User:Old Moonraker/sandbox

"The wisdom of crowds cannot prevent the idiocy of individuals."—Wikipedia; the wisdom of Crowds, "The Guardian", 27 August 2009.

Apositive

Lazy editor's cheat[edit]

Substantial reason[edit]

"The Arbitration Committee has ruled that editors should not change an article from one guideline-defined style to another without a substantial reason unrelated to mere choice of style".

Userbox test[edit]

| This user is proud to be a Moonraker. |  |

Watling Street[edit]

52°39′22.5″N 1°55′37.7″W / 52.656250°N 1.927139°W

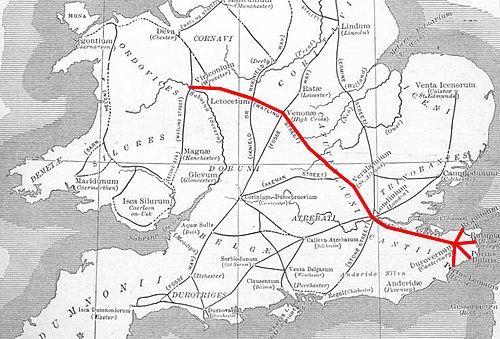

Watling Street is the name given to an ancient trackway in England and Wales that was first used by the Britons mainly between the modern cities of Canterbury and St Albans. The Romans later paved the road. Its route is now covered by the A2 road from Dover to London, and the A5 road from London to Wroxeter. The name derives from the Old English Wæcelinga Stræt. Originally the word "street" simply meant a paved road (Latin: "via strata"), and did not have the modern association with populated areas.

History[edit]

British[edit]

The Roman road followed the broad, grassy trackway already used by the Britons for many hundreds of years, although the newer road was made to follow a more direct course. It led from Richborough in the south-east by way of a ford of the Thames at present-day Westminster to near Wroxeter, where one section went on to Holyhead and another, by way of Chester, on to Scotland.[1]

Roman[edit]

The Antonine Itinerary recorded the road as Item a vallo ad portum Ritupis "List from the wall [that is, Hadrian's wall] to the port of Richborough" and recorded the mileage as 481 Roman miles (491½ modern miles) The first scholars of the modern era assigned itinerary numbers to the 15 "Antonine" routes in Britain and they labelled this route as "Iter II". The long Iter II route from Hadrian's Wall passed through Viroconium (now Wroxeter in Shropshire), past Letocetum (modern day Wall) in Staffordshire, Manduessedum (modern day Mancetter - possible site of Boudica's last battle), Venonis (modern day High Cross) in Leicestershire, Bannaventa near Norton in modern-day Northamptonshire, Lactodorum (modern day Towcester - near another possible site of Boudica's last battle), then through Stony Stratford and Magiovinium (Fenny Stratford) in modern-day Milton Keynes, Durocobrivis (modern day Dunstable) in Bedfordshire (where it crosses the even older Icknield Way), Verulamium (near modern-day St Albans in Hertfordshire) and London (by way of the ford at Thorney Island until London Bridge was finished, and the line of the modern Old Kent Road[2]) to Rutupiae (now Richborough in Kent) on the southeast coast of England. While another section of Iter II linked Wroxeter to Chester, and other roads were built into north Wales and central Wales, these are not generally considered to be part of Watling Street. Iter III covers just one section of the whole road, for travellers between London and the port of Dover only.

Main section[edit]

The main section of the road is that from Dover to Wroxeter. It was named Wæcelinga Stræt by the Anglo-Saxons, meaning "the paved road pertaining to the people of Wæcel". Wæcel could, possibly, be a variation of the Old English word for 'foreigner' which was applied to the Celtic people inhabiting what is now Wales[citation needed]. This place-name element also gave us the name for Wæclingacaester (the early English name for Verulamium) and it seems likely that the road-name was originally applied first to the section between that town and London before being applied to the entire road[citation needed].

A number of ancient names that contain the Old English element stræt testify to the ancient route of Watling Street: Boughton Street, Kent; Colney Street, Hertfordshire; Fenny Stratford, Stony Stratford and Old Stratford, all in Buckinghamshire; Stretton under Fosse and Stretton Baskerville, both in Warwickshire; the three adjacent settlements of All Stretton, Church Stretton and Little Stretton in Shropshire; and Stretton Sugwas, Herefordshire.

Subsidiary routes[edit]

Stone Street ran south for some 12 miles from Watling Street at Canterbury (the Roman Durovernum) to Lympne (Lemanis) at the western edge of the Romney Marsh. Most of it is now the current B2068 road that runs from the M20 motorway to Canterbury.

Another Stone Street from Magnis (Kenchester) in modern Herefordshire to Caerleon, Isca Augusta and the main Roman legionary base in the south of Roman Wales.

Battle of Watling Street[edit]

Part of the route was the site of the Roman victory at the Battle of Watling Street in 61 AD between the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and the Briton leader Boudica.

Danelaw[edit]

In the 9th century, Watling Street was used as the demarcation line between the Anglo-Saxon and Danish-ruled parts of England. The Treaty of Wedmore required the defeated Danes to withdraw to an area north and east of Watling Street, thus establishing the Danelaw.

Chaucer's Pilgrims[edit]

Like most of the Roman road network, the Roman paving fell into disrepair when the Romans left Britain, although the route continued to be used for centuries afterwards. It is likely that Chaucer's pilgrims used Watling Street to travel from Southwark to Canterbury in his Canterbury Tales.

Turnpike[edit]

The road north of London became a Turnpike firstly in 1707 when the section from Fourne hill north of Hockliffe to Stony Stratford was paved following an Act of Parliament on March 4, 1707.[3]

This was the first Turnpike Trust and showed how financially hazardous the undertaking could be.

The Fourne hill to Stony Stratford case provides more evidence that Parliament would void undertakers’ rights if they were negligent. The trustees for the Fourne hill to Stony Stratford road borrowed more than 7000 pounds in 1707 and 1708 to improve the road. The creditors, however, claim to have been misinformed regarding the expected revenues from the tolls, and requested in 1709 that a new act extend the term and increase the tolls. A new act was passed in 1709 extending the term, but the tolls were not increased. It also included a provision that the creditors could take receivership of the tolls if the trustees had not repaid their debts by 1711.

Apparently, the trustees were unable to borrow and the creditors took over the tolls. In 1716, Parliament tried to clarify the situation by passing an act that vested authority in the trustees from the 1709 act and another group appointed by the Justices of the Peace for Buckinghamshire.

The 1716 act was not amended for its entire term of 23 years, but once it was set to expire, Parliament decided that it would not renew the rights of the existing trustees for the Fourne hill to Stony Stratford road. In 1736, the trustees submitted a petition for an extension of their rights, but it failed to pass and in 1739 their authority ended. In 1740, a new act was passed naming a replacement body of trustees. In the petition for the new bill, the inhabitants of Buckinghamshire described the road as being ‘ruined.’ This sentiment was affirmed by the

Member heading the committee for the bill.[4]

The road was re-paved in the early 19th century by Thomas Telford who brought it back into use as a turnpike road for use by mail coaches bringing mail to and from Ireland, his road being extended to the port of Holyhead on the Isle of Anglesey in Wales. At this time the section south of London became known as the Great Dover Road. The toll system ended in 1875.

Modern road[edit]

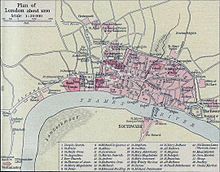

Most of the road is still in use today, apart from a few sections where it has been diverted. The stretch of the road between London and Dover is today known as the A2, and the stretch between London and Shrewsbury is today known as the A5 (which now continues to Holyhead). The sections of the road which pass through Central London are known by a variety of names, including Edgware Road and Maida Vale. At Blackheath the Roman road ran along Old Dover Road, then turning and running through Greenwich Park to head to a location perhaps a little north of the existing Deptford Bridge. Through Milton Keynes, the A5 is diverted onto a new dual-carriageway and Watling Street forms part of the new town's grid system and carries the additional designation V4.

Continued use of the name along the ancient road[edit]

The use of the street name is retained along the ancient road in many places: for instance, to the south east of Roman London and on into Kent (including the towns of Canterbury, Gillingham, Rochester, Gravesend, Dartford, and Bexleyheath). Within London, a major road joining the A5 in north west London is called Watling Avenue. North of London, the name Watling Street still occurs in Hertfordshire (including St Albans), Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire (including Milton Keynes), Northamptonshire (including Towcester), Leicestershire, Warwickshire (including Nuneaton), Staffordshire (including Cannock, Wall and Lichfield), Shropshire (including in Church Stretton as the residential Watling St North and South) and Gwynedd.

A section of Watling Street still exists in the City of London close to Mansion House underground station on the route of the original Roman road which traversed the River Thames via the first London Bridge and ran through the City in a straight line from London Bridge to Newgate.

Other Watling Streets[edit]

In Lancashire, Watling Street is the Roman Road through Affetside which leads from Manchester to Ribchester.

The Roman Road from Cataractonium (now Catterick, North Yorkshire) to Corstopitum (now Corbridge, Northumberland) and on to the Antonine Wall (also known as Grym's Dyke or Graham's Dyke, from Grim, a name of Woden [5][6][7]) also came to be known as Watling Street,[8] with perhaps a similar Old English etymology owing to its path into the foreign land of Scotland. This route is also known as Dere Street. This may also be the case for another Watling Street[8][9] between Manchester (Mamucium) and Ribchester (Bremetennacum) which ultimately led to another 'foreign land' in Saxon times, that of Rheged or modern Cumbria.

A Watling Street Road exists to this day in the city of Preston, Lancashire. It connects the districts of Ribbleton and Fulwood and passes the site of Sharoe Green Hospital.

See also[edit]

- Great Dover Road

- Roman Britain

- Roman roads in Britain

- Fenny Stratford (Magiovinium)

- Towcester (Lactodorum)

- Bannaventa

- Tripontium

- Manduessedum

Notes[edit]

- ^ Ditchfield, Peter Hampson (1901). English Villages. London: Methuen. p. 33.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Margary, Ivan D. (1948). Roman Ways in the Weald (third ed.). London: J. M. Dent. p. 126.

- ^ "House of Lords Journal Volume 18". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bogart, Dan (2007). "Evidence from Road and River Improvement Authorities, 1600-1750" (PDF). Political Institutions and the Emergence of Regulatory Commitment in England. University of California. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Earthwork of England: prehistoric, Roman, Saxon, Danish, Norman and mediæval - Page 496, by Arthur Hadrian Allcroft

- ^ 'Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club - Page 255, by Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club, Hereford, England, G. H. Jack, 1905

- ^ 'The place-names of England and Wales' - Page 281, by James Brown Johnston - Family & Relationships - 1916

- ^ a b Map of Roman Roads in Britain

- ^ Bury Metropolitan Council - History

References[edit]

- O. Roucoux, The Roman Watling Street: from London to High Cross, Dunstable Museum Trust, 1984, ISBN 0-9508406-2-9.

External links[edit]

- The Antonine Itinerary

- 'Watling Street - A Journey through Roman Britain' web page by the BBC

- Stone Street, Suffolk - Thayer