User:Martinvl/Sandbox2

Dummy[1] Dummy[2][3]Travernor[4]

- 5 May 1789 - Calling of the Estates-General of 1789

- 17 June 1789 - National Assembly

- 20 June 1789 - Tennis Court Oath

- 27 June 1789 - Academy of Sciences appointed a commission (committee - St Andrews, biography of Laplace) to study weights and measures. (Konvitz pg 46)

- 9 July 1789 - Formation of the National Constituent Assembly

- 14 July 1789 - Storming of the Bastille

- 4 August 1789- Nobles surrender right to set weights and measures (Alder pg 88)

- 9 March 1790 - Talleyrand presents report - units based on nature (Hellman p 315), (Alder p90)

- 27 October 1790 - Metric Committee suggested decimal scale for weights, measures and money (Glasser p 71-2)

- 17 March 1791 - Metric committee presents report

- 30 March 1791 - Talleyrand decree

- ??-Apr-1791 French Constituent Assembly set up a committee

- 19 June 1791 - Royal audience (Alder pg 21)

- 21 June 1791 - Flight to Varennes

- 24 June 1791 - Royal seal received (ALder pg 21)

- 1 September 1791 - formation of the Legislative Assembly (France)

- 20 September 1792 - Formation of the National Convention

- 21 January 1793 - Execution of Louis XVI

- April 1793 - Formation of the Committee of Public Safety

- 27 May 1793 -

- 1 August 1793 - Temporary metre

- 8 August 1793 - Supression of Academy

- 5 September 1793 - Start of the Reign of Terror

- 11 September 1793 - Fourcroy ensures that work on weights and measures should continue and the title of "commission temporaire". (Nearly full memebership)

- 28 July 1794 - End of Reign of Terror

- 7 April 1795 - publication of draft metric system

- June 1795 - commission temporaire become "Agence Temporaire des Poids et Mesures"

- 22 August 1795 - National Institute of Sciences and Arts established

- 24 October 1795 - National Institute charged to take on work of agence tempoiraire

- 2 November 1795 - Formation of the French Directory

- 4 April 1796 - Lois 15 Germinal IV - National Institute, which had replaced the academies, charge of all scientific operations pertaining to fixing the units of weights and measures.

- 1796-8 - agence temporaire became "Office for Weights and Measures" under the Minister of the Interior.

- September 1798 - Commission des poids et mesures formed by French Commissioners and foreign deputies from various states friendly to France. Examined results of of Mechelin & Delambre

Glossary[edit]

To avoid verbosity, shortened forms of many names have been used. However the chaotic state of France during the last decade of the eighteenth century has meant that many shortened names have different meanings at different times:

- Academy

- 1666- 1783: Académie des sciences (Academy of Sciences)

- Agency

- Assembly

- 1789: Assemblée nationale (National Assembly)

- 1789 - 1791: Assemblée nationale constituante (Constituent Assembly).

- 1791 - 1792: Legislative Assembly

- Committee

- 1789 - 1790: Committee of the Academy

- 1793 - 1795: Comité de salut public (Committee of Public Safety) (The Government "Cabinet")

- Commission

- Convention

- 1792 - 1795: National Convention (The French "Parliament")

- Institute

18th Century international cooperation[edit]

In the late eighteenth century proposals, similar to those of the seventeenth century for a universal measure, were made for a common international system of measure in the spheres of commerce and technology; when the French Revolutionaries implemented such a system, they drew on many of the seventeenth century proposals.

In the early ninth century, when much of what later became France was part of the Holy Roman Empire, units of measure had been standardised by the Emperor Charlemagne. He had introduced standard units of measure for length and for mass throughout his empire. As the empire disintegrated into separate nations, including France, these standards diverged. It has been estimated that on the eve of the Revolution, a quarter of a million different units of measure were in use in France; in many cases the quantity associated with each unit of measure differed from town to town, and even from trade to trade.[5]: 2–3 Although certain standards, such as the pied du roi (the King's foot) had a degree of pre-eminence and were used by scientists, many traders chose to use their own measuring devices, giving scope for fraud and hindering commerce and industry.[6] These variations were promoted by local vested interests, but hindered trade and taxation.[7][8] In contrast, in England the Magna Carta (1215) had stipulated that "there shall be one unit of measure throughout the realm".[9]

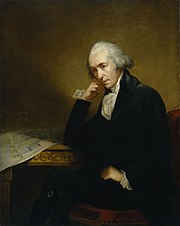

By the mid eighteenth century, it had become apparent that standardisation of weights and measures between nations who traded and exchanged scientific ideas with each other was necessary. Spain, for example, had aligned her units of measure with the royal units of France,[1] and Peter the Great aligned the Russian units of measure with those of England.[11] In 1783 the British inventor James Watt, who was having difficulties in communicating with German scientists, called for the creation of a global decimal measurement system, proposing a system which, like the seventeenth century proposal of Wilkins, used the density of water to link length and mass[10] and in 1788 the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier commissioned a set of nine brass cylinders—a [French] pound and decimal subdivisions thereof for his experimental work.[4]: 71

In 1789 the French finances were in a perilous state, several years of poor harvests had resulted in hunger among the peasants and reforms were thwarted by vested interests.[12] On 5 May 1789 Louis XVI summonsed the Estates-General which has been in abeyance since 1614 triggering a series of events that were to cumulate in the French Revolution. On 20 June 1789 the newly-formed Assemblée nationale (National Assembly) took an oath not to disband until a constitution has been drafted resulting in the setting up, on 27 June 1789, of the Assemblée nationale constituante (Constituent Assembly). On the same day, the Académie des sciences (Academy of Sciences) set up a committee to investigate the reform of weights and measures which, due to their diverse nature, had become a vehicle for corruption.[5]: 2–3 [13]: 46

On 4 August 1789, three weeks after the storming of the Bastille the nobility surrendered their privileges, including the right to control local weights and measures.[5]: 88

Talleyrand, Assembly representative of the clergy, revolutionary leader and former Bishop of Autun, at the prompting of the mathematician and secretary of the Academy Condorcet,[14] approached the British and the Americans in early 1790 with proposals of a joint effort to define a common standard of length based on the length of a pendulum. The United Kingdom, represented by John Riggs Miller and the United States represented by Thomas Jefferson agreed in principal to the proposal, but the choice of latitude for the pendulum proved to be a sticking point: Jefferson opting for 38°N, Talleyrand for 45°N and Riggs-Miller for London's latitude.[5]: 93–95 On 8 May 1790 Talleyrand's proposal in the Assembly that the new measure be defined at 45°N "or whatever latitude might be preferred"[15] won the support of all parties concerned.[7] On 13 July 1790, Jefferson presented a document Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States to the U.S. Congress in which, like Wilkins, he advocated a decimal system in which units that used traditional names such as inches, feet, roods were related to each by the powers of ten. Again, like Wilkins, he proposed a system of weights based around the weight of a cubic unit of water, but unlike Wilkins, he proposed a "rod pendulum" rather than a "bob pendulum".[16] Riggs-Miller promoted Tallyrand's proposal in the British House of Commons.

In response to Tallyrand's proposal of 1790, the Assembly set up a new committee under the auspices of the Academy to investigate weights and measures. The members were five of the most able scientists of the day—Jean-Charles de Borda, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Pierre-Simon Laplace, Gaspard Monge and Condorcet. The committee, having decided that counting and weights and measures should use the same radix, debated the use of the duodecimal system as an alternative the decimal system. Eventually the committee decided that the advantages of divisibility by 3 and 4 was outweighed by the complications of introducing a duodecimal system and on 27 October 1790 recommended to the Assembly that currency, weights and measures should all be based on a decimal system. They also argued in favour of the decimalization of time and of angular measures.[4]: 71–72 The committee examined three possible standards for length - the length of pendulum that beat with a frequency of once a second at 45° latitude, a quarter of the length of the equator and a quarter of the length of a meridian. The committee also proposed that the standard for weight should be the weight of distilled water held in cube with sides a decimal proportion of the standard for length.[2][3][4]: 50–51 The committee's final report to the Assembly on 17 March 1791 recommended the meridional definition for the unit of length.[17][18] inventor of the repeating circle was appointed chairman.[5]: 20–21 The proposal was accepted by the Assembly on 30 March 1791.[15]

Jefferson's report was considered but not adopted by the U.S. Congress and Riggs-Miller lost his UK Parliamentary seat in the election of 1790.[19] When the French later overthrew their monarchy Britain withdrew her support.[5]: 252–253 and France decided to "go it alone".[5]: 88–96

Revolutionary France (1791–1812)[edit]

When the National Assembly accepted the committee's report, the Académie des sciences was instructed to implement the proposals. The academy broke the tasks into five operations, allocating each part to separate working group:[4]: 82

- Measuring the difference in latitude between Dunkirk and Barcelona and triangulate between them. (Cassini, Méchain, and Legendre.

- Measuring the baselines used for the survey. (Monge, Meusnier)

- Verify the length of the second pendulum at 45° latitude. (de Borda and de Coulomb)

- Verify the weight in vacuo of a given volume of distilled water. (Antoine Lavoisier and René Just Haüy)

- Publish conversion tables relating the new units of measure to the existing units of measure. (Tillet)

On 19 June 1791, the day before Louis XVI's flight to Varennes Cassini, Mechain, Legendre and Borda obtained a royal audience where the king agreed to fund both the measurement of the meridian and the remeasurements of made by Cassini's father. The king's authorization arrived on 24 June 1791.[5]: 20–21 In May 1792 Cassini, loyal to Louis XVI but not to the Revolution was replaced by was replaced by Delambre.[20]

Time[edit]

[1] - decimal clocks and angles 1795, not 1793!!!

The grade has never been used extensively, even by the nation that devised it. Konvitz: *Page 46 - 27 June 1789 Academy of Sciences appointed a commission - Lavoisier, Laplace, Brisson, Tillet and le Roy to study weights and measures.

- Page = 51 - Gaspard de Prony, Director of Cadastry prepeared tables in 1794 for the conversion of duodecinal to decimal units

Angular measure (c1793)[edit]

Although there was no specific decree regarding angular measure which was also decimalised during the 1790s, it is reported to have been used in 1794,[13]: 51 but was not mentioned in the metric system decree of 1795.[3] A grade was defined as being 1⁄100 of a quadrant, making 400 grades in a full circle. Fractions of the grade used the standard metric prefixes, thus one centigrade was 1⁄10000 of a quadrant, making one centigrade of longitude approximately one kilometer. The adoption of the grade by the cartographic community was sufficient to warrant a mention in the Lexicographia-neologica Gallica[21] in 1801 and its use continued on military maps through the nineteenth century[22] into the twentieth century.[23] It appears not to have been widely used outside cartography.[24]

Mass[edit]

Refer to Adams for more details

References[edit]

- ^ a b Dummy text

- ^ a b Adams,John Quincy (22 February 1821). Report upon Weights adn Measures. Washinton DC: Office of the Secretary of State of the United States. Cite error: The named reference "Adams" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Dummy

- ^ a b c d e Tavernor, Robert (2007). Smoot's Ear: The Measure of Humanity. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12492-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alder. The Measure of all Things - The Seven-Year-Odyssey that Transformed the World. ISBN 978-0349115078.

- ^ "History of measurement". Métrologie française. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Larousse, Pierre, ed. (1874), "Métrique", Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, vol. 11, Paris: Pierre Larousse, pp. 163–64.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Larousse, Pierre, ed. (1874), "Métrique", Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, vol. 11, Paris: Pierre Larousse, pp. 163–64.

- ^ Nelson, Robert A. (1981), "Foundations of the international system of units (SI)" (PDF), Phys. Teacher: 597.

- ^ "Magna Charta translation". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ a b Carnegie, Andrew (May 1905). James Watt (PDF). Doubleday, Page & Company. pp. 59–60. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ Jackson, Lowis D'Aguilar. Modern metrology; a manual of the metrical units and systems of the present century (1882). London: C Lockwood and co. p. 11. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ Palmer, A W (1962). A Dictionary of Modern History. Penguin Books. French Revolution.

- ^ a b Konvitz, Josef (1987). Cartography in France, 1660-1848: Science, Engineering, and Statecraft. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45094-5.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat Condorcet", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ a b "Lois et décrets" [Laws and decrees]. Histoire de la métrologie (in French). Paris: Association Métrodiff. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (4 July 1790). "Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights, and Measures of the United States; Communicated to the House of Representatives July 13, 1790". New York. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Hellman, C. Doris (January 1936). "Legendre and the French Reform of Weights and Measures". Osiris. 1. University of Chicago Press: 314–340. doi:10.1086/368429. JSTOR 301613. S2CID 144499554.

- ^ Glaser, Anton (1981) [1971]. History of Binary and other Nondecimal Numeration (PDF) (Revised ed.). Tomash. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-938228-00-5. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Riggs-Miller". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64753. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Jean-Dominique Comte de Cassini", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ "grade". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ For example this 1852military map of Paris

- ^ For example this 1902 military map of Paris.

- ^ Cross, Charles R (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) (1873). Course in elementary physics. Boston. p. 17. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)