User:Marek69/Pope John Paul II

Marek69/Pope John Paul II | |

|---|---|

John Paul II in 1993 | |

| Papacy began | 16 October 1978 |

| Papacy ended | 2 April 2005 (26 years, 168 days) |

| Predecessor | John Paul I |

| Successor | Benedict XVI |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1 November 1946 |

| Consecration | 28 September 1958 by Eugeniusz Baziak |

| Created cardinal | 26 June 1967 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Karol Józef Wojtyła 18 May 1920 |

| Died | 2 April 2005 (aged 84) Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Motto | [Totus tuus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 22 October |

| Venerated in | 19 December 2009 |

| Beatified | 1 May 2011 Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City by Pope Benedict XVI |

| Patronage | World Youth Day (Co- Patron) |

| Other popes named John Paul | |

Blessed Pope John Paul II (Latin: Ioannes Paulus PP. II, Italian: Giovanni Paolo II, Polish: Jan Paweł II), born Karol Józef Wojtyła (Polish: [ˈkarɔl ˈjuzɛf vɔjˈtɨwa]; 18 May 1920 – 2 April 2005), served as Pope of theCatholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at 84 years and 319 days of age. At 26 years and 168 days, his was thesecond-longest documented pontificate; only Pope Pius IX (1846–1878) who served 31 years, reigned longer. Pope John Paul II is the only Polish or indeed Slavic Pope to date and was the first non-Italian Pope since Dutch Pope Adrian VI (1522–1523).

John Paul II was acclaimed as one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century. He was instrumental in ending communism in his native Poland and eventually all of Europe. Conversely, he denounced the excesses of capitalism. John Paul II significantly improved the Catholic Church's relations with Judaism, Islam, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Anglican Communion. Though criticised by progressives for upholding the Church's teachings against artificial contraception and the ordination of women and by traditionalists for his support of the Church's Second Vatican Council and its reform, he was also widely praised[1] for his firm, orthodox Catholic stances.

He was one of the most-travelled world leaders in history, visiting 129 countries during his pontificate. He spoke Italian, French, German, English, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Croatian, and Latin as well as his nativePolish. As part of his special emphasis on the universal call to holiness, he beatified 1,340 people and canonised 483 saints, more than the combined tally of his predecessors during the preceding five centuries. On 19 December 2009, John Paul II was proclaimed venerable by his successor Pope Benedict XVI and was beatified on 1 May 2011.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Karol Józef Wojtyła (Anglicised: Charles Joseph Wojtyla) was born in the Polish town of Wadowice[1][2][3] and was the youngest of three children of Karol Wojtyła, an ethnic Pole,[4] and Emilia Kaczorowska, who is described as being of Lithuanian [4] and possibly Ukrainianancestry.[5][6] Emilia died on 13 April 1929,[7] when Wojtyła was eight years old.[8] His elder sister, Olga, had died before his birth, but he was close to his brother Edmund, nicknamed Mundek who was 14 years his senior. Edmund's work as a physician eventually led to his death from scarlet fever.

As a boy, Wojtyła was athletic, often playing football in goal.[9][10] During his childhood Wojtyła had contact with Wadowice's large Jewish community. School football games were often organised between teams of Jews and Catholics, and Wojtyła often played on the Jewish side.[4][9]

In mid-1938, Wojtyła and his father left Wadowice and moved to Kraków, where he enrolled at Jagiellonian University. While studying such topics as philology and various languages, he worked as a volunteer librarian and was required to participate incompulsory military training in the Academic Legion, but he refused to fire a weapon. He performed with various theatrical groups and worked as a playwright.[11] During this time, his talent for language blossomed and he learned as many as 12 foreign languages, nine of which he used extensively as Pope.[2]

In 1939, Nazi German occupation forces closed the university after invading Poland.[2] Able-bodied males were required to work, so from 1940 to 1944 Wojtyła variously worked as a messenger for a restaurant, a manual labourer in a limestone quarry and for the Solvay chemical factory, to avoid deportation to Germany.[3][11] His father, a non-commissioned officer in the Polish Army, died of a heart attack in 1941, leaving Wojtyła as the immediate family's only surviving member.[4][7][12] "I was not at my mother's death, I was not at my brother's death, I was not at my father's death," he said, reflecting on these times of his life, nearly forty years later, "At twenty, I had already lost all the people I loved."[12]

After his father's death, he started thinking seriously about the priesthood.[13] In October 1942, while the war continued, he knocked on the door of the Archbishop's Palace in Kraków, and asked to study for the priesthood.[13] Soon after, he began courses in the clandestine underground seminary run by the Archbishop of Kraków, Adam Stefan Cardinal Sapieha.

On 29 February 1944, Wojtyła was knocked down by a German truck. German Wehrmacht officerstended to him and sent him to a hospital. He spent two weeks there recovering from a severe concussion and a shoulder injury. It seemed to him that this accident and his survival was confirmation of his vocation. On 6 August 1944, ‘Black Sunday’,[14] the Gestapo rounded up young men in Kraków to avoid an uprising similar[14] to the recent uprising in Warsaw.[15][16] Wojtyła escaped by hiding in the basement of his uncle's house at 10 Tyniecka Street, while the German troops searched above.[13][15][16] More than eight thousand men and boys were taken that day, while Wojtyła escaped to the Archbishop's Palace,[13][14][15] where he remained until after the Germans had left.[4][13][17]

On the night of 17 January 1945, the Germans fled the city, and the students reclaimed the ruinedseminary. Wojtyła and another seminarian volunteered for the task of clearing away piles of frozen excrement from the toilets.[18] Wojtyła also helped a 14-year-old Jewish refugee girl named Edith Zierer[19] who had run away from a Nazilabour camp in Częstochowa.[19] Edith had collapsed on a railway platform, so Wojtyła carried her to a train and stayed with her throughout the journey to Kraków.[20] Edith credits Wojtyła with saving her life that day.[21][22][23] B'nai B'rith and other authorities have said that Wojtyła helped protect many other Polish Jews from the Nazis. After the war, while living in Krakow, Wojtyła was involved in a high speed motorbike chase, narrowly escaping from the Polish police.[24]

Priesthood[edit]

On finishing his studies at the seminary in Kraków, Wojtyła was ordained as a priest on All Saints' Day, 1 November 1946,[7] by the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Sapieha.[3][25][26] He then studied theology in Rome, at the Pontifical International Athenaeum Angelicum,[25][26] where he earned alicentiate and later a doctorate in sacred theology.[2] This doctorate, the first of two, was based on the Latin dissertation The Doctrine of Faith According to Saint John of the Cross.

He returned to Poland in the summer of 1948 with his first pastoral assignment in the village of Niegowić, fifteen miles from Kraków. He arrived at Niegowić at harvest time, where his first action was to kneel and kiss the ground.[27] This gesture, which he adapted from French saint Jean Marie Baptiste Vianney,[27] would become a ‘trademark’ action during his Papacy.

In March 1949, Wojtyła was transferred to the parish of Saint Florian in Kraków. He taught ethics at Jagiellonian University and subsequently at the Catholic University of Lublin. While teaching, he gathered a group of about 20 young people, who began to call themselves Rodzinka, the "little family". They met for prayer, philosophical discussion, and to help the blind and sick. The group eventually grew to approximately 200 participants, and their activities expanded to include annualskiing and kayaking trips.[28]

In 1954, he earned a second doctorate, in philosophy,[29] evaluating the feasibility of a Catholic ethic based on the ethical system of phenomenologist Max Scheler. However, the Communist authorities' intervened to prevent him from receiving the degree until 1957.[26]

During this period, Wojtyła wrote a series of articles in Kraków's Catholic newspaper Tygodnik Powszechny ("Universal Weekly") dealing with contemporary church issues.[30] He focused on creating original literary work during his first dozen years as a priest. War, life under Communism, and his pastoral responsibilities all fed his poetry and plays. Wojtyła published his work under two pseudonyms – Andrzej Jawień and Stanisław Andrzej Gruda[11][30][31] – to distinguish his literary from his religious writings (under his own name) and also so that his literary works would be considered on their merits.[11][30][31] In 1960, Wojtyła published the influential theological book Love and Responsibility, a defence of traditional Church teachings on marriage from a new philosophical standpoint.[11][32]

Bishop and cardinal[edit]

On 4 July 1958,[26] while Wojtyła was on a kayaking holiday in the lakes region of northern Poland, Pope Pius XIIappointed him as the auxiliary bishop of Kraków. He was then summoned to Warsaw to meet the Primate of Poland,Stefan Cardinal Wyszyński, who informed him of his appointment.[33][34] He agreed to serve as Auxiliary Bishop to Krakow's Archbishop Eugeniusz Baziak, and he was ordained to the Episcopate (as Titular Bishop ofOmbi) on 28 September 1958. Baziak was the principal consecrator. Then-Auxiliary Bishop Boleslaw Kominek (Titular Bishop ofSophene and Vaga; of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Wroclaw and future Cardinal Archbishop of Wroclaw) and then-Auxiliary Bishop Franciszek Jop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sandomierz (Titular Bishop of Daulia; later Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Wroclaw and then Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Opole) were the principal co-consecrators.[26]At the age of 38, Wojtyła became the youngest bishop in Poland. Baziak died in June 1962 and on 16 July Wojtyła was selected as Vicar Capitular (temporary administrator) of the Archdiocese until an Archbishop could be appointed.[2][3]

In October 1962, Wojtyła took part in the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965),[2][26] where he made contributions to two of its most historic and influential products, the Decree on Religious Freedom (in Latin, Dignitatis Humanae) and the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes).[26]

He also participated in the assemblies of the Synod of Bishops.[2][3] On 13 January 1964, Pope Paul VI appointed him Archbishop of Kraków.[35] On 26 June 1967, Paul VI announced Archbishop Karol Wojtyła's promotion to the Sacred College of Cardinals.[1][26][35] Wojtyła was named Cardinal-Priest of the titulus of San Cesareo in Palatio.[36]

In 1967, he was instrumental in formulating the encyclical Humanae Vitae, which dealt with the same issues that forbidabortion and artificial birth control.[1][26][37][38]

Election to the Papacy[edit]

| Papal styles of Marek69/Pope John Paul II | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Blessed |

In August 1978, following the death of Pope Paul VI, Cardinal Wojtyła voted in the Papal conclave which elected Pope John Paul I, who at 65 was considered young by papal standards. John Paul I died after only 33 days as Pope, triggering another conclave.[3][26][39]

The second conclave of 1978 started on 14 October, ten days after the funeral. It was split between two strong candidates for the papacy: Giuseppe Cardinal Siri, the conservative Archbishop of Genoa, and theliberal Archbishop of Florence, Giovanni Cardinal Benelli, a close friend of John Paul I.[40]

Supporters of Benelli were confident that he would be elected, and in early ballots, Benelli came within nine votes of success.[40] However, both men faced sufficient opposition that neither was likely to prevail. Franz Cardinal König,Archbishop of Vienna suggested to his fellow electors a compromise candidate: the Polish Cardinal, Karol Józef Wojtyła.[40] Wojtyła won on the eighth ballot on the second day with, according to the Italian press, 99 votes from the 111 participating electors. He subsequently chose the name John Paul II[26][40] in honour of his immediate predecessor, and the traditional white smoke informed the crowd gathered in St. Peter's Square that a pope had been chosen.[39] He accepted his election with these words: ‘With obedience in faith to Christ, my Lord, and with trust in the Mother of Christ and the Church, in spite of great difficulties, I accept.’[41][42] When the new pontiff appeared on the balcony, he broke tradition by addressing the gathered crowd:[41]

| “ | Dear brothers and sisters, we are saddened at the death of our beloved Pope John Paul I, and so the cardinals have called for a new bishop of Rome. They called him from a faraway land – far and yet always close because of our communion in faith and Christian traditions. I was afraid to accept that responsibility, yet I do so in a spirit of obedience to the Lord and total faithfulness to Mary, our most Holy Mother. I am speaking to you in your – no, our Italian language. If I make a mistake, please ‘kirrect’ [sic] me...[41][43] | ” |

| — John Paul II | ||

Wojtyła became the 264th Pope according to the chronological list of popes, the first non-Italian in 455 years.[44] At only 58 years of age, he was the youngest pope since Pope Pius IX in 1846, who was 54.[26] Like his predecessor, Pope John Paul II dispensed with the traditional Papal coronation and instead received ecclesiastical investiture with the simplified Papal inauguration on 22 October 1978. During his inauguration, when the cardinals were to kneel before him to take their vows and kiss his ring, he stood up as the Polish prelate Stefan Cardinal Wyszyński knelt down, stopped him from kissing the ring, and simply hugged him.[45]

Life's work[edit]

Pastoral trips[edit]

During his pontificate, Pope John Paul II made trips to 129 countries,[46] travelling more than 1,100,000 kilometres (680,000 mi)whilst doing so. He consistently attracted large crowds, some amongst the largest ever assembled in human historysuch as the Manila World Youth Day, which gathered around 5 million people.[47] Some have suggested that it may have been the largest Christian gathering ever.[48]

John Paul II's earliest official visits were to the Dominican Republic and Mexico in January 1979 and to Poland in June 1979,[49] where ecstatic crowds constantly surrounded him.[50] This first trip to Poland uplifted the nation's spirit and sparked the formation of the Solidarity movement in 1980, which later brought freedom and human rights to his troubled homeland.[37] On later trips to Poland, he gave tacit support to the organization.[37] Successive Polish trips reinforced this message and contributed to the collapse of East European Communism that took place between 1989/1990 with the reintroduction of democracy in Poland, and which then spread through Eastern Europe (1990–1991) and South-Eastern Europe (1990–1992).[43][46][50][51][52][53]

While some of his trips (such as to the United States and the Holy Land) were to places previously visited by Pope Paul VI, John Paul II became the first pope to visit the White House in October 1979, where he was greeted warmly by then-President Jimmy Carter. He was the first Pope ever to visit several countries, starting in 1979 with Mexico,[54] and Ireland.[55][56] He was the first reigning pope to travel to the United Kingdom, in 1982,[57] where he met Queen Elizabeth II, the Supreme Governor of the Church of England.[57] He travelled to Haiti in 1983, where he spoke in Creole to thousands of impoverished Catholics gathered to greet him at the airport. His message, "things must change in Haiti", referring to the disparity between the wealthy and the poor, was met with thunderous applause.[58] In 2000, he was the first modern pope to visit Egypt,[59]where he met with the Coptic pope, Pope Shenouda III[59] and the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria.[59][60] He was the first Catholic pope to visit and pray in an Islamic mosque, in Damascus, Syria, in 2001. He visited the Umayyad Mosque, a former Christian church where John the Baptist is believed to be interred,[61] where he made a speech calling for Muslims, Christians and Jews to live together.[61][62]

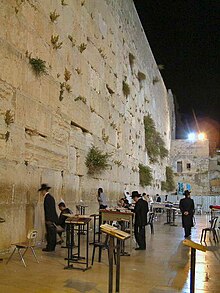

On 15 January 1995, during the X World Youth Day, he offered Mass to an estimated crowd of between five and seven million in Luneta Park,[47] Manila, Philippines, which was considered to be the largest single gathering in Christian history.[47] In March 2000, while visiting Jerusalem, John Paul became the first pope in history to visit and pray at the Western Wall.[63][64] In September 2001, amid post-11 September concerns, he travelled to Kazakhstan, with an audience largely consisting of Muslims, and to Armenia, to participate in the celebration of 1,700 years of Armenian Christianity.[65]

| “ | Today, for the first time in history, a Bishop of Rome sets foot on English soil. This fair land, once a distant outpost of thepagan world, has become, through the preaching of the Gospel, a beloved and gifted portion of Christ's vineyard.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II (1982) | ||

|

Pope John Paul II’s World Travels:[49][67]

|

|

Relationship with young people[edit]

John Paul II had a special relationship with Catholic youth and is known by some as The Pope for Youth.[68][69] Before he was pontiff, he used to camp and mountain hike with groups of young people. He countinued mountain hiking as pope.[68] He was concerned with priestly education and made many early visits to Roman seminaries, including to the Venerable English College in 1979.[3] He established World Youth Day in 1984 with the intention of bringing young Catholics from all parts of the world together to celebrate the faith.[3][68][69] These weeklong meetings occur every two or three years, attracting hundreds of thousands of young people, who go there to sing, have a good time and deepen their faith.[3][69] The 19 World Youth Days celebrated during his pontificate brought together millions of young people from all over the world. During this time, his care for the family was expressed in the World Meetings of Families, which he initiated in 1994.[3]

| “ | Young people are threatened... by the evil use of advertising techniques that stimulate the natural inclination to avoid hard work by promising the immediate satisfaction of every desire.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

| “ | Young people of the world, hear His voice! Hear His voice and follow Him![70] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

Relations with other faiths[edit]

Pope John Paul II travelled extensively and met with believers from many divergent faiths. He constantly attempted to find common ground, both doctrinal and dogmatic. At the World Day of Prayer for Peace, held inAssisi on 27 October 1986, more than 120 representatives of different religions and Christian denominations spent a day together with fasting and praying.[71]

Anglicanism[edit]

Pope John Paul II had good relations with the Church of England, referred to by his predecessor Pope Paul VI, as "our beloved Sister Church".[72] He preached in Canterbury Cathedral during his visit to London,[57] and received the Archbishop of Canterbury with friendship and courtesy.[57] However, John Paul II was disappointed by the Church of England's decision to offer the Sacrament of Holy Orders to women and saw it as a step in the opposite direction from unity between theAnglican Communion and the Catholic Church.[72]

In 1980 John Paul II issued a Pastoral Provision allowing married former Episcopal priests to become Catholic priests, and for the acceptance of former Episcopal Church parishes into the Catholic Church. He allowed the creation of theAnglican Use form of the Latin Rite, which incorporates the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. John Paul II's historic ecumenical effort with the Anglican Communion was realised with the establishment of Our Lady of the Atonement Catholic Church (Anglican Use), in cooperation with Archbishop Patrick Flores of San Antonio, TX, in the United States.[73]

Buddhism[edit]

Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama visited Pope John Paul II eight times, more than any other single dignitary. The Pope and the Dalai Lama held many similar views and understood similar plights, both coming from people damaged by communism and both serving as heads of major religious bodies.[74][75]

Eastern Orthodox Church[edit]

In May 1999, John Paul II visited Romania on the invitation from Patriarch Teoctist Arăpaşu of the Romanian Orthodox Church. This was the first time a Pope had visited a predominantly Eastern Orthodox country since the Great Schism in 1054.[76] On his arrival, the Patriarch and the President of Romania, Emil Constantinescu, greeted the Pope.[76] The Patriarch stated, "The second millennium of Christian history began with a painful wounding of the unity of the Church; the end of this millennium has seen a real commitment to restoring Christian unity."[76]

On 23–27 June 2001 John Paul II visited Ukraine, another heavily Orthodox nation, at the invitation of the President of Ukraine and bishops of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[77] The Pope spoke to leaders of the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organisations, pleading for "open, tolerant and honest dialogue".[77] About 200 thousand people attended the liturgies celebrated by the Pope in Kiev, and the liturgy in Lviv gathered nearly one and a half million faithful.[77] John Paul II stated that an end to the Great Schism was one of his fondest wishes.[77] Healing divisions between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches regarding Latin and Byzantinetraditions was clearly of great personal interest. For many years, John Paul II sought to facilitate dialogue and unity stating as early as 1988 in Euntes in mundum that "Europe has two lungs, it will never breathe easily until it uses both of them".

During his 2001 travels, John Paul II became the first Pope to visit Greece in 1291 years.[78][79] In Athens, the Pope met with Archbishop Christodoulos, the head of the Greek Orthodox Church.[78] After a private 30 minute meeting, the two spoke publicly. Christodoulos read a list of "13 offences" of the Roman Catholic Church against the Eastern Orthodox Church since the Great Schism,[78] including the pillaging of Constantinople by crusaders in 1204, and bemoaned the lack of apology from the Roman Catholic Church, saying "Until now, there has not been heard a single request for pardon" for the "maniacal crusaders of the 13th century."[78]

The Pope responded by saying "For the occasions past and present, when sons and daughters of the Catholic Church have sinned by action or omission against their Orthodox brothers and sisters, may the Lord grant us forgiveness," to which Christodoulos immediately applauded. John Paul II said that the sacking of Constantinople was a source of "profound regret" for Catholics.[78] Later John Paul and Christodoulos met on a spot where Saint Paul had once preached to Athenian Christians. They issued a ‘common declaration’, saying "We shall do everything in our power, so that the Christian roots of Europe and its Christian soul may be preserved. … We condemn all recourse to violence, proselytism and fanaticism, in the name of religion".[78] The two leaders then said the Lord's Prayer together, breaking an Orthodox taboo against praying with Catholics.[78]

The Pope had said throughout his pontificate that one of his greatest dreams was to visit Russia, but this never occurred. He attempted to solve the problems that had arisen over centuries between the Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches, and in 2004 gave them a 1730 copy of the lost icon of Our Lady of Kazan.

Islam[edit]

Pope John Paul II made considerable efforts to improve relations between Catholicism and Islam.[80]

On 6 May 2001, Pope John Paul II became the first Catholic pope to enter and pray in a mosque. Respectfully removing his shoes, he entered the Umayyad Mosque, a former Byzantine era Christian church dedicated to John the Baptist (who was believed to be interred there) in Damascus, Syria, and gave a speech including the statement: "For all the times that Muslims and Christians have offended one another, we need to seek forgiveness from the Almighty and to offer each other forgiveness."[61][62] He kissed the Qur’an in Syria,[81][82][83] an act which made him popular amongst Muslims but which disturbed many Catholics.[82]

In 2004, Pope John Paul II hosted the "Papal Concert of Reconciliation", which brought together leaders of Islam with leaders of the Jewish community and of the Catholic Church at the Vatican for a concert by the Kraków Philharmonic Choir from Poland, the London Philharmonic Choir from the United Kingdom, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from the United States, and the AnkaraState Polyphonic Choir of Turkey.[84][85][86][87] The event was conceived and conducted by Sir Gilbert Levine, KCSG and was broadcast throughout the world.[84][85][86][87]

John Paul II oversaw the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church which makes a special provision[clarification needed] for Muslims; therein, it is written, "The plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator, in the first place amongst whom are the Muslims; these profess to hold the faith of Abraham, and together with us they adore the one, merciful God, mankind's judge on the last day."[88]

Judaism[edit]

Relations between Catholicism and Judaism improved during the pontificate of John Paul II.[37][64] He spoke frequently about the Church's relationship with the Jewish faith.[37]

In 1979, John Paul II became the first pope to visit the German Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, where many of his compatriots (mostly Polish Jews) had perished during the Nazi occupation in World War II. In 1998 he issued "We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah" which outlined his thinking on the Holocaust.[89] He became the first pope known to have made an official papal visit to a synagogue,[90] when he visited the Great Synagogue of Romeon 13 April 1986.[91][92][93]

In 1994, John Paul II established formal diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the State of Israel, acknowledging its centrality in Jewish life and faith.[91][94] In honour of this event, Pope John Paul II hosted ‘The Papal Concert to Commemorate the Holocaust’. This concert, which was conceived and conducted by American Maestro Gilbert Levine, was attended by the Chief Rabbi of Rome, the President of Italy, and survivors of the Holocaust from around the world.[95][96]

In March 2000, John Paul II visited Yad Vashem, the national Holocaust memorial in Israel, and later made history by touching one of the holiest sites in Judaism, the Western Wall in Jerusalem,[64] placing a letter inside it (in which he prayed for forgiveness for the actions against Jews).[63][64][91][97] In part of his address he said: "I assure the Jewish people the Catholic Church ... is deeply saddened by the hatred, acts of persecution and displays of anti-Semitism directed against the Jews by Christians at any time and in any place", he added that there were "no words strong enough to deplore the terrible tragedy of the Holocaust".[63][64] Israeli cabinet minister Rabbi Michael Melchior, who hosted the Pope's visit, said he was "very moved" by the Pope's gesture.[63][64]

| “ | It was beyond history, beyond memory.[63] | ” |

| — Rabbi Michael Melchior (26 March 2000) | ||

| “ | We are deeply saddened by the behaviour of those who in the course of history have caused these children of yours to suffer, and asking your forgiveness we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant.[97][98] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II (12 March 2000) from a note left by the Pope at the Western Wall in Jerusalem | ||

In October 2003, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) issued a statement congratulating John Paul II on entering the 25th year of his papacy.[94] In January 2005, John Paul II became the first Pope in history known to receive a priestly blessing from a rabbi, when Rabbis Benjamin Blech, Barry Dov Schwartz, and Jack Bemporad visited the Pontiff at Clementine Hallin the Apostolic Palace.[99]

Immediately after John Paul II's death, the ADL issued a statement that Pope John Paul II had revolutionised Catholic-Jewish relations, saying that "more change for the better took place in his 27 year Papacy than in the nearly 2,000 years before."[100] In another statement issued by the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council, Director Dr Colin Rubenstein said, "The Pope will be remembered for his inspiring spiritual leadership in the cause of freedom and humanity. He achieved far more in terms of transforming relations with both the Jewish people and the State of Israel than any other figure in the history of the Catholic Church".[91]

| “ | With Judaism, therefore, we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers, and in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II (13 April 1986) | ||

Lutheranism[edit]

On 15–19 November 1980 John Paul II visited the Federal Republic of Germany[101] on his first trip to a country with a large Lutheran population. In Mainz he met with leaders of the Lutheran and other Protestant Churches, and with representatives of other Christian denominations.

11 December 1983 John Paul II participated in an ecumenical service in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Rome,[102] the first papal visit ever to a Lutheran church. The visit took place 550 years after the birth of Martin Luther, the German Augustinian monk who initiated the Lutheran reformation.

In his apostolic pilgrimage to Norway, Iceland, Finland, Denmark and Sweden of June 1989,[103] John Paul II became the first pope to visit countries with Lutheran majorities. In addition to celebrating Mass with Catholic believers, he participated in ecumenical services at places that had been Catholic shrines before the 16th century Lutheran reformation: Nidaros Cathedral in Norway; near St. Olav's Church at Thingvellir in Iceland; Turku Cathedral in Finland; Roskilde Cathedral in Denmark; and Uppsala Cathedral in Sweden.

On 31 October 1999 (the 482nd anniversary of Reformation Day, Martin Luther's posting of the 95 Theses), representatives of the Vatican and the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) signed a Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, as a gesture of unity. The signing was a fruit of a theological dialogue that had been going on between the LWF and the Vatican since 1965.[104]

Role in the fall of Communism[edit]

John Paul II has been credited with being instrumental in bringing down communism in Central and Eastern Europe,[37][43][46][51][52][53][105] by being the spiritual inspiration behind its downfall, and a catalyst for "a peaceful revolution" in Poland. Lech Wałęsa, the founder of‘Solidarity’, credited John Paul II with giving Poles the courage to demand change.[37] According to Wałęsa, "Before his pontificate, the world was divided into blocs. Nobody knew how to get rid of communism. InWarsaw, in 1979, he simply said: 'Do not be afraid', and later prayed: 'Let your Spirit descend and change the image of the land... this land'."[105][106]

President Ronald Reagan's correspondence with the pope reveals "a continuous scurrying to shore up Vatican support for U.S. policies. Perhaps most surprisingly, the papers show that, as late as 1984, the pope did not believe the Communist Polish government could be changed."[107]

In December 1989, John Paul II met with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at the Vatican and each expressed his respect and admiration for the other. Gorbachev once said ‘The collapse of the Iron Curtain would have been impossible without John Paul II’.[43][51] On John Paul's passing, Mikhail Gorbachev said: "Pope John Paul II's devotion to his followers is a remarkable example to all of us."[53][105][108]

In February 2004, Pope John Paul II was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize honouring his life's work in opposing Communist oppression and helping to reshape the world.[109]

President George W. Bush presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian honour, to Pope John Paul II during a ceremony at the Vatican 4 June 2004. The president read the citation that accompanied the medal, which recognised "this son of Poland" whose "principled stand for peace and freedom has inspired millions and helped to topple communism and tyranny." After receiving the award, John Paul II said, "May the desire for freedom, peace, a more humane world symbolised by this medal inspire men and women of goodwill in every time and place."[110]

| “ | Warsaw, Moscow, Budapest, Berlin, Prague, Sofia and Bucharest have become stages in a long pilgrimage toward liberty. It is admirable that in these events, entire peoples spoke out – women, young people, men, overcoming fears, their irrepressible thirst for liberty speeded up developments, made walls tumble down and opened gates. [52] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II (1989) | ||

Assassination attempts[edit]

As he entered St. Peter's Square to address an audience on May 13, 1981,[111] John Paul II was shot and critically wounded by Mehmet Ali Ağca,[2][46][112] an expert Turkish gunman who was a member of the militant fascist group Grey Wolves.[113] The assassin used a Browning 9 mm semi-automatic pistol,[114] shooting him in the abdomen and perforating his colon and small intestine multiple times.[43] John Paul II was rushed into the Vatican complex and then to the Gemelli Hospital. En route to the hospital, he lost consciousness. Even though the bullets missed his mesenteric artery and abdominal aorta, he lost nearly three-quarters of his blood. He underwent five hours of surgery to treat his wounds.[115] Surgeons performed a colostomy, temporarily rerouting the upper part of the large intestine to let the damaged lower part heal.[115] When he briefly gained consciousness before being operated on, he instructed the doctors not to remove his Brown Scapular during the operation.[116][117] The pope stated that Our Lady of Fátima helped keep him alive throughout his ordeal.[46][112][118]

| “ | Could I forget that the event [Ali Ağca's assassination attempt] in St. Peter’s Square took place on the day and at the hour when the first appearance of the Mother of Christ to the poor little peasants has been remembered for over sixty years at Fátima, Portugal? For in everything that happened to me on that very day, I felt that extraordinary motherly protection and care, which turned out to be stronger than the deadly bullet.[119] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

Ağca was caught and restrained by a nun and other bystanders until police arrived. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Two days after Christmas in 1983, John Paul II visited Ağca in prison. John Paul II and Ağca spoke privately for about twenty minutes.[46][112] John Paul II said, "What we talked about will have to remain a secret between him and me. I spoke to him as a brother whom I have pardoned and who has my complete trust.″

On 2 March 2006 the Italian parliament's Mitrokhin Commission, set up by Silvio Berlusconi and headed by Forza Italia senatorPaolo Guzzanti, concluded that the Soviet Union was behind the attempt on John Paul II's life,[113][120] in retaliation for the pope's support of Solidarity, the Catholic, pro-democratic Polish workers' movement, a theory which had already been supported by Michael Ledeen and the United States Central Intelligence Agency at the time.[113][120] The Italian report stated that Communist Bulgarian security departments were utilised to prevent the Soviet Union's role from being uncovered.[120] The report stated thatSoviet military intelligence (Glavnoje Razvedyvatel'noje Upravlenije), not the KGB, were responsible.[120] Russian Foreign Intelligence Service spokesman Boris Labusov called the accusation‘absurd’.[120] The Pope declared during a May 2002 visit to Bulgaria that the country's Soviet bloc-era leadership had nothing to do with the assassination attempt.[113][120] However, his secretary, Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, alleged in his book A Life with Karol, that the pope was convinced privately that the former Soviet Union was behind the attack.[121] It was later discovered that many of John Paul II's aides had foreign government attachments;[122][123] Bulgaria and Russia disputed the Italian commission's conclusions, pointing out that the Pope had publicly denied the Bulgarian connection.[120][124] A second assassination attempt took place on 12 May 1982, just a day before the anniversary of the first attempt on his life, in Fátima, Portugal when a man tried to stab John Paul II with a bayonet.[125][126][127] He was stopped by security guards, although Stanisław Cardinal Dziwisz later claimed that John Paul II had been injured during the attempt but managed to hide a non-life threatening wound.[125][126][127] The assailant, a traditionalist Spanish priest named Juan María Fernández y Krohn,[125] was ordained as a priest by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre of the Society of Saint Pius X and was opposed to the changes caused by theSecond Vatican Council, claiming that the pope was an agent of Communist Moscow and of the Marxist Eastern Bloc.[128] Fernández y Krohn subsequently left the priesthood and served three years of a six-year sentence.[126][127][128] The ex-priest was treated for mental illness and then expelled from Portugal to become a solicitor in Belgium.[128]

Pope John Paul II was also a target of the Al-Qaeda-funded Operation Bojinka during a visit to the Philippines in 1995. The first plan was to kill him in the Philippines during World Youth Day 1995 celebrations. On 15 January 1995, a suicide bomber was planning to dress as a priest, while John Paul II passed in his motorcade on his way to the San Carlos Seminary in Makati City. The would-be-assassin intended to get close and detonate the bomb. The assassination was intended to divert attention from the next phase of the operation. However, a chemical fire inadvertently started by the cell alerted police to their whereabouts, and all were arrested a week before the Pope's visit, confessing to the plot.[129]

Social and political stances[edit]

John Paul II was considered a conservative on doctrine and issues relating to sexual reproduction, and the ordination of women.[130]

While the Pope was visiting the United States of America he said, "All human life, from the moments of conception and through all subsequent stages, is sacred."[131]

A series of 129 lectures given by John Paul during his Wednesday audiences in Rome between September 1979 and November 1984 were later compiled and published as a single work entitled ‘Theology of the Body’, an extended meditation on human sexuality. He extended it to condemnation of abortion, euthanasia and virtually all capital punishment,[132] calling them all a part of the "culture of death" that is pervasive in the modern world. He campaigned for world debt forgiveness andsocial justice.[37][130]

Liberation theology[edit]

In 1984 and 1986, through Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), then-leader of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, John Paul II officially condemned aspects of Liberation theology, which had many followers in South America. Visiting Europe, Óscar Romero unsuccessfully attempted to obtain a Vatican condemnation of El Salvador's regime, for violations of human rights and its support of death squads. In his travel to Managua, Nicaragua in 1983, John Paul II harshly condemned what he dubbed the "popular Church"[133] (i.e. "ecclesial base communities" supported by the CELAM), and the Nicaraguan clergy's tendencies to support the leftist Sandinistas, reminding the clergy of their duties of obedience to the Holy See.[133] During that visit Ernesto Cardenal, a priest and minister in the Sandinista government, knelt to kiss his hand. John Paul withdrew it, wagged his finger in Cardenal's face, and told him, "You must straighten out your position with the church."[134]

Jubilee 2000 campaign[edit]

In 2000, he publicly endorsed the Jubilee 2000 campaign on African debt relief fronted by Irish rock stars Bob Geldof andBono, once famously interrupting a U2 recording session by telephoning the studio and asking to speak to Bono.[135]

Iraq war[edit]

In 2003, John Paul II became a prominent critic of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.[37] In his 2003 State of the World address, the Pope declared his opposition to the invasion by stating, "No to war! War is not always inevitable. It is always a defeat for humanity."[136] He sent former Apostolic Pro-Nuncio to the United States Pío Cardinal Laghi to talk with American President George W. Bush to express papal opposition. John Paul II said that it was up to the United Nations to solve the international conflict through diplomacy and that unilateral aggression is a crime against peace and a violation of international law.

| “ | Wars generally do not resolve the problems for which they are fought and therefore... prove ultimately futile.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

Evolution[edit]

- See also: Evolution and the Roman Catholic Church and Scientific theories and the interpretation of Genesis.

On 22 October 1996, in a speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences plenary session at the Vatican, Pope John Paul II said of evolution that "this theory has been progressively accepted by researchers, following a series of discoveries in various fields of knowledge. The convergence, neither sought nor fabricated, of the results of work that was conducted independently is in itself a significant argument in favour of this theory." The Pope qualified this by noting that, "rather than the theory of evolution, we should speak of several theories of evolution." Some of these theories, he noted, have a purely materialistic philosophical underpinning which is not compatible with the Catholic faith: "Consequently, theories of evolution which, in accordance with the philosophies inspiring them, consider the mind as emerging from the forces of living matter, or as a mere epiphenomenon of this matter, are incompatible with the truth about man".[137][138][139][140]

Although generally accepting the theory of evolution, John Paul II made one major exception – the human soul. "If the human body has its origin in living material which pre-exists it, the spiritual soul is immediately created by God".[137][139][140]

Views on sexuality[edit]

While taking a traditional position on sexuality, defending the Church's moral opposition to marriage for same-sex couples, the pope asserted that persons with homosexual inclinations possess the same inherent dignity and rights as everybody else. In his last book, Memory and Identity, he referred to the "pressures" on the European Parliament to permit "homosexual 'marriage'". In the book, as quoted by Reuters, he wrote: "It is legitimate and necessary to ask oneself if this is not perhaps part of a new ideology of evil, perhaps more insidious and hidden, which attempts to pit human rights against the family and against man."[37] A 1997 study determined that 3% of the pope's statements were about the issue of sexual morality.[141]

Health[edit]

When he became pope in 1978, John Paul II was still an avid sportsman. At the time, the 58-year old was extremely healthy and active, jogging in the Vatican gardens, weight training, swimming, and hiking in the mountains. He was fond of football. The media contrasted the new Pope's athleticism and trim figure to the poor health of John Paul I and Paul VI, the portliness of John XXIII and the constant claims of ailments of Pius XII. The only modern pope with a fitness regimen had been Pope Pius XI (1922–1939) who was an avid mountaineer.[142][143] An Irish Independent article in the 1980s labelled John Paul II the keep-fit pope.

However, after over twenty-five years on the papal throne, two assassination attempts (one of which resulted in severe physical injury to the Pope), and a number of cancer scares, John Paul's physical health declined.

Death and funeral[edit]

On 31 March 2005 following a urinary tract infection,[144] Pope John Paul II developed septic shock, a form of infection with a high fever and low blood pressure, but was not hospitalized. Instead, he was monitored by a team of consultants at his private residence. This was taken as an indication that the pope and those close to him believed that he was nearing death; it would have been in accordance with his wishes to die in the Vatican.[145] Later that day, Vatican sources announced that John Paul II had been given the Anointing of the Sick by his friend and secretary Stanisław Dziwisz. During the final days of the Pope's life, the lights were kept burning through the night where he lay in the Papal apartment on the top floor of the Apostolic Palace. Tens of thousands of people assembled and held vigil in St. Peter's Square and the surrounding streets for two days. Upon hearing of this, the dying pope was said to have stated: "I have searched for you, and now you have come to me, and I thank you."[146]

On Saturday 2 April 2005, at about 15:30 CEST, John Paul II spoke his final words, "pozwólcie mi odejść do domu Ojca", ("Let me depart to the house of the Father"), to his aides, and fell into a coma about four hours later.[146][147] The mass of the vigil of the Second Sunday of Easter commemorating thecanonisation of Saint Maria Faustina on 30 April 2000,[148] had just been celebrated at his bedside, presided over by Stanisław Dziwisz and two Polish associates. Present at the bedside was a cardinal fromUkraine who served as a priest with John Paul in Poland, along with Polish nuns of the Congregation of the Sisters Servants of the MostSacred Heart of Jesus, who ran the papal household. He died in his private apartment, at 21:37 CEST[147][149][150] (19:37 UTC) of heart failure from profound hypotension and complete circulatory collapse from septic shock, 46 days short of his 85th birthday. John Paul had no close family by the time he died, and his feelings are reflected in his words, as written in 2000, at the end of his Last Will and Testament:[151]

| “ | As the end of my earthly life approaches, I return with my memory to its beginning, to my parents, my brother and the sister (whom I never knew because she died before my birth), to the Parish of Wadowice where I was baptised, to that city I love, to my peers, friends from elementary school, high school and the university, up to the time of the occupation when I was a worker, then in the Parish in Niegowic, to St Florian's in Kraków, to the pastoral ministry of academics, to the milieu of... to all milieux... to Kraków and to Rome... to the people who were entrusted to me in a special way by the Lord.[151] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

The death of the pontiff set in motion rituals and traditions dating back to medieval times. The Rite of Visitation took place from 4 to 7 April at St. Peter's Basilica. The Testament of Pope John Paul II published on 7 April[152] revealed that the pontiff contemplated being buried in his native Poland but left the final decision to The College of Cardinals, which in passing, preferred burial beneath St. Peter's Basilica, honouring the pontiff's request to be placed "in bare earth". The Mass of Requiem on 8 April was said to have set world records both for attendance and number of heads of state present at a funeral.[153][154][155][156] (See: List of Dignitaries). It was the single largest gathering of heads of state in history, surpassing the funerals of Winston Churchill (1965) and Josip Broz Tito (1980). Four kings, five queens, at least 70 presidents and prime ministers, and more than 14 leaders of other religions attended alongside the faithful.[154] It is likely to have been the largest single pilgrimage of Christianity in history, with numbers estimated in excess of four million mourners gathering in Rome.[153][155][156][157] Between 250,000 and 300,000 watched the event from within the Vatican walls.[156] The Dean of the College of Cardinals, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who would become the next pope, conducted the ceremony. John Paul II was interred in the grottoes under the basilica, the Tomb of the Popes. He was lowered into a tomb created in the same alcove previously occupied by the remains of Pope John XXIII. The alcove had been empty since Pope John's remains had been moved into the main body of the basilica after his beatification.

Posthumous recognition[edit]

Title "the Great"[edit]

Upon the death of John Paul II, a number of clergy at the Vatican and laymen throughout the world[43][153][158] began referring to the late pontiff as "John Paul the Great"—only the fourth pope to be so acclaimed, and the first since the first millennium.[43][158][159][160] Scholars of Canon Law say that there is no official process for declaring a pope "Great"; the title simply establishes itself through popular and continued usage,[153][161][162] as was the case with celebrated secular leaders (for example, Alexander III of Macedon became popularly known as Alexander the Great). The three popes who today commonly are known as "Great" are Leo I, who reigned from 440–461 and persuaded Attila the Hun to withdraw from Rome; Gregory I, 590–604, after whom the Gregorian Chant is named; and Pope Nicholas I, 858–867.[158]

His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, referred to him as "the great Pope John Paul II" in his first address[163] from theloggia of St. Peter's Church, and Angelo Cardinal Sodano referred to Pope John Paul II as "the Great" in his published written homily for the Mass of Repose.[164]

Since giving his homily at the funeral of Pope John Paul, Pope Benedict XVI has continued to refer to John Paul II as "the Great." At the20th World Youth Day in Germany 2005, Pope Benedict XVI, speaking in Polish, John Paul's native language, said, "As the Great Pope John Paul II would say: keep the flame of faith alive in your lives and your people." In May 2006, Pope Benedict XVI visited John Paul's native Poland. During that visit, he repeatedly made references to "the great John Paul" and "my great predecessor".[165]

In addition to the Vatican calling him "the great," numerous newspapers have done so. For example, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera called him "the Greatest" and the South African Catholic newspaper, The Southern Cross, has called him "John Paul II The Great".[166]

Some schools in the United States, such as John Paul the Great Catholic University and John Paul the Great Catholic High School, have recently been named for John Paul II using this title.

Beatification[edit]

Inspired by calls of "Santo Subito!" ("Saint Immediately!") from the crowds gathered during the funeral mass which he performed,[153][167][168][169][170][171] Benedict XVI began the beatification process for his predecessor, bypassing the normal restriction that five years must pass after a person's death before beginning the beatification process.[169][168][172][173] In an audience with Pope Benedict XVI, Camillo Ruini, Vicar General of the Diocese of Rome who was responsible for promoting the cause for canonisation of any person who died within that diocese, cited "exceptional circumstances" which suggested that the waiting period could be waived.[3][153][174][175] This decision was announced on 13 May 2005, the Feast of Our Lady of Fátima and the 24th anniversary of the assassination attempt on John Paul II at St. Peter's Square.[176]

In early 2006, it was reported that the Vatican was investigating a possible miracle associated with John Paul II. Sister Marie Simon-Pierre, a French nun and a member of the Congregation of Little Sisters of Catholic Maternity Wards, confined to her bed byParkinson's Disease,[169][177] was reported to have experienced a "complete and lasting cure after members of her community prayed for the intercession of Pope John Paul II".[153][167][169][178][179][180] As of May 2008[update], Sister Marie-Simon-Pierre, then 46,[167][169] was working again at a maternity hospital run by her order.[173][177][181][182]

"I was sick and now I am cured," she told reporter Gerry Shaw. "I am cured, but it is up to the church to say whether it was a miracle or not."[177][181]

On 28 May 2006, Pope Benedict XVI said Mass before an estimated 900,000 people in John Paul II's native Poland. During his homily, he encouraged prayers for the early canonisation of John Paul II and stated that he hoped canonisation would happen "in the near future."[177][183]

In January 2007, Stanisław Cardinal Dziwisz of Kraków, his former secretary, announced that the interview phase of the beatification process, in Italy and Poland, was nearing completion.[153][177][184] In February 2007, relics of Pope John Paul II—pieces of white papal cassocks he used to wear—were freely distributed with prayer cards for the cause, a typical pious practice after a saintly Catholic's death.[185][186]

On 8 March 2007, the Vicariate of Rome announced that the diocesan phase of John Paul's cause for beatification was at an end. Following a ceremony on 2 April 2007 – the second anniversary of the Pontiff's death – the cause proceeded to the scrutiny of the committee of lay, clerical, and episcopal members of the Vatican's Congregation for the Causes of Saints, to conduct a separate investigation.[168][177][184]

On the fourth anniversary of Pope John Paul's death, 2 April 2009, Cardinal Dziwisz, told reporters of a presumed miracle that had recently occurred at the former pope's tomb in St. Peter's Basilica.[181][187][188][189][190][191][192] A nine year-old Polish boy from Gdańsk, who was suffering from kidney cancer and was completely unable to walk, had been visiting the tomb with his parents. On leaving St. Peter's Basilica, the boy told them, "I want to walk," and began walking normally.[181][187][188][189][190][191][192]

On 16 November 2009, a panel of reviewers at the Congregation for the Causes of Saints voted unanimously that Pope John Paul II had lived a life of virtue.[193][194] On 19 December 2009, Pope Benedict XVI signed the first of two decrees needed for beatification and proclaimed John Paul II "Venerable", asserting that he had lived a heroic, virtuous life.[193][194] The second vote and the second signed decree certify the authenticity of his first miracle (Sister Marie Simon-Pierre). Once the second decree is signed, the positio (the report on the cause, with documentation about his life and writings and with information on the cause) is complete.[194] He can then be beatified.[193][194] Some speculated that he would be beatified sometime during (or soon after) the month of the 32nd anniversary of his 1978 election, in October 2010. As Monsignor Oder noted, this course would have been possible if the second decree were signed in time by Benedict XVI, stating that a posthumous miracle directly attributable to his intercession had occurred, completing the positio.

The Vatican announced on 14 January 2011 that Pope Benedict XVI had confirmed the miracle involving Sister Marie Simon-Pierre and that John Paul II was to be beatified on 1 May, the Feast of Divine Mercy.[195] 1 May is commemorated in former communist countries, such as Poland, and some Western European countries as May Day, and Pope John Paul II was well-known for his contributions to communism's relatively peaceful demise.[43][51]

On 29 April 2011, Pope John Paul II's coffin was exhumed from the grotto beneath St. Peter's Basilica ahead of his beatification, as tens of thousands of people arrived in Rome for one of the biggest events since his funeral.[196] John Paul II's remains (in a closed coffin) were placed in front of the Basilica's main altar, where believers could pay their respect before and after the beatification mass in St. Peter's Square on 1 May. On 3 May 2011 Blessed Pope John Paul II was given a new resting place in the marble altar in Pier Paolo Cristofari's Chapel of St. Sebastian, which is where Pope Innocent XI was buried. This more prominent location, next to the Chapel of the Pieta, the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament and statues of Popes Pius XI and Pius XII, was intended to allow more pilgrims to view his memorial.

The Polish mint issued a gold 1,000 Polish złoty coin (equivalent to US$350), with the Pope's image to commemorate his beatification.[197]

| “ | It will be a great joy for us when he is officially beatified, but as far as we are concerned he is already a Saint. | ” |

| — Stanisław Cardinal Dziwisz, Archbishop of Kraków[182] | ||

Apologies[edit]

John Paul II apologised to almost every group who had suffered at the hands of the Catholic Church through the years.[37][198] Even before he became Pope, he was a prominent editor and supporter of initiatives like the Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops from 1965. As Pope, he officially made public apologies for over 100 wrongdoings, including:

- The legal process on the Italian scientist and philosopher Galileo Galilei, himself a devout Catholic, around 1633 (31 October 1992).[153][199][200][201]

- Catholics' involvement with the African slave trade (9 August 1993).

- The Church Hierarchy's role in burnings at the stake and the religious wars that followed the Protestant Reformation (May 1995, in the Czech Republic).

- The injustices committed against women, the violation of women's rights and the historical denigration of women (10 July 1995, in a letter to "every woman").

- The inactivity and silence of many Catholics during the Holocaust (see the article Religion in Nazi Germany) (16 March 1998).

| “ | An excuse is worse and more terrible than a lie, for an excuse is a lie guarded.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

Honours and namesakes[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic social teaching |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

Several national and municipal public projects were named in honour of the Pope: the Roma Termini station, was dedicated to Pope John Paul II by a vote of the City Council, the first municipal public object in Rome bearing the name of a non Italian.International airports named after him are John Paul II International Airport Kraków-Balice – one of the principal airports of Poland– and the João Paulo II Airport in the Azores.

| “ | Freedom consists not in doing what we like, but in having the right to do what we ought.[66] | ” |

| — Pope John Paul II | ||

Criticism[edit]

John Paul II was widely criticised for his support of the Opus Dei prelature and the 2002 canonisation of its founder, Josemaría Escrivá, whom he called "the saint of ordinary life."[130][202][203] John Paul II was criticised for protecting movements and religious organisations of the Church, including (Legion of Christ, the Neocatechumenal Way,Schoenstatt, the charismatic movement). The case of Reverend Marcial Maciel, founder of the Legion of Christ was specifically criticised.[130][204]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- For a comprehensive list of books written by and about Pope John Paul II, please see Bibliography of Pope John Paul II

- For other references see Cultural references to Pope John Paul II

- Works by or about Marek69/Pope John Paul II in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

References[edit]

Sources[edit]

- Bertone, Tarcisio. "The Message of Fátima – Tarcisio Bertone". 2000–2009 The Holy See. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - "Cause for Beatification and Canonization of The Servant of God: John Paul II". 2005–2009 Vicariato di Roma – 00184 Roma. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "'Cured' Pope returns to Vatican". 2005–2009 BBC World News. 10 February 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - Domínguez, Juan (4 April 2005). "Pope John Paul II and Communism". Copyright free – Public domain. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Dziwisz, Bishop Stanisław (13 May 2001). "13 May 1981 Conference of Bishop Stanisław Dziwisz For Honorary Doctorate, 13 May 2001 to the Catholic University of Lublin". 2001–2009 L'Osservatore Romano, Editorial and Management Offices, Via del Pellegrino, 00120, Vatican City. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "Frail Pope suffers heart failure". 2005–2009 BBC World News. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - "Half Alive: The Pope vs. his doctors". Time Magazine. 2009 Time Inc. 25 January 1982. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - Kowalska, Saint Maria Faustina (13 April 1989). "The Feast Of Mercy". 1987–2009 Congregation of Marians of the Immaculate Conception, Stockbridge, MA 01263. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "Pope back at Vatican by Easter? It's possible". 2005–2009 msnbc World News. Associated Press. 3 March 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - April 2005 "Pope John Paul II –Home – Editorial". www1.voanews.com. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - "Pope returns to Vatican after op". 2001–2009 BBC News. 13 March 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Sean Gannon (7 April 2006). "Papal fallibility". 2006–2009 Haaretz Daily News, Israel. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - "Stasi Files Implicate KGB in Pope Shooting". 2001–2009 Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - "Pope John Paul II's Final Days". St Anthony Messenger Press. 2005–2009 American Catholic.Org. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - Tchorek, Kamil (2 April 2005). "Cracow lights a candle for its favourite son's last fight". London: 2005–2009 The TimesThe Times online. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Vinci, Alessio (1 April 2005). "Vatican source: Pope given last rites". 2005 Cable News Network LP. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "World awaits word on pope's condition". 2005 Cable News Network LP. 2 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Bibliography[edit]

- Berry, Jason (2004). Vows of Silence: The Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II. New York, London, Toronto, Sydney: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-4441-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw. London: Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-03284-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - de Montfort, St. Louis-Marie Grignion (2007–2009). True Devotion to Mary. Avetine Press 1023 4th Avenue 204 San Diego, CA 92101. ISBN 1-59330-470-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|publisher=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Duffy, Eamon (2006). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes (Third ed.). University Press. ISBN 0-300-11597-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|publisher= - Hebblethwaite, Peter (1995). Pope John Paul II and the Church. London: 1995 Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1556128142.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - John Paul II, Pope (2005). Memory & Identity – Personal Reflections. London: 2006 Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 029785075X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. (2006). Chronicle of the Popes: Trying to Come Full Circle. London: 1997, 2006 Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28608-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Menachery, Prof. George (11 November 1978). "John Paul II Election Surprises". Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Meissen, Randall (2011). Living Miracles: The Spiritual Sons of John Paul the Great. Alpharetta, Ga.: Mission Network. ISBN 978-1933271279.

- Noonan, Peggy (November 2005). John Paul the Great: Remembering a Spiritual Father. New York: Penguin Group (USA). ISBN 9780670037483. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Navarro-Valls, Joaquin (2 April 2005). Il Santo Padre è deceduto questa sera alle ore 21.37 nel Suo appartamento privato (PDF) (in Italian). ‘The Holy Father passed away at 9:37 this evening in his private apartment.’ 2005–2009 The Holy See. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) - O'Connor, Garry (2006). Universal Father: A Life of Pope John Paul II. London: 2005 Publishing. ISBN 0747582416. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher= - Renehan, Edward; Schlesinger, Arthur Meier (INT) (November 2006). Pope John Paul II. Chelsea House. ISBN 9780791092279. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- John Paul II, Pope (2004). Rise, Let Us Be On Our Way. 2004 Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-57781-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Stanley, George E (January 2007). Pope John Paul II: Young Man of the Church. Fitzgerald Books. ISBN 9781424217328. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Szulc, Tadeusz. Pope John Paul II: The Biography. London: 2007 Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group. ISBN 9781416588863.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - The Poynter Institute (1 May 2005). Pope John Paul II: 18 May 1920 – 2 April 2005 (First ed.). St. Petersburg, Florida: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 9780740751103. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Weigel, George (2001). Witness to Hope. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-018793-X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|publisher= - Wojtyła, Karol. Love and Responsibility. London: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-89870-445-6. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Yallop, David (2007). The Power and the Glory. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84529-673-5. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Wilde, Robert. "Pope John Paul II 1920–2005". About.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "John Paul II Biography (1920–2005)". A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "His Holiness John Paul II : Short Biography". Vatican Press Office. 30 June 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Pope John Paul II 1920–2005". CNN. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Roman Woronowycz Kyiv Press Bureau; Pope John Paul II has Ukrainian blood on his mother's side.

- ^ St. Michael Ukrainian Catholic Church in Grand Rapids; Pope John Paul II had relatives on his mother’s side of the family who were Ukrainian Catholics of the Byzantine Rite.

- ^ a b c "Karol Wojtyła (Pope John Paul II) Timeline". Christian Broadcasting Network. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 11. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 25. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Pope John Paul the most revered human being on earth popejohnpaul.com". popejohnpaul.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Kuhiwczak, Piotr (1 January 2007). "A literary Pope". Polish Radio. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ a b Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 60. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 63. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c George Weigel, "Witness to Hope" – HarperCollins Publishers 2001, page 71

- ^ a b c Davies, Norman (2004). Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw. London: Viking Penguin. pp. 253–254. ISBN 0-670-03284-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b George Weigel, "Witness to Hope" – HarperCollins Publishers 2001, pages 71–21

- ^ Norman Davies, Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw – Viking Penguin 2004, pages 253–254

- ^ Witness to Hope, George Weigel, HarperCollins (1999, 2001) ISBN 0-06-018793-X.

- ^ a b "Profile of Edith Zierier (1946)". Voices of the Holocaust. 2000 Paul V. Galvin Library, Illinois Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (2011 [last update]). "John Paul II met with Edith Zierer". dialog.org. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "CNN Live event transcript". CNN. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Genevieve.,"The death of Pope John Paul II: `He saved my life – with tea, bread'", The Independent, 3 April 2005, Retrieved on 17 June 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Roger., " The Polish Seminary Student and the Jewish Girl He Saved", International Herald Tribune, 6 April 2005, Retrieved on 17 June 2007.

- ^ Wiegel, George (2011 [last update]). "Witness_to_Hope_-_The_Biography of Pope Johnpaul II". docstoc.com. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ a b Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 71. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "His Holiness John Paul II, Biography, Pre-Pontificate". Holy See. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ^ a b Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. (2006). Chronicle of the Popes. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-500-28608-6.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ "Pope John Paul II: A Light for the World". United States Council of Catholic Bishops. 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Edward Stourton, "John Paul II: Man of History" – Hodder & Stoughton 2006, page 97

- ^ a b c "John Paul II to Publish First Poetic Work as Pope". ZENIT Innovative Media, Inc. 7 January 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b Landry, Fr. Roger J. (22 April 2005). "God, the Pope and Michelangelo". CatholiCity.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Wojtyła, Karol. Love and Responsibility: 1981

- ^ John Paul II, Pope (2004). Rise, Let Us Be On Our Way. 2004 Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-57781-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 103. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b "Short biography". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Cardinal Deaconry S. Cesareo in Palatio Giga Catholic Information

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "John Paul II: A strong moral vision". CNN. 11 February 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Humanae Vitae". 25 July 1968. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b "A "Foreign" Pope". Time magazine. 30 October 1978. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d "A "Foreign" Pope". Time magazine. 30 October 1978. p. 4. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Stourton, Edward (2006). John Paul II: Man of History. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 171. ISBN 0340908165.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "New Pope Announced". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bottum, Joseph (18 April 2005). "John Paul the Great". Weekly Standard. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ 1978 Year in Review: The Election of Pope John Paul II

- ^ "Events in the Pontificate of John Paul II". 30 June 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. (2006). Chronicle of the Popes: Trying to Come Full Circle. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-500-28608-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ a b c "The Philippines, 1995: Pope dreams of "the Third Millennium of Asia"". AsiaNews. 4 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Manila World Youth Day". Wikipedia. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b The Associated Press (2011 [last update]). "Pope John Paul II Timeline -- CBN.com Spiritual Life". cbn.com. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ a b "1979: Millions cheer as the Pope comes home". from "On This Day, 2 June 1979,". BBC News. 2 June 1979. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d CBC News Online (April 2005). "Pope stared down Communism in homeland –and won". Religion News Service. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "Pope John Paul II and the Fall of the Berlin Wall". 2008 Tejvan Pettinger, Oxford, UK. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "Gorbachev: Pope was 'example to all of us'". CNN. 4 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Thompson, Ginger (30 July 2002). "Pope to Visit a Mexico Divided Over His Teachings". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Irish remember 1979 Papal visit". BBC News. 2 April 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "The Pope's visit to Ireland". CatholicIreland.net. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d "28 May 1982: Pope John Paul II becomes first pontiff to visit Britain". Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Abbott, Elizabeth (1988). Haiti: The Duvalier Years. McGraw Hill Book Company. pp. 260–262. ISBN 0-07-046029-9.

- ^ a b c "Pope pleads for harmony between faiths". BBC News. 24 February 2000. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Reception of His Holiness Catholicos Karekin II". The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church Of Egypt. 27 October 2000. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Plett, Barbara (7 May 2001). "Mosque visit crowns Pope's tour". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Pope John Paul II – Address at Omayyad Mosque of Damascus – 6 May 2001". The Catholic Community Forum and Liturgical Publications of St. Louis, Inc. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "2000: Pope prays for Holocaust forgiveness". BBC News. 26 March 2000. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Klenicki, Rabbi Leon (13 April 2006). "Pope John Paul II's Visit to Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Authority: A Pilgrimage of Prayer, Hope and Reconciliation" (PDF). Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Henneberger, Melinda (21 September 2001). "Pope to Leave for Kazakhstan and Armenia This Weekend". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "BrainyQuote: Pope John Paul II Quotes". BrainyMedia.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "The Holy See: Jubilee Pilgrimages of the Holy Father". Holy See. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Bonacci, Mary Beth (5 May 2005). "The Pope of the Youth". Crisis Magazine. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Bauman, Michelle (2 April 2006). "John Paul II: Pope of the Youth". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ John Paul II, The Meaning of Vocation, ed. by Pedro Lopez. Scepter, 1997.

- ^ Andrea Riccardi. La pace preventiva. Milan: San Paolo 2004.

- ^ a b Kirby, Alex (8 April 2005). "John Paul II and the Anglicans". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Parish Our Lady of the Atonement Catholic Church". 2006,2009 Our Lady of the Atonement. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Dalai Lama mourns John Paul II, "a true spiritual practitioner"". 2005–2009 AsiaNews C.F. 4 March 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Simpson, Victor L. (27 November 2003). "Pope John Paul II Meets With Dalai Lama". WorldWide Religious News. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Brunwasser, Matthew (2 August 2007). "Patriarch Teoctist, 92, Romanian Who Held Out Hand to John Paul II, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Visit of Pope John Paul II to Ukraine". The Institute of Religion and Society, 17 Sventsitskoho Street, Lviv. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Macedonian Press Agency: News in English, 2001-05-04b". The Macedonian Press Agency (Hellenic Resources Network). 4 May 2001. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Stephanopoulos, Nikki (28 January 2008). "Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens". 2008,2009 Associated Press. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (1994). Crossing the Threshold of Hope. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0-679-76561-1.

- ^ "Photo of Pope John Paul II kissing Qur'an". 123muslim.com. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ a b Akin, Jimmy (6 April 2006). "John Paul II kisses the Qur'an". JimmyAkin.org. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Cold Lake Islamic Society – News & updates". coldlakeislamicsociety.ca. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ a b "WQED Pittsburgh: Media-Only Press Room: Papal Concert". 1999–2009 WQED Multimedia. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b "Orchestra to make Vatican history". BBC News. 9 November 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Papal Concert of Reconciliation". 1996–2009 London Philharmonic Choir. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Pitz, Marylynne (8 November 2003). "Pittsburgh Symphony to perform for Pope". 1997–2009 [1] Publishing Co., Inc. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Vatican archives. 2005,2009 Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 1 January 2009.