User:Epipelagic/sandbox/sources

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Epipelagic/sandbox/sources. |

RESOURCES AND WORKING DRAFTS ONLY

Viruses and nanbots[edit]

- molecular robotics

From: Virome:

Viromes were the first examples of shotgun community sequence,[1] which is now known as metagenomics. In the 2000s, the Rohwer lab sequenced viromes from seawater,[1][2] marine sediments,[3] adult human stool,[4] ...

T. Hinckley et al. Development of phage-based nanobots for the recognition, separation and detection of bacterial pathogens. 255th American Chemical Society National Meeting, New Orleans, March 20, 2018.

J. Chen et al. Lyophilized engineered phages for Escherichia coli detection in food matrices. ACS Sensors. Vol. 2. October 2017, p. 1573. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.7b00561

J. Chen et al. Bacteriophage-based nanoprobes for rapid bacteria separation. Nanoscale. Vol. 7. August 2015, p. 16230. doi: 10.1039/c5nr03779d

Breitbart, M; Felts, B; Kelley, S; Mahaffy, JM; Nulton, J; Salamon, P; Rohwer, F (22 March 2004). "Diversity and population structure of a near-shore marine-sediment viral community". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1539): 565–74. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2628. PMC 1691639. PMID 15156913.

Rohwer, F. and Thurber, R.V., 2009. "Viruses manipulate the marine environment". Nature, 459(7244), p. 207.

Brussaard, C.P., Wilhelm, S.W., Thingstad, F., Weinbauer, M.G., Bratbak, G., Heldal, M., Kimmance, S.A., Middelboe, M., Nagasaki, K., Paul, J.H. and Schroeder, D.C., 2008. Global-scale processes with a nanoscale drive: the role of marine viruses". The ISME Journal, 2(6), p. 575.

Brum, J.R., Ignacio-Espinoza, J.C., Roux, S., Doulcier, G., Acinas, S.G., Alberti, A., Chaffron, S., Cruaud, C., De Vargas, C., Gasol, J.M. and Gorsky, G., 2015. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science, 348(6237), p. 1261498. [1] • "Ocean microbes produce half of the oxygen we breathe (1) and drive much of the substrate and redox transformations that fuel Earth’s ecosystems (2). However, they do so in a constantly evolving network of chemical, physical and biotic constraints – interactions which are only beginning to be explored. Marine viruses are presumably key players in these interactions (3, 4) as they affect microbial populations through lysis, reprogramming of host metabolism, and horizontal gene transfer"

Brum, J.R. and Sullivan, M.B., 2015. Rising to the challenge: accelerated pace of discovery transforms marine virology. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13(3), p. 147.[2] • "Marine viruses have important roles in microbial mortality, gene transfer, metabolic reprogramming and biogeochemical cycling" • "Viruses were once thought to have a limited influence in marine environments because initial studies detected few viruses capable of infecting cultivated bacteria1. However, similar to early studies of marine bacteria2 cultivation grossly underestimated marine viral abundance. In 1989, direct microscopic examination of seawater showed an ocean teeming with millions of viruses per milliliter of seawater1. Almost simultaneously, another study showed that viruses actively infect marine microorganisms3, which drive energy and nutrient transformations that fuel life on our planet4, leading to speculation that viruses have a major influence on marine ecosystem dynamics1,3 23 ." • "In summary, an explosion of novel tools, technologies and theories are transforming our conceptual view of marine viral ecology. Given this, and the experimental advantages of studying microbial systems, we further challenge the field to advance our understanding of ecological interactions of micro- and nano-scale entities to match, and perhaps even surpass, that of their macro-scale counterparts. " • "" • "" • "" ETC

Breitbart M (2012) Marine viruses: truth or dare. Ann Rev Mar Sci 4: 425–448.

Hemminga, M.A., Vos, W.L., Nazarov, P.V., Koehorst, R.B., Wolfs, C.J., Spruijt, R.B. and Stopar, D. (2010) "Viruses: incredible nanomachines. New advances with filamentous phages" European Biophysics Journal, 39(4): 541–550. doi:10.1007/s00249-009-0523-0 • "From the perspective of nanotechnology, viruses can be regarded as efficient nanomachines, producing numerous copies of themselves."

Johnson, J.E. (2010) "Virus particle maturation: insights into elegantly programmed nanomachines". Current opinion in structural biology, 20(2): 210–216. • "Capsid maturation is an accessible natural example of a nano machine"

Koudelka, K.J., Pitek, A.S., Manchester, M. and Steinmetz, N.F. (2015) "Virus-based nanoparticles as versatile nanomachines". Annual review of virology, 2: 379–401. • "Nanoscale engineering is revolutionizing the way we prevent, detect, and treat diseases. Viruses have played a special role in these developments because they can function as prefabricated nanoscaffolds that have unique properties and are easily modified. The interiors of virus particles can encapsulate and protect sensitive compounds, while the exteriors can be altered to display large and small molecules in precisely defined arrays. These properties of viruses, along with their innate biocompatibility, have led to their development as actively targeted drug delivery systems that expand on and improve current pharmaceutical options." • "In contrast, bionanomaterials based on viruses allow for the templated assembly of millions of identical nanoparticles and their production in living cells. Viruses are ubiquitous in the environment, and those that infect bacteria, mammals, or plants have all been used to manufacture virus-based nanoparticles (VNPs). Viruses are an ideal starting point because they have evolved naturally to deliver nucleic acids and can therefore be subverted for the delivery of other molecules, such as drugs and imaging reagents. Finally, viruses replicate prodigiously, allowing the inexpensive manufacture of VNPs on an industrial scale." • "VNPs are high-precision materials that self-assemble into symmetrical and polyvalent structures that can be tailored at the atomic level. Virus-based materials come in a variety of shapes and sizes, but most are monodisperse with geometries that can be custom modified... Whereas some synthetic nanoparticles persist in the body for weeks or even longer (168–171), virus-based materials are subject to proteolytic degradation and thus are removed safely from the body within days"

Krupovic, M., Prangishvili, D., Hendrix, R.W. and Bamford, D.H. (2011) "Genomics of bacterial and archaeal viruses: dynamics within the prokaryotic virosphere". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 75(4): 610–635. • "Over the past few years, the viruses of prokaryotes have been transformed in the view of microbiologists from simply being convenient experimental model systems into being a major component of the biosphere. They are the global champions of diversity, they constitute a majority of organisms on the planet, they have large roles in the planet’s ecosystems, they exert a significant—some would say dominant—force on the evolution of their bacterial and archaeal hosts, and they have been doing this for billions of years, possibly for as long as there have been cells."

Sunagawa, S., Coelho, L.P., Chaffron, S., Kultima, J.R., Labadie, K., Salazar, G., Djahanschiri, B., Zeller, G., Mende, D.R., Alberti, A. and Cornejo-Castillo, F.M., 2015. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science, 348(6237), p. 1261359. [3] • "We identify ocean microbial core functionality and reveal, given the physicochemical differences, a surprisingly high fraction of its abundance (>73%) to be shared with the human gut microbiome." • "Microorganisms are ubiquitous in the ocean environment, where they play key roles in biogeochemical processes, such as carbon and nutrient cycling (1). With an estimated 104 - 106 cells per milliliter, their biomass combined with high turnover rates and environmental complexity, provides the grounds for immense genetic diversity (2). These microorganisms, and the communities they form, drive and respond to changes in the environment, including climate change-associated shifts in temperature, carbon chemistry, nutrient and oxygen content, and alterations in ocean stratification and currents (3)."

Paez-Espino, D., Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A., Pavlopoulos, G.A., Thomas, A.D., Huntemann, M., Mikhailova, N., Rubin, E., Ivanova, N.N. and Kyrpides, N.C., 2016. Uncovering Earth’s virome. Nature, 536(7617), p. 425. [4] • "Viruses are the most abundant entities across all habitats, and a major reservoir of genetic diversity1 affecting biogeochemical cycles and ecosystem dynamics1. Exploration of viral populations in oceans of the world and within the human microbiome has illuminated considerable genetic complexity2,3"

Viruses as nanomachines

from: http://www.storagetwo.com/blog/2016/2/viruses-nanorobots-among-us Viruses defy the usual categories we use to define life. They don’t have cells. They don’t consume, store, or use energy. They don’t move. They don’t reproduce without a host. They don’t show any signs of activity at all unless they’re in an environment where they can spread. They have been compared to nanorobots, and in many ways, it is an apt description. If viruses are not “alive” as we define it, then what should we call these strange evolving and replicating entities?

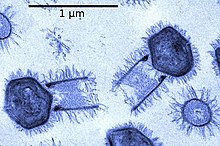

Some phages "look just like lunar landers sent from alien spaceships", or as though they have been constructed by a child using an erector set. - Thinking Like a Phage: The Genius of the Viruses That Infect Bacteria and Archaea"Thinking Like a Phage", by Merry Youle.

Doubtful marine viruses could infect humans since viruses need to be sensitively tuned to the target host, which in this case is not present in the ocean

From Virus: Viruses display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, called morphologies. In general, viruses are much smaller than bacteria. Most viruses that have been studied have a diameter between 20 and 300 nanometres. Some filoviruses have a total length of up to 1400 nm; their diameters are only about 80 nm.[5] Most viruses cannot be seen with an optical microscope so scanning and transmission electron microscopes are used to visualise them.[6]

From Virus: Viruses are by far the most abundant biological entities on Earth and they outnumber all the others put together.[7] They infect all types of cellular life including animals, plants, bacteria and fungi.[8] Different types of viruses can infect only a limited range of hosts and many are species-specific. Some, such as smallpox virus for example, can infect only one species—in this case humans,[9] and are said to have a narrow host range. Other viruses, such as rabies virus, can infect different species of mammals and are said to have a broad range.[10] The viruses that infect plants are harmless to animals, and most viruses that infect other animals are harmless to humans.[11]

"The marine environment is primarily occupied by microbes, mainly bacteria and protists, which account for about 70% of the total marine biomass."

- earth's total biomass is 560 billion tonnes.

- Cyanophage

- Microbial ecology

Middelboe, M. and Brussaard, C. (2017) "Marine viruses: key players in marine ecosystems". Viruses. 9(10): 302. doi:10.3390/v9100302

- virophages

Paez-Espino, D., Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A., Pavlopoulos, G.A., Thomas, A.D., Huntemann, M., Mikhailova, N., Rubin, E., Ivanova, N.N. and Kyrpides, N.C. (2016) "Uncovering Earth’s virome". Nature, 536(7617): 425. doi:10.1038/nature19094 [5]

- ^ a b Breitbart, M; Salamon, P; Andresen, B; Mahaffy, JM; Segall, AM; Mead, D; Azam, F; Rohwer, F (29 October 2002). "Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (22): 14250–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914250B. doi:10.1073/pnas.202488399. PMC 137870. PMID 12384570.

- ^ Angly, FE; Felts, B; Breitbart, M; Salamon, P; Edwards, RA; Carlson, C; Chan, AM; Haynes, M; Kelley, S; Liu, H; Mahaffy, JM; Mueller, JE; Nulton, J; Olson, R; Parsons, R; Rayhawk, S; Suttle, CA; Rohwer, F (November 2006). "The marine viromes of four oceanic regions". PLOS Biology. 4 (11): e368. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040368. PMC 1634881. PMID 17090214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Breitbart, M; Felts, B; Kelley, S; Mahaffy, JM; Nulton, J; Salamon, P; Rohwer, F (22 March 2004). "Diversity and population structure of a near-shore marine-sediment viral community". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1539): 565–74. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2628. PMC 1691639. PMID 15156913.

- ^ Breitbart, M; Hewson, I; Felts, B; Mahaffy, JM; Nulton, J; Salamon, P; Rohwer, F (October 2003). "Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces". Journal of Bacteriology. 185 (20): 6220–3. doi:10.1128/jb.185.20.6220-6223.2003. PMC 225035. PMID 14526037.

- ^ Collier pp. 33–55

- ^ Collier pp. 33–37

- ^ Crawford, Dorothy H.. Viruses: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, US; 2011. ISBN 0-19-957485-5. p. 16.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Dimmock p. 49was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Shors p. 388

- ^ Shors p. 353

- ^ Dimmock p. 272

- ^ Wilhelm, S., Bird, J., Bonifer, K., Calfee, B., Chen, T., Coy, S., Gainer, P., Gann, E., Heatherly, H., Lee, J. and Liang, X. (2017) "Review: A student’s guide to giant viruses infecting small eukaryotes: From Acanthamoeba to Zooxanthellae". Viruses, 9(3): 46. doi:10.3390/v9030046

Freshwater fish of New Zealand[edit]

"Native freshwater fishes of New Zealand. The fauna is sparse (~ 40 species) and characterised by a high degree of diadromy... this fauna offered an opportunity to 'explore pattern and process, cause and effect, evolution and biogeography,in a way that would have been much more difficult in areas with more speciose faunas'... The family Galaxiidae comprises a group of southern hemisphere fishes whose wide geographic range and the diversity of habitats they have colonised are somewhat akin to the northern hemisphere salmonids... studying the ecology of the migrations of juvenile galaxiids (known locally as 'whitebait', and considered a delicacy)"[6]

"At present, 50 genetically distinct, extant fish species are recognised in freshwaters in New Zealand with another three or four species yet to be formally named (Allibone et al. 2010) (Table 1). However, the actual species number is hard to define because eight are classified as ‘freshwater indeterminate’: they are essentially marine species but move far into fresh waters for long periods. Only one native fish, the endemic grayling (Prototroctes oxyrhynchus), is known to have become extinct since the first human settlement of New Zealand c. 700 years ago, although many other species have become locally extinct over much of their pre-European range. New Zealand’s freshwater fish fauna is unique, with 92% of the named species found nowhere else in the world."[7]

"Diadromy: One feature of the New Zealand freshwater fish fauna is the large proportion of diadromous species: namely, fish that undertake two migratory movements between the ocean and fresh water in their life cycles. Diadromous fish employ three very distinctly different strategies: anadromy, catadromy, and amphidromy (Table 3). Anadromous fish spend their adult life in the sea, move to fresh water to breed, then die; catadromy is essentially the opposite, with fish spending most of their adult life in fresh water before a final migration to the ocean to breed and die; and amphidromy is an intermediate strategy in which adults live in fresh water, usually breed yearly, and the juveniles spend time in the ocean before returning to fresh water (McDowall 1988). A few decades ago diadromy was thought to be obligatory in most diadromous species, but we now know that in some species diadromy seems to be facultative, as not all individuals migrate. In the currently recognised extant taxa, diadromy is thought to be obligatory in 13 species and facultative in 6, and at least one diadromous species is present in each of the nine families in the New Zealand fauna (Ling 2010). Seven diadromous species include landlocked populations, usually, but not always, are formed when a lake outlet is blocked (Closs et al. 2003)"[8]

Overview[edit]

"Compared to other countries, New Zealand has a sparse freshwater fish fauna of just over fifty species. But it is unique and comprises at least thirty-five native species of which thirty-one are found only in New Zealand. Most of the native species belong to just four families of fish, and include twenty galaxiids, seven bullies, two eels, and two smelts. Nine potentially new galaxiid species have been recently found in Otago but are yet to be named so the list is not yet complete."[2]

"Because of the sparse native fish fauna, a large number of species have been introduced (legally, illegally and accidently). Of the fifteen species that are known to have established breeding populations in more than one location, six are salmonids (Salmonidae), four are cyprinids (cyprinidae), and three are live-bearers (Poecillidae). The redfin perch and the bullhead catfish are also well established. A further two species (grass and silver carp) are present, but do not breed. Five other species have very restricted populations and their current status is uncertain."[2]

"An unusually high proportion of the native fish are diadromous (i.e. they all have a marine phase in their lifecycle). Although several grow to adulthood in freshwater then migrate downriver to breed in the sea (e.g., eels, mullet, freshwater flounder), most breed in freshwater with their juveniles travelling downriver to develop at sea (e.g., galaxiids, smelt and bullies). Only the lamprey breeds and develops in freshwater streams and spends its entire adult life at sea."[2]

"Because these diadromous species all need to migrate upriver from the sea at some stage, they are vulnerable to barriers created by falls, chutes, dams, weirs, and culverts. They also vary widely in their ability to move upriver. Some species (eels and certain galaxiids) can climb vertical wet rock faces and they penetrate far upriver to high altitudes. Others cannot climb and are restricted to lowland, coastal streams. As a consequence, the geographical distributions of the species vary widely within rivers and are greatly affected by both altitude and distance from the sea."[2]

"Many of the native species are small, cryptic and/or are nocturnal so it is not surprising that most people are not aware that they are present. They express surprise when they learn that there is more to the native fauna than just eels and galaxiids. For example, redfin bullies are brightly coloured and good in aquaria, whereas torrent fish are shaped like a stealth fighter and are well adapted to cope with the high water velocities found in rapids where they live."[2]

"Many of the largest native galaxiids (called kokopu) live mostly in small streams running beneath forest or bush canopies. Widespread conversion of forest to pasture has resulted in their decline, and the introduction of predatory trout restricts their distributions within forested streams. As a consequence of these changes, together with the creation of migration barriers and loss of habitats, a number of the native fish are now endangered. A 2010 report indicated that whereas only the grayling is extinct, eight species are nationally threatened and another twelve are now in decline."[2]

"Eels and galaxiids are responsible for commercial and cultural fisheries in New Zealand rivers with five species of galaxiids comprising the national delicacy known as 'whitebait'. Sports fisheries are based on introduced species, including chinook salmon (South Island rivers), rainbow and brown trout (lakes and rivers nationally), and coarse fish (perch, rudd, tench, koi carp), mainly in small North Island lakes. Other introduced species (i.e., gambusia, catfish, goldfish) have few if any values and some of the introduced species are pests in some places because they either reduce native biodiversity, degrade other species habitats, or contribute to the decline of water quality in lakes."[2]

Native species[edit]

"The latest information indicates that New Zealand has around 40 native species of freshwater fish. This count may increase as new genetic techniques bring a better understanding of the diversity within some fish groups. Thirty-three species are known only in New Zealand. Kōaro, longfin eels and spotted eels are also found in Australia, while lamprey and īnanga also occur in Australia, Chile and Argentina. New Zealand’s native freshwater fish belong to eight distinct families: the jawless lamprey, eels, smelts, southern graylings, galaxiids, torrentfish, bullies and flounder. Most are relatively small, although the eels are an obvious exception – some female longfin eels are up to 2 metres long and 25 kilograms in weight."[3]

Age[edit]

"Longfin eels are the longest-living native fish, generally taking 20–30 years to reach maturity. Some large female eels stay in fresh water for over 80 years. In contrast, smaller species, such as īnanga, reach maturity in just one year and rarely live longer than three years."[3]

Diet[edit]

"Almost all native fish prey on invertebrates or other fish. However, historical accounts indicate that the now-extinct grayling (Prototroctes oxyrhynchus) was an exception and grazed on algae from river rocks."[3]

Migration and life cycles[edit]

"Nearly half the native fish species migrate to and from the sea during their life cycle. As not all species can climb rapids and waterfalls, freshwater fish are most diverse at low altitudes, closer to the coast.

- Lampreys reproduce in fresh water but develop mostly at sea.

- Eels reproduce at sea, but most of their growth occurs in fresh waters.

- The five species of galaxiids that form the whitebait catch lay their eggs in fresh water, but their larvae quickly migrate to sea and spend a few months there before heading back to fresh water."[3]

Distribution[edit]

"Although not found elsewhere, many of New Zealand’s freshwater fish do have close relatives in Australia, South America and Southern Africa. Two species that do exist beyond New Zealand are lampreys and īnanga. This distribution, with other evidence, indicates that migration across the oceans is an important factor explaining the global spread of these fish."[3]

Factors affecting life in fresh water[edit]

"A range of factors influence the types of species that live in different parts of New Zealand.

- At a broad level, evolutionary history and climate determine which species are found in certain regions.

- At a finer level, factors such as water quality, land use, channel shape, or lake type influence the range of species found in a river reach or lake.

- Small-scale factors (light and food availability, cover, predation, competition, water depth and speed) also control which species live at certain sites within a river or lake. All these factors can interact to shape freshwater ecosystems."[4]

Light availability[edit]

"Without light, plants cannot grow. There are big differences between the communities living in the well-lit surface and edges of lakes, and those in the depths, which receive little or no light. Turbid (muddy) water also restricts the amount of light that reaches the bed. Lakes with large shallow areas tend to be more productive than lakes with little shallow water (because more light reaches the lake bed). A similar situation exists in river systems, where heavily shaded streams rely on leaves and other organic material from the surrounding catchment to fuel the ecosystem. In larger rivers the canopy opens up, allowing algal production to become more important."[4]

Predators versus available food[edit]

"There is debate about whether the number of invertebrates (insects and other animals without backbones) in a habitat is controlled by the number of predators that will eat them, or by the amount of food available for them. Both factors are important, but their relative importance may vary. For example, the introduction of trout appears to have changed some streams from systems controlled by the available food to those controlled by trout as predators."[4]

Disturbances: floods and droughts[edit]

"Rivers and streams are particularly prone to disturbance, due to huge changes in flows, as in floods and droughts. Although these are often seen as harmful, it appears that a moderate level of disturbance can promote higher diversity in some systems. This makes sense: if there is some variation in an environment, more life forms may be able to live there."[4]

Human impact[edit]

"Irrigation and hydroelectricity projects. Water is currently in high demand, and the value of freshwater systems is often weighed against the potential value of using the water. Hydroelectric dams and large irrigation projects can turn running waters into lakes, affect water quality, and restrict fish movement along river systems."[4]

Farming[edit]

"Many rivers and lakes now have high concentrations of nutrients, sediment and faecal bacteria, and problems with algal blooms (a heavy growth of algae). This is because more intense farming leads to excessive runoff of sediment and fertilisers into waterways. Taking water for irrigation has also harmed the water quality of lowland streams and some lakes. The Rotorua lakes are classic examples. Too many nutrients enter the lakes, causing algal blooms, which in turn starve the water of oxygen. At times, the lakes are closed for swimming, due to low water quality."[4]

Pests[edit]

"Various pests have become established in freshwater systems. Pest fish prey on native species and can stir up mud and alter the water quality. Invasive aquatic plants grow profusely, changing the habitat and causing problems for recreational activities. For example the introduced weed Lagarosiphon major can grow so profusely that it clogs the shoreline, making it unattractive for swimming. Even tiny algae can cause problems. In 2004 outbreaks of Didymosphenia geminata smothered South Island riverbeds, affecting everything living there."[4]

Where are the fish?[edit]

"New Zealand has an abundance of cool clear rivers, streams and lakes, but if you look into the water you will not usually see many fish. The journals of many early settlers refer to empty rivers. Believing there were no native fish, they introduced trout and salmon – species that would meet their expectations as game and a source of food. But it was a mistake to think the rivers were empty, as Māori had long caught a wide variety of native fish. European settlers soon discovered the delight of fresh whitebait, and learned to fish for upokororo (grayling). As Māori knew well, eels were a nutritious addition, and livened up an often plain colonial diet. Many New Zealanders are surprised to learn that fisheries biologists recognise more than 40 native freshwater fish species. If asked about freshwater fish, most people will mention trout (which are not native), eels, and perhaps whitebait. There is little awareness of the variety of native fish in rivers and lakes."[5]

Ousted by trout[edit]

"New Zealanders are more familiar with trout and salmon than with native fish. Trout and salmon were introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Massive trout populations rapidly developed, with adverse effects on native fish through predation, competition for food and displacement from favoured habitats."[5]

Secretive and nocturnal[edit]

"For some reason that scientists do not understand, nearly all native freshwater fish are very furtive creatures. By day they typically live among boulders and pebbles of streams and lake beds, or hide beneath overhanging stream banks, or among logs and woody debris. Most species are also quite small. New Zealand’s eels are nocturnal, as are many other native freshwater fish. An effective, low-tech way of identifying fish, especially in small streams, is spotlighting – shining a broad-beamed torch into a stream at night to see what is out and about."[5]

Small streams[edit]

"The greatest diversity of native fish occurs in small streams – many of them no more than a metre wide. It is not clear why they prefer this habitat. It could be partly because introduced trout have forced them into smaller headwater streams, preying on them or displacing them from their habitats. It is likely that there are other reasons as well."[5]

Protection[edit]

"Freshwater fish are not protected under the Wildlife Act 1953, although native fish are protected in national parks or other conservation lands. For many species, legal protection from being caught is not really an issue as land use and developments that damage their habitats pose far greater threats to their survival. There are some regulations to manage the harvest of eels, whitebait, smelt and lamprey that form small fisheries."[5]

Evolution and characteristics[edit]

Geography[edit]

"New Zealand’s freshwater fish have strong connections with fish of other southern lands. The shortfin eel, īnanga and kōaro are found in eastern Australia, and īnanga in Patagonian South America and the Falkland Islands. In the past some researchers suggested that this spread was because New Zealand, like Australia, was once part of the supercontinent Gondwana. Recent DNA research indicates that it is far more likely that these fish are more recent arrivals, carried around the southern hemisphere on oceanic currents. Some endemic groups such as the pencil galaxias may have an ancient Gondwana heritage."[6]

Evolving from marine species[edit]

"Some species that evolved as marine fish have established themselves in fresh water. Just how this happens is unknown, but at some stage an event must have caused a shift into fresh water. Perhaps a lack of fish diversity in river rapids provided an opportunity for a marine species to invade this environment. The torrentfish still retains its marine connections by living at sea during larval and early juvenile life. The black flounder must still return to sea for spawning and early juvenile life. Several flounder (mainly marine) can also live in river estuaries and lowland lakes. But the black flounder has taken the process a little further – it may be found many kilometres up some rivers."[6]

Links to the sea[edit]

"Nearly half the native freshwater species are found in the sea at some life stage. This may be as larvae and juveniles (as with whitebait species and several bullies), after which they return to fresh water. Some adults (such as eels) may migrate to sea to spawn. In another example, the smelts living in rivers spend most of their lives at sea before returning to fresh water as adults, to spawn. Fish migrate between rivers and the sea at most times of the year, but especially in spring and autumn. These species are known as diadromous (from Greek words meaning ‘running across’)."[6]

Climbing[edit]

"The distribution of the migratory species depends on how far upstream they can move. Rapids and waterfalls are not necessarily barriers. Some species have extraordinary climbing abilities, and can be found upstream of waterfalls tens of metres high. Eels are able to climb like this, and some of the whitebait species, especially kōaro, banded kōkopu and shortjaw kōkopu. These fish climb mostly when small, moving up the wet margins of falls, and using their fins to hold onto rocks by surface adhesion. Some are well known for climbing out of buckets, and if in captivity, often climb out of aquariums (they can climb glass as long as it is damp)."[6]

Stuck in the Nevis[edit]

"For the past half million years Otago’s Nevis River has flowed north into the Kawarau River, which then flows into the Clutha River. But it is thought that the Nevis once flowed south, into Southland’s Mataura River. Supporting evidence is that the Nevis has a Galaxiid species (Galaxias gollumoides) that is otherwise found only in the Mataura and other Southland waterways. The fish is found only in one other isolated locality in the Clutha catchment."[6]

Flexible behaviour[edit]

"Many species can vary their behaviour. Although the ancestral pattern is for them to go to sea, they can establish landlocked populations in the open water of lakes rather than the sea – mostly at the juvenile stage."[6]

Nocturnal activity[edit]

"A high number of native species are nocturnal, moving from under cover to be active at night. Why they are so nocturnal is not understood. The most likely explanation is that it might minimise predation by aquatic birds, especially shags, and perhaps herons. But if it is an avoidance strategy then a paradox emerges. Some fish are habitual prey for large eels, which are also more active at night, emerging from cover to feed."[6]

Galaxiids[edit]

"Most native freshwater fish species are called galaxiids (from the family name Galaxiidae). There are seven genera in the family and two (Galaxias and Neochanna) occur in New Zealand. The name refers to their profusion of small, silvery-gold spots, which were compared to the stars in a galaxy by those who first identified them... In New Zealand there are at least 25 species in this family. New species are still being discovered, with eight recognised since the early 1990s. Galaxiids are a fascinatingly diverse group. Most are shy creatures that few people ever see. A small number of enthusiasts find them appealing and keep them in captivity... Galaxiids have no scales, and their dorsal fin lies toward the rear of the body. The main fins form a propulsion unit towards the tail, making them adept at rapid acceleration and short bursts of speed, though not so well designed for long-distance swimming."[8]

"The galaxioid fishes are the dominant, most speciose group of freshwater fishes (with >50 species) in the lands of the cool southern hemisphere, with representatives in western and eastern Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia, Lord Howe Island, New Zealand, the Chatham, Auckland and Campbell Islands, Patagonian South America (Chile, Argentina), the Falkland Islands and South Africa. The group is most diverse in Australia and New Zealand. Lepidogalaxiidae is found only in Australia, Retropinnidae in Australia and New Zealand, and Galaxiidae across the entire range of the group. Many species are in serious conservation crisis for a diversity of reasons, including habitat deterioration and possibly fisheries exploitation, but there is enduring and pervasive information that shows that the group has been seriously impacted by the acclimatisation of salmonid fishes originating in the cool-temperate northern hemisphere, particularly brown and rainbow trout. With few exceptions, where these trout have been introduced there has been major decline in the galaxioids, especially Galaxiidae, as a result of a complexly interacting series of adverse impacts from these introduced fishes. In some places, centrarchids and cichlids may also have adverse impacts. In addition, there appear to have been adverse impacts from the translocation of galaxioids into communities where they do not naturally occur. In many instances it appears that displacement of the galaxioids has led to a situation where galaxioids and salmonids no longer co-occur, owing either to displacement or predation, leading to fish communities in which there is no explicit evidence for displacement. These effects are resulting in the galaxioid fishes being amongst the most seriously threatened fishes known."[9]

Kōaro relatives[edit]

- taxonomically uncertain

"There is a group of species that are closely related to the kōaro. Scientists are beginning to discover these highly secretive fish in the headwaters of streams in the eastern and southern South Island. Although very similar to the kōaro, they do not have larvae that go to sea. They spawn in spring. Over spring and summer small shoals of whitebait-like juveniles appear in pools and backwaters. They live in open water for several months and grow to about 4 centimetres long, when they disappear into gravels of stream beds and are rarely seen."[10]

Mudfish (Neochanna)[edit]

"Also belonging to the galaxiid family are the Neochanna mudfishes. These are specialised for living in wetlands and swampy spring heads. Best described as cigar-shaped, some may be up to 15 centimetres long. Of five species, three have completely lost their pelvic fins (fins under the body about halfway back to the tail), and in the others these are much reduced. Using their dorsal and anal fins, and well-adapted broad, rounded tails, they swim among the debris of bush wetlands. They are known for their ability to aestivate – spend summer in a state of semi-torpor, surviving if water disappears. Mudfish can survive a long drought. When their wetlands dry out in summer, they find cavities and objects to lie under, breathing air through their skin. As the autumn rains fill the wetlands, the fish are washed out again."[10]

Smelt[edit]

"New Zealand has two fish of the Retropinnidae family. These are the common smelt (Retropinna retropinna) and Stokell’s smelt (Stokellia anisodon). Although smelt have a very strong cucumber odour when they are first captured, the name smelt has nothing to do with this. It is an ancient word for silvery – referring to their colour. Growing to around 10 centimetres, smelt move into lowland rivers from the sea as mature adults to spawn – often being caught towards the end of the whitebait fishing season, in spring. They are very fragile, dying within a minute or two if handled. The smelt populations in some inland lakes, especially in the central North Island, belong to the same species, but have abandoned migrations to and from the sea, spending their whole lives in fresh water."[11]

Links[edit]

- Freshwater fish Department of Conservation,Wellington.

- NIWA Atlas of NZ Freshwater Fishes NIWA.

Conservation status[edit]

Resident native species (40)[edit]

| Conservation status of New Zealand native freshwater fish species (sortable) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Image | Scientific name | Common name | Fish- base |

IUCN status | NZTCS status[12] | Notes | ||

| Anguillidae (eels) |

|

Anguilla australis | Shortfin eel | Not assessed

|

1. Not Threatened

|

"The shortfin eel is quite widely distributed in the South Pacific, and occurs in Australia, New Caledonia, Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, Fiji and possibly Tahiti. Its dorsal fin starts close to the anal fin, and the pectoral fin has 14–16 rays. This eel is olive green and frequents lowland waterways. It can grow to 1 metre and 3.5 kilograms. Males mature, breed and die at 14 years, and females at 22."[14]

"Shortfin eels are one of the three Anguillidae species found in New Zealand. They differ from longfin eels in the length of their dorsal fin. In shortfin eels, the dorsal and anal fins are the same length so the ends are almost adjacent when the fish is viewed side-on. In longfin eels the dorsal fin is longer and extends well forward towards the head. Shortfin eels usually have a silvery belly compared to a yellowish one on longfins, but colours can vary considerably. Even pure yellow shortfin eels have been caught! Shortfin eels are found throughout New Zealand and on Chatham and Stewart Island. However, they are not unique to this country and also occur throughout the South Pacific – in Australia, New Caledonia, Norfolk and Lord Howe Island, and perhaps Fiji. Generally shortfin eels are found at lower elevations and not as far inland as longfin eels, but they are still able to climb large obstacles such as waterfalls when they are young. They are often very numerous in lowland lakes, wetlands, and streams, and shortfin eels form the basis of the commercial eel fishery that has existed for over 20 years in New Zealand. Shortfin eels are our most tolerant native fish species. They survive environmental hazards like high water temperatures or low dissolved oxygen concentrations. That means they can live in habitats where other species cannot survive. Their ability to live almost anywhere might explain why eels are so familiar to New Zealanders and why they were such an important food resource for Maori."[15] | |||

|

Anguilla dieffenbachii | Longfin eel | Not assessed

|

2. At Risk

Declining |

"The longfin eel is found only in New Zealand. Travelling far inland, it may be the country’s most widely distributed freshwater fish. The pectoral (side) fins have 16–20 bony rays. This species is usually dark brown to grey-black on the back. One study found that males swim out to sea to breed and die at an average age of 23 years and females at an average age of 34. They are probably the world’s biggest eels. They may grow up to 1.75 metres, and the biggest caught and measured so far weighed 24 kilograms. Any New Zealand eel over 1 metre long and caught inland is probably a longfin specimen."[14]

"Scientist Don Jellyman figured out the great age of some longfin eels in Lake Rotoiti – the oldest eels yet documented. He found that one female eel was 106 years old by reading the growth rings on its ear bones (otoliths). An average generation time of 93 years suggests that conservative harvest levels must be set in managing these fish. A New Zealand research team at the Mahurangi Technical Institute in Warkworth has hatched baby eels from eggs of the shortfin eel – the first time that commercial quantities of freshwater eel have been bred in captivity. The commercial and ecological implications of this breakthrough could be considerable. Tame eels have become a tourist attraction in places such as Tasman in Nelson and the Anatoki River in Golden Bay."[17] "Longfin eels are distinguished from shortfin eels by the length of the dorsal fin; when viewed side-on, the dorsal fin is longer than the anal fin and extends well forward past the end of the anal fin. In shortfin eels, the dorsal and anal fin ends are almost the same length. Australian longfin eels can be distinguished from native longfins by the presence of irregular black blotches on the back and sides. Longfin eels are only found in New Zealand and occur throughout the country. The elvers are legendary climbers and penetrate well inland in most river systems, even those with natural barriers such as steep falls. Large hydroelectric dams can also be surmounted if appropriate facilities are provided for eel passage, or if elvers are caught at the base of the dam and stocked into the waters above it. Adults can move overland from one waterbody to another (e.g. from a river to an isolated farm pond) by crossing flat grassy land, especially when it is wet. The longfin eel occupies a wide range of habitats and occurs in rivers, streams, lakes ponds and wetlands. Longfin eels are carnivores and over about 40 cm in length they feed mostly on small fish and crustacea. They are responsible for major commercial and customary fisheries in New Zealand. Although the longfin eel is endemic and is one of our most common and largest freshwater fish, there is mounting concern at the scarcity of very large specimens which are being rapidly fished out, and longfin elvers are now becoming scarce as well. Pictures of huge eels used to appear regularly in local newspapers, but not any longer. Commercial harvesting is probably mostly to blame for the scarcity of large eels. These are generally females that contain huge numbers of eggs, and are thus important in sustaining the population. So, if you catch a big longfin – put it back in the water instead of feeding it to the cat!"[18] | ||||

| Eleotridae (bullies) |

"After galaxiids, bullies form the second largest native fish family, known as Eleotridae. They are often called cockabullies, but these are a different family of mostly marine fish. Seven species are widespread across the country. Small fish seen around a lake shore will probably be bullies, most likely the species known as common bullies. Bullies are mostly small, with adults commonly around 10 centimetres long. They have scales and two dorsal fins. The redfin bully male has vivid red coloration, especially on the tail and dorsal and anal fins. These fish are found almost everywhere, although mostly at low elevations. This is partly because the young of four of the seven species spend their first few months at sea: the adults can be found only in places that are accessible from the sea. They have interesting breeding habits. The male establishes his territory, usually in a cavity beneath a large rock, and while guarding it, tends to turn a darker colour. The spawning female is lured into the territory and deposits the eggs, one by one, forming a single layer on the underside of a rock. The male, following along, fertilises them. He then guards them until they hatch.c[11]

"Members of the bully family occupy marine and fresh waters in the tropical Pacific and southeast Asia. There is just one freshwater genera in New Zealand, Gobiomorphus, with seven species...Bullies have rounded tails, two dorsal fins, a blunt head, and are quite stocky. They can sometimes be recognized by their habit of sitting on the substrate looking almost as if they were standing up on their forward fins. They have a darting method of swimming and usually remain on or close to the substrate. Amateurs will have difficulty distinguishing the bully species except for the bluegill and redfin bully, which have some obvious unique characteristics. Fish biologists have to rely on fin ray counts and scale patterns to correctly identify the species, and this usually requires examination of specimens under a microscope. Identification is complicated by the overlapping distribution of many of the species. Of the seven species of Gobiomorphus found in New Zealand, three are strictly diadromous (bluegill, redfin, and giant bullies), while three are non-diadromous (Crans, upland, and Tarndale bullies). The common bully can be either"[19] | ||||||||

| Gobiomorphus alpinus | Tarndale bully | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"Although the Tarndale bully is hard to visually distinguish from the other bully species, its location is a dead giveaway. Found in only a few small sub-alpine tarns in the headwaters of the Clarence and Wairau Rivers, it lives in splendid isolation in this remote region of Marlborough. The bully’s name comes from its location - that part of Molesworth Station formerly known as Tarndale Station."[22] | ||||||

| Gobiomorphus basalis | Cran's bully | 1. Not Threatened

|

"Crans bully is another non-diadromous member of the Eleotridae family. They are stocky little fish that are hard to distinguish from common and upland bullies, whose distributions overlap that of Crans bully. On mature males, the top edge of the first dorsal fin is a bright pinkish-orange, but this is not a useful identification characteristic for small bullies and females. Crans bully is strictly a North Island fish and is found in most areas. Its rarity in the arc northeast of Lake Taupo is thought to be a long-lasting effect of the Taupo eruption over 1800 years ago. As Crans bully has no marine phase, their ability to colonize new river systems is limited, and once they are gone from an area it is unlikely they will re-colonize on their own. With no requirement to go to the sea, Crans bully is most common at sites at mid altitudes and some distance inland. It dwells in stony rivers and streams and does not establish lake populations. Breeding behaviour is similar to the other bullies, with the male establishing a territory, and remaining to guard the eggs after they are laid."[25] | ||||||

| Gobiomorphus breviceps | Upland bully | 1. Not Threatened

|

"The upland bully is one of the non-diadromous members of the Eleotridae family. That means they live their whole lives in fresh water. Adult male upland bullies are relatively easy to identify - they have orange spots on their cheeks and head, and the outer edge of the dorsal fin is also orange. Immature fish and females are less easy to identify, particularly where their distribution overlaps with Crans bully in the lower North Island. Experts have to rely on pectoral fin ray counts under a microscope to ensure that upland bullies can be distinguishd from Crans bullies. Upland bullies are common along the east coast of the South Island. On the west coast, they occur in the Hokitika, Grey, and Buller River systems, but are absent from rivers north and south of there. It was recorded for the first time on Stewart Island in 1998. In the North Island, upland bullies are found from the Ruamahanga River catchment up to the Wanganui and Patea systems. They do not occur in the northern half of the North Island. Because upland bullies do not have to go to sea as part of their life cycle, they occur well inland in many river systems. But they are also found close to the coast. They will tolerate a variety of habitats, from stony-bedded rivers to weedy streams, and have even established populations in a few South Island lakes, e.g. Lake Coleridge. Like all the bully species, the males establish and defend territories during the breeding season. This accounts for their more dramatic colouration compared to the females. The eggs are laid in a primitive nest, which is usually the underside of a large rock. However, instream debris such as wood can also be used. After the eggs are laid, the male guards the nest from intruders and fans the eggs to keep them oxygenated. There is no parental care after hatching."[28] | ||||||

|

Gobiomorphus cotidianus | Common bully | 1. Not Threatened

|

"There are three other bully species that are easily confused with common bullies, and identification is difficult without a microscope. Sometimes faint vertical lines along the cheek are a good characteristic, but this is not always reliable. The location of head pores and the scale pattern on the head are used to distinguish common bullies from Crans and upland bullies, whereas the number of spines in the first dorsal fin distinguishes common from giant bullies. Both of these characteristics are difficult to see in the field. The situation is further complicated by the wide overlap in the distribution of bully species. Common bullies are everywhere in New Zealand. Sea-going populations occur in river and streams near the coast, and land-locked populations have become established in many of our lakes where they are an important prey species for trout and eels. In rivers, they mainly inhabit still or slow-flowing waters and thus are probably one of the most likely bullies to be seen. In lakes, the larvae are planktonic and feed on zooplankton. Eggs are laid on the undersides of hard substrates (wood, rock) in both lakes and rivers, and the egg patches are defended by a male. Apart from a few records from Stewart and Great Barrier Island, common bullies are largely confined to the mainland in New Zealand. Like all the bully species, common bullies are unique to New Zealand. Common bully can grow to a large size; specimens over 120 mm are not unusual."[31] | |||||

|

Gobiomorphus gobioides | Giant bully | 1. Not Threatened

|

"As its name implies, the giant bully is the largest member of the Eleotridae family in New Zealand. Specimens of over 250 mm in length have been reported, although fish in the 120-150 mm range are more common. It is virtually impossible to distinguish the giant bully from the common bully unless you count the number of spines in the first dorsal fin. In giant bullies there are always six spines and in common bully there are usually seven. However, these are difficult to count in the field unless you have some forceps because the spines tend to collapse when the fish is out of the water. Size alone is not a good indicator because common bullies can also grow to 150 mm. The life cycle of giant bullies is somewhat of a mystery. The larvae are thought to have a marine phase, but no juvenile giant bullies have ever been positively identified. In fact, few giant bullies of less than 80 mm have been recorded. Whether small giant bullies have not been distinguished from common bullies or whether they live elsewhere is not known. The adults are never found more then a few kilometres inland and it is possible that they may spend a long period in estuaries before moving into fresh water. Giant bullies have been found in most regions in New Zealand. The slow flowing coastal habitats they live in are difficult to sample although bullies will readily enter fyke nets and traps. To date there have been no studies of this fish so there is no knowledge of its ecological requirements and role"[34] | |||||

| Gobiomorphus hubbsi | Bluegill bully | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"The bright blue gill cover just behind the head readily distinguishes the aptly named bluegill bully from other members of the Eleotridiae family. Small dark spots that cover their cheeks are another useful characteristic. When viewed from the top bluegill bullies are arrow shaped, with their narrow elongate body trailing behind the larger head. Bluegill bullies inhabit similar habitat to torrentfish - swift broken water in open rivers and streams. They also have a similar distribution pattern to torrentfish, being absent from Fiordland, Stewart and Chatham Island, and rare in Otago and Southland. Overall, they are not as common as torrentfish, particularly in Taranaki and Coromandel. Bluegill bullies are the smallest members of the Eleotridiae family in New Zealand. The largest specimen recorded is a 100 mm bully, but most adults are between 60–70 mm in length. In common with all the bully species, bluegill bullies are benthic. Bluegill bullies are strictly carnivorous, and their food is mainly mayfly larvae. Males grow larger than the females and the larger fish (both sexes) are found further upstream than the smaller ones."[37] | ||||||

|

Gobiomorphus huttoni | Redfin bully | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"The bright red fins of an adult male redfin have to make this one of New Zealand's most attractive freshwater fish. Although only males get this distinct colouration, the diagonal stripes on the cheeks make the redfin bully easy to identify. These stripes are even visible in small bullies from about 30 mm in length. Redfin bullies are strictly diadromous and do not establish land-locked populations. Thus, they tend to live near the coast even though they are very good climbers (populations above 5-m-high waterfalls have been recorded). Spawning takes place in fresh water and after hatching the larvae are swept out to sea. The juveniles enter fresh water in the spring and reach maturity about two years later. This diadromous habit means that they are widespread throughout the country and have been frequently recorded from Chatham and Stewart Islands. However, they are rare along the east coast of the South Island above Oamaru, except for Banks Peninsula. Redfin bullies occur mainly in the runs and pools of small bouldery streams and their principal food is mayfly, caddis fly and chironomid larvae. Becuase of their dependance on this habitat, they are more sensitive to the effects of siltation in streams than other fish species. The redfin bully was recognized as a distinct species as early as 1894, but it has had many name changes over the years. The present specific name huttoni honours one of New Zealand's early biologists, Sir Frederick W. Hutton, who was a director of the Canterbury Museum from 1892 to 1905."[40] | |||||

| Galaxiidae | Galaxias anomalus | Roundhead galaxias | 4. Threatened

Nationally Endangered |

"The roundhead galaxias is another non-diadromous member of the Galaxiidae family that is found only in Otago. It occurs in the Taieri and Clutha catchments, although there is still some uncertainty about the records in the Pomahaka. The map shows our best knowledge of its distribution to date and the description below refers to the Taieri roundhead galaxias. The number of caudal fin rays can be used to distinguish the roundhead galaxias (16 fin rays) from the dusky (14 fin rays) and Eldons galaxias (15 fin rays), both of which also occur in the Taieri River catchment. The roundhead galaxias, flathead galaxias and koaro all have 16 caudal fin rays, and distinguishing characteristics for these species rely on the teeth, colour pattern, and shape of the head. Although roundheads are only known to co-exist with flathead galaxias in a single stream, and roundheads have never been found with koaro, positive identification is probably best left to the experts. Roundhead galaxias grow to a maximum size of about 130 mm, but are rarely found larger than 90 mm long. They occupy a diverse range of low gradient streams, from small weedy drains to braided cobble streams. The roundhead is tolerant of high water temperatures and low flows, surviving droughts by living in remnant pools that remain in ephemeral streams. They spawn in early spring, laying their eggs amongst loose gravel and cobbles in riffles and at the stream edge. Spawning sites are used by many fish, and up to 40 individuals can be found at once in areas smaller than 10 x 10 cm".[43] | |||||

|

Galaxias argenteus | Giant kokopu | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"The giant kōkopu (G. argenteus) is a large bulky fish that may grow to more than half a metre long and weigh nearly 3 kilograms – though it is very rarely that big. Notable for their silvery-gold markings, these fish prefer slow-moving waters and lakes, and do not move far inland from the coast. In its juvenile form it is caught as whitebait, along with juveniles of four other native species. When it was first discovered that the adults belong to the same species as whitebait, there was widespread disbelief. It is possible that the common name cockabully originated as a European adaptation of ‘kōkopu’ or a variant such as kōkopuru."[10]

"As its name implies, the giant kokopu is the largest member of the Galaxiidae family. Specimens of over 450 mm in length have been reported, although fish in the 200–300 mm range are far more common. The profusion of golden spots and other shapes on the bodies of larger fish are very distinctive, although small specimens may be difficult to distinguish from banded kokopu. The giant kokopu was the first Galaxiidae to be discovered, and it was its colour pattern that led to the generic name Galaxias, referring to the profusion of stars in the galaxy. Many people are surprised to learn that giant kokopu are one of the whitebait species. However, giant kokopu are uncommon in the whitebait catch and usually run late in the season. Little is known of their spawning habits. It is thought that the adults migrate to a common spawning site, but spawning has never been observed or any eggs discovered. Giant kokopu are primarily a coastal species and do not usually penetrate inland very far. They are endemic to New Zealand but are found on the major offshore islands. Like banded kokopu and koaro, they can establish land-locked populations. In streams, they prefer the slow flowing waters that occur in lowland runs and pools. They are also usually associated with some form of instream cover like overhanging vegetation, undercut banks, logs, or debris clusters. It is thought that they lurk quietly in this cover awaiting their prey, which ranges from koura to terrestrial insects such as spiders and cicadas."[46] | |||||

|

Galaxias brevipinnis | Climbing galaxias | 2. At Risk

Declining |

Whitebait species "Another Galaxias species, kōaro (G. brevipinnis), is found in swift-flowing mountain streams. Many people know it as ‘mountain trout’, but it is not a trout. The kōaro is a handsome fish, dark olive with paler markings, and if you see one out in open water on a fine day, the sunlight glistens along its sides. Some anglers know it as lake whitebait, although the species in lakes do not go to sea like those in rivers. It can grow up to 27 centimetres long."[10]

"The koaro is unlikely to be confused with the other diadromous whitebait species because of its shape. It is more elongate and slender shaped, almost like a tube. The sides and back are covered in a variable pattern of light patches and bands that making the koaro a very attractive fish. Unfortunately, it is not so easy to tell the koaro apart from some of the non-diadromous galaxiids like the Canterbury galaxias and those that live in Southland and Otago. Identification problems are complicated by the fact that koaro can co-habit with the other species in the same rivers and streams. Even the experts have problems separating them, relying on technical measures such as the number of caudal fin rays to ensure correct identification. Koaro have the ability to penetrate well inland in many river systems, and thus have a more widespread distribution than the other whitebait species. In addition to the mainland, they are also found on Chatham and Stewart Island, in Australia, and on the sub-Antarctic Auckland and Campbell Island. Rocky, tumbling streams are the preferred habitat of koaro, and they are almost always found in streams with native bush catchments except for tributaries of upland lakes that may be above the bush-line. Studies in Australia found that koaro spawned in damp areas along the edges of the streams they lived in, relying on subsequent floods to inundate the eggs for hatching. A requirement for dampness could explain their preference for forested streams, and shows why their distribution in New Zealand has probably been curtailed by widespread forest clearance, more so than most of the other Galaxiidae. Although koaro comprise part of the whitebait catch, they also form land-locked populations in lakes. For example, koaro populations occur in the catchments of many of the Rotorua lakes, Taupo, Rotoaira, Manapouri, Tekapo, Pukaki and Wanaka. Koaro populations in lakes were decimated by predation from introduced trout and are now much lower than in pre-European times when they provided a fishery for Maori. In lakes, where smelt have been introduced, koaro have declined even further and are either now confined to tributary streams or have become extinct."[49] | |||||

| Galaxias cobitinis | Lowland longjaw galaxias | 5. Threatened

Nationally Critical |

"The little-known group of small, thin galaxiids known as pencil galaxias live most of their lives in the gravels of stream beds. Most distinctive are the longjaw galaxias – two similar and closely related species with a protruding lower jaw. These little fish (up to 7.5 centimetres long) are superbly adapted for picking small aquatic insects from under stones in pools and shallows. Researchers are only now learning about their habits. It is possible that some of these fish may actually live deep in river gravels."[10]

"The lowland longjaw galaxias was first described from specimens caught in the Kauru River, a tributary of the Kakanui River in north Otago. Previously, these longjaw populations were thought to be disjunctive, lowland populations of Galaxias prognathus, the upland longjaw. However, DNA sequencing showed that the Kauru River fish were highly divergent from the other longjaws, and that it is a distinct species. Although its distinctly protruding lower jaw distinguishes this galaxiid from most of the others, it also has only 5 pelvic fin rays, compared to 7 for the other galaxiids, and fewer caudal rays and vertebrae compared to upland longjaws. Based on its location, the new longjaw species was given the common name of lowland longjaw galaxias. This was unfortunate because recent surveys have shown that this fish also occurs in parts of the upper Waitaki catchment and so is not a lowland species. A single specimen from the Hakataramea River in 1989 was positively identified as a lowland longjaw, but no other longjaws have been found there since. How this species came to be present in such widely separated locations is a mystery, although further surveys may show that it is even more widespread. Generally, the lowland longjaw looks similar to its upland cousin; it is a slender elongate fish lacking strong colouration. It is also quite small, rarely exceeding 70 mm in length. Adult fish occur in the margins of riffles and runs, but in daylight are usually hidden under rocks and stones. Spawning occurs in late winter and spring, and juvenile longjaws, which lack the distinctly protruding jaw that adults develop, are readily visible in backwaters and side braids from October to January."[52] | ||||||

| Galaxias depressiceps | Flathead galaxias | 3. Threatened

Nationally Vulnerable |

"The flathead galaxias is another of the recently discovered non-diadromous Galaxiidae that are only found in Otago, primarily in the Taieri River catchment. It was formally described as a new species in 1996, and its scientific name refers to its distinctly flattened (depressus) head (ceps). Other non-diadromous galaxids with flat heads have been found in the Clutha catchment and in Southland, but recent comparisons by Otago University suggest these are distinct from G. depressiceps with 3 new species awaiting formal recognition. Clearly, sorting out the taxonomy of the Otago/Southland galaxiid complex is going to take more time. At present, this species of flathead galaxias is known mainly from streams in the Taieri catchment, but also the Shag, Waikouaiti and some coastal streams south of the Taieri. The flathead galaxias is difficult to distinguish from some of the other galaxiids that appear to be restricted to the Taieri catchment, although the number of caudal fin rays can be used to distinguish flathead galaxias (16 fin rays) from the dusky (14 fin rays) and Eldons galaxias (15 fin rays). Telling flathead galaxias apart from roundhead galaxias and koaro, also with 16 caudal fin rays, is more difficult, relying on the teeth, colour pattern, and the flattened head. Flathead galaxias often also have a golden stripe down the centre of the back to the dorsal fin and a golden belly. These three species never occupy the same stream, but koaro and flatheads or roundheads and flatheads do co-exist, albeit at few sites. The distribution of the flathead galaxias is fragmented, possibly a consequence of impacts from the introduced brown trout. The preferred habitat for this species is cobble/boulder streams in tussock grasslands, and most populations occur above large waterfalls. Flatheads are found at altitudes of 140-1130 m in Otago, and they can live in steep mountain streams. Flatheads reach a maximum size of 168 mm, but are usually less than 125 mm."[55] | ||||||

| Galaxias divergens | Dwarf galaxias | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"The scientific name for this species indicates that it diverges from the other members of the Galaxiidae family: it has only 6 pelvic fin rays compared to the more usual 7 for the other galaxiids. The number of caudal fin rays (15) is also different from most other galaxiids, except for Eldons galaxias. However, dwarf and Eldons galaxias do not co-exist, with Eldons galaxias being confined to Otago. The dwarf galaxias is amber to olive green in colour with dark brown blotches on the sides and back. The belly is silvery. The whole life cycle of the dwarf galaxias occurs in fresh water, and the maximum size of these fish is about 90 mm, although most adults are usually less than 70 mm in length. Aquatic larvae of mayflies and midges are the most commonly eaten foods of the dwarf galaxias. Of the non-diadromous members of the Galaxiidae family, the dwarf galaxias has the widest distribution, although this pattern is extremely fragmented. In the North Island, dwarf galaxias occur in the headwaters of the Waihou River near Putaruru, at a few sites in the Rangitaiki River near Galatea, in Hawkes Bay, and the Wellington region. In the South Island, it occurs in Marlborough and Nelson, and on the west coast as far south as the Hokitika River. Recent studies show there are some genetic differences between the populations, but probably not enough to warrant any separate species"[58] | ||||||

| Galaxias eldoni | Eldon's galaxias | 4. Threatened

Nationally Endangered |

"This member of the non-diadromous galaxiid group has a very restricted distribution; it is confined mainly to tributaries in the lower to mid Taieri River catchment. This is another new Otago galaxiid species and it was first formally described in 1997. The name honours G.A. Eldon, who assisted Dr R.M. McDowall with his investigations into the galxiidae. Eldons galaxias closely resembles the flathead galaxias, but it has a deeper body and darker colouration, especially in large individuals. Its can also be distinguished from the flathead and other galaxiids by the number of caudal rays (15 in Eldons, 16 in the flathead, and 14 in the dusky galaxias). It shares this characteristic of 15 caudal rays with the dwarf galaxias, but their distributions do not overlap. Although the full extent of their occurrence is not yet known, it appears that the distribution of Eldons galaxias is highly fragmented. This may be caused by competition from the introduced salmonids: brown trout, rainbow trout and brook char. The establishment of land-locked populations of native koaro in Lake Mahinerangi may have also affected their distribution. Eldons galaxias reaches a maximum size of about 150 mm and are commonly found up to 110 mm long. Like most of the non-diadromous galaxiids, Eldons galaxias feeds on aquatic insects, occasional terrestrial items, and on rare occasions, small koura. They can often be seen during the day feeding on items drifting downstream. Eldons galaxias tends to prefer riffle habitats, but can also be found in pools. They occupy a diverse range of streams from high altitude tussock streams to low altitude forested ones. Often they are found upstream of large waterfalls that restrict the distribution of salmonids. Spawning occurs in mid-spring, and the larvae hatch about a month or so later."[61] | ||||||

|

Galaxias fasciatus | Banded kokopu | 1. Not Threatened

|

Whitebait species "Some other species of Galaxias are fairly well-known. The banded kōkopu (Galaxias fasciatus) is another of the whitebait species, with adults commonly growing to around 20 centimetres. It is known as ‘native trout’ or ‘Māori trout’ – but it is no trout... It is greyish-brown with vertical pale bands across its sides – providing camouflage in the dappled light on small bush streams. Banded kōkopu inhabit pools in the smallest streams, some of which are only half a metre wide with scarcely enough room for the bigger fish to turn round. When people live nearby, the fish can be quite tame, taking food from the surface of pools, and even jumping to take it from your hand."[8]

"This member of the Galaxiidae family is one of the five species that occur in the whitebait runs that enter our rivers each spring. Banded kokopu are generally the smallest of the five species when they are whitebait and have an overall golden colour. The juveniles are very good climbers and will often escape from buckets by clinging to and wriggling up the sides. Adult banded kokopu can be distinguished from the other galaxiid species by the presence of the thin, pale, vertical bands along the sides and over the back of the fish. These bands begin to develop quite early, but similar bands also appear on juvenile giant kokopu, and it is easy to confuse young fish of these species. It is probably best to send small specimens to a fish biologist for identification. Banded kokopu commonly grow to over 200 mm, and fish of this size should be no problem to identify correctly. Adult banded kokopu usually live in the pools of very small tributaries where there is virtually a complete overhead canopy of vegetation. This vegetation does not have to be native bush, however, and banded kokopu happily live in urban streams and streams under exotic pine plantations so long as overhead shade is present. They only occur in pools where there is instream cover such as an undercut bank, large rocks or wood debris. They depend on terrestrial insects for a large proportion of their diet and can detect the small ripples made by moths and flies that become stuck on the water surface of the pool. Although the juveniles are good climbers, banded kokopu do not penetrate very far inland and are primarily a coastal species. They are found on Chatham and Stewart Island, but occur only in New Zealand. Banded kokopu are rare along the east coast of the North Island south of East Cape and down the east coast of the South Island, but common elsewhere. This distribution is probably a result of intensive land development and the sensitivity of the juveniles to suspended sediments. Rivers containing glacial flour or eroding sedimentary catchments are not attractive to the whitebait of this species."[64] | |||||

| Galaxias gollumoides | Gollum galaxias | 3. Threatened

Nationally Vulnerable |

"This recently described member of the Galaxiidae family was only recognized as a distinct species in the last few years. Because this fish was first found in a swamp and has relatively large eyes, its name refers to its similarity to Gollum, a character in J.R.R. Tolkein's “The Hobbit” and “Lord of the Rings”. Recent studies at Otago University indicated that it occurs on Stewart Island, throughout the Catlins and Southland, and in the Nevis River (which used to drain into the Mataura). The best way to tell this species apart from other galaxiids is by counting the pelvic fin rays; the Gollum galaxias has 6 pelvic fin rays whereas most of the other galaxiids usually have 7. The two galaxiids that also have 6 pelvic fin rays, Eldons and dwarf galaxias, do not co-exist with the Gollum galaxias. No detailed studies of its life history have taken place yet, but its life cycle is probably similar to that of the other non-migratory galaxiids, with spawning taking place in spring, and the whole life cycle occurring in fresh water. The largest Stewart Island fish recorded is 75 mm, but Southland populations contain fish up to 150 mm long."[67] | ||||||

| Galaxias gracilis | Dwarf inanga | 2. At Risk

Declining |

"The dwarf inanga looks like a small inanga and is closely related to inanga. However, it is found in only 13 lakes near Dargaville in the North Island. As its name implies, it is the smallest member of the Galaxiidae family in New Zealand. Specimens of over 80 mm in length are rare, and mature adults may be only 40 mm. Juveniles school around the lake edges where rushes and macrophytes provide shelter from predators. They feed on zooplankton in open waters at night. Adults occur in deeper water near the middle of the lake and return to the littoral zone at night to feed on the larger invertebrates present there Dwarf inanga populations have declined over the past 30 years, and it is now considered to be a threatened species. The introduction of rainbow trout into some of the lakes it inhabits (especially the Kai Iwi lakes) was initially blamed for this decline, as trout are known to eat inanga. However, removal of trout from one lake did not increase the abundance of dwarf inanga and, up until 2000, it was abundant in Lake Ototoa which was routinely stocked with trout. Gambusia is now thought to be responsible for its scaricty in Lakes Taharoa nd Waikere, and for its extinction in Lake Kai Iwi."[69] | ||||||

| Galaxias macronasus | Bignose galaxias | 3. Threatened

Nationally Vulnerable |

"The bignose galaxias is yet another non-diadromous galaxiid from the South Island that has only recently been described. It was distinguished as a new species based on DNA sequencing and its morphology. The bignose galaxias is closely related to what are referred to as the “pencil galaxias”, small, slender (pencil-shaped), non-diadromous, mainly sub-alpine galaxiids with small fins and long, slender caudal peduncles (G. divergens, G. paucispondylus, G. prognathus and G. cobitinis). It can be distinguished from these species because it has only 4–6 pelvic fin rays (usually only 5) and only 11–14 caudal rays. It also has a distinctly rounded lateral head profile with the upper margins of the eyes being well below the dorsal profile. Bignose galaxias are found in several locations in the Mackenzie Basin in the upper Waitaki River catchment. Generally it is found in small spring or wetland-fed tributaries. Little is know about its life history, although this is probably similar to the other pencil galaxiids. Sexually mature fish were found in June and July, suggesting spawning takes place in winter."[72] | ||||||

|

Galaxias maculatus | Common galaxias | 2. At Risk

Declining |

Whitebait species "The most widespread and best known of the galaxiids is īnanga (Galaxias maculatus). Unlike most of its relatives, it is the one Galaxias species that lives in the open waters of pools. It swims in smallish, roving shoals, in pools and runs of lowland rivers and in wetlands".[8]