User:Millertime/Books/WWII/Course of the War

War breaks out in Europe[edit]

On 1 September 1939, Germany and Slovakia—a client state in 1939—attacked Poland. On 3 September 1939 after Germany failed to withdraw in accordance with French and British demands, France and Britain, followed by the countries of the Commonwealth, declared war on Germany but provided little military support to Poland other than a small French attack into the Saarland.[1] On 17 September 1939, after signing an armistice with Japan, the Soviets launched their own invasion of Poland.[2] By early October, Poland was divided among Germany, the Soviet Union, Lithuania and Slovakia, although Poland never officially surrendered and continued the fight outside its borders.[3]

Following the invasion of Poland and a German-Soviet treaty governing Lithuania, the Soviet Union forced the Baltic countries to allow it to station Soviet troops in their countries under pacts of "mutual assistance."[4][5][6] Finland rejected territorial demands and was invaded by the Soviet Union in November 1939.[7] The resulting conflict ended in March 1940 with Finnish concessions.[8] France and the United Kingdom, treating the Soviet attack on Finland as tantamount to entering the war on the side of the Germans, responded to the Soviet invasion by supporting the USSR's expulsion from the League of Nations.[6] In June 1940, the Soviet Armed Forces invaded and occupied the neutral Baltic States.[5]

In Western Europe, British troops deployed to the Continent, but in a phase nicknamed the Phoney War by the British and "Sitzkrieg" (sitting war) by the Germans, neither side launched major operations against the other until April 1940.[9] The Soviet Union and Germany entered a trade pact in February of 1940, pursuant to which the Soviets received German military and industrial equipment in exchange for supplying raw materials to Germany to help circumvent a British blockade.[10]

In April 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway to secure shipments of iron ore from Sweden, which the Allies would try to disrupt.[11] Denmark immediately capitulated, and despite Allied support, Norway was conquered within two months.[12] British discontent over the Norwegian campaign led to the replacement of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain by Winston Churchill on 10 May 1940.[13]

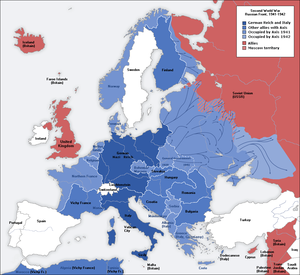

Axis advances[edit]

On that same day, Germany invaded France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.[14] The Netherlands and Belgium were overrun using blitzkrieg tactics in a few days and weeks, respectively.[15] The French fortified Maginot Line was circumvented by a flanking movement through the thickly wooded Ardennes region,[14] mistakenly perceived by French planners as an impenetrable natural barrier against armoured vehicles.[16] British troops were forced to evacuate the continent at Dunkirk, abandoning their heavy equipment by the end of the month. On 10 June, Italy invaded, declaring war on both France and the United Kingdom;[17] twelve days later France surrendered and was soon divided into German and Italian occupation zones,[18] and an unoccupied rump state under the Vichy Regime. On 14 July, the British attacked the French fleet in Algeria to prevent its possible seizure by Germany.[19]

With France neutralised, Germany began an air superiority campaign over Britain (the Battle of Britain) to prepare for an invasion.[20] The campaign failed, and the invasion plans were cancelled by September. Using newly captured French ports, the German Navy enjoyed success against an over-extended Royal Navy, using U-boats against British shipping in the Atlantic. Italy began operations in the Mediterranean, initiating a siege of Malta in June, conquering British Somaliland in August, and making an incursion into British-held Egypt in September 1940.[21]

Throughout this period, the neutral United States took measures to assist the Western Allies. In November 1939, the American Neutrality Act was amended to allow 'Cash and carry' purchases by the Allies.[22] In 1940, following the German capture of Paris, the size of the United States Navy was significantly increased[23] In September, the United States further agreed to a trade of American destroyers for British bases.[24] Still, a large majority of the American public continued to oppose any direct military intervention into the conflict well into 1941.[25]

At the end of September 1940, the Tripartite Pact united Japan, Italy, and Germany to formalize the Axis Powers.[26] The Tripartite Pact stipulated that any country, with the exception of the Soviet Union, not in the war which attacked any Axis Power would be forced to go to war against all three.[27] During this time, the United States continued to support the United Kingdom by introducing the Lend-Lease policy authorizing the provision of war materiel and other items[28] and creating a security zone spanning roughly half of the Atlantic Ocean where the United States Navy protected British convoys.[29] As a result, Germany and the United States found themselves engaged in sustained naval warfare in the North and Central Atlantic by October 1941, even though the United States remained officially neutral.[30][31]

The Axis expanded in November 1940 when Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania joined the Tripartite Pact.[32] These countries participated in the subsequent invasion of the USSR, with Romania making the largest contribution to recapture territory ceded to the USSR and pursue its leader Ion Antonescu's desire to combat communism.[33] In October 1940, Italy invaded Greece but within days was repulsed and pushed back into Albania, where a stalemate soon occurred.[34] In December 1940, British Commonwealth forces began counter-offensives against Italian forces in Egypt and Italian East Africa.[35] By early 1941, with Italian forces having been pushed back into Libya by the Commonwealth, Churchill ordered a dispatch of troops from Africa to bolster the Greeks.[36] The Italian Navy also suffered significant defeats, with the Royal Navy putting three Italian battleships out of commission by carrier attack at Taranto, and neutralising several more warships at Cape Matapan.[37]

The Germans soon intervened to assist Italy. Hitler sent German forces to Libya in February, and by the end of March they had launched an offensive against the diminished Commonwealth forces.[38] In under a month, Commonwealth forces were pushed back into Egypt with the exception of the besieged port of Tobruk.[39] The Commonwealth attempted to dislodge Axis forces in May and again in June, but failed on both occasions.[40] In early April, following Bulgaria's signing of the Tripartite Pact, the Germans intervened in the Balkans by invading Greece and Yugoslavia following a coup; here too they made rapid progress, eventually forcing the Allies to evacuate after Germany conquered the Greek island of Crete by the end of May.[41]

The Allies did have some successes during this time. In the Middle East, Commonwealth forces first quashed a coup in Iraq which had been supported by German aircraft from bases within Vichy-controlled Syria,[42] then, with the assistance of the Free French, invaded Syria and Lebanon to prevent further such occurrences.[43] In the Atlantic, the British scored a much-needed public morale boost by sinking the German flagship Bismarck.[44] Perhaps most importantly, during the Battle of Britain the Royal Air Force had successfully resisted the Luftwaffe's assault, and on 11 May 1941, Hitler called off the bombing campaign.[45]

The war becomes global[edit]

On 22 June 1941, Germany, along with other European Axis members and Finland, invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. The primary targets of this surprise offensive[46] were the Baltic region, Moscow, and Ukraine, with an ultimate goal of ending the 1941 campaign near the Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan line, connecting the Caspian and White Seas. Hitler's objectives were to eliminate the Soviet Union as a military power, exterminate Communism, generate Lebensraum ("living space")[47] by dispossessing the native population[48] and guarantee access to the strategic resources needed to defeat Germany's remaining rivals.[49]

Although the Red Army was preparing for strategic counter-offensives before the war,[50] Barbarossa forced the Soviet supreme command to adopt a strategic defence. During the summer, the Axis made significant gains into Soviet territory, inflicting immense losses in both personnel and materiel. By the middle of August, however, the German Army High Command decided to suspend the offensive of a considerably depleted Army Group Centre, and to divert the Second Panzer Group to reinforce troops advancing toward central Ukraine and Leningrad.[51] The Kiev offensive was overwhelmingly successful, resulting in encirclement and elimination of four Soviet armies, and made further advance into Crimea and industrially developed Eastern Ukraine (the First Battle of Kharkov) possible.[52]

The diversion of three quarters of the Axis troops and the majority of their air forces from France and the central Mediterranean to the Eastern Front[53][54] prompted the United Kingdom to reconsider its grand strategy.[55] In July, the UK and the Soviet Union formed a military alliance against Germany[56] and jointly invaded Iran shortly afterwards to secure the Persian Corridor and Iran's oilfields.[57] In August, the United Kingdom and the United States jointly issued the Atlantic Charter.[58]

By October, when Axis operational objectives in Ukraine and the Baltic region were achieved, with only the sieges of Leningrad[59] and Sevastopol continuing,[60] a major offensive against Moscow had been renewed. After two months of fierce battles, the German army almost reached the outer suburbs of Moscow, where the exhausted troops[61] were forced to suspend their offensive.[62] Large territorial gains were made by Axis forces, but their campaign had failed to achieve its main objectives: two key cities remained in Soviet hands, the Soviet capability to resist was not broken, and the Soviet Union retained a considerable part of its military potential. The blitzkrieg phase of the war in Europe had ended.[63]

By early December, freshly mobilised reserves[64] allowed the Soviets to achieve numerical parity with Axis troops.[65] This, as well as intelligence data that established a minimal number of Soviet troops in the East sufficient to prevent any attack by the Japanese Kwantung Army,[66] allowed the Soviets to begin a massive counter-offensive that started on 5 December along a 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) front and pushed German troops 100–250 kilometres (62–155 mi) west.[67]

On 7 December (8 December in Asian time zones), 1941, Japan attacked British and American holdings with near-simultaneous offensives against Southeast Asia and the Central Pacific.[68] These included an attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, landings in Thailand and Malaya[68] and the battle of Hong Kong.

These attacks prompted the United States, United Kingdom, Australia,[69] other Western Allies,[70] and China (already fighting the Second Sino-Japanese War), to formally declare war on Japan. Germany and the other members of the Tripartite Pact responded by declaring war on the United States. In January, the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, China, and 22 smaller or exiled governments issued the Declaration by United Nations, which affirmed the Atlantic Charter.[71] The Soviet Union did not adhere to the declaration; it maintained a neutrality agreement with Japan,[72][73] and exempted itself from the principle of self-determination.[58]

Germany, now officially at war with the United States, increased its naval operations in the Atlantic. Exploiting dubious American naval command decisions, the German navy ravaged Allied shipping off the American Atlantic coast.[74] Despite considerable losses, European Axis members stopped a major Soviet offensive in Central and Southern Russia, keeping most territorial gains they achieved during the previous year.[75] In North Africa, the Germans launched an offensive in January, pushing the British back to positions at the Gazala Line by early February,[76] followed by a temporary lull in combat which Germany used to prepare for their upcoming offensives.[77]

Axis advance stalls[edit]

On Germany's eastern front, the Axis defeated Soviet offensives in the Kerch Peninsula and at Kharkov[78] and then launched their main summer offensive against southern Russia in June 1942, to seize the oilfields of the Caucasus and occupy Kuban steppe, while maintaining positions on the northern and central areas of the front. The Germans split the Army Group South into two groups: Army Group A struck lower Don River while Army Group B struck south-east to the Caucasus, towards Volga River.[79] The Soviets decided to make their stand at Stalingrad, which was in the path of the advancing German armies.

By mid-November the Germans had nearly taken Stalingrad in bitter street fighting when the Soviets began their second winter counter-offensive, starting with an encirclement of German forces at Stalingrad[80] and an assault on the Rzhev salient near Moscow, though the latter failed disastrously.[81] By early February 1943, the German Army had taken tremendous losses; German troops at Stalingrad had been forced to surrender[82] and the front-line had been pushed back beyond its position before the summer offensive. In mid-February, after the Soviet push had tapered off, the Germans launched another attack on Kharkov, creating a salient in their front line around the Russian city of Kursk.[83]

By November 1941, Commonwealth forces had launched a counter-offensive, Operation Crusader, in North Africa, and reclaimed all the gains the Germans and Italians had made.[84] In the West, concerns the Japanese might utilize bases in Vichy-held Madagascar caused the British to invade the island in early May 1942.[85] This success was offset soon after by an Axis offensive in Libya which pushed the Allies back into Egypt until Axis forces were stopped at El Alamein.[86] On the Continent, raids of Allied commandos on strategic targets, culminating in the disastrous Dieppe Raid,[87] demonstrated the Western Allies' inability to launch an invasion of continental Europe without much better preparation, equipment, and operational security.[88]

In August 1942, the Allies succeeded in repelling a second attack against El Alamein and, at a high cost, managed to deliver desperately needed supplies to the besieged Malta.[89] A few months later, the Allies commenced an attack of their own in Egypt, dislodging the Axis forces and beginning a drive west across Libya.[90] This attack was followed up shortly after by an Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa, which resulted in the region joining the Allies.[91] Hitler responded to the French colony's defection by ordering the occupation of Vichy France;[91] although Vichy forces did not resist this violation of the armistice, they managed to scuttle their fleet to prevent its capture by German forces.[92] The now pincered Axis forces in Africa withdrew into Tunisia, which was conquered by the Allies in May 1943.[93]

Allies gain momentum[edit]

In the Soviet Union, both the Germans and the Soviets spent the spring and early summer of 1943 making preparations for large offensives in Central Russia. On 4 July 1943, Germany attacked Soviet forces around the Kursk Bulge. Within a week, German forces had exhausted themselves against the Soviets' deeply echeloned and well-constructed defences[94][95] and, for the first time in the war, Hitler cancelled the operation before it had achieved tactical or operational success.[96] This decision was partially affected by the Western Allies' invasion of Sicily launched on 9 July which, combined with previous Italian failures, resulted in the ousting and arrest of Mussolini later that month.[97]

On 12 July 1943, the Soviets launched their own counter-offensives, thereby dispelling any hopes of the German Army for victory or even stalemate in the east. The Soviet victory at Kursk heralded the downfall of German superiority,[98] giving the Soviet Union the initiative on the Eastern Front.[99][100] The Germans attempted to stabilise their eastern front along the hastily fortified Panther-Wotan line, however, the Soviets broke through it at Smolensk and by the Lower Dnieper Offensives.[101]

In early September 1943, the Western Allies invaded the Italian mainland, following an Italian armistice with the Allies.[102] Germany responded by disarming Italian forces, seizing military control of Italian areas,[103] and creating a series of defensive lines.[104] German special forces then rescued Mussolini, who then soon established a new client state in German occupied Italy named the Italian Social Republic.[105] The Western Allies fought through several lines until reaching the main German defensive line in mid-November.[106]

German operations in the Atlantic also suffered. By May 1943, as Allied counter-measures became increasingly effective, the resulting sizable German submarine losses forced a temporary halt of the German Atlantic naval campaign.[107] In November 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met with Chiang Kai-shek in Cairo[108] and then with Joseph Stalin in Tehran.[109] The former conference determined the post-war return of Japanese territory,[108] while the latter included agreement that the Western Allies would invade Europe in 1944 and that the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan within three months of Germany's defeat.[109]

In January 1944, the Allies launched a series of attacks in Italy against the line at Monte Cassino and attempted to outflank it with landings at Anzio.[110] By the end of January, a major Soviet offensive expelled German forces from the Leningrad region,[111] ending the longest and most lethal siege in history. The following Soviet offensive was halted on the pre-war Estonian border by the German Army Group North aided by Estonians hoping to re-establish national independence. This delay slowed subsequent Soviet operations in the Baltic Sea region.[112] By late May 1944, the Soviets had liberated Crimea, largely expelled Axis forces from Ukraine, and made incursions into Romania, which were repulsed by the Axis troops.[113] The Allied offensives in Italy had succeeded and, at the expense of allowing several German divisions to retreat, on 4 June Rome was captured.[114]

Allies close in[edit]

On 6 June 1944 (known as D-Day), the Western Allies invaded northern France and, after reassigning several Allied divisions from Italy, southern France.[115] These landings were successful, and led to the defeat of the German Army units in France. Paris was liberated by the local resistance assisted by the Free French forces on 25 August[116] and the Western Allies continued to push back German forces in Western Europe during the latter part of the year. An attempt to advance into northern Germany spear-headed by a major airborne operation in the Netherlands ended with a failure.[117] The Allies also continued their advance in Italy until they ran into the last major German defensive line.

On 22 June, the Soviets launched a strategic offensive in Belarus (known as "Operation Bagration") that resulted in the almost complete destruction of the German Army Group Centre.[118] Soon after that, another Soviet strategic offensive forced German troops from Western Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The successful advance of Soviet troops prompted resistance forces in Poland to initiate several uprisings, though the largest of these, in Warsaw, as well as a Slovak Uprising in the south, were not assisted by the Soviets and were put down by German forces.[119] The Red Army's strategic offensive in eastern Romania cut off and destroyed the considerable German troops there and triggered a successful coup d'état in Romania and in Bulgaria, followed by those countries' shift to the Allied side.[120]

In September 1944, Soviet Red Army troops advanced into Yugoslavia and forced the rapid withdrawal of the German Army Groups E and F in Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia to rescue them from being cut off.[121] By this point, Communist-led partisans under Marshal Josip Broz Tito controlled much of the territory of Yugoslavia and were engaged in delaying efforts against the German forces further south. In northern Serbia, the Red Army, with limited support from Bulgarian forces, assisted the partisans in a joint liberation of the capital city of Belgrade on 20 October. A few days later, the Soviets launched a massive assault against German-occupied Hungary that lasted until the fall of Budapest in February 1945.[122] In contrast with impressive Soviet victories in the Balkans, the bitter Finnish resistance to the Soviet offensive in the Karelian Isthmus denied the Soviets occupation of Finland and led to the signing of Soviet-Finnish armistice on relatively mild conditions,[123][124] with a subsequent shift to the Allied side by Finland.

Axis collapse, Allied victory[edit]

On 16 December 1944, Germany attempted its last desperate measure for success on the Western Front by marshalling German reserves to launch a massive counter-offensive in the Ardennes to attempt to split the Western Allies, encircle large portions of Western Allied troops and capture their primary supply port at Antwerp in order to prompt a political settlement.[125] By January, the offensive had been repulsed with no strategic objectives fulfilled.[125] In Italy, the Western Allies remained stalemated at the German defensive line. In mid-January 1945, the Soviets attacked in Poland, pushing from the Vistula to the Oder river in Germany, and overran East Prussia.[126] On 4 February, U.S., British, and Soviet leaders met in Yalta. They agreed on the occupation of post-war Germany,[127] and when the Soviet Union would join the war against Japan.[128]

In February, the Soviets invaded Silesia and Pomerania, while Western Allied forces entered Western Germany and closed to the Rhine river. In March, the Western Allies crossed the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr, encircling a large number of German troops,[129] while the Soviets advanced to Vienna. In early April, the Western Allies finally pushed forward in Italy and swept across Western Germany, while Soviet forces stormed Berlin in late April; the two forces linked up on Elbe river on 25 April. On 30 April 1945, the Reichstag was captured, signalling the military defeat of Third Reich.[130]

Several changes in leadership occurred during this period. On 12 April, U.S. President Roosevelt died and was succeeded by Harry Truman. Benito Mussolini was killed by Italian partisans on 28 April.[131] Two days later, Hitler committed suicide, and was succeeded by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz.[132]

German forces surrendered in Italy on 29 April and in Western Europe on 7 May.[133] On the Eastern Front, Germany surrendered to the Soviets on 8 May. A German Army Group Centre resisted in Prague until 11 May.[134]

Notes[edit]

- ^ May, Ernest R (2000). Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France (Google books). I.B.Tauris. p. 93. ISBN 1850433291. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Zaloga, Steven J.; Gerrard, Howard (2002). Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg (Google books). Osprey Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 1841764086. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Hempel, Andrew (2003). Poland in World War II: An Illustrated Military History (Google books). Hippocrene Books. p. 24. ISBN 078181004. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Smith, David J. (2002). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (Google books). Routledge. 1st edition. p. 24. ISBN 0415285801. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999). Endgame in NATO's Enlargement: The Baltic States and Ukraine (Google books). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 0275963632. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b Murray & Millett 2001, p. 55–56

- ^ Spring, D. W (April 1986). "The Soviet Decision for War against Finland, 30 November 1939". Europe-Asia Studies. 38 (2): 207–226. JSTOR 151203. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Hanhimäki, Jussi M (1997). Containing Coexistence: America, Russia, and the "Finnish Solution (Google books). Kent State University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0873385586. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 95 & 121

- ^ Shirer, William L (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. pp. 668–9. ISBN 0671728687.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2001, p. 57–63

- ^ Commager, Henry Steele (2004). The Story of the Second World War (Google books). Brassey's. p. 9. ISBN 1574887416. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Reynolds, David (27 April 2006). From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the International History of the 1940s (Google books). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 76. ISBN 0199284113. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b Crawford, Keith; Foster, Stuart J (2007). War, nation, memory: international perspectives on World War II in school history textbooks (Google books). Information Age Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1593118525. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Shirer, William L (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. pp. 721–3. ISBN 0671728687.

- ^ Regan, Geoffrey (2000). The Brassey's book of military blunders. Brassey's. p. 152. ISBN 157488252X.

- ^ Kennedy, David M (1999). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (Questia books). Oxford University Press. p. 439. ISBN 0195038347. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Klaus, Autbert (2001). Germany and the Second World War Volume 2: Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 311. ISBN 0198228880. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

{{cite book}}: Text "Google books" ignored (help) - ^ Brown, David (2004). The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. Taylor & Francis. p. xxx. ISBN 0714654612.

- ^ Kelly, Nigel; Rees, Rosemary; Shuter, Jane (1998). Twentieth Century World. Heinemann. p. 38. ISBN 0435309838.

- ^ Goldstein, Margaret J (2004). World War II. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 35. ISBN 0822501392.

- ^ Brown, Robert J. (2004). Manipulating the Ether: The Power of Broadcast Radio in Thirties America. McFarland. p. 91. ISBN 0786420669.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (2002). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. University of Illinois Press. p. 60. ISBN 0252070658.

- ^ Maingot, Anthony P. (1994). The United States and the Caribbean: Challenges of an Asymmetrical Relationship. Westview Press. p. 52. ISBN 0813322413.

- ^ Cantril, Hadley (September 1940). "America Faces the War: A Study in Public Opinion". The Public Opinion Quarterly. 4 (3): 390.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 182

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. p. 179. ISBN 9780765618214.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2001, p. 165

- ^ Knell, Hermann (2003). To Destroy a City: Strategic Bombing and Its Human Consequences in World War II. Da Capo. p. 205. ISBN 0306811693.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2001, p. 233–245

- ^ Schoenherr, Steven (1 October 2005). "Undeclared Naval War in the Atlantic 1941". History Department at the University of San Diego. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ^ Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D, eds. (2002). "Tripartite Pact". Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 877. ISBN 0198604467.

- ^ Deletant, Dennis (2002). "Romania". In Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D (eds.). Oxford Companion to World War II. pp. 745–46. ISBN 0198604467.

- ^ Clogg, Richard (1992). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0521808723.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S; Andrew, Stephen (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45 (2): Africa 1940–43. Osprey Publishing. pp. 9–10. ISBN 1855328658.

- ^ Brown, David (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean. Routledge. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0714652059.

- ^ Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 1852854170.

- ^ Laurier, Jim (2001). Tobruk 1941: Rommel's opening move. Osprey Publishing. pp. 7–8. ISBN 1841760927.

- ^ Murray & Millett 2001, p. 263–67

- ^ Macksey, Kenneth (1997). Rommel: battles and campaigns. Da Capo Press. pp. 61–63. ISBN 0306807866.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 229

- ^ Watson, William E (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 80. ISBN 0275974707.

- ^ Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 154. ISBN 1852854170.

- ^ Stewart, Vance (2002). Three Against One: Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin Vs Adolph Hitler. Sunstone Press. p. 159. ISBN 0865343772.

- ^ "The London Blitz, 1940". Eyewitness to History. Ibis Communications. 2001. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ Sella, Amnon (July 1978). ""Barbarossa": Surprise Attack and Communication". Journal of Contemporary History. 13 (3): 555–83. doi:10.1177/002200947801300308. S2CID 220880174.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (2007). Fateful Choices. Allen Lane. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-0713997125.

- ^ Steinberg, Jonathan (June 1995). "The Third Reich Reflected: German Civil Administration in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941–4". The English Historical Review. 110 (437): 620–51. doi:10.1093/ehr/CX.437.620.

- ^ Hauner, Milan (January 1978). "Did Hitler Want a World Dominion?". Journal of Contemporary History. 13 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1177/002200947801300102. S2CID 154865385.

- ^ Roberts, Cynthia A (December 1995). "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–26. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322.

- ^ Wilt, Alan F. (December 1981). "Hitler's Late Summer Pause in 1941". Military Affairs. 45 (4): 187–91. doi:10.2307/1987464. JSTOR 1987464.

- ^ Erickson, John (2003). The Road to Stalingrad. Cassell Military. pp. 114–137. ISBN 0304365416.

- ^ Glantz 2001, p. 9

- ^ "Hitler Can Be Beaten". New York Times. 5 August 1941. pp. C18. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ^ Farrell, Brian P (October 1993). "Yes, Prime Minister: Barbarossa, Whipcord, and the Basis of British Grand Strategy, Autumn 1941". The Journal of Military History. 57 (4): 599–625. doi:10.2307/2944096. JSTOR 2944096.

- ^ Pravda, Alex; Duncan, Peter J. S (1990). Soviet-British Relations Since the 1970s. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0521374944.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D (2005). The Logic of Political Survival. MIT Press. p. 425. ISBN 0262524406.

- ^ a b Louis, William Roger (1998). More Adventures with Britannia: Personalities, Politics and Culture in Britain. University of Texas Press. p. 223. ISBN 029274708X.

- ^ Kleinfeld, Gerald R (October 1983). "Hitler's Strike for Tikhvin". Military Affairs. 47 (3): 122–28. doi:10.2307/1988082. JSTOR 1988082.

- ^ Shukman, Harold (2001). Stalin's Generals. Phoenix Press. p. 113. ISBN 1842125133.

- ^ Glantz 2001, p. 26, "By 1 November [the Wehrmacht] had lost fully 20% of its committed strength (686,000 men), up to 2/3 of its ½-million motor vehicles, and 65 percent of its tanks. The German Army High Command (OKH) rated its 136 divisions as equivalent to 83 full-strength divisions."

- ^ Reinhardt, Klaus; Keenan, Karl B (1992). Moscow-The Turning Point: The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in the Winter of 1941–42. Berg. p. 227. ISBN 0854966951.

- ^ Milward, A.S. (1964). "The End of the Blitzkrieg". The Economic History Review. 16 (3): 499–518. JSTOR 2592851.

- ^ Rotundo, Louis (January 1986). "The Creation of Soviet Reserves and the 1941 Campaign". Military Affairs. 50 (1): 21–8. doi:10.2307/1988530. JSTOR 1988530.

- ^ Glantz 2001, p. 26

- ^ Garthoff, Raymond L (October 1969). "The Soviet Manchurian Campaign, August 1945". Military Affairs. 33 (2): 312. doi:10.2307/1983926. JSTOR 1983926.

- ^ Welch, David (1999). Modern European History, 1871–2000: A Documentary Reader. Routledge. p. 102. ISBN 041521582X.

- ^ a b Wohlstetter, Roberta (1962). Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Stanford University Press. pp. 341–43. ISBN 080470598.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

AUSTRALIA DECLARES WAR ON JAPANwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ibibliowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mingst, Karen A.; Karns, Margaret P (2007). United Nations in the Twenty-First Century. Westview Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0813343464.

- ^ Dunn, Dennis J (1998). Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 157. ISBN 0813120233.

- ^ According to Ernest May (May, Ernest (1955). "The United States, the Soviet Union and the Far Eastern War". The Pacific Historical Review. 24 (2): 156. doi:10.2307/3634575. JSTOR 3634575.) Churchill stated: "Russian declaration of war on Japan would be greatly to our advantage, provided, but only provided, that Russians are confident that will not impair their Western Front".

- ^ Gooch, John (1990). Decisive Campaigns of the Second World War. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 0714633690.

- ^ Glantz 2001, p. 31

- ^ Molinari, Andrea (2007). Desert Raiders: Axis and Allied Special Forces 1940–43. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1846030062.

- ^ Mitcham, Samuel W.; Mitcham, Samuel W. Jr (1982). Rommel's Desert War: The Life and Death of the Afrika Korps. Stein & Day. p. 31. ISBN 9780811734134.

- ^ Read, Anthony (2004). The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 764. ISBN 0393048004.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Macmillan. p. 100. ISBN 0333692853.

- ^ Badsey, Stephen (2000). The Hutchinson Atlas of World War II Battle Plans: Before and After. Taylor & Francis. pp. 235–36. ISBN 1579582656.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2003). World War Two: A Military History. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 0415305349.

- ^ Gilbert, Sir Martin (2004). The Second World War: A Complete History. Macmillan. pp. 397–400. ISBN 0805076239.

- ^ Shukman, Harold (2001). Stalin's Generals. Phoenix Press. p. 142. ISBN 1842125133.

- ^ Gannon, James (2002). Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth Century. Brassey's. p. 76. ISBN 1574884735.

- ^ Paxton, Robert O (1972). Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944. Knopf. p. 313. ISBN 0394473604.

- ^ Rich, Norman (1992). Hitler's War Aims: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion. Norton. p. 178. ISBN 0393008029.

- ^ Penrose, Jane (2004). The D-Day Companion. Osprey Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 1841767794.

- ^ Neillands, Robin (2005). The Dieppe Raid: The Story of the Disastrous 1942 Expedition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253347815.

- ^ Thomas, David Arthur (1988). A Companion to the Royal Navy. Harrap. p. 265. ISBN 0245545727.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel; Andrew, Stephen (1998). German Army 1939–1945 (2): North Africa & Balkans. Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 185532640X.

- ^ a b Ross, Steven T (1997). American War Plans, 1941–1945: The Test of Battle. Frank Cass & Co. p. 38. ISBN 0714646342.

- ^ Bonner, Kit; Bonner, Carolyn (2001). Warship Boneyards. MBI Publishing Company. p. 24. ISBN 0760308705.

- ^ Collier, Paul (2003). The Second World War (4): The Mediterranean 1940–1945. Osprey Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 1841765392.

- ^ Glantz, David M. (September 1986). "Soviet Defensive Tactics at Kursk, July 1943". CSI Report No. 11. Combined Arms Research Library. OCLC 278029256. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ^ Glantz, David M (1989). Soviet military deception in the Second World War. Routledge. pp. 149–59. ISBN 9780714633473.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 592. ISBN 0393322521.

- ^ O'Reilly, Charles T (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943–1945. Lexington Books. p. 32. ISBN 0739101951.

- ^ Bellamy, Chris T (2007). Absolute war: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. BAlfred A. Knopf. p. 595. ISBN 978-0375410864.

- ^ O'Reilly, Charles T (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943–1945. Lexington Books. p. 35. ISBN 0739101951.

- ^ Healy, Mark (1992). Kursk 1943: The tide turns in the East. Osprey Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 1855322110.

- ^ Glantz 2001

- ^ McGowen, Tom (2002). Assault From The Sea: Amphibious Invasions in the Twentieth Century. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0761318119.

- ^ Lamb, Richard (1996). War in Italy, 1943–1945: A Brutal Story. Da Capo Press. pp. 154–55. ISBN 0306806886.

- ^ Hart, Stephen; Hart, Russell; Hughes, Matthew (2000). The German Soldier in World War II. MBI Publishing Company. p. 151. ISBN 0760308462.

- ^ Blinkhorn, Martin (1984). Mussolini and Fascist Italy. Methuen & Co. p. 52. ISBN 0415102316.

- ^ Read, Anthony; Fisher, David (1992). The Fall of Berlin. Hutchinson. p. 129. ISBN 0091753376.

- ^ Read, Anthony (2004). The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 804. ISBN 0393048004.

- ^ a b Iriye, Akira (1981). Power and culture: the Japanese-American war, 1941–1945. Harvard University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0674695828.

- ^ a b Polley, Martin (2000). A-Z of modern Europe since 1789. Taylor & Francis. p. 148. ISBN 041518598X.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 660–661

- ^ Glantz, David M (2001). The siege of Leningrad, 1941–1944: 900 days of terror. Zenith Imprint. pp. 166–69. ISBN 0760309418.

- ^ Glantz, David M (2002). The Battle for Leningrad: 1941–1944. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700612084.

- ^ Chubarov, Alexander (2001). Russia's Bitter Path to Modernity: A History of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 122. ISBN 0826413501.

- ^ Havighurst, Alfred F (1962). Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century. The University of Chicago Press. p. 344. ISBN 0226319717.

- ^ Weinberg 1995, p. 695

- ^ Badsey, Stephen (1990). Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 0850459214.

- ^ Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D, eds. (2002). "Market-Garden". Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 877. ISBN 0198604467.

- ^ The operation "was the most calamitous defeat of all the German armed forces in World War II" (Zaloga, Steven J (1996). Bagration 1944: The destruction of Army Group Centre. Osprey Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 1855324784.)

- ^ Berend, Ivan T. (1999). Central and Eastern Europe, 1944–1993: Detour from the Periphery to the Periphery. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0521550661.

- ^ "Armistice Negotiations and Soviet Occupation". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

The coup speeded the Red Army's advance, and the Soviet Union later awarded Michael the Order of Victory for his personal courage in overthrowing Antonescu and putting an end to Romania's war against the Allies. Western historians uniformly point out that the Communists played only a supporting role in the coup; postwar Romanian historians, however, ascribe to the Communists the decisive role in Antonescu's overthrow

- ^ Hastings, Max; Paul Henry, Collier (2004). The Second World War: a world in flames. Osprey Publishing. pp. 223–4. ISBN 1841768308.

- ^ Wiest, Andrew A; Barbier, M. K (2002). Strategy and Tactics Infantry Warfare. Zenith Imprint. pp. 65–6. ISBN 0760314012.

- ^ Wiktor, Christian L (1998). Multilateral Treaty Calendar – 1648–1995. Kluwer Law International. p. 426. ISBN 9041105840.

- ^ Newton, Steven H (1995). Retreat from Leningrad : Army Group North, 1944/1945. Atglen, Philadelphia: Schiffer Books. ISBN 0887408060.

- ^ a b Parker, Danny S (2004). Battle of the Bulge: Hitler's Ardennes Offensive, 1944–1945. Da Capo Press. pp. xiii–xiv, 6–8, 68–70 & 329–330. ISBN 0306813912.

- ^ Glantz 2001, p. 85

- ^ Solsten, Eric (1999). Germany: A Country Study. DIANE Publishing. pp. 76–7. ISBN 0788181793.

- ^ United States Dept. of State (1967). The China White Paper, August 1949. Stanford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0804706085.

- ^ Buchanan, Tom (2006). Europe's troubled peace, 1945–2000. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 21. ISBN 0631221638.

- ^ Shepardson, Donald E (January 1998). "The Fall of Berlin and the Rise of a Myth". The Journal of Military History. 62 (1): 135–154. doi:10.2307/120398. JSTOR 120398.

- ^ O'Reilly, Charles T (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943–1945. Lexington Books. p. 244. ISBN 0739101951.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 823

- ^ Donnelly, Mark (1999). Britain in the Second World War. Routledge. p. xiv. ISBN 0415174252.

- ^ Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 34. ISBN 0700608990.