User:Kayla.mcgeorge/sandbox

From the Adolescence Page[edit]

Romance and sexual activity[edit]

Romantic relationships tend to increase in prevalence throughout adolescence. By age 15, 53% of adolescents have had a romantic relationship that lasted at least one month over the course of the previous 18 months.[1] In a 2008 study conducted by YouGov for Channel 4, 20% of 14−17-year-olds surveyed revealed that they had their first sexual experience at 13 or under in the United Kingdom.[2] A 2002 American study found that those aged 15–44 reported that the average age of first sexual intercourse was 17.0 for males and 17.3 for females.[3] The typical duration of relationships increases throughout the teenage years as well. This constant increase in the likelihood of a long-term relationship can be explained by sexual maturation and the development of cognitive skills necessary to maintain a romantic bond (e.g. caregiving, appropriate attachment), although these skills are not strongly developed until late adolescence.[4] Long-term relationships allow adolescents to gain the skills necessary for high-quality relationships later in life[5] and develop feelings of self-worth. Overall, positive romantic relationships among adolescents can result in long-term benefits. High-quality romantic relationships are associated with higher commitment in early adulthood[6] and are positively associated with self-esteem, self-confidence, and social competence.[7][8]

Adolescence marks a time of sexual maturation, which manifests in social interactions as well. While adolescents may engage in casual sexual encounters (often referred to as hookups), most sexual experience during this period of development takes place within romantic relationships.[9] Kissing, hand holding, and hugging signify satisfaction and commitment. Among young adolescents, "heavy" sexual activity, marked by genital stimulation, is often associated with violence, depression, and poor relationship quality.[10][11] This effect does not hold true for sexual activity in late adolescence that takes place within a romantic relationship.[12]

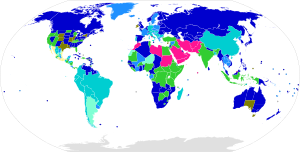

The age of consent to sexual activity varies widely among international jurisdictions, ranging from 12 to 21 years.[13] Adolescents often date within their demographic in regards to race, ethnicity, popularity, and physical attractiveness.[14] However, there are traits in which certain individuals, particularly adolescent girls, seek diversity. While most adolescents date people approximately their own age, boys typically date partners the same age or younger; girls typically date partners the same age or older.[1]

Some researchers are now focusing on learning about how adolescents view their own relationships and sexuality; they want to move away from a research point of view that focuses on the problems associated with adolescent sexuality. Lucia O’Sullivan and her colleagues found that there weren’t any significant gender differences in the relationship events adolescent boys and girls from grades 7-12 reported.[15] Most teens said they had kissed their partners, held hands with them, thought of themselves as being a couple and told people they were in a relationship. This means that private thoughts about the relationship as well as public recognition of the relationship were both important to the adolescents in the sample. Sexual events (such as sexual touching, sexual intercourse) were less common than romantic events (holding hands) and social events (being with one’s partner in a group setting). The researchers state that these results mean that researchers should focus more on the positive aspects of adolescents and their social and romantic interactions rather than put most of their focus on sexual behavior and its consequences.[15]

Dating violence is fairly prevalent within adolescent relationships. When surveyed, 10-45% of adolescents reported having experiencing physical violence in the context of a relationship while one-third to a quarter of adolescents reported having experiencing psychological aggression. This reported aggression includes hitting, throwing things, or slaps, although most of this physical aggression does not result in a medical visit. Physical aggression in relationships tends to decline from high school through college and young adulthood. By their early twenties, many fewer romantic couple engage in physical aggression, and aggressors tend to be much more deviant.[16] In heterosexual couples, there is no significant difference between the rates of male and female aggressors, a surprising finding considering the common assumption that males are more aggressive overall.[17][18][19] Despite these jarring statistics, nurturant parenting style is associated with lower rates of relationship violence.[20]

In contemporary society, adolescents also face some risks as their sexuality begins to transform. Whilst some of these such as emotional distress (fear of abuse or exploitation) and sexually transmitted diseases (including HIV/AIDS) are not necessarily inherent to adolescence, others such as pregnancy (through non-use or failure of contraceptives) are seen as social problems in most western societies.

In terms of sexual identity, while all sexual orientations found in adults are also represented among adolescents, statistically the suicide rate amongst LGBT adolescents is up to four times higher than that of their heterosexual peers [21] According to anthropologist Margaret Mead, the turmoil found in adolescence in Western society has a cultural rather than a physical cause; they reported that societies where young women engaged in free sexual activity had no such adolescent turmoil.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Carver K., Joyner K., Udry J.R. (2003). National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In Adolescent Romantic Relationships and Sexual Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications, 291–329.

- ^ "Teen Sex Survey". Channel 4. 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ http://www.newstrategist.com/productdetails/Sex.SamplePgs.pdf Seventeen Is the Average Age at First Sexual Intercourse, American Sexual Behavior, p.4-5

- ^ Allen, J., & Land, D. (1999). Attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment theory and research. New York: Guilford Press.

- ^ Madsen S., Collins W. A. (2005). Differential predictions of young adult romantic relationships from transitory vs. longer romantic experiences during adolescence. Presented at Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development, Atlanta, GA.

- ^ Seiffge-Krenke I., Lang J. (2002). Forming and maintaining romantic relations from early adolescence to young adulthood: evidence of a developmental sequence. Presented at Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 19th, New Orleans, LA.

- ^ Pearce M. J., Boergers J., Prinstein M.J., (2002). Adolescent obesity, overt and relational peer victimization, and romantic relationships. Obesity Research, 10, 386–93.

- ^ Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J., Siebenbruner, J., & Collins, W.A. (2004). A prospective study of intraindividual and peer influences on adolescents’ heterosexual romantic and sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 381-394.

- ^ Manning, W., Longmore, M., & Giordano, P. (2000). The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives, 32(3), 104-110.

- ^ Welsh D. P., Haugen P. T.,Widman L., Darling N., Grello C. M. (2005). Kissing is good: a developmental investigation of sexuality in adolescent romantic couples. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 2, 32–41.

- ^ Williams T., Connolly J., Cribbie R. (2008). Light and heavy heterosexual activities of young Canadian adolescents: normative patterns and differential predictors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 145–72.

- ^ Grello C. M., Welsh D. P., Harper MS, Dickson J. (2003). Dating and sexual relationship trajectories and adolescent functioning. Adolescent & Family Health, 3, 103–12.

- ^ Ageofconsent.com

- ^ Simon V. A., Aikins J. W., Prinstein M. J. (2008). Romantic partner selection and socialization during early adolescence. Child Dev. In press.

- ^ a b O’Sullivan, L. F., Mantsun, M. Cheng, K. Harris, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2007). I wanna hold your hand: The progression of social, romantic and sexual events in adolescent relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(2), 100-107

- ^ Archer J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 651–80

- ^ Halpern, C., Oslak, S., Young, M., Martin, S., & Kupper, L. (2001). Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1679-1685.

- ^ Halpern, C., Young, M., Waller, M., Martin, S., & Kupper, L. (2004). Prevalence of partner violence in same-sex romantic and sexual relationships in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 124-131.

- ^ Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652.

- ^ Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652.

- ^ http://gaylife.about.com/od/gayteens/a/gaysuicide.htm

Category:Adolescence Category:Educational psychology

From the Adolescent Sexuality Page[edit]

Adolescent sexuality refers to sexual feelings, behavior and development in adolescents and is a stage of human sexuality. Sexuality and sexual desire usually begin to intensify along with the onset of puberty at which time sexuality often becomes a vital aspect of teenagers' lives.[1] The expression of sexual desire and behavior of adolescents is influenced by their culture's norms and mores, their sexual orientation, their family values, their culture, social engineering, social taboos and the issues of social control such as age of consent laws.

In humans, mature sexual desire usually begins to appear with the onset of puberty. Sexual expression can take the form of masturbation or sex with a partner. Sexual interests among adolescents, as among adults, can vary greatly. Sexual activity in general is associated with various risks including unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS. The risks are elevated for young adolescents because their brains are not neurally mature; several brain regions in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex and in the hypothalamus important for self control, delayed gratification, and risk analysis and appreciation are not fully mature. The creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens, and the brain is not fully mature until age 25.[2] Partially because of this, young adolescents are generally less equipped than adults to make sound decisions and anticipate consequences of sexual behavior.[3]

Adolescent sexual behavior[edit]

Prevalence of sexual intercourse in 15-year-olds[edit]

| Country | Boys (%) | Girls (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 21.7 | 17.9 |

| Canada | 24.1 | 23.9 |

| Croatia | 21.9 | 8.3 |

| England | 34.9 | 39.9 |

| Estonia | 18.8 | 14.1 |

| Finland | 23.1 | 32.7 |

| Belgium | 24.6 | 23 |

| France | 25.1 | 17.7 |

| Greece | 32.5 | 9.5 |

| Hungary | 25 | 16.3 |

| Israel | 31 | 8.2 |

| Latvia | 19.2 | 12.4 |

| Lithuania | 24.4 | 9.2 |

| Macedonia | 34.2 | 2.7 |

| Netherlands | 23.3 | 20.5 |

| Poland | 20.5 | 9.3 |

| Portugal | 29.2 | 19.1 |

| Scotland | 32.1 | 34.1 |

| Slovenia | 45.2 | 23.1 |

| Spain | 17.2 | 13.9 |

| Sweden | 24.6 | 29.9 |

| Switzerland | 24.1 | 20.3 |

| Ukraine | 47.1 | 24 |

| Wales | 27.3 | 38.5 |

In 2002, an international survey was conducted, with the aim of studying the prevalence of sexual intercourse in adolescents. The researchers surveyed 33,943 students aged 15, from 24 countries, completed a self-administered, anonymous, classroom survey, consisting of a standard questionnaire, developed by the HBSC (Health Behaviour in School- aged Children) international research network. The survey revealed that the majority of the students were still virgins (they had no experience of sexual intercourse), and, among those who were sexually active, the majority (82%) used contraception.[4]

Loss of virginity[edit]

Conceptions about loss of virginity[edit]

Researchers found that adolescents generally think of their loss of virginity in one of the following ways: as a gift, as a stigma and as a normal step in development. Researchers found that girls generally think of virginity as a gift, while boys think of virginity as a stigma (meaning they often seek to cover up the fact that they are virgins) [5]. In interviews, girls said that they viewed giving someone their virginity like giving them a very special gift. Because of this, they often expected something in return such as increased emotional intimacy with their partners or the virginity of their partner. However, they often felt disempowered because of this; they often did not feel like they actually received what they expected in return and this made them feel like they had less power in their relationship. They felt that they had given something up and didn’t feel like this action was recognized. [5]. Thinking of virginity as a stigma disempowered many boys because they felt deeply shamed and often tried to hide the fact that they were virgins from their partners which for some resulted in their partners teasing them about their limited sexual techniques and criticizing them. The girls who viewed virginity as a stigma did not feel this shame. Even though they privately thought of virginity was a stigma, these girls believed that society valued their virginity because of the stereotype that women are sexually passive. This, they said, made it easier for them to lose their virginities once they wanted to because they felt society had a more positive view on female virgins and that this may have made them them sexually attractive. Thinking of losing virginity as part of a natural developmental process resulted in no power imbalances in the genders because these individuals felt less affected by other people and were more in control of their sexual experience [5].

Motivations for loss of virginity[edit]

Studies found that adolescent girls were less likely to state that they had ever had sex than adolescent boys. However, among boys and girls who had experienced sexual intercourse, the proportion of girls and boys who had recently had sex and were regularly sexually active was the same [6] Researchers think that fewer girls say they have ever had sex because girls viewed teenage parenthood as more of a problem than boys and were generally more restricted in their sexual attitudes; they were more likely than boys to believe that they would be able to control their sexual urges. Girls had a more negative association in how being sexually active could affect their future goals. In general, girls said they felt less pressure from peers to begin having sex, while boys reported feeling more pressure. [6]

When asked about abstinence (the choice to not engage in sex), many girls reported they felt conflicted by what society was telling them to do; they were trying to balance maintaining a good reputation with trying to maintain a romantic relationship and wanting to behave in adult like ways. On the other hand, boys viewed having sex as social capital; many boys believed that their male peers who were abstinent wouldn’t as easily climb the social ladder as sexually active boys. Some boys said that for them, the risks that may come from having sex were not as bad as the social risks that could come from remaining abstinent. [7]

Adolescent sexual functioning: gender similarities and differences[edit]

Lucia O’Sullivan and her colleagues studied adolescent sexual functioning; they compared an adolescent sample with an adult sample and found no significant differences between them. Desire, satisfaction and sexual functioning were generally high among their sample of participants (aged 17-21). Additionally, no significant gender differences were found in the prevalence of sexual dysfunction. [8] In terms of problems with sexual functioning mentioned by participants in this study, the most common problems listed for males was experiencing anxiety about performing sexually (81.4%) and premature ejaculation (74.4%). Other common problems included issues becoming erect and difficulties with ejaculation. Generally, most problems were not experienced on a chronic basis. Common problems for girls included difficulties with sexual climax (orgasm) (86.7%), not feeling sexually interested during a sexual situation (81.2%), unsatisfactory vaginal lubrication (75.8%) anxiety about performing sexually (75.8%) and painful intercourse (25.8%). Most problems listed by the girls were not persistent problems. However, inability to experience orgasm seemed to be an issue that was persistent for some participants. [8]

The authors detected four trends during their interviews: sexual pleasure increased with the amount of sexual experience the participants had; those who had experienced sexual difficulties typically were sex-avoidant; some participants continued to engage in regular sexual activity even if they had low interest and lastly, many experienced pain when engaging in sexual activity if they experienced low arousal. [8]

Another study found that it was not uncommon for adolescent girls in relationships to report they felt little desire to engage in sexual activity when they were in relationships. However, many girls engaged in sexual activity even if they did not desire it, in order to avoid what they think might place strains on their relationships. [9] The researcher states that this may be because of society's pressure on girls to be "good girls"; the pressure to be "good" may make adolescent girls think they are not supposed to feel desire like boys do. Even when girls said they did feel sexual desire, they said that they felt like they were not supposed to, and often tried to cover up their feelings. This is an example of how societal expectations about gender can impact adolescent sexual functioning [9].

Same-gender attractions among adolescents[edit]

Adolescent girls and boys who are attracted to others of the same gender are strongly affected by their surroundings in that adolescents often decide to express their sexualities or keep them secret depending on certain factors in their societies. These factors affect girls and boys differently. If girl’s schools and religions are against same sex attractions, they pose the greatest obstacles to girls who experience same sex attractions. These factors were not listed as affecting boys as much. The researchers suggest that maybe this is because not only are some religions against same-gender attraction, but they also encourage traditional roles for women and do not believe that women can carry out these roles as lesbians. Schools affect girls more than boys maybe because strong emphasis is placed on girls to date boys, and many school activities place high importance on heterosexuality (such as cheerleading). On the other hand, having a high number of male heterosexual friends inhibits many gay boys from expressing their sexual orientation because heterosexual boys are more likely to be homophobic than girls[10]. Additionally, the idea of not conforming to typical male gender roles inhibited many boys from openly expressing their same-sex attraction. The worry of conforming to gender roles didn’t inhibit girls from expressing their same-gender preferences as much, because society is generally more flexible about their gender expression. [10]

Researchers such as Lisa Diamond are interested in how some adolescents depart from the socially constructed norms of gender and sexuality. She found that some girls, when faced with the option of choosing “heretosexual”, “same-sex attracted” or “bisexual”, preferred not to choose a label because their feelings do not fit into any of those categories [11].

In the United States[edit]

Prevalence of sexual activity[edit]

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2007 47.8% of U.S. high school students reported having ever had sexual intercourse. This number has shown a downward trend since 1991, when the figure was 54.1%.[12] According to a survey commissioned by NBC News and People magazine, 87% of 13- to 16-year-olds report having never had sexual intercourse, and 73% report having not been sexually intimate at all. Three quarters of these respondents say they have not because they feel they are too young, and just as many say they have made a conscious decision not to.[13]

Increasing rates of oral sex among teens have been reported. However a study released in 2008 by the Guttmacher Institute found that, while oral sex is slightly more common than vaginal sex among teens, the prevalence of oral sex among teen opposite-sex partners has held steady for the last decade.[14] According to the study, slightly more than half (55%) of 15– to 19-year-olds have engaged in heterosexual oral sex, 50% have engaged in vaginal sex and 11% have had anal sex.

The CDC also tracks the percentage of students who say they used drugs or alcohol before sex. While this risk behavior increased between 1991 and 2001, the trend has been declining since then.[12] In 2007, 22.5% of high school students reported this risk behavior, down from 25.6% in 2001.[12]

The same survey found while only 27% of 13- to 16-year-olds had been involved in intimate or sexual activity, 8% had had a casual sexual relationship,[13] which has been described by one journalist as a "profound shift in the culture of high school dating and sex".[15] In his book, Why Gender Matters, researcher Leonard Sax states that teenage sexual encounters are increasingly taking place outside the context of romantic relationships, in purely sexual "hookups".[16]

In 2002, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health reported a "dramatic trend toward the early initiation of sex".[17] According to the American Academy of Pediatrics "early sexual intercourse among American adolescents represents a major public health problem. Although early sexual activity may be caused by a variety of factors, the media are believed to play a significant role. U.S. teens rank the media second only to school sex education programs as a leading source of information about sex".[18]

Among sexually active 15- to 19-year-olds, 83% of females and 91% of males reported using at least one method of birth control during last intercourse.[19] The most common methods of contraception are condoms and birth control pills. In 2007, 61.5% of high school students reported using a condom the last time they had sexual intercourse, up from 46% in 1991.[12]

Risk factors[edit]

The U.S. teen pregnancy rate is higher than in many other developed countries.[20] After declining steadily since 1991, the teen pregnancy rate rose 3% in 2006, to 41.9 births per 1,000. This followed a 14-year downward trend in which the teen birth rate fell by 34% from its 1991 peak of 61.8 births per 1,000.[21]

Public health officials express concerns that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and risky behaviors that include "anything but intercourse" are "rampant" among teens.[22] Of the 18.9 million new cases of STIs each year, 9.1 million (48%) occur among 15- to 24-year-olds, even though this age group represents only one-quarter of the sexually active population.[20] According to a 2008 study by the CDC, an estimated 1 in 4 teen girls has at least one STI at any given time.[23]

Most teenagers (70%) reported that they received some or a lot of information about sex and sexual relationships from their parents. Other sources of information included friends at 53%, school, also at 53%, TV and movies at 51% and magazines at 34%. School and magazines were said to be used as sources of information more by girls than by boys, and sexually active teens were more likely to cite their friends and partners as information sources.[13]

Historical perspectives on sexuality and sexual health[edit]

Changes in the expression of adolescent sexuality in the United States find their origins in the sexual revolution and was the focus of the "culture wars". The U.S. federal government policy under George W. Bush emphasized sexual abstinence or chastity, particularly in sex education with a focus on abstinence-only sex education rather than the harm reduction approach of the safe sex focus. It extended this approach to foreign policy, using the threat to withdraw foreign aid to press NGO's into ending condom education and distribution in third-world countries. There is ongoing debate between those advocating comprehensive, medically accurate sex education and those who regard only abstinence-based education as accord "the values held by most Americans".[22]

In Britain[edit]

In 2006, a survey conducted by The Observer showed that most adolescents in Britain were waiting longer to have sexual intercourse than they were only a few years earlier. In 2002, 32% of teens were having sex before the age of 16; in 2006 it was only 20%. The average age a teen lost his/her virginity was 17.13 years in 2002; in 2006, it was 17.44 years on average for girls and 18.06 for boys. The most notable drop among teens who reported having sex was 14- and 15-year-olds.[24]

A 2008 survey conducted by YouGov for Channel 4 showed that 40% of all 14- to 17-year-olds are sexually active, 74% of sexually active 14- to 17-year-olds have had a sexual experience under the age of consent, and 6% of teens would wait until marriage before having sex.[25]

Of Western European countries, Britain has been stated to have a teenage pregnancy rate as high as America's, and sexually transmitted infections in Britain are on the increase.[26] One in nine sexually active teens has chlamydia and 790,000 teens have sexually transmitted infections. In 2006 The Independent newspaper reported that the biggest rise in sexually transmitted infections was in syphilis, which rose by more than 20 per cent, while increases were also seen in cases of genital warts and herpes.[27]

In Canada[edit]

One group of Canadian researchers found a relationship between self esteem and sexual activity. They found that students, especially girls, who were verbally abused by teachers or rejected by their peers were more likely than other students to have sex by the end of the Grade 7. The researchers speculate that low self esteem increases the likelihood of sexual activity: "low self-esteem seemed to explain the link between peer rejection and early sex. Girls with a poor self-image may see sex as a way to become 'popular', according to the researchers".[28]

In India[edit]

In India there is growing evidence that adolescents are becoming more sexually active outside of marriage. It is feared that this will lead to an increase in spread of HIV/AIDS among adolescents, increase the number of unwanted pregnancies and abortions, and give rise to conflict between contemporary social values. Adolescents have relatively poor access to health care and education. With cultural norms opposing extramarital sexual behavior "these implications may acquire threatening dimensions for the society and the nation".[29]

- Motivation and frequency

Sexual relationships outside marriage are not uncommon among teenage boys and girls in India. By far, the best predictor of whether or not a girl would be having sex is if her friends were engaging in the same activities. For those girls whose friends were having a physical relationship with a boy, 84.4% were engaging in the same behavior. Only 24.8% of girls whose friends were not having a physical relationship had one themselves. In urban areas, 25.2% of girls have had intercourse and in rural areas 20.9% have. Better indicators of whether or not girls were having sex were their employment and school status. Girls who were not attending school were 14.2% (17.4% v. 31.6%) more likely and girls who were employed were 14.4%(36.0% v. 21.6%) more likely to be having sex.[29]

In the Indian sociocultural milieu girls have less access to parental love, schools, opportunities for self development and freedom of movement than boys do. It has been argued that they may rebel against this lack of access or seek out affection through physical relationships with boys. While the data reflects trends to support this theory, it is inconclusive.[29] The freedom to communicate with adolescent boys was restricted for girls regardless of whether they lived in an urban or rural setting, and regardless of whether they went to school or not. More urban girls than rural girls discussed sex with their friends. Those who did not may have felt "the subject of sexuality in itself is considered an 'adult issue' and a taboo or it may be that some respondents were wary of revealing such personal information."[30]

- Contraceptive use

Among Indian girls, "misconceptions about sex, sexuality and sexual health were large. However, adolescents having sex relationships were somewhat better informed about the sources of spread of STDs and HIV/AIDS."[29] While 40.0% of sexually active girls were aware that condoms could help prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy, only 10.5% used a condom during the last time they had intercourse.[29]

Media influence[edit]

Modern media contains more sexual messages than was true in the past and the effects on teen sexual behavior remain relatively unknown.[31] Only 9% of the sex scenes on 1,300 of cable network programming discusses and deals with the negative consequences of sexual behavior.[32] The Internet may further provide adolescents with poor information on health issues, sexuality, and sexual violence.[33]

A study on examining sexual messages in popular TV shows found that 2 out of 3 programs contained sexually related actions. 1 out of 15 shows included scenes sexual intercourse itself. Shows featured a variety of sexual messages, including characters talking about when they wanted to have sex and how to use sex to keep a relationship alive. Researchers believe that adolescents can use these messages as well as the sexual actions they see on TV in their own sexual lives.[34]

The results of a study by Deborah Tolman and her colleagues indicated that adolescent exposure to sexuality on television in general does not directly affect their sexual behaviors, rather it is the type of message they view that has the most impact[35]. What really affected adolescents was what type of societal gender stereotypes they were seeing enacted in the sexual scenes they saw on TV.

What made girls feel they had less control over their sexuality was when they saw women attracting men by objectifying themselves and when they observed men behaving as if commitment wasn’t important. The consequences of this, is that these girls may believe that they should present themselves as sexual objects, comply to the demands of boys and not listening to their own wants and needs. On the other hand, girls who saw women on TV who refuted men’s sexual advances usually felt more comfortable talking about their own sexual needs in their sexual experiences. They were more able to set sexual limits, therefore held more control over their sexual experiences. Findings for boys were less clear; those who saw dominant and aggressive men actually had less sexual experiences. Perhaps there were less effects on boys because this Heterosexual Script does not affect them as deeply as it does girls. [35]

Teenage pregnancy[edit]

Adolescent girls become fertile following the menarche (first menstrual period), which occurs in the United States at an average age of 12.5, although it can vary widely between different girls. After menarche, sexual intercourse (especially without contraception) can lead to pregnancy. The pregnant teenager may then miscarry, have an abortion, or carry the child to full term.

Pregnant teenagers face many of the same obstetrics issues as women in their 20s and 30s. However, there are additional medical concerns for younger mothers, particularly those under 15 and those living in developing countries; for example, obstetric fistula is a particular issue for very young mothers in poorer regions.[36] For mothers between 15 and 19, risks are associated more with socioeconomic factors than with the biological effects of age.[37] However, research has shown that the risk of low birth weight is connected to the biological age itself, as it was observed in teen births even after controlling for other risk factors (such as utilisation of antenatal care etc.).[38][39]

Worldwide, rates of teenage births range widely. For example, sub-Saharan Africa has a high proportion of teenage mothers whereas industrialized Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan have very low rates.[40] Teenage pregnancy in developed countries is usually outside of marriage, and carries a social stigma; teenage mothers and their children in developed countries show lower educational levels, higher rates of poverty, and other poorer "life outcomes" compared with older mothers and their children.[41] In the developing world, teenage pregnancy is usually within marriage and does not carry such a stigma.[42]

Legal aspects of adolescent sexual activity[edit]

Sexual conduct between adults and adolescents younger than the local age of consent is illegal, and in some Islamic countries any kind of sexual activity outside marriage is prohibited. In many jurisdictions, sexual intercourse between adolescents with a close age difference is not prohibited. Around the world, the average age-of-consent is 16,[43] but this varies from being age 13 in Spain, age 16 across Canada, and age 16-18 in the United States. In some jurisdictions, the age-of-consent for homosexual acts may be different from that for heterosexual acts. The age-of-consent in a particular jurisdiction is typically the same as the age of majority or several years younger. The age at which one can legally marry is also sometimes different from the legal age-of-consent.

Sexual relations with a person under the age-of-consent are generally a criminal offense in the jurisdiction in which the crime was committed, with punishments ranging from token fines to life imprisonment. Many different terms exist for the charges laid and include statutory rape, illegal carnal knowledge, or corruption of a minor. In some cases, sexual activity with someone above the legal age-of-consent but beneath the age of majority can be punishable under laws against contributing to the delinquency of a minor.[citation needed]

Society's influence on adolescent sexuality[edit]

Social constructionist perspective[edit]

The Social constructionist perspective (see social constructionism for a general definition) on adolescent sexuality examines how power, culture, meaning and gender interact to affect the sexualities of adolescents. [44] This perspective is closely tied to feminist and queer theory. Those who believe in the social constructionist perspective state that the current meanings most people in our society tie to female and male sexuality are actually a social construction to keep Heterosexual and privileged people in power [45].

Researchers interested in exploring adolescent sexuality using this perspective typically investigates how gender, race, culture, socioeconomic status and sexual orientation affect how adolescent understand their own sexuality.[46] An example of how gender affects sexuality is when young adolescent girls state that they believe sex is a method used to maintain relationships when boys are emotionally unavailable. Because they are girls, they believe they ought to engage in sexual behavior in order to please their boyfriends. [47]

Developmental feminist perspective[edit]

The developmental feminist perspective is closely tied to the social constructionist perspective. It is specifically interested in how society's gender norms affect adolescent development, especially for girls. For example, some researchers on the topic hold the view that adolescent girls are still strongly affected by gender roles imposed on them by society and that this in turn affects their sexuality and sexual behavior. Deborah Tolman is an advocate for this viewpoint and states that societal pressures to be “good” cause girls to pay more attention to what they think others expect of them than looking within themselves to understand their own sexuality. Tolman states that young girls learn to objectify their own bodies and end up thinking of themselves as objects of desire. This causes them to often see their own bodies as others see it, which causes them to feel a sense of detachment from their bodies and their sexualities. Tolman calls this a process of disembodiment. This process leaves young girls unassertive about their own sexual desires and needs because they focus so much on what other people expect of them rather than on what they feel inside. [48]

Another way gender roles affect adolescent sexuality is thought the sexual double standard. This double standard occurs when others judge women for engaging in premarital sex and for embracing their sexualities, while men are rewarded for the same behavior. [49] It is a double standard because the genders are behaving similarly, but are being judged differently for their actions because of their gender. An example of this can be seen in Tolman’s research when she interviews girls about their experiences with their sexualities. In Tolman’s interviews, girls who sought sex because they desired it felt like they had to cover it up in order (for example, they blamed their sexual behavior on drinking) to not be judged by others in their school. They were afraid of being viewed negatively for enjoying their sexuality. Many girls were thus trying to make their own solutions (like blaming their sexual behavior on something else or silencing their own desires and choosing to not engage in sexual behavior) to a problem that is actually caused by power imbalances between the genders within our societies. [48] Other research showed that girls were tired of being judged for their sexual behavior because of their gender. However, even these girls were strongly affected by societal gender roles and rarely talked about their own desires and instead talked about how “being ready” (rather than experiencing desire) would determine their sexual encounters. [49]

O’Sullivan and her colleagues assessed 180 girls between the ages of 12 and 14 on their perceptions on what their first sexual encounters would be like; many girls reported feeling negative emotions towards sex before their first time. The researchers think this is because adolescent girls are taught that society views adolescent pre-marital sex in negative terms. When they reported positive feelings, the most commonly listed one was feeling attractive. This shows how many girls objectify their own bodies and often think about this before they think of their own sexual desires and needs [50]

Researchers found that having an older sibling, especially an older brother, affected how girls viewed sex and sexuality. [51] Girls with older brothers held more traditional views about sexuality and said they were less interested in seeking sex, as well as less interested responding to the sexual advances of boys compared with girls with no older siblings. Researchers believe this is because older siblings model gender roles, so girls with older siblings (especially brothers) may have more traditional views of what society says girls and boys should be like; girls with older brothers may believe that sexual intercourse is mostly for having children, rather than for gaining sexual pleasure. This traditional view can inhibit them from focusing on their own sexualities and desires, and may keep them constrained to society’s prescribed gender roles.[51]

Social learning and the sexual self-concept[edit]

Developing a sexual self-concept is an important developmental step during adolescence. This is when adolescents try to make sense and organize their sexual experiences so that they understand the structures and underlying motivations for their sexual behavior. [52] This sexual self-concept helps adolescents organize their past experiences, but also gives them information to draw on for their current and future sexual thoughts and experiences. Sexual self-concept affects sexual behavior for both men and women, but it also affects relationship development for women. [52] Development of one’s sexual self-concept can occur even before sexual experiences begin. [53] An important part of sexual self-concept is sexual esteem, which includes how one evaluates their sexuality (including their thoughts, emotions and sexual activities). [54] Another aspect is sexual anxiety; this includes one’s negative evaluations of sex and sexuality. [54] Sexual self-concept is not only developed from sexual experiences; both girls and boys can learn from a variety of social interactions such as their family, sexual education programs, depictions in the media and from their friends and peers. [55] [52]. Girls with a positive self-schema are more likely to be liberal in their attitudes about sex, are more likely to view themselves as passionate and open to sexual experience and are more likely to rate sexual experiences as positive. Their views towards relationships show that they place high importance on romance, love and intimacy. Girls who have a more negative view often say they feel self conscious about their sexuality and view sexual encounters more negatively. The sexual self concept of girls with more negative views are highly influenced by other people; those of girls who hold more positive views are less so. [52]

Boys are less willing to state they have negative feelings about sex than girls when they describe their sexual self-schemas [56] Boys are not divided into positive and negative sexual self-concepts; they are divided into schematic and non-schematic (a schema is a cluster of ideas about a process or aspect of the world; see schema). Boys who are sexually schematic are more sexually experienced, have higher levels of sexual arousal, and are more able to experience romantic feelings. Boys who are not schematic have fewer sexual partners, a smaller range of sexual experiences and are much less likely than schematic men to be in a romantic relationship [56]

When comparing the sexual self-concepts of adolescent girls and boys, researchers found that boys experienced lower sexual self-esteem and higher sexual anxiety. The boys stated they were less able to refuse or resist sex at a greater rate than the girls reported having difficulty with this. The authors state that this may be because society places so much emphasis on teaching girls how to be resistant towards sex, that boys don’t learn these skills and are less able to use them when they want to say no to sex. They also explain how society’s stereotype that boys are always ready to desire sex and be aroused may contribute to the fact that many boys may not feel comfortable resisting sex, because it is something society tells them they should want [57] Because society expects adolescent boys to be assertive, dominant and in control, they are limited in how they feel it is appropriate to act within a romantic relationship. Many boys feel lower self-esteem when they can’t attain these hyper-masculine ideals that society says they should. Additionally, there is not much guidance on how boys should act within relationships and many boys do not know how to retain their masculinity while being authentic and reciprocating affection in their relationships. This difficult dilemma is called the double-edged sword of masculinity by some researchers. [58].

Hensel and colleagues conducted a study with 387 female participants between the ages of 14 and 17 and found that as the girls got older (and learned more about their sexual self-concept), they experienced less anxiety, greater comfort with sexuality and experienced more instances of sexual activity. [55] Additionally, across the four years (from 14-17), sexual self-esteem increased, and sexual anxiety lessened. The researchers stated that this may indicate that the more sexual experiences the adolescent girls have had, the more confidence they hold in their sexual behavior and sexuality. Additionally, it may mean that for girls who have not yet had intercourse, they become more confident and ready to participate in an encounter for the first time [59] Researchers state that these patterns indicate that adolescent sexual behavior is not at all sporadic and impulsive, rather that it is strongly affected by the adolescent girls’ sexual self-concept and changes and expands through time. [59]

Sex education[edit]

Sex education, also called "Sexuality Education" or informally "Sex Ed" is a broad term used to describe education about human sexual anatomy, sexual reproduction, sexual intercourse, human sexual behavior, and other aspects of sexuality, such as body image, sexual orientation, dating, and relationships. Common avenues for sex education are parents, caregivers, friends, school programs, religious groups, popular media, and public health campaigns.

Sexual education in different countries varies. For example, in France sex education has been part of school curricula since 1973. Schools are expected to provide 30 to 40 hours of sex education, and pass out condoms to students in grades eight and nine. In January, 2000, the French government launched an information campaign on contraception with TV and radio spots and the distribution of five million leaflets on contraception to high school students.[60]

In Germany, sex education has been part of school curricula since 1970. Since 1992 sex education is by law a governmental duty.[61] A survey by the World Health Organization concerning the habits of European teenagers in 2006 revealed that German teenagers care about contraception. The birth rate among 15 to 19-year-olds is 11.7 per 1000 population, compared to 2.9 per 1000 population in Korea, and 55.6 per 1000 population in US.[62]

In Asia the state of sex education programs are at various stages of development. Indonesia, Mongolia, South Korea and Sri Lanka have a systematic policy framework for teaching about sex within schools. Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand have assessed adolescent reproductive health needs with a view to developing adolescent-specific training, messages and materials. India has programs that specifically aim at school children at the age group of nine to sixteen years. These are included as subjects in the curriculum and generally involved open and frank interaction with the teachers. Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan have no coordinated sex education programs.[63]

According to SIECUS, the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, in most families, parents are the primary sex educators of their adolescents. They found 93% of adults they surveyed support sexuality education in high school and 84% support it in junior high school.[64] In fact, 88% of parents of junior high school students and 80% of parents of high school students believe that sex education in school makes it easier for them to talk to their adolescents about sex.[65] Also, 92% of adolescents report that they want both to talk to their parents about sex and to have comprehensive in-school sex education.[citation needed]

Almost all U.S. students receive some form of sex education at least once between grades 7 and 12; many schools begin addressing some topics as early as grade 5 or 6.[66] However, what students learn varies widely, because curriculum decisions are quite decentralized.[67] Two main forms of sex education are taught in American schools: comprehensive and abstinence-only. A 2002 study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 58% of secondary school principals describe their sex education curriculum as comprehensive, while 34% said their school's main message was abstinence-only.[67] The difference between these two approaches, and their impact on teen behavior, remains a controversial subject in the U.S.[68][69] Some studies have shown abstinence-only programs to have no positive effects.[70] Other studies have shown specific programs to result in more than 2/3 of students maintaining that they will remain abstinent until marriage months after completing such a program;[71] such virginity pledges, however, are statistically ineffective,[72][73] and over 95% of Americans do, in fact, have sex before marriage.[74]

Some educators hold the view that sexuality is equated with violence. These educators think that not talking about sexuality will decrease the rate of adolescent sexuality. However, not having access to sexual education has been found to have negative effects upon students, especially groups such as adolescent girls who come from low-income families. Not receiving appropriate sexual health education increases teenage pregnancy, sexual victimization and high school dropout rates. Researchers state that it is important to educate students about all aspects of sexuality and sexual health to reduce the risk of these issues. [75]

The view that sexuality is victimization teaches girls to be careful of being sexually victimized and taken advantage of. Educators who hold this perspective encourage sexual education, but focus on teaching girls how to say no, teaching them of the risks of being victims and educate them about risks and diseases of being sexually active. This perspective teaches adolescents that boys are predators and that girls are victims of sexual victimization. Researchers state that this perspective does not address the existence of desire within girls, does not address the societal variables that influence sexual violence and teaches girls to view sex as dangerous only before marriage (however, in reality, sexual violence can be very prevalent within marriages too). [75]

Another perspective includes the idea that sexuality is individual morality; this encourages girls to make their own decisions, as long as their decision is to say no to sex before marriage. This education encourages self control and chastity. [75]

Lastly, the sexual education perspective of the discourse of desire is very rare in U.S. high schools. [44] This perspective encourages adolescents to learn more about their desires, gaining pleasure and feeling confident in their sexualities. Researchers state that this view would empower girls because it would place less emphasis on them as the victims and encourage them to have more control over their sexuality. [75]

Research on how gender stereotypes affect adolescent sexuality is important because researchers believe it can show sexual health educators how they can improve their programming to more accurately attend to the needs of adolescents. For example, studies have shown how the social constructed idea that girls are “supposed to” not be interested in sex have actually made it more difficult for girls to have their voices heard when they want to have safer sex [76] [77]. At the same time, sexual educators continuously tell girls to make choices that will lead them to safer sex, but don’t always tell them ‘how’ they should go about doing this. Instances such as these show the difficulties that can arise from not exploring how society’s perspective of gender and sexuality affect adolescent sexuality. [78].

In the U.S., 431 schools in fifty districts (0.35% of all districts and 2.2% of all high schools nationwide) have established school-based condom availability programs. These programs involve condom distribution, condom-use education and information, peer support, sex and STDs education within the curriculum, and involvement of parents, staff, partnerships, and health care providers. Studies have shown that condom availability programs in high schools may lower the risk of HIV, STDs, and teen pregnancy. In all schools, condom use increased while sexual behaviour remained the same among high school students following the implementation of condom availability programs.[79][80][81][82]

See also[edit]

- Age disparity in sexual relationships

- Child sexuality

- Family planning

- Adolescent sexuality in the United States

- Condom

References[edit]

- ^ Ponton, Lynn (2000). The Sex Lives of Teenagers. New York: Dutton. p. 2. ISBN 0-452-28260-8.

- ^ Casey, B. J., Getz, S., & Galvan, A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review, 28(1), 62-77.

- ^ John R. Chapman (2000). "Adolescent sex and mass media: a developmental approach". Adolescence. Winter (140): 799–811. PMID 11214217.

- ^ Godeau E, Nic Gabhainn S, Vignes C, Ross J, Boyce W, Todd J (January 2008). "Contraceptive use by 15-year-old students at their last sexual intercourse: results from 24 countries". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.8. PMID 18180415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Carpenter, L. M. (2002). Gender and the meaning and experience of virginity loss in the contemporary United States. Gender and Society, 16, 345–365.

- ^ a b De Gaston, J. F., Weed, S. (1996). Understanding gender differences in adolescent sexuality. Adolescence, 31, (121), 217-231.

- ^ Ott, M. A., Pfeiffer, E. J.,& Fortenberry, J. D. (2006). Perceptions of Sexual Abstinence among High-Risk Early and Middle Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 192-198.

- ^ a b c O’Sullivan, Lucia & Majerovich, JoAnn (2008). Difficulties with sexual functioning in a sample of male and female late adolescent and young adult university students. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 17 (3), 109-121.

- ^ a b Tolman, D. L. (2001). Female adolescent sexuality: An argument for a developmental perspective on the new view of women’s sexual problems. Women and Therapy, 42(1-2), 195- 209.

- ^ a b Waldner, Haugrud, L. D., & Macgruder, B. (1996).Homosexual identity expression among lesbian and gay adolescents: An analysis of perceived structural associations. Youth Society, 27, 313-333.

- ^ Diamond, L. (2000). Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual-minority women over a two-year period. Developmental Psychology, 36, 241-250.

- ^ a b c d "Trends in the Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors" (PDF). The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 1991-2007. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-02. [dead link]

- ^ a b c Katie Couric (2005). "Nearly 3 in 10 young teens 'sexually active'". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ Duberstein Lindberg, Laura. "Non-coital sexual activities among adolescents" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Alexandra Hall. "The Mating Habits of the Suburban High School Teenager". Boston Magazine (May 2003).

- ^ Sax, M.D., Ph.D, Leonard (2005). Why Gender Matters. Doubleday. p. 132. ISBN 0-385-51073-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sieving RE, Oliphant JA, Blum RW (December 2002). "Adolescent sexual behavior and sexual health". Pediatr Rev. 23 (12): 407–16. doi:10.1542/pir.23.12.407. PMID 12456893. S2CID 245091714.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education, American Academy of Child and Adolescent psychiatry, American Psychological Association (January 2001). "Sexuality, contraception, and the media. Committee on Public Education". Pediatrics. 107 (1): 191–4. doi:10.1542/peds.107.1.191. PMID 11134460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sexual Health Statistics for Teenagers and Young Adults in the United States" (PDF). Kaiser Family Foundation. September 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "Facts on American Teens' Sexual and Reproductive Health". Guttmacher Institute. September 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Teen Birth Rate Rises for First Time in 15 Years" (Press release). National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-12-05. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ a b Anna Mulrine. "Risky Business" (PDF). U.S. News & World Report (May 27, 2002).

- ^ "Nationally Representative CDC Study Finds 1 in 4 Teenage Girls Has a Sexually Transmitted Disease" (Press release). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008-03-11. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Denis Campbell (January 22, 2006). "No sex please until we're at least 17 years old, we're British". The Observer.

- ^ "Teen Sex Survey". Channel 4. 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Christine Webber, psychotherapist and Dr David Delvin (2005). "Talking to pre-adolescent children about sex". Broaching the subject. Net Doctor. Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Jonathan Thompson (November 12, 2006). "New safe sex ads target teens 'on the pull'". The Independent.

- ^ Peer rejection tied to early sex in pre-teens

- ^ a b c d e R.S.Goya, Indian Institute of Health Management Research, Jaipur, India. "Socio-psychological Constructs of Premarital Sex Behavior among Adolescent Girls in India" (pdf). Abstract. Princeton University. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "india girls" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Dhoundiyal Manju & Venkatesh Renuka (2006). "Knowledge regarding human sexuality among adolescent girls". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 73 (8): 743. doi:10.1007/BF02898460. PMID 16936373. S2CID 31606897.

- ^ Brown JD (February 2002). "Mass media influences on sexuality". J Sex Res. 39 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1080/00224490209552118. PMID 12476255. S2CID 6342646.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Pawlowski,Cheryl.,PH d. Glued to the Tube., Sourcebooks, INC., Naperville,Il.2000.

- ^ Subrahmanyam, Kaveri., Greenfield, Patricia,M., Tynes, Brendesha. The Internet Influences Teen Sexual Attitudes. Teen Sexuality:Opposing Viewpoints 2006.

- ^ Brown, J. D. (2002). Mass media influences on sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 39(1), 42-45.

- ^ a b Tolman, D. L., Kim, L. L., Schoolar, D., & Sorsoli, C. L. (2007). Rethinking the Associations between Television Viewing and Adolescent Sexuality Development: Bringing Gender into Focus. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 84.e9 – 84.e1.

- ^ Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries

- ^ Makinson C (1985). "The health consequences of teenage fertility". Fam Plann Perspect. 17 (3): 132–9. doi:10.2307/2135024. JSTOR 2135024. PMID 2431924.

- ^ Loto, OM; Ezechi, OC; Kalu, BKE; Loto, Anthonia B; Ezechi, Lilian O; Ogunniyi, SO (2004). "Poor obstetric performance of teenagers: is it age- or quality of care-related?". Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 24 (4): 395–398. doi:10.1080/01443610410001685529. PMID 15203579. S2CID 43808921.

- ^ Abalkhail, BA (1995). "Adolescent pregnancy: Are there biological barriers for pregnancy outcomes?". The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 70 (5–6): 609–25. PMID 17214178.

- ^ Indicator: Births per 1000 women (15-19 ys) – 2002 UNFPA, State of World Population 2003, Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. (2002). "Not Just Another Single Issue: Teen Pregnancy Prevention's Link to Other Critical Social Issues" (PDF). (58.5 KB). Retrieved May 27, 2006.

- ^ Population Council (January 2006). "Unexplored Elements of Adolescence in the Developing World". Population Briefs. 12 (1).

- ^ http://www.avert.org/age-of-consent.htm

- ^ a b Tolman, D. L., & Diamond, L. M. (2001). Desegregating sexuality research: Cultural and biological perspectives on gender and desire. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12, 33-74.

- ^ Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1993). Theorizing heterosexuality. In S. Wilkinson & C. Kitzinger, (Eds.), Heterosexuality: A feminism and psychology reader (pp. 1-32). London: Sage Publications

- ^ Tolman, D. L., Striepe, M. I., & Harmon, T. (2003). Gender Matters: Constructing a Model of Adolescent Sexual Health. Journal of sex research, 40(1), 4-12.

- ^ O’Sullivan, L., & Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L. (1996). African-American and Latina inner-city girls’ reports of romantic and sexual development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(2): 221–238.

- ^ a b Tolman, D. L. (2001). Female adolescent sexuality: An argument for a developmental perspective on the new view of women’s sexual problems. Women and Therapy, 42(1-2), 195- 209.

- ^ a b Jackson, S. M., & Cram, F. (2003). Disrupting the sexual double standard: young women’s talk about heterosexuality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 113–127.

- ^ O’Sullivan, L., & Hear, K. D. (2008). Predicting first intercourse among urban early adolescent girls: The role of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 22(1), 168-2008, 22 (1), 168-179.

- ^ a b Kornreich, J. L., Hearn, K. D., Rodriguez, G., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2003). Sibling Influence, Gender Roles, and the Sexual Socialization of Unban Early Adolescent Girls. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 101-110.

- ^ a b c d Andersen, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 67, 1079–1100.

- ^ Butler, T. H., Miller, K. S., Holtgrave, D. R., Forehand, R., & Long, N. (2006). Stages of sexual readiness and six-month stage progression among AfricanAmerican pre-teens. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 378–386.

- ^ a b Snell, W. E. (1998). The multidimensional sexual self-concept questionnaire. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.),Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 521–524). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ^ a b Hensel, D. J., Fortenberry, J. D., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Orr, D. P. (2011). The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 675-684.

- ^ a b Andersen, B. L., Cyranowski, J. M., & Espindle, D. (1999). Men’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology., 76, 645–661.

- ^ S., Dekhtyar, O., Cupp, P., & Anderman, E. (2008). Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: a possible clue to promoting sexual health? Journal of Sex Research, 45(3), 277–286.

- ^ Chu, J. Y., Porche, M. V., & Tolman, D. L. (2005). The adolescent masculinity ideology in relationships scale: Development and validation of a new measure for boys. Men and Masculinities, 8, 93–115.

- ^ a b O’Sullivan, L. F., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2005). The timing of changes in girls’ sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: a prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 211–219.

- ^ Britain: Sex Education Under Fire UNESCO Courier

- ^ Sexualaufklärung in Europa (German)

- ^ http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/repcard3e.pdf

- ^ Adolescents In Changing Times: Issues And Perspectives For Adolescent Reproductive Health In The ESCAP Region United Nations Social and Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific

- ^ SIECUS Report of Public Support of Sexuality Education(1999)SIECUS Report Online

- ^ Sex Education in America.(Washington, DC: National Public Radio, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, and Kennedy School of Government, 2004), p. 5.

- ^ Landry DJ, Singh S, Darroch JE (2000). "Sexuality education in fifth and sixth grades in U.S. public schools, 1999". Fam Plann Perspect. 32 (5): 212–9. doi:10.2307/2648174. JSTOR 2648174. PMID 11030258.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Sex Education in the U.S.: Policy and Politics" (PDF). Issue Update. Kaiser Family Foundation. October 2002. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hauser, Debra (2004). "Five Years of Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Education: Assessing the Impact". Advocates for Youth. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ "Mathematica Findings Too Narrow" (Press release). National Abstinence Education Association. 2007-04-13. Archived from the original on 17 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ Report: Abstinence Not Curbing Teen Sex

- ^ Why Know Says They Are Effective In Increasing Teen Abstinence

- ^ Bearman PS, Brückner H (2001). "Promising the future: virginity pledges and first intercourse". American Journal of Sociology. 106 (4): 859–912. doi:10.1086/320295. S2CID 142684938.

- ^ Brückner H, Bearman P (April 2005). "After the promise: the STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges". J Adolesc Health. 36 (4): 271–8. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.005. PMID 15780782.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Finer LB (2007). "Trends in premarital sex in the United States, 1954–2003". Public Health Rep. 122 (1): 73–8. doi:10.1177/003335490712200110. PMC 1802108. PMID 17236611.

- ^ a b c d Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: the missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58(1), 29–53.

- ^ Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Scott, S., Sharpe, S., & Thompson, R. (1992). Risk, power and the possibility of pleasure: Young women and safe sex. Aids Care, 4, 273-283.

- ^ Thompson, SR. & Holland, J. (1994). Younger women and safer (hetero)sex: Context, constraints and strategies, In C. Kitzinger & S. Wilkinson (Eds.), Women and health: Feminist perspectives. London: Falmer

- ^ Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Scott, S., Sharpe, S., & Thompson, R. (1994). Sex, gender and power: young women’s sexuality in the shadow of AIDS. In B. Rauth (Ed.), AIDS: Reading on a global crisis. London: Allyn and Bacon.

- ^ Furstenberg FF, Geitz LM, Teitler JO, Weiss CC (1997). "Does condom availability make a difference? An evaluation of Philadelphia's health resource centers". Fam Plann Perspect. 29 (3): 123–7. doi:10.2307/2953334. JSTOR 2953334. PMID 9179581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guttmacher S, Lieberman L, Ward D, Freudenberg N, Radosh A, Des Jarlais D (September 1997). "Condom availability in New York City public high schools: relationships to condom use and sexual behavior". Am J Public Health. 87 (9): 1427–33. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1427. PMC 1380965. PMID 9314792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schuster MA, Bell RM, Berry SH, Kanouse DE (1998). "Impact of a high school condom availability program on sexual attitudes and behaviors". Fam Plann Perspect. 30 (2): 67–72, 88. doi:10.2307/2991662. JSTOR 2991662. PMID 9561871.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Lohrmann D, Windsor R (June 2003). "Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: relationships with condom use and sexual behavior". Am J Public Health. 93 (6): 955–62. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.6.955. PMC 1447877. PMID 12773362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)