User:Imzadi1979/MassPike

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by MassDOT | ||||

| Length | 138.1 mi[1] (222.3 km) | |||

| Existed | 1958 (final construction in 2003)–present | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| West end | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Massachusetts | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

The Massachusetts Turnpike (commonly shortened to the Mass Pike or The Pike) is the easternmost 138-mile (222 km) stretch of Interstate 90. The Turnpike begins at the eastern border of Massachusetts in Boston and connects with the Berkshire Connector portion of the New York State Thruway. The Turnpike traverses the state and serving the major cities of Worcester and Springfield. The highest point on the Turnpike is in the Town of Becket in the Berkshire Hills, at elevation 1,724 feet (525 m) above sea level; this is also the highest point on Interstate 90 east of South Dakota.[2]

Route description[edit]

The Massachusetts Turnpike is the major east-west highway in Massachusetts, connecting three of its major cities: Springfield, Worcester, and Boston. It is also the easternmost portion of Interstate 90. The roadway begins at the New York border and continues in a south-easterly direction until the junction with Interstate 84 in Sturbridge; from that point it continues in a north-easterly direction into Boston. The roadway terminates in East Boston at Route 1A, just outside Logan International Airport.

Between the New York border and the I-84 junction, the roadway is a four-lane divided highway, two lanes in either direction. Between I-84 and exit 17 in Newton, it is a six-lane divided highway which grows to eight lanes between the Newton and Cambridge exits where it drops back to six lanes. It stays as a six lane roadway until the Ted Williams Tunnel where it drops back to four lanes until the exit of the tunnel in East Boston.

History[edit]

As Boston’s place as a center of commerce and manufacturing began to grow in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the need to move goods to the city’s ports from growing mills and factories in communities such as Worcester, Lowell and Providence, Rhode Island to warehouses in the city required investments in new methods of transportation. The growth of shipbuilding in the city also required the importation of raw materials from the interior regions. Additionally the newly expanded marketplaces within the city, such as Faneuil Hall, needed ways to bring their products to market. In response to these needs, the city and Commonwealth began a process of expanding transportation access to the city. New infrastructure such as bridges, wharves and ferries were established, often by early public-private corporations chartered by the Commonwealth.[5][6]

The rudimentary system of roads that existed in the region at the time was woefully insufficient for the needs of the merchants, being in need of major overhauls and upgrades that were beyond the financial means of the Commonwealth and municipal governments of the time. The poor quality of the early roadways in the state, as well as others in the young nation, would often make the transportation of goods inland from the ports would often make it economically impractical to transport them via road.[7]

While the military necessity of transporting men and supplies during the revolution helped improve some of the early highways in the states, many of these were not maintained or upgraded after the war’s end. Many roadways lacked bridges and adequate facilities to feed and house travelers on trips that would often take anywhere from a few days to a week to complete. Many communities were also hesitant or unable to provide sufficient capital required to establish or maintain amenities for those who passed through their towns.[8]

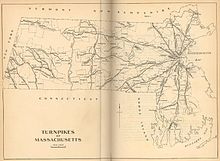

On March 16, 1805, the Massachusetts legislature chartered a system of private roads, or turnpikes, in designed to help facilitate travel and commerce into general laws of the Commonwealth. These turnpikes, named after the system of tollgates used to collect fares from travelers, were based upon a franchises-like system of private operators who would build, maintain and operate the roads using the toll revenue. Unfortunately, the turnpikes often operated at a loss and many folded shortly after their opening.[9]

One such turnpike was designed to run from Roxbury to Worcester and was chartered as the Worcester Turnpike Corporation on March 7, 1806. The Worcester Turnpike was designed to be the primary roadways on the western approach to Boston and utilized a part of the old Connecticut Path along Tremont and Huntington streets, into Brookline and continued west to Worcester along roughly the same route as the modern Route 9. However, the costs of maintaining the road began to spiral as needed bridges in Shrewsbury began deteriorate and mandated requirements in its charter to run and maintain older and unaffiliated roadways along the route made it difficult for the Corporation to maintain profitability. Like many of its contemporary turnpikes, the Worcester Turnpike eventually succumbed to failure in 1841, had its charter dissolved by the Commonwealth, and the roadway was portioned and control transferred to local municipalities.[10]

alt=Figure 2: Map of the various railways entering the city in 1853, The Boston and Albany Railroad is unnamed in this image, but is the line coming in from the lower left corner parallel to the bottom of the image.

One of the primary contributors to the demise of the Worcester Turnpike was the ascendancy of the railroad during the 1830s.[11] Chartered in 1831 by the General Court, the Boston and Worcester Railroad began construction of its line in 1832, and the mainline was completed in July, 1835.[12] The newly completed railroad initially utilized the right of way along another failed turnpike, the Central Turnpike, which ran from Boston to Worcester though Brookline, Wellesley, Natick, Framingham and other communities along what is now the Framingham/Worcester MBTA commuter rail line.[13] As illustrated in fig. 1, the railway originally ran through the tidal flats of the Back Bay and its impact on the city was only felt along the southern sections of the city. While originally designed as a long haul railway, the proprietors of the B&W, and other railways, eventually found that there was a willing market for commuter services along the routes and by 1845 had established a series of commuter rail facilities along its route.[14] Through a series of mergers during the next several decades, the Boston and Worcester Railroad eventually evolved into the Boston and Albany Railroad in 1870, Connecting the capitols of Massachusetts and New York state.[15]

alt=Figure 3: Map of railways in the Boston in the 1880s. The Boston and Albany Railroad comes in at a diagonal from the upper left of the image. The Back Bay can be seen to its right, the South End to its left.

As the city slowly began filling in the Back Bay tidal estuary to establish the South End and Back Bay sections of the city, the rail line went from being a lone causeway in the middle of said tidal estuary to a major transportation cut through the heart of the western sections of the city.(See Fig. 2) Besides being a physical separator, the railroad was also a societal and economic barrier as well; while the South End reclamation project was a municipal project that lacked any form of solid planning, the Back Bay reclamation project was a state-run program that established specific ideas of who would reside within the district. The proximity of the railway also led to an unforeseen effect, suburban flight. With the new rail lines in close proximity to the entire city, many wealthier citizens began migrating to the cities and towns west of Boston. This migration put financial burdens for municipal services such as water and sewer, fire and police on these communities, and help led to drives for them to be annexed by Boston, further expanding the city limits.[16] Despite these issues, by the end of the nineteenth century the western railroad and its contemporaries were helping drive the city’s economy by assisting local industries to bring products to Boston’s port, helping it become the second busiest port on the eastern seaboard.[17]

alt=Figure 4: Huntington St. Rail yards, circa 1930.

To help accommodate the growth in rail traffic, the Boston and Albany constructed two large rail yards, one in the Allston section of city and another adjacent to the Lennox Hotel on Huntington St, adjacent to the Back Bay.(See Fig. 3) While the Boston and Albany and its contemporaries railroad was constructing new yards, other factors that would foreshadow the decline of the city’s fortunes were manifesting themselves through the late nineteenth century and into the early; traffic to the Port of Boston declined, necessitating the Federal government to dredge the main shipping channels and construct new piers to handle larger vessels; AT&T moved its operations and headquarters from Boston to New York in 1910. The problematic relationship between the city and the business sector under the successive mayoral administrations of James Michael Curley drove a wedge between these businesses and the municipal government, souring employers on Boston. Adding to these problems, a series of economic recessionary periods culminating with the Great Depression coupled with heavy tax burden placed the city’s finances into a tailspin. Despite minor uplifts from the mobilization of the two World Wars, by the end of the World War II the city was in dire straits.[18] Much of the state’s infrastructure west of Boston was in a serious state of decay, with the major east-west routes 2 and 9 in need of significant upgrades. At the same time, rail traffic in the region was becoming financially untenable to utilize for material transportation for newly emerging technology companies of the era due to the rail roads’ outmoded pricing structures and limited geographical reach.[19]

1950s and 1960s: the New Boston[edit]

In the period following World War II, Boston had fallen into a deep period of stagnant growth. Its former maritime industries had closed as traffic in the harbor declined; the textile mills that had provided a large portion of the city’s wealth had migrated out of the region seeking new locations that would allow them to maximize revenues; and property development had ground to halt with virtually no new construction of any impact occurring since the beginning of the Great Depression.[20] Boston retail stalwarts such as Filenes and Jordan Marsh had decided to focus their energies and growth into the suburbs; Boston’s citizens had begun had begun to flee to the same suburban pastures as property taxes in the city skyrocketed. As U.S. News and World Report, Boston was “dying on the vine”.[21]

After the end of the war, Massachusetts entered into a period of new highway projects planning that sought to help end the economic malaise the state was suffering from. It was in 1947 that Republican Governor Robert Bradford realized that the Commonwealth needed to implement a standard framework to properly guide the planning and construction of these new roadways. He commissioned a study to produce a new Highway Master Plan for the eastern region, and by 1948 it had been completed. Seeking the political benefits that a major public works project would bring, Bradford put sent his plan to the Democratically controlled Massachusetts legislature for approval, however the Democrats sat on the project until their candidate, newly elected Democratic Governor Paul A. Dever, took office in January 1949.[22]

It was instead Dever who initiated the program to implement the Highway Master Plan for the city shortly after taking office in 1949. Enjoying a Democratic majority within the State House coupled with a Democratic governor for the first time in Commonwealth’s history, he pushed through a series of highway bills with associated gas tax increases totaling over US$400 million (US$3.97 billion in 2014, adjusted for inflation) between 1949 and 1952.[23] To oversee this massive undertaking, Dever brought in former Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Works, William F. Callahan, to once again head the agency he had helmed from 1934 to 1939. Known for his strong personality and drive to get projects completed,[23] Callahan immediately set out to construct three of the proposed highways—the outer circumferential highway aka route 128, the Southeast Expressway, and the Central Artery through the heart of the Boston’s downtown. These three projects, totaling more than US$92 million (US$913 million in 2014, adjusted for inflation) were seen as being essential to the growth of the city in the future. However, the construction these roads took such a large portion of funds that the Commonwealth was unable to provide funds for the Western Expressway project. However, before Callahan could oversee the completion of southern leg of route 128 he was appointed by Dever to run the newly formed Massachusetts Turnpike Authority.[24][25]

Because of the financial strain created by the bond issues used to construct these other highways, the Commonwealth was unable to afford the costs of floating more bonds to fund the expenditures required to construct the Western Expressway along the Western Approach corridor of Boston. Callahan suggested creating a strong, independent, and semi-public transportation authority that could fund the new expressway by floating its own bond issues and financing them through tolls along the highway while having its own powers of imminent domain to secure the land needed to build it. Utilizing the political goodwill he accrued during his tenure as public works commissioner, primarily through extensive patronage hires,[23] Callahan was able to push his idea for the new authority through the Statehouse with ease.[26] The authority was formed in early 1952, and by 1955 it had issued the required bonds needed to construct a 123 mi (198 km) highway from the New York-Massachusetts border to the recently completed route 128 in Weston. Despite the being completed in 1957, many within the Commonwealth quickly realized that the local routes used to get into Boston were still insufficient for the automotive traffic burdens placed upon them.[27]

While the highway construction boom proved to be fortunate for the suburban communities these new roadways passed through, the economy of Boston was still in a fragile state.[28] Realizing that the Boston still needed to be connected to the Turnpike to help reverse its flagging economy and reputation as a municipal has-been, Callahan was tasked in 1955 by the Legislature to create an extension into the city designed to facilitate a turnaround of the city’s fortunes. This new highway would connect the Massachusetts Turnpike to the heart of the city with a 12.3 mile extension of the Interstate. It was his plan to bring the tolled Turnpike from its terminus at route 128 in West Newton into the city along the path of the Boston and Albany Railroad and connect it to the Southeast Expressway. This plan was in line with the 1948 Master Highway Plan for the city, which had always called for a Western Expressway to be built into the city. However, with the passage of the Interstate Highway Act in 1956, the Federal Government provided sufficient funds to the states to construct new highways with a ninety percent subsidy—rendering the need for a toll road into the city obsolete.[29]

Compounding the matter, Callahan’s planned Extension route was not universally accepted by others within the state, such as newly elected Governor John A. Volpe and Newton Mayor Donald Gibbs, who sought to construct a freeway that would follow a different route between the Borders of Newton, Waltham and Watertown along the Charles River and U.S. Route 20 and be constructed using the funds now being provided by the Federal Highway Administration.[30] Additionally, residents of the city of Newton, who would see significant demolition of neighborhoods within the city along with large portions of its central business district to make way for the Turnpike Extension, were also adamantly against the proposed Boston and Albany routing of the road.[31] Newton, through the terms of two mayors, set about fighting the Turnpike proposal through a series of increasingly futile legislative maneuvers in the General Court. Realizing that the needs and wants of the smaller city could not overcome the influence of Callahan within the state capitol, the smaller city would instead redirect its efforts to blocking the highway at the Federal level through the Interstate Commerce Commission and Federal courts.[32] Effected property owners within Boston who were also looking at the possibility of losing their homes and business followed Newton’s lead by filing a series of State- and Federal-level lawsuits that hoped would derail the proposed extension.[33]

The Prudential Company[edit]

Adding to Callahan’s numerous problems with those in opposition to the new roadway, the Prudential Life Insurance Company announced that it was in the process of acquiring the 32-acre Boston and Albany Tremont St. rail yard for the purpose of constructing a brand new building and associated complex to house its Northeastern American operations at about the same time as the Commonwealth’s plan to bypass the Turnpike Authority was being announced. This proposed development stood square in the middle of the Boston leg of Callahan’s planned Turnpike extension, and could possibly kill his proposed extension.[34][35] While many opponents within and out of the city looked upon the Prudential announcement as the possible final-nail-in-the-coffin for Callahan’s proposed toll road, Boston Redevelopment Authority head Edward J. Logue saw Callahan’s Prudential problem as a way to overcome issues the BRA was having in obtaining approval for the Prudential project from the city.[34][36]

Logue was in many ways the equal to Callahan; a driven man who sought the power to get things done as the head of a semi-independent authority whose structure had been modeled on Callahan’s Turnpike Authority.[34][37] Logue, who was responsible for many Urban renewal projects in Boston at the time, including the construction of Storrow Drive and the West End redevelopment project, realized the Prudential project was essential to Boston’s redevelopment efforts. The main issue holding up the project was a lack of consensus over tax-breaks Prudential was demanding in order to move forward with the project.[38] Additionally, several legal decisions were handed down by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court questioning the constitutionality of the land takings required to build the complex.[34][39]

Adding to the problems associated with the Prudential project, during 1960 and 1961 there was a series of allegations were made against Callahan claiming he had been engaging in illegal activities related to his second tenure as Public Works Commissioner. These allegations included charges of financial kickbacks, bid rigging, and other questionable practices. This led to a corruption trial which threw a pall on his reputation that did not help with his drive to construct the Turnpike extension. On top of the legal allegations, a group of three professors from MIT and Harvard made public allegations the Turnpike Authority had been using inflated numbers to push through its bond issues, thus artificially inflating their values. This led to failed series of bond issues that critics hoped would prevent the Turnpike Authority from raising the needed funds for construction.[40]

It was in the midst of these many legal problems, that in April 1960 Prudential announced that continuation of their building project was contingent on direct highway access via a toll road along the Boston & Albany Rail Road right of way.[34][40] Additionally, Prudential would lease air rights to the parcels from the Turnpike Authority and purchase a large portion of bonds issued by the Authority. Despite this agreement, Governor Volpe was still trying to nix the Turnpike’s plans along the Boston and Albany right of way, filing the city of Newton’s request with the ICC to stop the construction of the roadway. It was only after a series of meetings between Volpe, Callahan and Prudential executives that finally persuaded the Governor to withdraw the ICC filing and reluctantly support the toll road.[41] With the new deal in place, a not-guilty finding in the criminal case, and public relations push back to the allegations of market tampering by the Turnpike Authority, the bond measures were once again seen as a sound investment and investors quickly picked up the $175 million (US$1.4 billion in 2014, adjusted for inflation) bond issuance.[40][42] With the Turnpike-Prudential agreement in place, Logue was able to petition the General Court to once again authorize a land taking deal and tax-deferment bill, which was passed rather quickly and signed by then Governor Foster Focolo. While this new bill was again deemed unconstitutional by the SJC, in its decision the Court provided a framework for the legislature to construct a bill that would pass constitutional muster. The bill also gave Logue’s BRA considerable powers over the redevelopment project, allowing him to rapidly move forward with permit approvals and tax issues.[34][40] The Turnpike-Prudential deal linked with the Logue and the BRA’s new powers to move the project forward quickly quieted much of the remaining opposition to the new roadway, and cemented the idea of air right development as an integral part of the Turnpike moving forward.[43] By 1965 the Massachusetts Turnpike had been connected to the Central artery, and the Prudential Center was on its way to completion; however Callahan did not live to see this. On April 24, 1964, Callahan died of a massive heart attack at his home.[44]

1970s: Gridlock[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2014) |

1980s and 1990s: A new highway[edit]

When designing the Central Artery/Tunnel project in the 1970s and 1980s, the horror stories regarding urban renewal projects such as the construction of the old viaduct in the 1950s weighed heavy on the minds of Frederick Salvucci and his team. It was realized early on that the Commonwealth could not just lay waste to parts of the city and pave them over; the state would have to ensure that construction would balance the needs of the highways against the livability of the city and neighborhoods the project would pass through. Mitigation efforts would be of utmost importance in moving ahead with the project.[45][46]

The notions of using existing rights of way or areas where neighborhood displacement would be minimized were applied to the second extension of the Turnpike as part of the CA/T project. Salvucci deliberately planned to bring the East Boston Extension through areas with little or no occupancy or those properties already owned by the Commonwealth. As a result, East Boston saw almost no takings of buildings or homes through eminent domain or the destruction of neighborhoods because construction was relegated to the unoccupied areas of the South Boston Seaport and Logan. Like the first Turnpike extension, the connection of the Turnpike to East Boston was also designed to provide an economic stimulus to the city, this one to revitalize the desolate Seaport district.[47]

2000s: Aftermath[edit]

A pair of planned mass transit projects will also continue using the railway right of way to help build out the Turnpike. The Beacon Park Rail Yard and ShurFlo Chemical transfer station in Allston, derelict for several years since CSX moved operations out of the city in 2013, are set to be used by the Turnpike to straighten the “kinked” section of the roadway through the area. (Dyer 2) This will allow for newer forms of tolling, expanded rapid transit, reduced pollution and a replacement of a series of ramps and viaducts that cut the area off from the rest of the city. A new local roadway alignment replacing the old ramps and viaducts in place for the past half century will allow commercial development and expansion of Harvard and Boston University campuses into areas now laid fallow or unusable because of the cut.[48][49][50]

Future[edit]

Future plans in the state call for the re-routing of the highway over the former Beacon Park Yard, in order to free up space and make the highway safer. Plans call for the beginning of construction in 2016, with completion scheduled for 2020.[51]

Exit list[edit]

The Massachusetts Turnpike uses a system of sequential exit numbered interchanges. More have been added since the Turnpike first opened, leading to situations like Exit 11, which is a minor state route, and 11A, which is a major Interstate Highway 10 miles (16 km) away. In the Boston area, some of the interchanges are solely onramps and are not signed as exits.[52]

This section is missing mileposts for junctions. |

| County | Location[53] | mi[53] | km | Exit[54] | Destinations[54] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berkshire | West Stockbridge | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | Continuation into New York | |

| 2.736 | 4.403 | 1 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||

| 2.9 | 4.7 | West Stockbridge Toll Plaza (western end of ticket system) | ||||

| Lee | 8.5 | 13.7 | Lee Service Plaza | |||

| 10.592 | 17.046 | 2 | ||||

| Hampden | Blandford | 29.0 | 46.7 | Blandford Service Plaza | ||

| Westfield | 40.434 | 65.072 | 3 | |||

| West Springfield | 45.740 | 73.611 | 4 | |||

| 46.293 | 74.501 | Connecticut River | ||||

| Chicopee | 49.041 | 78.924 | 5 | |||

| 51.154 | 82.324 | 6 | ||||

| Ludlow | 54.780 | 88.160 | 7 | |||

| 55.6 | 89.5 | Ludlow Service Plaza | ||||

| Palmer | 62.641 | 100.811 | 8 | |||

| Worcester | Sturbridge | 78.300 | 126.012 | 9 | Former I-86 east; eastern terminus of I-84 | |

| Charlton | 80.2 | 129.1 | Charlton Service Plaza | |||

| 86.2 | 138.7 | Weigh Station (eastbound) | ||||

| Auburn | 90.049 | 144.920 | 10 | I-290 east to Worcester; I-395 south to Oxford and Webster; Route 12 north to Auburn; Route 12 south to Charlton and Sturbridge[56] | ||

| Millbury | 93.642 | 150.702 | 10A | US 20 to Auburn and Westborough[57] | ||

| 96.343 | 155.049 | 11 | ||||

| Westborough | 104.6 | 168.3 | Westborough Service Plaza (westbound) | |||

| Middlesex | Hopkinton | 106.236 | 170.970 | 11A | ||

| Framingham | 111.181 | 178.928 | 12 | |||

| 114.4 | 184.1 | Framingham Service Plaza (westbound) | ||||

| 116.600 | 187.650 | 13 | ||||

| Natick | 117.6 | 189.3 | Natick Service Plaza / Fast Lane Service Center (eastbound) | |||

| Weston | 122.600 | 197.306 | 14 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 123.456 | 198.683 | Weston Toll Plaza (eastern end of ticket system) | ||||

| 123.458 | 198.686 | 15 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||

| Newton | 125.207 | 201.501 | 16 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| 127.553 | 205.277 | 17 | Washington Street / Galen Street / Centre Street – Newton, Watertown | |||

| Suffolk | Boston | 130.991 | 210.810 | 18 | Cambridge Street / Storrow Drive – Brighton, Cambridge | Eastbound left exit and westbound entrance |

| 19 | Allston Toll Barrier | $1.25 Cash; $1.00 Fast Lane | ||||

| 20 | Cambridge Street / Storrow Drive – Brighton, Cambridge | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||||

| 132.863 | 213.822 | 21 | Westbound entrance only | |||

| West end of Prudential Tunnel | ||||||

| 133.344 | 214.596 | 22 | Dartmouth Street – Prudential Center, Copley Square | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 133.586 | 214.986 | 22A | Clarendon Street | Westbound entrance only | ||

| East end of Prudential Tunnel | ||||||

| 133.876 | 215.453 | 23 | Arlington Street | Westbound entrance only | ||

| 134.315 | 216.159 | 24 | Split into left exits 24A (South Station), 24B (north), and 24C (south); no eastbound entrance from I-93 north | |||

| 134.773 | 216.896 | 25 | South Boston | Via Summer Street | ||

| Ted Williams Tunnel under Boston Harbor | ||||||

| East Boston Toll Barrier (westbound only) $3.50 Cars, $5.25 Commercial Vehicles (2+ axles), $1.75 per additional axle, $12.25 maximum | ||||||

| 137.239 | 220.865 | 26 | ||||

| 138.15 | 222.33 | – | Eastern terminus of I-90 | |||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | ||||||

Service plazas[edit]

There are 11 service areas (plazas) on the Massachusetts Turnpike, named for the towns in which they are located. Each plaza offers Gulf gas stations and Gulf Express convenience stores. Most offer McDonald's restaurants, with some plazas having Boston Market and D'Angelo as the main food offerings. Some plazas also have secondary food such as Auntie Anne's pretzels, Ben & Jerry's ice cream, Papa Gino's pizza, Original Pizza, and Fresh City restaurants. Some restaurants at some plazas also offer a drive thru.

The plazas are:[58]

- Lee Plaza between exits 1 and 2

- Blandford Plaza between exits 2 and 3

- Ludlow Plaza between exits 7 and 8

- Charlton Plaza between exits 9 and 10

- Westborough Plaza between exits 11A and 11 (westbound only)

- Framingham Plaza between exits 13 and 12 (westbound only)

- Natick Plaza between exits 13 and 14 (eastbound only)

All service areas except for the westbound Lee Plaza and the eastbound Blandford Plaza feature dog walk areas. All service areas except the westbound Lee, the Blanford, and the Ludlow Plazas offer special family restrooms. A weigh station is located on the eastbound side of the turnpike in Charlton between exits 9 and 10.

Notes[edit]

- ^ It has been reported variously that the sign was changed due to confusion among motorists who sometimes mistakenly turned in the direction the arrow pointed (right) when attempting to enter the turnpike,[3] or that it was the result of a letter campaign describing the signs as offensive to Native Americans.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ "State Numbered Routes with Milepoints in District 4" (PDF). Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ Vanhoenacker, Mark (August 18, 2014). "What Does This Beloved Road Sign on the Massachusetts Turnpike Actually Mean?". Slate.com. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Montgomery, M. R. (February 28, 1991). "Redrawing the Native American Image". The Boston Globe. p. 69. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

Too many tourists, non-English readers and reflexive drivers were always turning right, following the politically incorrect arrow to nowhere

- ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1917&dat=19891122&id=2XIhAAAAIBAJ&sjid=hYgFAAAAIBAJ&pg=1152,5928057.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[full citation needed] - ^ Wood, Frederick J.; Karr, Rondald D. (1997) [1919]. The Turnpikes of New England (Revised ed.). Branch Line Press. p. 3. ISBN 0942147057.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Kennedy, Lawrence (May 1 1994). Planning the City Upon a Hill: Boston Since 1630 (3rd ed.). Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 46–50. ISBN 0870239236.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wood, Karr p. 3

- ^ Wood, Karr p. 5-6

- ^ Wood, Karr p. 8-10

- ^ Wood, Karr p. 138-147

- ^ Wood, Karr p. 146-147

- ^ Harvard University Library. Boston and Albany Collection

- ^ "Boston and Albany Railroad Station". Historic Framingham. January 5, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ Kennedy p. 46

- ^ Harvard University Library

- ^ Kennedy p. 68-71

- ^ Kennedy p. 110-11

- ^ Kennedy p. 130-154

- ^ Tsipis, Yanni (February 18, 2002). Building the Mass Pike. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0738509728.

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 9-10

- ^ Berkman p. 200

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Central Artery p. 7-8

- ^ a b c "Baystate Notes Spending Record". The New York Times. November 5, 1958.

- ^ Tsipis, Route 128 p. 8-9

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 27-28

- ^ Berkman p. 180-181

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 27-29

- ^ Kennedy p. 168

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 47-48

- ^ Britten

- ^ Berkman p. 170-173

- ^ Berkman p. 177-181

- ^ Fenton

- ^ a b c d e f Aloisi, James (October 3, 2013). "Collins and Logue: a formidable team". CommonWealth Magazine. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 47-48

- ^ Kennedy p. 172-173

- ^ Aloisi, James (October 26, 2013). "The New Boston was a mix of good and bad". CommonWealth Magazine. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Kennedy p. 172

- ^ Berkman p. 188

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Anthony (June 20, 1961). "Massachusetts Turnpike Chief Criticized in Rising Scandals". The New York Times.

- ^ Tsipis, Building the Mass Pike p. 48

- ^ Berkman p. 188

- ^ Berkman p. 188-189

- ^ Funeral

- ^ DOT

- ^ Altshuler pp. 95-96

- ^ Altshuler pp. 95-96

- ^ Ross p. 2

- ^ Dyer p. 1

- ^ McMorrow p. 2

- ^ Rocheleau, Matt (October 23, 2013). "Photos: Conceptual designs of project to straighten Mass. Pike in Allston". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ MassDOT Highway Division. "I-90 Interchange Numbers". Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ a b MassDOT Planning Division. "Massachusetts Route Log Application". Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Massachusetts Department of Transportation. "Exit Numbers and Names: Route I-90 (West Stockbridge to Boston)". Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Google (August 22, 2014). "Street View" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Google (August 22, 2014). "Street View" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Google (August 22, 2014). "Street View" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ "Travel Service Plazas & Tourist Information Centers"

- Ingraham, Joseph C. "Boston To Chicago; New Section of Thruway Completes Express Route Between Cities Boston To Chicago". The New York Times. May 24, 1959. Resorts Travel section, page XX1.

External links[edit]

- Official Web Site

- The Roads of Metro Boston - Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90)

- Big Dig Ceiling Collapse -- The Boston Globe

- Big Dig Problems -- The Boston Globe

- Finishing the Big Dig -- The Boston Globe

- Amorello, options were left exhausted -- The Boston Globe

- A vacancy at the helm -- The Boston Globe

- Top staff is leaving Mass. Pike -- The Boston Globe

- I-90 connector reopens to traffic -- The Boston Globe

- Designer proposed more bolts in Big Dig -- The Boston Globe

- Tunnel bolts never inspected -- The Boston Globe

- Pike board acts to end tolls west of Route 128 -- The Boston Globe

- Ending Pike tolls is called illegal -- The Boston Globe

- Late Design Change Is Cited in Collapse of Tunnel Ceiling in Boston -- The New York Times

- AG, alleging negligence, will sue in tunnel cave-in -- The Boston Globe

- Reilly says neglect with tunnel was criminal -- The Boston Globe

- Commonwealth of Mass. v. Bechtel Corporation, et al.

- Cheaper, faster path led to failure -- The Boston Globe

- I-90 connector west opens -- The Boston Globe