User:Etriusus/sandbox/Etriusus

2019 measles outbreaks[edit]

The 2019 measles outbreaks refer to a substantial global increase in the number of measles cases reported, relative to 2018.[1] As of April 2019, the number of measles cases reported worldwide represented a 300% increase from the number of cases seen in the previous year, constituting over 110,000 measles cases reported in the first three months of 2019.[1][2] In the first half of 2019, the World Health Organization received reports of 364,808 measles cases from 182 countries, up 182% from the same time period of 2018 when 129,239 confirmed cases were reported by 181 countries.

Countries affected[edit]

In the United States, the number of measles cases was set to reach a 25-year high by the middle of the year,[3] beginning with a large concentration of cases in the Pacific Northwest followed by another in New York,[4] as well in the U.S. state of California with two quarantines ordered at two colleges in Los Angeles on April 28, 2019.[5] Other countries reporting large increases included Brazil, Nigeria,[6] Israel,[7] Ukraine, Madagascar, India,[3] and the Philippines. However, the largest and most fatal outbreak of measles in 2019 occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[8] Other notable outbreak locations include the 2019 Kuala Koh measles outbreak, 2019 Philippines measles outbreak in Asia; the 2019 Pacific Northwest measles outbreak and 2019 New York measles outbreak in the United States; and the 2019 Philippines measles outbreak, 2019 New Zealand measles outbreak, and 2019 Samoa measles outbreak in Oceania.[citation needed]

Contributing factors[edit]

In some countries, this outbreak has been fueled by lack of access to the measles vaccine, while in others it has been exacerbated by opposition to vaccination.[1] As one such example, the outbreak in the Philippines was attributed by Health Secretary Francisco Duque III to lowered trust in the government's immunization drive due to a controversy regarding administration of a dengue vaccine.[9] The outbreak prompted President Donald Trump to shift away from his previous skepticism regarding vaccination, and to insist that parents must vaccinate their children.[10] The Trump Administration also took a forceful position of requiring vaccination, with Trump's Surgeon General Jerome Adams calling for limitations on exemptions to vaccination.[11]

.

Democratic Republic of the Congo[edit]

| 2019-2020 measles outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Measles |

| Dates | Early 2019 – 24th August 2020[12] |

| Confirmed cases | 380,766 |

Deaths | >7,018 |

In 2019, a measles epidemic broke out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The epidemic started in early 2019 in the southeast corner of the DRC and then spread to all provinces.[12][8] By June 2019 the epidemic was reported to have exceeded the death toll of the concurrent Ebola epidemic.[13] By April 2020, it had infected more than 341,000 people and claimed about 6,400 fatalities.[14] This has primarily affected children under the age of five,[8] representing 74% of infections and nearly 90% of deaths.[15]

In response, a vaccination program had been set up by the Ministry of Public Health with the aim to vaccinate more than 20 million children under the age of five.[8][13] In 2018, the measles vaccination rate was 57%.[15] The effort is supported by the Measles & Rubella Initiative, the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and GAVI, a vaccine alliance.[8][15] Also, Médecins Sans Frontières started conducting vaccination campaigns. Vaccination programs have been hampered by access to health resources, lack of resources, security issues, and mistrust.[16][8]

The measles outbreak in the DRC has been the largest and most fatal measles outbreak across the world in 2019.[8]

In April 2020 it was reported that due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccination program for measles was suspended.[17]

On 24 August 2020, the outbreak was declared over with final results of over 380,766 cases and 7,018 deaths.[18]

Philippines[edit]

| 2019 Philippines measles outbreak | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Measles |

| Index case | Indeterminate, Outbreak first declared in Metro Manila |

| Confirmed cases | 31,056 (April 13)[note 1] |

Deaths | 415 (April 13)[note 1] |

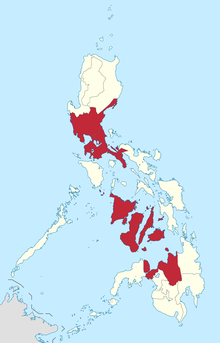

The 2019 Philippines measles outbreak began in early 2019. An outbreak of measles was officially declared in February 2019 in select administrative regions in Luzon and Visayas including Metro Manila by the Philippine government. The outbreak is attributed to lowered vaccination rates, from a high of 88% 10 to 15 years previous to 74% at the time of the outbreak, allegedly caused by the Dengvaxia controversy.

Epidemiology[edit]

The Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines declared a measles outbreak in Metro Manila due to a 550% increase of the number of patients from January 1 to February 6, 2019, compared to figures of the equivalent period from 2018.[15] Outbreaks were also officially declared in Central Luzon, Calabarzon, Western Visayas, Central Visayas.[19][20] and Northern Mindanao.[21] A joint report by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization has stated in the report that the outbreak started much earlier in late-2017 in Mindanao.[22]

Metro Manila and Calabarzon being the most affected regions with at least a thousand cases each.[23][24]

The DOH has recorded at 8,443 cases from January 1 to February 18, 2019, with 135 of these cases resulting to deaths.[25] On March 1, 2019, it was reported that there are at least 13,723 cases and 215 deaths recorded nationwide.[21]

By April 30, the DOH declared that the measles outbreak is already under control but remained hesitant in officially lifting the outbreak declaration. There are 31,056 cases and 415 deaths recorded from January 1 to April 13.[26]

Cases[edit]

In connection with the measles outbreak, the Philippine government has been maintaining a tally of confirmed cases and deaths from measles nationwide, including in regions not officially experiencing a measles outbreak.[27]

| Region | Confirmed cases |

Confirmed deaths |

Official outbreak declaration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ilocos Region (Region I) | 1,035 | 12 | No outbreak |

| Cagayan Valley (Region II) | 349 | 2 | No outbreak |

| Central Luzon (Region III) | 3,761 | 57 | Outbreak declared |

| Calabarzon | 4,838 | 98 | Outbreak declared |

| Mimaropa | 987 | 8 | No outbreak |

| Bicol Region (Region V) | 694 | 6 | No outbreak |

| Western Visayas (Region VI) | 1,371 | 5 | Outbreak declared |

| Central Visayas (Region VII) | 1,115 | 10 | Outbreak declared |

| Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) | 1,023 | 24 | No outbreak |

| Zamboanga Peninsula (Region IX) | 302 | 1 | No outbreak |

| Northern Mindanao (Region X) | 1,159 | 10 | Outbreak declared |

| Davao Region (Region XI) | 489 | 7 | No outbreak |

| Socsksargen (Region XII) | 576 | 4 | No outbreak |

| Caraga (Region XIII) | 576 | 2 | No outbreak |

| Bangsamoro (BARMM) | 451 | 4 | No outbreak |

| Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) | 367 | 1 | No outbreak |

| Metro Manila (National Capital Region; NCR) | 4,568 | 87 | Outbreak declared |

| Total (Nationwide) | 23,563 | 338 | Outbreak in 6 out 17 regions |

Cause[edit]

Vaccination against measles is available for free in government hospitals and health centers but there is a lowered trust in vaccination in the country. According to an opinion poll conducted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 2018, 32 percent of the surveyed 1,500 Filipinos trusted vaccines. In the 2015 iteration of the poll, 93 percent of the respondents said they trusted vaccines. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III attributes the lowered trust on the government's immunization drive due to the Dengvaxia controversy.[9]

The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) said that the outbreak is caused by "failure of the health system" saying that the distribution of vaccines down to the barangay level has not worked properly. They cited that immunization rates in the country have been declining in the past 10 to 15 years with about 74% immunized at the time of the outbreak compared to a high of 88%; 10 or 15 years ago.[15] UNICEF and the WHO has also attributed increase vaccine hesitancy in 2018 due to the Dengue vaccine controversy as a factor contributing to the outbreak.[22] Statistical data from UNICEF, however, shows that decline in Measles vaccination began as early as 2014, four years before the Dengvaxia controversy happened.[28]

As of March 1, 2019, 62 percent of all cases recorded at that time involved individuals who were not vaccinated against measles.[21]

Response[edit]

The Department of Health released an informercial featuring boxer Manny Pacquiao in order encourage parents and guardians to get their children vaccinated against measles in response to the outbreak.[29]

Neighbouring Malaysia's state of Sabah through the Health and People Wellbeing Ministry working towards getting all children, especially stateless people to be vaccinated following the outbreak in their neighbour the Philippines.[30]

Samoa[edit]

| 2019 Samoa measles outbreak | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Measles |

| Virus strain | D8 strain (genotype) of measles virus [31] |

| Index case | 30 September 2019 |

| Dates | 30 September 2019 – ongoing[32] |

| Confirmed cases | 5,707[33] |

Deaths | 83[34] |

| Government website | |

| http://www.samoagovt.ws/ | |

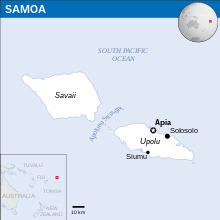

The 2019 Samoa measles outbreak began in September 2019.[35] As of 6 January 2020, there were over 5,700 cases of measles and 83 deaths, out of a Samoan population of 200,874.[34][36] Over three percent of the population were infected.[37] The cause of the outbreak was attributed to decreased vaccination rates, from 74% in 2017 to 31–34% in 2018, even though nearby islands had rates near 99%.

A state of emergency was declared on 17 November, ordering the closure of all schools, keeping children under 17 away from public events, and vaccination became mandatory. On 2 December 2019, the government imposed a curfew and cancelled all Christmas celebrations and public gatherings. Families seeking MMR vaccination were asked by the government to display an item of red cloth in front of their homes so as to alert mobile medical teams traveling the island during the lockdown.[38] Some added messages like "Help!" or "I want to live!".[39] On 5 and 6 December, the government shut down everything to bring civil servants over to the vaccination campaign. This curfew was lifted on 7 December when the government estimated that the vaccination program had reached 90% of the population. On 14 December, the state of emergency was extended to 29 December.[40] Samoan anti-vaccination activist Edwin Tamasese was arrested and charged with "incitement against a government order". Finally, as of 22 December 2019, an estimated 94% of the eligible population had been vaccinated.[37]

Background[edit]

Measles first arrived in Samoa in 1893, carried by a steamer from New Zealand. By the end of 1893, over 1,000 people (of a total population of 34,500 at that time) had died from the disease.[41]

In the early part of 2019, measles has been spreading throughout the Pacific region, with outbreaks in Tonga, Fiji, the Philippines and New Zealand.[42]

In March 2019, the WHO and UN children's agency UNICEF warned the Pacific to take proactive measures and improve immunisation rates.[43]

2019 outbreak[edit]

In August 2019, an infected passenger on one of the more than 8,000 annual flights between New Zealand and Samoa probably brought the disease from Auckland to Upolu.[38] A full outbreak began in October 2019 and continued for the next four months. As of 22 December, there were 79 deaths (0.4 per 1,000, based on a population of 200,874,[37][36] a rate of 14.3 deaths per 1000 infected) and 5,520 cases (2.75% of the population) of measles in Samoa.[32][37][36] 61 out of the first 70 deaths were aged four and under and all but seven were aged under 15.[44][13]

At least 20% of babies aged six to 11 months have contracted measles, and one in 150 babies have died.[45]

As of 20 December 94% of the population had been vaccinated.[45][46] 95% is required to acquire herd immunity for measles.[45] Measles is much more contagious compared to other infectious diseases such as polio, which only requires an 80% vaccination rate for the population to attain herd immunity.[47]

Vaccine hesitancy[edit]

The outbreak has been attributed to a sharp drop in measles vaccination from the previous year.[citation needed]

In 2013, 90% of babies in Samoa received the measles-mumps-rubella vaccination at one year of age.[39]

On 6 July 2018 on the east coast of Savai'i, two 12-month-old children died after receiving MMR vaccinations.[38] The cause of death was incorrect preparation of the vaccine by two nurses who mixed vaccine powder with expired anaesthetic instead of the appropriate diluent.[48] These two deaths were picked up by anti-vaccine groups and used to incite fear towards vaccination on social media, causing the government to suspend its measles vaccination programme for ten months, despite advice from the WHO.[49][50] The incident caused many Samoan residents to lose trust in the healthcare system.[51]

After the outbreak started, anti-vaxxers credited the deaths to poverty and poor nutrition or even to the vaccine itself, but this has been discounted by the international emergency medical support that arrived in November and December.[38] There has been no evidence of acute malnutrition, clinical vitamin A deficiency or immune deficiency as claimed by various anti-vaxxers.[38]

UNICEF and the World Health Organization estimate that the measles vaccination rate in Samoa fell from 74% in 2017 to 34% in 2018,[42][52] similar to some of the poorest countries in Africa.[39] Ideally, countries should have immunisation levels above 90%. Prior to the outbreak, vaccination rates had dropped to 31% in Samoa, compared to 99% in nearby Nauru, Niue, Cook Islands,[53] and American Samoa.[54]

Before seeking proper medical treatment, some parents first took their children to 'traditional healers' who used machines purchased from Australia that are claimed to produce immune-protective water.[39]

Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji have all declared states of emergency to tackle their 2019 measles outbreaks. The high mortality rate in Samoa is attributed to the country's low vaccination rate (31%). In Tonga and Fiji, the lack of fatalities is explained by far higher vaccination rates.[53]

Government response[edit]

Initially, schools remained open after the outbreak was declared. The Samoan government initially did not accept humanitarian support.[50]

A state of emergency was declared on 17 November, ordering the closure of all schools, keeping children under 17 away from public events, and making vaccination mandatory.[55] UNICEF has sent 110,500 vaccines to Samoa. Tonga and Fiji have also declared states of emergency.[12] Tonga closed all schools for several days, while American Samoa required all travellers from Tonga and Samoa to present proof of vaccination.[56] In Fiji, vaccines are being prioritised for young children and people travelling overseas.[57]

On 2 December 2019, the government imposed a curfew and cancelled all Christmas celebrations and public gatherings.[58][59] All unvaccinated families were ordered to display a red flag or red cloth in front of their homes to warn others and to aid mass vaccination efforts.[60] As part of aid efforts, the Royal New Zealand Air Force has transported medical supplies and equipment to Samoa. Also, New Zealand, Australian, British, French Polynesian, and French medical teams have been assisting Samoan medical authorities.[61]

On 5 and 6 December, the government shut down everything other than public utilities to assign all available civil servants to the vaccination campaign efforts.[62]

Edwin Tamasese, an anti-vaccination activist with no medical training who is also the chair of a coconut farmers’ collective,[38] was charged with "incitement against a government order".[62] He had posted online comments like “Enjoy your killing spree.”[38] He encouraged people to refuse immunisation, as he believed the vaccine caused measles,[63] and even discouraged life-saving antibiotics.[38] Tamasese faces up to two years in prison.[38]

The curfew was lifted on 7 December when the government estimated that 90% of the population had been reached by the vaccination program.[64] Parliament passed a bill on 19 December to make measles vaccinations mandatory in 2020.[65]

Nevertheless, as of 29 December, a public inquiry into the government's role in suspending vaccinations had not been announced. Deputy director of health Gaualofa Matalavea Saaga stated, "Having our case blasted out to the world is the last thing we want."[38] Samoa's political opposition called for the health minister to be removed from his position.[38]

On 31 December, Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi, the Prime Minister of Samoa, addressed the nation to ring in the New Year; the measles outbreak was a focus of his speech. He acknowledged the support of the Samoan diaspora and 49 medical teams from the following countries and organisations: Australia, China, France/French Polynesia, Fiji through UNFPA, Israel, United States/Hawaii, Japan, Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, Norway, United Nations Agencies, United Kingdom and UK Save the Children, Solomon Islands and Kiribati through the Pacific Community, American Samoa, Médecins Sans Frontières, Blacktown Doctors Medical Centre, and Samoan Doctors Worldwide.[66]

International response[edit]

The low vaccination rate of Samoa came as a surprise to New Zealand's government.[67] The Samoa Observer reported that New Zealand's Minister for Pacific People, William Sio, was" 'of the impression' that Samoa had high immunisation rates. So to learn they were in fact fatality [sic] low was a shock."[67]

Since the outbreak, several organisations and countries have responded:

- Australian Medical Assistance Teams (AUSMAT) sent a team of nurses, doctors, and public health experts as well as medical equipment and supplies to Samoa and left on 3 January 2020 after eight weeks in Samoa in one of its longest-ever missions.[68][69]

- New Zealand sent three rotations of the New Zealand Medical Assistance Team (NZMAT) of doctors, nurses and logistics specialists who supported Leulumoega Hospital and Faleolo Clinic to the west of Apia for six weeks. NZ also sent a team of nurse vaccinators, 3,000 vaccination doses and vaccine fridges to Samoa in mid-November,[70] and a small number of Intensive Care Clinicians. Residents of Rotorua, New Zealand sent two dozen infant-size coffins decorated with flowers and butterflies to Samoan families.[71] On 14 December 2019, New Zealand Foreign Minister Winston Peters announced $1 million in funds towards preventive efforts in the Pacific.[72]

- The United Kingdom EMT sent two rotations of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, an anaesthetist, and an epidemiologist for four weeks of support from the end of November to December 2019.[73]

- French Polynesia sent a team of paediatric nurses

- Israel sent Intensive Care teams to Samoa to help with relief efforts.[74]

- Hawaii sent a medical mission of 75 doctors and nurses for two days at the beginning of December to assist with the mass vaccination campaign.

- On 10 December, American Samoa declared a measles outbreak and closed public schools and park gatherings[75] and suspended all entry permits for those travelling through Samoa and Tonga to American Samoa.[76]

- UNICEF has sent 200,000 vaccines to Samoa.[12][77]

- The UN World Health Organization deployed 128 medical teams to assist in vaccination efforts. The UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) allocated $2.7 million to support the response in Samoa as well as Tonga and Fiji.[77]

- The World Bank gave a US$3.5 million grant to support the response to the outbreak and another US$9.3m grant over the next five years to improve the health system.[74]

- Israel sent a team of two paediatricians, six nurses and one physiotherapist trained in disaster medicine from the Israel Center for Disaster Medicine and Humanitarian Response.[78]

Others[edit]

As of 24 December, the following agencies had sent Emergency Medical Team personnel to assist with the outbreak:[79]

- Japan

- PACMAT

- Norway

- Save the Children

- UNFPA

- Papua New Guinea

- Samoa mo Samoa Doctors Worldwide

- French Polynesia

- Counties Manuka District Health Board

- NZMAT

- MSF

- ADRA

- Pacific Community (SPC)

- World Health Organization

Aftermath[edit]

Tuilaepa said he would propose legislation that would penalise parents who refused to vaccinate their children.[80] The Samoan government allocated US$2.5 million for relief work.[80] Immunology experts are now questioning the role of social media, primarily Facebook, and how social media facilitated the spread of vaccination hesitancy during the lethal outbreak. The Immunisation Advisory Centre in New Zealand sees the Samoan crisis as a sign that social media needs to deal with dangerous misinformation.[81] As of 25 January 2020, Tuilaepa has so far resisted calls for an inquiry.[82] Opposition MP Olo Fiti Va'ai continues to call for an inquiry and was "apologising on behalf of Parliament and telling the people of Samoa that the government had failed miserably."[83][50]

New Zealand[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | 1 August 2019 – 21 February 2020[84]

16 February – 16 May 2019[85]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casualties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The 2019–2020 New Zealand measles outbreak was an epidemic that affected New Zealand, primarily the Auckland region.[91] The outbreak was the worst epidemic in New Zealand since an influenza epidemic in 1999, and is the worst measles epidemic since 1938.[92][93]

The D8 strain was confirmed to be the main strain of the epidemic,[94][95] but the B3 strain has also been identified[96] and the epidemic has spread to several other countries. In Samoa more than 72 people have died.[31] Cases in Tonga and Fiji have also been recorded, and an outbreak in Perth began in October 2019 after a New Zealander visited while infectious.[97] In New Zealand, two unborn fetuses in second trimester have died as a result of the outbreak.[98]

Policy Response[edit]

The New Zealand Government has been criticised for its response to the epidemic, particularly due to shortages in the supply of vaccines.[99][100] Scientists have also criticised the Ministry of Health for not acting on previous recommendations to conduct national 'catch-up' campaigns with the MMR vaccine prior to the outbreak.[101]

In 2017 the New Zealand Health Ministry produced documents that showed an urgent need to increase measles immunisation among young people and that a "systematic, programmatic approach" was needed to address an immunity gap. [102] Dr Nikki Turner, Chair of the National Measles Verification Committee, met in 2018 to discuss the immunisation gap. It was noted damage was historical and immunisation rates had improved but by 2019 the gap had not been fully addressed. Many young people did not know if they had been vaccinated which indicated that poor record keeping contributed to ineffective delivery.[103] David Haymen and Turner concluded that the best way to close the immunity gap was to undertake a formal catch-up programme.[104]

Research into the 2019 epidemic traced its history and showed it was young infants who were most at risk, followed by teenagers and adults under the age of 30.[103] Analysis by the Immunisation Advisory Centre found that a generation born between 1982 and 2007 had low immunization rates, and vaccination records are incomplete for that period as the National Immunisation Register was introduced in 2005.[105] Research also suggested management strategies such as a national campaign targeting the at-risk age groups; establishment of systems to ensure adequate supplies of vaccines; provision of support for their delivery at the practice level; and creative use of community facilities to improve accessibility.[citation needed]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand, it became apparent that in the drive to obtain a vaccine for that outbreak, there was a stall in getting measles vaccination programmes rolled out effectively. Turner warned that because of this, it was possible that there would be "bigger problems with children dying from measles, and the damage from measles, than Covid."[106]

Although New Zealand has had a high demand for the MMR vaccine, resulting in a shortage, there has also been an increase in the number of people who have declined the vaccine since 2017.[77]

Cases[edit]

As of 24 February 2020, there had been 2,194 cases of measles reported throughout New Zealand since 1 January 2019.[84] Auckland had been the worst-hit region, with 1,736 cases alone.[84] The New Zealand government activated the National Health Coordination Center in August 2019 to respond to the outbreak.[107]

| Region | Cases | Hospitalised |

|---|---|---|

| Northland | 133 | 23 |

| Waitematā | 306 | 129 |

| Auckland | 274 | 108 |

| Counties Manukau | 1,157 | 435 |

| Waikato | 51 | 12 |

| Lakes | 30 | 6 |

| Bay of Plenty | 45 | 19 |

| Tairāwhiti | 0 | 0 |

| Taranaki | 8 | 3 |

| Hawke's Bay | 26 | 8 |

| Whanganui | 0 | 0 |

| MidCentral | 10 | 0 |

| Hutt Valley | 9 | 1 |

| Capital and Coast | 24 | 7 |

| Wairarapa | 1 | 0 |

| Nelson Marlborough | 1 | 0 |

| West Coast | 0 | 0 |

| Canterbury | 44 | 17 |

| South Canterbury | 2 | 0 |

| Southern | 73 | 6 |

| Total (nationwide) | 2,194 | 774 |

See also[edit]

- Taylor Winterstein, Samoan anti-vaccination campaigner

- Robert Kennedy Jr., American anti-vaccination campaigner

- Chemophobia

- Measles resurgence in the United States

- Vaccination

- Vaccine hesitancy

- 2019 in Oceania

- List of epidemics

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Fore, Henrietta H.; Ghebreyesus, Tedros Adhanom (15 April 2019). "Measles cases are up nearly 300% from last year. This is a global crisis". CNN.

- ^ Aug 12, Stephanie Soucheray | News Reporter | CIDRAP News |; 2019. "Global measles outbreaks make 2019 a record-setting year". CIDRAP. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cohen, Elizabeth (15 April 2019). "Measles reaches 2nd-highest level in U.S. in 25 years". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Scutti, Susan (30 January 2019). "Measles outbreaks in Washington and New York challenge public health systems". CNN.

- ^ Drash, Wayne (28 April 2019). "Measles quarantine issued at two California universities". CNN.

- ^ "Global Measles Outbreaks". www.cdc.gov. 9 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Measles - NYC Health". www1.nyc.gov.

- ^ a b c d e f g Catesby Holmes (19 October 2019). "Outbreaks of measles: compounding challenges in the DRC". The Conversation. Retrieved 22 November 2019. Cite error: The named reference "holmes" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Measles outbreak declared in 3 more regions". ABS-CBN News. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019. Cite error: The named reference "declares3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Vazquez, Maegan (26 April 2019). "Trump now says parents must vaccinate children in face of measles outbreak". CNN.

- ^ "US Surgeon General visits Washington as measles outbreak spreads". KING. 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d "DR Congo measles: Nearly 5,000 dead in major outbreak". BBC. 21 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

Close to a quarter of a million people have been infected this year alone. The World Health Organization (WHO) says this is the world's largest and fastest-moving epidemic.

- ^ a b c "Congo declares measles epidemic after it kills more than Ebola". Reuters. 20 June 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Murray, Lisa (7 April 2020). "Measles: In Ebola's shadow, a quiet killer is on a rampage in DRC - Al Jazeera". Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

Since the start of 2019, measles epidemic has infected more than 341,000 people and killed some 6,400 in the DRC.

- ^ a b c d e "As measles deaths in the Democratic Republic of the Congo top 4,000, UNICEF rushes medical kits to health centers and vaccinates thousands more children". UNICEF. 9 October 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019. Cite error: The named reference "unicef" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "DRC struggles to contain measles outbreak". AlJazeera. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "117 Millionen Kindern droht Ansteckung mit Masern". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "DRC: More Ebola and plague cases reported, End of measles epidemic declared". 29 August 2020.

- ^ "DOH Expands Measles Outbreak Declarations to Other Regions". Department of Health. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Questions and answers on the measles outbreak in the Philippines". World Health Organization. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 07 re Measles Outbreak, 01 March 2019, 5:00 PM". reliefweb. National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. 1 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Philippines Situation Report 11 Measles Outbreak" (PDF). UNICEF, World Health Organization. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Cruz, Sofia Toma (11 February 2019). "At least 70 deaths due to measles – DOH". Rappler. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Number of measles cases climbs to more than 4,300 — DOH". CNN Philippines. 11 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Measles cases breach 8,000 mark but may dwindle in April – DOH". CNN Philippines. 19 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Measles outbreak 'almost over': DOH". Philippine News Agency. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b "NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 13 re Measles Outbreak, 26 March 2019, 5:00 PM" (PDF). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Philippines: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2018 revision data.unicef.org accessed 15 May 2020

- ^ Crisostomo, Sheila (19 February 2019). "Measles outbreak death toll hits 136". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Stephanie Lee (14 February 2019). "Sabah moves to control measles after Philippines outbreak". The Star. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

strainwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Samoa, Fiji and Tonga - Measles outbreak (DG ECHO, WHO, UNICEF and media) (ECHO Daily Flash of 25 November 2019) - Samoa". ReliefWeb. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 25 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jan25was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Two more deaths from measles in samoa over new year period". Radio New Zealand. 7 January 2020. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Ministry of Health Press Release 1 - Measles Epidemic - Samoa". ReliefWeb. Government of Samoa. 16 November 2019. Archived from the original on 1 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "Population & Demography Indicator Summary". Samoa Bureau of Statistics. 22 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Government of Samoa (22 December 2019). "National Emergency Operation Centre, update on the measles outbreak: (press release 36) 22 December, 2019". @samoagovt. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Deer, Brian (20 December 2019). "Samoa's perfect storm: How a collapse in vaccination rates killed more than 70 children". The Telegraph. London, UK. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Kwai, Isabella (19 December 2019). "'Why My Baby?' How Measles Robbed Samoa of Its Young". The New York Times. US. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa measles state of emergency extended". Radio New Zealand. 14 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019.

- ^ Davies, Samuel H. (1894). "Epidemic Measles at Samoa". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1742): 1077. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1742.1077. PMC 2404975. PMID 20754822.

- ^ a b Whyte, Chelsea (6 December 2019). "Samoan government takes drastic measures to fight measles outbreak". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Duckor-Jones, Avi (5 February 2020). "Tragedy in paradise: How Samoa is faring after the measles epidemic". The Listener. NZ: Bauer Media Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020.

- ^ Government of Samoa (9 December 2019). "National Emergency Operation Centre, update on the measles outbreak: (press release 23) 9 December". @samoagovt. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Gibney, Katherine (12 December 2019). "Measles in Samoa: how a small island nation found itself in the grips of an outbreak disaster". The Conversation. Melbourne, Australia: The Conversation Media Trust. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019.

- ^ Kerr, Florence (20 December 2019). "Samoa measles outbreak: Death toll continues to rise, 39 new cases". stuff.co.nz. NZ: Stuff Ltd. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019.

- ^ Belluz, Julia (18 December 2019). "Tiny Samoa has had nearly 5,000 measles cases. Here's how it got so bad". Vox. US: Vox Media LLC. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020.

- ^ Pacific Beat (2 August 2019). "Samoan nurses jailed over deaths of two babies who were given incorrectly mixed vaccines". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corp. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (28 November 2019). "Samoa measles outbreak: WHO blames anti-vaccine scare as death toll hits 39". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Lagipoiva Cherelle; Lyons, Kate (17 December 2019). "'These babies should not have died': How the measles outbreak took hold in Samoa". The Guardian. UK. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019.

- ^ Clarke, Melissa (8 December 2019). "Anatomy of an epidemic: How measles took hold of Samoa". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corp. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2018 revision" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b "The wrong jab that helped cause a measles crisis". BBC News. UK. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019.

- ^ "American Samoa declares measles outbreak". SBS News. Australia. 8 December 2019. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa declares state of emergency over deadly measles outbreak". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corp. 17 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019.

- ^ Wibawa, Tasha (19 November 2019). "'Deaths keep climbing': How did a measles outbreak become deadly in Samoa?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Children stay home, Christmas gatherings cancelled in Samoa". Radio New Zealand. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Samoa measles outbreak: Police urge public to keep to curfew". Radio New Zealand. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019.

- ^ Silk, John; AFP (4 December 2019). "Samoan measles epidemic: Unvaccinated advised to display red flags in front of their homes". Deutsche Welle. Germany. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019.

- ^ "NZDF supporting Samoa measles epidemic response". Radio New Zealand. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Merrit (6 December 2019). "Samoa Arrests Anti-Vaccination Activist As Measles Death Toll Rises". NPR. US. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020.

- ^ Purtill, James (5 December 2019). "Samoan measles anti-vaxxer with links to Australia arrested after spreading conspiracy theories". triple j - Hack. Australian Broadcasting Corp. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa measles vaccination hits target but new cases still rising". Al Jazeera English. 7 December 2019. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa's measles death toll rises to 78". Radio New Zealand. 20 December 2019. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019.

- ^ Feagaimaali'i, Joyetter (1 January 2020). "Prime Minister addresses nation at start of 2020". Samoa Observer. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020.

- ^ a b Mayron, Sapeer (5 January 2020). "It's okay to vaccinate, Minister Aupito spreads the message". Samoa Observer. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Statement on Samoa measles outbreak". ReliefWeb. Government of Australia. 21 November 2019. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Soli (5 January 2020). "Australia's emergency measles mission ends". Samoa Observer. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Measles outbreak: Samoa declares state of emergency after 6 fatalities". Deutsche Welle. Germany. 18 November 2019. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019.

- ^ Gerson, Michael (10 December 2019). "Samoa has become a case study for 'anti-vax' success". Washington Post. US. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa measles outbreak: New Zealand gives $1m for preventive action in Pacific". Stuff. New Zealand: Stuff Limited. 14 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019.

- ^ Department for International Development (29 November 2019). "UK medics fight deadly measles outbreak in Samoa - Press release". UK Government. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b Meyer, Jenny; RNZ (10 December 2019). "Jabs could knock out kid-killing measles epidemic in Samoa". New Zealand Herald. NZME. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019.

- ^ Hofschneider, Anita (9 December 2019). "Hawaii Lt Gov Says Samoa Medical Mission Won't Be The Last". Honolulu Civil Beat. HI, US. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019.

- ^ "American Samoa tightens entry as measles fears grow". Radio New Zealand. 10 December 2019. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "UN team aids Samoa response to deadly measles epidemic". UN News. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2021. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Leichman, Abigail Klein (8 December 2019). "Israeli medical experts fly to help Samoan measles victims". Israel21c news. San Francisco, US. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020.

- ^ Govt Press Release (25 December 2019). "Emergency Medical Teams Work Through Christmas". Samoa Global News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Samoa govt allocates more funds for measles epidemic". Radio New Zealand. 30 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019.

- ^ Hendrie, Doug (11 December 2019). "Facebook challenged over spread of anti-vaccine content in measles-stricken Samoa". newsGP. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019.

- ^ "Samoa's measles crisis wanes, but questions remain unanswered". Radio New Zealand. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ "MP calls for inquiry into Samoa's measles epidemic". Radio New Zealand. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Measles weekly report" (PDF). Public Health Surveillance. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Canterbury measles outbreak declared officially over". TVNZ. Retrieved 4 March 2021 – via TVNZ.

- ^ "Measles weekly report" (PDF). Public Health Surveillance. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Three cases of Measles in Australia". 9 news. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "2019 measles outbreak WA Information". WA Health. 18 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Measles outbreak hits Queensland". 7 news. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Measles Outbreak declared in Fiji". fijisun. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "2019 measles outbreak information". Ministry of Health NZ. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "A timeline of epidemics in New Zealand" (PDF).

- ^ "Vaccines mean opening our borders to Covid". 9 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Iannelli, Vincent; MD (13 May 2017). "Measles Vaccines vs Measles Strains". Vaxopedia. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "National Measles Response and Recovery Appeal, 6 December 2019 - Samoa". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "2019 Canterbury Measles Outbreak – A summary of cases" (PDF). New Zealand Community and Public Health. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bell, Frances (2 October 2019). "Fears over growing and 'unprecedented' Perth measles outbreak linked to much bigger NZ one". ABC News. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Amid Auckland's measles outbreak, two second-trimester unborn babies die". TVNZ. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Katie. "Simon Bridges hits out at Government over measles outbreak handling". Newshub. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Laird, Lindy (20 September 2019). "47 measles cases in North, MP says not enough action". Northern Advocate. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Hancock, Farah. "'Shameful' measles outbreak predicted". Stuff. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "Measles outbreak: Call for national approach". www.scoop.co.nz. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b "A measles epidemic in New Zealand: Why did this occur and how can we prevent it occurring again?". www.nzma.org.nz. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Joining the dots: What's really causing New Zealand's measles epidemics". RNZ. 25 May 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Newton, Kate (25 May 2019). "Joining the dots: What's really causing New Zealand's measles epidemics". RNZ. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Nikki Turner: Let's keep our eyes on the ball - The University of Auckland". www.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Small, Zane; Lynch, Jenna. "'This is serious': National Health Coordination Centre activated over measles outbreak". Newshub.

Category:Disease outbreaks in the Philippines measles outbreak Philippines