User:Lfz319/Repatriation and reburial of human remains

The examples and perspective in this deal primarily with the English-speaking world and France and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2023) |

The repatriation and reburial of human remains is a current issue in archaeology and museum management on the holding of human remains. Between the descendant-source community and anthropologists, there are a variety of opinions on whether or not the remains should be repatriated. There are numerous case studies across the globe of human remains that have been or still need to be repatriated.

Perspectives[edit]

The repatriation and reburial of human remains is considered controversial within archaeological ethics [1] Often, descendants and people from the source community of the remains desire their return [2][3][4][5] Meanwhile, Anthropologists, scientists who study the remains for research purposes, may have differing opinions. Some anthropologists feel it is necessary to keep the remains in order to improve the field and historical understanding. [6][7] Others feel that repatriation is necessary in order to respect the descendants. [8]

Descendant and Source Community Perspective[edit]

The descendants and source community of the remains commonly advocate for repatriation. This may be due to human rights and spiritual beliefs. [2][3][4] For example, Henry Atkinson of the Yorta Yorta Nation describes the history that motivates this advocacy. He explains that his ancestors were invaded and massacred by the Europeans. After this, their remains were plundered and "collected like one collects stamps." [2] Finally, the ancestors were shipped away as specimen to be studied. This made the Yorta Yorta people feel subhuman -- like animals and decorative trinkets. Atkinson explains that repatriation will help to soothe the generational pain that resulted from the massacres and collections. [2]

Additionally, there is a repeated theme that descendants have a spiritual connection to their ancestors. Many Indigenous people feel that resting places are sacred and freeing for their ancestors. However, ancestors who are boxed in foreign institutions are trapped and unable to rest. This can cause tremendous distress for their descendants. Some descendants feel that the ancestors can only be free and rest in peace after they are repatriated. [2][3]

This is a similar sentiment within Botswana. Connie Rapoo, a Botswana native, explained the importance of ancestors being repatriated. Rapoo explains that people must return to their home for a sense of kinship and belonging. [4] If they're not returned, the ancestors' souls may wander restlessly. They may even transform into evil spirits who haunt the living. They believe repatriation helps to grant peace to both ancestors and descendants. [4]

Historical trauma[edit]

The argument for repatriation is further complicated by the historical trauma that many Indigenous people experience. Historical trauma refers to the emotional trauma experienced by ancestors that is passed onto generations today. Historically, Indigenous people have experienced massacres and the loss of their children to residential schools. This immense grief is also shared and felt by descendants. [9] Historical trauma is perpetuated by the status of ancestors being boxed away and studied. Some Indigenous people believe that the pain will be alleviated when their ancestors are repatriated and free. [2]

Anthropologists/Scientist Perspective[edit]

Anthropologists have divided opinions on supporting or rejecting repatriation.

Anti-Repatriation[edit]

Some anthropologists feel that repatriation will harm anthropological research and understanding. For example, Elizabeth Weiss and James W. Springer believe that repatriation is the loss of collections, and thereby the "loss of data." [6] This is due to the nature of Western science and epistemology. To improve scientific accuracy, biological anthropologists test new methods and retest old methods on collections. Weiss and Springer describe Indigenous remains as the most abundant and significant resource to the field. They believe that reburial prevents the improvement and legitimacy of anthropological methods. [6]

According to some anthropologists, this in turn prevents many important findings. Studying human remains may reveal information on human pre-history. It helps anthropologists learn how humans evolved and came to be. [7] Additionally, the study of human remains reveals numerous characteristics about ancient populations. It may reveal population's health status, diseases, labor activities, and violence they experienced. Anthropology may identify cultural practices such as the cranial modification. It can also help populations today. Specifically, anthropologists have found signs of early arthritis on ancient remains. They believe this identification is beneficial for the early detection of arthritis in people today. [7]

Some anthropologists feel that these discoveries will be lost with the reburial of human remains. [6][7]

Pro-Repatriation[edit]

Not all anthropologists are anti-repatriation. Rather, some feel that repatriation is an ethical necessity that the field has been neglecting. Sian Halcrow et al. explains that anthropology has a history of racist double standards.[8] Specifically, White remains within archaeological and disaster cases are reburied in coffins. Meanwhile, Indigenous and non-White remains are infamously boxed and studied. She notes that the unethical sourcing and study of remains without permission is considered a civil rights violation. Halcrow et al. proposes that the repatriation is the bare minimum request to have one's remains treated the same as others. [8]

Some anthropologists view repatriation -- not as a privilege -- but as a human right that had been refused to people of color for too long. They don't view repatriation as the loss or downfall of anthropology. Rather, they feel that repatriation is the start of anthropology moving toward more ethical methods. [8]

Case Studies[edit]

Canada[edit]

During the 1800s, Canada established numerous residential schools for Indigenous youth. This was an act of cultural assimilation and genocide, where many of the children died and were buried at these schools. In the 21st century, these mass are being discovered and repatriated. Two of the most well-known mass graves includes those at the Kamloops Indian Residential School (over 200 Indigenous children buried) and the Saskatchewan Residential School (over 700 Indigenous children buried). Canada is working on searching for and repatriating these graves. [10]

Spain[edit]

El Negro[edit]

The name "El Negro" refers to a dead African man who was taxidermized and displayed in the Darder Museum in Banyoles, Spain. His initial grave had been dug up around 1830. He was then taxidermized and dressed up with fur clothing and a spear. "El Negro" was sold to the Darder Museum and on display for over a century. It wasn't until 1992 when Banyoles was hosting the summer Olympics that people complained of the displayed and taxidermized human remains. [11]

In 2000, "El Negro" was repatriated to Botswana, which was believed to be his country of origin. Numerous Botswanans had gathered in the airport to greet "El Negro." However, there was controversy in the status and shipment of his remains. First, "El Negro" had arrived in a box, rather than a coffin. Botswanans felt this was dehumanizing. Second, "El Negro" was not returned as the whole body. Rather, only a stripped skull was sent to Botswana. The Spanish had skinned his body, claiming his skin and artifacts to be their property. Numerous Botswanas felt severely disrespected and offended by the objectification of "El Negro." [11][4]

United Kingdom[edit]

Sarah Baartman[edit]

Sarah Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman from Cape Town, South Africa, in the early 1800s. She was taken to Europe and advertised as a sexual "freak" for entertainment. Here was she known as the "Hottentot Venus." She died in 1815 and was dissected. Baartman's genitalia, brain, and skeleton were displayed in the Musee de l'Homme in Paris until repatriation to South Africa in 2002. [4]

United States[edit]

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain cultural items such as human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, etc. to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations.[12][13][14]

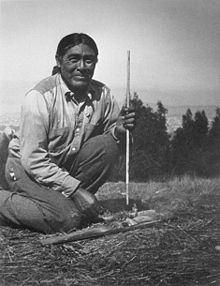

Ishi[edit]

Ishi was the last survivor of the Yahi Tribe in the early 1900s. He lived amongst and was studied by anthropologists for the rest of his life. During this time, he would tell stories of his tribe, give archery demonstrations, be studied on his language. Ishi fell ill and died from Tuberculosis in 1916. [15]

Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe. [15]

Kennewick Man[edit]

The Kennewick Man is the name generally given to the skeletal remains of a prehistoric Paleoamerican man found on a bank of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, United States, on 28 July 1996.[16][17] This became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the United States Army Corps of Engineers, scientists, the Umatilla people and other Native American tribes who claimed ownership of the remains.[18]

The remains of Kennewick Man were finally removed from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on 17 February 2017. The following day, more than 200 members of five Columbia Plateau tribes were present at a burial of the remains.[19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Scarre and Scarre (2006). The ethics of archaeology : philosophical perspectives on archaeological practice, p. 206-208. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-54942-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Atkinson, Henry (2010). "The Meanings and Values of Repatriation". In Turnbull, Paul; Pickering, Michael (eds.). The long way home: the meanings and values of repatriation. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-1-84545-958-1.

- ^ a b c Cubillo, Franchesca (2010). "Repatriating Our Ancestors: Who Will Speak for the Dead?". In Turnbull, Paul; Pickering, Michael (eds.). The long way home: the meanings and values of repatriation. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 20–26. ISBN 978-1-84545-958-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Rapoo, Connie (June 2011). "'Just give us the bones!': theatres of African diasporic returns". Critical Arts. 25 (2): 132–149. doi:10.1080/02560046.2011.569057. ISSN 0256-0046.

- ^ Cressida, Fforde (2002). The Dead and their Possessions : Repatriation in Principle, Policy and Practice. London: Routledge. pp. 245–255. ISBN 978-0-203-16577-5.

- ^ a b c d Weiss, Elizabeth; Springer, James (September 2020). Repatriation and erasing the past. University of Florida Press. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-1-68340-223-7. OCLC 1253398847.

- ^ a b c d Landau, Patricia (2000). Mihesuah, Devon (ed.). Repatriation Reader: who owns American Indian remains?. London: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 74–94. ISBN 0-8032-8264-8.

- ^ a b c d Halcrow, Siân; Aranui, Amber; Halmhofer, Stephanie; Heppner, Annalisa; Johnson, Norma; Killgrove, Kristina; Schug, Gwen Robbins (26 November 2021). "Moving beyond Weiss and Springer's Repatriation and Erasing the Past: Indigenous values, relationships, and research". International Journal of Cultural Property. 28 (2): 211–220. doi:10.1017/S0940739121000229. ISSN 0940-7391.

- ^ Brave Heart, Maria Yellow Horse (February 2010). "The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention". Smith College Studies in Social Work. 68 (3): 287–304 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Zabriskie, Julia (April 2023). "Searching for Indigenous Truth: Exploring a Restorative Justice Approach to Redress Abuse at American Indian Boarding Schools". Boston College Law Review. 64 (4): 1039–1076.

- ^ a b Cressida, Fforde (2002). The Dead and their Possessions : Repatriation in Principle, Policy and Practice. London: Routledge. pp. 245–255. ISBN 978-0-203-16577-5.

- ^ "FAQ". NAGPRA. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Cook, Myles Russell; Russell, Lynette (1 December 2016). "Museums are returning indigenous human remains but progress on repatriating objects is slow". The Conversation. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ a b Scheper-Hughes, Nancy (February 2001). "Ishi's brain, Ishi's ashes: Anthropology and genocide". Anthropology Today. 17 (1): 12–18.

- ^ Preston, Douglas (September 2014). "The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets", Smithsonian. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Stafford, Thomas W. (2014). "Chronology of the Kennewick Man skeleton (chapter 5)". In Douglas W. Owsley; Richard L. Jantz (eds.). Kennewick Man, The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-62349-200-7.

- ^ Minthorn, Armand (September 1996). "Ancient One / Kennewick Man • Human Remains Should Be Reburied". Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Paulus, Kristi (20 February 2017). "Kennewick Man finally buried by local tribes". keprtv.com. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- "International repatriation of human remains of indigenous peoples". International Council of Museums. 8 August 2018.

This is an extract of the article 'National and international legislation' by Lynda Knowles, originally published in The Future of Natural History Museums, edited by Eric Dorfman.

- Aboriginal remains repatriation (Australia)

- Book reviews of Scarre & Scarre and Vitelli and Colwell