User:Nikkilongua/End of the Trail (Fraser)

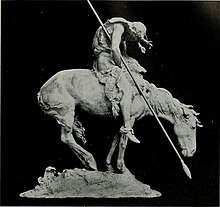

The End of the Trail is a sculpture by James Earle Fraser, the original plaster model is located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States. It depicts a weary Native American man, wearing only the remains of a blanket and carrying a spear. He is hanging limp as his weary horse with swollen eyes comes to the edge of the Pacific Ocean. The wind blowing the horse's tail suggests they have their backs to the wind.[1] The Indian in the statue is modeled by Seneca Chief John Big Tree, and the horse was adapted from the horse figure in another work, In the Wind. The statue is a commentary on the damage Euro-American settlement inflicted upon Native Americans. The main figure embodies the suffering and exhaustion of people driven from their native lands. [2]

Fraser felt a connection to the Native American heritage, which influenced the creation of the End of the Trail. He felt attached to this particular work, making several models of it throughout his life. The sculpture gained national popularity after being presented at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, causing the image of the weary Indian and his horse to become a recognizable symbol throughout America associated with westward expansion and the destruction of the Native Americans' way of life. The statue has been relocated multiple times before being placed at its permanent home at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Museum. The statue has been criticized for the manner in which is depicts Native Americans as a dying race. However, Fraser intended for the work to be a critique of the United States government.[3]

Background[edit]

Fraser first modeled the End of the Trail based on his experience as a boy in the Dakota Territory. Living on the Indians' land, Fraser witnessed their simple way of living, in small villages, hunting and trading. His memoirs state, "as a boy, I remembered an old Dakota trapper saying, 'The Indians will someday be pushed into the Pacific Ocean ". Later he stated "the idea occurred to me of making an Indian which represented his race reaching the end of the trail, at the edge of the Pacific".[4]

Fraser made several other famous American works, some inspired by his experiences with Native Americans. Besides the End of the Trail, Fraser's next famous work is the Buffalo-Indian Head nickel created in 1913 to become America's standard five cent coin. Asked to create something uniquely American, Fraser thought the buffalo and American Indian were integral parts of American culture and history. Another artwork influenced by the Indians made by Fraser is called The Buffalo Prayer. [5]

Design and Construction[edit]

Fraser created the first model of End of the Trail in 1894 at the age of 17. The design was inspired by a piece of art Fraser saw at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The original model was exhibited at a competition sponsored by the American Art Association, winning first place. [6] Over the years, Fraser created several renditions of the model trying to perfect it. With the assistance of his wife, Laura Gardin Fraser, he created a two and a half times life size model of the statue on an eight foot pedestal out of plaster. This large plaster version of the work was displayed at the 1915 Panama- Pacific International Exposition in San Fransisco and was awarded the gold medal, gaining the work nation wide attention.[7]

Location[edit]

After the exposition closed, plans to place a bronze version of the statue on the Pacific Palisades were halted due to the United States' involvement in World War I. Resources like metal were scarce, and it was unlikely that the End of the Trail could be cast in bronze. The monument was thrown in a mud pit in Marina Park, along with the other artwork displayed at the exposition. The Tulare County Forestry Board purchased and rescued the statue in 1919, and transported it to Mooney Grove Park in Visalia, California, where other famous sculptures are located, like the Pioneer by Solon Borglum. Fraser was unaware of the whereabout of the statue until 1922. [8]

After Fraser's death in 1953, plans were in motion to create a Fraser Memorial Studio in the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The museum considered it imperative to have Fraser's most renowned work, End of the Trail, featured. Associates of the museum made an agreement with Tulare Country, the original End of the Trail statue would be moved to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Museum and a replica would be drafted to return to Mooney Grove Park, at the expense of the museum. Great controversy surrounded the moving of the statue, as the residents of Visalia as well as some art professionals felt that statue should remain where it had been for the past 50 years. The statue was in poor condition, there were large surface cracks and major deterioration, and Tulare Country was unable to accumulate the funds to preserve it, so ultimately the trade was made.[8]

Restoration[edit]

Being located outside for such a long period of time, the statue had been exposed to all sorts of weather and elements. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum removed six layers of paint and closed fissures in the body of the horse. Enlarged photos of the Native American's head and other details of the artwork were created to ensure the statue was restored to its original appearance. According to artist Leonard McMurry, who was responsible for the restoration, facial features like the chin and the upper chest were most difficult to recreate. The surface of the statue was refined to make the surface ready for molds to be made. The restoration of the End of the Trail was finished in 1971.[9]

Replicas[edit]

After the Panama- Pacific International Exposition, Fraser was initially unsuccessful at gaining support to have a bronze casted version of End of the Trail created. Clarence A. Shaler, a wealthy art enthusiast, saw the monument at the exposition and took interest in it. He agreed to commission the bronze cast statue in 1926. Fraser and Shaler compromised on the creation of a life sized bronze statue. The statue was unveiled on June 23, 1929, and donated to Waupun, Wisconsin as a tribute to the Native Americans. Fraser said it was "fitting that in Wisconsin, where the Indian made one of his last stands...I could offer this slight tribute to his memory". The Waupun statue was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[10]

The National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Museum had molds created from the original End of the Trail statue to create a bronze version to give to the city of Visalia. This version of the statue was funded by the museum. The bronze casted replica was replaced on a pedestal in Mooney Grove Park in 1971.[11]

A National Symbol[edit]

Beside these two famous replicas, the image of the exhausted Indian slouching over his horse became a recognizable symbol across America. Following the exposition in San Francisco, depictions of the famous image were sold on prints, miniatures, and postcards. The pose itself became widely known, being recreated at traveling shows and rodeos. [12] A painting of the statue's image appeared on the original cover of the 1971 album Surf's Up by the Beach Boys. Many copies of the 1915 statue are on display elsewhere, including one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, another in the library at Winona State University in Fraser's hometown of Winona, Minnesota, and a 1929 monument at the Riverside Cemetery in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.[13]

Criticism[edit]

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition catalog described the End of the Trail as "a reminiscence of early American history and its traditions of courage and endurance, and the pathos of the Indians's decline".[14]

The End of the Trail sculpture can be interpreted in different ways. It is possible for the artwork to be viewed as romanticizing American values of "courage and endurance" in the defeat of the Native Americans. The sculpture can also be seen from the perspective of appreciating the lost heritage of the Native Americans and acknowledging their fighting spirit.[15]

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition faced criticism on its promotion of the assimilation of Indians into American culture and the sculptures' depiction of Native Americans as a vanishing race. Some critics argued that the End fo the Trail reinforces the "vanishing race myth", by supporting the notion that the Native Americans were destined to die out, as it was necessary for the progress of America.[14] Jeffery Gibson, a sculpture with American Indian heritage says in an interview with art research associate Shannon Vittoria, "I saw [End of the Trail] as an image of a shamed, defeated Indian. It always made me feel badly about myself, and I wondered if this was this really how the rest of the world viewed us, as failures. It seemed to be an image about defeat and despair". [16]

Others saw the work as an indictment of the government destroying an entire culture.[14] According to Alan Trachtenberg, in the years following the exposition, a change of perspective occurred in which Indians were viewed as "noble but still doomed 'First Americans' " , as Americans began to appreciate their differences and respect their way of life. [16]

References[edit]

- ^ Vittoria, Shannon (19 February 2014). "End of the Trail, Then and Now". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Fraser, James Earle (1969). James Earle Fraser, American sculptor: A Retrospective Exhibition of Bronzes from Works of 1913 to 1953: June 2nd, to July 3rd, 1969. Kennedy Galleries. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Krakel, Dean (1973). End of the Trail, The Odyssey of a Statue. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Vittoria, Shannon (19 February 2014). "End of the Trail, Then and Now". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Fraser, James Earle (1969). James Earle Fraser, American sculptor: A Retrospective Exhibition of Bronzes from Works of 1913 to 1953: June 2nd, to July 3rd, 1969. Kennedy Galleries. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Fraser, James Earle (1969). James Earle Fraser, American sculptor: A Retrospective Exhibition of Bronzes from Works of 1913 to 1953: June 2nd, to July 3rd, 1969. Kennedy Galleries. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Krakel, Dean (1973). End of the Trail, The Odyssey of a Statue. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 1–20.

- ^ a b Krakel, Dean (1973). End of the Trail, The Odyssey of a Statue. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Krakel, Dean (1973). End of the Trail, The Odyssey of a Statue. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Shoptaugh, Terry L. (1980). "Nomination Form - End of the Trail". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Krakel, Dean (1973). End of the Trail, The Odyssey of a Statue. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Leatherwood, Grant (March 24, 2023). "The End of the Trail as an American Icon". The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

- ^ Farris, Kyle (December 1, 1969). "'End of the Trail' finds new home: Winona State leaders plan to move sculpture to Krueger Library, add context". Winona Daily News. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c Tolles, Thayer (2013). The American West in Bronze, 1850-1925. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Mark Polizzotti. pp. 48–51. ISBN 9780300197433.

- ^ Markwyn, Abigail (April 1, 2016). "Beyond The End of the Trail: Indians at San Francisco's 1915 World's Fair". Ethnohistory. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Vittoria, Shannon (19 February 2014). "End of the Trail, Then and Now". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

External links[edit]

Media related to End of the Trail at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to End of the Trail at Wikimedia Commons

| This is a user sandbox of Nikkilongua. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |