User:Kiwibirb97/sandbox

Rufa Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)[edit]

The Rufa Red Knot is a subspecies of the Red Knot, a medium-sized shorebird whose breeding plumage is a striking shade of red. This robin-size shorebird is a master of long-distance aviation, migrating over 9,000 miles across nearly the full latitude gradient of the Western Hemisphere every spring. It is most closely related to two other subspecies, C. c. islandica and C. c. roselaari[1]. It is among one of the best studied shorebirds in the world, and is closely monitored to maintain its population size in the face of present threats both human and environmental.

Distribution and Migration[edit]

| Kiwibirb97/sandbox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Calidris canutus rufa, breeding plumage | |

| |

| Non-breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Calidris |

| Species: | C. c. rufa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Calidris canutus rufa | |

| |

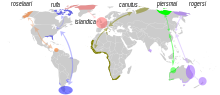

| Distribution and migration routes of the six subspecies of the red knot; Rufa Red Knot is marked in blue | |

Historical and Present Range[edit]

Annually, the Rufa Red Knot migrates between its breeding ground in the high Arctic tundra of North America and any of their four different wintering regions: the Southeast United States/Caribbean, the Northwest Gulf of Mexico, the Northern coast of South America, and as far south as Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, and Brazil[3][4]. Not much is known or understood about the range and habitat use during the breeding season, when the species is distributed sparsely across the Canadian Arctic. Recent studies on environmental characteristics suggest that the Rufa Red Knots were found to prefer sparsely vegetated tundra on sedimentary, primarily limestone, bedrock at elevations below 150 m[5]. In their wintering regions, again, not much is known about their distribution or range since it appears that they tend to concentrate in large numbers in relatively few sites[6].

Critical Habitat[edit]

On their way north each spring, a significant part of the Northern Hemisphere’s Rufa population migrates through Delaware Bay, NJ. This is where the birds stop during their migration from South America to feed on energy-rich eggs laid by horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus). These eggs provide a rich, easily digestible food source for the migrating birds. Research suggests that the crabs have been so over-harvested that the Red Knots have become deprived of much-needed fuel[7].

Description and anatomy[edit]

At 9 to 10 inches long (or 23-25 centimeters long), the red knot is is a large, bulky sandpiper with a short, straight, black bill and speckled grey-brown back. During the breeding season, the legs are dark brown to black, and the throat, breast and belly are a characteristic russet color that ranges from salmon-red to brick-red. Males are generally brighter shades of red, with a more distinct line through the eye. In winter, when not breeding, both sexes look alike—plain gray above and dirty white below with faint, dark streaking. Young birds look similar to winter adults but usually have a faint salmon-pink or peach wash on their chest.The rufa subspecies shows a lighter red breast than the Red Knot roselaari and islandica subspecies[8][9].

Behavior[edit]

Diet and Feeding[edit]

Rufa Red Knots feed on invertebrates, especially small clams, mussels, and snails, but also crustaceans, and marine worms. Their most important food source, however, are horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) eggs. The eggs provide a rich, easily digestible food source for the migrating birds. Because it provides abundant horseshoe crab eggs, Delaware Bay is the single most important spring stopover habitat during spring migration, supporting an estimated 50 to 80 percent of all migrating Rufa Red Knots each year. Mussel beds and small clams on New Jersey's southern Atlantic coast are also an important food source for migrating knots, in both spring and fall. On the breeding grounds knots mainly eat insects[10][11].

Breeding[edit]

Rufa Red Knots breed on islands in the Canadian Arctic, with hotspots for breeding on the Southampton and Coats Islands. The males will fly high above their territory calling until a female joins them. They then display on the ground with their wings held up, and females decide whether to mate. They nest primarily on sparsely vegetated areas, building nests in prostrate shrub or sedge patches. However have also been seen nesting on coarse glacial deposits. Rufa Red Knot nests are shallow scrapes on the ground lined with moss, lichen, and other vegetation. Their nests are built a short distance away from bodies of fresh water and wetlands, so that they can easily forage for food, but not so close as to attract predators, such as falcons and owls.[12] The Rufa Red Knot will lay 3-4 pale olive green eggs with brown spots. These eggs are incubated by both parents, which take turns for 21-22 days before hatching. The newly hatched birds are tended to by both parents, but the females leave before the young are able to fly. The young birds forage for their own food, and are able to fly after 18-20 days, at which point they become independent. [13]

Life History[edit]

Immediately after hatching, Rufa Red Knots are small downy birds. They can feed themselves, eating insects near their nests for the next 18-20 days, at which point they have grown their flight feathers and can fly. At this point the birds become independent and leave the nest to fend for themselves.[14] After their initial growth, the largest change in the Rufa Red Knot's physiology takes place before and during their long migration from South America to the Arctic. During this time, the flight muscles of the birds get larger and their leg muscles get smaller. In addition, the birds will decrease the mass of their stomach and gizzard, while increasing their fat mass by over 50 percent. These changes allow the birds to fly long distances more easily. This shrinking of the gizzard also means that the birds must eat fewer hard foods, like the shelled crustaceans they eat during the winter, and rely on supplies of soft horseshoe crab eggs during their migration. They arrive at staging areas in their migrations; places where crab eggs or other food sources are common, very thin, and eat a massive amount of readily available eggs, increasing their weight by 10 percent each day, until they have doubled in weight at each stop. [15]

Status and Conservation[edit]

Historical and Present Population Size[edit]

Rufa Red Knot populations were heavily hunted in the early 20th century in North America, as part of commercial hunting for sport and food. Knots are still hunted in parts of the Caribbean and South America. However, in the United States, Knot hunting ended with the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, and historical writings show the birds largely recovered [16]. But in the 20th century, a population decline occurred due primarily to reduced food availability from overharvesting of the horseshoe crab. Rufa Red Knot numbers in Tierra del Fuego (winter) and Delaware Bay (spring) declined about 75 percent from the 1980s to the 2000s. Red Knot numbers appear to have stabilized in the past few years, but at low levels relative to earlier decades [17]. A recent 2012 study estimates that the Rufa population in 2012 was likely about 42,000 [18].

IUCN listing[edit]

The Rufa Red Knot is currently listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN, with a decreasing population trend, though the continuing decline is unknown. It had been cited as Least Concern four times from 2004 to 2012, and had been cited as Unknown before that. Since 2015, it has been assessed in 2016, 2017, and 2018, receiving a Near Threatened listing each time. These assessments were conducted by BirdLife International. [2]

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Listing History[edit]

The Rufa Red Knot was listed as Threatened by the Endangered Species Act on January 12 of 2015. It is listed wherever found, meaning that any populations are all considered threatened. It appeared on an annual review of candidates for listing of endangered or threatened every year from 2006 to 2012. From 2004 to 2008 a series of 4 petitions were filed by a number of organizations to list the Rufa Red Knot as endangered or threatened. From 2013 to 2014 it was proposed to be listed as threatened three times, but it did not receive a federal listing by the ESA until its threatened status in 2015. There are currently no Species Status Assessments by the ESA. [19]

Human Impact and Major Threats[edit]

The Rufa Red Knot faces many threats along the Western Hemisphere. Many are driven by climate change which is causing rising sea levels, increasing storms, and changing food and habitat availability. Additional threats include development, human disturbance, predation and hunting, among others[20]. Several studies have been done looking at human disturbance's effect on the Rufa Red Knot. They have shown that the Rufa are disturbed by the presence of people, and return to the beach less frequently and at longer intervals than gulls that also compete for the crab eggs. Experiments with closure of a beach indicated that when people are present knots move to a protected fenced-off area, but when it is closed they use the entire beach for foraging, and, voluntary closure of a beach is not as effective as mandatory closure in protecting foraging shorebirds. However, dogs cause more disturbance than people. Additionally, the expansion of aquaculture in intertidal areas may impact birds and other organisms using these habitats, leading to questions of sustainability of both aquaculture and functioning estuarine ecosystems. Recent studies have shown that the Rufa Red Knot avoids oyster racks while both foraging and roosting, suggesting that caution should be used before placing racks in areas used for foraging by Red Knots, particularly their critical habitat along the Delaware Bay.[21].

Conservation Efforts[edit]

The horseshoe crab harvest in the Delaware Bay area is now managed specifically for the protection of the Rufa Red Knot. By 1998, the Atlantic State Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) adopted the first Fishery Management Plan for horseshoe crabs, and the horseshoe crab bait harvest has been controlled since 2013[22].

Knot populations appear to have stabilized in recent years, though at low levels. Listing of the Rufa Red Knot in 2015 on the ESA brought new protections [23]. In areas along the U.S. coast, partners are managing beaches to minimize disturbance and to reduce interference from gulls and peregrines. In addition, biologists in the Carolinas and Florida are improving beach habitat by controlling invasive plants.

In South America, several key Rufa Red Knot sites are becoming shorebird reserves, and regional efforts include the protection of Rufa Red Knot habitats in urban development plans. Hunting regulations, voluntary hunting restrictions, increased hunter education efforts, no-shoot shorebird refuges and sustainable harvest models are also underway to address hunting in various countries[24].

References[edit]

- ^ Buehler, Deborah; Baker, Allan; Piersma, Theunis (2006). "Reconstructing palaeoflyways of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene Red Knot Calidris canutus" (PDF). Ardea: 485–498. S2CID 31016225.

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2015). "Calidris canutus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ Manrique, Katie (February 2020). "Effect of Arctic snow cover on red knot, Calidris canutus, population size". BIOS. 91 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1893/BIOS-D-18-00019. ISSN 0005-3155. S2CID 211228458.

- ^ Lathrop, Richard G.; Niles, Lawrence; Smith, Paul; Peck, Mark; Dey, Amanda; Sacatelli, Rachael; Bognar, John (2018-08-01). "Mapping and modeling the breeding habitat of the Western Atlantic Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa) at local and regional scalesMapeo y modelado del hábitat reproductivo de Calidris canutus rufa a escalas local y regionalModeling Red Knot nesting habitat". The Condor. 120 (3): 650–665. doi:10.1650/CONDOR-17-247.1. ISSN 0010-5422. S2CID 91382600.

- ^ Harrington, B.A.; Morrison, R.I.G. "NOTES ON THE WINTERING AREAS OF RED KNOT Caiidris canutus rufa IN ARGENTINA SOUTH AMERICA" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin.

- ^ Munro, Margaret (2017-01-05). "What's killing the world's shorebirds?". Nature News. 541 (7635): 16–20. doi:10.1038/541016a. PMID 28054629. S2CID 4448329.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ "Red Knot - New Jersey Field Office - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ "Red Knot - New Jersey Field Office - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ Lathrop, Richard G.; Niles, Lawrence; Smith, Paul; Peck, Mark; Dey, Amanda; Sacatelli, Rachel; Bognar, John (1 August 2018). "Mapping and modeling the breeding habitat of the Western Atlantic Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa) at local and regional scales". The Condor. 120 (3): 650–665. doi:10.1650/CONDOR-17-247.1. S2CID 91382600.

- ^ Kaufman, Ken (13 November 2014). "Red Knot Calidris canutus". Audubon. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ Kaufman, Ken (13 November 2014). "Red Knot Calidris canutus". Audubon. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ "Red knot Calidris canutus rufa" (PDF). US Fish and Wildlife Service. Northeast Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ "Red knot BW fact sheet" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andres, B.A., Smith, P.A., Morrison, R.I.G., Gratto-Trevor, C.L., Brown, S.C. & Friis, C.A. 2012. Population estimates of North American shorebirds, 2012. Wader Study Group Bull. 119(3): 178–194.

- ^ "Red knot (Calidris canutus rufa)". ECOS Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ^ Burger, Joanna; Niles, Lawrence J. (2017-07-15). "Habitat use by Red Knots (Calidris canutus rufa): Experiments with oyster racks and reefs on the beach and intertidal of Delaware Bay, New Jersey". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 194: 109–117. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2017.04.025. ISSN 0272-7714.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ^ "Northeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service". fws.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Protects the Rufa Red Knot as Threatened Under Endangered Species Act" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External Links[edit]

- National Geographic Red Knot Article (2013)

- The Rufa Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa) – US Fish and Wildlife Service

- Red knot photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Red Knot Audubon Field Guide

- Red Knot – North Dakota Game and Fish Dept.

- Red Knot – National Wildlife Federation

- Rufa Red Knot Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision

- "A Bird, a Crab and a Shared Fight to Survive" NY Times Article on Red Knot & Horseshoe Crabs

- NY Species Status Assessment (2014)

- Red Knot – Birds of Nebraska Online