User:Patrick Welsh/postmodernism draft

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourse[1][2] characterized by skepticism towards elements of the Enlightenment worldview. It questions the "grand narratives" of modernity, rejects the certainty of knowledge and stable meaning, and acknowledges the influence of ideology in maintaining political power.[3][4] Objective claims are dismissed as naïve realism,[5] emphasizing the conditional nature of knowledge.[4] Postmodernism embraces self-referentiality, epistemological relativism, moral relativism, pluralism, irony, irreverence, and eclecticism.[4] It opposes the "universal validity" of binary oppositions, stable identity, hierarchy, and categorization.[6][7]

Emerging in the mid-twentieth century as a reaction against modernism,[8][9][10] postmodernism has permeated various disciplines[11] and is linked to critical theory, deconstruction, and post-structuralism.[4]

Critics argue that postmodernism promotes obscurantism, abandons Enlightenment rationalism and scientific rigor, and contributes little to analytical or empirical knowledge.[12]

The problem of definition[edit]

| Postmodernism |

|---|

| Preceded by Modernism |

| Postmodernity |

| Fields |

| Reactions |

| Related |

"Postmodernism" is "a highly contested term"[13], referring to "a particularly unstable concept",[14] that "names many different kinds of cultural objects and phenomena in many different ways".[15] Critics have described it as "an exasperating term"[16] and claim that its "indefinably" is "a truism".[17] Put otherwise, postmodernism is "several things at once".[16] It has no single definition, and the term does not name any single unified phenomenon, but rather many diverse phenomena: "postmodernisms rather than one postmodernism".[18][19]

The term first appeared in print in 1870,[20][21] but it only came into general circulation with its current range of significations in the 1950s—60s.[22][13][23] Discussion was most articulate in areas with a large body of critical discourse around the modernist movement; in particular, architecture, the visual arts, and literature. Even here, however, there continues to be disagreement about such basic issues as whether postmodernism is a break with modernism, a renewal and intensification of modernism,[15] or even, both at once, a rejection and a radicalization of its historical predecessor.[24]

"Postmodernism" was only introduced to the philosophical lexicon by Jean-François Lyotard in his 1979[a] The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge.[25][13] Its conceptual origins, however, trace back to Friedrich Nietzsche in the late 19th century and Martin Heidegger in the early 20th, among others.[26]

Usages[edit]

Early appearances[edit]

The term "postmodern" was first used in 1870 by the artist John Watkins Chapman, who described "a Postmodern style of painting" as a departure from French Impressionism.[20][27] Similarly, the first citation given by the Oxford English Dictionary is dated to 1916, describing Gus Mager as "one of the few 'post' modern painters whose style is convincing".[28]

Episcopal priest and cultural commentator J. M. Thompson, in an 1914 article, uses the term to describe changes in attitudes and beliefs in the critique of religion, writing, "the raison d'être of Post-Modernism is to escape from the double-mindedness of modernism by being thorough in its criticism by extending it to religion as well as theology, to Catholic feeling as well as to Catholic tradition.[29] In 1926, Bernard Iddings Bell, president of St. Stephen's College (now Bard College) and also an Episcopal priest, published Postmodernism and Other Essays, which marks the first use of the term to describe an historical period following modernity.[30][31] The essay criticizes lingering socio-cultural norms, attitudes, and practices of the Enlightenment. It is also critical of a purported cultural shift away from traditional Christian beliefs.[32][33][34]

The term "postmodernity" was first used in an academic historical context as a general concept for a movement by Arnold J. Toynbee in an 1939 essay, which states that "Our own Post-Modern Age has been inaugurated by the general war of 1914–1918".[35]

In 1942, the literary critic and author H. R. Hays describes postmodernism as a new literary form.[36] Also in the arts, the term was first used in 1949 to describe a dissatisfaction with the modernist architectural movement known as the International Style.[37]

In art criticism[edit]

In social theory[edit]

In 1979, it was introduced as a philosophical term by Jean-François Lyotard in The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge.[25][13]

Definition[edit]

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourse[1][2] which challenges worldviews associated with Enlightenment rationality dating back to the 17th century.[4] Postmodernism is associated with relativism and a focus on the role of ideology in the maintenance of economic and political power.[4] Postmodernists are "skeptical of explanations which claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the relative truths of each person".[38] It considers "reality" to be a mental construct.[38] Postmodernism rejects the possibility of unmediated reality or objectively-rational knowledge, asserting that all interpretations are contingent on the perspective from which they are made;[5] claims to objective fact are dismissed as naive realism.[4]

Postmodern thinkers frequently describe knowledge claims and value systems as contingent or socially-conditioned, describing them as products of political, historical, or cultural discourses[39] and hierarchies.[4] Accordingly, postmodern thought is broadly characterized by tendencies to self-referentiality, epistemological and moral relativism, pluralism, and irreverence.[4] Postmodernism is often associated with schools of thought such as deconstruction and post-structuralism.[4] Postmodernism relies on critical theory, which considers the effects of ideology, society, and history on culture.[40] Postmodernism and critical theory commonly criticize universalist ideas of objective reality, morality, truth, human nature, reason, language, and social progress.[4]

Initially, postmodernism was a mode of discourse on literature and literary criticism, commenting on the nature of literary text, meaning, author and reader, writing, and reading.[41] Postmodernism developed in the mid- to late-twentieth century across many scholarly disciplines as a departure or rejection of modernism.[42][9][10] As a critical practice, postmodernism employs concepts such as hyperreality, simulacrum, trace, and difference, and rejects abstract principles in favor of direct experience. [citation needed]

Manifestations[edit]

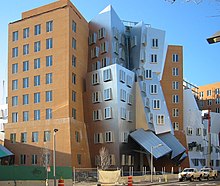

Architecture[edit]

Modern Architecture, as established and developed by Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, was focused on:

- the attempted harmony of form and function;[43] and,

- the dismissal of "frivolous ornament."[44][45][page needed]

- the pursuit of a perceived ideal perfection;

They argued for architecture that represented the spirit of the age as depicted in cutting-edge technology, be it airplanes, cars, ocean liners, or even supposedly artless grain silos.[46] Modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is associated with the phrase "less is more".

Critics of Modernism have:

- argued that the attributes of perfection and minimalism are themselves subjective;

- pointed out anachronisms in modern thought; and,

- questioned the benefits of its philosophy.[47][full citation needed]

The intellectual scholarship regarding postmodernism and architecture is closely linked with the writings of critic-turned-architect Charles Jencks, beginning with lectures in the early 1970s and his essay "The Rise of Post Modern Architecture" from 1975.[48] His magnum opus, however, is the book The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, first published in 1977, and since running to seven editions.[49] Jencks makes the point that Post-Modernism (like Modernism) varies for each field of art, and that for architecture it is not just a reaction to Modernism but what he terms double coding: "Double Coding: the combination of Modern techniques with something else (usually traditional building) in order for architecture to communicate with the public and a concerned minority, usually other architects."[50] In their book, "Revisiting Postmodernism", Terry Farrell and Adam Furman argue that postmodernism brought a more joyous and sensual experience to the culture, particularly in architecture.[51]

Graphic design[edit]

Early mention of postmodernism as an element of graphic design appeared in the British magazine, "Design".[52] A characteristic of postmodern graphic design is that "retro, techno, punk, grunge, beach, parody, and pastiche were all conspicuous trends. Each had its own sites and venues, detractors and advocates."[53]

Literature[edit]

Jorge Luis Borges' (1939) short story "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote", is often considered as predicting postmodernism[54] and is a paragon of the ultimate parody.[55] Samuel Beckett is also considered an important precursor and influence. Novelists who are commonly connected with postmodern literature include Vladimir Nabokov, William Gaddis, Umberto Eco, Italo Calvino, Pier Vittorio Tondelli, John Hawkes, William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, John Barth, Robert Coover, Jean Rhys, Donald Barthelme, E. L. Doctorow, Richard Kalich, Jerzy Kosiński, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon[56] (Pynchon's work has also been described as high modern[57]), Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Ana Lydia Vega, Jáchym Topol and Paul Auster.

In 1971, the American scholar Ihab Hassan published The Dismemberment of Orpheus: Toward a Postmodern Literature, an early work of literary criticism from a postmodern perspective that traces the development of what he calls "literature of silence" through Marquis de Sade, Franz Kafka, Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett, and many others, including developments such as the Theatre of the Absurd and the nouveau roman.

In Postmodernist Fiction (1987), Brian McHale details the shift from modernism to postmodernism, arguing that the former is characterized by an epistemological dominant and that postmodern works have developed out of modernism and are primarily concerned with questions of ontology.[58] McHale's second book, Constructing Postmodernism (1992), provides readings of postmodern fiction and some contemporary writers who go under the label of cyberpunk. McHale's "What Was Postmodernism?" (2007)[59] follows Raymond Federman's lead in now using the past tense when discussing postmodernism.

Music[edit]

Jonathan Kramer has written that avant-garde musical compositions (which some would consider modernist rather than postmodernist) "defy more than seduce the listener, and they extend by potentially unsettling means the very idea of what music is."[60] In the 1960s, composers such as Terry Riley, Henryk Górecki, Bradley Joseph, John Adams, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Michael Nyman, and Lou Harrison reacted to the perceived elitism and dissonant sound of atonal academic modernism by producing music with simple textures and relatively consonant harmonies, whilst others, most notably John Cage challenged the prevailing narratives of beauty and objectivity common to Modernism.

Author on postmodernism, Dominic Strinati, has noted, it is also important "to include in this category the so-called 'art rock' musical innovations and mixing of styles associated with groups like Talking Heads, and performers like Laurie Anderson, together with the self-conscious 'reinvention of disco' by the Pet Shop Boys".[61]

In the late-20th century, avant-garde academics labelled American singer Madonna, as the "personification of the postmodern",[62] with Christian writer Graham Cray saying that "Madonna is perhaps the most visible example of what is called post-modernism",[63] and Martin Amis described her as "perhaps the most postmodern personage on the planet".[63] She was also suggested by literary critic Olivier Sécardin to epitomise postmodernism.[64]

Philosophy[edit]

In the 1970s, a disparate group of post-structuralists in France developed a critique of modern philosophy with roots discernible in Friedrich Nietzsche, Søren Kierkegaard, and Martin Heidegger.[65] Although few themselves relied upon the term, they became known to many as postmodern theorists.[66] Notable figures include Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, and others. By the 1980s, this spread to America in the work of Richard Rorty and others.[65]

Structuralism and post-structuralism[edit]

Structuralism is a philosophical movement that was developed by French academics in the 1950s, partly in response to French existentialism, and often interpreted in relation to modernism and high modernism. Thinkers include anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, semiotician Algirdas Greimas, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, and literary theorist Roland Barthes.[67]

Like structuralists, post-structuralists start from the assumption that people's identities, values, and economic conditions determine each other rather than having intrinsic properties that can be understood in isolation.[68] Structuralists explore how the subjects of their study might be described as a set of essential relationships, schematics, or mathematical symbols. Post-structuralism, by contrast, is characterized by new ways of thinking through structuralism, contrary to the original form.[69]

Deconstruction[edit]

One of the most well-known postmodernist concerns is deconstruction, a theory for philosophy, literary criticism, and textual analysis developed by Jacques Derrida.[70] Derrida's work has been seen as rooted in a statement found in Of Grammatology: "Il n'y a pas de hors-texte" ("there is nothing outside the text"). This statement is part of a critique of "inside" and "outside" metaphors when referring to the text, and is a corollary to the observation that there is no "inside" of a text as well.[71] This attention to a text's unacknowledged reliance on metaphors and figures embedded within its discourse is characteristic of Derrida's approach. Derrida's method sometimes involves demonstrating that a given philosophical discourse depends on binary oppositions or excluding terms that the discourse itself has declared to be irrelevant or inapplicable. Derrida's philosophy inspired a postmodern movement called deconstructivism among architects, characterized by a design that rejects structural "centers" and encourages decentralized play among its elements. Derrida discontinued his involvement with the movement after the publication of his collaborative project with architect Peter Eisenman in Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman.[72]

The Postmodern Condition[edit]

Jean-François Lyotard is credited with being the first to use the term "postmodern" in a philosophical context, in his 1979 work The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. In it, he follows Wittgenstein's language games model and speech act theory, contrasting two different language games, that of the expert, and that of the philosopher. He talks about the transformation of knowledge into information in the computer age and likens the transmission or reception of coded messages (information) to a position within a language game.[3]

Lyotard defined philosophical postmodernism in The Postmodern Condition, writing: "Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity towards metanarratives...." [73] where what he means by metanarrative (in French, grands récits) is something like a unified, complete, universal, and epistemically certain story about everything that is. Against totalizing metanarratives, Lyotard and other postmodern philosophers argue that truth is always dependent upon historical and social context rather than being absolute and universal—and that truth is always partial and "at issue" rather than being complete and certain.[73]

Urban planning[edit]

Modernism sought to design and plan cities that followed the logic of the new model of industrial mass production; reverting to large-scale solutions, aesthetic standardisation, and prefabricated design solutions.[74] Modernism eroded urban living by its failure to recognise differences and aim towards homogeneous landscapes (Simonsen 1990, 57). Jane Jacobs' 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities[75] was a sustained critique of urban planning as it had developed within modernism and marked a transition from modernity to postmodernity in thinking about urban planning.[76]

The transition from modernism to postmodernism is often said to have happened at 3:32 pm on 15 July in 1972, when Pruitt–Igoe, a housing development for low-income people in St. Louis designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki, which had been a prize-winning version of Le Corbusier's 'machine for modern living,' was deemed uninhabitable and was torn down.[77] Since then, postmodernism has involved theories that embrace and aim to create diversity. It exalts uncertainty, flexibility and change and rejects utopianism while embracing a utopian way of thinking and acting.[78] Postmodernity of 'resistance' seeks to deconstruct modernism and is a critique of the origins without necessarily returning to them.[79] As a result of postmodernism, planners are much less inclined to lay a firm or steady claim to there being one single 'right way' of engaging in urban planning and are more open to different styles and ideas of 'how to plan'.[80]

The postmodern approach to understanding the city were pioneered in the 1980s by what could be called the "Los Angeles School of Urbanism" centered on the UCLA's Urban Planning Department in the 1980s, where contemporary Los Angeles was taken to be the postmodern city par excellence, contra posed to what had been the dominant ideas of the Chicago School formed in the 1920s at the University of Chicago, with its framework of urban ecology and emphasis on functional areas of use within a city, and the concentric circles to understand the sorting of different population groups.[81] Edward Soja of the Los Angeles School combined Marxist and postmodern perspectives and focused on the economic and social changes (globalization, specialization, industrialization/deindustrialization, neo-liberalism, mass migration) that lead to the creation of large city-regions with their patchwork of population groups and economic uses.[81][82]

Works cited[edit]

Aylesworth, Gary. "Postmodernism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- Baugh, Bruce (2003). French Hegel: From Surrealism to Postmodernism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415965866.

- Bell, Bernard Iddings (1926). Postmodernism and Other Essays. Milwaukie: Morehouse Publishing Company.

- Bertens, Johannes Willem (1995). The Idea of the Postmodern: A History. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415060110.

- Bertens, Johannes Willem (1997). International Postmodernism: Theory and Literary Practice. J. Benjamins. ISBN 978-1556196027.

- Bernstein, Richard J. (1992). The New Constellation: The Ethical-Political Horizons of Modernity / Postmodernity. Polity. ISBN 978-0745609201.

- Brooker, Peter (2003). A Glossary of Cultural Theory (2nd ed.). Arnold. ISBN 978-0340807002.

- Butler, Christopher (10 October 2002). Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0192802392.

- Buchanan, Ian (2018). A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198794790.

- Connor, Steven (15 July 2004). The Cambridge Companion to Postmodernism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521648400.

- Gutting, Gary (10 May 2001). French Philosophy in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521662123.

- Harvey, David (8 April 1992). The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Wiley. ISBN 978-0631162940.

- Hassan, Ihab (1987). The Postmodern Turn, Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture. Ohio University Press. p. 12ff.

- Madsen, Deborah (1995). Postmodernism: A Bibliography. Amsterdam; Atlanta, Georgia: Rodopi.

- Payne, Michael; Barbera, Jessica Rae (6 May 2013). A Dictionary of Cultural and Critical Theory. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118438817.

- Russello, Gerald J. (25 October 2007). The Postmodern Imagination of Russell Kirk. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826265944 – via Google Books.

- "postmodern (adjective & noun)". Oxford English Dictionary. 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- Sim, Stuart (2011). The Routledge Companion to Postmodernism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415583329.

- Thompson, J. M. (July 1914). "Post-Modernism". The Hibbert Journal. XII (4): 733.

- Toynbee, Arnold J. (1961) [1939]. A study of History. Vol. 5. Oxford University Press. p. 43 – via Google Books.

- Usher, Robin; Bryant, Ian (January 1997). Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge: Learning Beyond the Limits. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415120203.

- Vanhoozer, Kevin J. (2003). "Theology and the Condition of Postmodernity: A Report on Knowledge (of God)". In Vanhoozer, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Postmodern Theology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–25.

- Welsch, Wolfgang; Sandbothe, Mike (1997). "Postmodernity as a Philosophical Concept". International Postmodernism. Comparative History of Literatures in European Languages. Vol. XI. p. 76. doi:10.1075/chlel.xi.07wel. ISBN 978-90-272-3443-8 – via Google Books.

- Russell Kirk: American Conservative. University Press of Kentucky. 9 November 2015. ISBN 9780813166209 – via Google Books.

-

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) -

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) -

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) -

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help)

Notes[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ English translation, 1984.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Nuyen, A. T. (1992). "The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 25 (2). Penn State University Press: 183–194. JSTOR 40237717.

- ^ a b Torfing, Jacob (1999). New theories of discourse : Laclau, Mouffe, and Z̆iz̆ek. Oxford, UK Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19557-2.

- ^ a b Aylesworth, Gary (5 February 2015) [1st pub. 2005]. "Postmodernism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. sep-postmodernism (Spring 2015 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Duignan, Brian. "Postmodernism". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b Bryant, Ian; Johnston, Rennie; Usher, Robin (2004). Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge: Learning Beyond the Limits. Routledge. p. 203.

- ^ "postmodernism". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2019 – via AHDictionary.com.

Of or relating to an intellectual stance often marked by eclecticism and irony and tending to reject the universal validity of such principles as hierarchy, binary opposition, categorization, and stable identity.

- ^ Bauman, Zygmunt (1992). Intimations of postmodernity. London New York: Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-415-06750-8.

- ^ Lyotard 1989; Mura 2012, pp. 68–87

- ^ a b "postmodernism". Oxford Dictionary (American English). Archived from the original on 17 January 2013 – via oxforddictionaries.com.

- ^ a b "postmodern". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). 2000. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008 – via Bartleby.com.

- ^ Hutcheon 2002.

- ^ Hicks 2011; Brown 2013; Bruner 1994, pp. 397–415; Callinicos 1989; Devigne 1994; Sokal & Bricmont 1999

- ^ a b c d Buchanan 2018.

- ^ Bertens 1995, p. 11.

- ^ a b Payne & Barbera 2010, p. 567.

- ^ a b Bertens 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Aylesworth 2015, Introduction.

- ^ Brooker 2003, p. 204.

- ^ Vanhoozer 2003, p. 3.

- ^ a b Welsch & Sandbothe 1997, p. 76.

- ^ Hassan 1987, pp. 12ff.

- ^ Brooker 2003, p. 202.

- ^ Bertens 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Bertens 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Aylesworth 2015, Introduction & §2.

- ^ Aylesworth 2015, location=§1 Precursors.

- ^ Hassan 1987, pp. 12ff..

- ^ "postmodern (adjective & noun)". Oxford English Dictionary. 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Thompson 1914, p. 733.

- ^ Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. 2004.

- ^ Madsen 1995.

- ^ Bell 1926.

- ^ Russell Kirk: American Conservative. University Press of Kentucky. 9 November 2015. ISBN 9780813166209 – via Google Books.

- ^ Russello 2007.

- ^ Toynbee 1961, p. 43.

- ^ "postmodernism (n.)". OED. 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004

- ^ a b "Postmodernism Glossary". Faith and Reason. 11 September 1998. Retrieved 10 June 2019 – via PBS.

- ^ Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated from Hebrew by the author with John Purcell and Haim Watzman. London: Penguin Random House UK. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8. OCLC 910498369.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (1995). Media culture: cultural studies, identity, and politics between the modern and the postmodern. London / New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10569-2.

- ^ Lyotard 1989.

- ^ Mura 2012, pp. 68–87; Hutcheon 2002; Hatch 2013

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (March 1896). "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered". Lippincott's Magazine.

- ^ Loos, Adolf (1910). Ornament and Crime.

- ^ Tafuri, Manfredo (1976). Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (PDF). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-20033-2.

- ^ Le Corbusier (1985) [1921]. Towards a New Architecture. Dover Publications.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (2018-09-28). "Remembering Robert Venturi, the US architect who said: 'Less is a bore'". Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Jencks, Charles (1975). "The Rise of Post Modern Architecture". Architectural Association Quarterly. 7 (4): 3–14 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jencks, Charles (1977). The language of post-modern architecture. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0167-5.

- ^ Jencks, Charles (1974). The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. London: Academy Editions.

- ^ Farrell, Terry (2017). Revisiting Postmodernism. Newcastle upon Tyne: RIBA Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85946-632-2.

- ^ Poynor, Rick (2003). No more rules: graphic design and postmodernism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-300-10034-5.

- ^ Drucker, Johanna; McVarish, Emily (2008). Graphic Design History. Pearson. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-0-13-241075-5.

- ^ Bellalouna, Elizabeth; LaBlanc, Michael L.; Milne, Ira Mark (2000). Literature of Developing Nations for Students: L-Z. Gale. p. 50. ISBN 9780787649302 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stavans, Ilan (1997). Antiheroes: Mexico and Its Detective Novel. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8386-3644-2.

- ^ McHale, Brian (2011). "Pynchon's postmodernism". In Dalsgaard, Inger H.; Herman, Luc; McHale, Brian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Pynchon. pp. 97–111. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521769747.010. ISBN 978-0-521-76974-7.

- ^ "Mail, Events, Screenings, News: 32". People.bu.edu. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ McHale, B. (2003). Postmodernist Fiction. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 1134949162 – via Google Books.

- ^ McHale, Brian (20 December 2007). "What Was Postmodernism?". Electronic Book Review. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Kramer, Jonathan (2016). Postmodern music, postmodern listening. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-5013-0602-0.

- ^ Strinati, Dominic (1995). An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture. London: Routledge. p. 234.

- ^ Brown, Stephen (2003). "On Madonna'S Brand Ambition: Presentation Transcript". Association For Consumer Research. pp. 119–201. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ a b McGregor, Jock (2008). "Madonna: Icon of Postmodernity" (PDF). L'Abri. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ River, Canavan; McCamley, Claire (February 2020). "The passing of the postmodern in pop? Epochal consumption and marketing from Madonna, through Gaga, to Taylor". Journal of Business Research. 107: 222–230. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.005.

- ^ a b Best, Steven; Kellner, Douglas (2 November 2001). "The Postmodern Turn in Philosophy: Theoretical Provocations and Normative Deficits". UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. UCLA. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard J. (1992). The New Constellation: The Ethical-Political Horizons of Modernity / Postmodernity. Polity. p. 11. ISBN 978-0745609201.

- ^ Kurzweil, Edith (2017). The age of structuralism : from Lévi-Strauss to Foucault. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-30584-6.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1963). Structural Anthropology (I ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 324. ISBN 0-465-09516-X.

quoting D'Arcy Westworth Thompson states: "To those who question the possibility of defining the interrelations between entities whose nature is not completely understood, I shall reply with the following comment by a great naturalist: In a very large part of morphology, our essential task lies in the comparison of related forms rather than in the precise definition of each; and the deformation of a complicated figure may be a phenomenon easy of comprehension, though the figure itself has to be left unanalyzed and undefined."

- ^ Yilmaz, K. (2010). "Postmodernism and its Challenge to the Discipline of History: Implications for History Education". Educational Philosophy & Theory. 42 (7): 779–795. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00525.x. S2CID 145695056.

- ^ Culler, Jonathan (2008). On deconstruction: theory and criticism after structuralism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-46151-1.

- ^ Derrida, Jacques (8 January 1998). "The Exorbitant Question of Method" (PDF). Of Grammatology. Translated by Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (Corrected ed.). Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 158–59, 163. ISBN 0-8018-5830-5.

- ^ Peeters, Benoît (2013). Derrida: A Biography. Translated by Brown, Andrew. Polity Press. pp. 377–78. ISBN 978-0-7456-5615-1.

- ^ a b Lyotard, J.-F. (1979). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-944624-06-7. OCLC 232943026.

- ^ Goodchild 1990, pp. 119–137.

- ^ Jacobs, Jane (1993). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64433-4.

- ^ Irving 1993, p. 479.

- ^ Irving 1993, p. 480.

- ^ Hatuka & d'Hooghe 2007, pp. 20–27.

- ^ Irving 1993, p. 460.

- ^ Goodchild 1990, pp. 119–137; Hatuka & d'Hooghe 2007, pp. 20–27; Irving 1993, pp. 474–487; Simonsen 1990, pp. 51–62

- ^ a b Soja, Edward W. (14 March 2014). My Los Angeles: From Urban Restructuring to Regional Urbanization. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95763-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shiel, Mark (30 October 2017). "Edward Soja". Mediapolis. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Cut material[edit]

Postmodernism in architecture was initially marked by a re-emergence of surface ornament, reference to surrounding buildings in urban settings, historical reference in decorative forms (eclecticism), and non-orthogonal angles.[1] Most scholars today agree postmodernism began to compete with modernism in the late 1950s, and gained ascendancy over it in the 1960s.[2]

In 1942, the literary critic and author H. R. Hays describes postmodernism as a new literary form.[3]

- ^ Seah, Isaac, Post Modernism in Architecture

- ^ Huyssen, Andreas (1986). After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 188.

- ^ "postmodernism (n.)". OED. 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2024.