User:HowardGrubbTeam2/sandbox

Howard Grubb[edit]

Early Life[edit]

Howard Grubb was born in Rathmines, Dublin in 1844. His father Thomas Grubb was the founder of the Grubb Telescope Company who Howard would later work for. After training to be a engineer, Howard joined his father's firm in 1864 and gained the reputation of a first-class producer of telescopes. Howard's main achievements lie in the development of optical telescopes, however, he is also praised for his work on periscopes and the reflector sight.[1]

Education[edit]

Howard Grubb went to school at North’s school in Rathmines, Dublin.[2] Howard then went on to attend Trinity College to study engineering. However, he was withdrawn to assist his father in his in casting a 4ft mirror for the Great Melbourne telescope and did not return. The Great Melbourne Telescope was the making of the Grubb enterprise as it symbolized a shift from amateur telescope manufacturing to government-sponsored work in observatories.[3]

Early Achievements[edit]

Grubb was elected Fellow of the Royal society in 1883 and of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1870. In 1887 he was knighted by Lord Lieutenant at Dublin castle. Sir Howard was a longtime member of the Royal Dublin Society, serving as Honorary Secretary from 1889 to 1893, and as Vice-President from 1893 to 1922. In 1912 he was awarded the medal of the Society, who was the third person to receive it.[4]

Influential friends, such as the physicist George Stokes and the Armagh astronomer Thomas Robinson, enabled Howard to secure a contract to supply a 15-inch refractor/18-inch reflector combination telescope to William Huggins who was one of the pioneers of astrophysics at the time. It was during this tenure with Huggins that lead to other contracts for the Royal observatory, Edinburgh and for Lord Lindsay’s private observatory at Dun Echt Scotland. Through Grubb’s connection with Lord Lindsay was how he became acquainted with astronomer David Gill, who was to become the main proponent for technical improvements to the firm’s telescope designs and a general booster of Grubb’s work.[2]

Career[edit]

Howard Grubb's greatest achievement was, firstly, the joint-construction with his father, Thomas Grubb, the Great Melbourne telescope. The other was the 27” telescope, years later, which can be found in the K&K Observatory, Vienna. [5]

48" Melbourne reflector[edit]

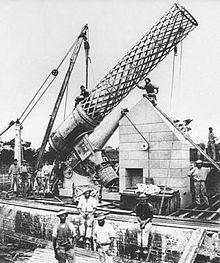

In Howard's third year at Trinity College, he left his education and joined the family business in 1866 to assist his father in the construction of a 48” equatorially mounted reflector in Melbourne, Australia. Construction was completed in Dublin, 1868 and was then transported to Melbourne, where it went into operation in August 1869. [6] Thomas Grubb retired from the firm in 1869, where Howard Grubb subsequently took over. Howard received assistance from the physicist, G.G. Stokes who was the Secretary of the Royal Society of London by offering guidance on challenging optical queries. [7] Stokes used his influence to convince the Royal Society to finance the lending of a 15” Grubb refractor to William Higgins. Higgins was the ground-breaker of spectral analysis in England at the time. [8] The success of lending the refractor influenced the demand for Howard to construct a 24” reflector for the Royal Observatory in Edinburgh, 1872. [9]

27" Telescope[edit]

Howard won the bid to commence construction of a 27” telescope to be operated in the Royal and Imperial K&K Observatory in Vienna. The scale of such a project lead to the ‘Optical and Mechanical Works’ factory being established in Rathmines. [10] At one point, it was the largest telescope the world had ever seen, the refractor along with seven 13” photographic telescopes for the Carte du Ciel projected a map of the heavens. [11]

War Time[edit]

By 1900, the Grubb Firm became predominantly focused on designing and manufacturing periscopes for submarines, as there was a heavy emphasis being placed on naval combat by the Royal Navy. [12] At the same time, the firm still continued to manufacture telescopes, notably a 26.5” for Johannesburg, SA. This telescope was far more technical and modern than previous ones constructed, with the first implementation of ball bearings. [13] As fears grew over damage to the supply chain with German submarines patrolling the Irish Sea, Howard made the decision to relocate the factory from Rathmines to England. By the time they had relocated the war had already ended. [14]

Later Career[edit]

During post-war depression, the demand for telescopes fell drastically, which lead to the Firm becoming liquidated. Sir Charles Parsons injected capital into the firm to keep it afloat. By now the firm had been renamed Grubb-Parsons, and went on to construct several more telescopes, with the ultimate being the 4.2m in diameter, William Herschel Telescope, which was inaugurated in 1987. [15] Howard left the Firm, having been taken over by Parsons. Howard Grubb’s son, Romney, remained for a period before being pushed out. The Firm shut down production in 1985, after over 150 years in business. [16]

Family Life[edit]

The Origin of the Grubb Family[edit]

The Grubb family can be traced back to John Grubbe (1620-1696), a Cromwellian settler in the southeast of Ireland. The Grubb family converted to Quakerism in 1676 by a wandering preacher named John Exham, and were thus amongst the earliest Irish members of the Society of Friends.[17] To be a Quaker involved considerable sacrifice, as in those days, in addition to the discrimination in official appointments and education applied to all those who were not members of the Church of Ireland, the Quakers were not prepared to take oaths – a great hinderance to them in business and legal manners.

Howard’s Parents[edit]

Thomas Grubb, according to Quaker records, was born in Waterford on 4th August 1800. Although his birth was registered with the Society of Friends, his marriage and the birth of his son Howard were not so it is probable that he did not remain an active member. He married Sarah Palmer (1798-1883) in Kilkenny in 1826. They had eight children in total, of which Howard, later Sir Howard Grubb, was the youngest son. He was born in 1844 in Rathmines, Dublin.

Thomas was the Chief Engineer at Bank of Ireland but always had a huge interest in the world of lenses. [18] In the 1830s, Thomas Grubb pioneered telescope manufacturing from his base close to Charlemont Bride on Dublin’s Grand Canal. [19] He founded the Grubb Telescope Company and was an innovator in the field of telescope making and optical design. One of his earliest instruments – the Markree telescope in the West of Ireland – was, for several years, the largest telescope in the world. [20] He was also responsible for the construction of the Great Melbourne Telescope. His firm grew rapidly over the years and became one of the leading telescope manufacturers in the world.

On 30th July 2018, The National Committee for Science and Engineering Commemorative Plaques, the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS) and the Construction Industry Federation (CIF) came together to erect a permanent marker commemorating Thomas Grubb’s achievements and his contribution to astronomy in Ireland and worldwide. The plaque is located at the site of Grubb’s first engineering works in Dublin – on Canal Road, Dublin 6. [21]

Howard Grubb’s Family[edit]

Howard Grubb married Mary Hester Walker on 5th September 1871 in St Peter’s Church (Church of Ireland). Mary was born in 1854 in New Orleans, of Irish parents. Her father, George Hamilton Walker, had been born in Kells, Co. Meath. Their first home was at 17 Leinster Square, Rathmines, close by the Optical Works. The six children of this marriage were Ethel (1872), Howard Thomas (1875), George Rudolph (1878), Romney Robinson (1879), Herman (1882) and Mary (1889). [22]

Thomas Grubb retired and handed over the Grubb Company to Howard in 1868 while he was studying to become a civil engineer at Trinity College Dublin. [23] Howard formalised the business and built a new factory to capitalise on the rapid growth of astrophotography and astrophysics. The remarkable family business operated in Rathmines, Dublin, for nearly a century.

Legacy[edit]

Professional Legacy[edit]

Following the production and introduction of the largest and best known telescopes of the Victorian era, the Grubb brothers landed themselves at the forefront of optical and mechanical engineering solidifying their legacy for centuries to come. The Grubbs - Howard and his father Thomas - spent decades supplying astronomical instruments to the world, with their work and inventions paving the way for how optical and mechanical engineering is carried out, executed and received. Their work also influenced the way in which many of the devices and telescopes used in these mechanisms and processes are utilized. [24]

In 1900, Howard Grubb introduced the reflector of reflex sight, a non-magnifying optical sight that uses a collimator to allow the viewer looking through the sight to see an illuminated image of a reticle or other pattern in front of them. This type of sight has come to be used on all kinds of devices from firearms to large fighter aircraft. It is also a fundamental element of head-up displays and continues to be the blueprint for many similar devices. Following this work, Grubb quickly gained the reputation for being a first class producer of telescopes and astronomical devices, while simultaneously inspiring many aspiring engineers. [25]

Under Howard Grubb - The Grubb Telescope Company, he gained an even greater reputation for quality optical instruments. Grubb assisted with the construction of a 48-inch reflector for Melbourne, completed in 1867 which is still widely used to this day in Australia and internationally. In 1914, Grubb moved his business to England, where in 1925, as the result of a merger, it became Sir Howard Grubb, Parsons & Company further widening the reach of his work. Grubb's astronomical work was also used for research and articles written about NASA, further displaying the legacy and scope of his work. [26]

Personal Legacy[edit]

In addition to his optical and mechanical engineering work, Grubb was awarded a Society award in the early 1990's (1912) for his contribution to the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. He was a longtime and loyal member of the Royal Dublin Society serving as honorary secretary and also vice-president, which both attributed to this award. He also received the Cunningham gold medal in 1881, and a Boyle medal. In 1913, he was given the tittle of scientific adviser as a result of his contribution to the Commissioners of Irish Lights. He was a member of the Royal Institute of Engineers of Ireland, and held an honorary degree in Master of Engineering.[27]

Grubb died in the year 1931, leaving six children and a vast amount of knowledge and instruments behind, along with the planning for a floating telescope. [28]

Later Life and Death[edit]

Submarine periscopes[edit]

After the 1900s, Grubb’s attention shifted from telescopes to periscopes for submarines for the Royal Navy [2]. The firm supplied 95% of the periscopes for submarines used by the British during the Great War [30].

The Great War effects[edit]

Transfer to St. Albans[edit]

During the Great War, no telescope work could be done, and it could not be completed until the end of the war [2]. The company was forced to move its headquarters to ensure the continuity of supply of periscopes [2]. The company was transferred from Dublin to St. Albans. It has been said that Grubb never really settled in England [31].

Post-war economic situation[edit]

The breakthrough of the Great War resulted in a stalemate in various of Grubb’s ongoing works, which eventually had detrimental effects for the firm [2]. The latter became economically weak and remained in a state of confusion even after the war was over [2]. Most of the financial support in the last years of the firm came only by the Russian Government, which had appointed various works to Grubb during the war period. He only managed to complete a few; the rest were finalised years after, under the new firm, owned by Sir Charles Parsons [2].

End of the firm[edit]

The firm went into liquidation in 1925. Grubb, being 81 years of age, retired from active participation in work [32]. A few months later, it was purchased by Sir Charles Parsons and relocated to Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It was renamed as Sir Howard Grubb Parsons and Company [2]. Once the company was sold to Parsons, Howard decided to return to his home town, in Dublin.

Last years at home[edit]

Death and funeral[edit]

He owned two houses, both overlooking the sea [2]. Grubb was very active both physically and mentally during his last years [31]. His wife Lady Mary died in April 1931, and he never really recovered from her loss. He died a few months later, the 16th of September, aged 87 [2].

His funeral took place on a Saturday morning at the Monkstown Parish Church. His coffin was transferred to Deans Grange Cemetery, the same one as his wife [33]. Those who attended the funeral were mainly family members and some significant personalities belonging to the societies he once belonged to [33].

Obituaries[edit]

He was subject of various obituaries, where he was presented as a good man, gentle, courteous and warm-hearted. In one of them, Mr. L.E. Steele, Vice-President of the Royal Dublin Society said “a talk with him was an intellectual treat” [32]

References[edit]

- ^ S.), Glass, I. S. (Ian (1997). Victorian telescope makers : the lives and letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Institute of Physics Pub.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hockey, Thomas (2007). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer. p. 447. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Adelman, Juliana (2015). "The Grubbs: 19th-century Irish stargazers". The Irish Times.

- ^ Burry, H. F. (1914). A History of the Royal Dublin Society.

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Adelman, J.(2015, July 9). The Grubbs: 19th Century Irish stargazers. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/the-grubbs-19th-century-irish-stargazers-1.2272676

- ^ Adelman, J.(2015, July 9). The Grubbs: 19th Century Irish stargazers. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/the-grubbs-19th-century-irish-stargazers-1.2272676

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Glass, I.S. (n.d.). THE GRUBB CONTRIBUTION TO TELESCOPE TECHNOLOGY. Retrieved from http://www.saao.ac.za/~isg/Venice.pdf

- ^ Ahlstrom, D.(2005, April 7). When Dublin provided windows to the stars. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/when-dublin-provided-windows-to-the-stars-1.430010

- ^ Ahlstrom, D.(2005, April 7). When Dublin provided windows to the stars. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/when-dublin-provided-windows-to-the-stars-1.430010

- ^ Grubb, T., Grubb, H., & Glass, I. S. (1997). Victorian Telescope Makers: The Lives and Letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing.

- ^ Hedderman, Z. (May 16th 2018). Double Take: The Plaque in Rathmines Celebrating Telescope Maker Howard Grubb. The Journal. Retrieved November 20th, 2018, from http://jrnl.ie/4006231

- ^ Dowling, E. & Breathnach, N. (2018, July 30th). Minister John Halligan Unveils Plaque to Commemorate 'Telescope-Maker Extraordinaire', Thomas Grubb. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Retrieved from https://www.dias.ie/ga/2018/07/30/30th-july-2018-minister-john-halligan-unveils-plaque-to-commemorate-telescope-maker-extraordinaire-thomas-grubb/

- ^ Grubb, T., Grubb, H., & Glass, I. S. (1997). Victorian Telescope Makers: The Lives and Letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing.

- ^ Dowling, E. & Breathnach, N. (2018, July 30th). Minister John Halligan Unveils Plaque to Commemorate 'Telescope-Maker Extraordinaire', Thomas Grubb. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Retrieved from https://www.dias.ie/ga/2018/07/30/30th-july-2018-minister-john-halligan-unveils-plaque-to-commemorate-telescope-maker-extraordinaire-thomas-grubb/

- ^ Grubb, T., Grubb, H., & Glass, I. S. (1997). Victorian Telescope Makers: The Lives and Letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing.

- ^ Grubb, R. (October 1995). Sir Howard Grubb. NLO News. Retrieved November 20th, 2018, from https://web.archive.org/web/20070205035540/http://www.projects.ex.ac.uk/nlo/news/nlonews/1995-01/9501-12.htm (archived 5 February 2007).

- ^ Glass, I. S. (1997). Victorian telescope makers: The lives and letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Pub.

- ^ Murray, J. (1906). Science progress. Oxford, Edinburgh. Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- ^ Glass, I. S. (1997). Victorian telescope makers: The lives and letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Pub.

- ^ “Grace's Guide" (2018, January 8). Howard Grubb. Retrieved from www.gracesguide.co.uk/Howard_Grubb.

- ^ Grubb, R. (1995, October). Sir Howard Grubb maker of the McClean 10 inch telescope. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20070205035540/http://www.projects.ex.ac.uk/nlo/news/nlonews/1995-01/9501-12.htm

- ^ a b "Funeral of Sir Howard Grubb". The Irish Times (1921 - Current File): 13. 1931 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Irish Times and The Weekly Irish Times.

- ^ "Sir Howard Grubb, F.R.S.". Nature. 128: 609–610. 10 October 1931. doi:10.1038/128609a0.

- ^ a b "Sir Howard Home: Special Interview". The Irish Times (1921 - Current File): 7. 1926 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ a b "Obituary Notices". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1 April 1932. doi:10.1098/rspa.1932.0049.

- ^ a b "The Late Sir Howard Grubb: Representation at the Funeral". The Irish Times (1921 - Current File). 1931 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.