User:Fowler&fowler/History of the Pakistan region

- This article is about history of the Pakistan region prior to 1947. For the post-1947 history, please see History of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The history of Pakistan—which for the period preceding the country's creation in 1947[1] is shared with those of Afghanistan, India, and Iran—traces back to the beginnings of human life in South Asia.[2] Spanning the western expanse of the Indian subcontinent and the eastern borderlands of the Iranian plateau, the region of present-day Pakistan served both as the fertile ground of some of South Asia's major civilizations and as the gateway to the Middle East and Central Asia.[3]

Pakistan is home to some of the most important sites of archaeology, including the earliest palaeolithic hominid site in South Asia in the Soan River valley.[4] Situated on the first coastal migration route of anatomically modern Homo sapiens out of Africa, the region was inhabited early by modern humans.[5] The 9,000-year history of village life in South Asia goes back to the Neolithic (7000—4300 BCE) site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan,[6] and the 5,000-year history of urban civilization in South Asia to the various sites of the Indus Valley Civilization, including Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.[7]

The ensuing millennia saw the region of present-day Pakistan absorb many influences—represented among others in the Vedic-Buddhist site of Taxila, the Greco-Buddhist site of Takht-i-Bahi, the 14th-century Islamic-Sindhi monuments of Thatta, and the 17th-century Mughal monuments of Lahore. From the late 18th century, the region was gradually appropriated by the East India Company—resulting in 90 years of direct British rule, and ending with the creation of Pakistan in 1947, through the efforts, among others, of its future national poet Allama Iqbal and its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

The Neolithic age[edit]

Mehrgarh[edit]

Mehrgarh, one of the most important Neolithic (7000 BCE to 3200 BCE) sites in archaeology, lies on the "Kachi plain of Baluchistan, Pakistan, and is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming (wheat and barley) and herding (cattle, sheep and goats) in South Asia."[8]. Mehrgarh was discovered in 1974 by an archaeological team directed by French archaeologist Jean-François Jarrige, and was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh—in the northeast corner of the 495-acre site—was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE-5500 BCE. Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BCE to 2600 BCE) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working. The site was occupied continuously until about 2600 BCE.[9]

In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence in human history for the drilling of teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. According to the authors, "Here we describe eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that dates from 7,500-9,000 years ago. These findings provide evidence for a long tradition of a type of proto-dentistry in an early farming culture."[10]

Mehrgarh is now seen as a precursor to the Indus Valley Civilization. "Discoveries at Mehrgarh changed the entire concept of the Indus civilization," according to Ahmad Hasan Dani, professor emeritus of archaeology at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, "There we have the whole sequence, right from the beginning of settled village life."[11] According to the Centre for Archaeological Research Indus Balochistan, Musée Guimet, Paris

| “ | ... the Kachi plain and in the Bolan basin (are) situated at the Bolan peak pass, one of the main routes connecting southern Afghanistan, eastern Iran, the Balochistan hills and the Indus valley. This area of rolling hills is thus located on the western edge of the Indus valley, where, around 2500 BCE, a large urban civilization emerged at the same time as those of Mesopotamia and the ancient Egyptian empire. For the first time in the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent, a continuous sequence of dwelling-sites has been established from 7000 – 500 BCE, (as a result of the) explorations in Pirak from 1968 to 1974; in Mehrgarh from 1975 to 1985; and of Nausharo from 1985 to 1996.[12] | ” |

Sometime between 2600 and 2000 BC, Mehrgarh was abandoned. Since the Indus civilisation was in its initial stages of development at that time, it has been surmised that the inhabitants of Mehrgarh migrated to the fertile Indus valley as Balochistan became more arid due to climatic changes.[12]

The Bronze age[edit]

Indus Valley civilization[edit]

The Indus Valley civilization (c. 3300-1700 BCE) was one of the most ancient civilizations, on the banks of Indus River. The Indus culture blossomed over the centuries and gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization around 3000 BCE. The civilization spanned much of what is today Pakistan, but suddenly went into decline around 1800 BCE. Indus Civilization settlements spread as far south as the Arabian Sea coast of India, as far west as the Iranian border, and as far north as the Himalayas. Among the settlements were the major urban centers of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, as well as Dholavira, Ganweriwala, Lothal, and Rakhigarhi. The Mohenjo-daro ruins were once the center of this ancient society. At its peak, some archeologists opine that the Indus Civilization may have had a population of well over five million.[13]

The Indus Valley civilisation has been tentatively identified as proto-Dravidian,[14] however, the Indus Valley script has not been definitively deciphered. To date, over a thousand cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the Indus River valley in Pakistan and western India.

The Kulli culture was a prehistoric culture in Southern Balochistan (Gedrosia), ca. 2500 - 2000 BCE. The culture was named after an archaeological site discovered by Sir Aurel Stein. Several settlement sites are known to have existed there however very few were excavated. Some of them have the size of small towns and are similar to those of the Indus Valley Civilization. The house are built of local stone. Agriculture was the economical base of this people. At several places dams were found, providing evidence for a highly developed water management. The pottery and other artifacts are similar to those of the Indus Valley Civilization and it not sure whether the Kulli culture is a local variation of the Indus Valley Civilization or an own culture complex.

Vedic Period[edit]

Although, the Indus Valley Civilization flourished in much of current-day Pakistan for over 1500 years, it disappeared abruptly around 1700 BCE. It has been conjectured that a cataclysmic earthquake might have been the cause, or, alternately, the drying up of the Ghagger-Hakra river. Soon thereafter, Indo-European speaking tribes from the Central Asia or the southern Russian steppes poured into the region.[15]

These so-called Aryans settled in the "Sapta Sindhu region, extending from the Kabul River in the north to the Sarasvati and Upper Ganges-Yamuna Doab in the south."[16] It was in this region that the hymns of the Rigveda were composed and the foundations of Hinduism laid. Mainstream scholarship places the Vedic culture lasting from the early second millennium BCE to the middle of the first millennium BCE, and the end of this period was marked by linguistic, cultural and political changes.[17] Although not much archaeological or epigraphic evidence of the migration exists in South Asia, similar migrations of Indo-European speaking people were recorded in other regions. For example, a treaty signed between the Hittites, who had arrived in Anatolia early in the second millennium BCE, and the Mitanni empire "invoked four deities—Indara, Uruvna, Mitira, and the Nasatyas (names that occur in the Rigveda as Indra, Varuna, Mitra, and the Asvins)".[16]

The city of Taxila, in present-day Pakistan, became important in Hinduism (and later in Buddhism). The city's original name was Takshashila (Sanskrit for “City of Cut-Stone” or “Rock of Taksha”), which was rendered by Greek writers as Taxila. "The great Indian epic Mahabharata was, according to tradition, first recited at Taxila at the great snake sacrifice of King Janamejaya, one of the heroes of the story."[18]

Persian and Greek invasion[edit]

Achaemenid empire[edit]

The lands of Pakistan were ruled by the Persian Achaemenid Empire (c.520 BCE) during the reign of Darius the Great until Alexander the Great's conquest. It became part of the empire as a satrapy that included the lands of present-day Pakistani Punjab, the Indus River, from the borders of Gandhara down to the Arabian Sea, and other parts of the Indus plain. According to Herodotus of Halicarnassus, it was the most populous and richest satrapy of the twenty satrapies of the empire. It was during the Persian rule that name India was coined. When the Indus River valley became the eastern most satrapy of Persians, they named it because of the Indus River. Vedic Aryans called the area Saptha Sindhu with the main river was called Sindhu. Persians had difficulty in pronouncing s, called it Hindu. As per the inscriptions of Darius, they called the satrapy Hindush. Greeks took this name from Persians and called the river Indus and the region India. Herodotus (490-425? BCE), in his book "The Histories", described this satrapy of Darius as India. Achaemenid rule lasted about 186 years. The Achaemenids used Aramaic script for the Persian language. After the end of Achaemenid rule, the use of Aramaic script in the Indus plain was diminished, although we know from Asokan inscriptions that it was still in use two centuries later. Other scripts, such as Kharosthi (a script derived from Aramaic) and Greek became more common after the arrival of the Macedonians and Greeks.

Alexander's empire[edit]

The interaction between Hellenistic Greece and Buddhism started when Alexander the Great conquered Asia Minor, the Achaemenid Empire and the lands of Pakistan in 334 BCE, defeating Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes (near modern-day Jhelum) and conquering much of the Punjab region. Alexander's troops refused to go beyond the Beas River — which today runs along part of the Indo-Pakistan border — and he took most of his army southwest, adding nearly all of the ancient lands in present-day Pakistan to his empire. Alexander created garrisons for his troops in his new territories, and founded several cities in the areas of the Oxus, Arachosia, and Bactria, and Macedonian/Greek settlements in Gandhara, such as Taxila, and Punjab. The regions included the Khyber Pass — a geographical passageway south of the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains — and the Bolan Pass, on a trade route connecting Drangiana, Arachosia and other Persian and Central Asia areas to the lower Indus plain. It is through these regions that most of the interaction between South Asia and Central Asia took place, generating intense cultural exchange and trade.

The Golden Age[edit]

From 3rd century BC to 5th century CE the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent came under continuous invasions of different Turko-Iranian, Bacterians, Sakas, Parthians, Kushans, and Huns.

It is surmised that Iranian tribes existed in western Pakistan during a very early age and that Pakhtun tribes were inhabitants around the area of Peshawar prior to the period of Alexander the Great as Herodotus refers to the local peoples as the "Paktui" and as a fearsome pagan tribe similar to the Bactrians. Iranian Balochi tribes did not arrive at least until the first millennium CE and would not expand as far as Sindh until the 2nd millennium.

Magadha Empire[edit]

Amongst the sixteen Mahajanapadas, the kingdom of Magadha rose greatly under a number of dynasties that reached a peak under the power of Asoka Maurya. The kingdom of Magadha had emerged as a major power following the subjugation of two neighbouring kingdoms, and possessed an unparalleled military.

Maurya Dynasty[edit]

The Mauryan dynasty lasted about 180 years, nearly as long as Achaemenid rule, and began with Chandragupta Maurya. Chandragupta Maurya lived in Taxila and met Alexander and had many opportunities to observe the Macedonian army there. He raised his own military using Macedonian tactics to overthrow the Nanda Dynasty in Magadha. Following Alexander's death on June 10, 323 BCE, his Diadochi (generals) founded their own kingdoms in Asia Minor and Central Asia. General Seleucus set up the Seleucid Kingdom, which included the Pakistan region. Chandragupta Maurya, taking advantage of the fragmentation of power that followed Alexander's death, invaded and captured the Punjab and Gandhara. Later, the Eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (third century–second century BCE).

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka the Great (273-232 BCE), is said to have been the greatest of the Mauryan emperors. Ashoka the Great was the ruler of the Mauryan empire from 273 BCE to 232 BCE. A convert to Buddhism, Ashoka reigned over most of South Asia and parts of Central Asia, from present-day Afghanistan to Bengal and as far south as Mysore. He converted to the Buddhist faith following remorse for his bloody conquest of the kingdom of Kalinga in Orissa. He became a great proselytiser of Buddhism and sent Buddhist emissaries to many lands. He set in stone the Edicts of Asoka. Nearly all of the Asokan edicts found today in Pakistan are written either in the Aramaic script (Aramiac had been the lingua franca of the Achaemenid Empire) or in Kharosthi, which, like other Indic scripts, is believed to be derived from Aramaic.

Greco-Buddhist period[edit]

Greco-Buddhism, sometimes spelled Græco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between the culture of Classical Greece and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 800 years in the area corresponding to modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, between the fourth century BCE and the fifth century CE. Greco-Buddhism influenced the artistic (and, possibly, conceptual) development of Buddhism, and in particular Mahayana Buddhism, before it was adopted by Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century AD, ultimately spreading to China, Korea and Japan.

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom[edit]

The invasion of northern India in 180 BCE by the king Demetrius (the son of theGreco-Bactrian king Euthydemus) went as far as Pataliputra and established an Indo-Greek kingdom that lasted nearly two centuries, until around 10 BCE. To the south, the Greeks captured Sindh and nearby Arabian Sea coastal areas. The invasion was completed by 175 BCE, and the Sungas were confined to the east, although the Indo-Greeks lost some territory in the Gangetic plain. Meanwhile in Bactria, the usurper Eucratides overcame the Euthydemid dynasty, killing Demetrius in battle.

Menander I was one of the Greek kings of the Indo-Greek Kingdom in ancient lands under modern day Pakistan from 155 to 130 BCE. He had been a general under King Demetrius, who was killed in battle. As a general, Menader drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming king shortly after his victory. Menander's territories covered the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of Bactria (from the areas of Panjshir and Kapisa) and extended to the modern Pakistani province of Punjab, with diffuse tributaries to the south and east, possibly even as far as Mathura. Sagala (modern Sialkot) became his capital and prospered greatly under Menander's rule. Menander is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors, among them Apollodorus of Artemita, who claimed that he was an even greater conqueror than Alexander the Great. Strabo[19] says Menander was one of the two Bactrian kings who extended their power farthest into South Asia. Sagala (modern Sialkot) became his capital and propered greatly under Menander's rule. His reign was long and successful (c.155 BCE - c.80 BCE). Generous findings of coins testify to the prosperity and extension of his empire. The Milinda Pañha, a classical Buddhist text, praises Menander, saying that "as in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness, and valour there was found none equal to Milinda in all India".[20]

Menander's empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, Strato II, disappeared around 10 CE. The Indo-Greeks suffered a new attack from the descendants of Eucratides around 125 BCE, as the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, was fleeing from the invasion of the Yuezhi in Bactria and trying to relocate in Gandhara. The Indo-Greeks retreated to their territories east of the Jhelum River as far as Mathura, and the two houses coexisted in the northern South Asia. Various kings ruled into the beginning of the first century CE, as petty rulers (such as Theodamas) and as administrators, after the conquests of the Scythians (see also Indo-Scythians), Parthians (see also Indo-Parthians) and Yuezhi, a Central Asian people possibly of Tocharian origins who founded the Kushan dynasty.

Indo-Greek Kingdom[edit]

The Indo-Greek Kingdom covered almost all regions of Pakistan from 180 BCE to around 10 CE, and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty Greek kings. The kingdom was founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius who invaded Pakistan and India in 180 BCE, creating an entity which seceded from the powerful Greco-Bactrian Kingdom centred in Bactria (today's northern Afghanistan).

The last known mention of an Indo-Greek ruler is suggested by an inscription on a signet ring of the 1st century CE in the name of a king Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, in modern Pakistan. No coins of him are known, but the signet bears in kharoshthi script the inscription "Su Theodamasa", "Su" being explained as the Greek transliteration of the ubiquitous Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah", "King").

Indo-Scythians[edit]

The Indo-Scythians are a branch of the Indo-European Sakas (Scythians), who migrated from southern Siberia into Bactria, Sogdiana, Kashmir and finally into Arachosia and Pakistan then India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled in northern India from Gandhara in Pakistan to Mathura.

Indo-Parthians[edit]

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was established during the 1st century CE, by a Parthian leader named Gondophares, in today's Afghanistan, Pakistan and Northern India. The Kingdom's capital was Taxila, (Pakistan)[1] Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine.

Kushan Empire[edit]

The kingdom was founded by King Heraios, and greatly expanded by his successor, Kujula Kadphises. Kadphises' son Vima Takto conquered territory now in India, but lost much of the western parts of the kingdom, including Gandhara, to the Parthian king Gondophares. The rule of Kanishka I, the fourth Kushan emperor, who flourished for at least 28 years from c. 127, was administered from a winter capital in Purushapura (now Peshawar in northwestern Pakistan) and a summer capital in Bagram (then known as Kapisa).

The rule of the Kushans linked the seagoing trade of the Indian Ocean with the commerce of the Silk Road through the long-civilized Indus Valley. At the height of the dynasty, the Kushans loosely oversaw a territory that extended to the Aral Sea through present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan into northern India. The loose unity and comparative peace of such a vast expanse encouraged long-distance trade, brought Chinese silks to Rome, and created strings of flourishing urban centers. Kanishka is renowned in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. This council is attributed with having marked the official beginning of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its scission with Nikaya Buddhism. Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Mahayana Buddhist texts translated into the high literary language of Sanskrit. Along with the Indian king Ashoka, the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda), and Harsha Vardhana, Kanishka is considered by Buddhism as one of its greatest benefactors.

The art and culture of Gandhara, at the crossroads of the Kushan hegemony, are the best known expressions of Kushan influences to Westerners. The interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures continued over several centuries until it ended in the fifth century CE with the invasions of the White Huns (see also Indo-Hephthalites), and later the expansion of Islam. During the remaining centuries before the coming of Islam in 711, the White Huns, Indo-Parthians, and Kushans shared control of what is today Pakistan with the Sassanid Persian empire which dominated much of western and southern Pakistan.

The Gupta Empire[edit]

The Gupta Empire arose in northern India around the second century CE and much of what is today Sindh made up the northwesternmost province of the empire. The era of the Guptas was marked by a local Hindu revival, although Buddhism continued to flourish.

Indo-Sassanians[edit]

The Sassanian empire of Persia, who were close contemporaries of the Guptas, began to expand into the north-western part of South Asia (now Pakistan), where they established their rule. The mingling of Indian and Persian cultures in this region gave birth to the Indo-Sassanian culture, which flourished in the western part of the Punjab and the areas now known in Pakistan as the North West Frontier Province and Balochistan. The last Hindu kingdom in this region, the Shahis, also may have arisen from this culture.

The Middle Age[edit]

Arab Rule[edit]

Before the birth of Islam in the 7th century the region was dominated by native rulers in the east and the Sassanid Persians in the west. Early in the 8th century (712 CE), and more than half a century after the defeat of the Sassanids at the hands of the Ummayad empire, a Syrian Muslim chieftain named Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the region and extended Umayyad rule to the Indus River. Qasim, a youth of 20, led a small force of 6,000 Syrian tribesmen and reached the borders of Kashmir within three years.

Muhammad Bin Qasim's conquests could not be sustained for very long. Umayyad rule, which extended from Lisbon, Portugal to Lahore, Punjab was spread too thin to be manageable. Upon Qasim's departure to Baghdad, the domain of Muslim rule shrank to Sindh and southern Punjab, where consolidation took place and conversion to Islam was widespread, especially amongst the native Buddhist majority. However, in regions north of Multan, Buddhists, Hindus and other non-Muslim groups remained numerous. During the 300-year period (712-1000), the Umayyad territory in South Asia was carved into two parts: the northern region comprising of the Punjab reverted back to the control of Hindu kingdoms, while the southern areas, comprising of Multan, Sindh, and Balochistan, which remained Muslim and owed allegiance to the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphs, became known as the administrative province of As-Sindh with capital at Al-Mansurah, 72 km north of present-day Hyderabad.[21]

[edit]

In 1001 Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni defeated Jeebal the king of Kabulistan and marched further into Peshawer and in 1005 made it the center for his forces. From this strategic location Mahmud was able to capture Panjab in 1007, Tanseer fell in 1014, Kashmir was captured in 1015 and Qanoch fell in 1017. By 1027 Sultan Mahmud had captured Pakistan and parts of northern India.

On 1010 Mahmud captured what is today the Ghor Province (Ghor) and by 1011 annexed Balochistan. Sultan Mahmud had already had relationships with the leadership in Balkh through marriage and its local emir Abu Nasr Mohammad offered his services to Sultan Mahmud and offered his daughter to Muhammad son of Sultan Mahmud. After Nasr’s death Mahmud brought Balkh under his leadership. This alliance greatly helped Mahmud during his expeditions into Pakistan and northern India.

In 1030 Sultan Mahmud fell gravely ill and died at the age of 59. Sultan Mahmud was an accomplished military commander and speaker as well as a patron of poetry, astronomy, and math. Mahmud had no tolerance for other religions however and only praised Islam. Universities were formed to study various subjects such as math, religion, the humanities and medicine were taught, but only within the laws of the Sharia. Islam was the main religion of his kingdom and the Perso-Afghan dialect of Dari language was made the official language.

Ghaznavid rule in Pakistan lasted for over one hundred and seventy five years from 1010 to 1187. It was during this period that Lahore assumed considerable importance as the eastern-most bastion of Muslim power and as an outpost for further advance towards the riches of the east. Apart from being the second capital—after Malik Ayaz was awarded the throne of Lahore—and later the only capital of the Ghaznavid kingdom, Lahore had great military and strategic significance. Whoever controlled this city could look forward to and be in a position to sweep the whole of East Punjab to Panipat and Delhi.

By the end of his reign, Mahmud's empire extended from Kurdistan in the west to Samarkand in the northeast, and from the Caspian Sea to the Yamuna. All of what is today Pakistan and Kashmir came under the Ghaznavid empire. The wealth brought back to Ghazni was enormous, and contemporary historians (e.g. Abolfazl Beyhaghi , Ferdowsi) give detailed descriptions of the building activity and importance of Lahore, as well as of the conqueror's support of literature.

Often reviled as a persecutor of Hindus (and in many cases Hindu temples were looted and destroyed) much of Mahmud's army consisted of Hindus and some of the commanders of his army were also of Hindu origin. Sonday Rai was the Commander of Mahmud's crack regiment and took part in several important campaigns with him. The coins struck during Mahmud's reign bore his own image on one side and the figure of a Hindu deity on the other.

Mahmud, as a patron of learning, filled his court with scholars including Ferdowsi the poet, Abolfazl Beyhaghi the historian (whose work on the Ghanavid Empire is perhaps the most substantive primary source of the period) and Al-Biruni the versatile scholar who wrote the informative Ta'rikh al-Hind ("Chronicles of India"). It was said that he spent over four hundred thousand golden dinars rewarding scholars. He invited the scholars from all over the world and was thus known as an abductor of scholars. During his rule, Lahore also became a great center of learning and culture. Lahore was called 'Small Ghazni' as Ghazni received far more attention during Mahmud's reign. Saad Salman, a poet of those times, also wrote about the academic and cultural life of Muslim Lahore and its growing importance.

The Islamic sultanates[edit]

Muhammad of Ghor[edit]

Muhammad Ghori was a Perso-Afghan conqueror from the region of Ghor in Afghanistan. Before 1160, the Ghaznavid Empire covered an area running from central Afghanistan east to the Punjab, with capitals at Ghazni, a city on the banks of Ghazni river in present-day Afghanistan, and at Lahore in present-day Pakistan. In 1160, the Ghorids conquered Ghazni from the Ghaznevids, and in 1173 Muhammad was made governor of Ghazni. He raided eastwards into the remaining Ghaznevid territory, and invaded Gujarat in the 1180s, but was rebuffed by Gujarat's Solanki rulers. In 1186-7 he conquered Lahore, ending the Ghaznevid empire and bringing the last of Ghaznevid territory under his control.

In 1191, he invaded the territory of Prithviraj III, the Chauhan Rajput Emperor of Ajmer and Delhi, who ruled much of present-day Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab, but was defeated at Tarain, near Bhatinda, by Govinda-raja of Delhi, Prithviraj's vassal. Being brought before Prithviraj he was pardoned and allowed to return to Ghor on promising no further trouble. The following year Muhammad Ghori assembled 120,000 horsemen and once again invaded the Kingdom of Ajmer. Muhammad's army met Prithviraj's army again at Tarain, and this time Muhammad was victorious; Govinda-raja was slain, Prithviraj captured and subsequently executed, and Muhammad advanced on Delhi, capturing it soon after. Within a year Muhammad controlled northern Rajasthan and the northern part of the Ganges-Yamuna Doab. Muhammad returned east to Ghazni to deal with the threat to his eastern frontiers from the Turks and Mongols, but his armies, mostly under Turkish generals, continued to advance through northern India, raiding as far east as Bengal.

Muhammad returned to Lahore after 1200 to deal with a revolt of the Rajput Ghakkar tribe in the Punjab. He suppressed the revolt, but was killed during a Ghakkar raid on his camp on the Jhelum River in 1206. Upon his death, his most capable general, Qutb-ud-din Aybak took control of Muhammad Ghori's Indian conquests and declared himself the first Sultan of Delhi.

Delhi Sultanate[edit]

Muhammad's successors established the first dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, while the Mamluk Dynasty (mamluk means "slave" and referred to the Turkic slave soldiers who became rulers throughout the Islamic world) in 1211 (however, the Delhi Sultanate is traditionally held to have been founded in 1206) seized the reins of empire. The territory under control of the Muslim rulers in Delhi expanded rapidly. By mid-century, Bengal and much of central India was under the Delhi Sultanate. Several Turko-Afghan dynasties ruled from Delhi: the Mamluk (1211-90), the Khalji (1290-1320), the Tughlaq (1320-1413), the Sayyid (1414-51), and the Lodhi (1451-1526). As Muslims extended their rule into southern India, only the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar remained immune, until it too fell in 1565. Although some kingdoms remained independent of Delhi in the Deccan and in Gujarat, Malwa (central India), and Bengal, almost all of the area in Pakistan came under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate.

The sultans of Delhi enjoyed cordial relations with Muslim rulers in the Near East but owed them no allegiance. The sultans based their laws on the Quran and the sharia and permitted non-Muslim subjects to practice their religion only if they paid the jizya or head tax. The sultans ruled from urban centers--while military camps and trading posts provided the nuclei for towns that sprang up in the countryside. Perhaps the greatest contribution of the sultanate was its temporary success in insulating the South Asia from the potential devastation of the Mongol invasion from Central Asia in the thirteenth century, which nonetheless led to the loss of Afghanistan and western Pakistan to the Mongols (see the Ilkhanate Dynasty). The sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance resulting from the stimulation of Islam by Hinduism. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion left lasting monuments in architecture, music, literature, and religion. In addition it is surmised that the language of Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Dehli Sultanate period as a result of the mingling of Sanskritic prakrits and the Persian, Turkish, Arabic favored by the Muslim invaders of India. The sultanate suffered from the sacking of Delhi in 1398 by Timur (Tamerlane) but revived briefly under the Lodhis before it was conquered by the Mughals in 1526.

The Early Modern Period[edit]

During the start of the 16th to the 19th century CE saw the arrivals of the moghal empire, which played a huge role in the development of the region not only economically but also culturally.

The Mughal Empire[edit]

The arrival of people from the Central Asian nations such as the Turks and Mongols was a significant turning point in the history of present-day Pakistan. The Qalandars (wandering Sufi saints) from Central Asia, Persia and Middle East preached a mystical form of Islam that appealed to the Buddhist and Hindu populations of Pakistan. The concepts of equality, justice, spiritualness, and secularism of the Sufi strain of Islam greatly attracted the masses towards it. The Sufi orders or triqas were established gradually, over a period of centuries. Present-day Pakistan was a place of great cultural and religious diversity. The Muslim technocrats, bureaucrats, soldiers, traders, scientists, architects, teachers, theologians and sufis flocked from the rest of the Muslim world to Islamic Sultanate in South Asia. The Muslim Sufi missionaries played a pivotal role in converting the millions of native people to Islam.

The Mughals were the descendants of Persianized Central Asian Turks (with significant Mongol admixture) and would establish a formidable empire over the breadth of South Asia and beyond. The Mughal Empire included modern Pakistan and reached as far north as eastern Afghanistan and as far south as southern India. It was one of the three major Islamic empires of its day and sometimes contested its northwestern holdings such as Qandahar against invasions from the Uzbeks and the Safavid Persians. Although the first Mughal emperor Babur favored the cool hills of Kabul, his conquests would lay the foundations for a dynasty that would hold sway over South Asia for over two centuries. Most of his successors were capable rulers and during the Mughal period the Shalimar Gardens were built in Lahore (during the reign of Shah Jehan and the Badshahi Mosque was erected during the reign of Aurangzeb. However, Aurganzeb was a controversial emperor, who was accused for his persecution of those that refused to convert to Islam. Dangerous criminals were at times set free because they were Muslims.[22] The advent of a tax on Non-Muslims and the foreceful conversions of Hindu and Sikh communities in the Pakistan region created laid the building blocks for a region that was going to have a large Muslim majority.[22] Aurangzeb was also known for his desecration and destruction of particular symbolic Hindu temples as well as the execution of the 9th Guru of Sikhism. One notable emperor, Akbar the Great was both a capable ruler and an early proponent of religious and ethnic tolerance and favored an early form of multiculturalism.

Pakistan still bears architectural monuments built by the Mughal emperors. During the Mughal period, the cities of Delhi (present-day India) and Lahore (present-day Pakistan) were made the capitals of the empire. The Taj Mahal and other architectural marvels were the results of the growth of Islamic culture and rule over the South Asia. The Mughals also implemented federal regulations including taxation, social welfare reforms, justice, development of the transport and agricultural system and water canals. The mansabdar system gained prominence during the Mughal Empire and was used to implement a form of ranking military official and landowners throughout the empire and in many ways inspired similar systems in other major Islamic empires of the day such as the Ottoman Empire's tanzimat reforms.

Durrani Empire[edit]

In 1739 Nadir Shah attacked India and after defeating the Mughal Emperor Mohammed Shah claimed Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, Balochistan and Sind as provinces of his empire. Upon the death of Nadir Shah, one of his generals, a Pashtun named Ahmed Shah Abdali (also Ahmad Shah Durrani) established the kingdom of Afghanistan in 1747 and claimed Kashmir, Peshawar, Daman, Multan, Sindh and Punjab for his new state.

When the Abdali kingdom weakened early in the 19th century due to internecine warfare, an independent kingdom arose in western Punjab headed by the Sikh leader Ranjit Singh. (The British, who had established their control over Delhi in 1803, warned Ranjit Singh not to attempt to impose his authority on the Sikh chieftains of East Punjab, beyond the Sutlej river.) In the south, the province of Sind, had begun to assert its independence from the waning days of Mughal emperor Aurengzeb's rule, and a succession of semi-independent dynasties under the Daudpotas, Kalhoras and Talpurs was to rule over this province until the British conquest in 1843 AD. Meanwhile, most of Balochistan came under the sphere of influence of the Khan of Kalat, except for a few coastal cities such as Gwadar which were controlled by the Sultan of Oman.

The Punjab[edit]

In the early 19th century, the Mughal empire and the Afghan Durrani empire weakened in power. Taking advantage of the situation, Sikhs conquered most of the Punjab, and parts of Kashmir and Eastern Afghanistan. Sikh warrior Ranjit Singh defeated the Afghans and took the title of Maharaja (High King) of the Punjab and eventually sovereign of the Sikh empire, stretching from within the shadows of Delhi to beyond Peshawar, with his capital at Lahore. It was also the last territory of South Asia to fall to the British Empire mainly due to the betrayal by its top Dogra Generals, during the two bloody Anglo-Sikh wars in 1845-6 and 1848-49. The outcome was a very narrow victory for the British resulting in the annexition of the Punjab and the fall of Sikh rule.

Colonial era[edit]

During the middle of the second millennium, several European countries, such as Great Britain, Portugal, Holland and France were initially interested in trade with South Asian rulers including the Mughals and leaders of other independent Kingdoms. The Europeans took advantage of the fractured kingdoms and the divided rule to colonize the country. Most of India came under the crown of the British Empire in 1857 after a failed insurrection, popularly known as the First War of Indian Independence, against the British East India Company by Bahadur Shah Zafar. Present-day Pakistan remained part of British South Asia until August 14, 1947.

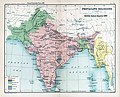

Maps of the Region 1765-1909[edit]

All but one maps in this section are taken from the Imperial Gazetteer of India, published by Oxford University Press in 1909. The colors marked "Muhammadan" (i.e. "Muslim") and "Hindu" in the maps of 1765, 1805, 1837, and 1857, indicate kingdoms whose rulers (and not necessarily the majority of their populations) practised those faiths.

-

1765. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan 1765, during the reign of Ahmad Shah Durrani.

-

1793. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan 1793, at the beginning of the reign of Zaman Shah Durrani.

-

1805. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan 1805, after more expansion of the Sikh Kingdom in Punjab.

-

1837. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan in 1837, during the height of Ranjit Singh's reign in Punjab.

-

1857. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan in 1857, just before the onset of direct rule by Great Britain.

-

1909. Map of the region and environs of present-day Pakistan in 1909, as a part of the British Indian Empire.

-

1909 Prevailing Religions, Map of British Indian Empire, 1909, showing the prevailing majority religions of the population for different districts.

-

1909 Percentage of Muslims, Map of British of Indian Empire, 1909, showing percentage of Muslims in different districts.

The Anglo-Afghan wars and the Great Game[edit]

The two Anglo-Afghan wars that involved Pakistan directly took place in 1839 and again in 1842 and 1878 and resulted in the eventual loss of Pashtun/Afghan territory to the expanding British Indian empire. Following the 2nd Anglo-Afghan war, a tenuous peace resulted between Afghanistan and the British empire based in India. Decades later, what is today western Pakistan would come to be annexed by the British.

For Afghan ruler Abdur Rahman Khan, delineating the boundary with India (through the Pashtun area) was far more significant, and it was during his reign that the Durand Line was drawn. Under pressure, Abdur Rahman agreed in 1893 to accept a mission headed by the British Indian foreign secretary, Sir Mortimer Durand, to define the limits of British and Afghan control in the Pashtun territories. Boundary limits were agreed on by Durand and Abdur Rahman before the end of 1893, but there is some question about the degree to which Abdur Rahman willingly ceded certain regions. There were indications that he regarded the Durand Line as a delimitation of separate areas of political responsibility, not a permanent international frontier, and that he did not explicitly cede control over certain parts (such as Kurram and Chitral) that were already in British control under the Treaty of Gandamak.

The Durand Line cut through both tribes and villages and bore little relation to the realities of topography, demography, or even military strategy. The line laid the foundation, not for peace between the border regions, but for heated disagreement between the governments of Afghanistan and British India, and later, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The issue revolves around the Pashtun nationalist movement known as Pashtunistan.

During much of the 19th century, the British and Russian Empires engaged in what came to be known as the Great Game as both sides intrigued over Afghanistan and western Pakistan. Often arming local Pashtun and Tajik tribesmen, both sides sought to undermine the other, while the rulers of Afghanistan were able to maintain some measure of independence in-spite of the loss of territories to the east to British India.

The British Raj[edit]

The first proponents of an independent Muslim nation began to appear in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century under the British Raj. Following the first War for Independence, the Indian National Congress was founded in 1885. Some Muslims felt the need to address the issue of the Muslim identity within India, leading to Sir Syed Amir Ali forming the Central National Muhammadan Association in 1877 to work towards the political advancement of the Muslims. The organisation declined towards the end of the nineteenth century but was replaced in 1906 by the All-India Muslim League. Although the League originally demanded constitutional guarantees for Muslims, several factors including sectarian violence prompted a reconsideration of the League's aims. The All India Muslim League was founded on the sidelines of the 1905 conference of the Muslim Anglo-Oriental Conference. This party was not, right until 1940, separatist. The idea of a separate nation was mooted in humor, satire and on the fringes of the political milieu.

Pakistan movement[edit]

By 1930, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who ultimately led the movement for a separate state, had despaired of Indian politics and particularly of getting mainstream parties like the Congress (of which he was a member much longer than the League) to be sensitive to minority priorities. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that he felt that a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated South Asia. The Sindh Assembly passed a resolution making it a demand in 1935.

Iqbal, Jauhar and others then worked hard to draft Mohammad Ali Jinnah to lead the movement for this new nation. Jinnah later went on to become known as the Father of the Nation, with Pakistan officially giving him the title Quaid-e-Azam or "Great Leader".

Pakistan Resolution[edit]

In 1940, Jinnah called a general session of the All India Muslim League in Lahore to discuss the situation that had arisen due to the outbreak of the Second World War and the Government of India joining the war without taking the opinion of the Indian leaders. The meeting was also aimed at analyzing the reasons that led to the defeat of the Muslim League in the general election of 1937 in the Muslim majority provinces. Jinnah, in his speech, criticised the Congress and the nationalist Muslims, and espoused the Two-Nation Theory and the reasons for the demand for separate Muslim homelands. Sikandar Hayat Khan, the Chief Minister of the Punjab region, drafted the original Lahore Resolution, which was placed before the Subject Committee of the All India Muslim League for discussion and amendments. The resolution, radically amended by the subject committee, was moved in the general session by Shere-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Huq, the Chief Minister of Bengal, on 23 March and was supported by Choudhury Khaliquzzaman and other Muslim leaders. The Lahore Resolution ran as follows:

- That the areas where the Muslims are numerically in a majority as in the Northwestern and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute 'independent states' in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign.

The Resolution was adopted on 23 March, 1940.

Origin of Name[edit]

The name was coined by Cambridge student and Muslim nationalist Choudhary Rahmat Ali. He devised the word and first published it on January 28, 1933 in the pamphlet Now or Never [2] Archived 2008-04-20 at the Wayback Machine. He saw it as an acronym formed from the names of the "homelands" of Muslims in South Asia. (P for Punjab, A for the Afghan areas of the region, K for Kashmir, S for Sindh and tan for Balochistan, thus forming 'Pakstan.' An i was later added to the English rendition of the name to ease pronunciation, producing Pakistan.) The word also captured in the Persian language the concepts of "pak", meaning "pure", and "stan", meaning "land" or "home", thus giving it the meaning "Land of the Pure". All Arabic-speaking countries refer to Pakistan as Bakstaan (باکستان), as the Arabic language lacks the phoneme [p].

Partition of the British Indian Empire[edit]

As the British granted independence to their dominions in India in mid-August 1947, the two nations joined the British Commonwealth as self-governing dominions. The partition left Punjab and Bengal, two of the biggest provinces, divided between India and Pakistan. In the early days of independence, more than two million people migrated across the new border and more than one hundred thousand died in a spate of communal violence. Non-Muslims who lived in Pakistan were forced the leave the area, which was one major factor in causing a violent reaction amongst the populations of the newly founded nations. The partition also resulted in tensions over Kashmir leading to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Pakistan was created as the Dominion of Pakistan on 14 August 1947 after the end of British rule in, and partition of British India.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha. "Pakistan." World Book Encyclopedia Online Reference Center. 2007. <http://www.worldbook.com/wb/Article?id=ar410880 Archived 2006-11-10 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ Kenoyer, J. Mark, and Kimberly Heuston. 2005. The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. 176 pages. ISBN 0195174224.

- ^ Rendell, H.R., Dennell, R.W. and Halim, M. (1989) Pleistocene and Palaeolithic Investigations in the Soan Valley, Northern Pakistan. British Archaeological Reports International Series 544. Cambridge University Press. 364 pp., 110 figs.

- ^ Qamar, Raheel, Qasim Ayub, Aisha Mohyuddin, Agnar Helgason, Kehkashan Mazhar, Atika Mansoor, Tatiana Zerjal, Chris Tyler-Smith, and S. Qasim Mehdi. 2002. "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan." American Journal of Human Genetics. 70(5):1107-1124.

- ^ Jarrige, C., J.-F. Jarrige, R. H. Meadow and G. Quivron, (Eds.) 1995. Mehrgarh Field Reports 1975 to 1985 - From the Neolithic to the Indus Civilization. Karachi: Dept. of Culture and Tourism, Govt. of Sindh, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, France.

- ^ Kenoyer, J. Mark. 1998. The Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. (American Institute of Pakistan Studies). Oxford University Press. 264 pages. ISBN 0195779401

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh" Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine. Guide to Archaeology

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. 1996. "Mehrgarh." Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ Coppa, A. et al. 2006. "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population." Nature. Volume 440. 6 April, 2006.

- ^ Chandler, Graham. 1999. "Traders of the Plain." Saudi Aramco World.

- ^ a b The Centre for Archaeological Research Indus Balochistan, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques - Guimet

- ^ The Indus Civilization Archived 2007-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Irfan Habib, Tulika Books, 2003

- ^ Parpola, Asko. 1994. Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge University Press. 396 pages. ISBN 0521430798

- ^ Stein, Burton. 1998. A History of India. Basil Blackwell Oxford. ISBN 0195654463

- ^ a b "Early Vedic Period." 2007. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 20, 2007, from : Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Erdosy, George (ed). 1995. The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity (Indian Philology and South Asian Studies, Vol 1). Walter de Gruyter. 417 pages. ISBN 3110144476

- ^ Taxila. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 19, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ 11.11.1

- ^ Translation by T.W. Rhys Davids, 1890

- ^ Sindh. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 15, 2007, from: Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ a b Growth Under the Mughals

Additional References[edit]

- Allchin, Bridget and Raymond Allchin. 'The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- Baluch, Muhammad Sardar Khan. 'History of the Baluch Race and Baluchistan' (Stuttgart, Germany: Steiner Verlag, 1987).

- Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 'The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan' (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1994).

- Bhutto, Benazir. 'Daughter of the East' (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1988).

- Bosworth, Clifford E. 'Ghaznavids' (South Asia Books, 1992).

- Bryant, Edwin. 'The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Cohen, Stephen P. 'The Idea of Pakistan' (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute Press, 2004).

- Dupree, Louis. 'Afghanistan' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Elphinstone, Mountstuart. 'An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul and its Dependencies in Persia, Tartary, and India' (London 1815, New Dehli: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1998).

- Esposito, John L. 'The Oxford History of Islam' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Gasciogne, Bamber and Christina Gasciogne. 'A Brief History of the Great Moguls' (Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2000).

- Hardy, Peter. 'The Muslims of British India' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972).

- Hopkirk, Peter. 'The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia' (New York: Kodansha International, 1990).

- Iqbal, Muhammad. 'The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam' (Kazi Publications, 1999).

- Jaffrelot, Christophe. 'A History of Pakistan and Its Origins' (London: Anthem Press, 2002).

- Kenover, Jonathan Mark. 'Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Mallory, J.P. 'In Search of the Indo-Europeans' (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey. 'To the Frontier: A journey to the Khyber Pass' (New York: Henry Holt Company, 1984).

- Olmstead, A.T. 'History of the Persian Empire: Achaemenid period' (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1948).

- Reat, Ross. 'Buddhism: A History', (Jain Publishing Company, 1996).

- Sidkey, H. 'The Greek Kingdom of Bactria' (Ohio: University Press of America, 2000).

- Smith, Vincent. 'The Oxford History of India' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981).

- Tarn, W.W. 'Greeks in Bactria and India', (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

- Thackston, Wheeler M. 'The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Thapar, Romila. 'A History of India : Volume 1' (New York: Penguin Books, 1990).

- Welch, Stuart Cary. 'Imperial Mughal Painting' (New York: George Braziller, 1978).

- Wheeler, R.E.M. 'Five Thousand Years of Pakistan'. (London: Royal India and Pakistan Society, 1950).

- Wheeler, R.E.M. 'Early India and Pakistan: To Ashoka, v. 12' (London: Praeger, 1968).

- Wolpert, Stanley. 'Jinnah of Pakistan' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Ziring, Lawrence. 'Pakistan in the Twentieth Century: A Political History' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

External links[edit]

- History of Pakistan Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Story of Pakistan

- Pakistan on Encarta Archived 2007-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Coins and Antiquities of Pakistan- from the Waleed Ziad Collection