |

| West Gate, Colston Avenue | II | 1981 | West Gate[61] |

| 11 Small Street | II | 1975 | 11, Small Street[62] |

| Quay Head House, Colston Avenue | II | 1977 | Quay Head House[63] |

| 1, 3 and 5 St Stephens Street | II | 1994 | 1, 3 and 5, St Stephens Street[64] |

| 1, 2 and 3 Broad Quay | II | 1974 | 1, 2 and 3, Broad Quay[65] |

| 4 Broad Quay | II | 1974 | 4, Broad Quay[66] |

| 5 and 6 Broad Quay | II | 1974 | 5 and 6, Broad Quay[67] |

| 7 Broad Quay | II | 1974 | 7, Broad Quay[68] |

| Neptune statue, St Augustine's Quay | II* | 1959 | Neptune statue[47] |

| Attached wall, piers and gates to north of Transit Shed E | II | 1977 | Attached wall, piers and gates to north of Transit Shed E[69] |

Gallery[edit]

-

St Augustine's Reach, pre-1850, looking south across what is now Magpie Park

-

The Drawbridge, looking towards Clare Street and Baldwin Street

-

The Tramways Centre in the early 1900s

-

The Centre, 1958

-

Similar view of The Centre, 2005

-

The water fountains and paddling area in 2006, part of the 'Promenade Option'. The sail structure, removed in 2009, is shown behind

-

Magpie Park, before 2015 remodelling

-

Looking across newly-extended Baldwin Street into Clare Street, 2018

-

Magpie Park and St Stephen's St, 2018

-

St Mary on the Quay Church

References[edit]

Citations

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 30-31.

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 30.

- ^ a b Winstone 1980, Plate 15.

- ^ Winstone 1972, Plate 24.

- ^ a b Creating a new Centre for Bristol (leaflet), Bristol City Council, 1996

- ^ a b "New Bristol city centre road layout opens to traffic". BBC News. 2 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "The City Centre-Or is it?". About Bristol. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ^ Foyle 2004, p. 124.

- ^ a b Foyle 2004, p. 125.

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 16.

- ^ Appleby 1969, p. 10.

- ^ Winstone 1978, Plate 49.

- ^ Winstone 1973, Plate 31.

- ^ Winstone 1973, Plate 24.

- ^ Winstone 1978, p. 5.

- ^ Winstone 1973, Plate 12.

- ^ Winstone 1983, Plate 73.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Drinking Fountain, Colston Avenue (1202136)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Cenotaph (1372299)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Remembrance Day parades and services across greater Bristol area". Bristol Evening Post. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Appleby et al. 1974, p. 90-92.

- ^ Winstone 1977, Back cover.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

brokenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "BT&CC tram map, 1911". Bristol Vintage Bus Group. Retrieved 2 March 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Historic England. "Bristol Omnibus Company Travel and Chief Traffic Offices (1202525)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ^ "Britain at War: Devastated by friend's death". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ Priestley, J.B. (1934). English Journey. Mandarin. ISBN 978-0-7493-1924-3.

- ^ Hulin 1974, p. 3.

- ^ Hulin 1974, p. 4.

- ^ Hulin 1974, p. 9.

- ^ Appleby 1969, p. 65.

- ^ Winstone 1978a, Plates 30, 31, 33.

- ^ Winstone 1980, Plate 124.

- ^ Winstone 1980, Plate 12.

- ^ Eveleigh 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Winstone 1979a, Plates 169 and 173.

- ^ City centre policy report and map 1966. City of Bristol Printing and Stationery Department. 1966.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Is it time to drive cars out of Bristol City Centre? Bristol's traffic supremo believes so". Bristol Evening Post. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Bristol Central Area Action Plan: Cherish & Change summary". Bristol City Council. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Bristol centre to be revamped". BBC News. 15 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 December 2003. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Bristol city centre landmark has wind taken out of its sails". Bristol Evening Post. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "New city centre road layout". Travelwest. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ "City Centre Improvements". travelwest. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Statue of Edmund Burke (1282140)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 April 2018. Cite error: The named reference "nhburke" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

nhcolstonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Historic England. "Neptune Statue (1202528)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ "Statues and Sculptures – Introduction". About Bristol. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "From eyesore to Bristol icon". Bristol Evening Post. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Broad Quay Serviced Apartments, Bristol". activehotels. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Watts & Rahtz 1985, p. 16-17.

- ^ "Shops". Destination Bristol. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 19.

- ^ "Bus Departure Information" (PDF). Bristol City Council. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ^ "Ferry Map". Bristol Ferry Boat Co. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Map of Bristol city centre". Bristol City Council. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ "Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain's slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Insole & Porter 2016, p. 6.

- ^ Historic England. "Statue of Edward Colston (1202137)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Four lamps approximately 4 metres from each corner of The Cenotaph (1282344)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Historic England. "West Gate (1052272)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Historic England. "11, Small Street (1202578)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Historic England. "Quay Head House (1372267)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Historic England. "1, 3 and 5, St Stephens Street (1202559)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Historic England. "1, 2 and 3, Broad Quay (1282403)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Historic England. "4, Broad Quay (1281282)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Historic England. "5 and 6, Broad Quay (1202016)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Historic England. "7, Broad Quay (1281286)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ^ Historic England. "Attached wall, piers and gates to north of Transit Shed E (1202529)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

Sources

- Watts, Lorna; Rahtz, Philip (1985). Mary-le-Port Bristol Excavations 1962/3. City of Bristol Museums and Art Gallery. ISBN 0-900199-26-1.

- Hulin, P (1974). Bristol's Buses. Published by the author. ISBN 0-9503889-0-4.

- Appleby, John B (1969). Bristol's Trams Remembered. J.B. Appleby.

- Appleby, John B; Butcher, Edward W A; Gailey, T W H; Hulin, Peter; Mathieson, John; Urwin, Thomas J; Robinson, Philip A; Rootham, Bernard L; Wellman, Kenneth H (1974). The People's Carriage 1874-1974. Bristol Omnibus Company Ltd.

- Insole, Pete; Porter, Hannah (2016). "College Green-Conservation Area Character Appraisal". Bristol City Council.

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Pevsner Architectural Guides: Bristol. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10442-1.

- Eveleigh, David J (1998). Britain in Old Photographs-Bristol 1920-1969. Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-1907-8.

- Winstone, Reece (1970). Bristol's Earliest Photographs. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-42-X.

- Winstone, Reece (1983). Bristol as it Was 1845–1900. Reece Winstone. ISBN 978-0-900814-00-6.

- Winstone, Reece (1978). Bristol in the 1880s (2nd ed.). Reece Winstone. ISBN 978-0-900814-55-6.

- Winstone, Reece (1973). Bristol in the 1890s. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-42-X.

- Winstone, Reece (1977). Bristol in the 1920s. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-50-0.

- Winstone, Reece (1979). Bristol as it Was 1928–1933. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-57-8.

- Winstone, Reece (1978a). Bristol as it Was 1939–1914 (5th ed.). Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-54-3.

- Winstone, Reece (1980). Bristol in the 1940s (3rd ed.). Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-61-6.

- Winstone, Reece (1979a). Bristol as it Was 1953–1956 (2nd ed.). Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-56-X.

- Winstone, Reece (1972). Bristol as it Was 1956–1959. Reece Winstone. ISBN 0-900814-39-X.

Note: Hulin (1974) is textually similar to Appleby et al (1974), pp31-49; both sources are used as they are cited by different editors.

- Prince's Wharf, including M Shed, Pyronaut and Mayflower adjoining Prince Street Bridge

- Dry docks: SS Great Britain, the Matthew

- St Augustine's Reach, Pero's Bridge

- Bathurst Basin

- Queen Square

- Bristol Temple Meads railway station

- Castle Park

- Redcliffe Quay and Redcliffe Caves

- Baltic Wharf marina

- Cumberland Basin & Brunel Locks

- The New Cut

- Netham Lock, entrance to the Feeder Canal

- Totterdown Basin

- Temple Quay

- The Centre

- Canons Marsh, including Millennium Square and We The Curious

- Underfall Yard

- Bristol Bridge and Welsh Back