User:Marissah3220/Climate change in california

Impact of Climate Change (California Water Page)[edit]

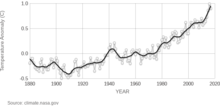

The burning of fossil fuels, which has been occurring at an unprecedented rate since the Industrial Revolution in the 1950's, has increased the concentration of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide and methane, in the atmosphere. In 2018, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations were 407 parts per million (ppm), and the Global Carbon Budget estimated that emissions would continue to grow by 0.6% each decade.[1] Increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have caused Earth's global surface temperatures to increase as well, a phenomenon called climate change. In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that global average temperatures were increasing by 0.2°C each decade and that the climate that year was 1°C above preindustrial levels.[2] The IPCC warns that anthropogenic emissions must decrease to limit climate change and its impacts; In California, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) predicts that sea level rise between 1-4 by 2100, more extreme weather conditions, and changes in precipitation due to climate change will have an impact on the state's water resources.[3] In addition, these impacts will also change the state's water management systems and policies. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, the number of people and the value of property is increasing in flood prone regions of the state, including Sacramento, which means that the economic risk and threat to public safety is increasing[4]. This reality is illustrated by the 2017 Oroville Dam failure where 180,000 were emergency evacuated and nearly $500 million in damages were accrued.

Sea Level Rise[edit]

Although the Earth's oceans have been rising for since the last ice age around 18,000 years ago as a result of melting sea and land ice, climate change is expected to accelerate the rate of global sea level rise. According to California's Fourth Climate Change Assessment, published in 2018, climate change will stimulate 54 inches of sea level rise by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions continued at their current rates.[5] This phenomenon is expected to cause coastal and estuarial flooding which will have both economic, environmental, and political ramifications in terms of water. In fact, scientists at the California Department of Water Resources believe that sea level rise will cause more salt water to intrude the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state's largest estuary, "the heart of the California water supply system and the source of water for 25 million Californians and millions of acres of farmland."[6] Rising sea levels will also present flood hazards from storms and saltwater intrusion to coastal aquifers, according to the department's report.

Extreme Weather Conditions[edit]

Climate change will also cause more extreme weather conditions to occur in the state. In general, California's climate will become dryer and warmer over time.[7] According to the United States Geological Survey, higher atmospheric surface temperatures and warmer ocean waters create fuel for more powerful storms, like hurricanes or monsoons, to develop and can lead to faster wind speeds during storms.[8] This effect will cause more frequent and extreme droughts as well as extreme precipitation events that could cause flooding according to the National Climate Assessment. [9] In fact, these effects are already evident in the state. For instance, the drought of 2012-2016 was the most extreme drought that the state has ever seen, and droughts were the most common disaster source in California in 2016 according to the State of California Hazard Mitigation Plan.[10] In addition, monitoring by the California Department of Water Resources suggests that droughts have become more severe since the Industrial Revolution. In fact, the drought of 2012 to 2016 was the most extreme drought that the state has ever seen.[10] At the same time, floods have also been worsening over time and will continue to become more extreme as atmospheric temperatures continue to increase.

Changes in Precipitation[edit]

Although California has always extreme daily, monthly, and annual variations in rainfall, the state's precipitation patterns have become increasingly more variable over time trending towards a drier climate as a result of global warming[7]. Among all of the effects of climate change, changes in precipitation will be the hardest to predict. However, studies conducted by the California Natural Resources Agency suggest that there will be more dry days and years in the future with occasional downpours. [7] More specifically, they estimate that the southern and inland regions of the state that are already dry to become more arid over time while the northern part of the state that currently receives a majority of the state's rainfall will continue to get wetter with the onset of climate change. In addition, the increase in atmospheric temperatures will also lessen the amount of precipitation that falls as snow.[5] A 2017 UCLA study found that "anthropogenic warming reduced average snowpack levels by 25%, with mid-to-low elevations experiencing reductions between 26-43%."[11] The implication of this precipitation pattern change is that immediate runoff will increase making the winter months a lot wetter, and that there will be a longer, warmer dry season in the spring and summer months. By the end of the century, the California Department of Water Resources predicts that the Sierra Nevada snowpack, the state's primary freshwater source[12], will decrease by 48-65% from its April 1 average.[6]

Socio-Economic & Political Implications[edit]

Climate change impacts related to water, including sea level rise, more extreme weather conditions, and changes in precipitation, will have various effects in California. The state's water infrastructure, including dams, levees, and canals, are out of date, and they are particularly ill-suited in light of climate change.[5] For instance, decreased snowpack and increased immediate rain runoff will increase the risk of infrastructure failure and flooding in the state. In fact, the state's water management systems are already failing as a result of changing precipitation as was the case in the 2017 Oroville Dam crisis[6]. At the same time that climate change will increase flooding, it will also cause more frequent and extreme droughts as the state's climate continues to become drier over time. By utilizing the Palmer Drought Severity Index, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found that droughts in the state will become more severe in the next 40 years with the onset of climate change.[13] This means that there will be less water for the state to distribute. California's Fourth Climate Change Assessment found that water storage in the state's two largest reservoirs, Shasta and Oroville, will decrease by one third under current management systems.[5] This decreased water storage combined with less spring and summer runoff conflicts with the state's water demand. To date, most of California's precipitation falls as snow in the winter months, and it flows into rivers and streams in the spring and summer months as the snow melts. This is an important aspect of California's water management systems because most of the state's water demand occurs in the late summer months during the agricultural growing season. As temperatures continue to increase this effect will diminish, and the state will have to find a way to store water from the winter months to the summer months when it is most needed.

- ^ Friedlingstein, Pierre; Jones, Matthew; O'Sullivan, Michael; Andrew, Robbie (October 28, 2019). "Global Carbon Budget 2019". Earth Systems Science Data. 11: 1783–1838 – via ESSD.

- ^ Summary for Policy Makers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above preindustrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emissions pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. IPCC. 2018. pp. 1–24.

- ^ "What Climate Change Means for California" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. August 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "Floods in California". Public Policy Institute of California. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d California's Fourth Climate Change Assessment: California's Changing Climate 2018 (PDF). State of California, California Energy Commission, California Natural Resources Agency. 2018. pp. 1–19.

- ^ a b c "Climate Change and Water". California Department of Water Resources. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Climate Change- The Challenge (PDF). California Natural Resources Agency. 2017. pp. 12–24.

- ^ "Climate and Land Use Changes". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Garfin, Gregg (2013). Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States. Island Press. pp. 1–462. ISBN 9781610914468.

- ^ a b State of California Hazard Mitigation Plan (PDF). California Governor's Office of Emergency Services. 2018. pp. 1–1088.

- ^ Berg, Neil (2017). Anthropogenic Warming Impacts on California Snowpack During Drought (PDF). University of California, Los Angeles. pp. 1–23.

- ^ Indicators of Climate Change in California: Report Summary (PDF). Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. 2018. pp. 1–15.

- ^ "Climate at a Glance: Statewide Time Series". NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. April 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)