User:Pauloroboto/sandbox

Critique of political economy or critique of economy is a form of social critique that rejects the various social categories and structures which are constitutive of the contemporary form of resource allocation (ie "the economy"). Its adherents also tend to critique mainstream economists' use of what they believe are unduly unrealistic axioms, faulty historical assumptions, and the normative use of certain purportedly descriptive narratives. For example, they allege that economists tend to posit "the economy" as an a priori societal category.[1][2][3][4]

Those who engage in critique of economy tend to reject the view that the economy, is to be understood as something transhistorical,[5][6][7] but rather argue that it is a as relatively new mode of resource distribution which emerged along with modernity.[8][9][10] Therefore, the economy, is seen as merely one type of historically specific way to distribute resources.

Critics of economy critique the given status of the economy itself, and hence don't aim to create theories regarding how to administer economies.[3][11][1][4]

Critics of economy commonly view what is most commonly referred to as the economy as being bundles of metaphysical concepts, as well as societal and normative practices, rather than being the result of any "self-evident" or proclaimed "economic laws".[2][4][12] Hence they also tend to consider the views which are commonplace within the field of economics as faulty, or simply as pseudoscience.[13][14][15][16]

There are multiple critiques of political economy today, but what they have in common is critique of what critics of political economy tend to view as dogma, i.e. claims of "the economy" as a necessary and transhistorical societal category.[17][4]

Ruskin's critique of political economy[edit]

In the 1860s, John Ruskin published his essay Unto This Last which he came to view as his central work.[18][19][20] The essay was originally written as a series of publications in a magazine, which ended up having to suspend the publications, due to the severe controversy the articles caused.[19] While Ruskin is generally known as an important art critic, his study of the history of art was a component that gave him some insight into the pre-modern societies of the Middle Agesc, and their social organisation which he was able to contrast to his contemporary condition.[19][21] Ruskin attempted to mobilize a methodological/scientific critique of new political economy, as it was envisaged by the classical economists.[3]

Ruskin viewed "the economy" as a kind of "collective mental lapse or collective concussion", and he viewed the emphasis on precision in industry as a kind of slavery.[10][22] Due to the fact that Ruskin regarded the political economy of his time as "mad", he said that it interested him as much as "a science of gymnastics which had as its axiom that human beings in fact didn't have skeletons".[2] Ruskin declared that economics rests on positions that are exactly the same. According to Ruskin, these axioms resemble thinking, not that human beings do not have skeletons, but rather that they consist entirely of skeletons. Ruskin wrote that he didn't oppose the truth value of this theory, he merely wrote that he denied that it could be successfully implemented in the world in the state it was in.[2][19] He took issue with the ideas of "natural laws", "economic man" and the prevailing notion of "value" and aimed to point out the inconsistencies in the thinking of the economists.[3] As [3]well as critiqued Mill for thinking that ‘the opinions of the public’ was reflected adequately by market prices.[23]

Ruskin also coined the term 'Illth' to refer to unproductive wealth. Ruskin is not well known as a political thinker today but, when in 1906 a journalist asked the first generation of Labour MPs which book had most inspired them, Unto This Last emerged as an undisputed chart-topper.

[...] the art of becoming "rich," in the common sense, is not absolutely nor finally the art of accumulating much money for ourselves, but also of contriving that our neighbours shall have less. In accurate terms, it is "the art of establishing the maximum inequality in our own favour."

— Ruskin, Unto this last

Criticism of Ruskin's analysis[edit]

Marx and Engels regarded much of Ruskin's critique as reactionary. His idealisation of the Middle Ages made them reject him as a "feudal utopian".[19]

Marx's critique of political economy[edit]

| Part of a series on the |

| Marxian critique of political economy |

|---|

|

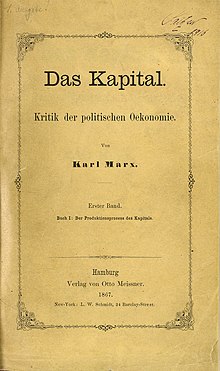

In the 21th century, Karl Marx is probably the most famous critic of political economy, with his three volume magnum opus Capital: A Critique of Political Economy as one of his most famous books.[26] However Marx's companion Friedrich Engels also engaged in critique of political economy in his 1844 Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy, which helped lay down some of the foundation for what Marx was to take further.[27][28][29] Marx's critique of political economy encompasses the study and exposition of the mode of production and ideology of bourgeois society, and its critique of Realabstraktionen ["real abstraction"], that is, the fundamental "economic", i.e., social categories present within what for Marx is the capitalist mode of production,[30][31] for example abstract labour.[clarification needed][32][4][33] In contrast to the classics of political economy, Marx was concerned with lifting the ideological veil of surface phenomena and exposing the norms, axioms, social relations, institutions and so on, that reproduced capital.[34]

The central works in Marx's critique of political economy are Grundrisse, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy and Das Kapital. Marx's works are often explicitly named – for example: A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, or Capital: A Critique of Political Economy.[35][26][17] Marx also cited Engels' article Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy several times in Das Kapital. However Trotskyists and other Leninists tend to implicitly or explicitly argue that these works constitute and or contain "economical theories" which can be studied independently.[36][37][38] This was also the common understanding of Marx's work on economy that was put forward by Soviet orthodoxy.[39][36] Since this is the case, it remains a matter of controversy whether Marx's critique of political economy is to be understood as a critique of the political economy or, according to the orthodox interpretation another theory of economics.[40][41] The critique of political economy is considered the most important and central project within marxism which has led to, and continues to lead to a large number of advanced approaches within and outside academic circles.[17][42][43]

Contemporary Marxian critique of political economy[edit]

Regarding contemporary Marxian critiques of political economy, these are generally accompanied by a rejection of more the more naturalistically influenced readings of Marx, as well as other readings later deemed weltanschaaungsmarxismus ("worldview marxism"),[44][39][45] that was popularised as late as toward the end of the 20th century.[44][11]

According to some scholars in this field, contemporary critiques of political economy and contemporary German Ökonomiekritik have been at least partly neglected in the anglophone world.[46]

Foundational concepts in Marx critique of political economy[edit]

- Labour and capital are historically specific forms of social relations, and labour is not the source of all wealth.[47][43][48]

- Labour is the other side of the same coin as capital, labour presupposes capital, and capital presupposes labour.[47][49]

- Money is not in any way something transhistorical or "natural" (which goes for the whole economy as well as the other categories specific to the mode of production), and gains its value/are constituted due to social relations rather than any inherent qualities.[47][50][51]

- The individual doesn't exist in some form of vacuum but is rather enmeshed in social relations.[52][53]

Marx critique of the quasi-religious and ahistorical methodology of economists[edit]

Marx described the view of contemporaneous economists and theologians on social phenomena as similarly unscientific.[54]

"Economists have a singular method of procedure. There are only two kinds of institutions for them, artificial and natural. The institutions of feudalism are artificial institutions, those of the bourgeoisie are natural institutions. In this, they resemble the theologians, who likewise establish two kinds of religion. Every religion which is not theirs is an invention of men, while their own is an emanation from God. When the economists say that present-day relations – the relations of bourgeois production – are natural, they imply that these are the relations in which wealth is created and productive forces developed in conformity with the laws of nature. These relations, therefore, are themselves natural laws independent of the influence of time. They are eternal laws that must always govern society. Thus, there has been history, but there is no longer any. There has been history, since there were the institutions of feudalism, and in these institutions of feudalism we find quite different relations of production from those of bourgeois society, which the economists try to pass off as natural and as such, eternal."

— Marx: The Poverty of Philosophy[16]

Marx continued to emphasize the ahistorical thought of the modern economists in the Grundrisse, where he among other endeavors, critiqued the liberal economist Mill.[4]

Marx also viewed the viewpoints which implicitly regarded the institutions of modernity as transhistorical as fundamentally deprived of historical understanding.[7][55]

Individuals producing in society, and hence the socially determined production of individuals, is, of course, the point of departure. The solitary and isolated hunter or fisherman, who serves Adam Smith and Ricardo as a starting point, is one of the unimaginative fantasies of eighteenth-century romances a la Robinson Crusoe; and despite the assertions of social historians, these by no means signify simply a reaction against over-refinement and reversion to a misconceived natural life. No more is Rousseau's contract social, which by means of a contract establishes a relationship and connection between subjects that are by nature independent, based on this kind of naturalism. [...] The individual in this society of free competition seems to be rid of natural ties, etc., which made him an appurtenance of a particular, limited aggregation of human beings in previous historical epochs. The prophets of the eighteenth century, on whose shoulders Adam Smith and Ricardo were still wholly standing, envisaged this 18th-century individual – a product of the dissolution of feudal society on the one hand and of the new productive forces evolved since the sixteenth century on the other – as an ideal whose existence belonged to the past. They saw this individual not as a historical result, but as the starting point of history; not as something evolving in the course of history, but posited by nature, because for them this individual was in conformity with nature, in keeping with their idea of human nature. This delusion has been characteristic of every new epoch hitherto.

— Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, (Introduction)

According to Jacques Rancière, what Marx understood, and what the economists failed to recognise was that the value-form is not something essential, but merely a part of the capitalist mode of production.[56]

On scientifically adequate research[edit]

Marx also offered a critique regarding the idea of people being able to conduct scientific research in this domain.[57] Or, as he stated it himself:

"In the domain of Political Economy, free scientific inquiry meets not merely the same enemies as in all other domains. The peculiar nature of the materials it deals with, summons as foes into the field of battle the most violent, mean, and malignant passions of the human breast, the Furies of private interest. The English Established Church, e.g., will more readily pardon an attack on 38 of its 39 articles than on 1/39 of its income. Nowadays atheism is culpa levis [a relatively slight sin, c.f. mortal sin], as compared with criticism of existing property relations."

— Marx: Das Kapital (Preface to the First German Edition)

On vulgar economists[edit]

Marx also used to criticize the false critique of political economy of his contemporaries. Something he did, sometimes even more forcefully, than he critiqued the classical, and hence 'vulgar' economists. He for example rejected Lasalle's 'iron and inexorable law' of wages, which he simply regarded as mere phraseology.[58] As well as Proudhon's attempts to do what Hegel did for religion, law, etc., for political economy, as well as regarding what is social as subjective, and what was societal as merely subjective abstractions.[59][47] In Marx's view, the errors of these authors led the workers' movement astray.

Interpretations of Marx's critique of political economy[edit]

Some scholars view Marx's critique as being a critique of commodity fetishism and the manner in which this concept expresses a criticism of modernity and its modes of socialisation.[60] Other scholars who engage with Marx's critique of political economy affirm the critique might assume a more Kantian sense, which transforms "Marx's work into a foray concerning the imminent antinomies that lie at the heart of capitalism, where politics and economy intertwine in impossible ways."[17]

Contemporary scholarship[edit]

Baudrillard[edit]

The sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard has developed a critique of Marx's political economy in his 1973 book Le Miroir de la production. He views Marx as being stuck in the very categories he wanted to critique, in particular production.[61][62] In contrast to this, Baudrillard rather places emphasis on consumption.[63] Baudrillard claims that the structure of every sign is ingrained in every core of the commodity form. He claims that it establishes itself socially, as a total medium, a system which administers all social exchange.[64] In Baudrillard's words, “[Marxism] convinces men that they are alienated by the sale of their labor power, thus censoring the [...] hypothesis that they might be alienated as labor power.”[65]

Fisher[edit]

Mark Fisher critiqued economics, claiming that is was a bourgeois "science", that molded reality after its presuppositions, rather than critically examined reality. As he stated it himself:

"From the start, “economy” was the object-cause of a bourgeois “science”, which hyperstitionally bootstrapped itself into existence, and then bent and melted the matter of this and every other world to fit its presuppositions — the greatest theocratic achievement in a history that was never human, an immense conjuring trick which works all the better because it came shrouded in that damp grey English and Scottish empiricism which claimed to have seen off all gods."[66]

Feminist critique of political economy[edit]

There has been a growing literature of feminist viewpoints in new critique of political economy in recent years.[67][68][69]

Differences between critics of economy and critics of economical issues[edit]

One may differentiate between those who engage in critique of political economy, which takes on a more ontological character, where authors criticise the fundamental concepts and social categories which reproduce the economy as an entity.[2][70][1][71][4] While other authors, which the critics of political economy would consider only to deal with the surface phenomena of "the economy", have a naturalized understanding of these social processes.

Hence the epistemological differences between critics of economy and economists can also at times be very large.[4]

In the eyes of the critics of political economy, the critics of economic issues merely critique "certain practices" in attempts to implicitly or explicitly 'rescue' the political economy; these authors might for example propose universal basic income or to implement a planned economy.[70][72][36][11]

List of critics of political economy[edit]

Contemporary[edit]

Sociologists[edit]

- Orlando Patterson, John Cowles professor of sociology at Harvard University has claimed that economics is a pseudoscience.[73]

Philosophers[edit]

Historians[edit]

Historical[edit]

Historians[edit]

Poets[edit]

Others[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b c Ruccio, David (10 December 2020). "Toward a critique of political economy | MR Online". mronline.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

Marx arrives at conclusions and formulates new terms that run directly counter to those of Smith, Ricardo, and the other classical political economists.

- ^ a b c d e Ruskin, John. Unto this Last. pp. 128–129.

Observe, I neither impugn nor doubt the conclusions of the science if its terms are accepted. I am simply uninterested in them, as I should be in those of a science of gymnastics that assumed that men had no skeletons. It might be shown, on that supposition, that it would be advantageous to roll the students up into pellets, flatten them into cakes, or stretch them into cables; and that when these results were effected, the re-insertion of the skeleton would be attended with various inconveniences to their constitution. The reasoning might be admirable, the conclusions true, and the science deficient only inapplicability. Modern political economy stands on a precisely similar basis. Assuming, not that the human being has no skeleton, but that it is all skeleton, it founds an ossifiant theory of progress on this negation of a soul; and having shown the utmost that may be made of bones, and constructed a number of interesting geometrical figures with death's-heads and humeri, successfully proves the inconvenience of the reappearance of a soul among these corpuscular structures. I do not deny the truth of this theory: I simply deny its applicability to the present phase of the world.

- ^ a b c d e Henderson, Willie (2000). John Ruskin's political economy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-15946-2. OCLC 48139638.

[...]Ruskin attempted a methodological/scientific critique of political economy. He fixed on ideas of 'natural laws', 'economic man' and the prevailing notion of 'value' to point out gaps and inconsistencies in the system of classical economics.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Louis, Althusser; Balibar, Etienne (1979). Reading Capital. Verso Editions. p. 158. OCLC 216233458.

[...] 'to criticize' Political Economy cannot mean to criticize or correct certain inaccuracies or points of detail in an existing discipline nor even to fill in its gaps, its blanks, pursuing further an already largely initiated movement of exploration. 'To criticize Political Economy' means to confront it with a new problematic and a new object: i.e., to question the very object of Political Economy. But since Political Economy is defined as Political Economy by its object, the critique directed at it from the new object with which it is confronted could strike Political Economy's vital spot. This is indeed the case: Marx's critique of Political Economy cannot challenge the latter's object without disputing Political Economy itself, in its theoretical pretensions to autonomy and in the 'divisions' it creates in social reality in order to make itself the theory of the latter. [...] it queries not only the object of Political Economy, but also Political Economy itself as an object. [...] Political Economy, as it is defined by its pretensions, has no right to exist as far as Marx is concerned: if Political Economy thus conceived cannot exist, it is for de jure, not de facto reasons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Fareld, Victoria; Kuch, Hannes (2020), From Marx to Hegel and Back, Bloomsbury Academic, p. 182, doi:10.5040/9781350082700.ch-001, ISBN 978-1-3500-8267-0, S2CID 213805975, retrieved 17 September 2021

- ^ Postone 1993, pp. 44, 192–216.

- ^ a b Ruccio, David (10 December 2020). "Toward a critique of political economy | MR Online". mronline.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

Second, Marx's concern is always with social and historical specificity, as against looking for or finding what others would consider being given and universal.

- ^ Chouquer, Gérard (1 January 2002). "Alain Guerreau, L'avenir d'un passé incertain. Quelle histoire du Moyen Âge au XXIesiècle? Paris, Le Seuil, 2001". Études rurales (161–162). doi:10.4000/etudesrurales.106. ISSN 0014-2182.

- ^ Moishe., Postone (1995). Time, labor, and social domination : a reinterpretation of Marx's critical theory. pp. 130, 5. ISBN 0-521-56540-5. OCLC 910250140.

- ^ a b Jönsson, Dan. "John Ruskin: En brittisk 1800-talsaristokrat för vår tid? - OBS". sverigesradio.se (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

Den klassiska nationalekonomin, som den utarbetats av John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith och David Ricardo, betraktade han som en sorts kollektivt hjärnsläpp ... [Transl. Ruskin viewed the classical political economy as it was developed by Mill, Smith, and Ricardo, as a kind of "collective mental lapse.]

- ^ a b c Ramsay, Anders (21 December 2009). "Marx? Which Marx? Marx's work and its history of reception". www.eurozine.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

When it is based on the naturalistic understanding, the entire theoretical edifice of the critique of political economy breaks down. What is left is a theory not entirely unlike Adam Smith's, one in which individual labour creates value, and the capacity to create value becomes an ontological determination of labour. With good reason, one could speak of a Smithian Marxism ...

- ^ Peperell, Nicole. "Beyond reification: Reclaiming Marx's Concept of the Fetish Character of the Commodity" (PDF). Kontradikce: A Journal for Critical Thought.

The critical edge of Marx's analysis does not derive, therefore, from any sort of declaration that this impersonal social relation does not exist, or is not 'truly' impersonal. Instead, it derives from the demonstration of how such a peculiar and counter-intuitive sort of social relation – one that possesses qualitative characteristics more normally associated with our interactions with non-social reality – comes to be unintentionally generated in collective practice.

- ^ Patterson, Orlando; Fosse, Ethan. "Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015.

[...] the real-world implementation of mainstream economic ideas has been a string of massive failures. Economic thinking undergirded the "deregulation" mantra leading up to the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and has fared no better in attempts to "fix" the ongoing crisis in Europe. [...] nowhere is the discipline's failure more apparent than in the area of development economics. In fact, the only countries that have effectively transformed from the "Third" to the "First World" since World War II violated the main principles of current and previous economic orthodoxies: [...] Only recently have economists come to accept the primacy of institutions in explaining and promoting economic growth, a position long held by sociologists [...]

(OpEd) - ^ Badeen, Dennis; Murray, Patrick. "A Marxian Critique of Neoclassical Economics' Reliance on Shadows of Capital's Constitutive Social Forms" (PDF). crisiscritique.org.

- ^ Murray, Patrick (March 2020). "The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms". Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1086/708005. ISSN 2326-4462. S2CID 219746578.

"Bourgeois or capitalist production . . . is consequently for [Ricardo]," Marx writes, "not a specific definite mode of production, but simply the mode of production." [...] The illusion of the economic arises within what Marx calls the "bourgeois horizon," which trades in phenomenologically false bifurcations such as the purely subjective versus the purely objective, form versus content, forces versus relatisusons of production, the labor process versus the valorization process, distribution versus production, and more.

- ^ a b "The Poverty of Philosophy - Chapter 2.1". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ruda, Frank; Hamza, Agon (2016). "Introduction: Critique of Political Economy" (PDF). Crisis and Critique. 3 (3): 5–7.

- ^ Ruskin, John (1877). Unto This Last, and Other Essays on Political Economy. Sunnyside, Orpington, Kent: George Allen – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d e Jönsson, Dan. "John Ruskin: En brittisk 1800-talsaristokrat för vår tid? - OBS". sverigesradio.se (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Swann, G M Peter (2001). ""No Wealth But Life": When Does Mercantile Wealth Create Ruskinian Wealth?" (PDF). European Research Studies Journal. IV (3–4): 5–18.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Ruskin the radical: why the Victorian critic is back with a vengeance". The Guardian. 30 August 2018. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

"In some ways, Ruskin seems like the most Victorian of the Victorians, so not applicable to our lives now," says David Russell, associate professor of English at Corpus Christi College Oxford. "People get hung up on how eccentric some of his ideas were, but the core of his claims remains relevant and important. That is to say: our aesthetic experience, our experience of beauty in ordinary life, must be central to thinking about any good life and society. It's not just decoration or luxury for the few. If you are taught how to see the world properly through an understanding of aesthetics, then you'll see society properly."

- ^ "From Labor to Value: Marx, Ruskin, and the Critique of Capitalism". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Willie (2000). John Ruskin's political economy. London: Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 0-203-15946-2. OCLC 48139638.

Ruskin's criticism of Mill is that he based the science of political economy on 'the opinions of the public' as expressed by market prices, i.e. on 'fuddled' thought induced by contemplating the shadow of value rather than thinking upon, by implication, a true (Platonic) object of cognition.

- ^ "Gandhi's Human Touch | Articles on and by Mahatma Gandhi". www.mkgandhi.org. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1867–1894). Das Kapital : Kritik der politischen Ökonomie [Capital: A Critique of Political Economy]. ISBN 978-3-7306-9034-5. OCLC 1141780305.

- ^ a b Conttren, V. (2022). "István Mészáros: The Critique of Political Economy". Conttren, V. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/65MXD.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Deutsch-Franzosische Jahrbucher" [German-French Yearbooks]. www.marxists.org. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Liedman, Sven-Eric. "Engelsismen" (PDF). Fronesis (in Swedish) (28): 134.

Engels var också först med att kritiskt bearbeta den nya nationalekonomin; hans "Utkast till en kritik av nationalekonomin" kom ut 1844 och blev en utgångspunkt för Marx egen kritik av den politiska ekonomin

[Engels was the first to critically engage the new political economy his Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy came out in 1844 and became a starting point for Marx's own critique of the political economy] - ^ Murray, Patrick (March 2020). "The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms". Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1086/708005. ISSN 2326-4462. S2CID 219746578.

"There are no counterparts to Marx's economic concepts in either classical or utility theory." I take this to mean that Marx breaks with economics, where economics is understood to be a generally applicable social science.

- ^ "Marx Ekonomikritik". Fronesis (in Swedish) (28). Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Bellofiore, Riccardo (2016). "Marx after Hegel: Capital as Totality and the Centrality of Production" (PDF). Crisis & Critique. 3 (3): 31.

- ^ Jung, Henrik (1 January 2019). "Slagen av abstraktioner: Förnuftiga och reala abstraktioner i Marx ekonomikritik". Lychnos: Årsbok för idé- och lärdomshistoria (in Swedish). ISSN 0076-1648.

Marx consistently reveals the social abstraction of the substance of value and capital, i.e. abstract labour, as a Realabstraktion dominating individuals in bourgeois society through money and capital.

- ^ Fareld, Victoria; Kuch, Hannes (9 January 2020). From Marx to Hegel and back capitalism, critique, and utopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 150, 143. ISBN 978-1-350-08268-7. OCLC 1141198381.

- ^ Freeman, Alan. "The psychopathology of Walrasian Marxism" (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2018.

'Economic' categories, appearing as inhuman things with a mind of their own – prices, money, interest rates – are for Marx the disguised form of relations between people.

- ^ Balibar, Étienne (2007). The philosophy of Marx. London: Verso. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84467-187-8. OCLC 154707531.

The expression 'critique of political economy' figures repeatedly in the title or programme of Marx's main works [...] To these we may add a great many unpublished pieces, articles and sections in polemical works.

- ^ a b c Volkov, Genrikh Nikolaevich (1982). The Basics of Marxist-Leninist Theory. Progress guides to the social sciences. Moscow: Progress. pp. 51, 188, 313. OCLC 695564556.

- ^ Ernest, Mandel (1973). An introduction to Marxist economic theory. Pathfinder. ISBN 0-87348-315-4. OCLC 609440295.

- ^ Brooks, Mick. "An introduction to Marx's Labour Theory of Value". In Defence of Marxism. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b Ramsay, Anders. "Marx? Which Marx? Marx's work and its history of reception". www.eurozine.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

During a second phase, a less "economistic" Marx emerged. The publication of the writings of the young Marx, above all the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, revealed a different Marx, one less preoccupied with technology, and less deterministic. It became possible to criticise "Marx through Marx", a critique which had particular importance in the eastern European state socialist systems.

- ^ "Excerpt from discussion on SPSM listserv on whether Capital can be understood as a "Critique" of Political economy or as "Marxist" political economy, highlighting the view of Juan Inigo". www.marxists.org.

- ^ Wolff, Jonathan; Leopold, David (2 September 2021). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "Programme of the French Worker's Party". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b Postone 1993.

- ^ a b "Läs kapitalet - igen" [Capital - again] (PDF). Fronesis. 28: 12 (p.5 in the pdf). [His striving to develop a materialist ontology and a unitary theory, which could speak on all parts of reality, made a wider use for the schools and parties in the east which far into the sixties and seventies stood for different forms of worldview marxism.]

- ^ "Läs kapitalet - igen" [Read Capital - again] (PDF). Fronesis. 28: 10 (p.3 in the pdf).

- ^ O’Kane, Chris (29 January 2018). "On the Development of the Critique of Political Economy as a Critical Social Theory of Economic Objectivity: A Review of Critical Theory and the Critique of Political Economy by Werner Bonefeld". Historical Materialism. 26 (1): 175–193. doi:10.1163/1569206X-12341552. ISSN 1465-4466.

[...] a number of important critical- theoretical approaches to the critique of political economy [...] have been largely neglected in the anglophone world.

- ^ a b c d Marx, Karl; Nicolaus, Martin (1993). Grundrisse : foundations of the critique of political economy (rough draft). London: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review. pp. 296, 239, 264. ISBN 0-14-044575-7. OCLC 31358710.

- ^ "Marx's Critique of Classical Economics". www.marxists.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2001. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

These points made here by Marx are particularly important in view of the fact that it is almost a commonplace amongst those sympathetic to, as well as those hostile to, Marx to assume that he shared a basically similar value theory with that of his classical forerunners, namely a labour theory of value. I believe, however, this notion – of a 'labour theory of value' in Marx – is at best confusing and at worst quite wrong.

- ^ Pradella, Lucia (2015). Globalisation and the critique of political economy : new insights from Marx's writings. Abingdon, Oxon. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-317-80072-9. OCLC 897376910.

The analysis of the production process as a whole, namely, as a reproduction process, removed the illusion of the autonomy of value, revealing that capital entirely consists of objectified labour. Workers are faced with their own labour, objectified in means of production and of subsistence, which becomes capital, thus recreating the conditions for their exploitation.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Saitō, Kōhei (2017). Karl Marx's ecosocialism: capitalism, nature, and the unfinished critique of political economy. New York. ISBN 978-1-58367-643-1. OCLC 1003193200.

Marx's critique of classical political economy as a critique of the fetishistic (that is, ahistorical) understanding of economic categories, which identifies the appearance of capitalist society with the universal and transhistorical economic laws of nature. Marx, in contrast, comprehends those economic categories as "specific social forms" and reveals the underlying social relations that bestow an objective validity of this inverted world where economic things dominate human beings.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Behrens, Diethard (1993). Gesellschaft und Erkenntnis. Freiburg i. Br.: Ça ira. pp. 71–72. ISBN 3-924627-34-7. OCLC 30457885.

- ^ Marx, Karl. "Economic Manuscripts: Appendix I: Production, Consumption, Distribution, Exchange". www.marxists.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2002. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

Individuals producing in society, and hence the socially determined production of individuals, is, of course, the point of departure. The solitary and isolated hunter or fisherman, who serves Adam Smith and Ricardo as a starting point, is one of the unimaginative fantasies of eighteenth-century romances a la Robinson Crusoe [...] The prophets of the eighteenth century, on whose shoulders Adam Smith and Ricardo were still wholly standing, envisaged this 18th-century individual [...] They saw this individual not as a historical result, but as the starting point of history; not as something evolving in the course of history, but posited by nature, because for them this individual was in conformity with nature, in keeping with their idea of human nature. This delusion has been characteristic of every new epoch hitherto. [...]

The further back we trace the course of history, the more does the individual, and accordingly also the producing individual, appears to be dependent and to belong to a larger whole. [...] It is not until the eighteenth century that in bourgeois society the various forms of the social texture confront the individual as merely means towards his private ends, as external necessity. But the epoch which produces this standpoint, namely that of the solitary individual, is precisely the epoch of the (as yet) most highly developed social (according to this standpoint, general) relations. Man [...] is not only a social animal but an animal that can be individualised only within society. - ^ Marx, Karl. "Critique of the Gotha Programme-- I". www.marxists.org. Archived from the original on 23 August 2002. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

Thirdly, the conclusion: "Useful labor is possible only in society and through society, the proceeds of labor belong undiminished with equal right to all members of society." A fine conclusion! If useful labor is possible only in society and through society, the proceeds of labor belong to society [...] The first and second parts of the paragraph have some intelligible connection only in the following wording: "Labor becomes the source of wealth and culture only as social labor", or, what is the same thing, "in and through society".

- ^ Peperell (2018). "Beyond reification: Reclaiming Marx's Concept of the Fetish Character of the Commodity" (PDF). Kontradikce: A Journal for Critical Thought. 2: 35.

[...] it becomes clearer that Marx intends to draw a distinction between social phenomena that could either be understood purely in cultural terms or solely in terms of intersubjectively-meaningful social phenomena, and a different kind of social phenomenon, one that Marx suggests social actors can create unintentionally, prior to integrating it into meaningful intersubjective belief systems. This distinction becomes important to Marx's claim that political economy only retroactively discovers certain social patterns that Marx regards as intrinsic to capitalist production, and is important to understanding why Marx's concept of the fetish is distinct from many attempts to thematize ideology, which often understand ideology in terms of false consciousness or incorrect belief.

- ^ Duarte, Filipe (4 February 2019). "Marx's method of political economy". Progress in Political Economy (PPE). Retrieved 14 February 2022.

Social phenomena exist, and can be understood, only in their historical context.

- ^ Rancière, Jacques (August 1976). "The concept of 'critique' and the 'critique of political economy' (from the 1844 Manuscript to Capital)". Economy and Society. 5 (3): 352–376. doi:10.1080/03085147600000016. ISSN 0308-5147 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1887) [1867]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (PDF). Vol. I: The Process of Production of Capital – via www.marxists.org.

- ^ Bellofiore, Riccardo, ed. (27 May 2009). Rosa Luxemburg and the Critique of Political Economy. Routledge. p. 161. doi:10.4324/9780203878392. ISBN 978-1-134-13507-3.

- ^ "The Poverty of Philosophy - Chapter 2.1". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Pimenta, Tomás Lima (August 2020). "Alienation and fetishism in Karl Marx's critique of political economy". Nova Economia. 30 (2): 605–628. doi:10.1590/0103-6351/4958. ISSN 1980-5381.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean (1975). The mirror of production. p. 17. ISBN 0-914386-06-9.

- ^ Baudrillard. "Arbete". Fronesis. 9–10: 149–170.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean (1975). The mirror of production. St. Louis: Telos Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-914386-06-9. OCLC 2192359.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean (1981). For a critique of the political economy of the sign. Telos press. p. 146.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean (1975). The mirror of production. St. Louis: Telos Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-914386-06-9. OCLC 2192359.

- ^ Fisher, Mark (2018). K-punk : the collected and unpublished writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016). Darren Ambrose, Simon Reynolds. London, UK. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-912248-28-5. OCLC 1023859141.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). The end of capitalism (as we knew it) : a feminist critique of political economy (First University of Minnesota Press ed.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-9844-8. OCLC 218708717.

- ^ Scholz, Roswitha (2013). "Patriarchy and Commodity Society: Gender Without the Body". Mediations. 27 (1–2).

- ^ Dimitrakaki, Angeliki (4 May 2018). "Feminism and the Critique of the Political Economy of Art".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Henderson, Willie (2000). John Ruskin's political economy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-15946-2. OCLC 48139638.

It could be argued that Ruskin, like Plato, is addressing the problems of society as a whole rather than addressing economic issues. Nonetheless, he approaches such concerns through a critique of political economy.

- ^ Arthur, Christopher (2004). The new dialectic and Marx capital. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 232–233, 8.

- ^ Ayres, Robert (12 August 2020). "How Universal Basic Income Could Save Capitalism". INSEAD Knowledge. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Patterson, Orlando; Fosse, Ethan (9 February 2015). "Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics". www.nytimes.com. (OpEd)

- ^ Fisher, Mark (13 November 2018). K-punk. pp. 605–607. ISBN 9781912248292.

- ^ Hamza, Agon. "Re-reading Capital 150 years after: some Philosophical and Political Challenges" (PDF). Continental Thought & Theory: A Journal of Intellectual Freedom: 158–159.

This is the Žižekian lesson: Marx's critique of political economy is not only a critique of the classical political economy (Smith, Ricardo...), but it is also a form of critique, a transcendental one according to Žižek, which allows us to articulate the elementary forms of social edifice under capitalism itself. And this 'transcendental' framework, cannot be other than philosophical.

- ^ Broady, Donald (1978) (http://www.skeptron.uu.se/broady/arkiv/dba-b-19780002-broady-aterupptackten-faksimil.pdf)

- ^ "Litteraturens värden - Lunds universitet" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Vad är ekonomi?-citat". citatboken.se (in Swedish).

- ^ "Rätten till lättja". Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Postone, Moishe (1993). Time, Labor and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521391573. OCLC 231578868.

- Johnsdotter S, Carlbom A, editors. Goda sanningar: debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Lund: Nordic Academic Press; 2010.

- Braudel F. Kapitalismens dynamik. (La Dynamique du Capitalisme) [Ny utg.]. Göteborg: Daidalos; 2001.

- Ankarloo D, editor. Marx ekonomikritik. Stockholm: Tidskriftsföreningen Fronesis; 2008.

- Eklund K. Vår ekonomi: en introduktion till världsekonomin. Upplaga 15. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2020.

- Tidskriftsföreningen Fronesis. Arbete. Stockholm: Tidskriftsfören. Fronesis; 2002.

- Baudrillard J. The Mirror of Production. Telos Press; 1975.

- Marx K. Till kritiken av den politiska ekonomin. [Ny utg.]. Göteborg: Proletärkultur; 1981.

Further reading[edit]

Articles[edit]

General articles[edit]

- (In Swedish) - Mortensen, Anders - Att göra "penningens genius till sin slaf". Om Carl Jonas Love Almqvists romantiska ekonomikritik - Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund. Årsbok.

Scholarly articles[edit]

- Granberg, Magnus "Reactionary radicalism and the analysis of worker subjectivity in Marx’s critique of political economy"

Books[edit]

Critique of political economy[edit]

- Baudrillard, Jean - The Mirror of Production

- Baudrillard, Jean - For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. - The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy

- Bernard Steigler - For a New Critique of Political Economy

On Marx critique of political economy[edit]

- Murray, Patrick (2016), The mismeasure of wealth - Essays on Marx and social form. - Brill

- Pepperell, Nicole (2010), Disassembling Capital, RMIT University

- Postone, Moishe (1993) - Time labour and social domination

Neue Marx-Lektüre[edit]

- Elbe, Ingo (2010). Marx Im Westen. Die neue Marx-Lektüre in der Bundesrepublik seit 1965 [Marx in the west. The new reading of Marx in the Federal Republic since 1965]. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. ISBN 9783050061214. OCLC 992454101.

History[edit]

- Bryer, Robert - Accounting for History in Marx's Capital: The Missing Link

- Kurz, Robert, 1943-2012, Schwarzbuch Kapitalismus: ein Abgesang auf die Marktwirtschaft (also known as: The Satanic Mills) - 2009 - Erweit. Neuasg. ISBN 978-3-8218-7316-9

- Pilling, Geoff - Marx's Capital, Philosophy and Political Economy

Classic works[edit]

- Lietz, Barbara (1987). "Ergänzungen und Veränderungen zum ersten Band des Kapitals (Dezember 1871 - Januar 1872)" [Additions and changes to the first volume of Das Kapital (December 1871 - January 1872)]. Marxistische Studien: Jahrbuch des IMSF. Vol. 12. p. S. 214–219. OCLC 915229108.

- Marx, Karl - Grundrisse

- Ruskin, John, Unto this Last LibriVox.

Essays[edit]

- Postone, Moishe - Necessity, Labor and Time: A Reinterpretation of the Marxian Critique of Capitalism

External links[edit]

- 1995-2004 Conference Papers - Critique Of Political Economy / International Working Group on Value Theory (COPE- IWGVT)

- A collection of material related to Marx critique of political economy

- Critique of Political Economy - a 2016 edition of the philosophy journal: crisis and critique

- Postone, Moishe (Fall 2015). Capitalism, Temporality, and the Crisis of Labor. Ellen Maria Gorrissen lectures. (A lecture regarding Marx's critique of political economy.)

- Translated texts from a contemporary German group critical of political economy.

Critique of political economy or critique of economy is a form of social critique that aims to reject the various social categories and structures that constitute the contemporary forms and modalities of resource allocation (i.e. "the economy") in its entirety. Those who critique the economy in this way also tend to critique economists' use of what they believe are unduly unrealistic axioms, faulty historical assumptions, and the normative use of certain purportedly descriptive narratives.[1] As well as commonly allege that economists tend to posit the economy as an a priori societal category.[2][3][4]

Those who engage in critique of economy tend to reject the view that the economy, and its categories, is to be understood as something transhistorical.[5][6] They rather argue that it is a relatively new mode of resource distribution, which emerged along with modernity.[7][8][9] Hence, it is seen as merely one of many types of historically specific ways to distribute resources.

Since critics of the economy critique the given status of the economy itself, they don't aim to create theories regarding how to administer economies.[1][10][11][4]

Critics of economy commonly view what is most commonly referred to as the economy as being the result of societal, normative and metaphysical practices, rather than being the result of any "self-evident" or proclaimed "economic laws".[2][4][12] Hence they also tend to consider the views which are commonplace within the field of economics as faulty, or simply as normative pseudoscience.[13][14][3][15]

There are multiple critiques of political economy today, but what they have in common is critique of what critics of political economy tend to view as dogma, i.e. claims of "the economy" as a necessary and transhistorical societal category.[16]

__

critics of political economy, sociologists, philosophers, economists etc.[17][18][19][20] Not seldom due to what's claimed to be unduly unrealistic axioms, faulty historical assumptions, dogma, as well as a general lack of concern of being scientific.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27] But some authors also claimed econo

mics to have a fundamentally ontologically inverted relationship to empirical reality.[28] For example due to a conceptual apparatus that is claimed to not correspond with reality.[28]

Examples:

- Economists critique of unfalsifiable theories such as general equilibrium theory.[29]

- Very" heterodox usage" of conventional methodology, where models are "calibrated", to guarantee that the models mimics the data.[27]

- Economists such as John Weeks, Michael Perelman, has also stated that that economic theory ofte

- n don't correspond with reality at all, and or is simply to be regarded as pseudoscience.[30][20]

- Critics of economics have also used more blunt language. For example Engels claim that economics as a system of licensed fraud.[31] As well as Kropotkins assertion that economics is the pseudoscience of the bourgeoisie.[32]

- mathiness.

Kahneman claimed "highly experienced financial managers" in fact performed 'no better than chance', the "illusion of skill".[33]

Bar[27][20][17][18][34][35][21]

käb

Capital[edit]

- Wage-labour is the basic "cell-form" (trade unit) of modern society. Moreover, because commerce as a human activity implied no morality beyond that required to buy and sell goods and services, the growth of the market system made discrete entities of the economic, the moral, and the legal spheres of human activity in society; hence, subjective moral value is separate from objective economic value. Subsequently, political economy (the just distribution of wealth) and "political arithmetic" (about taxes) were reorganized into three discrete fields of human activity, namely economics, law and ethics—politics and economics were divorced.

- "The economic formation of society [is] a process of natural history". Thus, it is possible for a economist to study administration of the modern epoch, given that its expansion of the market system of commerce has objectified human (economic) relations. The use of money (cash nexus) voided religious and political illusions about its economic value and replaced them with commodity fetishism, the belief that an object (commodity) has inherent economic value. Because societal economic formation is a historical process, no one person could control or direct it, thereby creating a global complex of social connections.

Economics has been claimed to be a pseudoscience by a minority of scholars for the absolute majority of its history.[41] However, many economists dispute this.[42][43] There is also others scholars who don't view economics as a discipline as pseudo-scientific, but are concerned with issues like unfalsifiable theories, scientism, questionable research methods etc.[44][45]

- The structural contradictions in the economic system (German: gegensätzliche Bewegung) describe the contradictory movement originating from the two-fold character of labour. These economic contradictions operate "behind the backs" of the owners of capital, and the workers as a result of their activities, and yet remain beyond their immediate perceptions.

- The crises (recession, depression, et cetera) that are rooted in the contradictory character of the commodity (cell-unit) of modern society.

- In the mode of production where labour and capital are the axioms, technological improvement and its consequent increased production augment the amount of material wealth (use value) in society while simultaneously diminishing the economic value of the same wealth, thereby diminishing the rate of profit—a paradox characteristic of crisis in a capital economy. "Poverty in the midst of plenty" consequent to over-production and under-consumption.

OTHER:[edit]

The contemporary critique of orthodox economic theory[edit]

Logically incoherent theory[edit]

American economist John Weeks for example states that the neoclassical theories very often don't correspond with reality at all.[20] Weeks have stated that "Almost every generalization of neoclassical economics is logically false except under analytical constraints ("assumptions") so restrictive as to be absurd even in the abstract. [...] If a theory is logically flawed, empirical evidence for its predictions is no support.[20]

Normative assumptions[edit]

The economic-historian Daniel Ankarloo has claimed that the "simplifications", of modern economy isn't "simplifications" but pure falsehood regarding human behavior.[46] Ankarloo has also written about how the definition the economists have regarding "the market", is both logically incoherent with how the resource allocation in society really functions, and fundamentally ahistorical.[47] He cites how a winner of The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel by the name of Oliver Williamson expressed it "Economics doesn't explain the market, it assumes its eternal existence".[47]

Failure to revise theory[edit]

Ankarloo claims that the sciences has as a foundational principle to at first engage in observation of reality, and then as well as possible explain why reality is as it is. However, he finds that the relationship within economy is exactly the opposite. He finds that economics has conceptual apparatus without referent.[48]The conceptual apparatus first posits reality as it de facto is not with terminology like "equilibrium price", "perfect information", "optimal decisions".[49][50][51] Since reality according to Ankarloo is not structured with e.g. people with perfect information. Economists then have to explain why this is not the case even though the theories presuppose it. Here terminology like "market imperfections" and "Shock" is used.[52][53][54]

| This is the sandbox page for User:Pauloroboto (diff). |

- ^ a b Henderson, Willie (2000). John Ruskin's political economy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-15946-2. OCLC 48139638.

[...]Ruskin attempted a methodological/scientific critique of political economy. He fixed on ideas of 'natural laws', 'economic man' and the prevailing notion of 'value' to point out gaps and inconsistencies in the system of classical economics.

- ^ a b Ruskin, John. Unto this Last. pp. 128–129.

Observe, I neither impugn nor doubt the conclusions of the science if its terms are accepted. I am simply uninterested in them, as I should be in those of a science of gymnastics that assumed that men had no skeletons. It might be shown, on that supposition, that it would be advantageous to roll the students up into pellets, flatten them into cakes, or stretch them into cables; and that when these results were effected, the re-insertion of the skeleton would be attended with various inconveniences to their constitution. The reasoning might be admirable, the conclusions true, and the science deficient only inapplicability. Modern political economy stands on a precisely similar basis. Assuming, not that the human being has no skeleton, but that it is all skeleton, it founds an ossifiant theory of progress on this negation of a soul; and having shown the utmost that may be made of bones, and constructed a number of interesting geometrical figures with death's-heads and humeri, successfully proves the inconvenience of the reappearance of a soul among these corpuscular structures. I do not deny the truth of this theory: I simply deny its applicability to the present phase of the world.

- ^ a b Murray, Patrick (March 2020). "The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms". Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1086/708005. ISSN 2326-4462. S2CID 219746578.

"Bourgeois or capitalist production . . . is consequently for [Ricardo]," Marx writes, "not a specific definite mode of production, but simply the mode of production." [...] The illusion of the economic arises within what Marx calls the "bourgeois horizon," which trades in phenomenologically false bifurcations such as the purely subjective versus the purely objective, form versus content, forces versus relatisusons of production, the labor process versus the valorization process, distribution versus production, and more.

- ^ a b c Louis, Althusser; Balibar, Etienne (1979). Reading Capital. Verso Editions. p. 158. OCLC 216233458.

[...] 'to criticize' Political Economy cannot mean to criticize or correct certain inaccuracies or points of detail in an existing discipline nor even to fill in its gaps, its blanks, pursuing further an already largely initiated movement of exploration. 'To criticize Political Economy' means to confront it with a new problematic and a new object: i.e., to question the very object of Political Economy. But since Political Economy is defined as Political Economy by its object, the critique directed at it from the new object with which it is confronted could strike Political Economy's vital spot. This is indeed the case: Marx's critique of Political Economy cannot challenge the latter's object without disputing Political Economy itself, in its theoretical pretensions to autonomy and in the 'divisions' it creates in social reality in order to make itself the theory of the latter. [...] it queries not only the object of Political Economy, but also Political Economy itself as an object. [...] Political Economy, as it is defined by its pretensions, has no right to exist as far as Marx is concerned: if Political Economy thus conceived cannot exist, it is for de jure, not de facto reasons.

- ^ Fareld, Victoria; Kuch, Hannes (2020), From Marx to Hegel and Back, Bloomsbury Academic, p. 142,182, doi:10.5040/9781350082700.ch-001, ISBN 978-1-3500-8267-0, S2CID 213805975, retrieved 17 September 2021

- ^ Postone 1993, pp. 44, 192–216.

- ^ Mortensen. "Ekonomi". Tidskrift för litteraturvetenskap. 3:4: 9.

- ^ Postone, Moishe (1995). Time, labor, and social domination : a reinterpretation of Marx's critical theory. pp. 130, 5. ISBN 0-521-56540-5. OCLC 910250140.

- ^ Jönsson, Dan. "John Ruskin: En brittisk 1800-talsaristokrat för vår tid? - OBS". sverigesradio.se (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

Den klassiska nationalekonomin, som den utarbetats av John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith och David Ricardo, betraktade han som en sorts kollektivt hjärnsläpp ... [Transl. Ruskin viewed the classical political economy as it was developed by Mill, Smith, and Ricardo, as a kind of "collective mental lapse.]

- ^ Ramsay, Anders (21 December 2009). "Marx? Which Marx? Marx's work and its history of reception". www.eurozine.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

When it is based on the naturalistic understanding, the entire theoretical edifice of the critique of political economy breaks down. What is left is a theory not entirely unlike Adam Smith's, one in which individual labour creates value, and the capacity to create value becomes an ontological determination of labour. With good reason, one could speak of a Smithian Marxism ...

- ^ Ruccio, David (10 December 2020). "Toward a critique of political economy | MR Online". mronline.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

Marx arrives at conclusions and formulates new terms that run directly counter to those of Smith, Ricardo, and the other classical political economists.

- ^ Peperell, Nicole. "Beyond reification: Reclaiming Marx's Concept of the Fetish Character of the Commodity" (PDF). Kontradikce: A Journal for Critical Thought.

The critical edge of Marx's analysis does not derive, therefore, from any sort of declaration that this impersonal social relation does not exist, or is not 'truly' impersonal. Instead, it derives from the demonstration of how such a peculiar and counter-intuitive sort of social relation – one that possesses qualitative characteristics more normally associated with our interactions with non-social reality – comes to be unintentionally generated in collective practice.

- ^ Patterson, Orlando; Fosse, Ethan. "Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015.

[...] the real-world implementation of mainstream economic ideas has been a string of massive failures. Economic thinking undergirded the "deregulation" mantra leading up to the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and has fared no better in attempts to "fix" the ongoing crisis in Europe. [...] nowhere is the discipline's failure more apparent than in the area of development economics. In fact, the only countries that have effectively transformed from the "Third" to the "First World" since World War II violated the main principles of current and previous economic orthodoxies: [...] Only recently have economists come to accept the primacy of institutions in explaining and promoting economic growth, a position long held by sociologists [...]

(OpEd) - ^ Badeen, Dennis; Murray, Patrick. "A Marxian Critique of Neoclassical Economics' Reliance on Shadows of Capital's Constitutive Social Forms" (PDF). crisiscritique.org.

- ^ "The Poverty of Philosophy - Chapter 2.1". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Ruda, Frank; Hamza, Agon (2016). "Introduction: Critique of Political Economy" (PDF). Crisis and Critique. 3 (3): 5–7.

- ^ a b "Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Fisher, Mark (2018). K-punk : the collected and unpublished writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016). Darren Ambrose, Simon Reynolds. London, UK. ISBN 978-1-912248-28-5. OCLC 1023859141.

From the start, "economy" was the object-cause of a bourgeois "science", which hyperstitionally bootstrapped itself into existence, and then bent and melted the matter of this and every other world to fit its presuppositions — the greatest theocratic achievement in a history that was never human, an immense conjuring trick which works all the better because it came shrouded in that damp grey English and Scottish empiricism which claimed to have seen off all gods.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/14489/8%20Hamza%20Capital.pdf?sequence=4

- ^ a b c d e Weeks, John (2011). The irreconcilable inconsistencies of neoclassical macroeconomics : a false paradigm. New York: Routledge. pp. 1, 276. ISBN 978-0-415-68022-6. OCLC 753468528.

Almost every generalization of neoclassical economics is logically false except under analytical constraints ("assumptions") so restrictive as to be absurd even in the abstract. [...] If a theory is logically flawed, empirical evidence for its predictions is no support. Such evidence would imply that the theory may occasionally yield the appropriate prediction, but has the wrong explanation. The pre- Copernicus geocentric celestial theory yielded roughly accurate predictions of major astronomical events, but it was wrong; the sun does not circle the earth.

- ^ a b Murray, Patrick (2020-03). "The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms". Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1086/708005. ISSN 2326-4462.

"Bourgeois or capitalist production . . . is consequently for [Ricardo]," Marx writes, "not a specific definite mode of production, but simply the mode of production." [...] The illusion of the economic arises within what Marx calls the "bourgeois horizon," which trades in phenomenologically false bifurcations such as the purely subjective versus the purely objective, form versus content, forces versus relatisusons of production, the labor process versus the valorization process, distribution versus production, and more.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Poverty of Philosophy - Chapter 2.1". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Varoufakis, Yanis (2014). Economic indeterminacy : a personal encounter with the economists' peculiar nemesis. London. ISBN 978-0-415-66849-1. OCLC 829097248.

[on the subject of economists] a profession which operates like a priesthood, dedicated solely to the preservation of its dogmas"

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Becker (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. University of Chicago Press.

The combined assumptions of maximizing behavior, market equilibrium, and stable preferences, used relentlessly and unflinchingly, form the heart of the economic approach.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 69 (help) - ^ Blaug, Mark (2002), Mäki, Uskali (ed.), "Ugly currents in modern economics", Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, ISBN 978-0-521-81117-0, retrieved 24 March 2022Quote: ("economists have been unduly narrow in testing the falsifiable implications of theories in the sense that this is invariably taken to mean some statistical or econometric test. But history is just as much a test of patterns and trends in economic events as is regression analysis.")

- ^ Engels, Friedrich. "Deutsch-Franzosische Jahrbucher". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

According to the economists, the production costs of a commodity consist of three elements: the rent for the piece of land required to produce the raw material; the capital with its profit, and the wages for the labour required for production and manufacture. But it becomes immediately evident that capital and labour are identical, since the economists themselves confess that capital is "stored-up labour." We are therefore left with only two sides – the natural, objective side, land; and the human, subjective side, labour, which includes capital and, besides capital, a third factor which the economist does not think about – I mean the mental element of invention, of thought, alongside the physical element of sheer labour. What has the economist to do with inventiveness? Have not all inventions fallen into his lap without any effort on his part? Has one of them cost him anything? Why then should he bother about them in the calculation of production costs? Land, capital and labour are for him the conditions of wealth, and he requires nothing else. Science is no concern of his.

{{cite web}}: Check|author-link=value (help) - ^ a b c Blaug, Mark (2002), Mäki, Uskali (ed.), "Ugly currents in modern economics", Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, ISBN 978-0-521-81117-0, retrieved 24 March 2022Quote:

"Mindful of the poor empirical track record of rational expectations, Real Business Cycle theorists, such as Edward Prescott and Finn Kydland (1982), have adopted a new method for confirming their theories. Instead of providing models that are capable of being tested by standard econometric methods, they subject them to “calibration,” that is, they quantify the parameters of a model on the basis of casual empiricism or a variety of unrelated econometric studies so chosen as to guarantee that the model mimics some particular feature of the historical data. The claim of Real Business Cycle theorists is that their models do indeed track the important time series fairly closely and even depict widely accepted “stylized facts” about the business cycle."

- ^ a b c Aje., Johnsdotter, Sara. Carlbom,; Ankarloo (2015). Goda sanningar : debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6. OCLC 943322546.

English translation: "I base my standpoint on the observation that if it is the sciences task to first observe reality as it is, and then as well as possible explain why this is the case, then modern economics is no scientific practice. Because economics is through its whole conceptual apparatus unique in doing exactly the opposite. The economists first define the world as it is not - with words as "perfect", "optimal" and "complete". Then they try, as well as they can, to explain why it is not. - With words like "skewed", and "imperfect. As a parable about the subject I have encountered expresses it "the economist views a horse like an imperfect unicorn." "Original: Jag grundar min uppfattning i sak på observationen att om det är vetenskapens grundförutsättning att först utgå från världen så som den är och sedan så gott det går försöka förklara varför den är så, då är den moderna nationalekonomin ingen vetenskaplig praktik. Ty nationalekonomin är genom hela sin begreppsapparat unik i att göra precis tvärtom. Nationalekonomerna definierar först världen som den inte är - med ord som "perfekt", "optimal" och "fullständig". Sedan försöker de så gott de kan förklara varför den inte är så - med ord som "snedvriden" och "imperfekt". Som en liknelse om saken jag stött på uttrycker det "nationalekonomen betraktar en häst som en ofullkomlig enhörning".

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 665 (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mäki, Uskali (2002). Fact and Fiction in Economics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51.

[...]we should [not] always discard hypotheses that have not yet yielded empirically falsifiable implications but simply that theories such as general equilibrium theory, which are untestable even in principle, should be regarded with deep suspicion.

- ^ Perelman, Michael (1996). The end of economics. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13737-3. OCLC 33359588.

[...]I intend to expose economics as a pseudo-science that stands in the way of human betterment in the hope that we can develop new practices and better institutions that will allow us to manage our lives in a more satisfactory manner.

- ^ "Deutsch-Franzosische Jahrbucher". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

Political economy came into being as a natural result of the expansion of trade, and with its appearance elementary, unscientific huckstering was replaced by a developed system of licensed fraud, an entire science of enrichment.

- ^ a b Knowles, Rob (2004). Political economy from below : economic thought in communitarian anarchism, 1840-1914. New York. ISBN 978-1-135-40892-3. OCLC 862746058.

The anarchist Kropotkin referred to political economy as 'that pseudo-science of the bourgeoisie,' and in words which sympathetically resonated with those of Thorold Rogers, he noted that: So far academic political economy has been only an enumeration of what happens under [certain] conditions—without distinctly stating the conditions themselves. And then, having described the facts which arise in our society under these conditions, they represent to us these facts as rigid, inevitable economic laws.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 189 (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow, Doubleday Canada.

- ^ Steve., Keen, (2011). Debunking economics : the naked emperor dethroned?. Zed Book. pp. X. ISBN 978-1-84813-993-0. OCLC 840838902.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fronesis #16 pp.62 (Marx betonar också betydelsen av vår tro på papperspengar och krediter, vilken måste ha en kvasireligiös karaktär för att [...] en [...] ekonomi ska kunna upprätthållas.)

- ^ •Steve, Keen, (2011), Debunking economics : the naked emperor dethroned?, pp. X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Blaug, Mark (2002), Mäki, Uskali (ed.), "Ugly currents in modern economics", Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, Mark; Mäki, Uskali (2002), Ugly currents in modern economics, Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, ISBN 978-0-521-81117-0{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) •Fronesis, vol. 16, p. 62 •Weeks, John (2011), The irreconcilable inconsistencies of neoclassical macroeconomics : a false paradigm., vol. New York: Routledge. pp. 1, 276. ISBN 978-0-415-68022-6. OCLC 753468528, New York: Routledge, pp. 1, 276, ISBN 9780415680226 - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:32was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Is Economics Unscientific | Articles & Shortlisted Essays | SPE". spe.org.uk. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ •Henderson,, Willie (2000), John Ruskin's political economy., London: Routledge.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)•Ankarloo (2015), Goda sanningar?, ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6 •Knowles, Rob (2004), Political economy from below : economic thought in communitarian anarchism, 1840-1914., ISBN 978-1-135-40892-3•Bonefeld, Werner (2014), Critical theory and the critique of political economy : on subversion and negative reason., ISBN 978-1-4411-5227-5 •Fisher, Mark (2018), K-punk : the collected and unpublished writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016), London, ISBN 978-1-912248-28-5{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)•Perelman, Michael (1996), The end of economics, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13737-3 Murray, Patrick (2020), The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms, vol. Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27., doi:10.1086/708005, ISSN 2326-4462 •Patterson, Orlando, Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics, The New York Times - ^ Bonefeld, Werner (2014). Critical theory and the critique of political economy : on subversion and negative reason. New York. ISBN 978-1-4411-5227-5. OCLC 876607305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ •Henderson,, Willie (2000), John Ruskin's political economy., London: Routledge.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) •Ankarloo (2015), Goda sanningar?, ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6 •Knowles, Rob (2004), Political economy from below : economic thought in communitarian anarchism, 1840-1914., ISBN 978-1-135-40892-3 •Patterson, Orlando, Overreliance on the Pseudo-Science of Economics, The New York Times •Perelman, Michael (1996), The end of economics, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13737-3 •Bonefeld, Werner (2014), Critical theory and the critique of political economy : on subversion and negative reason., ISBN 978-1-4411-5227-5 •Murray, Patrick (2020), The Illusion of the Economic: Social Theory without Social Forms, vol. Critical Historical Studies. 7 (1): 19–27., doi:10.1086/708005, ISSN 2326-4462 •Fisher, Mark (2018), K-punk : the collected and unpublished writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016), London, ISBN 978-1-912248-28-5{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Robert Shiller: is economics a science?". the Guardian. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Ozimek, Adam. "Enough Already With The Sweeping Claims That Economics Is Unscientific". Forbes. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ •Steve, Keen, (2011), Debunking economics : the naked emperor dethroned?, pp. X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) •Blaug, Mark (2002), Mäki, Uskali (ed.), "Ugly currents in modern economics", Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, Mark; Mäki, Uskali (2002), Ugly currents in modern economics, Fact and Fiction in Economics: Models, Realism and Social Construction, Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–56, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511493317.003, ISBN 978-0-521-81117-0{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) •Fronesis, vol. 16, p. 62 •Weeks, John (2011), The irreconcilable inconsistencies of neoclassical macroeconomics : a false paradigm., vol. New York: Routledge. pp. 1, 276. ISBN 978-0-415-68022-6. OCLC 753468528, New York: Routledge, pp. 1, 276, ISBN 9780415680226 - ^ Hayek, Friedrich A. von (2008). A free-market monetary system. Auburn, AL: Ludwig Von Mises Institute. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-933550-37-4. OCLC 502635266.

On the other hand, the economists are at this moment called upon to say how to extricate the free world from the serious threat of accelerating inflation which, it must be admitted, has been brought about by policies which the majority of economists recommended and even urged governments to pursue. We have indeed at the moment little cause for pride: as a profession we have made a mess of things. It seems to me that this failure of the economists to guide policy more successfully is closely connected with their propensity to imitate as closely as possible the procedures of the brilliantly successful physical sciences—an attempt which in our field may lead to outright error. It is an approach which has come to be described as the "scientistic" attitude—an attitude which, as I defined it some thirty years ago, is decidedly unscientific in the true sense of the word, since it involves a mechanical and uncritical application of habits of thought to fields different from those in which they have been formed.

- ^ Johnsdotter, Sara; Carlbom, Aje (2015). Goda sanningar : debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Nordic Academic Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6. OCLC 943322546.

- ^ a b Johnsdotter, Sara; Carlbom, Aje (2015). Goda sanningar : debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Nordic Academic Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6. OCLC 943322546.

- ^ Johnsdotter, Sara; Carlbom, Aje (2015). Goda sanningar : debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Nordic Academic Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6. OCLC 943322546.

- ^ Eklund, Klas (2017). Vår ekonomi : en introduktion till samhällsekonomin. Studentlitteratur. pp. 56–61, 64, 93, 98, 140, 158–59, 162–105. ISBN 978-91-44-11772-0. OCLC 1028037336.

- ^ Aje., Johnsdotter, Sara. Carlbom, (2015). Goda sanningar : debattklimatet och den kritiska forskningens villkor. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-87351-84-6. OCLC 943322546.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ What is neoclassical economics? : debating the origins, meaning and significance. Jamie Morgan. London. 2016. ISBN 978-1-317-33451-4. OCLC 930083125.

The conceptions developed by the latter set of interpreters do have significant features in common. Perhaps the most notable is the highly abstract nature of the characterisations advanced, very often taking the form of a set of 'axioms' or 'meta-axioms' or perhaps a 'meta-theory'. Additional commonalities are that the axioms identified tend to make reference to individuals as the units of analysis and indicate something of the states of knowledge and/or forms of typical behaviour of these individuals. In addition it is often the case that certain supposed (typically equilibrium) states of the economic system get a mention.