User:Gog the Mild/Omaha Beach

| Omaha Beach | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Normandy landings, World War II | |||||||

Troops from the U.S. 1st Infantry Division landing on Omaha Beach | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 43,250 infantry | 7,800 infantry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000–5,000+ | 1,200 | ||||||

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors designated for the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded German-occupied France with the Normandy landings.[1] "Omaha" refers to an 8-kilometer (5 mi) section of the coast of Normandy, France, facing the English Channel, from east of Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes to west of Vierville-sur-Mer on the right bank of the Douve river estuary. Landings here were necessary to link the British landings to the east at Gold with the American landing to the west at Utah, thus providing a continuous lodgement on the Normandy coast of the Baie de Seine (Bay of the Seine river). Taking Omaha was to be the responsibility of United States Army troops, with sea transport, mine sweeping, and a naval bombardment force provided predominantly by the United States Navy and Coast Guard, with contributions from the British, Canadian and Free French navies.

The primary objective at Omaha was to secure a beachhead 5 miles (8 kilometers) deep, between Port-en-Bessin and the Vire river, linking with the British landings at Gold to the east, and reaching the area of Isigny to the west to link up with VII Corps landing at Utah. The untested American 29th Infantry Division, along with nine companies of U.S. Army Rangers redirected from Pointe du Hoc, assaulted the western half of the beach. The battle-hardened 1st Infantry Division was given the eastern half.

Opposing the landings was the German 352nd Infantry Division, detailed to defend a 32-mile (51 km) front. Of its 12,020 men, 6,800 were experienced combat troops. The German strategy was based on defeating any seaborne assault at the water line, and the defenses were mainly deployed in strongpoints along the coast.

The Allied plan called for initial assault waves of tanks, infantry, and combat engineer forces to reduce the coastal defenses, allowing larger ships to land in follow-up waves. But very little went as planned. Difficulties in navigation caused most of the landing craft to miss their targets throughout the day. The defenses were unexpectedly strong, and inflicted substantial casualties on landing U.S. troops. Under intense fire, the engineers struggled to clear the beach obstacles; later landings bunched up around the few channels that were cleared. Weakened by the casualties taken just in landing, the surviving assault troops could not clear the exits off the beach. This caused further problems and consequent delays for later landings. The original D-Day objectives were achieved over the following days.

Background[edit]

After the German Army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin began pressing his new allies for the creation of a second front in western Europe.[2] In late May 1942, the Soviet Union and the United States made a joint announcement that a "... full understanding was reached with regard to the urgent tasks of creating a second front in Europe in 1942."[3] However, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill persuaded U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to postpone the promised invasion as, even with U.S. help, the Allies did not at the time have adequate forces for such an activity.[4]

Instead of an invasion of France, the western Allies staged offensives in the Mediterranean Theatre of Operations, where British troops were already engaged. By May 1943, the campaign in North Africa had been won. The Allies then launched the invasion of Sicily in July and invaded the Italian mainland in September the same year. By then, Soviet forces were on the offensive and had won major victories at the battles of Stalingrad and Kursk. The decision to undertake a cross-channel invasion within the next year was taken at the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943.[5] Initial planning was constrained by the number of available landing craft, most of which were already committed in the Mediterranean and Pacific.[6] At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill promised Stalin that they would open the long-delayed second front in May 1944.[7]

The decision to undertake a cross-channel invasion of continental Europe within the next year was taken at the Trident Conference, held in Washington in May 1943.[8] A draft plan was accepted at the Quebec Conference in August 1943, with an invasion date of May 1, 1944.[9][10] General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF);[10] General Bernard Montgomery was named as commander of the 21st Army Group, which comprised all of the land forces involved in the invasion.[11] On September 10, 1943, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley took command of the US First Army, which was responsible for American ground forces.[citation needed] The need to acquire or produce extra landing craft and troop carrier aircraft for the expanded operation meant that the invasion was delayed to June. Production of landing craft was ramped up in late 1943 and continued into early 1944, and existing craft were relocated from other theaters.[12][6]

It was decided to land on a broad front in Normandy, which would permit simultaneous threats against the port of Cherbourg, coastal ports further west in Brittany, and an overland attack towards Paris and eventually into Germany.[13] The most serious drawback of the Normandy coast—the lack of port facilities—would be overcome through the development of artificial Mulberry harbours.[14] The final invasion plan called for five divisions to land from the sea during the first day of the invasion ("D-Day"), supported by three airborne divisions,[15] on a frontage of 50 miles (80 km) along the north coast of Normandy. The Americans would land at two sites, either side of the Vire estuary.[16] The area of beach that would become Omaha was originally known as X-Ray, but he two American landing sites were designated Omaha and Utah on 3 March 1944; the names were probably suggested by Bradley. The invasion coastline was divided into 24 sectors, with codenames using a spelling alphabet—from Able to William.[note 1] These sectors were further subdivided into beaches identified by the colors green, red, and white.[18][19] Eisenhower and Bradley selected the V Corps for the Omaha assault.[citation needed]

Opposing forces[edit]

German[edit]

The Calvados beaches of Normandy were defended by the 716th Static and 352nd Infantry divisions, with the Canadian landing zone defended by elements of the 716th. It was formed mostly from soldiers under 18 or over 35, comprising 7,771 combat troops in six battalions (as opposed to 9 or 12 battalions of Allied divisions).[20] While the 352nd was considered a first-rate division, the 716th was "accounted a better-than-average static division". These divisions generally had very few vehicles or tanks.[21]

American[edit]

[edit]

The landings would be supported by the largest invasion fleet in history – 7,016 vessels in total.[22] Task Force O, commanded by Rear Admiral John L. Hall Jr., was the naval component responsible for transporting the troops to land at Omaha across the channel and landing them on the beaches. The task force comprised four assault groups, a support group, a bombarding force, a minesweeper group, eight patrol craft, and three anti-submarine trawlers, numbering in total 1,028 vessels.[23] Assault groups O1 to O3, tasked with landing the main body of the assault, were organized along similar lines, with each comprising three infantry transports and varying numbers of tank landing ships (LST), Landing Craft Control (LCC), Landing Craft Infantry (LCI(L)), Landing Craft Tank (LCT), and Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM). Assault Group O4, tasked with landing the Rangers and the Special Engineer Task Force at Pointe du Hoc and Dog Green, comprised six smaller infantry transports.[24] Many of these vessels were British Royal Navy ships.[25]

The naval Support Group operated a mixture of gun, rocket, flak, tank, and smoke landing craft, totaling 67 vessels. The Minesweeper Group comprised 29 Royal Navy and 9 Royal Canadian Navy minesweepers.[24][26] Bombarding Force C comprised two battleships, three cruisers (two Free French and one Royal Navy), and 13 destroyers (three of which were provided by the Royal Navy).[27]

Opposing plans[edit]

Terrain[edit]

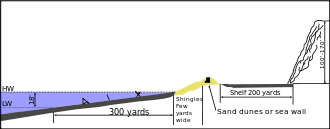

Omaha was bounded at either end by large rocky cliffs. The crescent-shaped beach presented a gently sloping tidal area averaging 300 yd (270 m) between low and high-water marks. Above the high-tide line was a bank of shingle 12 ft (4 m) high and up to 50 ft (15 m) wide in places. The western third of the shingle bank rested against a stone or wood sea wall which ranged from 5–13 ft (2–4 m) in height. Along the remainder of the beach the shingle lay against a low sand embankment. Behind the sand embankment and sea wall was a level shelf of sand, narrow at either end and up to 200 yd (180 m) wide in the center. Beyond this shelf rose steep escarpments or bluffs 30–50 yd (27–46 m) high, which dominated the beach and were cut into by small wooded valleys or draws at five points along the beach, codenamed from west to east D-1, D-3, E-1, E-3 and F-1.[28]

German plan[edit]

The German defensive preparations and the lack of any defense in depth indicated that their plan was to stop the invasion at the beaches.[29] Four lines of obstacles were constructed in the intertidal zone. The first, a non-contiguous line with a small gap in the middle of Dog White and a larger gap across the whole of Easy Red, was 250 yd (230 m) out from the highwater line and consisted of 200 Belgian Gates with mines lashed to the uprights. 30 yards (27 m) behind these was a continuous line of logs driven into the sand pointing seaward, every third one capped with an anti-tank mine. Another 30 yards (27 m) shoreward of this line was a continuous line of 450 ramps sloping towards the shore, also with mines attached and designed to force flat-bottomed landing craft to ride up and either flip or detonate the mine. The final line of obstacles was a continuous line of hedgehogs 150 yards (140 m) from the shoreline. The area between the shingle bank and the bluffs was both wired and mined, and mines were also scattered on the bluff slopes.[30]"Enemy Defenses". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. p. 23. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved 2007-06-10.</ref>

Coastal troop deployments, comprising five companies of infantry, were concentrated mostly at 15 strongpoints called Widerstandsnester ("resistance nests"), numbered WN-60 in the east to WN-74 near Vierville in the west, located primarily around the entrances to the draws and protected by minefields and wire.[31] Positions within each strongpoint were interconnected by trenches and tunnels. As well as the basic weaponry of rifles and machine guns, more than 60 light artillery pieces were deployed at these strongpoints. The heaviest pieces were located in eight gun casemates and four open positions while the lighter guns were housed in 35 pillboxes. Obsolete VK 30.01 (H) tank turrets (from a panzer development program) armed with 75mm L/24 gun were re-used in permanent fortified bunkers.[32] A further 18 anti-tank guns completed the disposition of artillery targeting the beach. Areas between the strongpoints were lightly manned with occasional trenches, rifle pits, and 85 machine-gun emplacements. No area of the beach was left uncovered, and the disposition of weapons meant that flanking fire could be brought to bear anywhere along the beach.[33][34]

Allied intelligence had identified the coastal defenders as a reinforced battalion (800–1000 men) of the 716th Infantry Division.[35] This was a static defensive division estimated to consist up to 50% of non-German troops, mostly Russians and Ukrainians, and German Volksdeutsche. The recently activated but capable 352nd Infantry Division was believed to be 20 miles (32 km) inland at Saint-Lô and was regarded as the most likely force to be committed to a counter-attack. As part of Rommel's strategy to concentrate defenses at the water's edge, the 352nd had been ordered forward in March,[36] taking over responsibility for the defense of the portion of the Normandy coast in which Omaha was located. As part of this reorganization, the 352nd also took under its command two battalions of the 726th Grenadier Regiment (part of the 716th Static Infantry Division) as well as the 439th Ost-Battalion, which had been attached to the 726th.[37] Omaha fell mostly within 'Coast Defense Sector 2', which stretched westward from Colleville and allocated to the 916th Grenadier Regiment, with the third battalion 726th Grenadier Regiment attached. Two companies of the 726th manned strongpoints in the Vierville area while two companies of the 916th occupied the St. Laurent area strongpoints in the center of Omaha. These positions were supported by the artillery of the first and fourth battalions of the 352nd Artillery Regiment (twelve 105 mm and four 150 mm howitzers respectively). The two remaining companies of the 916th formed a reserve at Formigny, two miles (3.2 kilometers) inland. East of Colleville, 'Coast Defense Sector 3' was the responsibility of the remainder of the 726th Grenadier Regiment. Two companies were deployed at the coast, one in the most easterly series of strongpoints, with artillery support provided by the third battalion of the 352nd Artillery Regiment. The area reserve, comprising the two battalions of the 915th Grenadier Regiment and known as 'Kampfgruppe Meyer', was located south-east of Bayeux outside the immediate Omaha area.[38]

American plan[edit]

The initial assault was to be made by two Regimental Combat Teams (RCTs), supported by two tank battalions, with two battalions of Rangers also attached. The infantry regiments were organized into three battalions each of around 1,000 men.[39] The tank battalions each consisted of 48 tanks, while the Ranger battalions each had a strength of around 400.[citation needed]

The 116th RCT of the 29th Infantry Division was to land two battalions on the western four beaches, to be followed 30 minutes later by the third battalion. Their landings were to be supported by the tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion; two of the units three companies swimming ashore in amphibious DD tanks and the remaining company landing directly onto the beach from assault craft. To the left of the 116th RCT the 16th RCT of the 1st Infantry Division was also to land two battalions with the third following 30 minutes after, at the eastern end of Omaha. Their tank support was to be provided by the 741st Tank Battalion, again two companies swimming ashore and the third landed conventionally. Three companies of the 2nd Ranger Battalion were to take a fortified battery at Pointe du Hoc, three miles (4.8 kilometers) to the west of Omaha. Meanwhile, C Company 2nd Rangers was to land on the right of the 116th RCT and take the positions at Pointe de la Percée. The remaining companies of 2nd Rangers and the 5th Ranger Battalion were to follow up at Pointe du Hoc if that action proved to be successful, otherwise they were to follow the 116th into Dog Green and proceed to Pointe du Hoc overland.[40]

The landings were scheduled to start at 06:30, "H-Hour", on a flooding tide, preceded by a 40-minute naval and 30-minute aerial bombardment of the beach defenses, with the DD tanks arriving five minutes before H-Hour. The infantry were organized into specially equipped assault sections, 32 men strong, one section to a landing craft, with each section assigned specific objectives in reducing the beach defenses. Immediately behind the first landings the Special Engineer Task Force was to land with the mission of clearing and marking lanes through the beach obstacles. This would allow the larger ships of the follow-up landings to get through safely at high tide. The landing of artillery support was scheduled to start at H+90 minutes while the main buildup of vehicles was to start at H+180 minutes. At H+195 minutes two further Regimental Combat Teams, the 115th RCT of the 29th Infantry Division and the 18th RCT of the 1st Infantry Division were to land, with the 26th RCT of the 1st Infantry Division to be landed on the orders of the V Corps commander.[41]

The objective was for the beach defenses to be cleared by H+2 hours, whereupon the assault sections were to reorganize, continuing the battle in battalion formations. The draws were to be opened to allow traffic to exit the beach by H+3 hours. By the end of the day, the forces at Omaha were to have established a bridgehead 5 miles (8.0 kilometers) deep, linked up with the British 50th Division landed at Gold to the east, and be in position to move on Isigny the next day, in order to link up with the American VII Corps landing at Utah to the west.[42]

Initial assault[edit]

Pre-landing[edit]

German movements[edit]

[edit]

Heavy Allied air attacks on the coastal defences commenced on 5 June at 23:30, with RAF Bomber Command targeting the primary coastal defences. This attack continued until 05:15, with 5,268 long tons (5,353 t) of bombs dropped by 1,136 sorties; this marked the largest attack by Bomber Command in terms of tonnage up to that point in the war. These attacks on the Atlantic Wall proved ineffective, with poor weather and visibility making it difficult to accurately hit the bunkers and turrets targeted. [43][a] The bombing left the defences on Omaha, and those on Gold and Juno to the east, virtually intact, yet did not damage Allied landing craft in the Channel, as many planners had feared it might.[44]

At 05:50 the planned naval bombardment began. The radar station at Pointe et Raz de la Percée was destroyed by two destroyers and Pointe-du-Hoc was targeted by the battleship USS Texas. The battleship USS Arkansas, a Free French cruiser and a further two destroyers bombarded Port-en-Bessin. The focus of the main naval bombardment was then switched to the beach defenses. The warships were supplemented by the fire of 36 M7 Priest howitzers, 34 tanks, 10 landing-craft-mounted 4.7-inch guns and the rockets of nine Landing Craft Tank (Rocket), the latter planned to hit the German defences as the assault craft were 300 yards (300 m) from the beach. At 06:00, 448 B-24 Liberators of the United States Army Air Forces attacked. However, with the skies overcast and under orders to avoid bombing the troops which were by then approaching the beach, the bombers overshot their targets and most bombs fell several miles inshore. The German 916th Grenadiers reported their positions to be under intense fire and some were very badly hit. Elsewhere the air and naval bombardment was not so effective, and the German beach defenses and supporting artillery remained largely intact.[45]

Later analysis of naval support during the pre-landing phase concluded that the navy had provided inadequate bombardment, given the size and extent of the planned assault.[46] D-Day planners had been concerned about the limited naval gunfire support plan for Omaha, especially in light of the tremendous naval gunfire support given to landings in the Pacific.[47] The historian Adrian R. Lewis postulates that American casualties would have been greatly reduced if a longer barrage had been implemented.[48]

I was the first one out. The seventh man was the next one to get across the beach without being hit. All the ones in-between were hit. Two were killed; three were injured. That's how lucky you had to be.

Captain Richard Merrill, 2nd Ranger Battalion.[49]

Battle for the beach[edit]

By 0830, the landings were called off for lack of space on the beach, as the Americans on Omaha Beach were unable to overcome German fortifications guarding the beach exits. Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commanding the American First Army, considered evacuating the survivors and landing the rest of the divisions elsewhere.[50][51]

German situation[edit]

Advance off the beach[edit]

"Are you going to lay there and get killed, or get up and do something about it?"

Unidentified lieutenant, Easy Red.[52]

The failure to clear beach obstacles forced subsequent landings to concentrate on Easy Green and Easy Red.[53] Where vehicles were landing, they found a narrow strip of beach with no shelter from enemy fire. Around 08:30, commanders suspended all such landings. This caused a jam of landing craft out to sea.[54]

Reinforcement regiments were due to land by battalion, beginning with the 18th RCT at 09:30 on Easy Red. The first battalion to land, 2/18, arrived at the E-1 draw 30 minutes late after a difficult passage through the congestion offshore. Casualties were light, though. Despite the existence of a narrow channel through the beach obstacles, the ramps and mines there accounted for the loss 22 LCVPs, 2 LCI(L)s and 4 LCTs. Supported by tank and subsequent naval fire, the newly arrived troops took the surrender at 11:30 of the last strong-point defending the entrance to the E-1 draw. Although a usable exit was finally opened, congestion prevented an early exploitation inland. The three battalions of the 115th RCT, scheduled to land from 10:30 on Dog Red and Easy Green, came in together and on top of the 18th RCT landings at Easy Red. The confusion prevented the remaining two battalions of the 18th RCT from landing until 13:00, and delayed the move off the beach of all but 2/18, which had exited the beach further east before noon, until 14:00. Even then, this movement was hampered by mines and enemy positions still in action further up the draw.[55]

By early afternoon, the strong-point guarding the D-1 draw at Vierville was silenced by the navy. But without enough force on the ground to mop up the remaining defenders, the exit could not be opened. Traffic was eventually able to use this route by nightfall, and the surviving tanks of the 743rd tank battalion spent the night near Vierville.[56]

The only artillery support for the troops making these tentative advances was from the navy. Finding targets difficult to spot, and in fear of hitting their own troops, the big guns of the battleships and cruisers concentrated fire on the flanks of the beaches. The destroyers were able to get in closer, and from 08:00 began engaging their own targets. Ordered to get as close in as possible, some approached within 1,000 yards (910 m), scraping the seabed and risking running aground.[57] The First Infantry Division Chief of Staff said that the Division would not have been able to move off the beach without effective naval gunfire.[58]

The advance of the 18th RCT cleared away the last remnants of the force defending the E-1 draw. When engineers cut a road up the western side of this draw, it became the main route inland off the beaches. With the congestion on the beaches thus relieved, they were re-opened for the landing of vehicles by 14:00. Further congestion on this route, caused by continued resistance just inland at St. Laurent, was bypassed with a new route, and at 17:00, the surviving tanks of the 741st tank battalion were ordered inland via the E-1 draw.[59]

The F-1 draw, initially considered too steep for use, was also eventually opened when engineers laid down a new road. In the absence of any real progress opening the D-3 and E-3 draws, landing schedules were revised to take advantage of this route, and a company of tanks from the 745th tank battalion were able to reach the high ground by 20:00.[60]

Approaches to the exits were also cleared, with minefields lifted and holes blown in the embankment to permit the passage of vehicles. As the tide receded, engineers were also able to resume their work of clearing the beach obstacles, and by the end of the evening, 13 gaps were opened and marked.[61]

Fighting inland[edit]

German defenses inland[edit]

While the coastal defenses had not turned back the invasion at the beach, they had broken up and weakened the assault formations struggling through them. The German emphasis on this Main Line of Resistance (MLR) meant that defenses further inland were significantly weaker, and based on small pockets of prepared positions smaller than company sized in strength. This tactic was enough to disrupt American advances inland, making it difficult even to reach the assembly areas, let alone achieve their D-Day objectives.[62]

American exploitation[edit]

Following the penetrations inland, a series confused andhard-fought small-unit actions pushed the American foothold to one and a half miles (2.4 kilometers) deep in the Colleville area to the east, less than that west of St. Laurent, and an isolated penetration in the Vierville area. Pockets of enemy resistance still fought on behind the American front line, and the whole beachhead remained under artillery fire. At 21:00 the landing of the 26th RCT completed the planned landing of infantry, but losses in equipment were high, including 26 artillery pieces, over 50 tanks, about 50 landing craft and 10 larger vessels.[63]

German response[edit]

Observing the build-up of shipping off the beach, and in an attempt to contain what were believed to be minor penetrations at Omaha, a battalion was detached from the 915th Regiment, which was being deployed against the British to the east. Along with an anti-tank company, this force was attached to the 916th Regiment and committed to a counterattack in the Colleville area in the early afternoon. It was stopped by "firm American resistance" and reported heavy losses.[64] The main threat was felt by the Germans to be the British beachheads to the east of Omaha, and these received the most attention from the German mobile reserves in Normandy.[65] The last reserve of the 352nd Division, an engineer battalion, was attached to the 916th Regiment in the evening. It was deployed to defend against the expected attempt to break out of the Colleville-St. Laurent beachhead established on the 16th RCT front. At midnight General Dietrich Kraiss, commander of the 352nd Division, reporting the total loss of men and equipment in the coastal positions, advised that he had sufficient forces to contain the Americans on D+1 but that he would need reinforcements thereafter; he was told that there were no more reserves available.[66]

End of the day[edit]

American situation[edit]

German situation[edit]

The German 352nd division suffered 1,200 killed, wounded and missing; about 20% of its strength.[66] Its deployment at the beach caused such problems that Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. First Army, at one stage considered evacuating Omaha,[67] while Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery considered the possibility of diverting V Corps forces through Gold.[68]

Aftermath[edit]

Only 100 of the 2,400 tons of supplies scheduled to be landed on D-Day were landed.[69] An accurate figure for casualties incurred by V Corps at Omaha on 6 June is not known; sources vary between 5,000 and over 6,000 killed, wounded, and missing,[70][71] with the heaviest losses incurred by the infantry, tanks and engineers in the first landings.[63] Only five tanks of the 741st Tank Battalion were ready for action the next day.[72] During the course of June 7, while still less than planned, 1,429 tons of stores were landed.[73]

Over the course of the next two days the original D-Day objectives were achieved. By the morning of June 9 the 1st Division had established contact with the British XXX Corps, thus linking Omaha with Gold to the east. By the morning of June 9 this regiment had taken Isigny and on the evening of the June 8 patrols established contact with the 101st Airborne Division, thus linking Omaha with Utah to the west.[74]

In the meantime, the original defender at Omaha, the 352nd Division, was being steadily reduced. By the morning of June 9 the division was reported as having been "...reduced to 'small groups'..." while the 726th Grenadier Regiment had "...practically disappeared."[75] By June 11 the effectiveness of the 352nd was regarded as "very slight",[76] and by June 14 the German corps command was reporting the 352nd as completely used up and needing to be removed from the line.[77]

Once the beachhead had been secured, Omaha became the location of one of the two Mulberry harbors, prefabricated artificial harbors towed in pieces across the English Channel and assembled just off shore. Construction of 'Mulberry A' at Omaha began the day after D-Day with the scuttling of ships to form a breakwater. By D+10 the harbor became operational when the first pier was completed; LST 342 docking and unloading 78 vehicles in 38 minutes. Three days later the worst storm to hit Normandy in 40 years began. It raged for three days and the harbor was so badly damaged that it was decided not to repair it; supplies being subsequently landed directly on the beach until sufficient port facilities were captured.[78] Over the 100 days following D-Day more than 1,000,000 tons of supplies, 100,000 vehicles and 600,000 men were landed at Omaha, and 93,000 casualties were evacuated.[79]

The remains of the coastal defenses can still be visited today.[80] At the top of the bluff overlooking Omaha near Colleville is the Normandy American cemetery containing 9,388 military burials.[81]

Notes, citations and sources[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Gal Perl Finkel, 75 years from that long day in Normandy – we still have something to learn, The Jerusalem Post, June 12, 2019.

- ^ Ford & Zaloga 2009, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Folliard 1942.

- ^ Ford & Zaloga 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Ford & Zaloga 2009, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Wilmot 1997, pp. 177–178, chart p. 180.

- ^ Churchill 1951, p. 404.

- ^ Ford & Zaloga 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Wilmot 1997, p. 170.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1989, p. 491.

- ^ Whitmarsh 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Balkoski 2005, pp. 19, 22.

- ^ Ambrose 1994, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Ford & Zaloga 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Whitmarsh 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Balkoski 2005, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Swanston & Swanston 2007, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Buckingham 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Caddick-Adams 2019, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Saunders 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Stacey 1966, p. 67.

- ^ Granatstein & Morton 1994, p. 23.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 48–49. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

TFOwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 48–49 & 54. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Operation Neptune" (PDF). Royal Navy. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 53. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Assault Plan". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. pp. 11–16. Archived from the original on 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Enemy Defenses". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. p. 20. Archived from the original on 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, p. 40. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, p. 42. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Wn67 Les Moulins - Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer". www.atlantikwall.co.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Enemy Defenses". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. p. 25. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Bastable, Jonathon (2006). Voices from D-Day. David & Charles. p. 132. ISBN 0-7153-2553-1.

- ^ "Enemy Defenses". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 20 September 1945. p. 26. CMH Pub 100-11. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Lt. Col. Fritz Ziegalmann (Chief of Staff of the 352ID). "The 352nd Infantry Division at Omaha Beach". Stewart Bryant. Archived from the original on 2007-04-28. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, p. 30. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, p. 33. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "16th Infantry Historical Records". National Archives (College Park, Maryland), Rg. 407, 301-INF (16)-0.3, Box 5909, Report of Operations file. 9 July 1945. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. p. 30. CMH Pub 100-11. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Assault Plan". Omaha Beachhead. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994 [20 September 1945]. pp. 30–33. CMH Pub 100-11. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 33. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ a b Stacey 1966, p. 93.

- ^ Stacey 1966, p. 94.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 50, 55–58, 59–61. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Amphibious Operations Invasion of Northern France Western Task Force, June 1944, Chapter 2–27". From Hyperwar, retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Michael Green, James D. Brown, War Stories of D-Day: Operation Overlord: June 6, 1944, p. 106.

- ^ Lewis, Adrian R. (2001). Omaha Beach: A Flawed Victory. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 2, 26. ISBN 0-8078-2609-X.

- ^ Bastable, Jonathon (2006). Voices from D-Day. David & Charles. p. 131. ISBN 0-7153-2553-1.

- ^ Hart 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Van Der Vat 2010, p. 100.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. pp. 75–77. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 79. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 80. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. pp. 82–85. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 95. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Badsey_p71was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tillman, Barrett (2004). Brassey's D-Day Encyclopedia: The Normandy Invasion A-Z. Washington, DC: Brassey's. pp. 170–171. ISBN 1-57488-760-2.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 104. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 106. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 102. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Harrison, Gordon A. (1951). "Cross-Channel Attack". Historical Division, War Department. p. 326. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ a b "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 109. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Harrison, Gordon A. (1951). "Cross-Channel Attack". Historical Division, War Department. p. 330. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ Harrison, Gordon A. (1951). "Cross-Channel Attack". Historical Division, War Department. p. 332. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ a b Harrison, Gordon A. (1951). "Cross-Channel Attack". Historical Division, War Department. p. 334. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ^ Badsey, Stephen; Bean, Tim (2004). Omaha Beach. Sutton Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 0-7509-3017-9.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 87. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 108. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Balkoski, Joseph (2004). Omaha Beach. US: Stackpole Books. pp. 350–352. ISBN 0-8117-0079-8.

- ^ Citino, Robert M. (2017). The Wehrmacht's Last Stand: The German Campaigns of 1944–1945. Kansas: University Press of Kansas. p. 135. ISBN 9780700624942.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 96–97. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ Badsey & Bean 2004, pp. 87, 92–95, 97–100. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBadseyBean2004 (help)

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 147. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 149. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Omaha Beachhead". Historical Division, War Department. 20 September 1945. p. 161. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "A Harbor Built from Scratch". Archived from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Bridge to the Past—Engineers in World War II". US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ Badsey, Stephen; Bean, Tim (2004). Omaha Beach. Sutton Publishing. pp. 12, 128–184. ISBN 0-7509-3017-9.

- ^ American Battle 2019.

Sources[edit]

- American Battle Monuments Commission. "Sailor Accounted for from World War II to be Buried Next to Twin Brother with Full Military Honors at Normandy American Cemetery, France". abmc.gov. American Battle Monuments Commission. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Badsey, Stephen; Bean, Tim (2004). Omaha Beach. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3017-9.

- Buckingham, William F. (2004). D-Day: The First 72 Hours. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2842-0.

- Caddick-Adams, Peter (2019). Sand & Steel: A New History of D-Day. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-1-84794-8-281.

- Hart, Russell (2003). The Second World War, Vol. 6: Northwest Europe 1944—1945. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-415-96850-8.

- Swanston, Alexander; Swanston, Malcolm (2007). The Historical Atlas of World War II. London: Cartographica Press. ISBN 978-1-84573-240-0.

- Trigg, Jonathan (2019). D-Day through German Eyes: How the Wehrmacht Lost France. Stroud UK: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-8931-9.

- Van Der Vat, Dan (2010). D-Day: The Greatest Invasion-A People's History. Madison Press Books. ISBN 978-1-897330-27-2. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).