User:Linga/Great Mosque of Xi'an

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Category:Wikipedia Student Program

| مسجد شيان Great Mosque of Xi'an | |

|---|---|

西安大清真寺 Xī Ān Dà Qīng Zhēn Sì | |

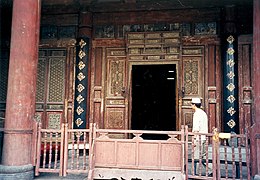

Second courtyard of the Great Mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Province | Shaanxi |

| Leadership | Islamic Association of China |

| Year consecrated | 742 (ancient), 1392 (current form) |

| Location | |

| Location | Xi'an Muslim Quarter |

| Municipality | Xi'an |

| Country | China |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°15′47.9″N 108°56′11.0″E / 34.263306°N 108.936389°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Chinese |

| Site area | 12,300 m2 |

The Great Mosque of Xi'an (Chinese: 西安大清真寺; pinyin: Xī Ān Dà Qīng Zhēn Sì) is the the largest mosque in China.[1][2][3]: 128 It serves as a culture for the sizable ethnic Hui Muslim minority that resides in northwestern China. Although the mosque was allegedly first built in the year 742 AD,[4] it's current form was largely constructed in 1384 AD during Emperor Hongwu's reign of the Ming dynasty[5], as recorded by the Records of Xi'an Municipality (Chinese: 西安府志).

An active place of worship within Xi'an Muslim Quarter,[6] this courtyard complex is also a popular tourist site. It now houses more than twenty buildings in its five courtyards, and covers 12,000 square metres.

Location within Xi'an[edit]

The mosque is also known as the Huajue Mosque (Chinese: 化觉巷清真寺; pinyin: Huà Jué Xiàng Qīng Zhēn Sì),[1][2] for its location on 30 Huajue Lane. It is sometimes called the Great Eastern Mosque (Chinese: 东大寺; pinyin: Dōng Dà Sì), as well, because it is located toward the eastern segments of Xi'an's Xi'an Muslim Quarter (Chinese: 回民街). Sitting on the other side of the Muslim Quarter lies the Daxuexi Alley Mosque (Chinese: 大学习巷清真寺; pinyin: Dà Xué Xí Xiàng Qīng Zhēn Sì),[2] which is consequently known as the "Western Mosque" of Xi'an.

History and Usage[edit]

Original Mosque in Tang and Song Dynasty[edit]

Chang'an, as the cosmopolitan capital of China's Tang Dynasty, had a sizable non-Han merchants and artisans that resided there, many of whom were ethnic Arabs or Iranians that migrated there for trade. Thus, Emperor Xuanzong[7] decreed around the year 742 AD (as Tangmingsi[5], Chinese: 唐明寺) that a place of worship for the Muslim community was to be constructed in the city. Concurrently, mosques for the sizable immigrant population of Quanzhou and Guangzhou were being built at the same time. There is evidence that the early mosque was used during the Song Dynasty due to the presence of an imperial plaque placed in the mosque by the Song government.

Due to the collapse of the Tang dynasty and later the Song dynasty, most of the original mosque constructed in the Tang dynasty did not last until the modern day. The mosque was reconstructed at least four times[7] before taking it's modern shape. At around the 1260s, the then deteriorating mosque was rebuilt by the Yuan government as Huihui Wanshansi (Chinese: 回回万善寺).

The Mongol conquest of China witnessed a large immigration of Muslims into all of China, who were relocated by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty into China to serve as bureaucrats and merchants. The foreign, often Muslim, population brought into China by the Mongol Empire were known in Chinese as People with Coloured Eyes (Chinese: 色目人), many of whom originated from the recently Islamised regions such as Kara-Khanid Xinjiang and Persia. Despite moving into and permanently settling in China, many of the Muslim immigrants and their descendants did not give up their Islamic faith nor "foreign" identity. Many of these new Chinese residences intermarried with the local Han population, forming and consolidating the foundations of the genetically-diverse ethnic Hui population in China[9].

Reconstruction During the Ming Dynasty[edit]

The city of Xi'an, after being destroyed during the collapse of the Tang Dynasty, was reconstructed during the Ming dynasty by 1378 AD. Due to the sizable Muslim population residing in the area, the reconstruction of the original mosque into its contemporary form was patronised by the imperial government during Emperor Hongwu's reign. With a steadily growing Muslim population, the mosque witnessed further additions during the Qing dynasty,[5] which constructed the mosque's front gate, Paifang, and Sebil. Evidences of official patronage of the Mosque is present in the form of recording plaques placed in the Mosque. For instance, a plaque stating the Declaration of the Reconstruction of the Mosque (Chinese:《敕赐重修清真寺碑》) was placed there during 1606 AD[10] at the reign of the Ming government, while another plaque called Declaration to Fix the Mosque (Chinese:《敕修清真寺碑》)[10] was placed there by the Qing government at 1768.

Although the ethnic Hui community were largely able to keep their religious identity, they strongly gravitated and later adopted the mainstream Han Chinese cultural traditions as encouraged by the Ming (and later, Qing) governments[9]. However, certain restrictions on the practice of Islam occurred after Dungan Revolt (1862 - 1877), started due to ethnic and religious tensions between the Hui minority the non-Muslim Han Chinese, which resulted in rioting and mass killings from both sides. After the Dungan Revolt, Muslim freedom of worship was limited, the ritual slaughtering of animals were forbidden, new mosques and the pilgrimage to Mecca was prohibited[9]. Due to the new outward restrictions by the government, the ethnic Hui population, despite assimilating and adopting many aspects of Han Chinese cultural values, started gravitating inwards, with the mosque now serves as a spiritual and ethnic centre for the Hui population. The Great Mosque of Xi'an and its surrounding area thus developed as the center of the Hui population of Xi'an, evidenced by the Xi'an Muslim Quarter centred around it.

In 1956, the government of the People's Republic of China declared the mosque to be a Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the Shaanxi Province Level. However, during the Cultural Revolution, as with practically all other religious facilities, the Mosque was temporarily shut down and converted into a steel factory.[11] However, immediately after Mao Zedong's death in 1976, religious activity resumed and the mosque was later promoted to a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level in 1988. In 1997, it was selected as one of the top 10 tourist attractions in Xi'an.

Modern Usage[edit]

Today, the mosque is widely used as a place of worship by Chinese Muslims, primarily Hui people. The Great Mosque of Xi'an represents the Gedimu (Chinese: 格迪目, Arabic: قديم) tradition of Sunni Islam with the Hanafi jurisdiction, which is the majority jurisprudence that the Hui population follow.[9] Just the main hall of the Great Mosque of Xi’an can accommodate 1,000 people yet today a typical Friday service usually attracts around 100 worshipers.[12] However, non-Muslim tourists are forbidden to enter the prayer hall, although all tourists can freely view the gardens and steles around the prayer hall.

Not only is the mosque a prominent religious site for practicing Muslims, it is also open to tourists to eyewitness the adaptability of Chinese culture and architecture in from an Islamic context. The mosque standing today is not only a religious site to Hui Muslims in the city, but a cultural heritage site to all citizens of Xi'an, reflecting the tremendous ethnic and religious diversity that Tang-era Chang'an hosted.

Architecture[edit]

The Great Mosque of Xi'an is a prominent display of the adaptability of the Islamic faith in the cultural context of Chinese culture. Not only are architectural features of mosques throughout the world present in the Great Mosque of Xi'an, it also contains prominent Chinese architectural and cultural symbols throughout the establishment.

A Mosque in an Chinese Style[edit]

Overall, the mosque's architecture, like the majority of Hui Chinese mosques, combines a traditional Chinese architectural form with Islamic functionality. The mosque is virtually indistinguishable from neighboring religious facilities from other faiths, as Chinese culture genuinely welcomes and encourages the syncretism of foreign cultures into China. The mosque is an excellent example of a foreign religion establishing harmony in a Chinese tradition while maintaining its Islamic functionality. For instance, although traditional Chinese buildings align along a north–south axis in accordance with feng shui (most Chinese religious buildings has its gates open in the north direction), the mosque is directed west towards Mecca,[2] while still conforming to the axes of the imperial city. Furthermore, calligraphy in both Chinese and Perso - Arabic script appears throughout the complex. In order for the Arabic texts to appear more "outwardly Chinese", Islamic scripture and chants traditionally written in Arabic, such as the Shahada, can be seen written in the Sini calligraphy style, which is the style of Arabic calligraphy using Chinese-influenced medium, such as the usage of the Chinese ink brush for writing.

Courtyard[edit]

The mosque is a walled complex of four courtyards, with the central prayer hall located in the fourth courtyard. The first and second courtyards are mostly traditional Chinese gardens, while the third and fourth courtyard is where the main architecture of the mosques are located.[10][5] Each of the courtyards are walled between each other, with certain gateways allowing travel between the courtyards. Most of the architectural features present in the courtyard were constructed during or after the Ming dynasty[3]. However, there are artifacts dating from earlier than the Ming dynasty, such as the plaques on the gates of the second courtyard, which were plaque carvings dated from the Song dynasty (see above figure). Each courtyard contains a central monument, such as a gate, and is lined with greenery as well as subsidiary buildings.

Throughout all of the courtyards lies many Paifangs (Chinese: 牌坊), which are imperially-commissioned arches that commemorate those that have contributed to the government. The multitude of paifangs in the courtyard implies that the Muslim Hui community are treated as equal citizens, in the same way as Han citizens[7]. The first courtyard, for instance, contains a Qing dynasty monumental gate, while the fourth courtyard houses the Phoenix Pavilion, a hexagonal gazebo. Many walls throughout the complex are filled with inscriptions of plants, objects, and text, both in Chinese and Arabic. Stone steles record repairs to the mosque and feature calligraphic works. In the second courtyard, two steles with texts that promote ethnic harmony (for instance, as attached in the figure above, one of the steles draws upon prominent connections between the Islamic faith and Taoism), one of them featuring scripts of the calligrapher Mi Fu of the Song dynasty。

The Xingxinlou (Chinese: 省心楼), or “Examining the Heart Tower,” is a three-story, octagonal pagoda in the third courtyard, which contains many steles dating to as early as the Tang dynasty. The presence of these, often large, steles serve as evidence that the present site of the mosque dates back to at least the Tang dynasty. Despite the usage of this complex as a mosque, the Great Mosque of Xi'an is notible for lacking a minaret. However, some scholars, such as Dr. Nancy Steinhardt from the University of Pennsylvania, speculate that the Xingxin Tower originally served as the mosque's minaret that was previously used for the call to prayer.[13] This courtyard is for visitors to attend prayer services. The fourth courtyard has a bigger prayer hall that can seat more than a thousand people. [14]

The third courtyard is also where many of the maintenance and functionality of the mosque is located. For instance, the mosque's central kitchen, the resident Imam's office, and other governmental administrative departments are located here.[13]

Prayer Hall[edit]

It is believed that the prayer hall was constructed during the Ming dynasty, although significant reconstructions occurred during the Qing era. This is evident as a lot of the pillars in the prayer hall are constructed using traditional Chinese wooden pillars, instead of the more modern brick pillars more prominent in the Qing dynasty. The prayer hall is a monumentally sized timber building with a turquoise hip roof, painted dougong (wooden brackets), a six-pillared portico, and five doors. Contrary to most mosques in predominantly-Muslim countries, the prayer hall does not feature a dome-shaped ceiling, but instead is a traditionally-Chinese, pointy ceiling covered with ceramic decorative tiles, decorated with images of plants and flowers, as Islamic traditions forbids anthropomorphic imageries. The ceiling is raised upon a large stone platform lined with wooden balustrades. The expansive prayer hall consists of three conjoined buildings, set one behind the other. In the deepest part of the prayer hall lies the rear qibla wall, which has wooden carvings of floral and calligraphic designs.[6]

Gallery[edit]

-

“Examining the Heart Tower” in the third courtyard

-

Wahbi Al-Hariri's graphite drawing of the Great Mosque of Xi'an

-

Phoenix Pavilion in the fourth courtyard

-

Facing the prayer hall of the Great Mosque of Xi'an, in the fourth courtyard

-

Entrance to the prayer hall

-

Calligraphy on a plaque in the Great Mosque of Xi'an

See also[edit]

- Islam in China

- Timeline of Islamic history

- List of the oldest mosques in the world

- List of famous mosques

- List of mosques in China

References[edit]

- ^ a b Hagras, Hamada (2017). "An Ancient Mosque in Ningbo, China "Historical and Architectural Study"". Journal of Islamic Architecture. 4 (3): 102–113. doi:10.18860/jia.v4i3.3851.

- ^ a b c d Hagras, Hamada (Summer 2019). "Xi'an Daxuexi Alley Mosque: Historical and Architectural Study". Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies. 9 (1): 97–113. doi:10.21608/ejars.2019.38462.

- ^ a b Liu, Zhiping (1985). Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu [Islamic architecture in China]. Xinjiang Renmin Chubanshe.

- ^ "Great Mosque, Xi'an: One of the Oldest & Best-Protected Mosque in China". www.travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ a b c d Steinhardt, Nancy S. (2015). China's Early Mosques. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748670413.

- ^ a b Hagras, Hamada (2019). "The Ming Court as patron of the Chinese Islamic architecture: The case study of The Daxuexi Mosque in Xi'an". SHEDET. 6 (6): 134–158. doi:10.36816/shedet.006.08.

- ^ a b c 统先, 傅 (2019). 中国回教史. Beijing: 商务印书馆. pp. 33–36.

- ^ 马通. “中国回回民族与伊斯兰教.” In 中国西北伊斯兰教的基本特征, 60-68. Lanzhou: 兰州大学出版社, 1990.

- ^ a b c d 马通. “中国回回民族与伊斯兰教.” In 中国西北伊斯兰教的基本特征, 60-68. Lanzhou: 兰州大学出版社, 1990.

- ^ a b c 路秉杰;张广林. 中国伊斯兰教建筑. Shanghai: 上海三联书店, 2005.

- ^ Chen, Xiaomei. "China's Muslims fear crackdown in ancient city of Xi'an". The Guardian.

- ^ Salahuddin, Iftikhar. "The ancient mosque of X'ian". www.dawn.com. Dawn. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ a b Steinhardt, Nancy S. (2008). "China's Earliest Mosques". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 67 (3): 330–361. doi:10.1525/jsah.2008.67.3.330.

- ^ Tang, Cindy. "Xi'an Great Mosque — the Largest Mosque in China" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|website=ignored (help)

External links[edit]

- Description of the Great Mosque of Xi'an

- Asian Historical Architecture: Great Mosque

- Huajuexiang Mosque in Xian (Masterpiece of Islamic Architecture)

- Great Mosque of Xi'an (islamic-arts.org)

Category:Religious organizations established in the 8th century Category:Mosques in China Category:Buildings and structures in Xi'an Category:Ming dynasty architecture Category:Major National Historical and Cultural Sites in Shaanxi Category:Tourist attractions in Xi'an Xi'an