User:Fconaway/sandbox

| Fconaway/sandbox |

|---|

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease affecting primarily the liver, caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV).[1] The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer or life-threatening esophageal and gastric varices.[1]

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment and transfusions. An estimated 150–200 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C.[2][3][4] The existence of hepatitis C (originally "non-A non-B hepatitis") was postulated in the 1970s and proven in 1989.[5] Hepatitis C infects only humans and chimpanzees.[6]

The virus persists in the liver in about 85% of those infected. This persistent infection can be treated with medication: the standard therapy is a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin, with either boceprevir or telaprevir added in some cases. Overall, 50–80% of people treated are cured. Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant. Hepatitis C is the leading reason for liver transplantation, though the virus usually recurs after transplantation.[7] No vaccine against hepatitis C is available.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Acute infection[edit]

Hepatitis C infection causes acute symptoms in 15% of cases.[8] Symptoms are generally mild and vague, including a decreased appetite, fatigue, nausea, muscle or joint pains, and weight loss[9] and rarely does acute liver failure result.[10] Most cases of acute infection are not associated with jaundice.[11] The infection resolves spontaneously in 10-50% of cases, which occurs more frequently in individuals who are young and female.[11]

Chronic infection[edit]

About 80% of those exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection.[12] This is defined as the presence of detectable viral replication for at least six months. Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the initial few decades of the infection,[13] although chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue.[14] Chronic infection after several years may cause cirrhosis or liver cancer.[7] The liver enzymes are normal in 7-53%.[15]

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops.[16][17] Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver.[16] Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma.[18] About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years.[7][9] Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male gender.[9] In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 100-fold.[19] Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year.[7][9]

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy.[20] Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.[21] Late relapses after apparent cure have been reported, but these can be difficult to distinguish from reinfection.[15]

Extrahepatic complications[edit]

The most common problem due to hepatitis C but not involving the liver is mixed cryoglobulinemia (usually the type II form) - an inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels.[22][23] Hepatitis C is also associated with Sjögren's syndrome (an autoimmune disorder); thrombocytopenia; lichen planus; porphyria cutanea tarda; necrolytic acral erythema; insulin resistance; diabetes mellitus; diabetic nephropathy; autoimmune thyroiditis and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.[24][25] Thrombocytopenia is estimated to occur in 0.16% to 45.4% of people with chronic hepatitis C.[26] 20-30% of people infected have rheumatoid factor - a type of antibody.[27] Possible associations include Hyde's prurigo nodularis[28] and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.[14] Cardiomyopathy with associated arrhythmias has also been reported.[29] A variety of central nervous system disorders have been reported.[30] Chronic infection seems to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.[31]

Occult infection[edit]

Persons who have been infected with hepatitis C may appear to clear the virus but remain infected.[32] The virus is not detectable with conventional testing but can be found with ultra-sensitive tests.[33] The original method of detection was by demonstrating the viral genome within liver biopsies, but newer methods include an antibody test for the virus' core protein and the detection of the viral genome after first concentrating the viral particles by ultracentrifugation.[34] A form of infection with persistently moderately elevated serum liver enzymes but without antibodies to hepatitis C has also been reported.[35] This form is known as cryptogenic occult infection.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection.[36] It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV infection including those on haemodialysis or family members of people with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is under investigation.[37] The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular carcinoma.[34]

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low.[15] 40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C virus in the liver on biopsy.[38] How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.[39]

Virology[edit]

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a small, enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus.[7] It is a member of the Hepacivirus genus in the family Flaviviridae.[14] There are seven major genotypes of HCV, which are known as genotypes one to seven.[40] The genotypes are divided into several subtypes with the number of subtypes depending on the genotype. In the United States, about 70% of cases are caused by genotype 1, 20% by genotype 2 and about 1% by each of the other genotypes.[9] Genotype 1 is also the most common in South America and Europe.[7]

The half life of the virus particles in the serum is around 3 hours and may be as short as 45 minutes.[41][42] In an infected person, about 1012 virus particles are produced each day.[41] In addition to replicating in the liver the virus can multiply in lymphocytes.[43]

Transmission[edit]

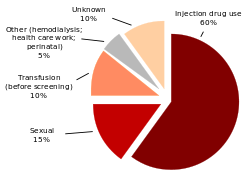

The primary route of transmission in the developed world is intravenous drug use (IDU), while in the developing world the main methods are blood transfusions and unsafe medical procedures.[44] The cause of transmission remains unknown in 20% of cases;[45] however, many of these are believed to be accounted for by IDU.[11]

Intravenous drug use[edit]

IDU is a major risk factor for hepatitis C in many parts of the world.[46] Of 77 countries reviewed, 25 (including the United States) were found to have prevalences of hepatitis C in the intravenous drug user population of between 60% and 80%.[12][46] Twelve countries had rates greater than 80%.[12] It is believed that ten million intravenous drug users are infected with hepatitis C; China (1.6 million), the United States (1.5 million), and Russia (1.3 million) have the highest absolute totals.[12] Occurrence of hepatitis C among prison inmates in the United States is 10 to 20 times that of the occurrence observed in the general population; this has been attributed to high-risk behavior in prisons such as IDU and tattooing with nonsterile equipment.[47][48]

Healthcare exposure[edit]

Blood transfusion, transfusion of blood products, or organ transplants without HCV screening carry significant risks of infection.[9] The United States instituted universal screening in 1992[49] and Canada instituted universal screening in 1990.[50] This decreased the risk from one in 200 units[49] to between one in 10,000 to one in 10,000,000 per unit of blood.[11][45] This low risk remains as there is a period of about 11–70 days between the potential blood donor's acquiring hepatitis C and the blood's testing positive depending on the method.[45] Some countries do not screen for hepatitis C due to the cost.[18]

Those who have experienced a needle stick injury from someone who was HCV positive have about a 1.8% chance of subsequently contracting the disease themselves.[9] The risk is greater if the needle in question is hollow and the puncture wound is deep.[18] There is a risk from mucosal exposures to blood; but this risk is low, and there is no risk if blood exposure occurs on intact skin.[18]

Hospital equipment has also been documented as a method of transmission of hepatitis C, including reuse of needles and syringes; multiple-use medication vials; infusion bags; and improperly sterilized surgical equipment, among others.[18] Limitations in the implementation and enforcement of stringent standard precautions in public and private medical and dental facilities are known to be the primary cause of the spread of HCV in Egypt, the country with highest rate of infection in the world.[51]

Sexual intercourse[edit]

Whether hepatitis C can be transmitted through sexual activity is controversial.[52] While there is an association between high-risk sexual activity and hepatitis C, it is not known whether transmission of the disease is due to drug use that has not been admitted to or sex (as risk factors).[9] The majority of evidence supports there being no risk for monogamous heterosexual couples.[52] Sexual practices that involve higher levels of trauma to the anogenital mucosa, such as anal penetrative sex, or that occur when there is a concurrent sexually transmitted infection, including HIV or genital ulceration, do present a risk.[52] The United States government recommends condom use to prevent hepatitis C transmission in only those with multiple partners.[53]

Body modification[edit]

Tattooing is associated with two to threefold increased risk of hepatitis C.[54] This can be due to either improperly sterilized equipment or contamination of the dyes being used.[54] Tattoos or piercings performed either before the mid-1980s, "underground," or nonprofessionally are of particular concern, since sterile techniques in such settings may be lacking. The risk also appears to be greater for larger tattoos.[54] It is estimated that nearly half of prison inmates share unsterilized tattooing equipment.[54] It is rare for tattoos in a licensed facility to be directly associated with HCV infection.[55]

[edit]

Personal-care items such as razors, toothbrushes, and manicuring or pedicuring equipment can be contaminated with blood. Sharing such items can potentially lead to exposure to HCV.[56][57] Appropriate caution should be taken regarding any medical condition that results in bleeding, such as cuts and sores.[57] HCV is not spread through casual contact, such as hugging, kissing, or sharing eating or cooking utensils.[57] Neither is it transmitted through food or water.[58]

Vertical transmission[edit]

Vertical transmission of hepatitis C from an infected mother to her child occurs in less than 10% of pregnancies.[59] There are no measures that alter this risk.[59] It is not clear when during pregnancy transmission occurs, but it may occur both during gestation and at delivery.[45] A long labor is associated with a greater risk of transmission.[18] There is no evidence that breast-feeding spreads HCV; however, to be cautious, an infected mother is advised to avoid breastfeeding if her nipples are cracked and bleeding,[60] or her viral loads are high.[45]

Diagnosis[edit]

There are a number of diagnostic tests for hepatitis C, including HCV antibody enzyme immunoassay or ELISA, recombinant immunoblot assay, and quantitative HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[9] HCV RNA can be detected by PCR typically one to two weeks after infection, while antibodies can take substantially longer to form and thus be detected.[20]

Chronic hepatitis C is defined as infection with the hepatitis C virus persisting for more than six months based on the presence of its RNA.[13] Chronic infections are typically asymptomatic during the first few decades,[13] and thus are most commonly discovered following the investigation of elevated liver enzyme levels or during a routine screening of high-risk individuals. Testing is not able to distinguish between acute and chronic infections.[18] Diagnosis in the infant is difficult as maternal antibodies may persist for up to 18 months.[39]

Serology[edit]

Hepatitis C testing typically begins with blood testing to detect the presence of antibodies to the HCV, using an enzyme immunoassay.[9] If this test is positive, a confirmatory test is then performed to verify the immunoassay and to determine the viral load.[9] A recombinant immunoblot assay is used to verify the immunoassay and the viral load is determined by a HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction.[9] If there are no RNA and the immunoblot is positive, it means that the person tested had a previous infection but cleared it either with treatment or spontaneously; if the immunoblot is negative, it means that the immunoassay was wrong.[9] It takes about 6–8 weeks following infection before the immunoassay will test positive.[14] A number of tests are available as point of care testing which means that results are available within 30 minutes.[61]

Liver enzymes are variable during the initial part of the infection[13] and on average begin to rise at seven weeks after infection.[14] The elevation of liver enzymes does not closely follow disease severity.[14]

Biopsy[edit]

Liver biopsies are used to determine the degree of liver damage present; however, there are risks from the procedure.[7] The typical changes seen are lymphocytes within the parenchyma, lymphoid follicles in portal triad, and changes to the bile ducts.[7] There are a number of blood tests available that try to determine the degree of hepatic fibrosis and alleviate the need for biopsy.[7]

Screening[edit]

It is believed that only 5–50% of those infected in the United States and Canada are aware of their status.[54] Testing is recommended in those at high risk, which includes injection drug users, those who have received blood transfusions before 1992,[62] and those with tattoos.[54] Screening is also recommended in those with elevated liver enzymes, as this is frequently the only sign of chronic hepatitis.[63] Routine screening is not currently recommended in the United States.[9] In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) added a recommendation for a single screening test for those born between 1945 and 1965.[64]

Prevention[edit]

As of 2011[update], no vaccine protects against contracting hepatitis C. However, there are a number under development and some have shown encouraging results.[65] A combination of harm reduction strategies, such as the provision of new needles and syringes and treatment of substance use, decrease the risk of hepatitis C in intravenous drug users by about 75%.[66] The screening of blood donors is important at a national level, as is adhering to universal precautions within healthcare facilities.[14] In countries where there is an insufficient supply of sterile syringes, medications should be given orally rather than via injection (when possible).[18]

Treatment[edit]

HCV induces chronic infection in 50–80% of infected persons. Approximately 40–80% of these clear with treatment.[67][68] In rare cases, infection can clear without treatment.[11] Those with chronic hepatitis C are advised to avoid alcohol and medications toxic to the liver,[9] and to be vaccinated for hepatitis A and hepatitis B.[9] Ultrasound surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended in those with accompanying cirrhosis.[9]

Medications[edit]

In general, treatment is recommended for those with proven HCV infection liver abnormalities;[9] As of 2010[update], treatments consist of a combination of pegylated interferon alpha and the antiviral drug ribavirin for a period of 24 or 48 weeks, depending on HCV genotype.[9] This results cure rates of between 70–80% for genotype 2 and 3, and 45 to 70% for other genotypes.[22] When combined with ribavirin, pegylated interferon-alpha-2a may be superior to pegylated interferon-alpha-2b, though the evidence is not strong.[69] Another agent, sofosbuvir, when combined with ribavirin, shows improved response rates in the 95% range for genotype 2.[22] This benefit is somewhat offset by a greater rate of adverse effects.[22]

Combining either boceprevir or telaprevir with ribavirin and peginterferon alfa improves antiviral response for hepatitis C genotype 1.[70][71][72] Adverse effects with treatment are common, with half of people getting flu like symptoms and a third experiencing emotional problems.[9] Treatment during the first six months is more effective than once hepatitis C has become chronic.[20] If someone develops a new infection and it has not cleared after eight to twelve weeks, 24 weeks of pegylated interferon is recommended.[20] In people with thalassemia, ribavirin appears to be useful but increases the need for transfusions.[73]

Surgery[edit]

Cirrhosis due to hepatitis C is a common reason for liver transplantion[20] though the virus usually (80–90% of cases) recurs afterwards.[7][74] Infection of the graft leads to 10–30% of people developing cirrhosis within five years.[75] Treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin post transplant decreases the risk of recurrence to 70%.[76]

Alternative medicine[edit]

Several alternative therapies are claimed by their proponents to be helpful for hepatitis C including milk thistle, ginseng, and colloidal silver.[77] However, no alternative therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in hepatitis C, and no evidence exists that alternative therapies have any effect on the virus at all.[77][78][79]

Prognosis[edit]

| no data <10 10–15 15–20 20–25 25–30 30–35 | 35–40 40–45 45–50 50–75 75–100 >100 |

The responses to treatment is measured by sustained viral response and vary by HCV C genotype. A sustained response occurs in about 40-50% in people with HCV genotype 1 given 48 weeks of treatment.[7] A sustained response is seen in 70-80% of people with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 with 24 weeks of treatment.[7] A sustained response occurs about 65% in those with genotype 4 after 48 weeks of treatment. The evidence for treatment in genotype 6 disease is sparse and what evidence there is supports 48 weeks of treatment at the same doses used for genotype 1 disease.[80] Successful treatment decreases the future risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 75%.[81]

Epidemiology[edit]

It is estimated that 150–200 million people, or ~3% of the world's population, are living with chronic hepatitis C.[2][3][4] About 3–4 million people are infected per year, and more than 350,000 people die yearly from hepatitis C-related diseases.[3] During 2010 it is estimated that 16,000 people died from acute infections while 196,000 deaths occurred from liver cancer secondary to the infection.[82] Rates have increased substantially in the 20th century due to a combination of intravenous drug abuse and reused but poorly sterilized medical equipment.[18]

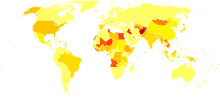

Rates are high (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, they are intermediate (1.5%-3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean, Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia and Central, Eastern and Western Europe; and they are low (<1.5%) in Asia Pacific, Tropical Latin America and North America.[4]

Among those chronically infected, the risk of cirrhosis after 20 years varies between studies but has been estimated at ~10%-15% for men and ~1-5% for women. The reason for this difference is not known. Once cirrhosis is established, the rate of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is ~1%-4% per year.[83] Rates of new infections have decreased in the Western world since the 1990s due to improved screening of blood before transfusion.[20]

In the United States, about 2% of people have hepatitis C,[9] with the number of new cases per year stabilized at 17,000 since 2007.[84] The number of deaths from hepatitis C has increased to 15,800 in 2008[85] and by 2007 had overtaken HIV/AIDS as a cause of death in the USA.[86] This mortality rate is expected to increase, as those infected by transfusion before HCV testing become apparent.[87] In Europe the percentage of people with chronic infections has been estimated to be between 0.13 and 3.26%.[88]

The total number of people with this infection is higher in some countries in Africa and Asia.[89] Countries with particularly high rates of infection include Egypt (22%), Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%).[3] It is believed that the high prevalence in Egypt is linked to a now-discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.[18]

History[edit]

In the mid-1970s, Harvey J. Alter, Chief of the Infectious Disease Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, and his research team demonstrated how most post-transfusion hepatitis cases were not due to hepatitis A or B viruses. Despite this discovery, international research efforts to identify the virus, initially called non-A, non-B hepatitis (NANBH), failed for the next decade. In 1987, Michael Houghton, Qui-Lim Choo, and George Kuo at Chiron Corporation, collaborating with Dr. D.W. Bradley at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, used a novel molecular cloning approach to identify the unknown organism and develop a diagnostic test.[90] In 1988, the virus was confirmed by Alter by verifying its presence in a panel of NANBH specimens. In April 1989, the discovery of HCV was published in two articles in the journal Science.[91][92] The discovery led to significant improvements in diagnosis and improved antiviral treatment.[90] In 2000, Drs. Alter and Houghton were honored with the Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research for "pioneering work leading to the discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C and the development of screening methods that reduced the risk of blood transfusion-associated hepatitis in the U.S. from 30% in 1970 to virtually zero in 2000."[93]

Chiron filed for several patents on the virus and its diagnosis.[94] A competing patent application by the CDC was dropped in 1990 after Chiron paid $1.9 million to the CDC and $337,500 to Bradley. In 1994, Bradley sued Chiron, seeking to invalidate the patent, have himself included as a coinventor, and receive damages and royalty income. He dropped the suit in 1998 after losing before an appeals court.[95]

Society and culture[edit]

World Hepatitis Day, held on July 28, is coordinated by the World Hepatitis Alliance.[96] The economic costs of hepatitis C are significant both to the individual and to society. In the United States the average lifetime cost of the disease was estimated at 33,407 USD in 2003[97] with the cost of a liver transplant as of 2011[update] costing approximately 200,000 USD.[98] In Canada the cost of a course of antiviral treatment is as high as 30,000 CAD in 2003,[99] while the United States costs are between 9,200 and 17,600 in 1998 USD.[97] In many areas of the world, people are unable to afford treatment with antivirals as they either lack insurance coverage or the insurance they have will not pay for antivirals.[100]

Research[edit]

As of 2011[update], there are about one hundred medications in development for hepatitis C.[98] These include vaccines to treat hepatitis, immunomodulators, and cyclophilin inhibitors, among others.[101] These potential new treatments have come about due to a better understanding of the hepatitis C virus.[102]

Special populations[edit]

Children and pregnancy[edit]

Compared with adults, infection in children is much less well understood. Worldwide the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in pregnant women and children has been estimated to 1-8% and 0.05-5% respectively.[103] The vertical transmission rate has been estimated to be 3-5% and there is a high rate of spontaneous clearance (25-50%) in the children. Higher rates have been reported for both vertical transmission (18%, 6-36% and 41%).[104][105] and prevalence in children (15%).[106]

In developed countries transmission around the time of birth is now the leading cause of HCV infection. In the absence of virus in the mother's blood transmission seems to be rare.[105] Factors associated with an increased rate of infection include membrane rupture of longer than 6 hours before delivery and procedures exposing the infant to maternal blood.[107] Cesarean sections are not recommended. Breast feeding is considered safe if the nipples are not damaged. Infection around the time of birth in one child does not increase the risk in a subsequent pregnancy. All genotypes appear to have the same risk of transmission.

HCV infection is frequently found in children who have previously been presumed to have non-A, non-B hepatitis and cryptogenic liver disease.[108] The presentation in childhood may be asymptomatic or with elevated liver function tests.[109] While infection is commonly asymptomatic both cirrhosis with liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma may occur in childhood.

Immunosuppressed[edit]

The prevalence of hepatitis C in immunosuppressed hosts is higher than the normal population particularly in those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, recipients of organ transplants and those with hypogammaglobulinemia.[110] Infection in these hosts is associated with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors), ed. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 551–2. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Gravitz L. (2011). "A smouldering public-health crisis". Nature. 474 (7350): S2–4. doi:10.1038/474S2a. PMID 21666731. S2CID 205065732.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b c d "Hepatitis C". World Health Organization (WHO). June 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Mohd Hanafiah, Khayriyyah; Groeger, Justina; Flaxman, Abraham D.; Wiersma, Steven T. (2013 Apr). "Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence". Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 57 (4): 1333–42. doi:10.1002/hep.26141. PMID 23172780. S2CID 16265266.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Houghton M (November 2009). "The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus". Journal of Hepatology. 51 (5): 939–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.08.004. PMID 19781804.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Shors, Teri (2011-11-08). Understanding viruses (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 535. ISBN 9780763785536.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rosen, HR (2011-06-23). "Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (25): 2429–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. PMID 21696309.

- ^ Maheshwari, Anurag; Ray, Stuart; Thuluvath, Paul J. (2008-07-26). "Acute hepatitis C". Lancet. 372 (9635): 321–32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2. PMID 18657711. S2CID 46648044.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Wilkins, T (2010-06-01). "Hepatitis C: diagnosis and treatment" (PDF). American Family Physician. 81 (11): 1351–7. PMID 20521755.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bailey, Caitlin (Nov 2010). "Hepatic Failure: An Evidence-Based Approach In The Emergency Department". Emergency Medicine Practice. 12 (4).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. p. 4. ISBN 9781461411918.

- ^ a b c d Nelson, Paul K.; Mathers, Bradley M.; Cowie, Benjamin; Hagan, Holly; Des Jarlais, Don; Horyniak, Danielle; Degenhardt, Louisa (2011-08-13). "Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews". Lancet. 378 (9791): 571–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. PMC 3285467. PMID 21802134.

- ^ a b c d Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9781461411918.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ray, Stuart C.; Thomas, David L. (2009). "Chapter 154: Hepatitis C". In Mandell, Gerald L.; Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0443068393.

- ^ a b c Nicot, F (2004). Occult hepatitis C virus infection: Where are we now?. p. Chapter 19. Liver biopsy in modern medicine. ISBN 978-953-307-883-0.

- ^ a b El-Zayadi, AR (2008 Jul 14). "Hepatic steatosis: a benign disease or a silent killer". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 14 (26): 4120–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4120. PMC 2725370. PMID 18636654.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Paradis, V.; Bedossa, P. (2008 Dec). "Definition and natural history of metabolic steatosis: histology and cellular aspects". Diabetes & Metabolism. 34 (6 Pt 2): 638–42. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(08)74598-1. PMID 19195624.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Alter, MJ (2007-05-07). "Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection" (PDF). World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 13 (17): 2436–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. PMC 4146761. PMID 17552026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mueller, S.; Millonig, G.; Seitz, H. K. (2009-07-28). "Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C: a frequently underestimated combination" (PDF). World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 15 (28): 3462–71. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3462. PMC 2715970. PMID 19630099.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f Ozaras, Resat; Tahan, Veysel (April 2009). "Acute hepatitis C: prevention and treatment". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 7 (3): 351–61. doi:10.1586/eri.09.8. PMID 19344247. S2CID 25574917.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Zaltron, S.; Spinetti, A.; Biasi, L.; Baiguera, C.; Castelli, F. (2012). "Chronic HCV infection: epidemiological and clinical relevance". BMC Infectious Diseases. 12 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2): S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-S2-S2. PMC 3495628. PMID 23173556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Dammacco, F.; Sansonno, D. (September 12, 2013). "Review Article: Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus–Related Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis". N Engl J Med. 369 (11): 1035–1045. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208642. PMID 24024840. Cite error: The named reference "NEJM2013" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Iannuzzella, F; Vaglio, A; Garini, G (May 2010). "Management of hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia". Am. J. Med. 123 (5): 400–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.038. PMID 20399313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Zignego, AL; Ferri, C; Pileri, SA; et al. (January 2007). "Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach". Digestive and Liver Disease. 39 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.008. PMID 16884964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ko, Huaibin M.; Hernandez-Prera, Juan C.; Zhu, Hongfa; Dikman, Steven H.; Sidhu, Harleen K.; Ward, Stephen C.; Thung, Swan N. (2012). "Morphologic features of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection". Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 740138. doi:10.1155/2012/740138. PMC 3420144. PMID 22919404.

- ^ Louie, K. S.; Micallef, J. M.; Pimenta, J. M.; Forssen, U. M. (January 2011). "Prevalence of thrombocytopenia among patients with chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 18 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01366.x. PMID 20796208. S2CID 21412295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Dammacco, Franco; Sansonno, Domenico; Piccoli, Claudia; Racanelli, Vito; d'Amore, Francesca Paola; Lauletta, Gianfranco (2000). "The lymphoid system in hepatitis C virus infection: autoimmunity, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and Overt B-cell malignancy". Seminars in Liver Disease. 20 (2): 143–57. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9613. PMID 10946420.

- ^ Lee, Michael R.; Shumack, Stephen (November 2005). "Prurigo nodularis: a review". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 46 (4): 211–18, quiz 219–20. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00187.x. PMID 16197418. S2CID 30087432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Matsumori, A (2006). "Role of hepatitis C virus in cardiomyopathies". Chronic Viral and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy. Ernst Schering Research Foundation Workshop. Vol. 55. pp. 99–120. doi:10.1007/3-540-30822-9_7. ISBN 978-3-540-23971-0. PMID 16329660.

- ^ Monaco, Salvatore; Ferrari, Sergio; Gajofatto, Alberto; Zanusso, Gianluigi; Mariotto, Sara (2012). "HCV-related nervous system disorders". Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 236148. doi:10.1155/2012/236148. PMC 3414089. PMID 22899946.

- ^ Xu, Jian-Hua; Fu, J. J.; Wang, X. L.; Zhu, J. Y.; Ye, X. H.; Chen, S. D. (2013 Jul 14). "Hepatitis B or C viral infection and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 19 (26): 4234–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4234. PMC 3710428. PMID 23864789.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sugden, Peter B.; Cameron, Barbara; Bull, Rowena; White, Peter A.; Lloyd, Andrew R. (2012 Sep). "Occult infection with hepatitis C virus: friend or foe?". Immunology and Cell Biology. 90 (8): 763–73. doi:10.1038/icb.2012.20. PMID 22546735. S2CID 23845868.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Carreño, V (2006 Nov 21). "Occult hepatitis C virus infection: a new form of hepatitis C". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 12 (43): 6922–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.2000. PMC 4087333. PMID 17109511.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Carreño García, V.; Nebreda, J. B.; Aguilar, I. C.; Quiroga Estévez, J. A. (2011 Mar). "[Occult hepatitis C virus infection]". Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 29 Suppl 3: 14–9. doi:10.1016/S0213-005X(11)70022-2. PMID 21458706.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pham, Tram N. Q.; Coffin, Carla S.; Michalak, Tomasz I. (2010 Apr). "Occult hepatitis C virus infection: what does it mean?". Liver International : Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 30 (4): 502–11. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02193.x. PMID 20070513. S2CID 205651069.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Carreño, Vicente; Bartolomé, J.; Castillo, I.; Quiroga, J. A. (2012 Jun 21). "New perspectives in occult hepatitis C virus infection". World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 18 (23): 2887–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2887. PMC 3380315. PMID 22736911.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Carreño, Vicente; Bartolomé, Javier; Castillo, Inmaculada; Quiroga, Juan Antonio (2008 May-Jun). "Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections". Reviews in Medical Virology. 18 (3): 139–57. doi:10.1002/rmv.569. PMID 18265423. S2CID 12331754.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scott, J. D.; Gretch, D. R. (2007 Feb 21). "Molecular diagnostics of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 297 (7): 724–32. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.724. PMID 17312292.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Robinson, JL (July 4, 2008). "Vertical transmission of the hepatitis C virus: Current knowledge and issues". Paediatr Child Health. 13 (6): 529–534. doi:10.1093/pch/13.6.529. PMC 2532905. PMID 19436425.

- ^ Nakano, T; Lau, GM; Lau, GM; et al. (December 2011). "An updated analysis of hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes based on the complete coding region". Liver Int. 32 (2): 339–45. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02684.x. PMID 22142261. S2CID 23271017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Lerat, Hervé; Hollinger, F. Blaine (2004 Jan 1). "Hepatitis C virus (HCV) occult infection or occult HCV RNA detection?". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1086/380203. PMID 14702146. S2CID 28523691.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pockros, Paul (2011). Novel and Combination Therapies for Hepatitis C Virus, An Issue of Clinics in Liver Disease. p. 47. ISBN 9781455771981.

- ^ Zignego, Anna Linda; Giannini, Carlo; Gragnani, Laura; Piluso, Alessia; Fognani, Elisa (2012 Aug 3). "Hepatitis C virus infection in the immunocompromised host: a complex scenario with variable clinical impact". Journal of Translational Medicine. 10: 158. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-10-158. PMC 3441205. PMID 22863056.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Maheshwari, Anurag; Thuluvath, Paul J. (February 2010). "Management of acute hepatitis C". Clinics in Liver Disease. 14 (1): 169–76, x. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.007. PMID 20123448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e Pondé, RA (February 2011). "Hidden hazards of HCV transmission". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 200 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1007/s00430-010-0159-9. PMID 20461405. S2CID 664199.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Xia, X.; Luo, J.; Bai, J.; Yu, R. (October 2008). "Epidemiology of HCV infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis". Public Health. 122 (10): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.014. PMID 18486955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Imperial, JC (June 2010). "Chronic hepatitis C in the state prison system: insights into the problems and possible solutions". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 4 (3): 355–64. doi:10.1586/egh.10.26. PMID 20528122. S2CID 7931472.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Vescio, M. F.; Longo, B.; Babudieri, S.; Starnini, G.; Carbonara, S.; Rezza, G.; Monarca, R. (April 2008). "Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 62 (4): 305–13. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.051599. PMID 18339822. S2CID 206989111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Marx, John (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1154. ISBN 9780323054720.

- ^ Day RA; Paul P; Williams B; et al. (November 2009). Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of Canadian medical-surgical nursing (Canadian 2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1237. ISBN 9780781799898.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Highest Rates of Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Found in Egypt". Al Bawaaba. 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ a b c Tohme RA, Holmberg SD (June 2010). "Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission?". Hepatology. 52 (4): 1497–505. doi:10.1002/hep.23808. PMID 20635398. S2CID 5592006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Hepatitis C Group Education Class". United States Department of Veteran Affairs.

- ^ a b c d e f Jafari, Siavash; Copes, Ray; Baharlou, Souzan; Etminan, Mahyar; Buxton, Jane (November 2010). "Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): e928–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.03.019. PMID 20678951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Hepatitis C" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Lock G; Dirscherl M; Obermeier F; et al. (September 2006). "Hepatitis C – contamination of toothbrushes: myth or reality?". J. Viral Hepat. 13 (9): 571–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00735.x. PMID 16907842. S2CID 24264376.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c "Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Wong T, Lee SS (February 2006). "Hepatitis C: a review for primary care physicians". CMAJ. 174 (5): 649–59. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1030034. PMC 1389829. PMID 16505462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Lam, N. C.; Gotsch, P. B.; Langan, R. C. (2010-11-15). "Caring for pregnant women and newborns with hepatitis B or C" (PDF). American Family Physician. 82 (10): 1225–9. PMID 21121533.

- ^ Mast EE (2004). "Mother-to-infant hepatitis C virus transmission and breastfeeding". Protecting Infants through Human Milk. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 554. pp. 211–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_18. ISBN 978-1-4419-3461-1. PMID 15384578.

- ^ Shivkumar, S (2012 Oct 16). "Accuracy of Rapid and Point-of-Care Screening Tests for Hepatitis C: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (8): 558–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00006. PMID 23070489. S2CID 5650682.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Moyer, Virginia A.; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2013 Jun 25). "Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID 23798026. S2CID 8563203.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Senadhi, V (July 2011). "A paradigm shift in the outpatient approach to liver function tests". Southern Medical Journal. 104 (7): 521–5. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31821e8ff5. PMID 21886053. S2CID 26462106.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA; et al. (August 2012). "Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965". MMWR Recomm Rep. 61 (RR-4): 1–32. PMID 22895429.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Halliday, John; Klenerman, Paul; Barnes, Eleanor (2011 May). "Vaccination for hepatitis C virus: closing in on an evasive target". Expert Review of Vaccines. 10 (5): 659–72. doi:10.1586/erv.11.55. PMC 3112461. PMID 21604986.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hagan, H.; Pouget, E. R.; Des Jarlais, D. C. (2011-07-01). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir196. PMC 3105033. PMID 21628661.

- ^ Torresi, Joseph; Johnson, Doug; Wedemeyer, Heiner (June 2011). "Progress in the development of preventive and therapeutic vaccines for hepatitis C virus" (PDF). Journal of Hepatology. 54 (6): 1273–85. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.040. PMID 21236312.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ilyas, Jawad A.; Vierling, John M. (August 2011). "An overview of emerging therapies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Clinics in Liver Disease. 15 (3): 515–36. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.002. PMID 21867934.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Awad T, Thorlund K, Hauser G, Stimac D, Mabrouk M, Gluud C (April 2010). "Peginterferon alpha-2a is associated with higher sustained virological response than peginterferon alfa-2b in chronic hepatitis C: systematic review of randomized trials". Hepatology. 51 (4): 1176–84. doi:10.1002/hep.23504. PMID 20187106. S2CID 19437977.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Foote BS, Spooner LM, Belliveau PP (September 2011). "Boceprevir: a protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (9): 1085–93. doi:10.1345/aph.1P744. PMID 21828346. S2CID 39593200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith LS, Nelson M, Naik S, Woten J (May 2011). "Telaprevir: an NS3/4A protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (5): 639–48. doi:10.1345/aph.1P430. PMID 21558488. S2CID 2886659.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB (October 2011). "An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases". Hepatology. 54 (4): 1433–44. doi:10.1002/hep.24641. PMC 3229841. PMID 21898493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alavian SM, Tabatabaei SV (April 2010). "Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in polytransfused thalassaemic patients: a meta-analysis". J. Viral Hepat. 17 (4): 236–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01170.x. PMID 19638104. S2CID 20271240.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Sanders, Mick (2011). Mosby's Paramedic Textbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 839. ISBN 9780323072755.

- ^ Ciria R, Pleguezuelo M, Khorsandi SE; et al. (May 2013). "Strategies to reduce hepatitis C virus recurrence after liver transplantation". World J Hepatol. 5 (5): 237–50. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i5.237. PMC 3664282. PMID 23717735.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Coilly A, Roche B, Samuel D (February 2013). "Current management and perspectives for HCV recurrence after liver transplantation". Liver Int. 33 Suppl 1: 56–62. doi:10.1111/liv.12062. PMID 23286847. S2CID 23601091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hepatitis C and CAM: What the Science Says. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). March 2011. (Retrieved 7 March 2011)

- ^ Liu, J.; Manheimer, E.; Tsutani, K.; Gluud, C. (March 2003). "Medicinal herbs for hepatitis C virus infection: a Cochrane hepatobiliary systematic review of randomized trials". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 98 (3): 538–44. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07298.x. PMID 12650784. S2CID 20014583.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Rambaldi, A; Jacobs, BP; Gluud, C (2007-10-17). Rambaldi, Andrea (ed.). "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (4). CD003620 (2nd rev.). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003620.pub2. PMC 8724782. PMID 17943794.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|coauthors=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fung J; Lai CL; Hung I; et al. (September 2008). "Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 6 infection: response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (6): 808–12. doi:10.1086/591252. PMID 18657036. S2CID 22715733.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y (March 2013). "Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus Infection and the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-analysis of Observational Studies". Annals of Internal Medicine. 158 (5 Pt 1): 329–37. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. PMID 23460056. S2CID 15553488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lozano, R (2012 Dec 15). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10292/13775. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first13=missing|last13=(help);|first14=missing|last14=(help);|first15=missing|last15=(help);|first16=missing|last16=(help);|first17=missing|last17=(help);|first18=missing|last18=(help);|first19=missing|last19=(help);|first20=missing|last20=(help);|first21=missing|last21=(help);|first22=missing|last22=(help);|first23=missing|last23=(help);|first24=missing|last24=(help);|first25=missing|last25=(help);|first26=missing|last26=(help);|first27=missing|last27=(help);|first28=missing|last28=(help);|first29=missing|last29=(help);|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first30=missing|last30=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Yu, Ming-Lung; Chuang, Wan-Long (March 2009). "Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West". J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24 (3): 336–45. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. PMID 19335784. S2CID 27333980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Published data for 1982-2010. "Viral Hepatitis Statistics & Surveillance". Viral Hepatitis on the CDC web site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Table 4.5. "Number and rate of deaths with hepatitis C listed as a cause of death, by demographic characteristic and year – United States, 2004-2008". Viral Hepatitis on the CDC web site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hepatitis Death Rate Creeps past AIDS". New York Times. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Blatt, L. M.; Tong, M. (2004). Colacino, J. M.; Heinz, B. A. (eds.). Hepatitis prevention and treatment. Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 32. ISBN 9783764359560.

- ^ Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F (March 2013). "The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data". J. Hepatol. 58 (3): 593–608. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005. PMID 23419824.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holmberg, Scott (12 May 2011). Brunette, Gary W.; Kozarsky, Phyllis E.; Magill, Alan J.; Shlim, David R.; Whatley, Amanda D. (eds.). CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 9780199769018.

- ^ a b Boyer, JL (2001). Liver cirrhosis and its development: proceedings of the Falk Symposium 115. Springer. pp. 344. ISBN 9780792387602.

- ^ Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (April 1989). "Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome". Science. 244 (4902): 359–62. doi:10.1126/science.2523562. PMID 2523562.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kuo G; Choo QL; Alter HJ; et al. (April 1989). "An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis". Science. 244 (4902): 362–4. doi:10.1126/science.2496467. PMID 2496467.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Winners Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research, The Lasker Foundation. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ EP patent 0318216, Houghton, M; Choo, Q-L & Kuo, G, "NANBV diagnostics", issued 1989-05-31, assigned to Chiron

- ^ Wilken, Judge. "United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit". United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Eurosurveillance editorial, team (2011-07-28). "World Hepatitis Day 2011" (PDF). Eurosurveillance. 16 (30). PMID 21813077.

- ^ a b Wong, JB (2006). "Hepatitis C: cost of illness and considerations for the economic evaluation of antiviral therapies". PharmacoEconomics. 24 (7): 661–72. doi:10.2165/00019053-200624070-00005. PMID 16802842. S2CID 6713508.

- ^ a b El Khoury, AC; Klimack, WK; Wallace, C; Razavi, H (1 December 2011). "Economic burden of hepatitis C-associated diseases in the United States". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 19 (3): 153–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01563.x. PMID 22329369. S2CID 27409621.

- ^ "Hepatitis C Prevention, Support and Research ProgramHealth Canada". Public Health Agency of Canada. Nov 2003. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Zuckerman, edited by Howard Thomas, Stanley Lemon, Arie (2008). Viral Hepatitis (3rd ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 532. ISBN 9781405143882.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ahn, Joseph; Flamm, Steven L. (August 2011). "Hepatitis C therapy: other players in the game". Clinics in Liver Disease. 15 (3): 641–56. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.008. PMID 21867942.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Vermehren, J.; Sarrazin, C. (February 2011). "New HCV therapies on the horizon". Clinical Microbiology and Infection : The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 17 (2): 122–34. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03430.x. PMID 21087349. S2CID 32983889.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Arshad M, El-Kamary SS, Jhaveri R (2011). "Hepatitis C virus infection during pregnancy and the newborn period--are they opportunities for treatment?". J Viral Hepat. 18 (4): 229–236. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01413.x. PMID 21392169. S2CID 35515919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hunt CM, Carson KL, Sharara AI (1997). "Hepatitis C in pregnancy". Obstet Gynecol. 89 (5 Pt 2): 883–890. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)81434-2. PMID 9166361. S2CID 23182340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thomas SL, Newell ML, Peckham CS, Ades AE, Hall AJ (1998). "A review of hepatitis C virus (HCV) vertical transmission: risks of transmission to infants born to mothers with and without HCV viraemia or human immunodeficiency virus infection". Int J Epidemiol. 27 (1): 108–117. doi:10.1093/ije/27.1.108. PMID 9563703.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fischler B (2007). "Hepatitis C virus infection". Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 12 (3): 168–173. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.008. PMID 17320495.

- ^ Indolfi G, Resti M (2009). "Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus infection". J Med Virol. 81 (5): 836–843. doi:10.1002/jmv.21437. PMID 19319981. S2CID 21207996.

- ^ González-Peralta RP (1997). "Hepatitis C virus infection in pediatric patients". Clin Liver Dis. 1 (3): 691–705. doi:10.1016/S1089-3261(05)70329-9. PMID 15560066.

- ^ Suskind DL, Rosenthal P (2004). "Chronic viral hepatitis". Adolesc Med Clin. 15 (1): 145–58, x–xi. doi:10.1016/j.admecli.2003.11.001. PMID 15272262.

External links[edit]

Template:Good article is only for Wikipedia:Good articles.