User:Pepperbeast/sandbox/thangching

Origin[edit]

Thangjing is a deity of pre-Hindu origin.[1][2][3][4][5] The Moirang Ningthourol Lambuba mentioned that Moirang was the amalgamation of different groups of people with different traditional beliefs. During the reign of King Fang Fang Ponglenhanpa (52 BC- 28 AD), all the diversities were merged into one with God Thangjing as the central figure.[6]

When the cult of Thangjing was merged into the Umang Laism, the folk deities associated with God Thangjing began to be identified with other Umang Lais. One example is that of goddess Ayang Leima Ahal and goddess Ayang Leima Atonpi. These two goddesses were originally associated with fertility and agriculture. This fact is evident in the ritualistic songs praising them. Later, these two female deities were identified as the consorts of God Thangjing.[6]

When Thangjing was identified as an Umang Lai, the identity of the two goddesses was associated with that of goddess Panthoibi. Thus, the new identity of Goddess Ayang Leima Panthoibi was formed.[6]

Description[edit]

Thangjing is described as the Lord of the tiger hunters.[7] The Moirang Ningthourol Lambuba describes God Thangjing as the Divine Chief of Koireng people, the Progenitor of Kege Clan, the Protector of all the domestic as well as wild animals and the Lord of Mahui tribe.[6]

The history of Moirang is always associated with the godly powers of Thangjing. Thangjing is a living God to the people of Ancient Moirang. The epic legend of the Khamba Thoibi is always related to God Thangjing. The ancient temple dedicated to Thangjing still stands on the banks of Loktak lake in the present day Moirang.[8][7]

Mythology[edit]

In the legendary epic Khamba Thoibi, Lord Thangjing always stands for righteousness and as a saviour of Khamba.[9]

Thangjing sent Phouoibi to Kege Moirang (Keke Moilang) to prosper the human world.[10]

When goddess Panthoibi was searching for her beloved Nongpok Ningthou, she asked God Thangjing and God Wangbren about the whereabouts of Nongpok Ningthou. To Thangjing, she said:

O! Thangjing, Supreme God of Moirang, Loktak is your mirror, My beloved Nongpok has gone like a wind, Like a cattle looking for its herd, I am looking for my beloved. Please tell me Does he come to your country?[11]

Worship[edit]

Thangching had been worshipped since ancient times. Still today, there is an ancient shrine at Moirang. An annual ritual festival known as Lai Haraoba is held early in summer in honor of the God.[12][13] During the annual Lai Haraoba festival, traditional dances and sports are performed as rituals. The performers follow the ancient customs of wearing the traditional attires of the royal lords and ladies.[3][4][14] The festival is celebrated during the Meitei lunar month of Kalen. It continues for a week.[15] Meiteis from all over Manipur visit the Thangjing Temple in Moirang.[16]

Namesakes[edit]

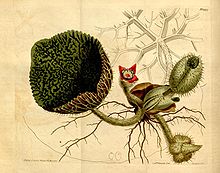

The Thangjing plant (Euryale ferox) is an aquatic plant that bears edible seeds. Its seeds are called "foxnuts" and are one of the most popular food items in Meitei cuisine of Manipur.[17][18]

The Thangching Peak (Thangjing Hill) is one of the four peaks, the others being the Koubru (after God Koubru), the Kounu (after Goddess Kounu) and the Loyalakpa (after God Loyalakpa). These peaks are the holy places of worship of the Meitei ethnicity. Their names are derived from the names of the deities whom the Meiteis worship at the peaks.[19]

See also[edit]

- Koupalu (Koubru) - north west protector

- Marjing - north east protector

- Wangbren - south east protector

References[edit]

- ^ Singh, A. Prafullokumar (2009). Elections and political dynamics. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-8324-279-0.

- ^ Laveesh, Bhandari (2009). Indian States At A Glance 2008-09: Performance, Facts And Figures - North-East And Sikkim. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-2348-7.

- ^ a b Singh, Arambam Sanatomba (2021-06-18). Ecotourism Development Ventures in Manipur: Green Skill Development and Livelihood Mission. Walnut Publication. ISBN 978-93-91145-59-0.

- ^ a b Kohli, M. S. (2002). Mountains of India: Tourism, Adventure and Pilgrimage. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-135-1.

- ^ Darpan, Pratiyogita (2008). Pratiyogita Darpan. Pratiyogita Darpan.

- ^ a b c d Birajit, Soibam (2014-12-01). Meeyamgi Kholao: Sprout of Consciousness. ARECOM ( Advanced Research Consortium, Manipur). p. 82.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

archive.orgwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Prakash 2007was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Singh, Rajkumar Mani (2002). Khwairakpam Chaoba Singh. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1519-1.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Session 1999was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Meitei, Mayanglambam Mangangsana (2021-06-06). The Sound of Pena in Manipur. Marjing Mayanglambam. ISBN 978-93-5473-655-1.

- ^ Devi, Dr Yumlembam Gopi. Glimpses of Manipuri Culture. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-0-359-72919-7.

- ^ Delhi, All India Radio (AIR), New (1967-12-03). AKASHVANI: Vol. XXXII, No.49 ( 3 DECEMBER, 1967 ). All India Radio (AIR),New Delhi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh, T. S. P. (2018-05-31). Apology. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5437-0188-3.

- ^ Gajrani, S. (2004). History, Religion and Culture of India. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8205-065-5.

- ^ Ghosh, G. K. (2002). Water of India: (quality and Quantity). APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7648-294-3.

- ^ "Thangjing". medicinalplants.co.in. May 2016.

- ^ "Thangjing – A potential aquatic cash crop in Manipur". e-pao.net.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Singhwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).