User:Mattheckatight

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user whom this page is about may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Mattheckatight. |

Here's a little article I've been working on!

Auto-Tune is an audio-processing software plug-in that allows musicians to adjust the pitch and frequency of their musical performances. Auto-Tune was invented by Dr. Andy Hildebrand in 1996, and has since become one of the most popular studio plug-ins and software kits in the recording industry [1]. The plug-in is used primarily for vocal modification, but can also be applied to instrumental performances as well. It works by first measuring the artist’s pitch, which it does by recording and analyzing the repeating audio cycles that make up musical notes [2]. The software then interprets and displays these cycles on a computer and allows its users to easily correct or modify their performance’s pitch.

In the mid 2000’s, Auto-Tune became immensely popular as a vocal effect, and at the present day, it has permeated most pop and hip-hop music [3]. However, despite its obvious popularity with listeners, Auto-Tune remains a subject of controversy; Many contend that it cheapens the integrity of the music [4], while others say that it is an innovation [5].

History[edit]

Auto-Tune is marketed by Antares Audio Technologies, a company founded by Andy Hildebrand in 1990 as Jupiter Systems. Hildebrand, a doctor of electrical engineering, spent the first half of his professional career (1967-1989) working with Exxon Production Research and Landmark Graphics as a geophysical researcher, where he used sonic methods to help locate oil. After retiring at the age of 40, Hildebrand began Jupiter Systems [6]. Before Auto-Tune, Jupiter Systems was responsible for the creation of other plug-ins and editing software, including the “Infinity” seamless looper [7]. The idea for the Auto-Tune was first suggested by a friend of Hildebrand’s; as he was at lunch with her and her husband, she explained to Hildebrand, “I wish I could have a box that could make me sing in tune” [8]. While at the time this seemed impossible, Hildebrand soon designed and built that box [9].

Technology[edit]

Auto-Tune relies upon a technology called digital signal processing (DSP) to alter the tuning of a person’s performance [10]. Although DSP was a technique developed specifically for geophysical purposes, Hildebrand applied the technology to audio processing to create Auto-Tune [11]. Hildebrand says that Auto-Tune uses “a special algorithm designed for intonation correction” [12], and through this algorithm, the software can interpret the pitch of the singer’s voice. After this process, its users can then “nudge” notes into the desired pitch using the software’s “Graphical” mode or let the software correct each note to the nearest in-key pitch with “Automatic” mode [13]. Through these two modes, it is possible for artists to perform both major and minor repairs to whatever they are recording.

Development[edit]

When it was introduced as a plug-in in 1997, it became an instant hit in the recording world, and soon was manufactured as a rack mount for live and studio performances known as the ATR-1 [14]. Hildebrand went on to create several other notable system plug-ins, and renamed the company Antares Audio Technologies in the late-nineties [15]. Auto-Tune has since undergone many upgrades and transformations, the most current editions being Auto-Tune 7, Auto-Tune Evo, and an updated hardware system called the Antares Vocal Producer [16]. Aside from these hardware and software versions of the product, Auto-Tune can also be downloaded as the “I am T-Pain” iPhone application.

Auto-Tune in Music[edit]

Early Use[edit]

Immediately following its release, Auto-Tune became widely used by studio engineers as a sort of “trade secret” [17], and remained somewhat unknown to common listeners until 1998 when Cher released the song “Believe”. “Believe” was the first song to apply Auto-Tune as a vocal effect rather than just a doctoring tool, and it caught the attention of producers and listeners alike [18][19]. This effect is generated by adjustment of Auto-Tune’s “Retune” speed. The retune speed is gauged from zero to 400, and it measures the rate at which the software produces the change in pitch [20]; Hildebrand says, “If you set [the retune speed] to 10, that means that the output pitch will get halfway to the target pitch in 10 milliseconds. But if you let that parameter go to zero, it finds the nearest note and changes the output pitch instantaneously” [21]. Setting the speed to zero, as Cher’s producers did, resulted in the “jumpy and automated” [22] tone that was the hallmark of “Believe”. Soon, other artists such as Madonna, Britney Spears, Celine Dion, and many others began to follow in Cher’s footsteps and use Auto-Tune experimentally [23][24].

Growth[edit]

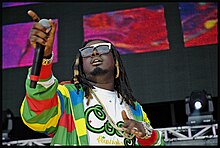

Not until 2003, however, did Auto-Tune begin to grow into the cultural phenomenon it is today. In this year, R&B and rap artist T-Pain, born Fajeem Najm, first experimented with Auto-Tune and realized how he could use the retune speed and other features of the software to create different sounds and add new character to his music [25]. The cheery, robotic nature that Auto-Tune gave to his songs soon became extremely popular in pop and hip-hop music, and he quickly rose from the status of “nobody” into a superstar. From his debut album “Rappa Ternt Sanga” in 2005 till the present day, T-Pain has had 12 singles rank in the Billboard’s Top 10, as well as countless others hits in which he was featured as a guest vocalist [26].

As a result of his influence, other artists began to take an interest in Auto-Tuning as well, including Kanye West, Snoop Dogg, Ludacris, and others [27][28]. Kanye West, for example, collaborated with and learned from T-Pain during the recording of his album “808s and Heartbreak”, which used Auto-Tune for a more “angsty” and heartbroken tone than T-Pain’s music, and many critics considered it “one of the best albums of [2009]” [29]. Because of T-Pain’s reanimation of the “Cher Effect”, the Auto-Tune has grown into a dominating force in contemporary pop, rap, and hip-hop.

Controversy[edit]

Artists[edit]

Despite its well established popularity among listeners, there are still many artists who disapprove of Auto-Tuning. In 2002 country singer Allison Moorer capitalized off of the fact that her album "Miss Fortune" was produced without Auto-Tune. On the back of her album was printed the statement “Pro Tools was not used in the making of this album” [30].

Others, such as rapper and songwriter Jay-Z, criticize Auto-Tune through their music. In 2009, Jay-Z released his single “D.O.A.” or “Death of Auto-Tune”, which attempted to denounce Auto-Tune as a gimmick and draw artists and fans away from its misuse [31]. Ironically, however, Jay-Z himself had experimented and recorded with Auto-Tune, and actually removed his Auto-Tuned tracks from off of his album before its release [32].

In a similar protest, Seattle-based indie rock group Death Cab for Cutie began a cause at the 2009 Grammys in which the band’s members wore light blue ribbons pinned to their suits to “raise awareness of Auto-Tune abuse” [33]. Frontman Ben Gibbard related to reporters, “Over the last 10 years, we've seen a lot of good musicians being affected by this newfound digital manipulation of the human voice, and we feel enough is enough” [34]. Gibbard continued, saying that he wanted to bring back the “Blue note, the note that's not so perfectly in pitch and gives the recording soul and real character. It's how people really sing” [35], and bassist Nick Harmer added the warning that “Otherwise, musicians of tomorrow will never practice. They will never try to be good, because yeah, you can do it just on the computer” [36]. However, despite these frank criticisms of the Auto-Tune, it still remains as powerful and pervasive as ever within popular music.

The Recording Industry[edit]

Auto-Tune, which is generally seen as a studio magic, isn’t even fully respected by many producers. Producer Rick Rubin, for example, says that he prefers to take a “more natural” approach to the recording process, also adding that Auto-Tune tempts artists to not put forward a full effort due to the ease of recording only one take [37].

However, there are still other producers who treat Auto-Tune with great respect, stating that Auto-Tune is incredibly useful in smoothing over small incongruities within individual songs as well as for perfecting already near-perfect songs. Producer Craig Anderson says that Auto-Tune “Gets no respect because when it’s done correctly, you can’t hear that it’s working. If someone uses it tastefully just to correct a few notes here and there, you don’t even know that it’s been used so it doesn’t get any props for doing a good job” [38]. Its proponents also state that performers with fewer means will be able to accomplish more by using Auto-Tune because it cuts down on necessary studio time and allows for fewer takes so that artists don’t need to fret about budgeting [39].

Antares Audio Technologies[edit]

In spite of the mounting opposition to Auto-Tuning, Antares Audio Technologies remains supportive of the technology. When interviewed by Neil DeGrasse Tyson for Nova’s special on Auto-Tune, Hildebrand firmly stated that he sees no wrong in using pitch correction. When questioned on the ethics of correcting a singer’s pitch, Hildebrand suggested “To modify something isn’t necessarily evil. My wife wears makeup. Is that evil?” [40]. Hildebrand also claimed that “If the singer doesn’t have a good tonality to their voice, [the Auto-Tune] isn’t going to make that better” [41]. This thought is seconded by two of Hildebrand’s executes: Antares CEO Stephen Tritto, who said “I can’t even sing well in the shower, and Auto-Tune isn’t going to help me” [42], and Antares Vice President of Marketing Marco Alpert, who relayed “What we always say is a bad singer through Auto-Tune is just a bad singer who’s in tune” [43]. Overall, the Antares company contends that tuning doesn’t necessarily equate with good singing, and “studio magic” won’t cure a bad singer.

While he maintains that to use it for modification isn’t inherently wrong, Hildebrand still admits surprise at the way the Auto-Tune has been used. When asked by Tyson about Cher’s “Believe”, Hildebrand said, “I couldn’t believe it. . . I didn’t think anybody in their right mind would ever use it that way” [44].

This considered, however, Antares Technologies realizes the popularity that this adaptation of his software had amassed and has begun to cater to it. Auto-Tune software has become extremely inexpensive, costing only $79.00, and at the moment there even exists the “I am T-Pain” iPhone application that lets users Auto-Tune their own voice like T-Pain [45]. This extreme availability of Auto-Tune makes it even more prolific within pop music because virtually anyone can own the software and then manipulate their voices.

References[edit]

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ Green 107

- ^ Tyrangiel 1-2

- ^ Sclafani 2

- ^ Chadabe 330

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ Hildebrand, qtd. in Verna 78

- ^ Verna 78

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ Green 107

- ^ “Auto-Tune 1"

- ^ Verna 78

- ^ “Brief History” 1

- ^ “Products”

- ^ Tyrangiel 1

- ^ Verna 78

- ^ Tyrangiel 1

- ^ “Auto-Tune” 1

- ^ Hildebrand, qtd. in Tyrangiel 1

- ^ Tyrangiel 1

- ^ "Auto-Tune" 3

- ^ Tyrangiel 3

- ^ Tyrangiel 2

- ^ Tyrangiel 2

- ^ Reid 1

- ^ "Auto-Tune" 4

- ^ Tyrangiel 2

- ^ Maureen 1

- ^ Reid 1

- ^ West, qtd. in Reid 1

- ^ Gibbard qtd. in Michaels 1

- ^ Michaels 1

- ^ Michaels 1

- ^ Michaels 1

- ^ Rubin, qtd. in Tyrangiel 3

- ^ Anderton, qtd. in Sclafani 2

- ^ Street qtd. in Sclafani

- ^ "Auto-Tune" 3

- ^ "Auto-Tune" 5

- ^ Tritto, qtd. in Verna 78

- ^ Alpert qtd. in Verna 78

- ^ "Auto-Tune" 4

- ^ “Products” 1

Bibliography[edit]

- “Auto-Tune.” Narr. Neil deGrasse Tyson. Nova. PBS, 30 June 2009. Television. 4. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/tech/auto-tune.html

- “A Brief History of Antares.” Antares Technologies. Antares Technologies, 2010. Web. 10 September 2010.2. http://www.antarestech.com/about/history.shtml

- Chadabe, Joel. Electric Sound. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall, 1997. Print.

- Collins, Nick, and Julio d’Escriván, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music. New York: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

- Green, Adam. “Keyboard Reports: Antares Auto-Tune.” Keyboard. Keyboard, July 1997: 107-108. Web. 20 September 2010.

- Massey, Howard. “Editor's Pick: Gettin' Right in Tune: The Antares ATR-1 Auto- Tune Intonation Processor Can Take Any Monophonic Out-of-Tune Signal and Automatically Put It in Tune.” Musician 240. November 1998: 63-65. Web. 8 September 2010.

- Michaels, Sean. “Death Cab for Cutie declare war on Auto-Tune abuse.” Guardian UK. Guardian, 11 Feb. 2009. Web. 21 September 2010.

- “Products.” Antares Technologies. Antares Technologies, 2010. Web. 4 December 2010.http://www.antarestech.com/products/

- Reid, Shaheem. “Jay-Z Premieres New Song, 'D.O.A.': 'Death Of Auto-Tune'.” MTV. MTV, 6 June 2009. Web. 21 September 2010.7. http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1613390/20090606/jay_z.jhtml

- Ryan, Maureen. “What? No pitch correction?.” Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune, 27 April 2003. Web. 14 September 2010.

- Sclafani, Tony. “Oh, my ears! Auto-Tune is ruining music.” Newsvine. Newsvine, 2 June 2009. Web. 14 September 2010.3. http://www.newsvine.com/_news/2009/06/02/2888838-oh-my-ears-auto-tune-is-ruining-music

- Tyrangiel, Josh. “Auto-Tune: Why Pop Music Sounds Perfect.” Time. Time, 5 February 2009. Web. 10 September 2010.http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1877372,00.html

- Verna, Paul. “Pro Audio: Studio Monitor: Recording Pros Tune In to Antares' Novel Processors.” Billboard - The International Newsweekly of Music, Video and Home Entertainment. Billboard, 24 June 2000: 78-79. Web. 8 September 2010.