User:Ifly6/Peloponnesian War

![]() Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

This page is a soft redirect.

The Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BC) was a conflict in Ancient Greece fought between the Athenian-led Delian League and the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League.[1] The fighting took place largely in the eastern Mediterranean, with battles ranging as far west as Sicily and as far northeast as the Hellespont.

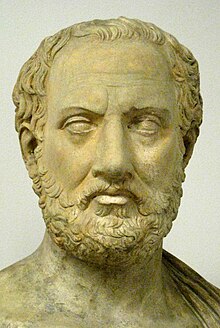

According to the Greek historian Thucydides, the main primary source on the war, the underlying cause of the conflict was Sparta's unwillingness to accept rising Athenian power which would have challenged Spartan pre-eminence.

...

There were two main phrases of the war, split by the Peace of Nicias. The first phase, from 431 to 421 BC, is known as the Archidamnian war. The second phase is known as the Ionian or Decelean War, which was fought starting from the ill-fated Athenian expedition to Sicily in 415 until Athen's surrender in 404 BC.[1]

Background[edit]

Peloponnesian League[edit]

The Oxford Classical Dictionary reports a start date for the League some time in the sixth century BC, taking the form of a loose set of alliances between Peloponnesian cities and the Spartans which transformed into a permanent formal alliance c. 500 BC. Sparta, unlike the members of the League, had a veto over offensive action and always held overall command but was required to come to the aid of League members. This structure served to ensure Sparta had sufficient manpower to ensure its control over its large helot population and also gave oligarchic city-states security against democratic revolution.[2]

Evidence for the early Peloponnesian League is very scarce. There are two major views on its organisation. The first, widely held in the early 20th century, was that it was an organisation dominated by Sparta with broad military guarantees for each member and a league congress binding all members.[3] The second, more recent, viewed the league in terms of a loose organisation with infrequent league congresses meeting only to decide offensive action and largely serving as a defensive alliance.[4]

Delian League[edit]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Plataea, the Spartans had led the anti-Persian coalition as it went northeast to punish Greek states who had sided with the Persians and remove cities from Persian influence.[5] When Sparta's commander was withdrawn, Athens assumed control of the coalition, which Sparta accepted.[6] The Delian League was formed to facilitate this campaign in the winter of 478–77 or 477–76 BC.[7] Some 150 city-states joined the League and continued the war on Persia through to the victory of the river Eurymedon around 467 BC.[8]

Contributions were levied in ships or money; most larger states chose to contribute in ships with many smaller states contributing money.[9] However, over time, Athens, supported by allied money, became relatively more able to compel monetary contributions by force.[10] The city aggrandised itself in League operations by settling cleruchies – special colonies under direct Athenian control which served also as local Athenian garrisons – on territory won by League operations.[11] By force, it also put down attempts to leave the League (Naxos c. 470 BC; Thasos c. 464 BC).[12] Athenian refusal to permit the League to disband after the expulsion of the Persians from the Aegean and much of Asia Minor indicated that it intended to convert it into a maritime empire.[13]

Breakdown of Spartan–Athenian relations[edit]

A formal break between Sparta and Athens came only in 464 BC. Athens, at the politician Cimon's urging, sent troops to Sparta to aid in the suppression of a helot revolt in the aftermath of an earthquake. Sparta, fearing that the Athenian soldiers would aid the helots on their own accord or otherwise do so under new orders, expelled the Athenians.[14] After this break, Athenian ambitions against Aegina drew the Delian League into the First Peloponnesian War, which saw Aegina defeated and forced into the Delian tributary system.[15]

At the same time, Athens continued operations against the Persians and sent an expedition to Cyprus.[16] While there, the Cypriot expedition turned into an Egyptian expedition. The fleet in Cyprus responded to a call for aid from Lybian king Inaros II and moved to support an Egyptian anti-Persian revolt.[17] Persian attempts to induce Sparta to invade Attica were unsuccessful but their military response in Egypt was overwhelming: the Egyptians and Greeks were kicked out of occupied Memphis before being surrounded and besieged in Prosopitis.[18] After a long siege, the island was taken – likely in 454 BC – and the Greek expeditionary force destroyed.[19]

Faced with sustained military pressure and fear of Persian reprisals, the League treasury at Delos was moved to Athens in 454 BC; it is likely that the League's assembly then stopped meeting.[20] The Athenians also pushed their allies more strictly for contributions, turning the character of the League from alliance to Athenian empire.[21] Athenian interference in allied states' affairs grew during the 450s with dispatch of Athenian garrisons and overseers,[22][23] likely reflecting the desire of many cities to defect or withdraw from the League.[24]

With the close of the First Peloponnesian War in 445 BC there was some optimism that the two major powers could co-exist peacefully.[25] Under the terms of this Thirty Years' Peace, Athens and Sparta agreed to stay out of the other's alliance networks. To that end, there would be no interference in other other's allies and the hegemons received a free hand to coerce the compliance and loyalty of their members. The two hegemons also permitted neutral city-states to join either alliance and agreed to settle disagreements by arbitration.[26] This settlement, in effect, recognised the Spartans as masters of land and Athenians as masters at sea.[27] In the years after 440 BC, however, amid a series of revolts in the Delian League, the Peloponnesian League considered but narrowly rejected intervention.[28]

Events starting from 435 BC destabilised the international situation. A civil war between democrats and oligarchs in Epidamnus, a Corcyran colony, triggered pro-democratic intervention by Corinth, Corcyra's mother city and a member of the Peloponnesian League. Corcyra, after defeating the Corinthians at sea, called for Athenian aid in early 433 BC against Corinth. Athens, fearing Corcyran absorption by Corinth and the Peloponnesians, allied with Corcyra. After some inconclusive fighting in late summer 433 BC, Corinth and Athens were now in direct opposition.[29] By this time, the Athenian politician Pericles was pushing a hard line against the Peloponnesian League and the Spartans; inscriptions attest to Athenian curtailing of civic building programmes so that underspends could be diverted to dockyards and the Athenian Long Walls.[30]

Athens ordered its tributary Potidaea, a Corinthian colony, to dismiss its mother city's dispatched magistrates during the winter of 433–32 BC. Seeking and receiving support from Sparta and Macedon, Potidaea refused and revolted against Athens with its neighbours. The Corinthians sent forces to reinforce Potidaea but the city was put under siege; the Corinthians then demanded Sparta act to fulfil its obligations to Potidaea.[31] Later in 432 BC, Athens started an embargo on the Peloponnesian League member Megara. Coupled with complaints from Aegina that Athens was infringing the autonomy guaranteed by the Thirty Years' Peace, the Peloponnesian League then met to discuss a response.[32]

Outbreak of war[edit]

There are two discussions of the start of the war. The first comes from Thucydides, positing that the Spartans voted twice, first holding that the Athenians had violated the Thirty Years' Peace and then declaring war with a second vote.[33] Some historians have suggested based on Diodorus there were instead three votes. The first vote is the same; the second vote dispatched an official Peloponnesian League embassy to Athens demanding rescission of the Megarian Decree; when the ultimatum was rejected, partially at the insistence of Pericles, the Peloponnesian League then voted for a third time and declared war.[34]

In the Thucydidean narrative, the first vote, on whether the Athenians had violated the Thirty Years' Peace, involved two separate locations. Thucydides' ordering[35] has the first speech from Corinth before the Peloponnesian League, condemning Athenian aggression, followed by an Athenian speech in defence.[36] A second set of speeches, before a closed session of the Spartan assembly, has the Archidamus II, king of Sparta, arguing against war on the basis of unpreparedness and difficulty, with the ephor Sthenelaidas instead stressing the moral question and dismissing Archidamus' warnings.[37] The credibility of the speeches by the Corinthians, Athenians, and Archidamnus is in doubt: respectively, the Corinthians' speech uncredibly discusses Athenian history rather than Spartan inaction, the Athenians present were there on alleged other business and may be a literary insertion, and Archidamnus' warnings are not entirely compatible with his actions in the early part of the war.[38]

Thucydides then has the Spartans declare that the Athenians had violated the peace treaty and then call a Peloponnesian League conference. Buttressed with a favourable response from the Pythia at Delphi, the Corinthians secure their vote for war.[38] Regardless, after the declaration of war, there were some attempts to avoid hostilities by negotiation.[39] A Spartan embassy reiterated their demands and demanded the exile of Pericles; Athens responded with similar demands. Sparta attempted to negotiate for the rescission of the Megarian Decree. When this was rejected, a last Spartan embassy then asserted that Sparta wanted peace and that there would be peace if Athens disbanded its empire. Pericles induced the Athenians to reject all these demands, arguing that any acquiescence to Spartan demands would lead to further demands and that acquiescence too would sully Athenian honour.[40]

However, according to Thucydides, the main cause of the war was not any of these specific grievances, but rather, Sparta's fear of rising Athenian power.[41] The timing was also good for Sparta: Athens' preoccupation in the siege in Potidaea gave Sparta an opportunity to attack.[42] Envoys stopped being sent but no actual fighting occurred until Sparta-aligned Thebes attacked Athens' ally Plataea (location of the famous Persian War battle) in spring 431 BC. The Spartans then invaded Attica eighty days thereafter.[43]

Archidamian war[edit]

The first decade of the war is called the Archidamnian war, named for Archidamus II of Sparta.[44] Much of the earlier part of the war was largely indecisive, with repeated Spartan invasions of Attica from 431 to 425 BC. They accomplished little in the face of similarly repetitive Athenian withdrawals.[45] After years of inconclusive fighting, largely in peripheral areas, the Athenians secured a major victory when they took hundreds of Spartans as prisoners-of-war in 425 BC. The Peace of Nicias in 421 BC brought an end to the war, which saw Sparta accede to Athenian parity.

Events[edit]

431 BC[edit]

The first action of the war was in 431 BC outside Athenian-allied Plataea. A pro-Theban group there arranged an insurrection which succeeded in capturing the city for a short time until its pro-Athenian inhabitants rose up against the insurrectionists. After defeating the pro-Theban forces, they defeated a Theban army in battle.[46]

Repeating the Spartan strategy from 446 BC which forced Athens to accede to the Thirty Years' Peace, Archidamus II invaded Attica at the head of a large hoplite army seeking a decisive land battle.[45] Pericles' had by this time convinced the Athenians to undertake a largely defensive strategy in Attica. They therefore withdrew all their chattels and populations from the countryside into the area within the Long Walls. Archidamus' expectations that the Athenians would challenge his army in the field were unmet – though some in Athens, such as Cleon, agitated to fight – while Athenian cavalry harassed his lines of communication. After a short campaign, the Peloponnesians continued through northern Attica and into Boeotia.[47]

An Athenian naval squadron, operating during the Archidamian expedition, sailed around the Peloponnese and started raiding in the gulf southwest of Athens between it and the Peloponnese. An Athenian raid against Methone was beaten back while an attack on Elis was successful for a couple of days before the main Elean army forced Athenian withdrawal. Further attacks against Corinthian possessions were, however, successful: one of their ports was taken and one of their allied tyrants was expelled. Athens took the island of Cephalonia, giving it a base of operations from which to blockade the Peloponnesian peninsula. Some of these successes were, however, reversed in the winter during a Corinthian counteroffensive.[48] Further Athenian activities saw the removal of Aegina's population and its substitution with an Athenian colony. Athenian bases were set up there and on Atalante.

The Athenian siege of Potidaea continued through the year. The Thracian Odrysian kingdom was brought onto the Athenian side through dynastic marriage.[49] Late Athenian raids against Megara were led by Pericles personally and at the end of the year, Pericles delivered his famous Funeral Oration commemorating those Athenians who had died during the war so far.[50]

430 BC[edit]

The year 430 BC started with a Peloponnesian expedition into Attica. But before that invasion arrived, Athens was hit by plague.[50] Although Thucydides gave a substantial description of the symptoms to allow later generations to identify it, the literary descriptions were insufficient and many causative agents – bubonic plague, influenza, typhoid fever, smallpox, epidemic typhus, and measles – had been suggested.[51] Archaeological microbiologic evidence from mass burials conducted during the plague has, however, suggested typhoid fever.[52][53][54] Athenian fatalities were severe, ranging between a quarter and a third of the population.[55] The Athenians of the time blamed various things: Peloponnesian sabotage, divine intervention against Athens pursuant to a pro-Peloponnesian Apollonian prophecy,[56] and moral decay.[57]

Athenian naval forces were reinforced and attacked Epidaurus, across the Saronic Gulf from Athens. Pericles' intentions may have been to sufficient places to renew the alliance with Argos or establish Athenian control over the Saronic Gulf entire.[58] Under Pericles, they landed in sufficient numbers that the Epidaurians avoided battle. Unable, however, to take the city, Pericles' forces moved simply to pillage the countryside and continued south towards Troezen, Hermione, and Halieis before sailing the Argolic Gulf to Prasiae in Spartan Laconia. After these successes, Pericles returned north to Athens to pick up reinforcements with which to take Potidaea and end the rebellion there. These plans were, however, ruined by spread of the plague.[59] Regardless, Potidaea fell that year. The defenders and citizens were given terms, to the consternation of the Athenian assembly, and the city was reoccupied by Athenian colonists.[60]

Thucydides reports that plague and the second Peloponnesian invasion led to Athens sending ambassadors to Sparta for terms. No further details, however, are given. Pericles was attacked for his role in starting the war and his leadership to date; he was deposed from office. Peloponnesian naval operations attempted to take some Athenian possessions but were unsuccessful. Their attempts to detach Thrace from Athens failed when Thrace handed over the Peloponnesian ambassadors to the Athenian assembly, who voted their summary execution. Persian forces, exploiting Athenian inattention, took the Delian League member Colophon in Ionia.[58]

429 BC[edit]

Peloponnesian forces had two main goals for 429 BC. The first goal was to take Plataea for Thebes. Sparta attempted to negotiate for Plataean neutrality but these aims were rejected when Athens promised its support. Archidamus then besieged the city by circumvallation. The second goal was to occupy Ambracia. Corinth argued successfully that capture of Ambracia would give them the strategic position necessary to retake some the Ionian Islands to the west of the Peloponnese, breaking the Athenian blockade and isolating the Athenian allies Corcyra and Naupactus.[60] After defeat in an ambush, however, the Peloponnesian expedition was called off. The Peloponnesians then suffered further naval setbacks against superior Athenian seamanship before conducting a successful surprise attack on Athenian Salamis.[61]

428 BC[edit]

Archidamus was still besieging Plataea at the start of 428 BC when he launched another largely unsuccessful invasion of Attica.[62] Although the war was named for him, he died some time in early 427 BC.[63]

Athens had intended to launch a raiding expedition to the Peloponnese coast the previous year but was stopped, almost certainly due to plague. Postponed to 428 BC, the forty ships were diverted to Mytilene (located on the island Lesbos) when news arrived that a revolt against Athens was being planned.[62] That Mytilene and allied cities on Lesbos were the last of the autonomous states – allies providing ships instead of cash tribute – in the Delian league indicates the strength that Athenian subjects desired independence.[64]

When the Athenian ships arrived, the Mytileneans requested time for an embassy to Athens which was a pretext for a request for Spartan aid. Pleading their case before the Peloponnesian League, assembled in this instance at Olympia, they claimed that the plague had fatally weakened Athens. Accepted into alliance, Peloponnesian forces then advanced again into Attica, while relief forces were sent to Lesbos.[62]

Mytilenean forces were sufficient for the year to hold against the Athenian expedition, which was severely lacking in land forces. Athens reinforced their expedition to Lesbos with some thousand hoplites but was also distracted by other smaller tax revolts. Financial pressures in the Athenian empire are demonstrated by the introduction, for the first time, of a property tax.[65]

427 BC[edit]

The Peloponnesian League's reinforcements to Mytilene arrived seven days too late. After running low on food, Mytilene surrendered after its lower classes (armed by the city elite to bolster its military strength) demanded a fairer distribution of food or the surrender of the city. After learning of the surrender, the Peloponnesian reinforcements withdrew before they could be stopped by Athenian forces in the area.[66]

After their surrender, what followed in Athens was the Mytilenean Debate, where the Athenian Assembly deliberated the final disposition of the the Mytileneans. Cleon, characterised in Thucydides as a violent demagogue, argued that the Athenians needed to deter others by example from revolting; his opponent in Thucydides, one Diodotus, argued instead that deterrence was of little value in this instance because revolters expected their revolts to succeed and that executing those who had surrendered would counterproductively deter surrender.[67]

The Athenian assembly first resolved to execute all the men and enslave all women and children to punish their revolt. The next morning, however, the assembly realised its revulsion from the previous day's decisions and repealed the decree entire.[68] A second ship, promised a large reward from Mytilene's envoys in Athens if they were to make it there in time,[69] exhausted itself to make the best time to Lesbos and arrived mere moments before the Athenian general there started reading out his orders. The city was spared, though its elites who had led the revolt were executed; the city's fleets and walls, as normal, were destroyed.[70]

Plataea finally surrendered early in the year. At Theban insistence, the defenders were all executed and the women sold into slavery; the city was then destroyed.[71] Thucydides then reports the course of a civil war in Corcyra. The oligarchs attempted to seize the city and remove it from the Athenian alliance. They were stopped after forces arrived from Naupactus (a Delian League member) to intervene. However, they were defeated by an arriving Spartan naval force, which withdrew when superior Athenian forces were sighted. The democrats in the city then launched an attempt to purge the city of their enemies which, after a week of chaos, left only some 500 citizens alive.[72]

An Athenian naval expedition to Rhegium, located in modern Calabria on the southwestern tip of Italy, attacked the Aeolian islands north of Sicily.[73] Plague again struck the Athenians joined this time by earthquake; the Spartan invasion for that year, led by Archidamus' son Agis II, was called off due the bad portents.[74] Spartan fear of divine punishment, along with entreaties from the Delphic oracle, led to the exiled king Pleistoanax being recalled some time between the summers of 427 and 426 BC.[75]

426 BC[edit]

Athens started two maritime invasions, against Leucas and Melos, but both were unsuccessful. The operation against Leucas was diverted by the contingent from Naupactus into Aetolia. Beset by Aetolian skirmishers, however, the Athenian hoplites suffered heavy losses and were forced to retreat to Naupactus, losing one of their generals.[76] Athens also began a land incursion into Boeotia, the first of the war, likely as a response to the Peloponnesian capture of Plataea. The invasion of Boeotia was successful, defeating Thebes and Tanagra, allowing the Athenians under Nicias to pillage coastal Locris.[77]

The Aetolians, with Spartan and Corinthian support, moved to counterattack the Athenians holed up at Naupactus but Athens was able to secure Acarnanian support and reinforce the city, causing the Peloponnesian-aligned coalition forces to divert to divert against Acarnania and Amphilochia.[78] Responding to the call for assistance, the Athenians at Naupactus moved to reinforce the Acarnanians under Demosthenes and defeated the Peloponnesian force at the Battle of Olpae. The Spartan contingent, almost surrounded, sought and secured separate terms for an un-harassed withdrawal and then fled the scene of the battle. Ambracian reinforcements, ambushed unawares, were destroyed, forcing the city to make a separate peace with the Acarnanians under gentle terms.[79] Athenian successes in the campaign were minor given the costs involved, but the clear victories themselves, the first in the previous three years of war, justified a series of monuments dedicated by the Athenian and Messenian victors.[80]

The plague in Athens continued. Attempts to stem the still-continuing plague by removing from the island of Delos all buried corpses were unsuccessful, as was the revival of a Delosian festival in the spring.[81]

425 BC[edit]

Athenian operations in the western Mediterranean near Sicily continued from the previous year, though it is not clear what goal they were seeking. The build-up of forces, however, led to a Syracusan response which caused fighting near Messina and a naval attack on Rhegium.[82]

In response to an Athenian naval invasion of Pylos seeking to establish a fort there, a Spartan force containing a substantial number of aristocrats was poorly deployed onto the island Sphacteria where they were then cut off by Athenian naval forces.[83] The Spartans placed such a high value on the lives of these citizens that an embassy was sent to Athens offering a status quo peace, likely without consulting their Peloponnesian League allies. The embassy, however, was rejected by Athenian hardliners led by Cleon who demanded harsher terms.[84] After the blockade drew on for some months, Cleon criticised Nicias and the upper-class Athenian generals for failing to take the island. Challenged to do it himself, Cleon was acclaimed by the Athenian assembly to a special command against the island garrison.[85] Achieving tactical surprise, Cleon and Demosthenes' forces cornered the Spartan garrison on a hill and, seeking hostages, offered terms.[86] Surprisingly for Greek contemporaries, the Spartans accepted, surrendered their fleet, and proceeded into Athenian captivity.[87][88]

Taking some 120 hostages, their presence then precluded – on the threat that they would kill the hostages – any future Peloponnesian armed expeditions into Attica.[89] A series of Spartan attempts to negotiate for their return were rebuffed amid extreme demands.[90][91] Athens continued on the offensive and, under Nicias, landed forces near Corinth. Attempts to push the Athenians back into the sea were unsuccessful and the Athenians were able to build a fort near Methana, threatening a number of Spartan allies.[92]

A reassessment of Delian League tribute occurred this year as well. The inscription thereof provides substantial epigraphic evidence for its members, their wealth, and also served the contemporary Athenian cause well. Athens brought in a total of between 1,460 and 1,500 talents; the increase in taxation also further Athenian unease as to her subjects' loyalty.[93]

424 BC[edit]

Athenian strategy in 424 BC, emboldened by Spartan unwillingness to continue its annual invasions of Attica, took a bolder strategy on land.[94]

Interpretations[edit]

Thucydides endows Periclean Athens with a defensive strategy: when the Peloponnesians invaded Attica, the Athenians would avoid battle and focus instead of maintaining their naval advantage, allowing them to resupply and to control, for taxation, their allies.[95] In Attica proper, the Athenians avoided hoplite battle but instead used cavalry to harass the Peloponnesian invaders. The goal of the Athenian strategy, per Thucydides' endorsement, seems to have been in forcing Spartan recognition of the status quo.[96] The passivity of the strategy may have been dictated by Athenian need to suppress revolts elsewhere in their empire.[97] On the other hand, Spartan strategy in Thucydides seems to have been premised on a rapidly decided war after a major land battle in Attica.[98] This had little effect and under the traditional view, because Sparta had little ability to force Athens to sally from the Long Walls and fight via siege, Sparta therefore had no plausible theory of victory. A number of explanatory interpretations have emerged.

Athenian passivity could be explained by recasting the conflict into one of status competition rather than Spartan fear of Athenian expansion.[99] J E Lendon, in the 2010 book Song of wrath, argues that Greek interstate rivalry was fought not for formal military victory but rather for the humiliation of the enemy and a reduction in their status.[100] The armed excursions into Attica or off ships onto Peloponnesian shores served to embarrass defenders and offer proportionate responses within the framework of status competition. These escalated into attacks on allies to demonstrate the hegemon's inability to defend them.[101]

Another view is that Pericles' defensive war plan is a Thuycididean invention meant to emphasise differences between Pericles and his Athenian successors.[102] Charlotte Schubert and Dewid Laspe, in a 2009 article in Historia, argue that Pericles' strategy was not, as Thucydides reports, mere passive defence, but rather to force Megara to rejoin the Delian League and win allies, especially Argos, on the Peloponnese.[103] If successful, Athens then would have assembled a sufficient forces to challenge Sparta on land and cut off Sparta's communications with many of its allies.[104] Such a strategic shift would have given Athens the numbers and position to force Spartan surrender.[105]

More radically, the pattern of Athenian attacks during the Archidamian War has been read to signal that the real war was actually between Athens and Corinth, rather than between Athens and Sparta as Thucydides reports. Giving Sparta the role of reluctant ally, forced into the field by its Corinthian treaty obligations and seeking to avoid cost, explains the ineffectiveness and hesitancy of Sparta's Attican expeditions, the longest of which lasted only forty days.[59] In this view, Spartan strategy was to do as little as necessary to meet its treaty obligations to its ally and Athenian strategy was instead to defeat Corinth before concluding a separate peace with Sparta.

Peace of Nicias[edit]

The Peace of Nicias, per its common modern term, was largely brought about by both the Athenian Nicias and his Spartan counterpart King Pleistoanax.[106]

Conditions[edit]

Melian dialogue[edit]

Silician expedition[edit]

Ionian or Decelean war[edit]

Outcome[edit]

Legacy[edit]

Sources[edit]

The main source on the Pelponnesian war is Thucydides' work, in English commonly known as the History of the Peloponnesian War, though he may have titled it Investigations or Composition. It discusses events starting from 478 through to 411 BC.[107] The work is traditionally divided into eight books; the eighth, however, is generally thought to be incomplete (it breaks off late in the summer of 411 BC). Some portions show anachronisms, which indicate composition after 404 BC and the end of the war, but reasons for the work's incompleteness are not known.[108] Much of Thucydides' narrative is believed to be reliable: he indicates where he inserts speculation, how he composed speeches based on how "[he] thought the several individuals or groups would have said what they had to say", and his uncertainty about the course of events.[109] After his exile from Athens in 423 BC he travelled substantially, gaining a wider perspective on the conflict, but also was cut off from first-hand observations of the Athenian assembly's deliberations.[110]

However, it is largely impossible to verify Thucydides' narrative, as he does not reveal his sources or methods and writes a selective narrative which largely ignores personal relations and events he believed unimportant.[111] For example, the importance of the Megarian Decree is heavily de-emphasised in the Thucydidean narrative; he may have done so because he believed the decree was irrelevant or to exonerate Pericles. However, other sources stress the importance of the decree in the choice for war, especially Aristophanes' plays and Plutarch's Pericles, which casts doubt on Thucydides' authorial choice.[112] Other times, in the narrative on the war itself, he ignores certain battles otherwise attested by epigraphic evidence and other literary sources; this has led to some scholarly suspicion that Thucydides may have omitted facts damaging to his narrative or analysis.[113]

Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian living in the 1st century BC, wrote a narrative which scholars believe was largely copied from a previous historian called Ephorus. Ephorus' narrative, as presented by Diodorus, poses substantial problems in chronology (largely from an attempt to match Roman consular years with years defined by Athens' eponymous archon). Much of Ephorus' narrative also was built on Thucydides' work, though other sources were also included, such as the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia written allegedly by Cratippus of Athens.[114] The other major historian is Xenophon, though the work Hellenica, though this narrative is now less well-regarded by scholars due to deficiencies in Xenophon's handling of material and claims of pro-Spartan bias.[115] Some Some fragments of Theopompus' Hellenica discuss the period 411 to 394 BC, but what survives is largely salacious rumour over the narrative at large. The much later biographies of Plutarch, writing in the first century AD, also provide biographies of a number of major actors during the war (Lysander, Themistocles, Aristides, Cimon, Pericles, Nicias, and Alcibiades), though scholars also use it cautiously due to Plutarch's somewhat poor judgement.[116]

Other sources of some use include comedies, the Atthides chronicling Athenian history, Aristotle's Athenian Constitution, and the Athenian Constitution of the Pseudo-Xenophon.[117] The comedic works help establish the social and cultural context of the war along with the state of public knowledge, while the Atthides and Athenian Constitution help establish chronology and political context at Athens.[118]

Contributions of epigraphy are also important: many Athenian inscriptions survive, such as those noting the tribute of the Delian League members.[119] Archaeology also has shed some light on the military history of the conflict. However, the limitations of the sources are clear inasmuch as almost all written accounts are from the perspective of Athens (including the name "Peloponnesian").[120]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Hornblower 2012b.

- ^ Cartledge 2012.

- ^ Bolmarcich 2008, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Bolmarcich 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 48–49; Lewis 1992b, p. 100.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 36, citing Arist. Ath. Pol., 23.5 placing it in the winter of 478–77 and Diod. Sic., 11.47 placing it in the winter of 477–76.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 235, 238.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 235–36.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 236; Rhodes 1992, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 238; Rhodes 1992, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 239.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 49.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 50.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 50, 52.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 51.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 54, 56.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, pp. 54, 61; Lewis 1992c, p. 127.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 57.

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 58 documents an epigraphic terminological transition through the 450s BC from the "Athenian alliance" to "cities which Athens rules".

- ^ Rhodes 1992, p. 59.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 279.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 243.

- ^ Lewis 1992c, p. 137.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 282–83.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 373.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 286; Lewis 1992d, pp. 375–76.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 286; Lewis 1992d, p. 376.

- ^ Parmeggiani 2018, p. 244.

- ^ Parmeggiani 2018, pp. 250–51, citing Diod. Sic., 12.39.4.

- ^ Another proposed ordering is Corinthian-Archidamnus followed by Athenian-Sthenelaidas. Bloedow 1981, p. 130 n. 4.

- ^ Bloedow 1981, p. 130.

- ^ Bloedow 1981, pp. 137–38.

- ^ a b Lewis 1992d, p. 378.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 286–87.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 379; Thuc., 1.140–141.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 379.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 306.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 370, citing Thuc., 2.1–7, 1.125.2, 2.12.3, 2.19.1.

- ^ Hornblower 2012a.

- ^ a b Powell 2018, p. 307.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 393–94.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 394.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 394–95.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 395.

- ^ a b Lewis 1992d, p. 396.

- ^ Cunha, Burke A (2004-03-01). "The cause of the plague of Athens: plague, typhoid, typhus, smallpox, or measles?". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 18 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00100-4. ISSN 0891-5520. PMC 7118959. PMID 15081502.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) Cunha suggested measles from differential diagnosis. - ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 331.

- ^ Papagrigorakis, Manolis J; et al. (2006-05-01). "DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 10 (3): 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2005.09.001. ISSN 1201-9712.

- ^ Biello, David (2006-01-25). "Ancient Athenian plague proves to be typhoid". Scientific American. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 331; Lewis 1992d, p. 396, , noting losses of 1,050 hoplites of 4,000.

- ^ Apollo was the god of plague. Powell 2018, p. 307.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 396–97.

- ^ a b Lewis 1992d, p. 398.

- ^ a b Lewis 1992d, p. 397.

- ^ a b Lewis 1992d, p. 399.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 401.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1992d, p. 402.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 403 n. 92.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 333. "The Athenian alliance appeared to be coming apart at the seams".

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 403.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 404.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 333; Lewis 1992d, p. 405.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 405.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 334.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 406.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 334; Lewis 1992d, p. 407.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 407–8.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 408.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 409.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 409; Lendon 2010, p. 477.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 409–10.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 410.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 410–11.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 411.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 412, 412 n. 112.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 412.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 413.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 334–35; Lewis 1992d, pp. 414–15.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 416.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 336, citing Thuc., 4.27ff.

- ^ Lewis 1992d.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 309, citing Thuc., 4.40.1.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 418.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 309.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 419.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 336 calls the Athenian decision to fight on a "mistake": "any peace that Sparta made to regain its men was likely to alienate its allies and foster the disintegration of the Peloponnesian League".

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 419–20.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 420.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 336.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 381.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 381–82.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, pp. 383, 386.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 389.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 217.

- ^ Lendon 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 218.

- ^ Schubert & Laspe 2009, p. 391.

- ^ Schubert & Laspe 2009, pp. 387–89.

- ^ Schubert & Laspe 2009, p. 389.

- ^ Schubert & Laspe 2009, pp. 389–90.

- ^ Powell 2018, p. 310.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, p. 1.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 4–5, citing Thuc., 1.21–22.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 326.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, pp. 286, 295–96.

- ^ Lewis 1992d, p. 380.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, p. 8. "Much recent work... has been based on a growing preference for Diodorus over Xenophon... the work [Xenophon's Hellenica] has had few whole-hearted admirers in recent years".

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 326; Lewis 1992a, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Lewis 1992a, p. 11.

- ^ Pomeroy 2018, p. 327.

Modern sources[edit]

- Bloedow, Edmund F (1981). "The speeches of Archidamus and Sthenelaidas at Sparta". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 30 (2): 129–143. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435752.

- Bolmarcich, Sarah (2008). "The date of the "Oath of the Peloponnesian League"". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 57 (1): 65–79. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 25598417.

- Fornara, Charles (2010). "The aftermath of the Mytilenian revolt". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 59 (2): 129–142. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 27809560.

- Hornblower, Simon; et al., eds. (2012). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Cartledge, Paul. "Peloponnesian League". In OCD4 (2012). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.4833

- Hornblower, Simon (2012a). "Archidamian War". In OCD4 (2012). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.686

- Hornblower, Simon (2012b). "Peloponnesian War". In OCD4 (2012). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.4834

- Jordović, Ivan (2011). "Aristotle on extreme tyranny and extreme democracy". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 60 (1): 36–64. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 29777247.

- Lendon, J E (2010). Song of wrath: the Peloponnesian War begins. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02280-9.

- Lewis, D M; et al., eds. (1992). The fifth century BC. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23347-X.

- Lewis, D M (1992a). "Sources, chronology, method". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 1–14.

- Rhodes, P J. "The Delian League to 449 BC". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 34–61.

- Lewis, D M (1992b). "Mainland Greece, 479–451 BC". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 96–120.

- Lewis, D M (1992c). "The Thirty Years' Peace". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 121–46.

- Lewis, D M (1992d). "The Archidamian War". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 370–432.

- Andrewes, A (1992a). "The peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 433–63.

- Andrewes, A (1992b). "The Spartan resurgence". In CAH2 5 (1992), pp. 464–98.

- Parmeggiani, Giovanni (2018). "How Sparta and its allies went to war: votes and diplomacy in 432–1 BC". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 67 (2): 244–255. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 45019289.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B; et al. (2018). Ancient Greece: a political, social, and cultural history (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-068691-8. LCCN 2016059031.

- Powell, Anton (2018). "Sparta's foreign – and internal – history, 478–403". In Powell, Anton (ed.). A companion to Sparta. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 291–319. ISBN 978-1-4051-8869-2. LCCN 2017011675.

- Robinson, Eric (2012). "Review of Lendon Song of Wrath". Classical Review. 62 (1): 217–219. doi:10.1017/S0009840X11003611. ISSN 0009-840X.

- Robinson, Eric (2014). "What happened at Aegospatami? Xenophon and Diodorus on the last battle of the Peloponnesian War". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 63 (1): 1–16. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 24433637.

- Schubert, Charlotte; Laspe, Dewid (2009). "Perikles' defensiver Kriegsplan: Eine thukydideische Erfindung?". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte (in German). 58 (4): 373–394. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 25598485.

Ancient sources[edit]

- Aristotle (1935). Constitution of the Athenians. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Rackham, H. Cambridge: Harvard University Press – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus (1933–67). Library of history. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Oldfather, C H; Sherman, C L; Welles, C Bradford; Geer, R M; Walton, F R. Harvard University Press – via LacusCurtius.

- Thucydides (1910). History of the Peloponnesian War. Everyman's Library. Translated by Crawley, Richard. London: J M Dent – via Perseus Classical Library.