User:Music&gardens/sandbox

Subsistence practices of North West Coast First Nations[edit]

Both the sea and the land provided important sources of food and raw materials to Indigenous Peoples of the Northwest Coast, and many of these resources needed to be managed to ensure continual harvest. Historians and ethnographers provide evidence of cultivation practices and environment management strategies that have been used by First Nations peoples for centuries along the Northwest Coast.[1] Practices like digging and tilling, pruning, controlled burning, fertilizing, streamscaping and habitat creation allowed Indigenous groups to intentionally manage the environment around them in order to encourage greater production of a resource for sustained harvesting.[2]

Resource enhancement strategies:[edit]

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast harvested root crops and shellfish through a process of digging and tilling. Using a digging stick made from hard wood, First Nations people would work the ground between tree roots and in bulb and rhizome patches, which loosened the compacted soil. Loosened soils made it easier to remove root crops whole and undamaged,[3] and allowed roots, bulbs and rhizomes to grow more freely and abundantly with increased production.[4]

Weeding, like digging and tilling, allowed the desired resource to expand throughout the area because it removed plants competing for the same space and nutrients.[5][6] Weeding also improved plant growth by ensuring soil nutrients would only go to those plants intended for harvest. Ethnobotanists have found evidence of wapato (a tuber), camas (a bulb), and root crops like potentilla, trillium, and sea milkwort growing beyond their natural habitat due to First Nations management of these resources. [7]

Pruning was another cultivation method practiced by Indigenous peoples. Pruning could be accomplished in two ways. Kwakwaka’wakw Elders described pruning wild berry bushes by breaking entire branches off the plant when harvesting. This promoted more branch growth, and therefore more berries, the following year.[8] The Sto:lo Nation used controlled burning to prune plants.[9]

Controlled burning was a method of pruning, but also an environment management strategy with multiple benefits. Burns forced desired plants to produce new growth, which would often be more vigorous and lush and would provide a greater harvest in following years.[10] Burns weeded the ground by removing ground covers and other undesired plants from a resource environment. And burns helped control predators. The Sto:lo used controlled burning to kill off insect pests and diseases so they wouldn’t affect future harvests, but burns also removed animal habitat which discouraged animal pests from living near and preying on resources used by Indigenous peoples.[11] Burning was also a method of fertilizing the soil, as the burnt plant matter added nutrients.[12] Along with burnt and rotted wood, Indigenous peoples like the Heiltsuk added seaweed, clamshells, and fish and animal remains to soils to provide nutrients for their plants and increase plant growth.[13]

Transplanting, which involved moving resources from one location to another, was a First Nations strategy used to increase both land and aquatic resources. The Tsimshian dug up plants and moved them to sites nearer a village for easier maintenance, ease of access, and to replace old, unproductive plants.[14] Ethnographic records show that fish eggs (especially salmon and herring) were also transplanted for similar reasons. Transplanting fish eggs to a nearby stream brought a resource closer to a village, and could replenish fish stocks in rivers that had been depleted.[15]

Transplantation success was ensured by First Nations' environment manipulation. “Streamscaping” refers to the Indigenous practice of clearing streams by removing obstructions like rocks and beaver dams to enhance river flow and create a clear path for salmon runs.[16][17] The Tlingit built redds to ensure a safe and healthy habitat for the transplanted eggs.[18] Tidal areas like beaches and estuaries were also managed to increase resource harvests. Archeological evidence shows that coastal First Nations created and tended clam gardens. Coastal Peoples cleared the sand of stones, which made the ground easier to dig during harvest, and built stone walls along the tidal line to encourage sediment to build up in the clam bed. These modifications made harvesting clams easier and expanded clam habitat which increased the harvest.[19] Estuaries, or salt marshes, were similarly managed by the Kwakwaka’wakw to increase harvest of delicate roots of clover, rice-root lily, and silverweed.[20] The Kwakwaka’wakw built stone walls on the low side of a graded estuary which allowed sediment to accumulate and extended the growing habitat required for these roots. Along with removing competing species through weeding, the Kwakwaka’wakw expanded the habitat zone for these plants significantly, and with it, the harvest.[21]

Indigenous peoples ensured local sources of flourishing resources and reliable harvests in these ways.[22]

Harvest management:[edit]

Along with managing the environment, Indigenous peoples used harvest management practices to maintain sustainability.

Indigenous peoples practiced selective harvesting, a harvest management principle which ensured continuation of a food supply in a variety of ways. For example, during harvest the vegetative parts of a plant might be used while the flowering stalks would be left to flower and produce seed. Immature fish, clams, and bulbs would be replaced or replanted by Indigenous peoples to continue growing. When harvesting root crops, Northwest Coast First Nations would replant parts of the root, or leave some roots unharvested.[23] In the case of the cedar tree, which was widely abundant along the Northwest Coast and was a significant part of the subsistence of Indigenous peoples living there, only a few roots would be harvested from each tree so that tree would be undamaged.[24]

With regards to timber and bark collection, Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast practiced partial harvesting. Partial harvesting meant only removing a portion of the tree or bark so that the growth of the tree wouldn’t be hindered.[25][26] Ethnobotanists have discovered many old-growth cedar trees that act as successful evidence of this practice, trees that despite having wood or bark removed have healed and continued to live.[27]

Harvesting crops seasonally allowed plants time to continue growing,[28] while rotating harvest locations allowed resources time to recover as Indigenous groups rotated through different locations to obtain the same resource.[29][30] These practices made harvesting sustainable.

Indigenous land tenure was a way of managing harvests through ownership.[31] Responsibility of a resource like berry and root patches, stands of trees or seaweeds, and sections of streams, included caring for that resource as well as harvesting from it sustainably, and was the job of the village or family that the resource belonged to. Tenure was a way of ensuring people took care of local resources.[32][33] Indigenous resource ownership also provided economy, as excess resources produced within a family or village could be traded for hard-to-obtain resources from other villages and regions. This trade economy balanced plentiful harvests by spreading them between different Nations.[34]

First Nations technologies and uses:[edit]

Though most harvesting was done by hand, specific technologies used by Indigenous peoples helped make the jobs of harvesting and processing resources easier.[35]

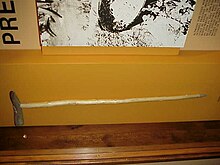

Digging sticks were strong, carved digging implements made from a hard wood like yew, that was strengthened by being heated over fire and rubbed with tallow and oil.[36] Different styles of digging sticks were used by Northwest Coast Peoples to dig, till, loosen soil, and harvest different types of root, bulbs, rhizomes, and shellfish.[37]

Baskets woven from cedar bark, withes, and grasses could be made in varying weaves, some so tight they could carry water. First Nations women and children often used baskets to carry or store harvests of berries, roots, and fish.[38]

Snares made of cedar withes were used by First Nations hunters for trapping goats and other land animals.[39]

Various types of hooks, nets, traps, and harpoons were used to fish and hunt aquatic resources.[40] Other tools like fishing weirs helped in the collection of salmon by creating a barrier that held the salmon in one location so they could be harvested.[41]

These technologies were also part of sustainable harvesting - net gauges were used to make netting of specific sizes designed to catch only one type or one size of fish.[42] Fish weirs and traps had gates that could be left open or removed to allow salmon to complete their run once the harvest was over.[43][44]

Drying racks and bentwood boxes made of cedar were used to dry, process, cook, or store roots, berries, meats, and other harvests.[45] Cedar, which is naturally resistant to rot, durable and easy to work,[46] was an ideal wood for storage containers and could be bent with steam to make strong, solid containers from a single plank of wood.[47]

Indigenous peoples also made their own tools from stone, wood, shells and bone.[48] Tools like adze, mauls, chisels, and wedges were used to cut, grind, carve and work wood. Other tools like bark shredders and mat creasers were used to work more pliable materials like barks and grasses to make clothing, baskets, and mats.[49]

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast employed extensive resource management strategies for their subsistence. By using a variety of cultivation practices, strategies, and technologies to manage the environment and the harvest, Indigenous peoples were able to enhance and maintain vital land and marine resources along the Northwest Coast.[50]

- ^ Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (2005). "Chapter 1: Introduction Reconstructing Indigenous Resource Management, Reconstructing the History of an Idea". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Deur and Turner 2005, p.16.

- ^ Deur, Douglas (2005). "Chapter 11: Tending the Garden, Making the Soil (Northwest Coast Estuarine Gardens as Engineered Environments)". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. p. 314. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Turner, Nancy J; Peacock, Sandra (2005). "Chapter 4: Solving the Perennial Paradox (Ethnobotanical Evidence for Plant Resource Management on the Northwest Coast)". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.117.

- ^ Deur 2005, p.307.

- ^ Deur 2005 p.304.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.120.

- ^ Lepofsky, Dana; Hallett, Douglas; Lertzman, Ken; Mathewes, Rolf; McHalsie, Albert (Sonny); Washbrook, Kevin (2005). "Chapter 8: Documenting Precontact Plant Management on the Northwest Coast (An Example of Prescribed Burning in the Central and Upper Fraser Valley, British Columbia)". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Lepofsky et al. 2005, p.226.

- ^ Darby, Melissa (2005). "Chapter 7: The Intensification of Wapato (Sagittaria latifolia) by the Chinookan People of the Lower Columbia River". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Lepofsky et al. 2005, p.226.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.118.

- ^ McDonald, James (2005). "Chapter 9: Cultivating in the Northwest Early Accounts of Tsimshian Horticulture". In Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (eds.). Keeping it living Traditions of plant use and cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. UBC Press. p. 245. ISBN 0-295-98565-8.

- ^ Lepofsky, Dana; Caldwell, Megan (2013). "Indigenous marine resource management on the Northwest Coast of North America". Ecological Processes. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/2192-1709-2-12. ISSN 2192-1709.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Thornton, Thomas; Deur, Douglas; Kitka, Herman (2015). "Cultivation of Salmon and other Marine Resources on the Northwest Coast of North America". Human Ecology. 43 (2): 192. doi:10.1007/s10745-015-9747-z. ISSN 0300-7839.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.7.

- ^ Thornton et al 2005, p.195.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.7.

- ^ Deur 2005, p.304.

- ^ Deur 2005, p.313.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.118.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.114.

- ^ Stewart, Hilary (1984). Cedar : tree of life to the Northwest Coast Indians. Seattle [Washington]: University of Washington Press. pp. 18–27.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.123.

- ^ Stewart 1984, p.36-44.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.123.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.114.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.113.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.6.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.7.

- ^ Deur 2005, p.304.

- ^ Darby 2005, p.206.

- ^ Darby 2005, p.207-208.

- ^ Turner, Nancy J., (1998). Plant technology of First Peoples in British Columbia. Turner, Nancy J., 1947-, Royal British Columbia Museum. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 35. ISBN 0774806877. OCLC 40052607.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boas, Franz (1921). Ethnology of the Kwakiutl,based on data collected by George Hunt. Washington Government Printing Office. pp. 146–151.

- ^ Boas 1921, p.186-204.

- ^ Boas 1921, p.198-221.

- ^ Boas 1921, p.173.

- ^ Boas 1921, p.151-153.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.3.

- ^ Thornton et al 2015, p.192.

- ^ Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013, p.8.

- ^ Thornton et al 2015, p.192.

- ^ Boas 1921, p.166-171.

- ^ Stewart 1984, p.18-27.

- ^ Stewart 1984, p.84.

- ^ Stewart 1984, p.29-35.

- ^ Stewart 1984, p.123-127.

- ^ Turner and Peacock 2005, p.146