User:Fatalastair/sandbox

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H32O2 |

| Molar mass | 316.485 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

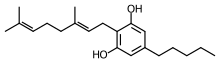

Cannabigerol (CBG) is a non-intoxicating cannabinoid found in the Cannabis genus of plants, as well as certain other plants including Helichrysum umbraculigerum.[1] CBG is the non-acidic form of cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), the parent molecule (“mother cannabinoid”) from which many other cannabinoids are made. By the time most strains of cannabis reach maturity, most of the CBG has been converted into other cannabinoids, primarily tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD), usually leaving somewhere below 1% CBG in the plant.[2]

CBG has been found to act as a high affinity α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, moderate affinity 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, and low affinity CB1 receptor antagonist.[3] It also binds to the CB2 receptor as an antagonist.[4] CBG does not trigger THC-like activity in mice, rats, gerbils and non-human primates, consistent with it being non-intoxicating.[5][6] Moreover, CBG was without effect up to 80 mg/kg in the mouse tetrad test of cannabimimetic activity (locomotor suppression, catalepsy, hypothermia and analgesia).[7]

Chemistry[edit]

It has two E/Z isomers.

Research[edit]

Pain, anxiety[edit]

CBG has been shown to have potential for alleviating pain,[8] especially neuropathic pain where tests suggest a higher efficacy than CBD.[9] CBG can also inhibit the uptake of GABA in rat brains[10], which may decrease anxiety and muscle tension with tests on mice showing that CBG induces antidepressant effects similar to imipramine.[11]

Inflammation, digestive conditions[edit]

It has been shown to improve a model of inflammatory bowel disease,[12] ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.[13]

Microorganisms[edit]

CBG has shown selective antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium intracellulare with an IC50 value of 15.0 μg/mL.[14]

Skin conditions[edit]

CBG has been shown to induce production of the body’s natural skin moisturizers, holding promise for dry-skin syndromes and with the potential to treat other skin conditions.[15]

Glaucoma[edit]

Cannabigerol has been shown to relieve intraocular pressure in studies regarding therapeutic treatment of glaucoma.[16][17]

Neuroprotection[edit]

CBG has been shown in studies with mice to have neuroprotective properties and may prove promising for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease[18] and multiple sclerosis.[19]

Antiseptic[edit]

CBG is known to have antiseptic properties[20][21] and research suggests that it might be effective against the superbug MRSA.[22]

Cancer[edit]

CBG is showing promising properties in vitro for the potential treatment of a broad range of cancers including breast, liver, lung, pancreatic, skin, ovarian, renal, bladder and colon cancer.[23][24][25][26]

Autoimmune Diseases[edit]

CBG shows potential to be a therapeutic agent for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions based on in vitro results.[28]

Legal status[edit]

United Nations[edit]

CBG is not scheduled by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

United States[edit]

CBG is not scheduled at the federal level in the United States unless it is produced from those parts of the Marijuana plant that are scheduled.

THC is the only naturally-occurring cannabinoid which is scheduled[29] in its own right at the federal level in the United States (the state scheduling laws closely follow the federal ones, with exceptions carved out in those states where medical or recreational cannabis are legal). All other naturally-occurring cannabinoids are not scheduled in their own right.

In addition, the Marijuana plant (genus Cannabis sativa L.) is scheduled[30] (although certain parts, such as the seeds and mature stalks, are excluded). Any compound or extract, to the extent that it originated from the scheduled parts of the Marijuana plant, is also scheduled[31] (including for example everyday substances such as sucrose, if derived from Marijuana). On the other hand, other than THC, all naturally-occurring cannabinoids, including CBG, are not scheduled if they were not produced from the scheduled parts of the Marijuana plant. Similarly, synthetic or biosynthesized CBG is not scheduled.

The DEA has made certain public statements that help clarify the status of cannabinoids, including:

- “if a product, such as oil from cannabis seeds, consisted solely of parts of the cannabis plant excluded from the CSA definition of marijuana, such product would not be included in the new drug code [Marijuana Extract] (7350) or in the drug code for marijuana (7360), even if it contained trace amounts of cannabinoids... Nor would such a product be included under drug code 7370 (tetrahydrocannabinols).”[32]

- “cannabinoids are controlled [only] to the extent that they are found in non-exempt parts of the cannabis plant” and “DEA is not seeking to schedule cannabinoids.”[33]

Biosynthesis[edit]

The biosynthesis of CBG begins by loading hexanoyl-CoA onto a polyketide synthase assembly protein and subsequent condensation with three molecules of malonyl-CoA.[34] This polyketide is cyclized to olivetolic acid via olivetolic acid cyclase, and then prenylated with a ten carbon isoprenoid precursor, geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), using an aromatic prenyltransferase enzyme, geranyl-pyrophosphate—olivetolic acid geranyltransferase, to biosynthesize cannabigerolic acid (CBGA), which can then be decarboxylated to yield cannabigerol.[35]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Ferdinand Bohlmann, Evelyn Hoffmann (1979). Cannabigerol-ähnliche verbindungen aus Helichrysum umbraculigerum

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola, Oier; Soydaner, Umut; Öztürk, Ekin; Schibano, Daniele; Simsir, Yilmaz; Navarro, Patricia; Etxebarria, Nestor; Usobiaga, Aresatz (2016-02-26). "Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes". Journal of Natural Products. 79 (2): 324–331. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00949. ISSN 0163-3864. PMID 26836472.

- ^ Cascio MG, Gauson LA, Stevenson LA, Ross RA, Pertwee R (December 2009). "Evidence that the plant cannabinoid cannabigerol is a highly potent alpha(2)-adrenoceptor agonist and moderately potent 5HT receptor antagonist". British Journal of Pharmacology. 159 (1): 129–141. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00515.x. PMC 2823359. PMID 20002104.

- ^ Cascio MG, Gauson LA, Stevenson LA, Ross RA, & Pertwee RG (2010). Evidence that the plant cannabinoid cannabigerol is a highly potent α2-adrenoceptor agonist and moderately potent 5HT1A receptor antagonist

- ^ Grunfeld Y, & Edery H (1969). Psychopharmacological activity of the active constituents of hashish and some related cannabinoids

- ^ Mechoulam R, Shani A, Edery H, & Grunfeld Y (1970). Chemical basis of hashish activity

- ^ El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, Ahmed S, Radwan M, Slade D, et al. (2010). Antidepressant-like effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L

- ^ Ethan B Russo (2011). Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects(p1348)

- ^ Sabatino Maione, Francesco Rossi, Geoffrey Guy, Colin Stott, Tetsuro Kikuchi (2011). Cannabinoids for use in the treatment of neuropathic pain

- ^ Banerjee, S. P.; Snyder, S. H.; Mechoulam, R. (July 1975). "Cannabinoids: influence on neurotransmitter uptake in rat brain synaptosomes". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 194 (1): 74–81. ISSN 0022-3565. PMID 168349.

- ^ Richard Musty, Richard Deyo (2006). Pharmaceutical compositions comprising cannabigerol

- ^ Borrelli, F; Fasolino, I; Romano, B; Capasso, R; Maiello, F; Coppola, D; Orlando, P; Battista, G; Pagano, E; Di Marzo, V; Izzo, AA (May 2013). "Beneficial effect of the non-psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease". Biochem Pharmacol. 85 (9): 1306–16. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.017. PMID 23415610.

- ^ Angelo Antonio Izzo, Francesca Borrelli, Stephen Wright (2011). Phytocannabinoids for use in the treatment of intestinal inflammatory diseases

- ^ Radwan, Mohamed M.; Ross, Samir A.; Slade, Desmond; Ahmed, Safwat A.; Zulfiqar, Fazila; ElSohly, Mahmoud A. (2008). "Isolation and Characterization of New Cannabis Constituents from a High Potency Variety". Planta Medica. 74 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1034311. ISSN 0032-0943. PMC 4887452. PMID 18283614.

- ^ Oláh A, Markovics A, Szabó-Papp J, Szabó PT, Stott C, Zouboulis CC, Bíró T (2016). Differential effectiveness of selected non-psychotropic phytocannabinoids on human sebocyte functions implicates their introduction in dry/seborrhoeic skin and acne treatment

- ^ Colasanti, B. (1990). "A comparison of the ocular and central effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabigerol". Journal of ocular pharmacology. 6 (4): 259–269. doi:10.1089/jop.1990.6.259. PMID 1965836.

- ^ Colasanti, B.; Craig, C.; Allara, R. (1984). "Intraocular pressure, ocular toxicity and neurotoxicity after administration of cannabinol or cannabigerol". Experimental Eye Research. 39 (3): 251–259. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(84)90013-7. PMID 6499952.

- ^ Valdeolivas, S.; Navarrete, C.; Cantarero, I.; Bellido, ML.; Muñoz, E.; Sagredo, O. (2015). "Neuroprotective properties of cannabigerol in Huntington's disease: studies in R6/2 mice and 3-nitropropionate-lesioned mice". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (1): 185–99. doi:10.1007/s13311-014-0304-z. PMC 4322067. PMID 25252936.

- ^ Granja, AG.; Carrillo-Salinas, F.; Pagani, A.; Gómez-Cañas, M.; Negri, R.; Navarrete, C.; Mecha, M.; Mestre, L.; Fiebich, BL.; Cantarero, I.; Calzado, MA.; Bellido, ML.; Fernandez-Ruiz, J.; Appendino, G.; Guaza, C.; Muñoz, E. (2012). "A cannabigerol quinone alleviates neuroinflammation in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis". J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7 (4): 1002–16. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9399-3. PMID 22971837.

- ^ Hala N. Eisohly, Carlton E. Turner, Alice M. Clark,Mahmoud A. Eisohly (1982). Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of certain cannabichromene and cannabigerol related compounds

- ^ George ANASTASSOV, Lekhram Changoer (2014). Oral care composition comprising cannabinoids

- ^ Appendino G1, Gibbons S, Giana A, Pagani A, Grassi G, Stavri M, Smith E, Rahman MM (2008). Antibacterial cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: a structure-activity study

- ^ Colin Stott, Marnie DUNCAN, Thomas Hill (2014). Active pharmaceutical ingredient (api) comprising cannabinoids for use in the treatment of cancer

- ^ Ethan B Russo (2011). Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects(p 1348)

- ^ Seung-Hwa Baek, Seok Du Han, Chan Nam Yook, Young Chae Kim, Jung Suk Kwak (1996). Synthesis and antitumor activity of cannabigerol

- ^ Seung-Hwa Baek, Seok Du Han, Chan Nam Yook, Young Chae Kim, Jung Suk Kwak (1998). Boron trifluoride etherate on silica-A modified lewis acid reagent (VII). Antitumor activity of cannabigerol against human oral epitheloid carcinoma cells

- ^ Borrelli F, Pagano E, Romano B, Panzera S, Maiello F, Coppola D, De Petrocellis L, Buono L, Orlando P, Izzo AA (2014). Colon carcinogenesis is inhibited by the TRPM8 antagonist cannabigerol, a Cannabis-derived non-psychotropic cannabinoid

- ^ Francisco J. Carrillo-Salinas, Carmen Navarrete, Miriam Mecha, Ana Feliú, Juan A. Collado, Irene Cantarero, María L. Bellido, Eduardo Muñoz, Carmen Guaza (2014) "A Cannabigerol Derivative Suppresses Immune Responses and Protects Mice from Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis". https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094733

- ^ CFR §1308.11 d(31)

- ^ CFR §1308.11 d(23)

- ^ USC > Title 21 > Chapter 13 > Subchapter I > Part A > § 802.16

- ^ DEA (2017). Clarification of the New Drug Code (7350) for Marijuana Extract.

- ^ DEA brief to US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (2017). Pages 28 and 29

- ^ Page, Jonathan; et al. (2012). "Identification of olivetolic acid cyclase from Cannabis sativa reveals a unique catalytic route to plant polyketides". PNAS. 109 (31): 12811–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200330109. PMC 3411943. PMID 22802619.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ Meinhart H,, Zenk; et al. (1998). "Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol". FEBS Letters. 427 (2): 283–285. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00450-5. PMID 9607329.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

Category:Cannabinoids Category:Terpeno-phenolic compounds Category:Resorcinols Category:CB1 receptor antagonists

What is he up to?[edit]

This is a test page for use by Alastair James[1]

Really?[edit]

Why are all these section titles questions? I don't know but this looks like it will be a really good page.Maybe it will be up to the standard of the cannabigerol page.

- ^ Radwan, Mohamed M.; Ross, Samir A.; Slade, Desmond; Ahmed, Safwat A.; Zulfiqar, Fazila; ElSohly, Mahmoud A. (2008-2). "Isolation and Characterization of New Cannabis Constituents from a High Potency Variety". Planta medica. 74 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1034311. ISSN 0032-0943. PMC 4887452. PMID 18283614.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link)