User:Nancy/WIP/CDM

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | cultural: i, ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 770 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

The Canal du Midi is a 240 km (150 mi) long canal in Southern France (French: le Midi). The canal connects the Garonne River to the Étang de Thau on the Mediterranean and along with the Canal de Garonne forms the Canal des Deux Mers joining the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. The canal runs from the city of Toulouse down to the Mediterranean port of Sète—which was founded to serve as the eastern terminus of the canal. Originally named the Royal Canal (French: canal royal en Languedoc) it was renamed Canal du Midi during the French Revolution in 1789.

The construction of the canal was motivated by the wheat trade. Built in the seventeenth century, from 1666 to 1681, during the reign of Louis XIV and under the supervision of Pierre-Paul Riquet, the canal du Midi is the oldest canal in Europe still in use.

Since 1996 the canal has been designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Introduction[edit]

Location and profile of the canal[edit]

The canal du Midi is located in the south of France and runs through the departments of the Hérault, the Aude and Haute-Garonne. From its eastern end at Marseillan where it empties in to the étang de Thau near Sete to the western port de l'embouchure in Toulouse, the canal is 241 kilometers in length.

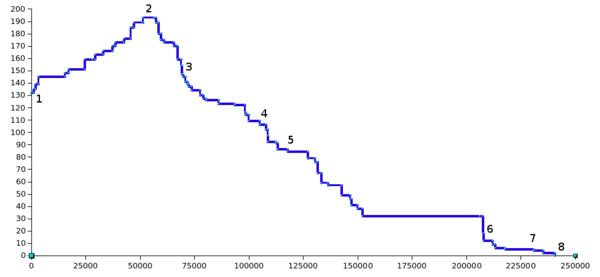

The Canal du Midi is a classic summit-level canal with an upwards slope on the Atlantic side of 52km and a descent to the Mediterranean of 189km with a summit level at seuil de Naurouze. The channel depth averages 2m but can be as little as 1.8m, the maximum allowed draft for craft on the canal is 1.6m. The width of the channel at its base is 10m.

The graph shows the profile of the Canal du Midi from Toulouse (1), through the seuil de Naurouze (2), Castelnaudary (3), Carcassonne (4), and Trèbes (5). The canal continues to Beziers just after the Fonserannes Lock (6) and contiunues to Agde (7) before ending in Sète at the étang de Thau.

At 53.49km the Long Pound from Argens Lock to Fonserannes Lock is the longest reach whilst the shortest is 250m between the two locks at Fresquel.

Status[edit]

For historical reasons the Canal du Midi has a unique legal status which was codified in 1956.

History[edit]

The original purpose of the Canal du Midi was to be a shortcut between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, avoiding the long sea voyage around hostile Spain, Barbary pirates, and a trip that in the 17th century required a full month of sailing. The strategic value of this is obvious and it had been discussed for centuries, in particular when King Francis I brought Leonardo da Vinci to France in 1516 and commissioned a survey of a route from the Garonne at Toulouse to the Aude at Carcassonne. The major problem that this and subsequent planners had during the next 150 years was how to supply the summit sections with enough water.[1] [2] [3]

This was the problem that Pierre-Paul Riquet, a rich tax-farmer in the Languedoc region, who knew the region intimately, believed in 1662 that he could solve. He first had to persuade Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the finance minister of Louis XIV which he did through his friendship with the Archbishop of Toulouse. A Royal Commission was appointed and in 1665 recommended the project which was finally ordered by Louis XIV in 1666 with the possible expenditure of 3,360,000 livres. The specifications for the work were drawn up by the head of this commission and France's leading military engineer in that period, the Chevalier de Clerville, who remained a loyal ally of Riquet and partisan of the Canal du Midi until his death.[1][2][3] To help in the design, Riquet is said to have constructed a miniature canal in the grounds of his house, Bonrepos, complete with locks, weirs, feeder channels and even a tunnel.[1]

At the age of 63, Riquet started this great enterprise, sending his personal engineer, François Andreossy, and a local water expert, Pierre Roux, to the Montagne Noire to work on the water supply. Some of Clerville's men with experience in military engineering came, too, to build a huge dam at Saint Ferréol on the Laudot river. The Laudot was a tributary of the River Tarn in the Montagne Noire some 20 km (12 mi) from the summit of the proposed canal at Seuil de Naurouze. This massive dam, 700 meters (2,300 ft) long, 30 meters (98 ft) above the riverbed and 120 meters (390 ft) thick at its base was the largest work of civil engineering in a the century in Europe and only the second major dam to be built in Europe, after one in Alicante in Spain. The newly built body of water, the Bassin de St. Ferréol, was connected to the Canal du Midi with a contoured channel over 25 km long, 3.7 m (12 ft) wide with a base width of 1.5 m (4.9 ft). It was eventually outfitted with 14 locks in order to bring building materials for the canal down from the mountains and to create a new port for the mountain town of Revel. This supply system successfully fed the canal with water where it crossed the continental divide, replacing water that drained toward the two seas. The system was a masterpiece of both hydraulic and structural engineering, and served as an early ratification of Riquet's vision. It was also a major part of a massive enterprise. At the peak of the work, there were 12,000 labourers on the project including over a thousand women, many of whom came specifically to work on the water system.[1][2][3]

The women laborers were surprisingly important to the canal's engineering. Many of them came from towns in the Pyrenees that were former Roman bath colonies, where elements of classical hydraulics had been maintained as a living tradition. They were hired at first to haul dirt to the dam at St. Ferréol, but their supervisors, who were struggling to design the channels from the dam to the canal, recognized their expertise. Engineering in this period was mainly focused on fortress construction, and hydraulics was concerned mostly with mining and problems of drainage. Building a navigational canal across the continent was well beyond the formal knowledge of the military engineers expected to supervise it. But the peasant women who were carriers of classical hydraulic methods, added to the repertoire of available techniques. They not only perfected the water supply system for the canal, but also threaded the waterway through the mountains near Béziers, using few locks, and built the eight-lock staircase at Fonserannes.[2]

Abandoned projects[edit]

Project planning[edit]

Politics and economics[edit]

The edict of Louise XIV and financing[edit]

Building the canal[edit]

Opening[edit]

The Canal du Midi was opened officially as the Canal Royal de Languedoc on May 15, 1681.[1] It was also referred to as the Canal des Deux Mers (Canal of Two Seas). It eventually cost over 15 million livres, of which nearly 2 million came from Riquet himself, leaving him with huge debts and he died in 1680, just months before the Canal was opened to navigation. His sons inherited the canal, but the family's investments were not recovered and debts not fully paid for until over 100 years later. The canal was well tended and run as a paternalistic enterprise until the revolution.

Later alterations and additional works[edit]

Operation of the canal[edit]

Competition from the railways[edit]

Commercial traffic[edit]

The canal in the 21st Century[edit]

Structures[edit]

Water supply[edit]

Locks[edit]

The canal as a whole was built on a grand scale with locks of length 30.5 m (100 ft) oval in construction, being 6 m (20 ft) wide at the gates and 11 m (36 ft) wide in the middle. This design was intended to resist the collapse of the walls that happened early in the project. The oval locks used the strength of the arch against the inward pressure of the surrounding soil that had destabilized the early locks with straight walls.[1] Such arches had been used by the Romans for retaining walls in Gaul, so this technique was not new, but its application to locks was revolutionary and was imitated in early American canals.[2][3] Many of the structures were designed with neoclassical elements to further and echo the king's ambitions to make France a New Rome. The Canal du Midi as a grand piece of infrastructural engineering in itself was promoted as worthy of Rome and the political dreams behind it were clarified with plaques in Latin, and walls built with Roman features.[2]

Ports[edit]

Aqueducts[edit]

Many aqueducts were constructed along the route of the Canal du Midi. Originally the canal crossed most of the rivers in its path at level but this can disrupt the flow of the canals and may cause flooding when the river is in spate. It can also cause problems with silting. Some aqueducts on the canal date from the time of Riquet but most were built as a result of the later recommendations by Vauban. The aqueducts on the canal from west to east are:

- Hers Aqueduct

- Fresquel Aqueduct, built in at the start of the 19th Century and opened in 1810 in order to take the canal through the city of Carcassonne.

- Orbiel Aqueduct

- Ognon Aqueduct

- Répudre Aqueduct, built between 1667 and 1676 to cross the Répudre to the east of the village of Paraza. The aqueduct is 135m long and is erroneously credited in many publications as the world's first aqueduct. It is however the first aqueduct built be Riquet.

- Cesse Aqueduct

- Orb Aqueduct, opened in 1857 enabling vessels to avoid the short but dangerous passage down 200m of the Orb in the centre of Beziers.

Other structures[edit]

There are many other noteworthy structures along the canal:

- The Malpas Tunnel on the Long Pound south-east of the Oppidum d'Ensérune is 165m long and boars through a 50m hill. At the time it was an astonishing feat of engineering which many doubted Riquet could achieve.

- The epanchoir Argent-Double at La Redorte

- The Fonserannes water slope

Flora and fauna[edit]

Influence[edit]

Key personnel[edit]

- Pierre-Paul Riquet concieved, designed and built the canal. He obtained fromt the King the ownership and operation of the Canal du Midi in life for himself and his descendants. He died in October 1680 before the waterway was completed.

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert was King Louis XIV's Minister of Finance and was responsible for assessing the cost and feasibility of the project.

- Sébastien de Vauban was an engineer and architect appointed by the king who made many improvements to the Canal du Midi between 1685 and 1686.

- François Andréossy collaborator/partner of Pierre-Paul Riquet. He managed the work and assisted in all activities. He assured the completion of the canal after the death of Pierre-Paul Riquet.

- Louis Nicolas de Clerville was a French engineer who controlled and monitored progress. He helped and advised Riquet during construction

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Rolt, L. T. C. (1973). From Sea to Sea: An Illustrated History of the Canal du Midi. Allen Lane. ISBN 2-910185-02-08.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Chandra Mukerji, Impossible Engineering Princeton: Princeton University Press

- ^ a b c d Jean-Denis Bergasse Le Canal du Midi Cessenon: J-D Bergasse 1982-1984.