User:Mliu92/sandbox/Baker-Barry Tunnel

Eastern end and portal (1993) | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°50′27″N 122°29′26″W / 37.840748°N 122.490448°W |

| Status | Active |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 1917 |

| Opened | 1918 |

| Rebuilt | 2017 |

| Traffic | 600 (2008) |

| Technical | |

| Length | 2,363 ft (720 m)[1] |

Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite | |

| Nearest city | Sausalito, California |

| Area | 25 acres (10 ha) |

| Built | 1867 |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000255[2] |

| Added to NRHP | December 12, 1973 |

The Baker–Barry Tunnel connects the former military bases Fort Barry and Fort Baker in the Marin Headlands of Marin County, California. The bases are now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. The tunnel is also known as the Bunker Road Tunnel for the road that runs through it, or as the Five-Minute Tunnel because it is only wide enough to accommodate a single reversible lane, opened to traffic at either end for five minute intervals.

History[edit]

Although geographically close, Forts Baker (on the east) and Barry (on the west) are separated by steep terrain. Travel between the two forts was difficult, and was typically handled by boat. Although a "crude and treacherous" road connected the two forts by land, the post commander complained in 1911 there was no protection to keep users from falling over the side of the road. At certain parts, the road was too narrow for wagon teams to pass each other; the slope into which it was cut had a maximum grade of seventy-five percent, and falling over the side meant a drop of 400 feet (120 m). In response, the War Department allocated $1,500 for board fencing to protect road users at the most dangerous locations. Due to the danger of land travel, a separate school was established at Fort Barry in 1913.[3]

The tunnel was constructed by the U.S. Army after plans were made in 1916 to expand Fort Barry.[3] Construction started in 1917 and was complete in 1918.[4] The tunnel was rebuilt in 1925 to replace rotting timbers,[3] and in June 1937, the tunnel's width was increased to 20 feet (6 m).[5] The tunnel was listed as a contributing structure for the Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite Historic District on December 12, 1973.[4]

Surveys as early as the 1960s showed the concrete lining had cracked, and due to very long cracks, some exceeding 100 feet (30 m) long, the tunnel was closed in February 1989. Catastrophic failure was not likely, but chunks of concrete had spalled and fallen to the roadway, creating a safety hazard.[3] After a rebuild was completed in 1994, the tunnel reopened in 1995.[6][7][8]

The tunnel was again closed for repairs between January and June 2017. Workers sealed cracks in the vintage concrete to reduce seepage, repaved the road, replaced water and sewer lines, and installed energy-efficient LED lighting. Prior to the 2017 rehabilitation, the tunnel was the second-largest consumer of power in the entire Golden Gate National Recreation Area (after district headquarters in San Francisco).[9] During the shutdown, traffic was rerouted to Conzelman Road, a coastal route which is popular among tourists for scenic views of the Golden Gate.[10]

Design[edit]

- Western Portal

- Eastern Portal

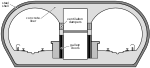

The Baker-Barry Tunnel lies beneath the U.S. 101 highway, just south of where the highway itself goes through a tunnel on the Waldo Grade. It is cut through serpentine rock and as completed in 1918, was supported with a timber structure and featured a macadam road with cobblestone gutters.[4] The cross-section of the tunnel inside the timber supports was 16 by 16 feet (4.9 m × 4.9 m). Timbers were 10 inches (250 mm) square, covered in lagging 2 inches (51 mm) thick, and supports were spaced at 5-foot (1.5 m) intervals.[3]

Electric and water lines were run through the tunnel in 1922.[11] The tunnel was rebuilt in 1925 at a cost of $16,618 after much of the lagging and timbers had rotted due to seepage in the tunnel. The rebuild also added galvanized iron and trenches to try to keep moisture out, along with barbed wire fencing to prevent cattle from entering the tunnel. The western end of the tunnel was extended by 167 feet (51 m) as well at this time.[3]

In October 1935, work began under the Works Progress Administration to bore out the tunnel; when completed on June 30, 1937 at a cost of US$358,664 (equivalent to $7,602,000 in 2023), the height was extended to 17 feet (5.2 m) and the width was extended to 20 feet (6.1 m). Workers lined the tunnel with 12 inches (300 mm) of unreinforced concrete. During the widening work, a 50-foot (15 m) long section of the tunnel caved in at the western end of the tunnel on May 31, 1936. The tunnel had been lined with concrete for a length of 1,785 feet (544 m), but the cave-in occurred in the part of the tunnel that was still relying on timber supports. Work on the tunnel did not resume until August 1936.[3] As modified in 1937, the tunnel was still narrower at the western extension completed in 1925, retaining the original width of 16 feet (4.9 m).[3]

Caltrans extended the eastern portion of the tunnel by 50 feet (15 m) when the Bayshore Freeway was rebuilt in 1953.[3]

The reconstruction in 2017 cost an estimated $7 million, and involved the injection of 45,000 pounds (20,000 kg) of polyurethane resin to stop leaks along with 900 short tons (820 t) of new paving. Electricity consumption was reduced by 40% with the switch to LED lighting.[9] Prior to the 2017 work, stalactites formed from the water seeping through the rock and concrete, which were removed and displayed at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. The amount of water leaking through the cracks led some to nickname certain areas of the tunnel "the car wash."[4]

Traffic notes[edit]

Automotive traffic through the tunnel is controlled by traffic lights at each end of the tunnel, which allows one-way traffic for five minutes at a time. The single reversible lane for cars is flanked by two bicycle lanes on either side.[10] The five-minute wait is billed as "the longest stoplight in America."[12] Bunker Road itself is named for Col. Paul Bunker, who died in a Japanese prison camp in 1943.[3][12]

References[edit]

- ^ Lile, Thomas (2 April 1973). Forts Baker, Barry and Cronkhite (Report). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Koval, Ana B. (July 1993). Forts Baker-Barry Tunnel, HAER No. CA-139 (PDF) (Report). Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d Prado, Mark (9 March 2017). "Marin Headlands' 'Five-Minute Tunnel' gets rehab work". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Harbor Defenses of San Francisco Notes" (PDF). The Coastal Artillery Journal. 80 (3): 264. May–June 1937. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

The tunnel connecting Fort Baker and Fort Barry, on which work has been in progress for over a year for the purpose of widening, will be completed in June. More than $100,000 have been expended in enlarging this tunnel which has now a width of 20 feet and a length of one-half mile.

- ^ "Preliminary Tunnel Inspection". (Microsoft Excel) Federal Highway Administration. 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Marin County Highways". AA Roads. 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Prado, Mark (22 November 2016). "Tunnel near Sausalito to be closed for four months to start 2017". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ a b Prado, Mark (2 June 2017). "Marin Headlands' "Five-Minute Tunnel" reopens Saturday". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ a b Cabanatuan, Michael (27 November 2016). "Marin Headlands' 1-lane tunnel faces long shutdown". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Erwin N. (November 1979). Historic Resource Study D-1506: Forts Baker, Barry, Cronkhite of Golden Gate National Recreation Area, California (PDF) (Report). National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. pp. 54–57. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ a b Whiting, Sam (3 October 2004). "Peace and Quiet / Bunking down at Fort Barry is a park employee perk". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

External links[edit]

- Historic American Engineering Record (1993). "Forts Baker-Barry Tunnel, Under Lime Point Ridge on Bunker Road, Sausalito, Marin County, CA". Library of Congress. Retrieved 7 April 2018.